Varieties of Healing 2:

A Taxonomy of Unconventional Healing PracticesThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Annals of Internal Medicine 2001 (Aug 7); 135 (3): 196–204 ~ FULL TEXT

Ted J. Kaptchuk, OMD, and David M. Eisenberg, MD

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center,

Harvard Medical School,

330 Brookline Avenue, W/K-400,

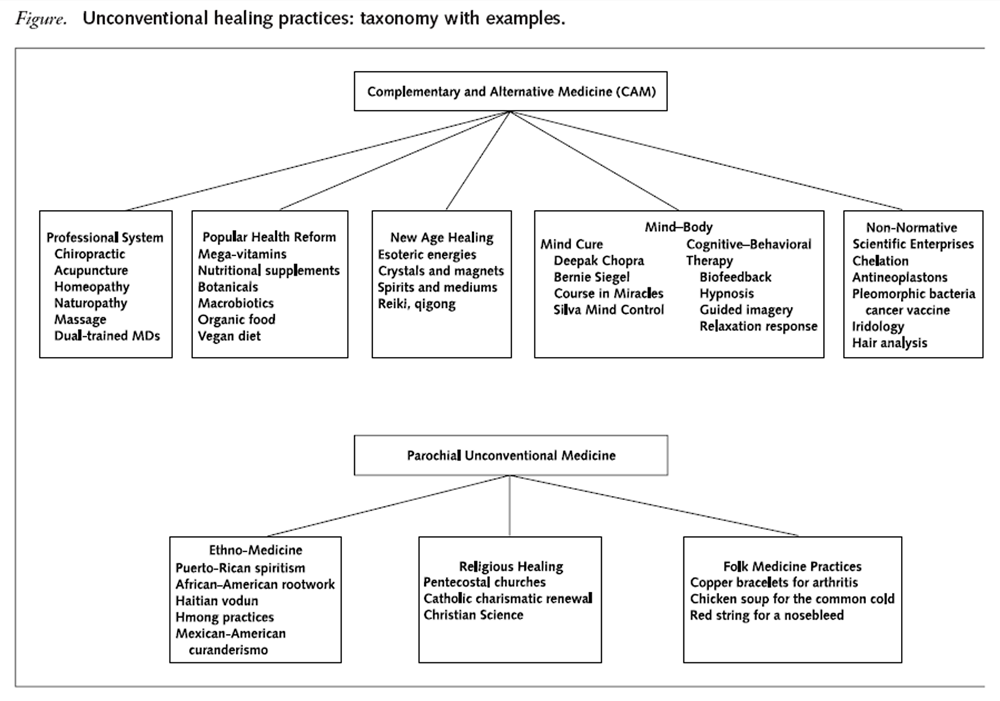

Boston, MA 02215, USAThe first of two essays in this issue demonstrated that the United States has had a rich history of medical pluralism. This essay seeks to present an overview of contemporary unconventional medical practices in the United States. No clear definition of "alternative medicine" is offered because it is a residual category composed of heterogeneous healing methods. A descriptive taxonomy of contemporary unconventional healing could be more helpful. Two broad categories of unconventional medicine are described here: a more prominent, "mainstream" complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and a more culture-bound, "parochial" unconventional medicine. The CAM component can be divided into professional groups, layperson-initiated popular health reform movements, New Age healing, alternative psychological therapies, and non-normative scientific enterprises. The parochial category can be divided into ethno-medicine, religious healing, and folk medicine. A topologic examination of U.S. health care can provide an important conceptual framework through which health care providers can understand the current situation in U.S. medical pluralism.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Defining unconventional medicine by “what it is” does not work. Alternative medicine is an umbrellalike term that “represents a heterogeneous population promoting disparate beliefs and practices that vary considerably from one movement or tradition to another and form no consistent . . . body of knowledge”. [1] Alternative medicine is a large residual category of health care practices generally defined by their exclusion and “alienation from the dominant medical profession”. [2]

Besides an absence of shared principles, an accurate definition of alternative medicine is further confounded because the boundary demarcating conventional and irregular medicine has always been porous and flexible. [3] Therapies move across that border; for example, nitroglycerin [4] and digitalis [5] began as alternative drugs, just as corn flakes and graham crackers began as unconventional health foods. [6] Entire professions change sides. In 1903, when the American Medical Association needed both a larger referral base for specialists and new allies in its fight with osteopaths, chiropractors, and Christian Scientists, it boldly reversed its policy and declared homeopaths to be conventional MDs. [7] Likewise, osteopathy ceased being a renegade profession after World War II. [8–10]

The first of two essays in this issue (pp 189–195) demonstrated that the United States has had a rich history of medical pluralism. This essay offers an overview of alternative medicine. Because of the inherent problems in defining a flexible residual category, we present a taxonomy of what is currently considered unconventional healing in the United States.

Figure The number of named alternative therapies available in the United States easily soars into the hundreds. [11–16] Many classification systems have been proposed. [17–24] In an effort to further discussion, we offer a new taxonomy that we believe configures the domains of unconventional medicine across a broader spectrum of health practices. We do not expect that our attempt will be definitive (nor do we necessarily believe a perfect schema is possible). Any classification system is limited because such human phenomena resist discreteness as well as being fixed in time. As we point out, overlap often occurs. Inevitably, subjectivity affects the categorization and perceptions of “affinities.” A summary of our schema is presented in the Figure.

Unconventional healing practices can be divided into two types: one that appeals to the general public and another that confines itself to specific ethnic or religious groups. The broadest category of unconventional medicine is easily recognized because its health care claims to be independent of any sectarian belief or faith and is said to depend on universal and even “scientific” laws. [25] It is the best-known variety of unconventional medicine in the United States and recently, in a loose alliance, has become known as complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). [25]

The second kind of unconventional practice is typically confined to narrow groups, such as members of particular religions (for example, Pentecostal Christians), ethnic groups (for example, Puerto-Rican spiritism), or regions (for example, southern Appalachian folk beliefs). These practices are culturally self-contained, function outside any broader coalition, often lack the markings of a health delivery system, and in this essay are referred to as parochial unconventional medicine.

COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE

The wide-ranging category of CAM can be divided into five main sectors, which are described below.

Professionalized or Distinct Medical Systems

Probably the most recognizable alternative healing practices are those that are organized into medical movements with distinct theories, practices, and institutions. Licensure as an independent profession is a goal if not always an actuality. Medical institutions, such as schools, professional associations, and offices with secretaries and billing procedures, are readily visible. An extensive corpus of technical literature helps guide therapy and practice and sharpens distinctness. Because they are easiest to describe and define, these systems are the most prominent in discussions of CAM. The six major components of this sector of CAM are chiropractic, acupuncture, homeopathy, naturopathy, massage, and dual-functioning MDs.

Chiropractic, the largest alternative medical profession in the United States, accounts for almost a third of all visits to CAM providers. [26] The body’s biomechanical structure, especially the spine, is seen as basic to health, and chiropractic emphasizes spinal manipulation as treatment. [27, 28] Licensed as primary health care providers in all 50 states, chiropractors especially treat musculoskeletal disorders. [29, 30]

Osteopathy was once a second manual therapy competing for the same patients as chiropractic. Since World War II, osteopathy has reconfigured itself and has become “conventional”; the status of an osteopathic physician is equivalent to that of an MD. A minority of patients (.17%) visiting DOs receives the kind of manipulative therapy that would still be considered unconventional by orthodox MDs. [31, 32]

Acupuncture relies on the insertion of fine needles at well-defined specific sites to regulate and balance humoral forces and “energy” (qi) and to promote health. [33] As a component of East Asian medicine, acupuncture is often complemented with herbal treatment. Since the 1970s, acupuncture has spread throughout the United States and is independently licensed as a health care profession in 37 states. [34]

Homeopathy uses the principle of “like cures like”: A substance that produces a set of symptoms in a healthy person is used to treat an identical symptom complex in a sick person. [35, 36] The substance, however, is extremely diluted, often to the extent that none of the original substance is likely to remain. Currently, homeopaths can be independently licensed in only three states, but other licensed practitioners also prescribe these remedies.

Naturopathy uses a wide assortment of therapies that its practitioners call “natural.” Herbs, nutritional supplements, dietary and lifestyle advice, homeopathy, manipulation, and counseling can all be components of the repertoire. [37] The term naturopathy was adopted in 1902 to replace the old word hydropathy, which denoted water-cure therapy. Currently, naturopaths can be licensed as primary care providers in 11 states; naturopathy is most common in the Pacific Northwest. [38]

Massage therapists can be professionally licensed in more than 25 states. [39] Although massage therapists (also called “body-workers” or “hands-on therapists”) clearly perform unorthodox interventions [40–42], they overlap with recognized biomedical professions, such as physical therapy, or simple attempts at relaxation. Complementary alternative medicine techniques that address body alignment and awareness (such as the Feldenkrais method [43] and the Alexander technique [44]) are often classified as massage therapy because they involve “body-work.”

Medical doctors who have opted to deliver, supervise, or advocate CAM are a significant force in alternative medicine. [15, 46] These dual-trained practitioners lend enormous prestige and legitimacy to alternative medicine and can be prominent spokespersons. [47–50] Providing what is sometimes called “integrative” medicine, these physicians can deliver a broad range of CAM services or can focus on a single therapy.

Popular Health Reform (Alternative Dietary and Lifestyle Practices)

The health food movement, also known as alternative dietary and lifestyle practices, is an important component of CAM. Depending on how one calculates, it may in fact dwarf the professional sector. [51] In the scholarly literature, this type of healing is labeled “popular health reform” because these practices are often advocated by untrained laypersons who often claim knowledge superior to that of expert scientists. [6]

Popular health reform is delivered by a melange of resources, such as health food stores, popular books and journals, charismatic leaders, alternative provider recommendations, mass media attention, and a considerable amount of neighborly advice. This popular movement usually espouses a vegetarian or near-vegetarian diet, or avoidance of chemically treated and, more recently, radiated or genetically altered food. Details of particular programs tend to have enormous heterogeneity. Recommendations might range from eating only cooked food (for example, macrobiotics [52]) to eating only raw food (for example, fruitarianism) [53], or from heavy reliance on nutritional and botanical supplements or aromatherapy to their absolute prohibition. Recent shifts in biomedicine’s understanding of nutrition and its role in pathophysiology have also encouraged a general social movement toward behaviors that were once thought to belong to health food “nuts”. [54] This, in turn, has caused a blurring of the distinction between orthodox and unorthodox lifestyles and has helped increase the awareness of CAM in society. [51]

New Age Healing

The New Age is the source of many extremely disparate beliefs and practices that can describe overlapping religious and healing movements. [55, 56] Furthermore, confounding discussion, the term New Age may not be “adopted by a given individual (indeed, may be rejected), even though to outsiders the practice appears to fall into this category”. [57] As a religious movement, the New Age is about a “new dispensation”: less about law and limitation and more about unrestricted self-expression and unlimited abundance. Instead of any fixed religious doctrine, the movement emphases a fluid “spirituality.” It is not uncommon to see an iconography that is a grab bag of Hindu, Christian, Buddhist, Rosicrucian, and pagan motifs. [18]

The New Age is also a health care category because spiritual equanimity and physical health are considered to be linked. In fact, New Age beliefs resist any separation between spirituality and physical health or faith and medicine. Scholars point out that the New Age seeks a “third way,” “a spiritual science,” between revealed biblical religion and “atheistic–materialist” science. [58]

A key New Age connection between the spiritual and physical realms involves esoteric energies that resemble a veritable “electromagnetic” dimension of wellness. [59, 60] The names of the energies change—life force, universal innate intelligence, psychic, parapsychological, psi, astral, spiritual vital force—but they inevitably elude scientific detection. [61] Healers can transmit these forces. Devices and substances that emit them, such as radionic machines, magnetic devices, pyramids, crystals, and other electromagnetic gadgets, are constantly being incarnated. The health influence of planets and stars and some medical astrology could be considered another type of such energy. [62] Healing energy therapies not explicitly connected to the New Age, such as “therapeutic touch” (often applied by nurses) [63] and “laying-on of hands” [64], can ultimately be traced here. New “energy” forces are being recruited from Asia. Chinese qigong [65] and Japanese Reiki [66], while obviously not originally New Age, find it a hospitable environment for cross-cultural migration. [61]

Sometimes the religious and health domains are bridged through “clairvoyant physicians” or the healing presence of the spirits, religious icons, or leaders. [67–70] Best-selling books by spirit mediums who describe spiritual healing for “incurable diseases and maladies” help keep the phenomena in prominent view. [71] A third type of New Age healing connection between the cosmos and human health operates through “mind” forces and can also be considered a subcategory of CAM psychological intervention (see following discussion).

Psychological Interventions: Mind Cure and “Mind–Body” Medicine

Psychotherapeutics in CAM has two sources: one that is purely CAM and one that overlaps with conventional psychological interventions. In the scholarly literature, the exclusively CAM psychological tradition is referred to as Mind Cure or New Thought. [17, 72–74] These therapies, which can include a myriad assortment of visualizations, affirmations, intentions, meditations, and emotional release techniques, all share a single point: Mental forces are the preeminent arbiters of health. Psychotherapists affiliated with CAM believe that the mind is the most dominant agency for restoring well-being and maintaining health. The notions that “What you think is what is real” and that “Your emotions determine cancer or other major disease” are dogma repeated over and over like mantras. Such bestsellers as Bernie Siegel’s Love, Medicine and Miracles and Deepak Chopra’s Ageless Body, Timeless Mind: The Quantum Alternative to Growing Old testify to the appeal of these beliefs.

The other sector of CAM “mind–body” therapies merges into conventional psychotherapy and cognitive– behavioral interventions. The relationship can be confusing or can produce gray areas. Generally speaking, in conventional medicine, psychotherapeutics is conceded only limited agency and is primarily used to treat psychological problems or to help patients cope when conventional treatments are not available or are insufficient. Psychotherapeutics remains a subordinate component of the conventional medical system. [75, 76]

However, whenever too much power or efficacy is attributed to regular psychological therapies and they are used “off-label,” they “transgress” and can become CAM. For example, most MDs would consider psychotherapy appropriate for reactive depression after a cancer diagnosis, but psychotherapy used to cure a metastatic tumor would be considered unconventional. [77] The same holds true for various cognitive–behavioral therapies that use “passive nonvolitional intention,” such as biofeedback, stress management, relaxation response, meditation, guided imagery, and hypnosis. When practitioners of these techniques make modest claims limited to small physiologic changes, the techniques are acceptable as subordinate components of conventional medicine. For example, biofeedback for fecal incontinence [78] or, more debatably, relaxation response for mild hypertension [79, 80] can seem legitimate or can at least achieve borderline acceptability, but both would be considered distinctly alternative if used to treat diabetes.

Another source of CAM psychotherapeutics involves the fact that between 250 [81] and 400 [82] named types of psychological treatments are thought to exist. Any therapy deemed unacceptable by the mainstream can find a receptive home in CAM. Also, whether self-help groups, such as Alcoholics Anonymous, are CAM is highly debatable, but to the extent that they are not conventional they can automatically be described as alternative. [83, 84]

Non-Normative Scientific Enterprises

Non-normative scientific enterprises typically appeal to patients with potentially catastrophic illnesses, such as cancer. These therapies can include sophisticated pharmacologic agents and often revolve around a wellknown proponent who can have legitimate and even impressive scientific or medical credentials but advocates theories and practices unacceptable to the general scientific community. Examples include Dr. Stanislaw Burzynski’s “antineoplastons” and Dr. Virginia Livingston-Wheeler’s “pleomorphic bacteria cancer vaccine”. [85, 86] Non-normative interventions can sometimes blur into the conventional practice of prescribing recognized pharmaceuticals for off-label uses. [87–89] Unvalidated diagnostic methods and unconventional technological devices that diagnose or heal can be considered part of the non-normative science category. Representative examples are hair analysis, which purportedly detects a wide variety of diseases and nutrient imbalances [90]; iridology, in which illness is diagnosed through a detailed examination of the iris [91]; and chelation therapy to reverse the processes of arteriosclerotic disease. [92]

PAROCHIAL UNCONVENTIONAL MEDICINE

Unlike CAM, parochial unconventional practices appeal to a more narrowly defined constituency. Three main parochial categories exist.

Ethno-Medicine

The healing practices of specific ethnic populations make up a critical component of U.S. community health care. [93] These practices are rooted in the widely differing medical or religious traditions of various cultures. Well-known examples include Puerto-Rican spiritism, [94, 95], Mexican-American curanderismo [96, 97], Haitian vodun [98, 99], Native American traditional medicine [100], Hmong folk practices [101], African-American “rootwork” [102], and African-American spiritual church healing. [103, 104] Occasionally, a culture-bound medical system ventures outside its historical sphere of influence and becomes another option available to the general U.S. population. This is true of acupuncture and seems to be coming true for India’s Ayurvedic medicine as it follows in the footsteps of yoga, its pioneering offspring. [105] Partly because of New Age affinities, this may also happen with Tibetan medicine and Native American ceremonies. [106, 107] Nonetheless, as a general taxonomic statement, consistent with stubborn racist prejudices, one could say that medical practices of ethnic communities are described as ethno-medicine while the “ethno-medicine” of mainstream white Americans is generally classified as CAM.

Folk Medicine Practices

Folk healing practices form a deeply embedded, unorganized, and seemingly spontaneous response to illness. Many of these practices are confined to specific geographic areas, such as southern Appalachia [108] or rural New Hampshire. [109] Sometimes they can be traced back to remnants of ethnic (including Anglo- Saxon) magical traditions or earlier lay forms of self-care and home remedies. Common practices include wearing copper bracelets for arthritis, covering a wart with a penny and then burying the penny, stopping a nosebleed by placing a red string around the neck, and curing a cold with chicken soup. [110–113] Besides cures, folk beliefs can also generate culture-bound diseases, symptoms, and treatment-seeking behaviors. [114, 115] Some folk practices have a more widespread currency and are derived from earlier layers of premodern medicine (for example, humoral Hippocratic medicine) or medieval medical schools (for example, astrological medicine). [116, 117] Examples of remnants of Hippocratic ideas include such folk wisdom as “Bundle up to prevent a cold” or “Feed a cold and starve a fever”. [115, 118, 119]

Religious Healing

Many Americans rely on religion for salutary effects on their health. [120, 121] Generally, normative mainstream religious institutions have seen their role as supporting the “spiritual” dimension and avoid direct overlap or competition with the biomedical system. [122] This division of labor has weakened somewhat lately; “healing” services of one kind or another have appeared even in liberal churches and synagogues. [123, 124]

The most salient forms of religious healing for physical disease can be found in Christian churches that see their ministry as replicating the miraculous healings recorded in the Bible. [125, 126] This is especially true of the Pentecostal and charismatic churches, which seek to encounter and affirm the divine as manifest in both physical and mental healing. [127, 128] People rising from wheelchairs or discarding crutches can be convincing signs of God’s power. [129, 130] Christian Science, whose origins may be closer to Mind Cure than to Christianity, also continues to be an important nonnormative source of healing in the United States. [131, 132] Some religious denominations are also known for nonadherence to normative procedures (for example, Jehovah’s Witnesses, who routinely decline blood transfusions). [133, 134] For any of these religious approaches, genuine “faith” is required in exchange for the promised effectiveness. Also, these approaches sharply distinguish themselves from participation in any professed coalition with the CAM movement. [135]

OVERVIEW

Unconventional healing is a far-flung landscape of diverse practices. A taxonomy balances distinction with commonality. Other perspectives that emphasize interconnection and common themes are possible. Healing behaviors can be grouped into those that focus on the primacy of substances to be taken orally (herbs, homeopathy, dietary supplements, or food), those that rely on the human hand (manipulation, needles, or anointing the sick), or those that emphasize words (ritual or psychotherapy). [23, 136] One could also discuss CAM approaches on the basis of shared common themes (for example, belief in nature, vitalism, and spirituality), as has been done extensively elsewhere. [25] No matter how it is classified, however, this entire domain provides concrete practices and “pathways of words, feelings, values, expectations [and] beliefs” that reorder and organize the illness experience. [137] Because patients include unconventional healing as an important component of their response to illness, physicians must understand this complex spectrum of health care practices.

CONCLUSION

A single definition of alternative medicine that tries to state “what it is” inevitably is not satisfying, since alternative healing includes a wide assortment of heterogeneous therapies and beliefs. A taxonomy of unconventional health care practices can help define alternative medicine and provide a conceptual framework for it. Such a model can help physicians understand and participate in the current discussion on unconventional healing practices as it rapidly unfolds.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank Robb Scholten and Maria Van Rompay for research assistance and June Cobb and Marcia Rich for editorial suggestions.

Grant Support:

In part by educational grants from the National Institutes of Health (U24 AR43441), John E. Fetzer Institute, the Waletzky Charitable Trust, Friends of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and American Specialty Health Plan.

References:

Gevitz N. Alternative medicine and the orthodox canon. Mt Sinai J Med. 1995;62:127-31. [PMID: 0007753079]

Gevitz N. Three perspectives on unorthodox medicine. In: Gevitz N, ed. Other Healers: Unorthodox Medicine in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ Pr; 1988.

Defining and describing complementary and alternative medicine. Panel on Definition and Description, CAM Research Methodology Conference, April 1995. Altern Ther Health Med. 1997;3:49-57. [PMID: 0009061989]

Fye WB. Nitroglycerin: a homeopathic remedy. Circulation. 1986;73:21-9. [PMID: 0002866851]

Eisenberg DM, Kaptchuk TJ. The herbal history of digitalis: lessons for alternative medicine [Letter]. JAMA. 2000;283:884-6. [PMID: 0010685707]

Whorton JC. Crusaders for Fitness: The History of American Health Reformers. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ Pr; 1982.

Rothstein WG. American Physicians in the 19th Century: From Sects to Science. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ Pr; 1972.

Wardwell WI. Differential evolution of the osteopathic and chiropractic professions in the United States. Perspect Biol Med. 1994;37:595-608. [PMID: 0008084743]

Gevitz N. The D.O.’s: Osteopathic Medicine in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ Pr; 1982. [PMID: 0006362988]

Albrecht GL, Levy JA. The professionalization of osteopathy: adaptation in the medical marketplace. In: Roth JA, ed. Research in the Sociology of Health Care. v 2. Greenwich, CT: JAI Pr; 1982.

McGuire MB. Words of power: personal empowerment and healing. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1983;7:221-40. [PMID: 0006362988]

Hafner AW, Zwicky JF, Barret S, Jarvis WT. Reader’s Guide to Alternative Health Methods. Chicago: American Medical Assoc; 1993.

Burroughs H, Kastner M. Alternative Healing: The Complete A-Z Guide to over 160 Different Alternative Therapies. La Mesa, CA: Halcyon; 1993.

Alternative Medicine: Expanding Medical Horizons. A Report to the National Institutes of Health on Alternative Medical Systems and Practices in the United States. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1994.

Hafner AW, Carson JG, Zwicky JF, eds. Guide to the American Medical Association Historical Health Fraud and Alternative Medicine Collection. Chicago: American Medical Assoc; 1992.

Segen JC. Dictionary of Alternative Medicine. Stamford, CT: Appleton & Lange; 1998.

McGuire MB. Ritual Healing in Suburban America. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Univ Pr; 1988.

English-Lueck JA. Health in the New Age: A Study in California Holistic Practices. Albuquerque, NM: Univ of New Mexico Pr; 1990.

Report on alternative medicine. British Medical Association. In: Saks M, ed. Alternative Medicine in Britain. Oxford: Clarendon Pr; 1992.

Newman Turner R. A proposal for classifying complementary therapies. Complement Ther Med. 1998;6:141-3.

Furnham A. How the public classify complementary medicine: a factor analytic study. Complement Ther Med. 2000;8:82-7. [PMID: 0010859600]

Complementary medicine: time for critical engagement [Editorial]. Lancet. 2000;356:2023. [PMID: 0011145481]

Kemper KJ. Separation or synthesis: a holistic approach to therapeutics. Pediatr Rev. 1996;17:279-83. [PMID: 0008758669]

Pietroni PC. Beyond the boundaries: relationship between general practice and complementary medicine. BMJ. 1992;305:564-6. [PMID: 0001393039]

Kaptchuk TJ, Eisenberg DM. The persuasive appeal of alternative medicine. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:1061-5. [PMID: 0009867762]

Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Van Rompay M, Kessler RC.

Trends in Alternative Medicine Use in the United States, 1990 to 1997:

Results of a Follow-up National Survey

JAMA 1998 (Nov 11); 280 (18): 1569–1575Cooter R. Bones of contention? Orthodox medicine and the mystery of the bone-setter’s craft. In: Bynum WF, Porter R, eds. Medical Fringe & Medical Orthodoxy, 1750-1850. London: Croom Helm; 1987.

Ted J. Kaptchuk, OMD; David M. Eisenberg, MD

Chiropractic. Origins, Controversies and Contributions

Archives of Internal Medicine 1998 (Nov 9); 158 (20): 2215-2224Wardwell WI. Chiropractic: History and Evolution of a New Profession. St. Louis: Mosby–Year Book; 1992.

Coulehan JL. Chiropractic and the clinical art. Soc Sci Med. 1985;21:383- 90. [PMID: 0002931804]

National Center for Health Statistics. Office Visits to Osteopathic Physicians, Jan.-Dec. 1974: Provisional Data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1975.

Johnson SM, Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC. Variables influencing the use of osteopathic manipulative treatment in family practice. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1997; 97:80-7. [PMID: 0009059002]

Kaptchuk TJ. The Web That Has No Weaver: Understanding Chinese Medicine. Chicago: Contemporary Books; 2000.

Mitchell BB. Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine Laws. Washington, DC: National Acupuncture Foundation; 1997.

Ernst E, Kaptchuk TJ. Homeopathy revisited. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156: 2162-4. [PMID: 0008885813]

Kaufman M. Homeopathy in America: The Rise and Fall of a Medical Heresy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ Pr; 1971.

Gort EH, Coburn D. Naturopathy in Canada: changing relationships to medicine, chiropractic and the state. Soc Sci Med. 1988;26:1061-72. [PMID: 0003293229]

Baer HA. The potential rejuvenation of American naturopathy as a consequence of the holistic health movement. Med Anthropol. 1992;13:369-83. [PMID: 0001545694]

Eisenberg DM.

Advising Patients Who Seek Alternative Medical Therapies

Annals of Internal Medicine 1997 (Jul 1); 127: 61-69Knapp JE, Antonucci EJ. A National Study of the Profession of Massage Therapy/Bodywork. Princeton, NJ: Knapp and Assoc; 1990.

Tappen FM. Healing Massage Techniques: Holistic, Classic and Emerging Methods. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange; 1988.

Good BJ, Good MJ. Alternative Health Care in a California Community. Report No. 8. A Study Conducted for the California Board of Medical Quality Assurance by the Public Affairs Research Group. Sacramento: Public Regulation of Health Care Occupations in California; 1981.

Rywerant Y. The Feldenkrais Method. San Francisco: Harper & Row; 1983.

Leibowitz J, Connington B. The Alexander Technique. New York: Harper & Row; 1990.

Goldstein MS, Jaffe DT, Sutherland C, Wilson J. Holistic physicians: implications for the study of the medical profession. J Health Soc Behav. 1987;28: 103-19. [PMID: 0003611700]

Yahn G. The impact of holistic medicine, medical groups, and health concepts. JAMA. 1979;242:2202-5. [PMID: 0000490807]

Weil A. Spontaneous Healing. New York: Knopf; 1995.

Dossey L. Meaning & Medicine. New York: Bantam; 1991.

Gordon JS. Manifesto for a New Medicine. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1996.

Chopra D. Quantum Healing: Exploring the Frontiers of Mind/Body Medicine. New York: Bantam; 1989.

Kaptchuk TJ, Eisenberg DM. The health food movement [Editorial]. Nutrition. 1998;14: 471-3. [PMID: 0009614317]

Kandel RF. Rice, ice cream, and the guru: decision-making and innovation in a macrobiotic community [Dissertation]. New York: State Univ of New York; 1976.

Kirschner HE. Live Food Juices. Monrovia, CA: Kirscher; 1991.

Deutsch RM. The New Nuts among the Berries. Palo Alto, CA: Deutsch; 1977.

Melton JG. New Age Encyclopedia. Detroit: Gale Research; 1990.

Ellwood RS. Alternative Altars: Unconventional and Eastern Spirituality in America. Chicago: Univ of Chicago Pr; 1979.

Barnes LL. The psychologizing of Chinese healing practices in the United States. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1998;22:413-43. [PMID: 0010063466]

Oppenheim J. The Other World: Spiritualism and Psychical Research in England, 1850-1914. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ Pr; 1988.

Glik DC. Symbolic, ritual and social dynamics of spiritual healing. Soc Sci Med. 1988;27:1197-206. [PMID: 0002462751]

Fuller RC. Mesmerism and the American Cure of Souls. Philadelphia: Univ of Pennsylvania Pr; 1982.

Kaptchuk TJ. History of vitalism. In: Micozzi MS, ed. Fundamentals of Complementary and Alternative Medicine. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2001.

Feher S. Who holds the cards? Women and new age astrology. In: Lewis JR, Melton JG, eds. Perspectives on the New Age. Albany, NY: State Univ of New York Pr; 1992.

Krieger D, Peper E, Ancoli S. Therapeutic touch: searching for evidence of physiological change. Am J Nurs. 1979;79:660-2. [PMID: 0000373441]

Zefron LJ. The history of the laying-on of hands in nursing. Nurs Forum. 1975;14:350-63. [PMID: 0000772630]

Miura K. The revival of qi: qigong in contemporary China. In: Kohn L, ed. Taoist Meditation and Longevity Techniques. Ann Arbor, MI: Center for Chinese Studies, Univ of Michigan; 1989.

Yasuo Y. The Body, Self-Cultivation and Ki-Energy. Albany, NY: State Univ of New York Pr; 1993.

Levin JS, Coreil J. ‘New age’ healing in the U.S. Soc Sci Med. 1986;23:889- 97. [PMID: 0003798167]

Johnson KP. Edgar Cayce in Context. Albany, NY: State Univ of New York Pr; 1998.

Kerr H, Crow CL, eds. The Occult in America: New Historical Perspectives. Urbana, IL: Univ of Illinois Pr; 1983.

Easthope G. Healers and Alternative Medicine: A Sociological Examination. Hants, England: Aldershot; 1986.

Van Praag J. Talking to Heaven: A Medium’s Message of Life after Death. New York: Dutton; 1997.

Parker GT. Mind Cure in New England from the Civil War to World War I. Hanover, NH: Univ Pr of New England; 1973.

Braden CS. Spirits in Rebellion: The Rise and Development of New Thought. Dallas: Southern Methodist Univ Pr; 1963.

Judah JS. The History and Philosophy of the Metaphysical Movements in America. Philadelphia: Westminster Pr; 1967.

Kirmayer LJ. Mind and body as metaphors: hidden values in biomedicine. In: Lock M, Gordon D, eds. Biomedicine Examined. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1988.

Osherson S, AmaraSingham L. The machine metaphor in medicine. In: Mishler EG, AmaraSingham L, Osherson SD, Hauser ST, Waxler NE, Liem R. Social Contexts of Health, Illness, and Patient Care. New York: Cambridge Univ Pr; 1981.

Cassileth BR, Chapman CC. Alternative cancer medicine: a ten-year update. Cancer Invest. 1996;14:396-404. [PMID: 0008689436]

Ko CY, Tong J, Lehman RE, Shelton AA, Schrock TR, Welton ML. Biofeedback is effective therapy for fecal incontinence and constipation. Arch Surg. 1997;132:829-34. [PMID: 0009267265]

Eisenberg DM, Delbanco TL, Berkey CS, Kaptchuk TJ, Kepelnick B, Kuhl J, et al. Cognitive behavioral techniques for hypertension: are they effective? Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:964-72. [PMID: 0008489111]

Linden W, Chambers L. Clinical effectiveness of non-drug treatment for hypertension: a meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 1994;16:35-45.

Herink R, ed. The Psychotherapy Handbook. New York: New American Library; 1980.

Karasu TB. The specificity versus nonspecificity dilemma: toward identifying therapeutic change agents.AmJ Psychiatry. 1986;143:687-95. [PMID: 0003717390]

Uva JL. Alcoholics anonymous: medical recovery through a higher power. JAMA. 1991;266:3065-7. [PMID: 0001820486]

Jones RK. Sectarian characteristics of Alcoholics Anonymous. Sociology. 1970;4:181-95.

U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment. Unconventional Cancer Treatments. Washington, DC: U.S Government Printing Office; 1990.

Lerner M. Choices in Healing: Integrating the Best of Conventional and Complementary Approaches to Cancer. Cambridge, MA: MIT Pr; 1994.

Laetz T, Silberman G. Reimbursement policies constrain the practice of oncology. JAMA. 1991;266:2996-9. [PMID: 0001820471]

O’Connor BB. Healing Traditions: Alternative Medicine and the Health Professions. Philadelphia: Univ of Pennsylvania Pr; 1995.

Cohen C, Shevitz A, Mayer K. Expanding access to investigational new therapies. Prim Care. 1992;19:87-96. [PMID: 0001594704]

Barrett S. Commercial hair analysis. Science or scam? JAMA. 1985;254: 1041-5. [PMID: 0004021042]

Ernst E. Iridology: a systematic review. Forsch Komplementa¨rmed. 1999;6: 7-9. [PMID: 0010213874]

Ernst E. Chelation therapy for peripheral arterial occlusive disease: a systematic review. Circulation. 1997;96:1031-3. [PMID: 0009264515]

Harwood A, ed. Ethnicity and Medical Care. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ Pr; 1981.

Harwood A. Puerto Rican spiritism. Part I—Description and analysis of an alternative psychotherapeutic approach. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1977;1:69-95 [PMID: 0000756355]

Fisch S. Botanicas and spiritualism in a metropolis. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1968;46:377-88. [PMID: 0005672031]

Trotter RT II, Chavira JA. Curanderismo: Mexican American Folk Healing. Athens, GA: Univ of Georgia Pr; 1981.

Martinez C, Martin HW. Folk diseases among urban Mexican-Americans. Etiology, symptoms, and treatment. JAMA. 1966;196:161-4. [PMID: 0005952114]

Brown KM. Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn. Berkeley, CA: Univ of California Pr; 1991.

Scott CS. Health and healing practices among five ethnic groups in Miami, Florida. Public Health Rep. 1974;89:524-32. [PMID: 0004218901]

Fuchs M, Bashshur R. Use of traditional Indian medicine among urban native Americans. Med Care. 1975;13:915-27. [PMID: 0001195900]

Fadiman A. The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down. A Hmong Child, Her American Doctors, and the Collision of Two Cultures. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux; 1997.

Mathews HF. Rootwork: description of an ethnomedical system in the American South. South Med J. 1987;80:885-91. [PMID: 0003603109]

Snow LF. Sorcerers, saints and charlatans: black folk healers in urban America. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1978;2:69-106. [PMID: 0000699623]

Jacobs CF. Healing and prophecy in the black Spiritual churches: a need for re-examination. Med Anthropol. 1990;12:349-70. [PMID: 0002287192]

Goldman B. Ayurvedism: eastern medicine moves west. CMAJ. 1991;144: 218-21. [PMID: 0001986838]

Anderson J. Far side of faith: Tibetan medicine’s miracle cures. Newsday. 5 Nov 1997:B10.

Albanese CL. Nature Religion in America: From the Algonkian Indians to the New Age. Chicago: Univ of Chicago Pr; 1990.

Cavender AP. Theoretic orientations and folk medicine research in the Appalachian South. South Med J. 1992;85:170-8. [PMID: 0001738884]

Levine HD. Folk medicine in New Hampshire. N Engl J Med. 1941;224: 487-92.

Hand WD. The folk healer: calling and endowment. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 1971;26:263-75. [PMID: 0004938939]

Cook C, Baisden D. Ancillary use of folk medicine by patients in primary care clinics in southwestern West Virginia. South Med J. 1986;79:1098-101. [PMID: 0003749993]

Rinzler CA. Feed a Cold, Starve a Fever: A Dictionary of Medical Folklore. New York: Facts on File; 1991.

Saketkhoo K, Januszkiewicz A, Sackner MA. Effects of drinking hot water, cold water, and chicken soup on nasal mucus velocity and nasal airflow resistance. Chest. 1978;74:408-10. [PMID: 0000359266]

Pachter LM. Culture and clinical care. Folk illness beliefs and behaviors and their implications for health care delivery. JAMA. 1994;271:690-4. [PMID: 0008309032]

Hufford DJ. Folk medicine and health culture in contemporary society. Prim Care. 1997;24:723-41. [PMID: 0009386253]

Curry P, ed. Astrology, Science and Society: Historical Essays. Woodbridge, Suffolk, England: Boydell Pr; 1987.

Dick HG. Students of physic and astrology: a survey of astrological medicine in the age of science. Journal of the History of Medicine. 1946;13:300-15.

Gebhard B. The interrelationship of scientific and folk medicine in the United States of America since 1850. In: Hand WD, ed. American Folk Medicine. Berkeley, CA: Univ of California Pr; 1976.

Helman CG. “Feed a cold, starve a fever”—folk models of infection in an English suburban community, and their relation to medical treatment. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1978;2:107-37. [PMID: 0000081735]

Koenig HG, Moberg DO, Kvale JN. Religious activities and attitudes of older adults in a geriatric assessment clinic. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36:362-74. [PMID: 0003351176]

Yates JW, Chalmer BJ, St. James P, Follansbee M, McKegney FP. Religion in patients with advanced cancer. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1981;9:121-8. [PMID: 0007231358]

Numbers RL, Amundsen DW. Caring and Curing: Health and Medicine in the Western Religious Traditions. New York: Macmillan; 1986.

Johnson DM. Religion, health and healing: findings from a southern city. Sociological Analysis. 1986;47:66-73.

King DE, Sobal J, DeForge BR. Family practice patients’ experiences and beliefs in faith healing. J Fam Pract. 1988;27:505-8. [PMID: 0003264015]

Amundsen DW. Medicine and faith in early Christianity. Bull Hist Med. 1982;56:326-50. [PMID: 0006753984]

Ferngren GB. Early Christianity as a religion of healing. Bull Hist Med. 1992;66:1-15. [PMID: 0001559026]

Harrell DE. All Things Are Possible: The Healing and Charismatic Revivals in Modern America. Bloomington, IN: Indiana Univ Pr; 1975.

Csordas TJ. The Sacred Self: A Cultural Phenomenology of Charismatic Healing. Berkeley, CA: Univ of California Pr; 1994.

Dowling SJ. Lourdes cures and their medical assessment. J R Soc Med. 1984;77:634-8. [PMID: 0006384509]

Kelsey MT. Healing and Christianity. New York: Harper & Row; 1973.

Fox M. Conflict to coexistence: Christian Science and medicine. Med Anthropol. 1984;8:292-301. [PMID: 0006399347]

Schoepflin RB. Christian Science healing in America. In: Gevitz N, ed. Other Healers: Unorthodox Medicine in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ Pr; 1988.

Mann MC, Votto J, Kambe J, McNamee MJ. Management of the severely anemic patient who refuses transfusion: lessons learned during the care of a Jehovah’s Witness. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:1042-8. [PMID: 0001307705]

Singelenberg R. The blood transfusion taboo of Jehovah’s Witnesses: origin, development and function of a controversial doctrine. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31: 515-23. [PMID: 0002218633]

Hexham I. The evangelical response to the New Age. In: Lewis JR, Melton JG, eds. Perspectives on the New Age. Albany, NY: State Univ of New York Pr; 1992.

Kaptchuk TJ, Crocher M. The Healing Arts: A Journey through the Faces of Medicine. London: British Broadcasting; 1986.

Kleinman AM. Medicine’s symbolic reality. On a central problem in the philosophy of medicine. Inquiry. 1973;16:206-13

Return to EISENBERG's CAM ARTICLES

Since 9-01-2001

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |