Is Chiropractic Pediatric Care Safe?

A Best Evidence TopicThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Clinical Chiropractic 2011 (Sep); 14 (3): 97–105 ~ FULL TEXT

Matthew F. Doyle

Objective To review the literature as to the safety of paediatric chiropractic care and to offer recommendations for congruent consistent terminology use.

Design Best Evidence Topic.

Methods Formulation of a clinical question based on a patient query. PubMed, Index to Chiropractic Literature and the Cochrane Library were searched on the 19th of June 2010. A total of nine specifically relevant articles were retrieved and critically reviewed.

Results The reviewed published chiropractic literature suggests a rate of 0.53% to 1% mild adverse events (AE) associated with chiropractic paediatric manipulative therapy (PMT). Put in terms of individual patients, between one in 100 to 200 patients presenting for chiropractic care; or in terms of patient visits, between one mild AE per 1310 visits to one per 1812 visits. For a comparison, Osteopathic PMT have a reported rate of 9%, and medical practitioners utilising PMT under the auspices of ‘chiropractic therapy’ have reported a rate of 6%. No serious AE has been reported in the literature since 1992 and no death possibly associated with chiropractic PMT has been reported for over 40 years.

Conclusion The application of modern chiropractic paediatric care within the outlined framework is safe. A reasonable caution to the parent/guardian is that one child per 100 to 200 attending may have a mild adverse events, with irritability or soreness lasting less than 24 hours, resolving without the need for additional care beyond initial chiropractic recommendations.

KEYWORDS Safety; Chiropractic; Paediatric/paediatric; Adverse events; Adjustment/paediatric manipulative therapy

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Clinical scenario

Mr. G, a financial planner, has attended your clinic for a number of years. He mentioned recently his 3-year-old daughter has experienced several ear infections (diagnosed as chronic otitis media by their family medical practitioner) and his 12-year old son has been complaining of neck and low back aches after pre-season rugby training (diagnosed as mechanical neck and low back pain by their family medical practitioner). On their last visit to the medical centre his daughter was prescribed a 5-day course of antibiotics (having used a watchful waiting approach for the initial cases of otitis media), and his son was recommended low dose symptomatic usage of non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs. At that time he stated his concerns to his medical practitioner about his children using drugs and asked whether chiropractic care and his children being checked and adjusted if necessary may help. His medical practitioner said he had some reserves about safety of chiropractic care for children; however, the decision was up to Mr. G. Mr. G asks you if chiropractic is safe for his children.

Structured clinical question

The most common clinical intervention used by the chiropractor is the adjustment. This specific term is commonly grouped together under the more generic terms chiropractic paediatric manipulation or chiropractic paediatric manipulative therapy (PMT). For the purposes of this review the age limit was set at 18.

In the paediatric population (aged 0–18 years old) [patient] is the chiropractic adjustment (paediatric manipulative therapy) [intervention] safe in terms of avoidance of adverse events [outcome]

Search strategy and outcome

PubMed, the Index to Chiropractic Literature (ICL), and the Cochrane Library were searched with the terms chiropractic paediatric manipulation on June 19th 2010.

PubMed search: CHIROPRACTIC AND MANIPULATION AND PAEDIATRIC, with limitations set to humans, English, all child: 0–18 years.

("chiropractic" [MeSH Terms] OR "chiropractic" [All Fields]) AND MANIPULATION[All Fields] AND PAEDIATRIC [All Fields] AND ("humans" [MeSH Terms] AND English [lang] AND ("infant" [MeSH Terms] OR "child" [MeSH Terms] OR "adolescent" [MeSH Terms]))

This resulted in 12 articles. Four articles dealing specifically with safety or adverse events were retrieved, including an original article prospective survey, [1] a Delphi consensus best practice recommendation, [2] a retrospective survey, [3] and a systematic review. [4] ICL search: CHIROPRACTIC AND MANIPULATION AND PAEDIATRIC with limitations for peer review only. This returned 30 articles; the four articles retrieved from PubMed were contained in this list. A further five articles were retrieved, which made reference to safety, harm, or adverse events in the titles. These consisted of three commentaries on the safety of PMT [5-7] and reviews of the literature. [8, 9]

Cochrane Library search: CHIROPRACTIC AND MANIPULATION AND PAEDIATRIC with limits set to search all text. No new relevant articles were retrieved.

Literature review

Reviews

The first in-depth academic review of literature relating to the safety of paediatric chiropractic care was by Pistolese in 1998. [9] He noted two case reports in the literature. Firstly, Zimmerman et al. [10] in 1978 documented a seven-year-old boy suffering headaches and transient cranial nerve deficits after vigorous gymnastics and repeated manipulations of the cervical spine by the chiropractor. Pre-existing symptoms, which could be noted as minor adverse events (AE) post PMT, are present prior to PMT, and are severely exacerbated following both episodes of chiropractic PMT. This clarification is important as it demonstrates the role of pre-existing health concerns in patient outcomes. The second case, Shafrir and Kaufman in 1992, [11] discussed the case of a child with a spinal cord tumour (astrocytoma) who presented to a chiropractor complaining of torticollis. Following chiropractic care, the child became quadriplegic, allegedly as a result of cervical manipulation.

Pistolese states that:"while astrocytoma has been reported to be a congenital condition in numerous medical publications, there exists no evidence to support the claim of a complication arising as a result of chiropractic care. Once again, this report is speculative at best lacking any scientific evidence to support the claim."

Case reporting is important for health care professionals to raise awareness in the field of common presentations and outlier results, positive or negative. There is no suggestion that chiropractic care caused the astrocytoma; however, biological plausibility remains that the chiropractor’s treatment was a factor in the provocation of quadriplegia. This evolved to paraplegia eighteen months postoperatively. [4]

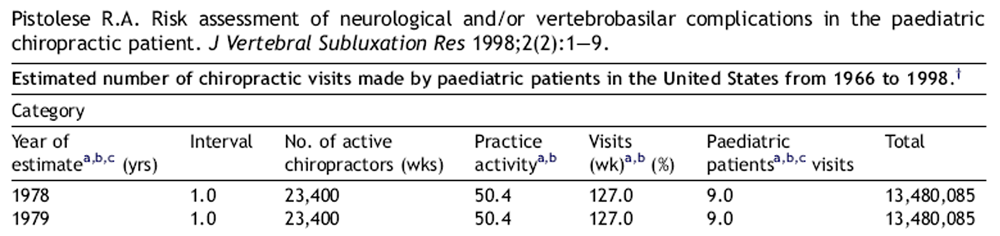

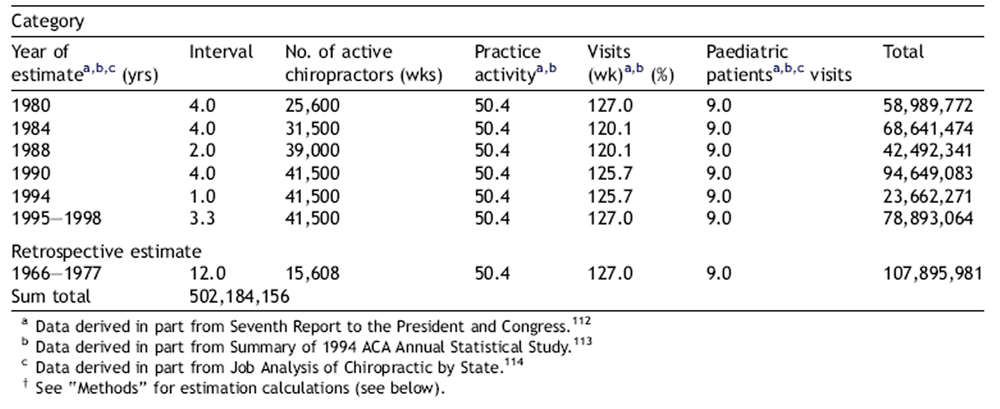

The Pistolese data was collated by a quasi meta-nalysis based on three documents including the 1990 Seventh Report to the President and Congress on the Status of Health Personnel in the United States, the summary of 1994 American Chiropractic Association (ACA) Annual Statistical Study and the 1994 Job Analysis of Chiropractic by State by the National Board of Chiropractic Examiners (NBCE), and the two case reports (Appendix 1).

Many weaknesses are noted with the use of this data. Firstly, the definition of a "quasi meta-analysis" is uncertain. Secondly, there were issues with the basic documents used, the Health Personnel report and ACA study including but not limited to: a lack of consideration of the impact of response rate, reporting the actual number of survey instruments mailed, socio-demographics of the respondents versus non-respondents and validation of the questionnaires used themselves.

The study utilised the databases Medline and MANTIS and the timeframe between 1966 and 1998. Specific Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) keywords including chiropractic, adjustment, manipulation, complication and child/children were used, which retrieved the two reports. The calculated estimate of paediatric chiropractic visits for the time frame between 1966 and 1998 was 502,184,156. With two reported cases of serious AE, an estimated risk to the chiropractic paediatric patient for a neurological and/or vertebrobasilar incident to occur is given as approximately 1 in 250 million paediatric visits.

Vohra and colleagues in 2007 [4] next published the most comprehensive systematic review of literature related to paediatric adverse events and PMT. Their inclusion criteria were: a primary investigation of spinal manipulation; a study population aged 18 or younger; and reporting on adverse events. All relevant reports, regardless of publication status, were retrieved following a comprehensive search developed in collaboration with a clinical librarian and content experts. Electronic databases were reviewed containing literature spanning 1900–2004 including Central (second quarter 2004), Medline (1966–2004), PubMed (1966–2004), Embase (1988–2004), CINAHL (1982–2004), AltHealthWatch (1990–2004), MANTIS (1900–2005), and ICL (1985–2004). No rationale is given why the MANTIS database was searched to 2005 not 2004.

A total of 13,916 articles, retrieved from the electronic and grey literature, were considered and the authors identified 14 cases of direct AE. One of those (Held, 1966 [4]) was an examination of the cervical spine performed by a medical doctor. Humphreys [8] appropriately contends that examination of the cervical spine is not done with therapeutic intent thereby excluding it by definition from PMT. The article by Jacobi (2001 [4]), states the practitioner was a physiotherapist and the serious AE was death. The description of the spinal manipulation involving several ‘strong rotation and reclination movements’ is outside the realm of any currently recommended chiropractic PMT. [2] One of the case series by Ragoet (1969 [12]) has death as a sequelae; it does not state what type of practitioner applied the PMT. [4] Only one of the three reported cases by Ragoet specifically names a chiropractor as the practitioner. The literature is replete with examples of the term chiropractic or chiropractic manipulation describing the technique utilised by a practitioner other than a chiropractor (Terrett, 1996 [13]; Koch et al., 2002 [14]; Biedermann, 1992 [15]). The clinical question is directed at the safety of chiropractic and, therefore, ten reports involving chiropractors are pertinent and discussed herein. Alcantara [5] provided a critical review of these cases with an in-depth review of the referred incidents and articles and is used as the structure for this section.

Three minor adverse events are reported within two articles. The first, by Sawyer et al. (1999 [5]), contains the parental report of ‘one child with some mid back soreness after one treatment that resolved after a few days, and another child was reported by the parent as being irritable for a short time after treatment’. A lack of definition of what ‘irritable’ means and the context it is used in raises questions of the appropriateness to report it as a minor AE. A myriad of uncontrolled factors could lead the parent to report their child being irritable.

The second study by Klougart et al. (1996 [5]) reports a ten-year-old male who lost consciousness after the adjustment (PMT in the form of a Gonstead Technique adjustment to C7/T1) on two separate occasions.

Alcantara makes the comment:‘What of syncope following the adjustment? I know of several chiropractors with patients who demonstrate a vaso-vagal response to SMT in the cervical spine resulting in ‘fainting’ or loss of consciousness. In these cases, the patient indicated a history of ‘fainting’ with a turning of the head and neck in various situations with no adverse events. Obviously, the 10-year-old patient or his parents were not dissuaded from care following the first event of syncope. Therefore, the interpretation on the part of Vohra and her colleagues of an adverse event in this situation is also questionable.’

Syncope is a known and not uncommon response to head and neck manoeuvres; however, it is unclear whether or not Klougart et al. [5] are referring to this specifically. The interpretation by Vohra et al. [4] may be questionable; however, in light of no other evidence given to the contrary, a listing as a minor AE seems reasonable.

Leboeuf et al. (1991 [4]) reported two patients having moderate AE in a study of 171 enuretic children and their response to chiropractic care.

These were reported as:‘one child developed severe headaches and a stiff neck after treatment of the cervical spine and neither the child nor the parents could recall any previous symptoms from the area. The condition improved gradually over the next two weeks during which soft tissue therapy was administered and the child refrained from active physical activity. The other subject developed acute pain in the lumbar spine similar to the case described previously and recovered while gentle treatment was provided for symptomatic relief’.

The definition given by Vohra et al. [4] for a moderate AE is ‘transient disability, involving seeking medical care but not hospitalisation’. Their definition of a minor AE is ‘self-limited, did not require additional medical care’. Alcantara5 contends that by definition these two events should be categorised as minor. A difference appears in what Vohra4 and Alcantara5 consider ‘medical care’. If medical care is considered to be care administered by a medical professional, as opposed to care given by a chiropractor, then the two cases are incorrectly listed as moderate and should have been listed as minor adverse events.

This leaves five AE listed as serious by Vohra, which were commented on by Alcantara. [4] The French article by Ragoet (1969 [12]) was not retrievable and hence not reviewed. The remaining four case reports4 describe serious AE temporally related to chiropractic care in patients with underlying pathology. It may be suggested that the initial description of the cases, pathology, treatment and outcome is biased to lay the predominant blame for the AE on chiropractic intervention. The description of technique given in two of the cases does not resemble any common current chiropractic approach to PMT, and three cases demonstrate recent prior trauma that may have contributed to the development of symptomatology.

Vohra et al. [4] also identified twenty cases from three references of indirect AE related to misdiagnosis or delayed treatment. Alcantara’s5 commentary on these cases has an emotional tone to it; however, he makes the salient point that biases may be seen in the presentation of these cases of missed or delayed diagnosis. As a practicing paediatric chiropractor and the research director for the International Chiropractic Paediatric Association (ICPA), Alcantara does have inherent bias towards the benefits of PMT. The noting of bias is always important when critically reviewing an article. The most important question to ask here, with a framework of ‘first, do no harm’, is what is the risk/benefit ratio of accepting a paediatric patient for chiropractic care? The missed or delayed diagnosis cases bring to light the importance of relevant quality chiropractic paediatric education. This ensures a relevant framework of paediatric knowledge, including an ability to read and critically review literature, from which to better inform safe chiropractic paediatric practice.

Vohra and colleagues opine that Pistolese’s estimate of the risk of neurologic and/or vertebrobasilar complications from PMT of one in two hundred and fifty million paediatric visits is inaccurate and likely underestimates risk. With a self-stated acknowledgement that their search strategy was more comprehensive they were, however, unwilling to create a risk estimate with an uncertain denominator. This is disappointing for the clinician. Best estimates by educated researchers of risk can be useful to assist clinical decision-making. Given the search covered an 104-year period, and returned only five serious AE specifically temporally associated with a chiropractor, the possibility is such that this risk may in fact be less than estimated by Pistolese.

Following discussion of the risk factors predisposing a child to AE related to PMT, the possibility of under-reporting, and the reported low level of CAM practitioner training in paediatrics, Vohra et al. [4] comment that ‘despite what some have advised, many children continue to visit chiropractors, and many chiropractors continue to treat children’. In the context of delayed diagnosis of a serious underlying pathology or condition needing referral to an appropriate medical practitioner, Humphreys [8] notes a study of Boston chiropractors where 17% would continue sole treatment in a hypothetical case of a two-week fever in a neonate. This is reported as conflicting with current medical guidelines for treatment of paediatric cases of fever. This may be one among many such hypothetical cases. The commentary from both Humphreys [8] and Vohra et al. [4] would suggest a clear and present danger to an appreciable percentage of the paediatric population whose parents choose chiropractic care for their children. When considering the information above, and with no serious AE temporally related to chiropractic care published within the peerreviewed literature from 1992 to July 2010, the question may be raised as to the appropriateness of the closing statement by Vohra:‘in the interim, clinicians should query parents and children about CAM usage and caution families that although serious adverse events may be rare, a range of adverse events or delay in appropriate treatment may be associated with the use of spinal manipulation in children’.

A systematic review is only as strong as the quality of the research that is reviewed. There is a paucity of specific chiropractic paediatric literature relating to adverse events on a scale beyond the case report.

Chiropractic studies

Miller and Benfield [3] and Alcantara et al. [1] provide the first specific chiropractic literature investigating adverse events directly within the chiropractic profession. Alcantara et al. [1] completed a retrospective cross sectional survey of practitioners specifically interested in the care of the paediatric population, whilst Miller and Benfield [3] published a retrospective case file review.

The purpose of Miller and Benfield’s [3] study was to identify any AE from chiropractic care occurring in the paediatric patient less than three years of age and to evaluate the risk of complication in that group arising from care. This is the first published peer reviewed study by chiropractors of chiropractic paediatric patients receiving chiropractic care in a chiropractic (teaching) clinic investigating AE. At the time of publication, the chiropractic profession was 113 years old. With paediatric care being noted as part of the chiropractic caseload in the literature as early as 1910, this borders on reprehensible for a profession interested in the health and wellbeing of children. Although there was many weaknesses in the study, such as retrospective reporting, lack of random file selection, student treatment versus practitioner treatment, and the reputation of the clinic for successfully taking care of infants, etc., it was an important first step. A total of 781 paediatric patients were reported on, with 462 (59.15%) male and 319 (40.85%) female, and most (73.5%) 12 weeks or younger. Following the dismissal of 82 (10.5%) to seek other care, the most common reasons for presentation were irritability or colic attributed to spinal biomechanical disorder, often attributed to birth trauma. Seven reactions to treatment were reported. Of these, four were classified as actual negative reactions to care. This resulted in a mild AE rate of one per every 100 children presenting for chiropractic care, or one mild AE in approximately 1300 chiropractic treatments.

Inherent difficulties arise when reporting on AE in a paediatric age group due to the child’s inability to communicate as an adult, and the use of parent opinion for subjective outcome reporting. The study was done at a teaching clinic, which creates weaknesses for the study. Students may not be most accurate at identifying problems with the child; they may not be accurate in reporting, with a potential for leaning their report to what they think their tutor may want to hear. They can only perceive the case through the educational framework that they have been given, which may bias them to a particular style of thinking. To help develop an appropriate standard of care, the profession should establish guidelines, initially through a Delphi process, for age appropriate delivery of an adjustive force. This should include a wide range of the profession, including practitioners with appropriate practice experience and post graduate paediatric education, educators, researchers, and technique experts.

Alcantara et al. [1] utilise a retrospective crosssectional survey design to elicit descriptive information regarding the practice of paediatric chiropractic, including its safety and effectiveness. To accurately study both safety and effectiveness a randomised controlled trial design is appropriate whereas a survey cannot objectively address those questions. The survey does provide useful data to better inform the field practitioner, and assist orienting researchers in appropriate directions. A weakness noted is bias with all authors being involved in the ICPA. Of those 5,438 treatments given, only three mild adverse events, reported as treatment-associated aggravations, were noted. Usefully, they describe the attending chiropractor’s response to these, which included: reexamination and application of different PMT, modification of the technique rendered, or modification of the spinal segment involved. No treatment-related complications (moderate to severe AE) were noted by the patients or their parents/guardians. The authors’ report 0.83% of paediatric patients’ visits, or one in 1,812 patient visits, resulted in a mild AE following chiropractic PMT.

Humphreys, [8] in an update review of the articles discussed above, reports on a 2006 retrospective review by Haynes and Bezilla of osteopathic paediatric manipulative therapy (OPMT). They included 346 case files from which a mild AE rate of 9% was established. The authors are reported to have concluded that their study supports OPMT as a safe treatment for the paediatric population. In his discussion, Humphreys makes comment that the application of MT, particularly PMT, continues to be controversial, though he does not state from where this controversy stems. Miller [6] reports a summary of articles relating to safety of chiropractic treatment for paediatric patients. Interestingly two studies (Koch et al., 2002; Biedermann, 1992) are reviewed with a total of 1,295 paediatric patients receiving ‘chiropractic therapy’ from medical doctors. A mild AE (reported as mild side effect) rate of 6% was noted. Two important points are noted here by Miller. [6] Firstly, the ‘chiropractic’ PMT given by medical doctors were described as ranging from 30 to 70 N with an average of 50 N (recommended in chiropractic PMT = 2 N or less under 12 weeks of age [6]). Secondly, these events were preferentially noted in those younger than 12 weeks. Koch reports 12.1% of the infants experienced bradycardia, flush, and apnoea after manipulation, which the authors considered to be normal adaption of the autonomic nervous system to MT. According to the varied published criteria in the chiropractic literature these would be considered adverse events in the chiropractic clinical setting.

Discussion

Risk rates

The reviewed published chiropractic literature suggests a rate of 0.53% to 1% mild AE associated with chiropractic PMT. To put this in terms of individual patients, the risk is between one in 100–200 patients presenting for chiropractic care; or in terms of patient visits, between one mild AE per 1,310 visits to one per 1812 visits. For a comparison, OPMT have a reported rate of 9%, and medical practitioners utilising PMT under the auspices of ‘chiropractic therapy’ have reported a rate of 6%.

For comparison, the risk of mild AE in the adult population is reported as between 31 and 50% per patient (Carnes et al. [23]). In their meta-analysis of studies, Carnes and others pooled data to compare AE. Their findings showed more AE for MT compared to general medical practitioner care, about the same number compared to exercise, but less than drug therapy. The authors concluded the relative risk of having a minor or moderate AE after high velocity thrust spinal manipulation was significantly less than taking the medication often prescribed for these conditions.

Terminology

The review conducted of the current literature has identified different terminologies used for negative events, with different definitions within each, making it difficult to look at cross correlations. These include the descriptors side effects, aggravations, complications, and AE. Epistemologically the use of side effects to describe outcomes of care is inaccurate. When considering the scientific method it is accurate to describe cause and effect, not cause, effect, and side effect. The descriptors used by Alcantara et al. [1] are overly wordy and less useful for the negative events associated with care. The terminology adopted by Vohra et al. [4] of AE post-PMT are epistemologically appropriate, with categories of minor, moderate, and severe. For better continuity with the use of minor, the severe category would be called major. Miller and Benfield [3] adopted the terms AE for their study, and their use of mild, moderate, and severe appear the most congruent descriptor verbiage. Appendix 2 lists the different definitions used. A caveat to the terminology use is whether it is appropriate to list mild transient symptoms as adverse events, as was noted in the Koch study. For example these mild symptoms could be viewed similarly to those associated with the symptoms of muscle soreness following intensive exercise; i.e. they could both be normal physiological adaptive changes, not adverse events. However, based on the current published zeitgeist, the following definitions are offered as an integrated and clinically useful standard reporting terminology for AE.Mild – defined as irritability, soreness, lasting <24 h, requiring no additional treatment to current chiropractic care plan.

Moderate – defined as acute pain increase, such as headache, back pain; transient disability, requiring additional chiropractic or medical treatment on top of current care plan.

Severe – defined as an adverse event following and due to treatment, requiring hospitalisation.

Technique and safety

Hawk et al. [2] and Miller [6] give a broad overview of current chiropractic paediatric care and technique. Nowhere within the reviewed literature, or within this author’s chiropractic paediatric education (undergraduate, professional, or post-graduate studies) has it been taught or suggested that repetitive rotational manual manipulation, or any cervical adjustment with an extension emphasis, is appropriate or recommended for a paediatric patient. The serious AE listed by Vohra et al. [4] appear to either not state the technical approach to address the spine, or list it as ‘several strong rotation and reclination movements’, ‘flexion, extension, axial loading and unloading’, or ‘rapid manual rotation of the head with flexion and hyperextension’. This has had little mention within the discussion of the Vohra paper. Very importantly, no serious AE has been reported in the literature since 1992, and no death possibly associated with chiropractic PMT has been reported in the literature for over 40 years. Both cases of death had descriptors of technique unfamiliar to modern PMT as noted above. However, any intervention with the potential to help has the potential to harm. For the majority of parents chiropractic care is not considered mainstream. This may bring uncertainty and concern about what the chiropractor perceives is the problem and how they will address it.

The reality of a healthcare interaction is that the perception of both doctor and patient, and those close to the patient – such as the parents – may have an impact on the outcome. The significance relates to how the child experiences pain with regard to their parent’s emotional state, and reactions to the pain-causing experience. This may be seen in practice as the effect of the parent’s attitude towards chiropractic care and/or granting a locus of control over their child to the practitioner. This has been clearly outlined in Kai’s (1996 [16]) reporting of what worries parents when their preschool child is acutely ill. Two primary issues were raised: the parental locus of control when their child was ill, and the perceived threat that the illness posed to the child. That perceived threat may increase the anxiety of the parent, which both Clinch [17] and Tsao et al. [18] demonstrated as having a direct effect on the child’s perception and outcome of a procedure. The ramifications of the parent’s frame of mind regarding their child’s health go well beyond the present health problem. Goubert et al. [19] found that parent’s catastrophic thinking about their child’s pain had a significant contribution in explaining parenting stress, parental depression and anxiety, and importantly, the child’s disability and school attendance.

The importance of the parents’ perception of their child’s pain and the procedure they are to undergo cannot be overemphasised, as a number of potentially detrimental effects flow from it. This can be harnessed positively by the chiropractor when a child presents for care. It is important the parent understands the problem, what risks and benefits are associated with varying treatments, and is given reassurance. It is important also to involve the child in the conversation, particularly if they are female. [17]

Since 1992 there has been an increase in the global population of chiropractors, the number of countries chiropractic is practiced in, the number of international chiropractic educational institutions, the publication of paediatric related chiropractic literature and CAM usage (in which chiropractic is consistently listed as one of the most common). [20, 21] A recent survey of ICPA members [22] noted 21% of average weekly visits to chiropractors were for patients less than 18 years old.

The combination of the above would suggest one of several possibilities:

The chiropractic profession may be exceedingly poor at reporting AE in the literature;

The chiropractors are not aware of the AE, and paediatric patients may be reporting to hospital or medical offices following the incident. The thorough searches conducted into the safety of paediatric chiropractic over the past 4 years [4, 6, 8] have not discovered such reporting in the literature, making this possibility less feasible.

A third and distinct possibility is that AE in the paediatric population are rare.

The chiropractic literature now has numerous publications giving clear direction for appropriate application of PMT. Pistolese [9] provides a well-written guide to approach PMT in his discussion. Vallone et al. [7] in their paper ‘First do no harm – chiropractic care and the newborn’ provide excellent background information on the newborn and the clinical approach to care. Hawk et al. [2] in their best evidence recommendations for paediatric chiropractic care suggest age appropriate techniques.

Clinical bottom line

The application of modern chiropractic paediatric care within the outlined framework [2, 6, 7, 9] is safe. A reasonable caution to the parent/guardian is that one child per 100–200 attending may have a mild AE, with irritability or soreness lasting less than 24 h, resolving without the need for additional care beyond initial chiropractic recommendations.

Appendix A: Risk assessment of neurological and/or vertebrobasilar complications

in the paediatric chiropractic patient.

In order to construct the most meaningful estimate of paediatric chiropractic visits, it was necessary to construct an estimate which covered approximately the same time span over which the literature search was conducted; i.e., between the years 1966 and first quarter of 1998. In that regard, essentially no survey data, representative of the chiropractic profession as a whole, was available between 1966 and 1977 (approximately one decade). Thus, data for this period was, for the most part, carried over from data derived from the three sources covering the period of 1978 through the first quarter of 1998. However, it was deemed appropriate to reduce category 3 (no. of active chiropractors) by 66.7%, as this change closely approximated the average increase in this category for the decade between 1978 and 1988.

Appendix B: Differing definitions of negative events associated with chiropractic care

in the recent chiropractic literature.Alcantara J. Ohm J. Kunz D.

The Safety and Effectiveness of Pediatric Chiropractic: A Survey of Chiropractors and Parents

in a Practice-based Research Network

Explore (NY) 2009 (Sep–Oct); 5 (5): 290–295

Treatment-associated aggravations: worsening of symptoms or complaints following treatment.

Treatment-complications: cerebrovascular accidents, dislocation, fracture, pneumothorax, sprains and strains, or death as a result of treatment.

Miller J.E. Benfield K.

Adverse Effects of Spinal Manipulative Therapy in Children Younger Than 3 Years:

A Retrospective Study in a Chiropractic Teaching Clinic

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2008 (Jul); 31 (6): 419–423

Mild: transient and lasting <24 h

Moderate: requiring medical (general practitioner) treatment

Severe: requiring hospital treatment

Vohra S, Johnston BC, Cramer K, Humphreys K.

Adverse Events Associated with Pediatric Spinal Manipulation: A Systematic Review

Pediatrics. 2007 (Jan); 119 (1): e275-83

Minor: self-limited, did not require additional medical care

Moderate: transient disability, involving seeking medical care but not hospitalisation.

Severe: indicating hospitalisation, permanent disability, mortality.

References:

Alcantara J, Ohm J, Kunz D.

The Safety and Effectiveness of Pediatric Chiropractic:

A Survey of Chiropractors and Parents in a Practice-based Research Network

Explore (NY) 2009 (Sep–Oct); 5 (5): 290–295Hawk C, Schneider M, Ferrance RJ, Hewitt E, Van Loon J, Tanis L.

Best Practices Recommendations for Chiropractic Care for Infants, Children,

and Adolescents: Results of a Consensus Process

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 (Oct); 32 (8): 639–647Miller JE, Benfield K.

Adverse Effects of Spinal Manipulative Therapy in Children Younger Than 3 Years:

A Retrospective Study in a Chiropractic Teaching Clinic

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2008 (Jul); 31 (6): 419–423Vohra, S, Johnston, BC, Cramer, K, and Humphreys, K.

Adverse Events Associated with Pediatric Spinal Manipulation: A Systematic Review

Pediatrics. 2007 (Jan); 119 (1): e275–e283Alcantara J.

A critical appraisal of the systematic review on adverse events associated with pediatric spinal manipulative therapy: a chiropractic perspective.

J Ped Maternal Fam Health 2010;9(March):22–9.Miller, JE.

Safety of Chiropractic Manual Therapy for Children:

How Are We Doing?

J Clinical Chiropractic Pediatrics 2009 (Dec); 10 (2): 655–660Vallone S, Fysh P, Tanis L.

First do no harm – chiropractic care and the newborn.

JCCP 2009;10(2):647–54.Humphreys, B., 2010.

Possible Adverse Events in Children Treated By Manual Therapy:

A Review

Chiropractic & Osteopathy 2010 (Jun 2); 18: 12Pistolese RA.

Risk Assessment of Neurological and/or Vertebrobasilar Complications

in the Pediatric Chiropractic Patient

J Vertebral Subluxation Research 1998; 2 (2): 73–78Zimmerman AW, Kumar AJ, Gadoth N, Hodges FJ.

Traumatic vertebrobasilar occlusive disease in childhood.

Neurology 1978;28:185–8.Shafrir Y, Kaufman BA.

Quadriplegia after chiropractic manipulation in an infant with congenital torticollis caused by a spinal cord astrocyoma.

J Pediatr 1992;120:226–9.Rageot E.

Complications and accidents in vertebral manipulation [in French].

Cah Coll Med Hop Paris 1968;9:1149–54.Terrett AGJ.

Vertebrobasilar stroke following manipulation.

NCMIC publication. Des Moines 1996.Koch LE, Koch H, Graumann-Brunt S, Stolle D, Ramirez J-M, Saternus K-S.

Heart rate changes in response to mild mechanical irritation of the high cervical spinal cord region in infants.

Forensic Science Intl 2002;128:168–76.Biedermann H.

Kinnematic imbalance due to suboccipital strain in newborns.

J Manual Medicine 1992;6:151–6.Kai J.

What worries parents when their preschool children are acutely ill, and why: a qualitative study.

BMJ 1996;313: 983–6.

Further reading

Clinch J., Dale S.

Managing childhood fever and pain –– the comfort loop.

Child Adolesc Psychiatry Mental Health (online) 2007; 1(7).

Available from http://capmh.com/content/1/1/7Tsao J, Lu Q, Myers C, Kim S, Turk N, Zeltzer L.

Parent and child anxiety sensitivity: relationship to children’s experimental pain responsivity.

J Pain 2006;7(5):319–26.Goubert L, Eccleston C, Verhoort T, Jordan A, Crombez G.

Parental catastrophizing about their child’s pain. The parent version of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS-P): a preliminary validation.

Pain 2006;123(3):254–63.Barnes PM , Bloom B , Nahin RL:

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Adults and Children:

United States, 2007

US Department of Health and Human Services,

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD, 2008.Tindle HA, Davis RB, Phillips RS, Eisenberg DM.

Trends in use of complementary and alternative medicine by US adults: 1997––2002.

Altern Ther Health Med 2005;11(1): 42–9.Alcantara J, Ohm J, Kunz D.

The Chiropractic Care of Children

J Altern Complement Med. 2010 (Jun); 16 (6): 621–626Carnes D, Mars TS, Mullinger B, Froud R, Underwood M.

Adverse Events and manula therapy: A systematic review.

Manual Therapy 2010;15:355–63.

Return to PEDIATRICS

Since 10-04-2011

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |