|

Chapter 8

Compendium of Clinical Geriatrics

From R. C. Schafer, DC, PhD, FICC's best-selling book:

“Basic Chiropractic Procedural Manual”

The following materials are provided as a service to our profession. There is no charge for individuals to copy and file these materials. However, they cannot be sold or used in any group or commercial venture without written permission from ACAPress.

All of Dr. Schafer's books are now available on CDs, with all proceeds being donated

to support chiropractic research. Please review the complete list of available books.Clinical Approach Common Neurologic Aspects of Aging Disorders Chronic Respiratory Disorders in the Elderly Common Cardiac Disorders Common Peripheral Vascular Disorders Common Hematologic Disorders Common Digestive and Gastroenterologic Disorders Common Urologic Disorders Common Dermatologic Disorders Common Endocrinologic Disorders Common Gynecologic Disorders Common Ophthalmic Disorders in Geriatrics Common Otohinolaryngologic Disorders Common Orthopedic Disorders Sexual Aspects of Aging Common Complaints and Symptoms in Later Years Common Drugs and Their Reactive Effects Professional Obligations

Chapter 8: A Compendium of Clinical Geriatrics

The objective of this chapter is to focus attention on disorders witnessed in practice by those dealing with the geriatric patient. Following neurologic disorders, heart, vascular, and blood disorders are discussed. Digestive and gastroenterologic disturbances are then followed by disorders of the urinary system, skin, endocrines, and reproductive system. Next, eye, ear, and throat conditions are followed by orthopedic and respiratory considerations. The chapter concludes with information about the sexual aspects of aging, common complaints and symptoms, and other pertinent considerations.

The topics described in this chapter are not to be considered a complete reference for all geriatric conditions seen in practice. They have been chosen as those most likely to be encountered or because they present a unique situation necessary for differentiation and/or case management.

While some described disease states may not be commonly considered within the scope of chiropractic general practice, their diagnosis is. Thus, this general knowledge will help clarify when referral should be considered, thus serving the best interests of the patient and possibly avoiding a potential accusation of professional negligence.

It is the editor's opinion that most errors in diagnosis or judgment do not occur from a lack of clinical knowledge. They occur as the result of a hurried history and examination. A clinician must be self-disciplined to give full attention to the patient at hand, without distracting concern for those patients waiting in the reception room.

CLINICAL APPROACHIn past years, it was a frequent fault of young practitioners of all disciplines to contribute age an important etiologic factor. It is emphasized that age alone is an inadequate factor in the cause of severe illness in the elderly. Careful examination, treatment of the whole individual, and prolonged follow-up is necessary for optimal results.

Most pathologists readily admit that disease is a process, not a state, but rarely is the process defined other than to say that disease of any tissue or organ is the result of disturbed function --normal physiology gone wrong.

According to most authorities, health is that condition when cells are stimulated (irritated) by nerve impulses that results in specialized cellular function to be increased or decreased so to adapt to environmental needs. While there are no new functions in disease, disease is that state where specialized functions are increased or decreased because some abnormal factor (mechanical, chemical, or psychic) is affecting the nervous system. Thus, disease is the result of abnormal or subnormal function or of normal function out of time with need. While health is the result of the organism maintaining a constant composition of the internal environment, disease results when abnormal function changes the internal environment and threatens cellular integrity.

Abnormal function is the result of perpetuated environmental, mechanical, or psychic irritation of the nervous system interfering with normal control of function for adaptation. As pain, muscle contraction, and visceral dysfunction are symptomatic of many diseases, most disease states are the result of excessive neural impulses rather than a reduction of impulses. In chronic states, for example, anoxia causes the nerve to lose its ability to transmit impulses properly. This results in analgesia, muscle flaccidity, and autonomic dysfunction.

Several pairs of nerves do not pass through movable spinal foramina and direct intervertebral pressure is not common except in severe trauma or advanced degenerative states. However, slight fixation of a vertebra producing neurologic insult can cause abnormal (mechanical, congestive, and/or metabolic) sensory irritation, motor spillover, and/or axoplasmic flow impediment. Thus, microscopic rather than macroscopic subluxation effects are more commonly witnessed clinically.

Symptoms indicate abnormal function; ie, normal function that has been increased or decreased out of time with individual needs. This function points to the organ or structure involved as well as the nerves or final common paths that would normally cause the same function when irritated by impulses initiated by normal controls.

Experience shows that manipulation, diet, counsel, physiotherapy, drugs, and surgery can relieve harmful irritation on the nervous system when used on the right patient at the right time and in the proper combination. As there are multiple causes in any disorder, no profession offers a panacea for any or all disease. The objective of any rational approach is to adjust the individual to better adapt to the environment or adjust the environment to the individual's needs if possible.

COMMON NEUROLOGIC ASPECTS OF AGING DISORDERSNormal Variations

The examining physician must hold a flexible attitude to broaden his criteria of normalcy while evaluating a senior citizen so not to confuse a disorder with a manifestation of the aging process. Aging cannot be measured by years alone; however, without a better yardstick, the following neurologic conditions are based on clinical observation of patients 65 years or over. In such observations, physical signs often offer a differentiation between organic illness and disorders within the normal limits of a particular age group.

Aging is characterized by a steady loss of neurons in the general nervous system that begins in early adulthood (about age 25). Mental disorders result such as absentmindedness, insomnia, and rigid mental attitudes. Neuron loss affecting both brain and spinal cord results in the common signs described below.Eyes. Aging eyes are characterized by arcus senilis, pupil irregularity and inequality, fading iris color (more in blue than brown), and an irregular pupillary outline. In the elderly, pupils tend to become smaller and respond less to light or dark accommodation.

Reflexes. While upper-extremity reflexes appear normal in the aged, lower extremity reflexes are characterized by reduced ankle reflexes and reduced position sense in the toes. Tendon jerks (especially the ankle reflex) may vary plus or minus in comparison to the younger person without other signs of lower motor neuron disease. However, reflex absence or reflexly induced clonus is abnormal at any age. It is debatable whether diminished ankle vibratory sensitivity is significant without further supporting tests.

Muscles. There is a general decrease in muscle bulk in the latter years, especially noted in the small muscles of the hands; and loss of muscle tone in spinal, neck, and facial areas is typical. See Figure 8.1. Muscle strength, however, usually remains intact. It is not abnormal during old age that fine finger movements become less adept. Older people generally show a definite resistance to passive movement of the limbs.Cervical spondylosis is commonly seen, and it may accentuate upper-extremity muscle degeneration. Peripheral vascular occlusion affecting the vasa vasorum may be evident. Loss of neurons from the anterior horn cell pool often give rise to clinically recognizable neurologic signs in 50%--80% of patients over age 70.

Infections

Three infections are of primary concern in geriatric neurologic disorders: zoster infection, meningitis, and syphilis.Zoster Infection. In aging, normal resistance to the herpes zoster virus is lowered. While cervical, thoracic, and lumbar types occur frequently, infection of the facial and cranial types predominate.

Geniculate zoster is characterized by vesicular formation on the exterior ear, soft palate, internal cheek, or along the jaw, with loss of taste on the affected side. Severe pain is noted, beginning in the ear and progressing to the throat and down the neck. The classic complication is severe peripheral ipsilateral facial palsy with denervation.

Ophthalmic zoster features severe pain, redness and swelling of the forehead and cheek around one eye, marked eyelid edema, and neuropathic keratitis. Later stages feature a vesicular rash that becomes purulent in the area supplied by the trigeminal nerve, along with increasing pain, fever, leukocytosis, and sometimes ipsilateral oculomotor paralysis.

Meningitis. Pyogenic meningitis is one of the most silent neurologic abnormalities witnessed in geriatrics and is often misdiagnosed. It's characterized by headache, disorientation to time and place, insomnia, fatigue, demotivation, and slight pyrexia. Although rarely a patient complaint, palpation of the cervical muscles will reveal spasm affecting flexion but not rotation. In later stages, characteristic signs are vomiting with dehydration, increased mental confusion, disorientation, dementia, stupor or coma, and leukocytosis. Meningitis is more common in the elderly than meningism.

Syphilis. Geriatric characteristics of syphilis include dementia paralytica, decreased pupil reflex and extensor plantar reflexes, tremors particularly of the tongue and extremities, slurred speech, depression, and progressive delusionary dementia.

Trauma

With increased forgetfulness and decreased proprioception, the elderly tend to trip and fall more often. Frequently misdiagnosed subdural hematoma is characterized by a history of head injury followed by varying degrees of dizziness, and hemiparesis or hemiparesthesia with Jacksonian convulsions. Headache is not always present. Personality signs may include confusion, forgetfulness, loss of judgment, and other personality changes, which may be attributed in error to senile dementia. Often a differential diagnosis cannot be made without electroencephalography, cerebrospinal fluid examination, and/or carotid angiography.

Extradural hematoma is less common and characterized in the elderly by convulsions, hemiplegia, coma, and rapid progress downward. Parietal fracture is often associated. Following severe head injury, intracerebral hematoma not part of cerebrovascular disease may be witnessed. Signs include papilledema, bradycardia, progressing stupor, and hemiplegia.

Neoplasms and Brain Tumors

No age group is exempt from benign new growths; however, primary and secondary malignancies tend to have a slower growth rate in the elderly. Convulsions without a history of cerebral infarction are more likely the effect of cerebral tumor than of uremia, hypertension, or cerebrovascular disease. In the later stages, papilledema, headache, vomiting, and blurred vision manifest. Peripheral musculature degeneration is accompanied by loss of supinator and ankle reflexes, with sensory loss following in the hands and feet.

While brain tumor is infrequently witnessed in the geriatric population, the physician must be on guard against its occurrence as well as chronic subdural hematoma, which may closely simulate cerebral tumor in signs and symptoms. The characteristic syndromes of brain tumor are the result of the tumor growing and consuming space such as with symptoms of papilledema, headache, stupor, vomiting, and especially a progressive neurologic deficit. An expanding mass may be suspected with progressive sensory loss, ataxia, poor coordination, paralysis, visual impairment, neural deafness, aphasia, and convulsions.

Tumors within the central nervous system arise as meningeal, supratentorial, or infratentorial in origin. Signs may appear slowly or abruptly. Abrupt and dramatic occurrence is more suggestive of metastatic lesions.

Meningeal signs. Severe headache is the rule. Pain is diffuse and unremitting in both sarcoma or carcinoma. Because of nuchal rigidity, headache develops before any other neurologic sign.

Supratentorial signs. In the early stages, specific signs are sensory disturbances, paresis, apraxia, convulsions, and seizures. General signs include fatigue, general weakness, and emotional and behavioral changes. In the late stages, vomiting, headache, and mental dullness often develop.

Infratentorial signs. Early signs offer local syndromes of cranial nerve dysfunction, imbalance, intracranial pressure effects, and limb ataxia. In late stages, focal or lateral paresis or sensory signs may develop.

Cranial x-ray films may show a significant shift of a calcified pineal gland from its normal midline position as well as pressure demineralization of the dorsum sellae. Meningiomas, oligodendrogliomas, and other slow-growing tumors may contain x-ray opaque patches of calcification.

Stroke and Vascular Diseases

A stroke may be defined as an abruptly developing neurologic abnormality secondary to an occlusive or hemorrhagic vascular accident of brain vessels. Stroke is the second leading cause of death in persons over 75 years. On suspicion of a cerebrovascular attack after initial observation and history, the examining physician must determine whether the "accident" is in the anterior (carotid) or posterior (vertebrobasilar) arterial circulation.

Features of Anterior Arterial Stroke. The characteristic syndrome includes contralateral weakness or numbness, transient ipsilateral monocular blindness with homonymous visual field defects, ipsilateral throbbing headache, mental confusion, dysphasia, and apraxia with dominant hemisphere involvement.

Features of Posterior Arterial Stroke. The syndrome of vertebrobasilar artery disease includes dysarthria and dysphagia; unilateral or bilateral motor or sensory deficits, often associated with cranial nerve involvement; visual field defects; vertigo; tinnitus; deafness; and generalized imbalance with unilateral limb paralysis. These signs tend to be bilateral or generalized.

Within the aged, most neurologic syndromes are manifestations of vascular disease. Such disorders range from a minor syncope to a complicated stroke. By far, occlusive cerebrovascular disease is the most common etiology. Ten commonly witnessed clinical conditions are listed below along with their major characteristics.

Minor stroke. Mild stroke is a neurologic deficit due to cerebrovascular disease that lasts more than 1 day followed by almost complete recovery within a few weeks. The effects are probably from ischemic necrosis with minimal infarction. Minor strokes often prelude major strokes within 1 or 2 years in 50% of patients. In short stenotic lesions of the internal carotid artery, a fairly high-pitched pansystolic murmur over the artery on the opposite side of the neurologic deficit can be heard in 50% of the patients. In subclavian artery occlusion, the ipsilateral arm supplied by a reversed flow in the vertebral artery leads to hindbrain arterial insufficiency when the arm is used strenuously.

Major stroke. Severe stroke is characterized by considerable neurologic deficits developing several weeks after the attack. Signs include mental disturbances such as poor comprehension, memory loss, demotivation, lack of perseverance, apathy, and slowed mental faculties. The immediate principles of treatment include maintenance of free airways, preservation of systemic circulation, adequate hydration and nutrition, and prevention of secondary respiratory and urinary infection, urine retention, and pressure sores.

Transient ischemia attacks (TIAs). The underlying cause of cerebral TIAs appears to be occlusive cerebrovascular disease with either intracranial or extracranial arterial atherosclerosis. They are often complicated by atheromatous ulceration of the intima. Attacks last from minutes to hours followed by complete recovery within 24 hours and feature transient attacks of hemiparesis, hemianesthesia, hemianopia, aphasia, and/or loss of vision in one eye if the disorder occurs in the territory of the carotid artery.

Signs of vertigo, dysphagia, dysarthria, blurred vision and diplopia, and vomiting suggest hindbrain ischemia in the territory of the vertebral artery. See Figure 8.2. Transient attacks can be the result of microemboli (platelet, cholesterol, fibrin) carried to the cerebral arteries; systemic hypotension; or atheromatous occlusion of the major arteries of the neck with diminished blood flow associated with local stenosis. Hindbrain ischemia is more common when hypotension is the cause. The carotid variety is more frequently associated with a distal embolism from local atheroma and hypertension.

If the hemoglobin percentage is below normal, strenuous exertion can produce signs of cerebral ischemia. In cervical spondylosis combined with degenerative arterial disease, cervical postures requiring extension and full rotation of the head can interfere with vertebral artery blood flow. Because of its vasoconstrictive effects, heavy smoking may cause ischemic attacks. Hypotensive acting drugs may be iatrogenic etiologies.

In hindbrain ischemia, falling attacks are part of the syndrome. Patients may suddenly lose all postural tone and fall heavily to their knees or face without losing consciousness. Patient anxiety, thus, increases. The accident is often misinterpreted as a "misstep" by the patient.Vertigo. Dizziness, unsteadiness, and loss of equilibrium may result on arising from a recumbent to a sitting posture or from a sitting to a standing posture, The cause is usually physiologic, resulting in diminished cerebral blood flow. Such syncope may result in injury.

Syncopal attacks. These attacks may or may not be associated with occlusive vascular disease. The cause can often be traced to failure of baroreceptor mechanisms in the neck or to changes in systemic arterial circulation. In the elderly, attacks are frequently called micturition syncope when an elderly patient arises quickly from bed to enter the bathroom and suffers an attack of syncope.

Cough syncope. This disorder is characterized by a sudden loss of consciousness, often prolonged, from a heart block producing a Stokes-Adams attack in emphysematous and bronchitic patients. The pulse is usually 40 per minute or below, and electrocardiography usually shows evidence of complete atrioventricular dissociation.

Hypertensive encephalopathy. This disorder features focal or generalized fits, headache, blurred vision, hemiparesis, and a diastolic pressure over 140. Along with these signs, diagnosis can be made from fundi observation where retinal hemorrhages and exudates with papilledema exist.

Cranial arteritis. If left undiagnosed and untreated, this geriatric disorder can result in half the affected elderly patients becoming permanently blind. The disorder is characterized by severe persistent headaches, often temporal and unilateral, with dim or loss of visual acuity, Associated pain in the shoulders and hips is reported if the arteritis is widespread. The condition is often called giant-cell arteritis or temporal arteritis because of the local manifestation, and the most damaging retinal involvement is frequently overlooked.

The temporal arteries are normally tender and sometimes lose their pulsation. They frequently protrude during an attack as thickened cords under hot red overlying skin. Fundi examination shows retinal hemorrhage or some degree of optic atrophy or thrombosis of the retinal artery in 50% of the patients. Abnormalities may be bilateral. Other signs may include a mild fever, leukocytosis, occasional eosinophilia, and a raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate.Apoplexy. This is a less common type of stroke in the elderly and associated with hypertension, probably the effect of rupture of one or more microaneurysms in the smaller branches of the middle cerebral artery. Hemorrhage into the lateral ventricle or subarachnoid space results in complaints of headache and vomiting. Rapid unconsciousness occurs, progressing to deep coma. Flaccid muscles are noted in the face and limbs on the hemiplegic side. The eyes turn first toward the affected limbs conjugately and then away from the affected limbs.

While uncommon in the elderly, primary intracerebral hematoma may occur if the bleeding is confined. In such a case, it is almost impossible to differentiate the condition from cerebral infarction.Primary subarachnoid hemorrhage. Although commonly thought of as a young person's disorder, it is not uncommon for a congenital cerebral aneurysm to rupture during the senior years. In the elderly, headache and neck stiffness may not be severe. However, coma is usually sudden and prolonged, and gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea may be predominant in a stuporous patient. Recuperation is extremely slow in the elderly. Communicating hydrocephalus may arise because of the occlusion of the arachnoid villi. If this occurs, severe dementia results.

Common Deficiency States

As will be detailed in the next chapter, deficiency states often result from a decrease in appetite, improper food processing, and improper intake combined with poor absorption and slow metabolism, producing conditions unfavorable for normal function of the nervous system.Cyanocobalamin Deficiency. Classical B-12 deficiency results in subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord. Neurologically, the condition begins as a symmetric neuropathy with characteristic absent reflexes and peripheral sensory loss, particularly of the vibration sense and position proprioception. Ankles become weak, hands and feet become clumsy, tingling in fingers and toes are noted, and it is difficult for the patient to feel the ground beneath the feet. There may be evidence of pernicious anemia, tongue atrophy, megaloblastic bone marrow, and low serum cyanocobalamin. Achlorhydria is almost always complete. Mental signs include forgetfulness, disorientation, increasing dementia, and psychotic states. Primary optic atrophy is commonly associated in elderly cigarette smokers.

Thiamine Deficiency. Classic B-1 deficiency is commonly the result of alcoholism, producing myelopathy, encephalopathy, and neuropathy. The sensory-motor type neuropathy is characterized by peripheral muscle weakness and degeneration, pain in the lower extremities, and paresthesias in the hands. Severe chronic deficiency often accompanied by heart failure and cardiomyopathy (wet beriberi). Some neurologic changes may be permanent such as amnesia, disorientation, areflexia, and muscle tenderness. Basic treatment consists of supplemental B-complex plus vitamin C, increased carbohydrates, and restricted alcohol despite type.

One related encephalopathy shows itself as Korsakoff's psychosis with associated confabulation, amnesia of recent events, and disorientation of person, place, or time. Another type known as Wernicke's encephalopathy is characterized by ataxia, tremor, nystagmus, pupillary abnormalities, ocular nerve paralysis, and stupor sometimes progressing to coma. The onset is often sudden and may be confused with intracranial tumor, virus encephalitis, or meningitis.

Note: Deficiency of other vitamins in the B group can produce acute mental and emotional disorders in the elderly suffering from malnourishment. States of confusion are common, especially in riboflavin and nicotinic acid deficiency. Differential diagnosis is made by finding fissures at the corners of the mouth, pigmentation over pressure areas, and a raw red tongue.

Common Metabolic DisordersHypothyroidism. Coma due to hypothermia can be a neurologic manifestation in the elderly. Other clinical features include deafness from auditory nerve degeneration, peripheral neuropathy, and cerebellar ataxia. With hypothyroidism, cerebellar disturbance resulting in loss of balance, giddiness, unsteadiness, and motor clumsiness may be the syndrome. This is accompanied by obesity, sluggish mentality, deafness, lowered voice tone, and bradycardia with its associated symptoms. Tendon reflexes indicate a slow phase of relaxation. Associated carpal tunnel syndrome points to peripheral neuropathy but is more common in the middle-aged than the geriatric patient. Diagnosis is confirmed biochemically with blood protein-bound iodine below 3 mg/100 ml and the serum cholesterol content about 300 mg/100 ml.

Diabetes Mellitus. In the elderly, diabetes is the most significant disorder producing metabolic neurologic diseases. It may present a neurologic picture of mild peripheral neuropathy with absent tendon reflexes, peripheral sensory loss, impaired peripheral circulation, muscle degeneration, and a flapping-type gait. In diabetic amyotrophy, proximal weakness and wasting of the lower extremities may be evident. A 5-hour glucose tolerance curve is necessary because of the mildness of the diabetes. In geriatrics, hypoglycemia may be the manifestation of either insulin therapy or an islet-cell tumor causing an intrinsic overproduction of insulin. The condition is characterized by sudden fainting attacks, hemiplegia, convulsions, and irrational behavior.

Drug Reactions. As chiropractic patients may also be under medical care, it is well that the doctor of chiropractic can recognize drug reactions in the elderly, particularly reactions from common hypotensives and sedatives. If hypotensives are prescribed, reactions may include convulsive or syncopal attacks.

It is always advisable to inquire about medical therapy before diagnosing systemic disorders. Barbiturates produce some of the most usually encountered neurologic drug reactions in geriatrics, producing cerebellar ataxia, dysarthria, nystagmus, mental incoordination, dizziness on looking upward, manual incoordination, staggering gait, loss of balance, and altered behavior. Barbiturates in combination with alcohol can produce the grossest abnormalities of mental and physical control. Drug reactions will be described further in the final section of this chapter.

Carcinomatous Neuropathy. While less common in senior citizens, bronchial carcinoma is one of the most common causes of peripheral neuropathy. Thus, neuropathy of unknown origin should be checked by a chest film. Such a neuropathy may be either a motor, sensory, or motor-sensory type.

Neurologic Disorders of Unknown EtiologyParkinsonism. This syndrome is characterized by ideas of persecution, depression, aggressive behavior, disorientation, frightening hallucinations, and behavior disorders difficult to control (especially in patients with concomitant generalized cerebral ischemia). Cerebral infarction is often misdiagnosed as arteriosclerotic parkinsonism. While cerebral infarction may exhibit generalized rigidity, difficulty in initiating voluntary movements, and even parkinsonian facies, it is extremely rare for extrapyramidal tremor to develop because of atherosclerosis. Studies offer evidence that parkinsonism is due to a deficiency of dopamine in the extrapyramidal system.

Senile Tremor. True senile tremor does not affect the hands as much as the head and tongue. Here, head nodding is conspicuous and advances with age. Differentiation from parkinsonism is needed. Pseudosenile tremor is an exaggeration of a familial tremor that worsens with age. The hands are affected first, then symptoms progress to the head and finally to the tongue. It is an intention tremor worsened by social stress. Ethanol is a palliative, and undisciplined use may lead to alcoholism.

Myasthenia Gravis. While the classic form of this disease, with its peripheral or ocular weakness that increases as the day progresses, is more common in young patients, elderly patients more often exhibit the bulbar type characterized by loss of voice after speaking for a few minutes. Chewing and swallowing become a chore. Ptosis without diplopia is evident. In the late stages, respiratory muscles become involved.

Trigeminal Neuralgia. Tic douloureux, commonly seen in the elderly, is characterized by sudden lancinating pain paroxysms in the face unilaterally on sensory stimulation such as by eating, talking, washing, or rubbing the face. Severe pain and muscle spasms of the face are characteristic.

Clonic Facial Spasm. The clinical picture of this disorder is an effect of degenerative changes in the facial nerve nucleus, seen unilaterally, and beginning as an eyelid tic. More commonly seen in women than men, the tic spreads to the whole side of the face, increases in severity, and results in the angle of the mouth being drawn upward and the eyelid completely closed.

Motor Neuron Disease. The peripheral form is progressive, bilateral, shows increased tendon reflexes without sensation alteration, and features muscle atrophy affecting the hands, arms, and shoulder girdle with evidence of fasciculation and muscle degeneration. It is more benign than the medullary form, which is usually severe and characterized by tongue atrophy, rapidly progressing dysphagia, dysarthria, and respiratory failure. Prognosis seldom exceeds 1 year for the medullary variety.

Neurologic Disorders from Skeletal Changes

Senior citizens are the most likely age group to present with skeletal abnormalities. See Figure 8.3. Cervical spondylosis, Paget's disease of bone, and osteoporosis are the three main conditions seen clinically.Cervical Spondylosis. While spondylosis is commonly demonstrated by x-ray films of the elderly, neurologic effects may not be evident. Osteophytes may distort the vertebral arteries and affect hindbrain circulation --resulting in cerebral ischemic attacks, particularly during cervical extension and rotation. A murmur may be heard over the artery in the supraclavicular fossa. Also, ischemic myelopathy may be the result of transverse intervertebral bars that interfere with the blood supply to the cervical cord. This situation is characterized by clumsiness, weakness in the lower extremities, urinary sphincter disturbances, spastic lower limb muscles with exaggerated tendon reflexes, clonus and extensor plantar responses, restricted neck movements, paresthesias in the hands, and upper-extremity sensory loss of peripheral and occasionally segmental distribution. The posterior columns may become involved by cord compression.

By increasing cord circulation and reducing cord pressure, upper limb pain diminishes, lower limbs tend to relax, nocturnal flexor spasms decrease, and extensor plantar responses can change to flexor responses. In the elderly, cervical traction is usually contraindicated as it might increase attacks of hindbrain ischemia. Differential diagnosis should consider subacute combined cord degeneration, cord tumor, and atherosclerotic myelomalacia.

Paget's Disease of Bone. This disorder is characterized by symmetrical facial weakness, headache, lower extremity pain, and deafness, and it occasionally results in cord compression. Determination is made by hearing a murmur over affected bones and finding a raised alkaline phosphatase level, typical radiologic findings, and the often concomitant high-output cardiac failure.

Osteoporosis. In geriatrics, this condition is characterized by spinal pain and occasional root pain as the effect on the spinal column produces neurologic symptoms. Serum calcium and phosphorus usually appear normal. Diagnosis is confirmed by roentgenography, which allows differentiation from secondary deposits or myelomatosis, evidence of a primary growth with localized osteoporosis, or osteosclerosis in carcinoma. Myelomatosis is differentiated by serum protein changes and a high sedimentation rate. In cord or cauda equina compression, vertebral collapse is rarely the cause. Overmedication for thyrotoxicosis or of corticosteroids should be considered if the patient has been or is under medical care. Besides regular chiropractic care, concern should be given to maintaining a positive nitrogen balance that is important for calcium retention, to bed rest, and to nonweight-bearing exercises until the patient is ambulatory.

Senile Dementia This vaguely defined disorder is difficult to set apart from the normal aging process and all too often the diagnosis is the result of elimination of more specific disease processes. Rather than a disease process, senile dementia is looked on as an incremental deterioration of the nervous system contributed to by vascular and metabolic deficiencies, progressive sensory insufficiency, and/or social and cultural isolation.Simple Dementia. This disorder is characterized by diminished recent recall and memory, shortened attention span, increased task performance time, and difficulty in orienting to new situations and chores.

Senile Psychoses and Degenerative Dementia. The degenerative dementias are clinically marked from simple dementia by distinct pathologic features. Disorientation, delusions, and hallucinations advance from simple confusion. Aphasia, apraxia, or agnosia may appear, making speech and gestures inappropriate. Hemiparesis and epileptic or spontaneous choreiform movements may precede complete helplessness or coma.

Differentiation should be made from associated or underlying metabolic or toxic psychoses. Subacute spongiform encephalopathies have distinguishable pathologic features. Frontal fossa meningioma, incisural block, or chronic subdural hematoma may be responsible for a deteriorating mental state, as would disorders such as uremia; diabetes mellitus; myxedema; pulmonary, hepatic, or renal insufficiencies and encephalopathies; CNS syphilis; or congestive heart failure. Localized cerebrovascular disease, schizophrenia, and Wernicke and Korsakoff syndromes should be ruled out, and the presence of Alzheimer's disease, arteriosclerosis, parkinsonism dementia, or Pick's lobar atrophy must be considered.

Concluding Remarks

Geriatric neurologic conditions are rarely unique to old age. No neurologic disorder can be relegated exclusively to the aged. The most common cause of neuropathy in the elderly is diabetes mellitus. The second most common cause is nutritional deficiencies associated with alcoholism and chronic illness.The Central Nervous System. Because the CNS is largely encased in bone, except for the optic nerve head, direct examination must be replaced by indirect methods that evaluate sensibility, muscle strength, coordination, gait, and station. This often requires active patient participation. Besides a regular clinical physical examination including orthopedic and neurologic tests, the chiropractic physician should listen over the cranium or blood vessels to detect bruits. Muscles should be palpated to evaluate mass and tone, and the general body surface should be examined for specific local departures from normal bilateral muscular symmetry.

Muscle Weakness. Complaints of weakness are common in senior citizens. They may stem from increased joint stiffness associated with arthritis or from muscle atrophy consequent to motor neuron disorders or disorders of muscle fiber. A simple lack of exercise should not be overlooked.

Complaints may also stem from anemia, diabetes, or pulmonary, cardiac, or systemic conditions. Disabling weakness may he the result of neuropathy, myasthenia gravis, primary myopathy, thyroid disorders, hypokalemia, hypercalcemia, sodium depletion, or hormonal or electrolytic disturbances such as seen in Cushing's disease. The occurrence of myopathy in the senior citizen is typically associated with systemic malignancy or connective tissue disorders.

Muscle weakness may be the result of local motor-nerve impulse conduction (as in an extremity) or to involvement of motor paths descending from the brain. As in stroke, an abrupt unilateral paralysis may result because of involvement of the long tracts of the CNS. Remember that a crossing of motor outflow paths from the cerebral hemisphere to the opposite spinal outflow mechanism is necessary because one side of the body is controlled by the opposite half of the brain. Similarly, sensory flow over afferent nerves eventually meets with sensory long tracts that decussate within the spinal cord in their course to the opposite cerebral cortex.

Peripheral Nervous System. Peripheral sensory impairment generally occurs in the supply of specific spinal roots, nerves, or a nerve plexus. Sensory impairment is characterized by specific patterns in nerve or root involvement. Local nerve involvement or a spinal segment disorder exhibits as muscle atrophy and flaccid paralysis. Absent tendon reflexes may show involvement of the sensory side, the motor side, or both sides of the reflex arc. While nerve or nerve root disturbances result in unilateral signs, spinal segment disturbances frequently cause bilateral signs. Any disturbance with pyramidal tract function (from cerebral cortex through the cord) will be revealed by the presence of an extensor plantar Babinski response.

The Neuropathies. Peripheral neuritis is a frequent complication in a long list of geriatric illnesses. It is extremely important clinically as it is often the earliest and only indication of systemic disease. Mononeuropathy, affliction of a single nerve, may occur temporarily and spatially among several nerves as in polyneuropathy or mononeuritis multiplex, or involve only the distal portion of nerves bilaterally as in symmetrical distal polyneuropathy. The most common mononeuropathies in senior citizens are Bell's palsy, trigeminal neuralgia, and postherpetic neuralgia.

Whether the peripheral neuritis is described as motor, sensory, or mixed, diagnosis requires two or more of the following signs:

Pain

Sensory impairment

Paresthesias

Regional muscle weakness

Projected sensations on percussion of an affected nerve

Atrophic changes in the skin and nails resulting from coincident postganglionic sympathetic axon involvement.

The Myopathies. Geriatric myopathies are usually secondary to generalized systemic disease, occurring far less than the neuropathies. The trunk, shoulder girdle, and throat areas tend to be more involved than the face, distal extremities, or diaphragm. Specific muscles or groups appear to be involved with out regard to motor nerve supply. While distal limb weakness is a feature of generalized neuropathic processes, the proximal distribution of weakness is characteristic in myopathy.

The syndromes of myopathy present with a gradually progressive course of weakness, weight loss, and reduced muscle bulk in a prolonged period. Muscles become painful on exercise. On palpation, the involved muscles are tender and "doughy" to the touch. Myotatic reflexes elicited by muscle stretch may be well preserved until severe muscle atrophy sets in during the late stages. No objective sensory signs are present.

Movement Disorders. Several neurologic conditions associated with aging are characterized by involuntary and abnormal movements of the body. Many of these are likely related to the loss of basal ganglia control. Movement disorders include the slow writhing sinuous movements of athetosis, the coarse rhythmic tremor of parkinsonism, and the brief dancing and jerky movements of chorea in the trunk and extremities (rarely the result of cerebrovascular disease in the elderly). Other movements include the stereotyped activity patterns mimicking natural behavior as seen in habit tics; the uncontrolled gestures preceding movement as seen in action dystonia; and the involuntary asynchronous and arrhythmic forced blinking, wrinkling of the nose, licking movements of the tongue, and pursing of the lips as seen in Meigs' syndrome.

The movement disorder of Parkinson's disease is commonly encountered in geriatrics. Idiopathic parkinsonism exhibits diminishing voluntary movements and progressing rigidity of the muscles of the trunk and extremities. Trunk and neck flexion is severe. The face becomes as expressionless as a frozen mask; speech is muffled with monotonous whispers; and eye motion becomes markedly circumscribed. Rapid, rhythmic tremors occur involuntarily in the head, feet, fingers, and lips that disappear briefly during volitional movement. In the more rare variety of postencephalitic parkinsonism, signs of torsion dystonic posturing, respiratory dysrhythmias, oculogyric crises, and personality and sleep disorders are seen besides the signs of idiopathic parkinsonism.

As well as basal ganglia dysfunctions, disorders of the cerebellum are important considerations in the incidence of geriatric movement ailments. Cerebellar movement disorders in the aged usually manifest as either truncal ataxia with a broad based unsteady gait or as an uncoordinated action tremor in one or more limbs. Eye movements may become jerky, and speech can become slurred as in cerebellar dysarthria. Malignant metastasis can result in a subacute cerebellar syndrome when the posterior fossa is involved or result in parenchymatous degeneration of the cerebral cortex. On the other hand, fulminating cerebellar syndromes in senior citizens are frequently attributed to vertebral basilar arterial ischemia, which is often complicated by sensory and motor dysfunctions of the lower cranial nerve centers.

In evaluating any movement disorder, thyroid conditions should always be considered. Drug intoxication from tranquilizers, hypnotics, and sedatives is not beyond question. These two factors are often overlooked in the working diagnosis.

CHRONIC RESPIRATORY DISORDERS IN THE ELDERLYWhile pulmonary tuberculosis remains the most serious chronic infectious disorder of adult Americans, chronic airway obstruction disorders have replaced tuberculosis as the major concern.

Emphysema

Emphysema is increasing in incidence in the elderly. It results from loss of alveolar walls and manifests as chronic dyspnea or exertion, profound respiratory drive, and increased volume of ventilation per minute. Distribution between ventilation and perfusion is usually well maintained, thus excessive right-to-left shunting is minimized. Hypoxemia and carbon dioxide retention are rarely a factor, but chronic bronchitis may exist. Differentiation is necessary from pulmonary fibrosis and bronchiectasis.

Chronic Bronchitis

This chronic airway obstruction is characterized by chronic cough, excessive nonseasonal expectoration, dyspnea, mucous gland hyperplasia, hypoxemia, and carbon dioxide retention in established cases. Because of air trapping, the residual air volume is increased, but the total lung capacity is not. Respiratory drive is reduced, and there is altered distribution between ventilation and perfusion due to localized airway plugging and shunting through areas of reduced ventilation. See Figure 8.4 for major structures.

Differentiation must be made from neoplasm or pulmonary tuberculosis. Reactive pulmonary hypertension, cor pulmonale, or congestive heart failure may be associated. The hypoxemia may lead to secondary polycythemia. If acute bronchiolitis coexists, marked inflammation, edema, and increased airway plugging will be found.

Other Airway Obstructive Diseases

Pulmonary tuberculosis, chronic bronchial asthma, interstitial fibrosis, and chronic pneumonitis are other conditions of geriatric concern.

Pulmonary tuberculosis is rapidly becoming a disease of the elderly. On examination, lower lobe infiltrates and plural effusion may be manifestations of tuberculosis in the elderly rather than the classic x-ray findings of apical cavitation. Chronic bronchial asthma often coexists with chronic airway obstruction, as do interstitial fibrosis and chronic pneumonitis. Diffuse interstitial fibrosis is usually associated in the senior citizen with collagen disease, fibrosing alveolitis, or desquamative interstitial pneumonitis. Bronchiectasis is an infrequent finding.

COMMON CARDIAC DISORDERSPathology

In general, the cardiovascular conditions most commonly seen in geriatrics are coronary sclerosis, aortic sclerosis, and vascular nephritis. Cardiovascular deaths amount to 72% of deaths of those aged 65 years or over. A review of common pathologic changes helps to visualize what is occurring in many geriatric patients with abnormal cardiovascular signs.

In the elderly, the heart (Fig. 8.5) exhibits a general decrease in muscle cell size, smaller output, and progressively decreasing strength. Diastolic filling resistance increases, recovery of contractile ability is delayed, and there appears to be a decreased efficiency in converting nutrients into mechanical heart energy. At the cellular level, pigment increases at the poles of the nuclei, brown atrophy appears, and muscle cell striation around the nuclei decreases. Mitochondria atrophy occurs, enzymes needed for contraction reduce, and catecholamine mobilization becomes less effective, which impairs the speed and power of contraction under stress. Cardiac filling and emptying become difficult with decreased aortic elasticity and atrial atrophy. See Figure 8.6.

Because of general body atrophy, lowered BMR, and reduced work load, the normal aged heart provides an adequate output under ordinary conditions. However, the ability to compensate under stress is greatly hindered. Acute coronary insufficiency, congestive heart failure, myocardial necrosis, and arrhythmias may be the result of chronic or sudden cardiac stress, decreased venous return on standing, a sudden heart rate increase, anoxia from bleeding, hyperthyroidism, or an excess of parenteral fluids, steroids, or vasopressors. Oxygen uptake values are reduced, and the incidence of ischemic electrocardiographic S-T depressions increases with advancing years.

Diagnosis

Techniques do not vary greatly from those used in younger patients except that special care must be taken not to tire a patient with too prolonged testing during one visit. The history should include personal and familial dates, past and present; habits of diet, exercise, avocations and vocations, physical and mental occupations, and the use of drugs. Physical examination should include all systems. Laboratory tests such as urinalysis, blood profiles, electrocardiogram, and chest films are usually routine, along with special tests and views as indicated. As both cardiospasm and angina pectoris are common in the elderly, special concern must be given to differentiation. For example, dyspnea resulting from pulmonary emphysema is frequently confused with that associated with coronary heart disease because of coincidental electrocardiogram findings. Thrombosis from a leg vein can result in pulmonary embolism and be confused with acute myocardial infarction or hypostatic pneumonia because of similar symptoms and electrocardiographic findings. It is important in geriatric evaluation to realize that acute conditions are often superimposed on chronic disorders.

Prognosis

Benign arrhythmia, premature beats, and short paroxysms of atrial tachycardia tend to increase with age but are seldom important clinically.

However, special attention should be given to the presence of flutter and fibrillation, or ventricular or atrial paroxysmal tachycardias that present in prolonged episodes. Both bundle branch and atrioventricular heart block are usually the result of coronary atherosclerosis. Atrioventricular block with Stokes-Adams attacks of syncope are highly serious, even if convulsions are not present, and signals specialized care.

Rest and a simple diet are important adjuncts in congestive heart failure. In angina pectoris, walking is an excellent exercise; however, physical exertion combined with emotional stress (especially after eating or during exposure to cold and wind) should be avoided. Physical and emotional overstress should be avoided if the patient has angina attacks at rest (angina decubitus).

As no two patients are exactly alike, each must be evaluated for individual treatment or referral. Referral should not automatically imply dismissal. The ideal situation in many cases is combined cardiologist and chiropractic case management.

Prevention

While each case must be considered from an individual standpoint in the light of clinical judgment, general preventive measures should include structural and neurologic considerations, rest and exercise, nutrition and supplementation, and all the other factors necessary to aid the patient in adjusting to the environment or adjusting the environment to the patient's needs.

Rehabilitation

In reference to rehabilitation, Dr. Paul Dudley White stated: "Such rehabilitation has been accomplished by the growing recognition of nature's own curative measures that are achieved in the main through the development of collateral circulation, as well as by active measures ...."

Cardiac Ischemia

Cardiac ischemia as the result of coronary artery disease increases in severity with aging and exists in almost all individuals over the age of 70. While myocardial infarction, acute coronary insufficiency, subendocardial infarction, and the anginal syndrome are specific entities, many clinical pictures do not offer clearly defined categories. However, for the sake of classification, several disorders are described below that are commonly witnessed in geriatrics.Acute Myocardial Infarction. This disorder is frequently misdiagnosed as pneumonia or hypertensive heart disease in the elderly. It is commonly the result of fresh thrombotic occlusions producing large infarcts or less common mural thrombi. Symptoms may or may not include precordial pain, nausea, vertigo, dizziness, or epigastric discomfort. An acute attack may be superimposed on old myocardial infarctions, coronary artery disease, left ventricular hypertrophy, angina, and/or congestive heart failure. A history of definitely abnormal electrocardiograms will be found in over 60% of the cases.

In typical situations, precordial, neck, shoulder, arm, or epigastric pain occurs. Such cases usually have a low incidence of preceding failure, coronary heart disease, cardiac enlargement, or other disorders considered associated with poor collateral circulation.

In atypical (silent) myocardial infarction, the major characteristic is the lack of pain with dyspnea, dizziness, weakness, abdominal distress, or syncope. This variety is more common in patients in their 80s than in their 70s. Preceding failure, coronary heart disease, cardiac enlargement, or other disorders associated with poor collateral circulation are typical. The symptomatic picture can often be traced to functional disorders.

Dyspnea is usually attributable to acute failure of the left ventricle. Vertigo, dizziness, weakness, and mental confusion are the result of decreased cardiac output aggravated by a sluggish carotid sinus reflex and cerebral arterial narrowing affecting cerebral arterial circulation. While syncope is the effect of complete heart block with bradycardia, discomfort in the abdominal area is attributable to right cardiac failure resulting in visceral congestion. Evidence of myocardial infarction may be present without any overt subjective complaints or clinical manifestations.

The subendocardium area of the myocardium is highly susceptible to anoxia and resulting necrosis. Such a disorder occurs with anemia, fever, electrolyte depletion, hemorrhage, dehydration, and sudden hypotension. This condition is seen frequently in patients suffering with severe coronary artery narrowing. During infarction, the inner wall of the left ventricle and the septum may be totally involved.

The Anginal Syndrome. This syndrome is one of transitory coronary insufficiency seen in people with diffuse coronary artery disease. Symptoms vary considerably and overlying chronic disorders of the stomach, esophagus, lungs, and chest wall often confuse accurate diagnosis. While chest pain is typical, silent coronary artery disease is not rare. Hyperthyroidism, anemia, and the tachycardias and arrhythmias may be aggravating factors. Several episodes over several years result in multiple areas of myocardial necrosis and fibrosis, which predispose diffuse myocardial fibrosis, muscle weakness, and congestive heart failure.

Acute Coronary Insufficiency. Acute coronary insufficiency is the anginal syndrome in the extreme. If the initiating stress is greater or the arterial narrowing is more severe, the myocardial damage is greater. The precordial pain is of much longer duration. Associated findings include leukocytosis, elevated sedimentation rate, slight elevation of isoenzymes, low-grade fever, and electrocardiographic evidence of sagging or horizontal S-T depressions and T-wave inversions from several days to several weeks or even longer, with signs of chronic insufficiency progressing to a symmetric T-wave inversion. Recurring severe insufficiency results in local necrotic areas leading to diffuse fibrosis by coalescence. Adjunctive treatment consists of bed or chair rest, a light diet, avoidance of stress, and often oxygen therapy.

Ventricular Aneurysm. Extensive transmural myocardial infarction can lead to ventricular aneurysm; however, rupture is rare. Death usually results from associated conditions rather than the aneurysm itself. Multiple small aneurysms are usually asymptomatic and do not affect longevity. Calcified and nonpulsatile aneurysms have been associated with prolonged survival, probably because they are indicative of patient adaptation capabilities.

Cardiac Rupture. Occasionally, myocardial infarction leads to cardiac rupture and is often associated with the aged. Rupture, usually fatal, is regularly associated with long-standing hypertension; less often with pre-existing left ventricle hypertrophy or coronary artery disease; and even less often with aneurysm, angina, infarction, occlusion, muscle failure, and impulse abnormalities. Preceding coronary artery disease appears to exert a protective effect against rupture because of the consequent increase in collateral circulation and the resulting muscle hypertrophy and fibrosis. While sustained hypertension on strong heart muscle facilitates rupture, protection against rupture is seen in the failing heart with decreasing blood pressure producing lowered intracavity pressure. Aged females with acute myocardial infarction are prime candidates for rupture, especially if the hypertension is of long duration.

Hypertension

Both systolic and diastolic pressure is increased in essential hypertension as the result of arteriolar vasoconstriction that increases peripheral resistance. Both systolic and diastolic pressure may be increased as the result of increased heart output as seen in thiamine deficiency, Paget's disease of bone, hyperthyroidism, and parkinsonism. Conversely, both systolic and diastolic pressure can be decreased as the result of a decreased heart output as seen in acute infarctions, heart failure, inanition, and in those disorders resulting in increased aortic length or circumference. Aortic stenosis or rigidity lowers diastolic and raises systolic pressures, resulting in a wider pulse ratio.

Keep in mind that two antagonistic disorders may be superimposed. Normal blood pressure does not necessarily prove a normal cardiovascular system; eg, when recent thiamine deficiency is superimposed on basic essential hypertension.

Pulmonary Heart DiseaseLeft Heart Failure. Changes secondary to left heart disorders and mitral disease in the elderly can adversely affect pulmonary functions. Typical dysfunctions are the result of chronic bronchitis and bronchiectasis, alveolar dilation, fibrosis and emphysema, loss of elastic tissue, chronic fibroid tuberculosis, residual fibrosis as an effect of old pulmonary infarctions, and severe kyphosis.

Right Heart Failure. Changes secondary to right heart disorders include superimposed infections, embolitoxemias, anoxemias, and other conditions that increase breathing effort. Other changes include acute cor pulmonale, which is brought forth by massive pulmonary embolus or lung infection superimposed on pre-existing atrial fibrillation and/or chronic right heart failure. Frequently diagnosed are thrombi from the veins of the lower extremities leading to pulmonary emboli. Preventive attention must be given in such cases to optimal nutrition, early ambulation, elastic stockings, care of cardiac arrhythmias and congestive heart failure, and other procedures to prevent emboli formation.

Emphysema. Pulmonary emphysema is the most common cause of chronic cor pulmonale and is difficult to diagnose until acute symptoms appear as the result of pulmonary emboli or infection, reaction from respiratory depressants, or spontaneous pneumothorax from rupture of an emphysematous bleb.

Bronchiectasis. Cyanosis and finger clubbing indicate bronchiectasis. Early signs are a lowered liver and diaphragm, distinct breath sounds, and restricted chest movements on breathing. Later signs are the result of right heart failure such as liver enlargement, distended neck veins, peripheral edema, and paroxysmal arrhythmias from coexisting coronary artery disease. The history will usually report chronic cough, dyspnea, asthmatic wheezing, several respiratory infections, heavy smoking, and/or lung resection, collapse, or some restrictive lung disease such as granulomatous, fibrotic, or infiltrative diseases.

Congenital Heart Disease

Because severe congenital heart disease shortens life span, it is rare in geriatrics except those conditions that have become well adapted until stressed by other disorders. It is not uncommon, however, to find signs in the elderly of an atrial septal defect. Before congestive heart failure appears, there will be a history of difficult breathing and several attacks of bronchopneumonia.

High pulse and blood pressure occur and likely with signs of coronary artery disease. Fluoroscopy reveals an enlarged right ventricle and atrium, a normal left atrium, a small left ventricle and aorta, and a hilar dance with a prominent pulmonary artery. Other signs include a fixed splitting of the pulmonic second sound, a low-pitched systolic murmur in the second left interspace (occasionally also at the apex and left fourth interspace), incomplete right bundle-branch block, and atrial fibrillation.

In the elderly, signs of a ventricular septal defect, an isolated pulmonic stenosis, congenital aortic lesions, a patent ductus arteriosus, or coarctation of the aorta may appear when adaptive forces are weakened.

Rheumatic Heart Disease

It is not uncommon in geriatrics to find signs of mitral insufficiency supported by a history of rheumatic fever during the younger years. Because of probable myocardial weakness and emphysema, low intensity systolic murmurs will be found localized at the apex. High blood pressure, atrial fibrillation, and atherosclerosis may be associated and hasten congestive heart failure or thromboembolism or both. However, adaptation to mitral stenosis in the elderly is commonly seen because of the decreased basal cardiac output, decreased work load, and resulting lessened stress against the narrowed mitral orifice.

Aortic and Mitral Murmurs

Aortic systolic murmurs are often the effect of degenerative processes associated with aging. Examples include fibrotic thickening of the valve cusps, aortic dilation, increased stroke output from stress, and hyperthyroidism. The extent of involvement, stenosis, calcification, fibrosis, and adhesions increase in intensity and incidence with age. Symptoms of aortic stenosis in the elderly usually include syncope, dizziness, angina, and left heart failure in association with an aortic systolic murmur. Signs include a narrow pulse pressure, a loud precordial murmur that is transmitted to the neck, a systolic aortic thrill, a faint aortic second sound, and left ventricular hypertrophy. Prognosis is poor once congestive heart failure develops. See Figure 8.7.

Degenerative changes associated with aging can involve the mitral value. The pathologic picture begins as a degeneration of collagen, progressing to lipid infiltration, fibrosis, and ending in calcification. On the other hand, mitral murmurs may be the result of anemia, cardiac dilation associated with heart muscle failure, coronary disease leading to papillary muscle dysfunction, or be due to rheumatic heart disease. Associated conditions affecting mortality in the elderly include high blood pressure, obesity, elevated serum cholesterol, albuminuria, and right bundle-branch block.

Acute and Subacute Bacterial Endocarditis

The acute variety of endocarditis is uncommon in geriatrics. When present, the rapid deterioration and high fever is often confused with diabetic acidosis, bronchopneumonia, cerebral hemorrhage, or coronary thrombosis. In the elderly, the subacute variety is more common and usually secondary to skin, sinus, dental, urinary bladder, and lower intestinal infections. Lowered endocardial resistance is often the result of heart valves being damaged by rheumatic, degenerative, or congenital diseases; especially in patients suffering from diabetes, collagen disorders, or lymphomas. Multiple, nonspecific signs and symptoms make diagnosis difficult. If the aortic valve becomes damaged, the resulting congestive heart failure offers a poor prognosis.

Luetic Heart Disease

As in subacute bacterial endocarditis, leutic heart disease offers an obscured clinical picture. While calcification of the ascending aorta may suggest a leutic condition, aortic aneurysms are more likely from arteriosclerotic and degenerative origins. Aortic insufficiency is more likely of rheumatic origin leading to aortic stenosis. While atrial fibrillation is commonly associated with luetic heart disease, tertiary lues of the CNS is rare.

Effects of Hyperthyroidism

It is not uncommon in the elderly to find chronic heart failure underlined by thyrotoxicosis, even if the hyperthyroidism is mild. Characteristics include atrial fibrillation, persistent tachycardia, dyspnea, palpitation, and reduced perspiration. However, other signs of thyroid overactivity such as tremor, weight loss, emotional disturbances, bulimia, and ocular changes may or may not exist.

Effects of Hypothyroidism

Compared to hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism is the more common geriatric condition because of the higher incidence of associated coronary artery disease. Myxedema is frequently seen in patients and associated with anemia, arthritis, mental torpor, constipation, weight gain, general weakness, and characteristic neurogenic facial signs.

Cardiac Arrhythmias and Conduction Disturbances

While not completely understood, most of these disturbances are attributed to degenerative changes affecting the common bundle and its branches, the mitral annulus, pars membranacea, central fibrous body and/or base of the aorta. Complete heart block is a common result of a severe lesion to the atrioventricular node and bundles. Muscle loss, collagen increase, and fat infiltration can involve sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes, as can coronary artery disease or occlusion.

Atrial arrhythmias and conduction disturbances can be due to a right bundle-branch block, residua of rheumatic fever, epicardium and pericardium metastases particularly from pulmonary carcinoma, hypokalemia, angina, and coronary insufficiency. While atrial fibrillation predisposes the patient to emboli infarction, premature ventricular beats may predispose ventricular tachyarrhythmia or indicate toxicity.

Congestive Heart Failure

At least half the elderly, whether ambulatory or incapacitated, show signs of congestive cardiac failure. Predisposing conditions include ischemic heart disease, cardiac hypertension, cor pulmonale, mitral insufficiencies, cardiac hypertension, mitral insufficiencies, cardiac amyloidosis, calcific aortic stenosis, pulmonary embolism, subacute bacterial endocarditis, pericarditis (chronic), thyrotoxicosis or myxedema, bronchitis, pneumonia, congenital heart disease, and especially coronary artery disease.

COMMON PERIPHERAL VASCULAR DISORDERSArterial Disorders

The arterial disorders most commonly witnessed in geriatrics are arterial embolism, arteriosclerosis obliterans, diabetic vascular lesions, and aortic and peripheral aneurysms. See Figure 8.8.

Myocardial infarction and arteriosclerotic heart disease with or without atrial fibrillation are the most common etiologic factors in arterial embolism. Emboli may arise from mural thrombi (from a silent myocardial infarction), from aortic aneurysms, or from atheromatous plaques of the aorta or its major branches. Early diagnosis is important as at least half of peripheral arterial emboli lead to gangrene of the extremities.

Clinical findings will differentiate a dissecting aneurysm, arterial spasm, or arterial thrombosis from arterial embolism. Visceral emboli occur more frequently than generally suspected, and mesenteric, renal, and cerebral emboli are not uncommon. Management must be focused on immediate attention to the ischemia and underlying heart condition.

The most common cause for ischemic lesions in the extremities is arteriosclerosis obliterans. Studies show that the process is more often localized and progressing rather than generally distributed. Involvement of a single segment of the arterial tree is not uncommon. While the progression of aortoiliac occlusion may be slow, involvement of the femoral, popliteal, or tibial arteries may cause dramatic ischemia and gangrene.

Diabetic vascular lesions are the most common cause of death in the elderly diabetic. The vascular process is widespread, involving all arterial, peripheral, and visceral areas. Lesions range in size from large arterial forms to microscopic capillary types. Diabetic neuropathy and local infection are usually associated and tend to cloud the clinical picture.

Any agent that can weaken the arterial wall can cause aneurysm. Arteriosclerosis is the most common cause in aneurysm of the abdominal aorta and the major arteries of the extremities. Approximately 75% of abdominal aorta aneurysms are found in patients in the 70s or 80s. Associated conditions include a history of angina, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, occlusive artery disease, and aneurysms of the lower extremities.

Peripheral aneurysms commonly involve the femoral and popliteal arteries and can usually be palpated during examination. Associated conditions include hypertension, coexisting cardiovascular disease, and other aneurysms of the arterial tree --especially of the abdominal or thoracic aorta. Special attention should be given to the lower dorsal and lumbar sympathetics. While rupture is the greatest concern in abdominal aortic aneurysms, thrombosis and consequent gangrene is the greatest hazard in peripheral aneurysms.

Venous Conditions

The venous disorders most commonly witnessed in the senior citizen are venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The incidence of both conditions increases with age.

Venous thrombosis is usually the result of thrombophlebitis of the lower extremities, especially of the veins of the calf as the result of chronic ailments and/or lack of exercise such as in convalescence. Thrombophlebitis of the iliofemoral segment, the inferior vena cava, and the superficial veins of the lower extremities are also common. Any condition leading to stasis and coagulation in the venous system can encourage thrombophlebitis and increase the risk of pulmonary embolism. While most thrombi occur in the venous plexus of the lower extremities, some occur in the pelvis and heart. Danger occurs when a lower thrombus may detach with the embolus migrating to the right heart with possible progression to the lungs.

COMMON HEMATOLOGIC DISORDERSNormal Variations

While geriatric anemia is common, the cause appears to be more commonly attributed to life-style rather than physiologic processes. Many reports indicate a change in the erythrocyte system, the leukocyte system, platelet and blood coagulation, and bone marrow, but other studies show insignificant changes attributable to age alone.

Aging and Hematologic Resources

Certain physiologic alterations during aging have been shown to affect the hematopoietic apparatus, which in turn affects the senior citizen's ability to adapt to environmental stresses and lowers resistance (both bacterial and viral). Characteristic of these alterations are lymph node and thymus atrophy, and decreased testosterone levels resulting in reduced circulating erythropoietin.

Frequently in the elderly, immunologic alterations encourage lymphoproliferative disorders such as lymphosarcoma, macroglobulinemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, reticulum cell sarcoma, and multiple myeloma. Several changes in bone marrow occur, but it is difficult to determine whether these are from chronic disorders or senescence. These changes are reflected in decreased hematopoietic cells with alteration of their ratio and increased reticuloendothelial system cells and tissue mast cells --probably the result of hormone imbalance.

Anemia, splenomegaly, or other clinical findings of hematologic disorder must be evaluated in geriatrics from the same viewpoint as held for younger patients, with the possible exception that the malignant or lymphoproliferative disorders have a higher incidence and thus demand greater concern.

Hemorrhagic Diathesis

While congenital hemorrhagic disorders are extremely rare in the senior citizen, several types of the acquired variety are witnessed. Symptomatic thrombocytopenia due to leukemia, aplastic anemia, and allied disorders are frequently observed. A tendency to hemorrhage may be noticed in patients with hepatic or renal insufficiency, marrow cancer, weakened blood vessels, or disorders affecting platelet dysfunction or enhanced fibrinolyses. Metastatic cancer, promyelocyte leukemia, and dysproteinemia are also associated conditions.

Leukemia and the Proliferative Disorders

Acute leukemia is not a rare geriatric condition; rather, it is often insidious on onset. Three acute and four chronic myeloproliferative disorders are seen in the elderly that frequently overlap or shift to one another. The acute disorders are acute granulocytic leukemia and acute myelosclerosis with myeloid metaplasia. The chronic disorders include chronic myeloid leukemia, polycythemia vera, thrombocythemia, and chronic myelosclerosis with myeloid metaplasia. Common features of these disorders are the proliferation of one or more lines of bone marrow elements (of a self-perpetuating character) and the absence of a demonstrable cause of the proliferation.

The incidence of polycythemia and myelosclerosis with myeloid metaplasia increases with age. Patients presenting with myelosclerosis and myeloid metaplasia typically show spleen enlargement, possible liver involvement, bone marrow fibrosis, and leukoerythroblastic anemia. The most common disorders are chronic lymphoid leukemia, Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia, and myelomatosis. Other disorders classified as proliferative disorders seen in the elderly include lymphosarcoma, giant follicular lymphoma, reticulum cell sarcoma, and Hodgkin's disease.

Chronic lymphoid leukemia also has a high incidence in senior citizens and can take the benign form with few clinical symptoms or take the aggressive form exhibiting an intense clinical picture. The more common benign form is characterized by slow progress, unprominent splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy, decreasing gamma globulins and granulocytes, and a leukocyte count often remaining in a range of 15,000 to 50,000 per cubic millimeter.

Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia is characterized by lymphocytes secreting an abnormal amount of high-molecular gamma globulin and the proliferation of atypical lymphocytes. It is associated with bleeding tendencies and mild hepatosplenomegaly and lymphadenopathy.

Myelomatosis is also a condition witnessed in patients over 50 years of age. In this disorder, the myeloma cells proliferate at extra- and intra-medullary sites. During the advanced state, rheumatic or neuralgic pain, nephritis like changes in the urine, an increased sedimentation rate, and anemia are characteristic.

Iron-Deficiency Anemia

This disorder more common in the young than in the elderly, yet it is the most common anemia of the elderly. Peptic ulcers, hemorrhoidal bleeding, and diaphragmatic hernia are the main etiologic factors in geriatrics. Clinical features include a microcytic hypochromic anemia associated with a lowered serum iron level and an increased unsaturated iron-binding capacity (UIBC). Gastric carcinomas in men and women and gynecologic cancer in women should always be considered. Achlorhydria may be a precipitating factor.

In late stages, characteristic tissue and epithelial changes occur such as thin, pliable, and brittle fingernails having longitudinal ridging progressing to koilonychia; dry inelastic skin; thin brittle hair; tongue atrophy progressing to Plummer-Vinson syndrome; and other signs attributable to impaired tissue nutrition because of depleted iron-containing enzymes. Treatment is the same as for younger age groups.

Pernicious Anemia

While not as common in the elderly as iron-deficiency anemia pernicious anemia is almost exclusively (in this country) associated with old age. In contrast to iron-deficiency anemia, pernicious anemia is a disorder of the whole hematopoietic apparatus, which includes general cellular metabolism, and results in a pancytopenia with reduction in white cells and platelets as well as anemia.

In contrast, iron-deficiency anemia is hypochromic and microcytic but pernicious anemia is normochromic and macrocytic. This latter condition is truly a nutritional anemia -- the fundamental cause being B-12 deficiency.

Injectable B-12 appears to be more efficient than oral supplementation in stabilizing the patient.

Clinical signs of pernicious anemia besides the hematologic abnormalities include marked tongue atrophy with flattened papillae, yellow pallor of the skin, prematurely gray or white hair, and hepatosplenomegaly. In advanced stages, all levels of the central and peripheral nervous system can be involved, resulting in profound neurologic lesions. The condition is characterized by a loss of vibration sense over the toes, loss of proprioception sense, loss of Achilles or patellar reflexes, paresthesias, and possible dementia. Associated or subsequent gastric carcinoma should be considered. In spontaneous myxedema, a megaloblastic anemia may develop that is indistinguishable from pernicious anemia.

Folic Acid Deficiency

Folic acid deficiency is another common factor in geriatric anemia. Deficiency affects DNA synthesis much the same as B-12 deficiency. Clinically, the epithelial and neurologic pictures are not as widespread or as severe. Here, diet is more important as the body does not store folic acid in quantities as it does for B-12. The condition is commonly associated with alcoholism and often blended with the features of cirrhosis and fatty liver.

While maintenance therapy is usually life-long in pernicious anemia, it need not be so in folic acid deficiency. Return to normal hematopoiesis is more often the rule than the exception. Studies show that folic acid deficiency is almost always associated with vitamin C deficiency, which compounds the condition as ascorbic acid acts as a cofactor aiding in the reduction of folic acid to its active coenzyme form.

Other Nutritional Anemias

Deficiencies of riboflavin, niacin, B-6, and vitamin E have also been attributed to deficiency anemias, but these are rare in the elderly.

Symptomatic Anemias

The so-called symptomatic anemias are those related to an underlying disease and represent a major category in the anemias of the elderly. While all types of cancer represent the foremost disorders involved, renal failure anemia, chronic infection anemia, and uremic anemia are occasionally seen.

COMMON DIGESTIVE AND GASTROENTEROLOGIC DISORDERSThe digestive system of the elderly probably causes more discomfort, distress, and annoyance than any other system in the body. This is as much to following misinformation as it is to specific disorders. On the other hand, a doctor should not be too eager to drastically alter senior citizens' diets. The elderly have had may years of experimentation and have acquired through trial and error a good idea of what they can and cannot easily digest. Biologic adaptation to some unusual diets and eating customs is common. Nevertheless, certain aging processes in the elderly predispose digestive and gastroenterologic disorders.

Progressively with age, secretions of hydrochloric acid and the digestive enzymes of the stomach, pancreas, liver, and intestines diminish. Motility of the gastrointestinal tract becomes modified. Muscular atrophy of the small and large intestines occurs along with a decrease in mucus secretion, which contributes to constipation. Habits and life-style often lead to weakened abdominal muscles, general inactivity, anorexia, and inadequate fluid intake. Habitual frequent use of laxatives may be a problem.

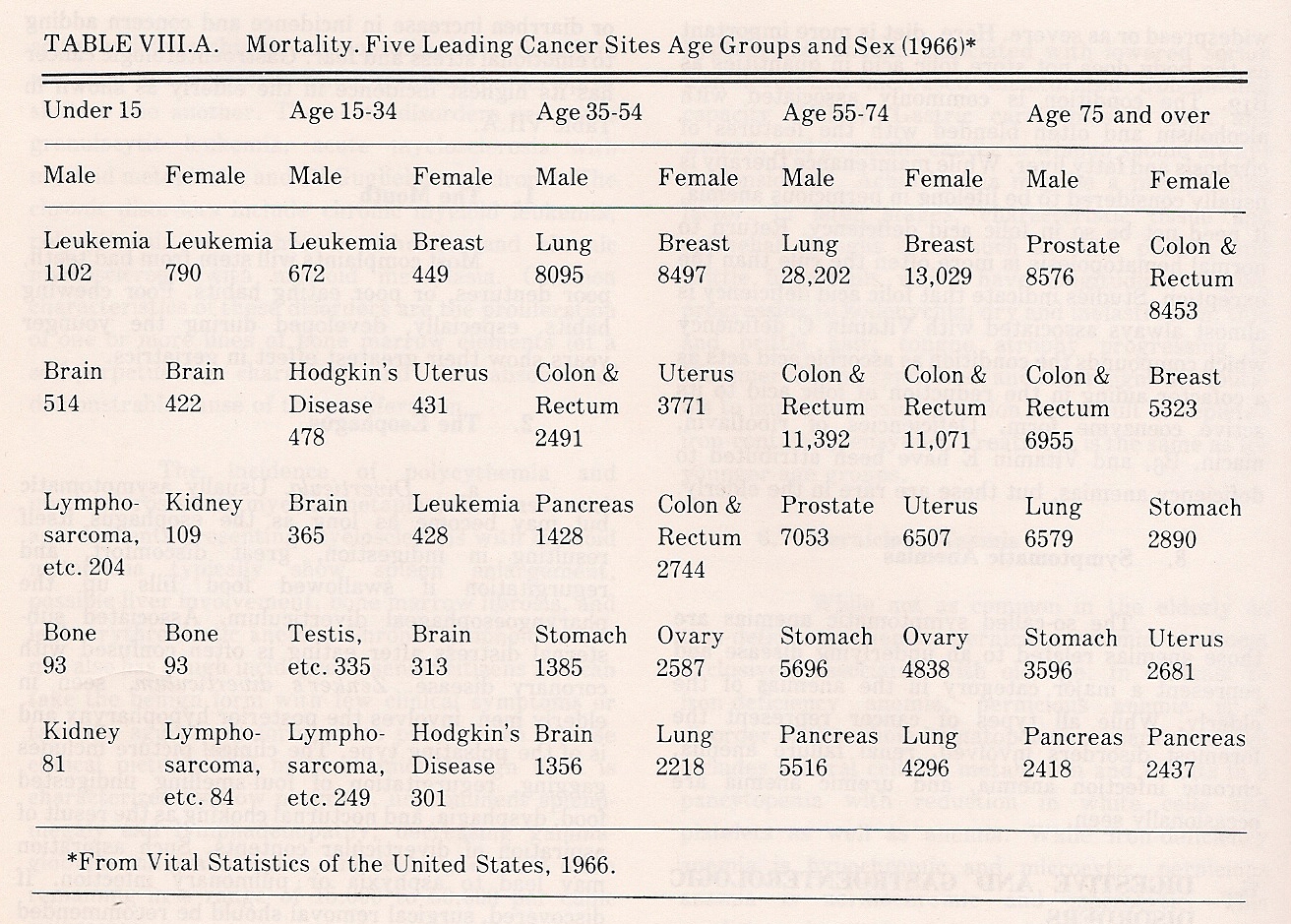

Protein undernutrition may lead to hepatic fatty infiltration, and cirrhosis gives the same picture as found in younger groups. Symptoms of heartburn, gas, dyspepsia, flatulence, constipation, or diarrhea increase in incidence and concern, adding to emotional stress and fear. Gastroenterologic cancer has its highest incidence in the elderly. See Table 8.1

Table 8.1. Mortality in Five Leading Cancer Sites, Age Groups, and Sex

The Mouth

Most geriatric complaints stem from bad teeth, poor dentures, or poor eating habits. Poor chewing habits developed during the younger years show their greatest effect in late life. See Figure 8.9.