|

Chapter 25:Physiologic or Anatomic Short Leg Postural Patterns Contusions and Strains Sprains and Subluxations Fractures and Dislocations Injuries of the Hip Contusions and Strains Trochanteric Bursitis Causalgia Syndrome Hip Sprain Subluxations Fractures and Dislocations

Lumbar Spine, Pelvic, and Hip Injuries

From R. C. Schafer, DC, PhD, FICC's best-selling book:

“Chiropractic Management of Sports and Recreational Injuries”

Second Edition ~ Wiliams & Wilkins

The following materials are provided as a service to our profession. There is no charge for individuals to copy and file these materials. However, they cannot be sold or used in any group or commercial venture without written permission from ACAPress.

All of Dr. Schafer's books are now available on CDs, with all proceeds being donated

to chiropractic research. Please review the complete list of available books.

Lumbar Spine Injuries Initial Assessment Contusions andStrains Facet Syndromes Acute Lumbosacral Sprain Acute Lumbosacral Angle Lumbosacral Instability Basic Neurologic Aspects of Lumbar Subluxation Syndromes Spinal Cord Injuries Intervertebral Disc Syndrome Spondylolisthesis Lumbar Spondylolysis Subluxations, Fractures, and Dislocations Injuries of the Pelvis

Chapter 25: Lumbar Spine, Pelvic, and Hip Injuries

Low back disability, amounting to up to 25% of all athletic injuries, rapidly demotivates athletic participation. For biomechanical reasons, the incidence of injury is two times higher in taller athletes than shorter players. The mechanism of injury is usually intrinsic rather than extrinsic. The cause can often be through overbending, a steady lift, or a sudden release --all of which primarily involve the musculature. Intervertebral disc conditions are more often, but not exclusively, attributed to extrinsic blows and wrenches. An accurate and complete history is vital to offer the best management and counsel.

Tenderness. Tenderness is frequently found at the apices of spinal curves and rotations and not infrequently where one curve merges with another. Tenderness about spinous or transverse processes is usually of low intensity and suggests articular strain. Tenderness noted at the points of nerve exit from the spine and continuing in the pathway of the peripheral division of the nerves is a valuable aid in spinal analysis; however, the lack of tenderness is not a clear indication of lack of spinal dysfunction. Tenderness is a subjective symptom influenced by many individual structural, functional, and psychologic factors which often makes it an unreliable sign. Always evaluate the presence and symmetry of lower-extremity pulses.

(1) alongside the T12 spinous process,

(1) If there is a right structural scoliotic deviation of the lumbar area, the patient sitting straddle on a bench to fix the pelvis will find it easier to rotate the torso to the right than to the left.

The transition points of the spinal curvatures (ie, the atlanto-occipital, cervicobrachial, thoracolumbar, and lumbosacral points) serve as mobile differentials about which flexion, extension, circumflexion, circumduction, and compensatory scoliotic deviations should occur. If these areas are kept mobile, the adaptive, compensatory, and ordinary motor functions of the spine are enhanced.

Passive Stretch. Mild passive stretch is an excellent method of reducing spasm in the long muscles, but heavy passive stretch destroys the beneficial reflexes. For example, hypertonic erector muscles of the spine can be simply relaxed by placing the patient prone on a split head-piece adjusting table and tilting the abdominal and pelvic section upward to flex the spine. The weight of

the structures above and below the midpoint of the flexed spine offer a mild stretching effect, both cephally and caudally. The muscles should relax within 2-3 minutes. Thumb pressure, placed on a trigger area, is then directed towards the muscle's attachment and held for a few moments until relaxation is complete. Psoas or quadriceps spasm can be relaxed with Braggard's test by holding the straight leg for a minute or two in extension and dorsiflexing the foot.

Any method of spinographic interpretation which utilizes millimetric measurements from any set of preselected points is most likely to be faulty because structural asymmetry and minor anomaly is universal in all vertebrae. However, the estimation of the integrity of facet joints is a reliable method of assessing the presence of intervertebral subluxation. An evaluation of the alignment of the articular processes comprising a facet joint may be difficult from the A-P or P-A view alone when the plane of the facet facing is other than sagittal or semisaggital. In this case, oblique views of the lumbosacral area are of great value in determining facet alignment since the joint plane and articular surfaces can nearly always be visualized. With the patient standing with feet moderately apart, the doctor from behind the patient firmly wraps his arms around the patient's pelvis and firms his lateral thigh against the back of the patients' pelvis. The patient is asked to bend forward. If it is a facet involvement, the patient will feel relief. If it is a disc that is stressed, symptoms will be aggravated.

In facet involvement, the patient seeks to find relief by sitting with feet elevated and resting upon a stool, chair, or desk. In disc involvement, the patient keeps knees flexed and sits sideways in his chair and moves first to one side and then to the other for relief. If lumbosacral and sacroiliac pain migrates from one to the other side, it is suspected to be associated with arthritic changes.

MANAGEMENT

The lumbar spine, sacrum, ilia, pubic bones, and hips work as a functional unit. Any disorder of one part immediately affects the function of the other parts. A wide assortment of muscle, tendon, ligament, bone, nerve, and vascular injuries in this area are witnessed during athletic care.

Lumbar Spine Injuries

Initial Assessment

The first step in the examination process is knowing the mechanism of injury if possible. With this knowledge, evaluation can be rapid and accurate. A player injured on the field should never be moved until emergency assessment is completed. Once severe injury has been eliminated, transfer to a back board can be made and further evaluation conducted at the aid station.

RANGE OF MOTION

The range of lumbar spine motion is determined by the disc's resistance to distortion, disc thickness, and the angle and size of the articular surfaces. While motion is potentially greater than that of the thoracic spine because of lack of rib restriction, facet facing and heavy ligaments check the range of motion. Most significant to movements in the lumbar spine is the fact that all movements are to some degree three dimensional; ie, when the lumbar spine bends laterally, it tends to rotate posteriorly on the side of convexity and assume a hyperlordotic tendency.

The transitional lumbosacral area of L5-S1 constitutes a rather unique "universal joint"; eg, when the sacrum rotates anterior-inferior on one side within the ilia, L5 tends to rotate in the opposite direction, thus effecting a mechanical accommodation with the lumbar spine above assuming a posterior rotation on the side of the unilateral anterior-inferiority. It also tends to assume an anteroflexion position, thus effecting the three-dimensional movements of the lumbar spine. In view of the intricacy of the lumbosacral junction, anomalies such as asymmetrical facets have a strong influence on normal movements in this area.

If lumbar active motions are normal, there is no need to test passively. A patient may be observed, however, who replaces normal lumbar motion by exaggerated hip motion, or vice versa. In such a situation, range of motion of the restricted lumbar or hip joints should be passively tested.

During flexion of the lumbar spine, the anterior longitudinal ligaments relax and the supraspinal and interspinal ligaments stretch. Flexion will not normally result in a kyphosis of the lumbar area as flexion may do in the cervical area. While a number of disorders result in decreased flexion, paraspinal muscle spasm is the first suspicion. The degree of extension is controlled by stretching of the anterior longitudinal ligament and rectus abdominis muscles, relaxation of the posterior ligaments, and integrity of the intrinsic motor muscles of the back. If spondylolisthesis exists, pain will be increased during extension.

EVALUATING NEUROLOGIC LEVELS OF THE LOWER EXTREMITIES

A sensory and motor neurologic assessment should be made as soon as possible. Determine tonus (flaccidity, rigidity, spasticity) by passive movements. Then test voluntary power of each suspected group of muscles against resistance, and compare the force bilaterally. Test cremasteric (L1-L2), patellar (L2-L4), gluteal (L4-S1), suprapatellar, Achilles (L5-S2), plantar (S1-S2), and anal (S5-Cx1) Reflexes. Note patellar or ankle clonus. Test coordination and sensation by gait, heel-to-knee and foot-to-buttock tests, and Romberg's station test.

TRIGGER POINTS

Trigger points for the lumbosacral and sacroiliac articular complexes are commonly located

(2) alongside the L5 spinous process,

(3) over the greater sciatic notch through the gluteal muscles,

(4) over the crest of the ilium,

(5) over the belly of the tensor fascia lata muscle,

(6) in the ischiorectal fossa apex, and

(7) at the sciatic outlet onto the back of the thigh from under the gluteus maximus.

DISTORTION PATTERNS

A unique feature of a spinal and pelvic distortion or subluxation is the fact that the segment or segments can be carried into the deviation of the distortion pattern much more readily than out of the gravitational pattern of the deviation. The following examples illustrate this:

(2) If an innominate in subluxation has rotated to the posterior on the right, the patient is able to raise the right knee (thus rotating the ilum posteriorly) noticeably higher than the left knee. But it is more difficult for the patient to extend the right thigh (thus rotating the ilium anteriorly) than the left thigh.

(3) If there is a left wedging of L5, L4, or L3, lateral flexion to the left is noticeably easier than lateral flexion to the right.

Contusions and Strains

Fortunately, most injuries seen will involve uncomplicated contusions and subluxations of the spinal area and adjacent free ribs that are relatively easy to manage. However, severe contusion of the lumbodorsal fascia is occasionally seen which frequently leads to an extensive painful hematoma. When severe injury does occur, the type widely varies from sport to sport. In some cases, a silent condition such as a spina bifida occulta may only be brought to light through strenuous athletic activity.

LOAD CONSIDERATIONS

The importance of spinal loads is underscored with weight lifters, bowlers, oarsmen from lifting the shell, and even in lordotic long-distance runners. It has been estimated that when an object is held 14 inches away from the spine, the load on the lumbosacral disc is 15 times the weight lifted. Lifting a 100-lb weight at arms' length theoretically places a 1,500-lb load on the lumbosacral disc. This load, of course, must be dissipated, otherwise the L5 vertebra would crush. The load is dissipated through the paraspinal muscles and, importantly, by the abdominal cavity which acts as a hydraulic chamber absorbing and diminishing the load applied. These observations on spine loading emphasize the vulnerability of the spine to the mechanical stresses placed upon it, especially in people with poor muscle tone. Bony compression of the emerging nerve roots arises as a result of subarticular entrapment, pendicular kinking, or foraminal impingement due to posterior vertebral subluxation.

MUSCLE SPASMS

General spasm of the spinal muscles guarding motion in the vertebral joints can be viewed by watching body attitude (eg, stiff carriage) and by efforts to bend the spine forward, backward, and to the sides. If we are familiar with the average range of motility in each direction and at different ages, this test is usually easy and rapid. Backward bending is the least satisfactory; and in doubtful cases, the patient should be prone while the examiner, standing over him, lifts the whole trunk by the feet.

MANAGEMENT

The benefits of articular adjustments are well known within the profession. To relieve muscle spasm, heat is helpful, but cold and vapocoolant sprays have sometimes shown to be more effective. The effects of traction are often dramatic but sometimes short-lived if a herniated disc is involved. A predisposing ankle or arch weakness may be present which requires special stabilization.

Vapocoolant Technique in Acute Low Back Muscle Spasms. NOTE: At one time "spray and stretch" was a popular form of treatment for Trigger Points. That form of sustained contraction of muscle is amenable to several techniques. The first, and least popular with patients is called "ischemic pressure" (NIMMO), involving deep and sustained pressure on the point. Cold and pressure receptors in the skin are inhibitory to the gamma motor neurons that appear to sustain the viscious-cycle contraction of TrPs. PIR (or post-isometric relaxation) is a slower and kinder to the patient method for disrupting sustained muscle spasm. The CFC sprays were taken off the market in the 90s, when CFCs (chloro-fouoro-carbon) were outlawed for their deleterious impact on the ozone layer.

Adjuncts. Other methods may prove helpful. Peripheral inhibitory afferent impulses can be generated to partially close the presynaptic gate by acupressure, acupuncture, or transcutaneous nerve stimulation. Isotonic exercises are useful in improving circulation and inducing the stretch reflex when done supine to reduce exteroceptive influences on the central nervous system. An acid-base imbalance from muscle hypoxia and acidosis may be prevented by supplemental alkalinization. In chronic cases, relaxation training and biofeedback therapy are helpful.

Facet Syndromes

The subluxation of lumbar facet structures, states Howe, is a part of all lumbar dyskinesias and must be present if a motor unit is deranged. In a three-point articular arrangement, such as at each vertebral motor unit, no disrelationship can exist that does not derange two of the three articulations. Thus, determination of the integrity or subluxation of the facets in any given motor unit is important in assessing that unit's status.

ROENTGENOLOGIC CONSIDERATIONS

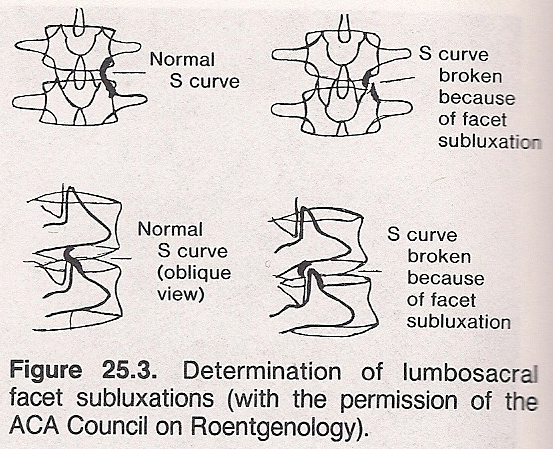

When one cannot visually identify disrelationships of the facet articular structures, Howe suggests use of Hadley's S curve. This is made by tracing a line along the undersurface of the transverse process at the superior and bringing it down the inferior articular surface. This line is joined by a line drawn upward from the base of the superior articular process of the inferior vertebrae of the lower edge of its articular surface. These lines should join to form a smooth S. If the S is broken, subluxation is present. This A-P procedure can be used on an oblique view.

DIFFERENTIATION

To help differentiate the low back and sciatic neuralgia of a facet syndrome to that of a disc that is protruding:

The associated pain, accentuated by hyperextension of the trunk, results when an inferior apophyseal facet becomes displaced upward so that it impinges on the IVF contents of the inferior vertebral notch (eg, nerve root) of the superior vertebra. Cryotherapy and other forms of pain control are advisable during the acute stage for 48 hours. Considerable relief will be achieved by placing the patient prone with a roll under the lower abdomen to flex the lumbar spine while applying manual traction techniques. This should be followed by corrective adjustments to relieve associated fixations and abnormal biomecha- nics, traction, and other physiotherapy modalities. A regimen of therapeutic exercises and shoe inserts designed to improve postural balance and lessen gait shock are helpful during recuperation.

Various neurologic and orthopedic procedures relative to lumbosacral syndromes are listed in Table 25.1.

Table 25.1. Review of Neurologic and Orthopedic Manuevers, Reflexes, Signs, or Tests Relative to Lumbosacral Syndromes

Achilles' reflex Ely's heel-to-buttock Milgram's test Adams' sign test Minor's sign Adductor reflex Fajersztajn's test Muscle strength grading Anal reflex Gaenslen's test Nachlas' test Babinski's Giegel's reflex Naffziger's test plantar Gluteal reflex Neri's bowing sign reflex Goldthwait's test Neri's test Babinski's Gower's sign O'Connell's test sciatic sign Hamstring reflex Patella reflex Barre's sign Heel walk test Pitres' sign Bechterew's test Hyperextension tests Range of motion tests Beery's sign Jandrassik's maneuver Romberg's station test Belt test Kemp's test Sicard's sign Bonnet's sign Kernig's sign Smith-Peterson's test Bowstring sign Lasegue's Spinal percussion test Bragard's test differential Toe walk test Buckling sign sign Turyn's sign Cremasteric Lasegue's SLR Vanzetti's sign reflex test Westphal's sign Dejerine's triad Lewin's punch Yeoman's test Demianoff's sign test Deyerle-May's Light touch/ test pain tests Double leg Lindner's sign raise test Duchenne's sign

Acute Lumbosacral Sprain

These sprains are of frequent appearance. Heavy loads or severe blows may rupture some associated ligaments and/or subluxate the joint. Pain may be local or referred. Symptoms are usually relieved by rest and aggravated by activity. Care must be taken to differentiate from a sacroiliac or hip lesion. Localized tenderness and the various clinical tests are helpful in differentiation.

Management. During the acute hyperemic stage, structural alignment, cold, compression support, ultrasound, and rest are indicated. After 48 hours, passive congestion may be managed by gentle passive manipulation, sinusoidal stimulation, ultrasound, and a mild range of motion exercise initiated. During consolidation, local moderate heat, moderate active exercise, motorized alternating traction, moderate range of motion manipulation, and ultrasound are beneficial. In the stage of fibroblastic activity, deep heat, deep massage, vigorous active exercise, motorized alternating traction, negative galvanism, ultrasound, and active joint manipulation speed recovery and inhibit postinjury effects. Vitamin C and manganese glycerophosphate are helpful throughout treatment to speed healing.

Acute Lumbosacral Angle

In this condition, Olsen states that the acute angulation of L5 on S1 is twofold:

(1) There is bursal involvement due to an overriding of the facets which stretches the bursa.

(2) There is a narrowing of the intervertebral foramen (IVF) causing a telescoping from the superior to the inferior of the facet joints. Radiologically, the type of bursitis cannot be defined. Orthopedically, the problem is described as the facet-pain syndrome.

Cartilage is found between all articular surfaces, and undue stress during weight bearing on the facets can cause injury to the cartilage which will progress with degenerative changes. The degeneration may cause L5 to slip forward (degenerative disc disease), portray decreased disc space (discogenic disease), or exhibit decreased space with eburnation (discopathy). Sacralization is the only time when it is normal to have a decreased disc space, unless the disc is underdeveloped (hypoplasia). Along with the facet syndrome, there may also be an increased lordosis of the lumbar spine.

The facet syndrome can occur with

(1) the anteriorly based sacrum with a normal lordosis;

(2) the anteriorly based sacrum with an accentuated lordosis;

(3) the anteriorly based sacrum with a "sway back"; or

(4) a normally based sacral angle and the "sway back" type of individual.

Evaluation is made by drawing a line through the superior border of the sacral base and through the inferior border of L5. If these lines cross within the IVF or anterior to it, this indicates a facet syndrome. Olsen recommends the use of Fergurson's angle, where the body of L3 is X'ed and a line is dropped perpendicular from the center of the vertebral body. This line normally falls over the sacral prominatory or the anterior edge of the sacrum and reveals normal lumbosacral weight bearing (Fergurson's line of gravity). The L5 disc spacing is seen normally as symmetrical with the one above, and the actual weight bearing is on the nucleus pulposus.

A persistent notochord may be seen where the disc is normal but embedded into the body of the vertebra. This is seen in a postural facet syndrome where the anterior disc space is wide at the expense of narrowed disc space posteriorly and the body of the vertebra has rocked on the nucleus. It is not pathologic. For example, a normal vertebra presents decreased disc space posteriorly with the lines crossing in the IVF. There is normal disc space anteriorly, but in order for this to happen, there is a herniation. The disc is normal, but the symmetry of the disc interspace is broken.

Lumbosacral Instability

Lumbosacral instability is a mechanical aberration of the spine which renders it more susceptible to fatigue and/or subsequent trauma by reason of the variance from the optimal structural weight-bearing capabilities. Hariman states that between 50% and 80% of the general population exhibit some degree of the factors which predispose to instability whether by reason of anomalous development of articular relationships or altered relationships due to trauma or disease consequences. It is the most common finding of lumbosacral roentgenography and often brought to light after an athletic strain.

Disturbance of the physiologic response of the spinal motor unit is the primary finding with the sequela of "stress response syndrome" which may take the form of any degree between sclerosis of a tendon to and including an ankylosing hypertrophic osteophytosis or arthrosis. Frequent trauma to the articular structures as a result of excessive joint motility results in repetitive microtrauma. The scope of involvement and the tissue response is determined by the type and severity of the instability.

Signs and Symptoms. Unusual early fatigue is a constant symptom, and this leads to strain, sprain, and subsequent disc pathologies. Symptom susceptibility increases with the age of the individual. Postural evaluation is especially important in the physical diagnosis of the sequelae as well as to an extra-spinal causation (eg, anatomic short leg).

Roentgenographic Considerations. Roentgen diagnosis is the only sure manner of delineating the type and severity of the underlying productive agent of the condition of instability. There is no characteristic finding except the recognition of the various anomalies and pathologies present. Care should be taken to include the entire pelvis in this determination as, for instance, a sacroiliac arthrosis may lead to instability.

Management. This condition often requires supportive therapies such as heel lifts and/or orthopedic belts in addition to specific adjustive therapy directed toward stabilization of the motor unit. Hariman feels the prognosis is excellent with adjustive and supportive management. High doses of vitamin C with calcium and magnesium have also proved helpful in disc conditions. Efforts and counsel should be directed to minimize the production of future microtrauma. Loss of stability and compensation due to injury in the future may be expected to reproduce symptoms in an exaggerated form.

PERTINENT PROCEDURES IN LUMBOSACRAL SYNDROMES

Giegel's (Inguinal) Reflex. With the patient supine, the skin of the upper thigh is stimulated from the midline toward the groin. A normal response is an abdominal contraction at the upper edge of Poupart's ligament. This reflex (L1--L2) is essentially the female counterpart of the cremasteric reflex in the male.

Adductor Reflex. With the patient supine and the thigh moderately abducted, a normal response is seen when the tendon of the adductor magnus is tapped and a contraction of the adductor muscles occurs. This reflex reaction tests the integrity of the obturator nerve and L2–L4 segments of the spinal cord, as does the patellar reflex.

Hamstring Reflex. The patient is placed supine with the knees flexed and the thighs moderately abducted. The tendons of the semitendinosus and semimembranosus are hooked by the examiner's index finger and the finger is percussed. Normally, a palpable contraction of the hamstrings occurs. An exaggerated response indicates an upper motor neuron lesion above L4, and it may be associated with a reflex flexion of the knee (Stookey response). An absent response signifies a lower motor neuron lesion affecting the L4–S1 segments, as do absent Achilles and plantar reflexes.

Heel Walk Test. A patient should normally be able to walk several steps on the heels with the forefoot dorsiflexed. With the exception of a localized heel disorder (eg, calcaneal spur) or contracted calf muscles, an inability to do this because of low back pain or weakness can suggest an L5 lesion.

Toe Walk Test. Walking for several steps on the base of the toes with the heels raised will normally produce no discomfort to the patient. With the exception of a localized forefoot disorder (eg, plantar wart, neuroma) or an anterior leg syndrome (eg, shin splints), an inability to do this because of low back pain or weakness can suggest an S1–S2 lesion.

Double Leg Raise Test. This is a two-phase test:(1) The patient is placed supine, and a straight-leg-raising (SLR) test is performed on each limb: first on one side, and then on the other.

(2) The SLR test is then performed on both limbs simultaneously; ie, a bilateral SLR test. If pain occurs at a lower angle when both legs are raised together than when performing the monolateral SLR manuever, the test is considered positive for a lumbosacral area lesion.O'Connell's Test. This test is conducted similar to that of the double leg raise test except that both limbs are flexed on the trunk to an angle just below the patient's pain threshold. Then the limb on the opposite side of involvement is lowered. If this exacerbates the pain, the test is positive for sciatic neuritis.

Nachlas' Test. The patient is placed in the prone position. The examiner flexes the knee on the thigh to a right angle, then, with pressure against the anterior surface of the ankle, the heel is slowly directed straight toward the homolateral buttock. The contralateral ilium should be stabilized by the examiner's other hand. If a sharp pain is elicited in the ipsilateral buttock or sacral area, a sacroiliac disorder should be suspected. If the pain occurs in the lower back area or is of a sciatic-like in nature, a lower lumbar disorder (especially L3–L4) is indicated. If pain occurs in the upper lumbar area, groin, or anterior thigh, quadriceps spasticity/contacture or a femoral nerve lesion should be suspected.

Gower's Maneuver. The patient uses the hands on the thighs in progressive short steps upward to extend the trunk to the erect position when arising from a sitting or forward flexed position. This sign is positive in cases of severe muscular degeneration (eg, muscular dystrophy) of the lumbopelvic extensors or a bilateral low back disorder (eg, spondylolisthesis).

Hyperextension Tests. These two tests help in localizing the origin of low back pain.(1) The patient is placed prone. With one hand the doctor stabilizes the contralateral ilium, and the other hand is used to extend the patient's thigh on the hip with the knee slightly flexed. If pain radiates down the front of the thigh during this extension, inflamed L3–L4 nerve roots should be suspected if acute spasm of the quadriceps or hip pathology have been ruled out.

(2) With the patient remaining in the relaxed prone position, the examiner stabilizes the patient's lower legs and instructs the patient to attempt to extend the spine by lifting the head and shoulders as high as possible from the table by extending the elbows bilaterally. If localized pain occurs, the patient is then asked to place a finger on the focal point.Also see Adam's sign, Bechterew's test, Beery's sign, Forestier's bowstring sign, Bragard's test, Fajersztajn's test, Goldthwait's test, Gower's manuever, Hibb's test, Kemp's test, Kernig's sign, Lasegue's SLR test, Minor's sign, Naffziger's test, Neri's bowing sign, Neri's test, and Smith-Peterson's test, and Westphal's sign.

Basic Neurologic Aspects of Lumbar Subluxation Syndromes

Disturbances of nerve function associated with subluxation syndromes manifest as abnormalities in sensory interpretations and/or motor activities. These disturbances may be through one of two primary mechanisms: direct nerve or nerve root disorders, or of a reflex nature.

NERVE ROOT INSULTS

When direct nerve root involvement occurs on the posterior root of a specific neuromere, it manifests as an increase or decrease in awareness over the dermatome; ie, the superficial skin area supplied by this segment. Typical examples might include forminal occlusion or irritating factors exhibited clinically as hyperesthesia, particularly on the

(1) anterolateral aspects of the leg, medial foot, and great toe, when involvement occurs between L4-L5; and

(2) posterolateral aspect of the lower leg and lateral foot and toes when involvement occurs between L5-S1.

In other instances, this nerve root involvement may cause hypertonicity and the sensation of deep pain in the musculature supplied by the neuromere; for example, L4 and L5 involvements, with deep pain or cramping sensations in the buttock, posterior thigh and calf, or anterior tibial musculature. In addition, direct pressure over the nerve root or distribution may be particularly painful.

Reflexes. Nerve root insults from subluxations may also be evident as disturbances in motor reflexes and/or muscular strength. Examples of these reflexes include the deep tendon reflexes such as seen in reduced patella and Achilles tendon reflexes when involvement occurs between L4-L5. These reflexes should also be compared bilaterally to judge whether hyporeflexia is unilateral; unilateral hyperreflexia is highly indicative of an upper motor neuron lesion.

Atrophy. Prolonged and/or severe nerve root irritation may also cause evidence of trophic changes in the tissues supplied. This may be characterized by obvious atrophy which would be rare in athletics. Such a sign is particularly objective when the circumference of an involved limb is measured at the greatest girth in the initial stage and this value is compared to measurements taken in later stages.

Kemp's Test. While in a sitting position, the patient is supported by the examiner who reaches around the patient's shoulders and upper chest from behind. The patient is directed to lean forward to one side and then around to eventually bend obliquely backward by placing his palm on his buttock and sliding it down the back of his thigh and leg as far as possible. The maneuver is similar to that used in cervical compression. If this compression causes or aggravates a pattern of radicular pain in the thigh and leg, it is a positive sign and indicates nerve root compression. It may also indicate a strain or sprain and thus be present when the patient leans obliquely forward or at any point in motion.

Since the elderly weekend athlete is less prone to an actual herniation of a disc due to lessened elasticity involved in the aging process, other reasons for nerve root compression are usually the cause. Degenerative joint disease, exostoses, inflammatory or fibrotic residues, narrowing from disc degeneration, tumors -- all must be evaluated.

SCIATIC IRRITATION

Although it is the largest nerve of the body and supplies through its branches all the muscles below the knee, the sciatic nerve is rarely injured by sudden trauma. It is often affected, however, by sciatic neuritis (sciatica) which is frequently due to intermittent trauma. Sciatic neuralgia or neuritis is characterized by pain of variable intensity to a maximum that is almost unbearable. The pain radiates from the sacroiliac area down the posterior thigh and even to the sole of the foot. Muscular atrophy and the characteristic limp are usually present.

Sciatic neuropathy must be differentiated from a lumbar compression radiculopathy, and this is often challenging. The latter can be considered a nerve compression syndrome. As disc herniation rarely involves several segments, neuropathy is first suspected when multiple segments are involved. When the straight-leg-raising test is made just short of pain, internal rotation of the femur increases pain and external rotation decreases pain in sciatic neuropathy but has little effect upon lumbar radiculopathies.

CLINICAL SIGNS

Note the comparative height of the iliac crests. If chronic sciatic neuralgia is on the high iliac crest side, degenerative disc weakening with posterolateral protrusion should be suspected. If occuring on the side of the low iliac crest, one must consider the possibility of a sacroiliac slip and lumbosacral torsion as being the causative factor. There is a lessening or lack of the deep tendon reflex in sciatica (Babinski's sciatica sign). When the patient's great toe on the affected side is flexed, pain will often be experienced in the gluteal region (Turny's sign). Also in sciatica, the pelvis tends to maintain a horizontal position despite any induced degree of scoliosis (Vanzetti's sign), unlike other conditions in which scoliosis occurs where the pelvis is tilted.

Lasegue's Straight-Leg-Raising Test. The patient lies supine with legs extended. The examiner places one hand under the heel of the affected side and the other hand is placed on the knee to prevent the knee from bending. With the limb extended, the examiner flexes the thigh on the pelvis keeping the knee straight. Normally, the patient will be able to have the limb extended to almost 90° without pain. If this maneuver is markedly limited by pain, the test is positive and suggests sciatica from lumbosacral or sacroiliac lesions, subluxation syndrome, hamstring tightness, disc lesions, spondylolisthesis adhesions, or IVF occlusion. Some examiners feel that pain at 30° indicates sacroiliac involvement; at 60°, lumbosacral disorder; 80°, L4-L5 problem. A second method of using this sign is to have the patient attempt to touch the floor with the fingers while the knees are held in extension during the standing position. Under these conditions, the knee of the affected side will be flex, the heel slightly elevate, and the body elevate more or less to the painful side. Many reports confirm that when Lasegue's sign is positive, the pupils will dilate, blood pressure will rise, and the pulse will become more rapid. These phenomena are not present in the malingerer or psychoneurotic individual.

Braggard's Test. If Lasegue's test is positive at a given point, the leg is lowered below this point and dorsiflexion of the foot is induced. The sign is negative if pain is not increased. A positive sign is a finding in sciatic neuritis, spinal cord tumors, IVD lesions, and spinal nerve irritations. A negative sign points to muscluar involvement such as tight hamstrings. Braggard's test helps to differentiate the pain of sciatic involvement from that of sacroiliac involvement as the sacroiliac articulation is not stressed by the Braggard maneuver, nor is the lumbosacral joint.

Fajersztajn's Test. When straight leg raising and dorsiflexion of the foot are performed on the asymptomatic side of a sciatic patient and this causes pain on the symptomatic side, there is a positive Fajersztajn's sign which is particularly indicative of a sciatic nerve root involvement such as a disc syndrome, dural root sleeve adhesions, or some other space-occupying lesion. This is sometimes called the well or cross-leg straight-leg-raising test.

Demianoff's Test. This is a variant of Lasegue's test used in lumbago and funiculitis with the intent of differentiating between lumbago and sciatica. When the affected limb is first extended and then flexed at the hip, the corresponding half of the body becomes lowered and with it the muscle fibers fixed to the lumbosacral segment. This act, which stretches the muscles, induces sharp lumbar pain. Lasegue's sign is thus negative as pain is caused by stretching the affected muscles at the posterior portion of the pelvis rather than stretching the sciatic nerve. To accomplish with the patient supine, the pelvis is fixed by the examiner's hand firmly placed on the anterior superior iliac spine, and the other hand elevates the leg on the same side. No pain results when the leg is raised to a 80° angle. When lumbago and sciatica are coexistent, Demianoff's sign is negative on the affected side but positive on the opposite side unless the pelvis is fixed. Demianoff's sign is also negative in bilateral sciatica with lumbago. The fixation of the pelvis prevents stretching the sciatic nerve, and any undue pain experienced is usually associated with ischiotrochanteric groove adhesions. This sign has been found to be valuable in determining local lesions of muscles, upper lumbar nerve roots, and funicular sciatica.

Belt Test. The standing male patient bends forward with the examiner holding the patient's belt at the back. If bending over without support is more painful than with support, it indicates a sacroiliac lesion. Conversely, if bending over with support is more painful than without support, it is indicative of lumbosacral or lumbar involvement.

Deyelle-May Test. This test is often helpful in differentiating the various etiologies of sciatic pain and particularly designed to differentiate between pain from pressure on the nerve or its roots and pain due to other mechanisms in the lower back. Compression or tractional pressure on muscles, ligaments, tendons, or bursae may cause reflex pain that often mimics actual direct nerve irritation. Usually, reflex pain does not follow the pattern of a specific nerve root, is more vague, does not cause sensory disturbances in the skin, comes and goes, but may be very intense. The procedure, in the sitting position, is to instruct the patient to sit very still and brace himself in the chair with his hands. The painful leg is passively extended until it causes pain, then lowered just below this point. The leg is then held by the examiner's knees and deep palpation is applied to the sciatic nerve high in the popliteal space which has been made taut by the maneuver. Severe pain indicates definite sciatic irritation or a root compression syndrome as opposed to other causes of back and leg pain such as the stretching of strained muscles and tendons or the movements of sprained articulations.

Minor's Sign. A patient with sciatica will arise from the seated position in a particular supporting position. If the chair has arms, both will be grasped and the trunk will be flexed forward. When arising, the elbows extend to push the trunk forward and upward, the hand on the uninvolved side will then be placed on the thigh, the other hand will be placed on the hip of the involved side, and the knee on the involved side will remain flexed to relieve the tension on the sciatic nerve. The knee on the uninvolved side is then extended to support the majority of body weight.

Buckling Sign. With the patient supine, the examiner slowly raises the involved lower limb (flexes it on the trunk) with the unsupported knee extended. A patient with radiculitis will automatically flex the knee to relieve the tension from the sciatic nerve.

Lindner's Sign. The patient is placed supine. A positive sign is found when conducting Brudzinski's test (progressive occiput, cervical, and upper thoracic flexion) if the patient's ipsilateral sciatic pain is reproduced or aggravated. It is indicative of lower lumbar radiculitis, as contrasted to the sharp but diffuse pain experienced in meningitis.

Sicard's Sign. A patient with sciatic-lke symptoms is placed in the supine position. The limb on the involved side is raised with the knee extended to the point of pain, then it is lowered about 5*, and the examiner firmly dorsiflexes the large toe. Because this will increase tension forces on the sciatic nerve, pain will be reproduced in the posterior leg and/or thigh in cases of sciatic neuritis.

Lewin's Punch Test. This test, which should be reserved for the young and muscular, is conducted with the patient in the relaxed standing position. If local pathology has been ruled out, a positive sign of lower lumbar radiculitis is seen when a sharp below to the ipsilateral buttock over the area of the belly of the piriformis elicits a sharp pain, but a similar blow to the contralateral buttock does not elicit pain.

Bonnet's Sign. A patient with sciatica is placed supine. The examiner lifts the involved limb slightly, adducts and internally rotates the thigh while maintaining the knee extended, and then continues to flex the thigh on the trunk to patient tolerance as in a SLR test. If this maneuver exaggerates the patient's pain or the pain response is sooner than that seen in Laseque's SLR test, sciatic neuritis, psoas irritation, or a hip lesion is indicated.

Lasegue's Differential Sign. This test is used to rule out hip disease. A patient with sciatic symptoms is placed supine. If pain is elicited on flexing the thigh on the trunk with the knee extended, but it is not produced when the thigh is flexed on the trunk with the knee relaxed (flexed), coxa pathology can be ruled out.

MANAGEMENT

As direct trauma to the nerve is so rare, careful evaluation of lumbar, sacral, and sacroiliac subluxations and fixations must be made, as well as lower back, pelvic, and hip musculature and trigger points. Corrective osseous adjustments, muscle techniques, and reflex techniques should be applied when indicated. Local heat and corrective muscle rehabilitation speed recovery when applied in the appropriate stage. Of all nerves in the body, the sciatic is one of the slowest to regenerate. The feet, upper cervical area, thoracolumbar junction, and overall posture should be evaluated for signs of predisposing defects in biomechanics.

Spinal Cord Injuries

Any trace of sensory abnormality, objective or subjective, should immediately raise suspicion of injury to the spinal cord or cauda equina. Injuries to the lumbosacral cord or its tail occur from vertebral fractures, dislocations, or penetrating wounds in severe accidents. In other rare instances, the cord may be damaged from violent falls with trunk flexion. The T12-L1 and L5-S1 areas are the common sites of injury, especially those of crushing fractures with cord compression. Neurologic symptoms develop rapidly, but the lower the injury, the fewer roots will be involved. More common than these rare occurrences are cord tractions, concussions, and less frequent contusions.

Traction of the Spinal Cord. A scoliotic deviation must always be attended by a commensurate vertebral body rotation to the convex side. If this does not occur, it is atypical and most likely pain producing. If the vertebral bodies were not subject to the law of rotation during bending, the spine would have to lengthen during bending and its contents (ie, cord, cauda equina, and their coverings) would be subjected to considerable stretch. Thus, in a case of scoliotic deviation in the lumbar area without body rotation towards the convex side, seek signs indicating undue tension within the vertebral canal. It should also be noted that atlanto-occipital, atlanto-axial, and coccyx disrelation with partial fixation places a degree of traction upon the cord, dura, and dural sleeves in flexion-extension and lateral bending efforts.

Concussion of the Spinal Cord. Immediate signs are usually not manifested in mild or moderate injuries; but weeks later, lower extremity weakness and stiffness may be experienced. It takes time for the nerve fibers to degenerate. Deep reflexes become exaggerated, and originally mild sensory, bladder, and rectal disurbances progress. The picture is cloudy, often mimiking a number of cord diseases (eg, sclerosis, atrophy, syringomyelia). Life is rarely threatened, but full recovery is doubtful.

Contusions of the Spinal Cord. Cord concussion usually complicates cord contusion. If laceration occurs, shock is rapid. Deep reflexes, sensation, and sphincter control are lost. The paralysis is flaccid. Obviously, a prognosis cannot be made until the shock is survived.

Kernig's Test. The supine patient is asked to place both hands behind his head and forcibly flex his head toward his chest. Pain in either the neck, lower back, or down the lower extremities indicates meningeal irritation, nerve root involvement, or irritation of the dural coverings of the nerve root. A variation of this test is also attributed to Kernig: The examiner flexes the thigh at a right angle with the torso and holds it there with one hand. With the other hand, the ankle is grasped and an attempt is made to extend the leg at the knee. If pain or resistance is encountered as the leg extends, the sign is positive provided there is no joint stiffness or sacroiliac disorder. Milgram's Test. Ask the supine patient to keep his knees straight and lift both legs off the table about 2 inches and to hold this position for as long as possible. The test stretches the anterior abdominal and iliopsoas muscles and increases intrathecal pressure. Intrathecal pressure can be ruled out if the patient can hold this position for 30 seconds without pain. If this position cannot be held or if pain is experienced during the test, a positive sign is offered indicating intrathecal pathology, herniated disc, or pressure upon the cord from some source.

Intervertebral Disc Syndrome

It is generally agreed that a true diagnosis of disc herniation with or without fragmentation of the nucleus pulposus can only be made on surgical intervention. Thus the term "intervertebral disc syndrome" is generally used when conservative diagnostic means are used exclusively. There is considerable dogmatism associated with both diagnosis and management.

The terms protrusion, rupture, and herniation are often used to describe the pathologic grade of an IVD lesion. However, to establish a practical guideline in the management of such lesions, many physicians refer to a Grade I, II, or III disc syndrome based primarily on symptomatology.

CLASSES

In a Grade I syndrome, the patient has intermittent pain and spasm with local tenderness. There is very little or no root compression. Paresthesia and/or radiculitis may extend to the ischium.

In a Grade II syndrome, some nerve root compression exists along with pain, sensory disturbance, and occassionally some atrophy. Paresthesia and/or radiculitis may extend to the knee.

In a Grade III syndrome, there is marked demonstrable muscle weakness, pronounced atrophy, and intractable radicular pain. Paresthesia and/or radiculitis may extend to the ankle or foot.

Beyond these three grades, we find frank herniation. In rupture, there is a complete extrusion of the nucleus through the annulus into the canal or IVF. All the above symptoms are found in herniation, and, in addition, pain is worse at night and not generally relieved by most conservative therapies.

The IVD syndrome usually has a traumatic origin and occurs more commonly between the ages of 20 and 60. There may be a history of low back complaints with evidence of organic or structural disease. Most protrusions seen in athletes occur at the L4-L5 or L5-S1 level, involving the L4, L5, or S1 roots. A unilateral sciatic pain following a specific dermatome segmentation and not remissive except by a possible position of relief is often presented. There is usually a C scoliosis away from the side of pain, splinting, and a flattening of the lumbar spine. Lasegue's, Kemp's, and Nafzigger's tests are positive. There may be diminished tendon reflexes of the involved segment and possible weakness and/or atrophy of the musculature innervated.

Lasegue's Rebound Test. At the conclusion of a positive sign during the straight-leg-raising test, the examiner may permit the leg to drop to a pillow without warning. If this rebound test causes a marked increase in pain and muscle spasm, then a disc involvement is suspect.

OTHER CLINICAL SIGNS

A number of helpful neurologic and orthopedic procedures have been developed to aid the diagnosis and differentiation of IVD lesions. See Table 25.2.

Bechterew's Test. The patient in the seated position is asked to extend first one knee with the leg straight forward (parallel to the floor). If this is performed, the patient is asked to extend the other knee likewise. If this can be performed, the patient is asked to extend both limbs simultaneously. If the patient is unable to perform any of these tests because of sciatic pain or able only by leaning far backward to relieve the tension on the sciatic nerve, a lumbar disc disorder or acute lumbosacral sprain should be suspected.

Dejerine's Sign. If sneezing, coughing, and straining at the stool (Dejerine's triad) or some other Valsalva maneuver produces or increases a severe low back or radiating sciatic pain, a positive Dejerine's sign is present. This is indicative of some disorder that is aggravated by increased intrathecal pressure (eg, IVD lesion, cord tumor, etc).

Astrom's Suspension Test. This is a confirmatory test for sciatic neuritis and/or lumbar traction therapy. The patient is asked to step on a low stool, grasp a horizontal bar, and hang suspended for several seconds. In most cases, the traction effect produced will be sufficient enough to retract a protruding disc, separated the articular facets, open the IVFs, and, thus, relieve the patient's discomfort. A variation of this test is for the examiner to conduct a spinal percussion test while the patient is suspended.

Also see Beery's sign, Goldthwait's test, Neri's bowing sign, Lewin's supine test, Brudzinski's test, and Naffziger's test.

ROENTGENOGRAPHIC CONSIDERATIONS

Normally, as a major adaptive change to the carrying of weight, there is a flattening of the lumbar lordosis and a mild rotation of the sacrum into a more vertical position. The maximum adaptation occurs at the lumbosacral junction with only minor adjustments at the higher levels. The L5 disc assumes a more nearly horizontal position with widening posteriorly and compression anteriorly, which results in a decrease in the downward sliding force applied at the S1 level. These reflections by Olsen go on to state that the usual manifestion of disordered function of any part of the motor unit is weakness. He quotes DeJarnette's 1967 notes that "The position of the sacral base is often compensatory to keep severe situations from becoming worse through weight bearing".

When an IVD leaves its normal anatomic position, routine radiographic examination without contrast medium may present diagnostic characteristics such as narrowing of the intervertebral space (most typical), retrolisthesis of the vertebral body superior to the herniated disc, posterior osteophytes on the side of the direction of the herniated disc or apophyseal arthrosis, and sclerosis of the vertebral plates as a result of stress on "denuded" bone (frequent). Malformations as asymmetric transitional lumbosacral vertebra and spina bifida are seen more frequently with herniated disc than in cases in which such anomalies do not exist. Scoliosis is more common in the L4-L5 disc than in the L5-S1 disc.

Three functional views should be taken in the erect position: A-P neutral and right and left maximum lateral flexion. Points to especially evaluate are asymmetry and unilateral elevation of disc spaces, limited and impaired mobility on the affected side, blocked mobility contralaterally one segment above the L5-S1 level, and slight rotation of the L4 or L5 vertebral body toward the side of collapse. Abnormal findings suggesting a fixed prolapse in these functional views include flattening of the lumbar curve, posterior shifting of one or more lumbar vertebral bodies, impaired mobility on forward flexion so that the disc space does not change as compared to the findings in the neutral position, and impaired mobility on dorsiflexion.

MANAGEMENT

The cause of pain may vary from a mild bulge, to a severe protrusion, to frank prolapse and rupture of the IVD into the vertebral canal. While physical signs are helpful, but not conclusive, in determining the extent of damage, subjective symptoms are often misleading.

Cryotherapy and other forms of pain control are advisable during the acute stage for 48 hours. Some relief will be achieved by placing the patient prone with a small roll under the lower abdomen to flex the lumbar spine while applying manual traction techniques. This should be followed by corrective adjustments to correct attending fixations and abnormal biomechanics, traction, and other physiotherapy modalities. A regimen of therapeutic exercises to improve torso strength, a temporary lumbopelvic support, and shoe inserts designed to improve postural balance and lessen gait shock are extremely helpful during recuperation.

Adams' sign Goldthwait's test Milgram's test Astrom's suspension Gower's sign Minor's sign test Hyperextension Muscle strength grading Babinski's sciatic tests Naffziger's test sign Kemp's test Neri's bowing sign Bechterew's test Kernig's sign Range of motion tests Beery's sign Lasegue's rebound Tendon reflexes Bowstring sign test Turyn's sign Bragard's test Lasegue's SLR test Vanzetti's sign Dejerine's sign Lewin's supine test Deyerle-May's test Light touch/ Fajersztajn's test pain tests

Spondylolisthesis

The anterior or posterior sliding of one vertebral body on another (spondylolisthesis) can result from either traumatic pars defects or degenerative disease of the facets. There is a separation of the pars interarticularis which allows the vertebral body to slip forward, carrying with it a portion of the neural arch. Davis points out that many authorities consider the condition as congenital, while others are of the opinion that trauma in early childhood is more often responsible. Regardless, when witnessed in an adult, the lesion dates from childhood rather than from some recent injury. Rehberger states it occurs in 4%-6% of people, but is present in about 25% of people complaining of constant backache.

BACKGROUND

An increase in the S1 sagittal diameter in spondylolisthesis occurs during teen maturation. Displacement tends to increase before the age of 30, but this trend sharply decreases thereafter unless there is an unusual cause such as chornic fatigue coupled with an unusual prolonged posture.

Predisposing spinal instability is frequently related to a degenerated disc at the spondylolisthetic level. Quite often the lesion is asymptomatic during the first 2 decades of life. Dimpling of the skin above the level of the spondylolisthesis may be observed or extra skin folds may be seen because of the altered spinal alignment. When the condition does become symptomatic, the pain is usually recurrent and increases in severity with subsequent episodes. Low back pain often develops after insignificant injury or strain, with recurrent pain gradually increasing in intensity. Weakness, fatigue, stiffness, unilateral or bilateral sciatic pain, and extreme tenderness in the area of the spinous process of L5 are associated. Pain usually subsides in the supine position.

ROENTGENOGRAPHIC CONSIDERATIONS

Disc tone is best analyzed through neutral, flexion, and extension views. As with spondylolysis, the most common site of spondylolisthesis is in the lower spine, but it has been reported in all areas of the lumbar spine and the cervical area. The typical situation is slippage of L5 on the sacral base (75% to 80%), but it is occasionally seen at the L4 segment.

Spondylolisthesis is graded by dividing the sacral base or the superior end plate of L5 into four equal parts when viewed in the lateral film: the Meyerding method. The part occupied by the posterior-inferior tip of the vertebra above indicates the degree of forward slip. In suspected cases where no obvious gross slippage has occurred, the Meschan method is used on the lateral projection. A line is drawn across the posterior, superior, and inferior tip of the L5 vertebral body. A second line is drawn from the posterior-superior tip of the sacrum to the posterior-inferior tip of L4. Normally, these lines should overlap or nearly so. If they are parallel or form an angular wedge at the superior, it indicates an anterior movement of L5. If the angle formed is greater than 2° or if the lines are parallel and separated more than 3 mm, a spondylolisthesis is present. To determine the degree of instability, flexion and extension studies in the lateral projection are utilized. The degree of angulation formed in flexion is subtracted from the degree of angulation formed in extension, as the maximum degree of slippage is seen during extension. The result of these two measurements offers the degree of instability present.

Oblique views show a defect in the isthmus or pars interarticularis where the neural arch is visualized as a picture of a terrier's head. The pedicle and transverse process form the head of the dog, the ears by the superior articular process, the neck by the pars interarticularis, the body by the lamina, and front legs by the inferior articular process. When the defect appears as a collar on the dog, a spondylolysis is present. If the terrier is decapitated, a spondylolisthesis is present.

Other roentgenographic findings include an unusual lumbar lordosis with increased lumbosacral angle and overriding of facets adjacent to the defect which is usually visible on the A-P view. In time, the overriding apophyseal joints show osteoarthritic changes. The amphiarthroidial joint between the vertebral bodies frequently shows narrowing, spurring, and associated osteoarthritic changes. A lumbar kyphosis is rarely seen, indicating the possibility of a herniated disc.

MANAGEMENT

Symptoms progress from mild stiffness and low-back spasm after working or lifting in the forward flexion position to a sharp pain upon mild hyperextension of the trunk. Pain elicited by spinal percussion exhibits late, but depression of the spinous process is an early physical sign.

Cryotherapy and other forms of pain control are advisable during the acute stage (eg, 48 hours). Considerable relief will be achieved by placing the patient prone with a small roll under the lower abdomen to flex the lumbar spine while applying manual traction techniques. This should be followed by corrective adjustments to release attending fixations, improve abnormal biomechanics, and help reduce the separation. Traction and other physiotherapy modalities are helpful adjuncts. A regimen of mild stretching exercises, with emphasis on flexion, is extremely helpful during recuperation. Sole lifts or lowered heels may be necessary if the sacral angle is abnormally wide. Lifting should be prohibited until the patient is unsymptomatic for several weeks, and then initiated only with caution.

Lumbar Spondylolysis

Spondylolysis is similar to spondylolisthesis in that there is also a defect in the pars interarticularis, but there is no anterior slipping of the vertebral body. Disc narrowing and facet sclerosis are frequently associated. It is a degenerative condition of early middle life, more common to males and often associated with athletic or occupational stress. The most common site of spondylolysis is in the lower spine.

In describing spondylolysis, Davis reminds us that the term "pre-spondylolisthesis" is a misnomer as it indicates that spondylolisthesis will occur. This term is also inaccurate to describe an exaggeration of the sacral base angle. It is true that spondylolysis will contribute to spinal instability much the same as an exaggerated sacral base angle, but it is not true that spondylolisthesis will result in either condition. Degenerative arthropathy of the apophyseal joints will most likely result from the stress and strain placed upon the facets. The defective arrangement will also predispose the individual to spinal fatigue. The condition is also referred to as hypertrophic osteoarthritis, this is also a misnomer as there is no inflammatory involvement present. The appropriate nomenclature is discogenic spondylosis.

There is a high incidence of trauma and strenuous physical activity in the history of spondylolysis. Incidence in sports is particularly high in fast bowlers, affecting the contralateral side of the active arm. It is common in the obese, robust, endomorphic individual such as heavy boxers and professional wrestlers. It is not uncommon in oarsmen. A large number of college and professional football interior linemen present low-back pain with abnormalities present on radiographs. A large percentage of such cases show a degree of spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis, usually with normal neurologic signs. Because of chronic lumbar stress, weight lifting is also commonly associated with an increased incidence in spondylolysis and disc herniation at the lower lumbar area. Rarely, vertebral-body fracture is associated.

Roentgenographic Considerations. Turner describes the process as primary change in the IVD with progressive loss of turgor and elasticity contributing to softening and weakening of the disc margin. Marginal spurring, lipping, and the consequence of osteophytic formation ensues. The sacroiliac areas are not usually involved. Narrowing of one or more IVD spaces may develop when the disc space together with changes in the curvature of the spine appear narrowed. The clinical picture, associated with spondylosis deformans, is usually referred to the area of structural deformity that results in compromise of contour and diameter of the related IVF. Oblique views, along with standard A-P and lateral views, are helpful in showing defects or fractures of the pars interarticularis. Not infrequently, cephalad-angled views or tomograms are necessary.

Management of Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis. Mild and moderate cases respond well to chiropractic anterior lumbar techniques. Adjunctive care includes low back traction in selected cases, positive galvanism, ultrasound, and alternating contractile currents to improve muscle tone. Immobilization using a lumbosacral support helps in the more advanced cases. Once the disorder becomes asymptomatic, corrective exercises should be recommended to maintain optimal muscle tone.

Prognosis. Prognosis is good in firstand second-degree types with minimal neurologic symptoms. If conservative measures fail, surgical fusion and removal of the neural arch is recommended. Prognosis is good in cases of minimal separation but poor in cases of gross separation where the patient is usually left with a residual rigidity and stiffness in the lower spine.

Subluxations, Fractures, and Dislocations

Subluxations are discussed throughout this chapter, but a few general points should be made here. The apices of curvatures and rotations are logical points for spinal listings since they are frequently the location of maximum vertebral stress. Subluxations may occur at other points in curves and rotations, particularly at the beginning point of a primary defect in balance such as in the lower lumbar and upper cervical sections. Subluxations also frequently occur at the point where a primary curve merges into its compensatory curve. A posterior L3 is rare when the apex of the lumbar curve is too high or too low, but common at L4, L5, or the sacral base. When the apex of the lumbar curve is too low, a posterior subluxation will most likely be found in the upper lumbar area.

ROENTGENOGRAPHIC CONSIDERATIONS

As in other areas of the body, x-ray views of the spine must be chosen according to the part being examined and the injury situation. And as with the cervical spine, careful evaluation must be made of the vertebral structures, the IVDs and paraspinal soft tissues. The L5-S1 and sacroiliac joints, the pelvis, and its contents deserve careful scrutiny. Acute injuries to the supporting soft tissues about a vertebra are rarely demonstrable. Their presence is suggested when the normal relations of bony structures are disturbed. However, when ligamentous lesions heal, hypertrophic spurs and sometimes bridges may develop locally on the margins of the bones affected.

The lower back and pelvis are the most common sites for avulsion-type injuries. Severe, sudden muscle contraction can produce fragmented osseous tears near sites of origin and insertion. Avulsions in the lumbar area often occur with transverse-process fragmentation at the site of psoas insertion. Although the transverse processes of the lumbar spine are quite sturdy, multiple fractures are seen in some football injuries. Lumbar transverse-process fractures are sometimes not evident or are poorly visualized in roentgenography unless markedly displaced or angulated due to overlying gas and/or soft-tissue shadows which obscure detail. Howe suggests a cleansing enema or other means of clearing over lying soft-tissue shadows whenever all bony processes are not well visualized. Transverse-process fractures are frequently asymptomatic or nearly so and lack the symptoms to encourage a most careful examination.

Miscellaneous Pathologic Signs

Romberg's Station Test. During this test, the examiner must stand close to the patient in the event the patient's loses balance. The patient is asked to stand in a relaxed position and to close the eyes. If this cannot be accomplished without falling or severe swaying that requires the feet to be moved to regain balance, a positive sign is established that rules out cerebellar or labyrinthine disease. A positive sign is seen in locomotor ataxis associated with marked alcoholic neuritis, spinocerebellar tract disease, and in pernicious anemia when the columns of Goll and Burdach are affected. While a patient with cerebellar or labyrinthine disease may have difficulty standing, the position is usually taken equally well with or without visual support.

Neri's Test. The patient is placed supine with the knees extended. The examiner flexes the involved thigh on the trunk to approximately 45° while keeping the knee extended, as in a SLR test. Normally, the contralateral limb will remain fairly flat against the table. In organic hemiplegia, however, the opposite limb will flex at the knee.

Barre's Sign. The patient is placed in the prone position with the knees passively flexed at right angles to the thigh by the examiner. If the patient cannot actively hold this position with either or both limbs, it is a positive sign of pyramidal tract disease.