|

Chapter 6:

Radiologic Manifestations of Spinal Subluxations

From R. C. Schafer, DC, PhD, FICC's best-selling book:

“Basic Chiropractic Procedural Manual”

All of Dr. Schafer's books are now available on CDs, with all proceeds being donated |

Spinal Subluxations

Definition and Significance

Radiologic Manifestations

Terminology of Radiologic Manifestations of Subluxations

Static Intersegmental Subluxations

Kinetic Intersegmental Subluxations

Sectional Subluxations

Paravertebral Subluxations

Classification of Radiologic Manifestations

Static Intersegmental Subluxations

Kinetic Intersegmental Subluxations

Sectional Subluxations

Extraspinal Subluxations

Case Presentations

Case Illustrating Classifications A-I and C-3

Case Illustrating Classifications A-I and R-2

Case Illustrating Classifications A-2, A-3, A-8, C-1, and C-2

Case Illustrating Classifications A-2, A-6, A-9, and C-1

Case Illustrating Classification A-3

Case Illustrating Classifications A-3, C-3, C-4, and D-1

Case Illustrating Classification A-3

Case Illustrating Classification A-4

Case Illustrating Classifications A-4 and C-2

Case Illustrating Classification A-5 (Spondylolisthesis)

Case Illustrating Classifications A-5, A-6, A-8 and A-9

Case Illustrating Classification A-7

Case Illustrating Classifications A-1, A-3, A-4, A-7, and A-8

Case Illustrating Classification A-8

Case Illustrating Classifications A-1, A-3, A-4, A-8, and A-9

Case Illustrating Classifications B-1, C-2, C-4, A-8, and A-9

Case Illustrating Classifications C-1, A-1, A-3, and A-8

Case Illustrating Classification C-1 and A-1

Case Illustrating Classifications C-2 and A-3

Case Illustrating Classifications C-4 and B-1

Through the years, there have been several concepts within the chiropractic profession about what actually constitutes a subluxation. Each has had its rationale (anatomical, neurologic, or kinematic), and each has had certain validity contributing to our understanding of this complex phenomenon.

Note: In years past, what is referred to above as a motion unit was called

a motor unit. The term motion unit was incorporated into chiropractic

terminology in the late 1970s to avoid confusion with the neurologic term

motor unit, meaning a single motor neuron and the muscle fibers its

branches innervate.

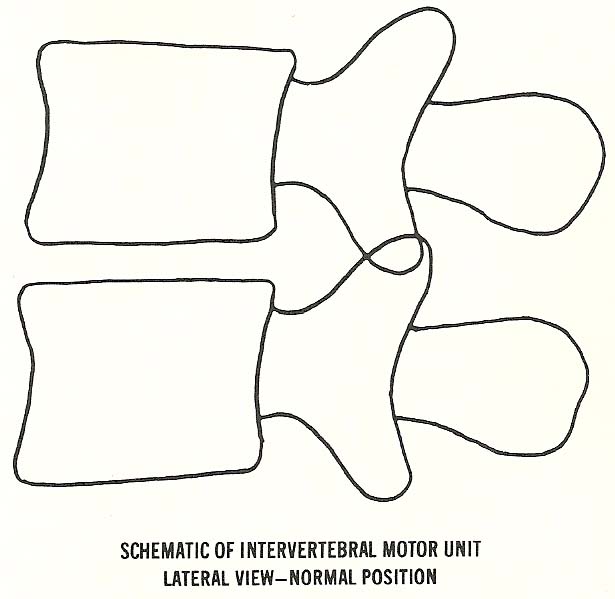

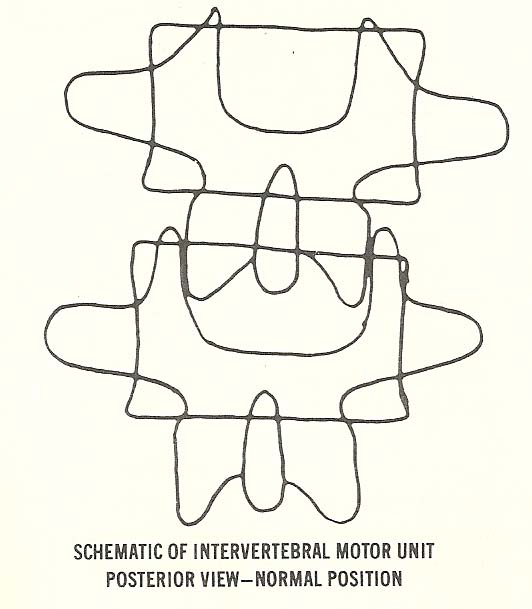

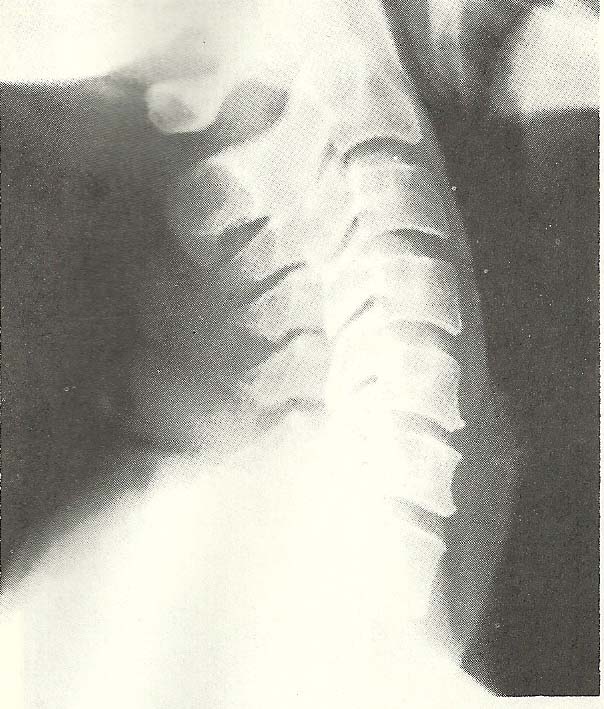

The method used for classifying roentgenographic manifestations of

subluxation is based on the concept of the intervertebral motion unit. An

intervertebral motion unit consists of two vertebrae and their contiguous

structures (disc interface and two posterior apophyses) forming a set of three

articulations at one intervertebral level. It is best illustrated by using a

lateral view (Figs. 6.1 and 6.2).

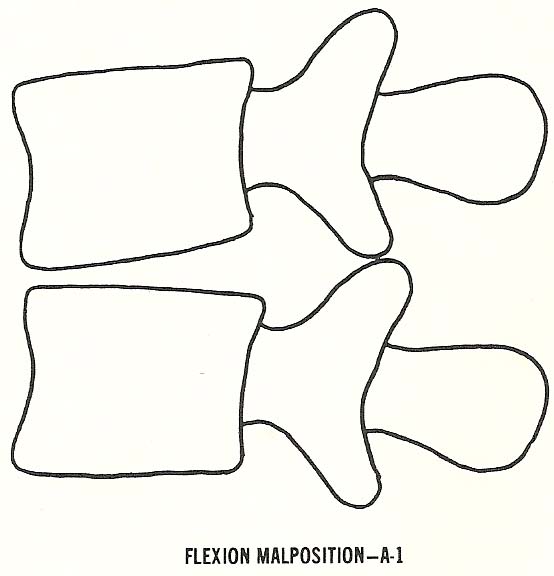

A-1. Flexion malposition.

Kinetic Intersegmental Subluxations

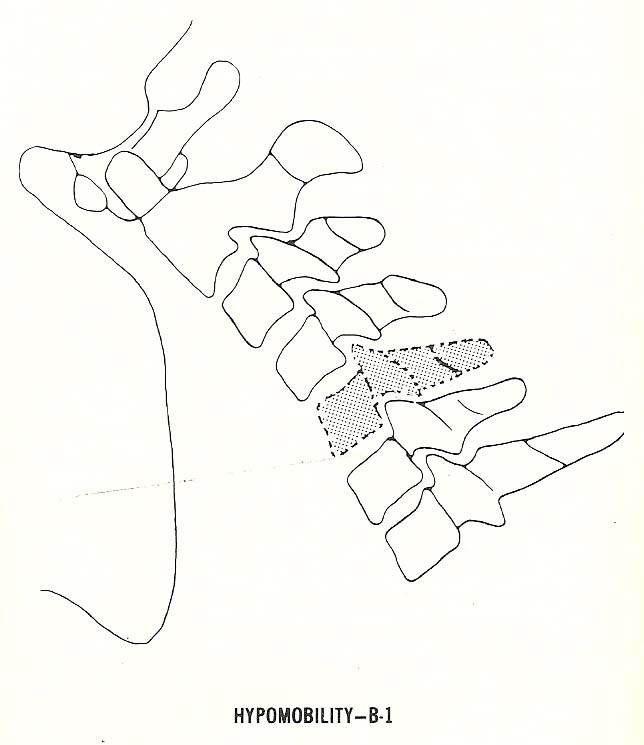

B-1. Hypomobility (fixation subluxation).

Sectional Subluxations

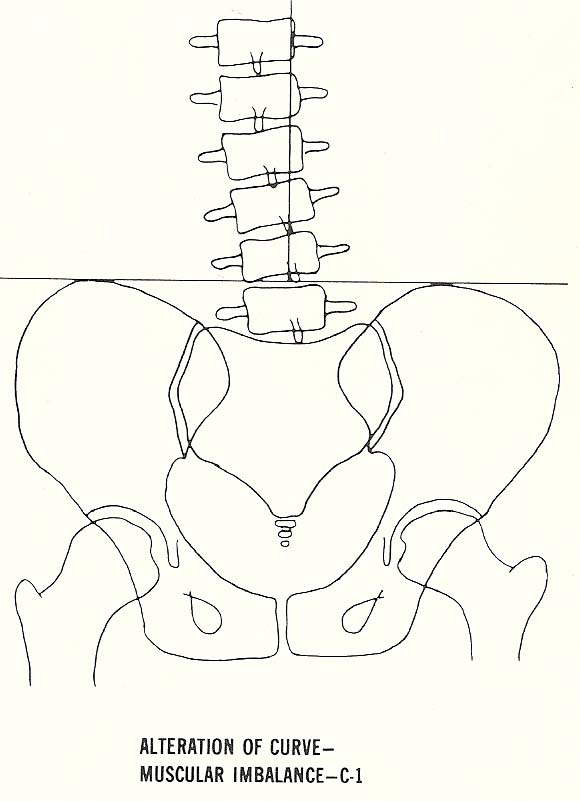

C-1. Scoliosis and/or alteration of curves secondary to musculature imbalance.

Paravertebral Subluxations

D-1. Costovertebral and costotransverse disrelationships.

Flexion Malposition. In flexion subluxation, there is wedging of the disc

space anteriorly as the vertebral bodies somewhat approximate one another

anteriorly (Fig. 6.3).

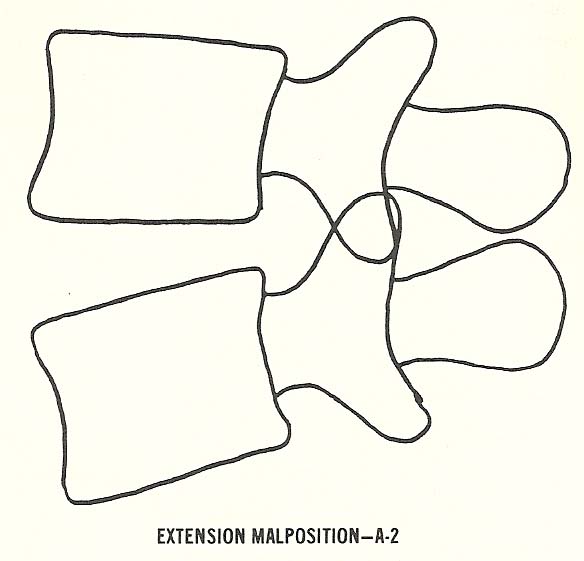

Extension Malposition. In this type of subluxation, which is one of the

most commonly encountered (especially in the low back), the vertebral bodies

approximate posteriorly and thus the disc narrows posteriorly (Fig. 6.4).

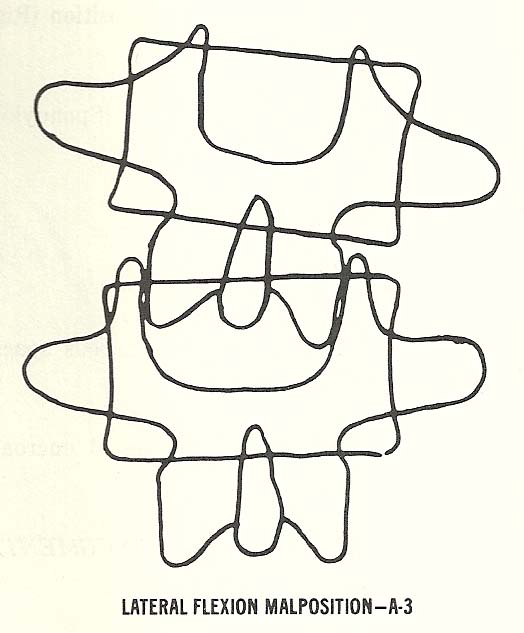

Lateral Flexion Malposition. This subluxation is characterized by lateral

wedging of the disc interspace produced by approximation of the vertebral bodies on the side toward which the vertebra above laterally flexes (Figs. 6.5 and 6.6).

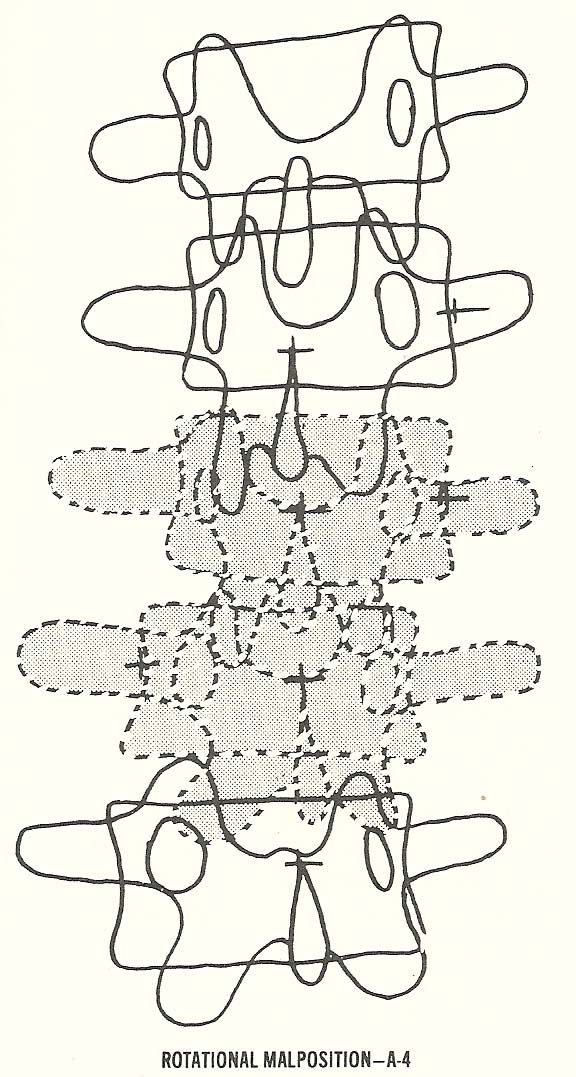

Rotational Malposition. Intervertebral rotation, even in subluxation, is

extremely limited at any single intervertebral level except in the upper

cervical spine. Thus, there are usually several segments involved in a

rotational disrelationship (Fig. 6.7).

Chapter 6: Radiologic Manifestations of Spinal Subluxations

This chapter describes the radiologic signs that may be expected when spinal subluxations are demonstrable by radiography.

SPINAL SUBLUXATIONS

Articular disorders of the spine are not always demonstrable by roentgenography, and to depict them radiographically often requires techniques other than those routinely used in spinal radiography (spinography). The

radiologic manifestations of spinal subluxation described in this chapter are

an attempt to provide a uniform classification of manifestations that may be

found when there is radiologic evidence of the presence of subluxation.

Admittedly, there are other classifications and concepts. Those chosen were

selected because they were believed to be defensible, widely acceptable, and

relatively easy to understand.

A motion unit has an anterior and posterior portion, and each has peculiar

and special characteristics. The articulations are the mobile portions of the

unit. This is mentioned because of the tendency to speak of a "subluxated

vertebra" when in fact it is the articulations that subluxate.

The anterior portion of the motion unit includes the vertebral bodies, the

interposed disc, the anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments (which are

not truly visible on a radiograph), and, of course, the muscles and other soft

tissues not radiographically visible. The function of the anterior portion of

the motion unit is essentially weight bearing and supportive. It has little

sensory innervation. Changes or pathology affecting these structures, while

they may be quite spectacular in appearance on a radiograph and alter spinal

biomechanics significantly, are seldom accompanied by severe subjective

discomfort in the local area.

The posterior aspect of a motion unit consists of the pedicles, neural

foramina, articular processes and apophyseal articulations, the ligamenta

flava, apophyseal capsules, the laminae, spinous processes, the inter- and

supra-spinous ligaments, and all the muscles and other attached soft-tissue

structures. Many of the posterior elements of a motion unit are richly endowed

with sensory and proprioceptive innervation. Therefore, problems, pathologies,

stresses, and distortions affecting these structures are typically painful.

The following sections explain and illustrate the consensus statement

regarding subluxation from the historic Houston Conference of Chiropractic

that was held in November of 1972.

Definition and Significance

A subluxation is the alteration of the normal dynamics and anatomical or

physiologic relationships of contiguous articular structures. In evaluating

this complex phenomenon, we find that it has or may have biomechanical,

pathophysiologic, clinical, radiologic, and other manifestations. Subluxations

are of clinical significance as they are affected by or evoke abnormal

physiologic responses in neuromusculoskeletal structures and/or other body

systems.

Radiologic Manifestations

In considering the possible radiologic manifestations of subluxations, it

should be emphasized that clinical judgment is necessary to determine the

advisability of exposing a patient to the potential hazards of ionizing

radiation. An important purpose of exposure, in addition to the evaluation of

subluxations, is the determination of other pathologies.

Radiographic procedures necessary to determine possible fractures,

malignancies, etc, may not be the specific views needed to evaluate the

possible radiologic manifestations of subluxation. When subluxation can be

evaluated by other clinical means, it may be prudent to avoid radiation

exposure.

Terminology of Radiologic Manifestations of Subluxations

Static Intersegmental Subluxations

A-2. Extension malposition.

A-3. Lateral flexion malposition (right or left).

A-4. Rotational malposition (right or left).

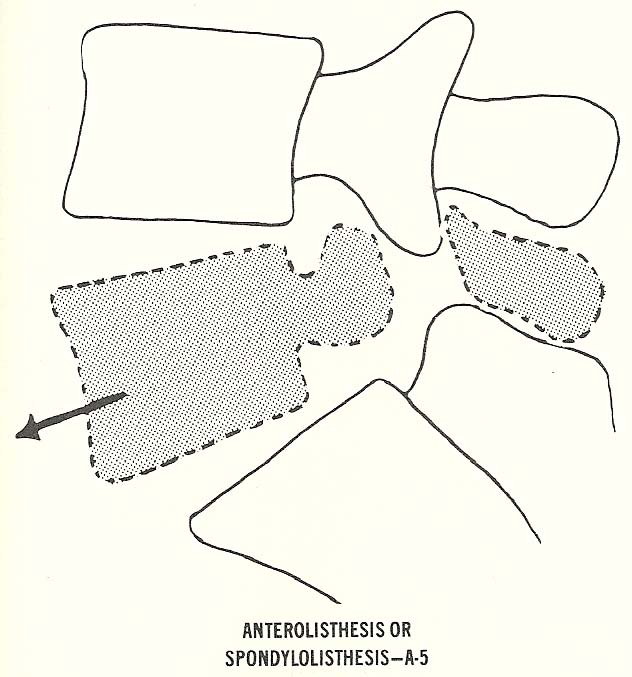

A-5. Anterolisthesis (spondylolisthesis).

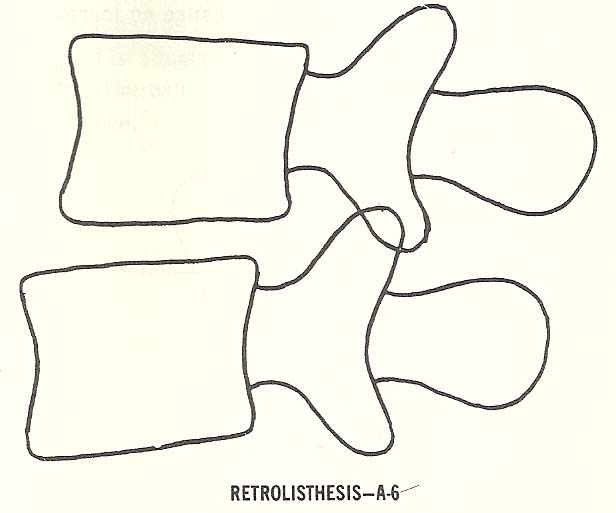

A-6. Retrolisthesis.

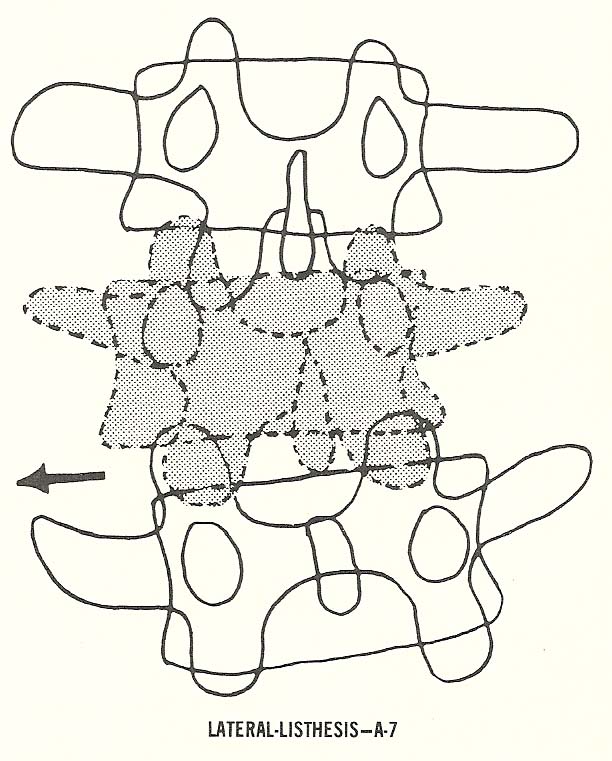

A-7. Laterolisthesis.

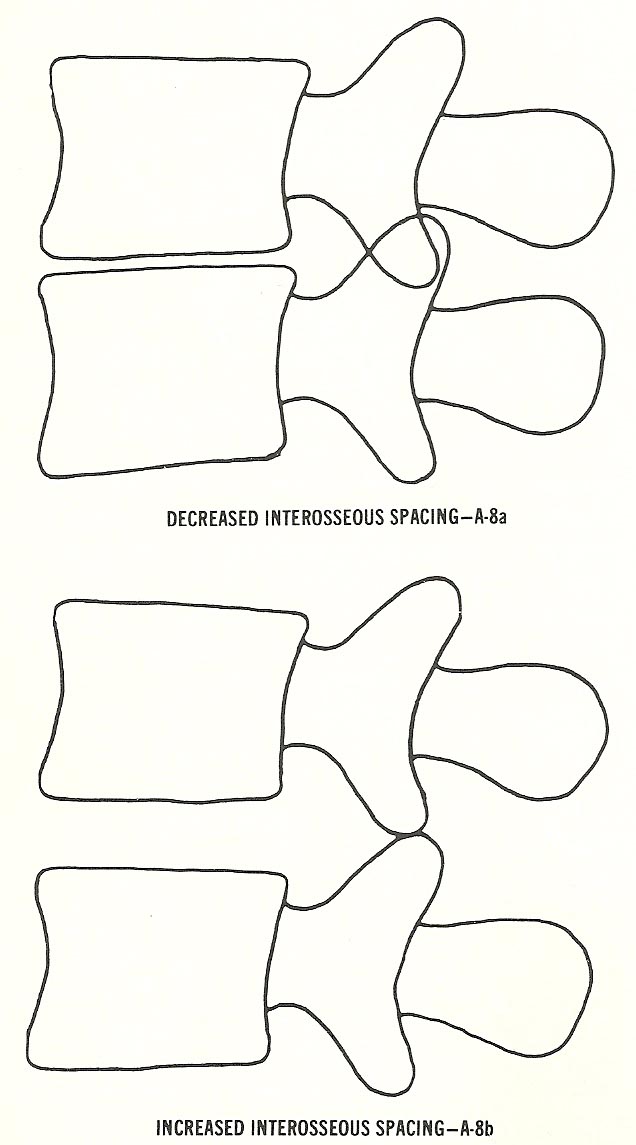

A-8. Altered interosseous spacing (decreased or increased).

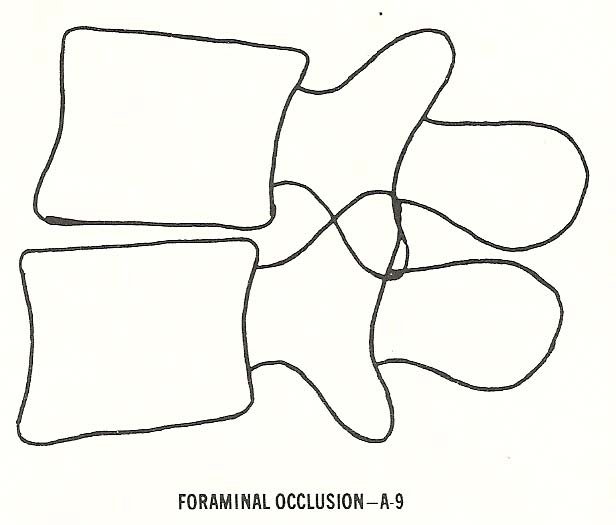

A-9. Osseous foraminal encroachments.

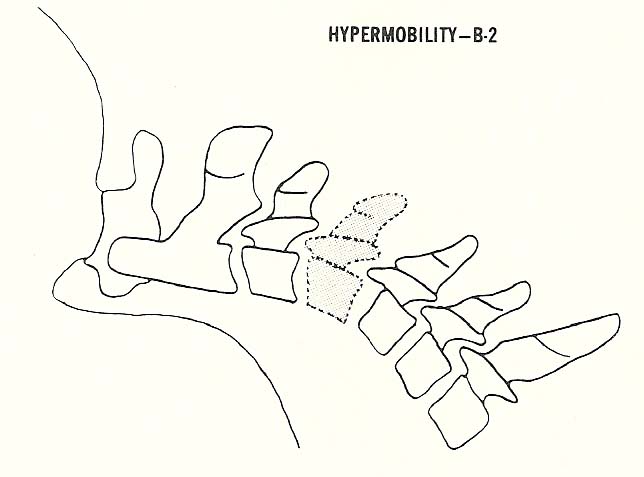

B-2. Hypermobility (loosened vertebral motion unit.

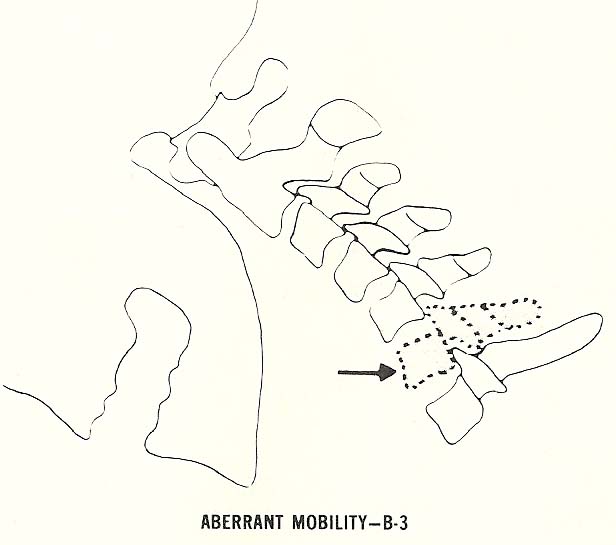

B-3. Aberrant motion.

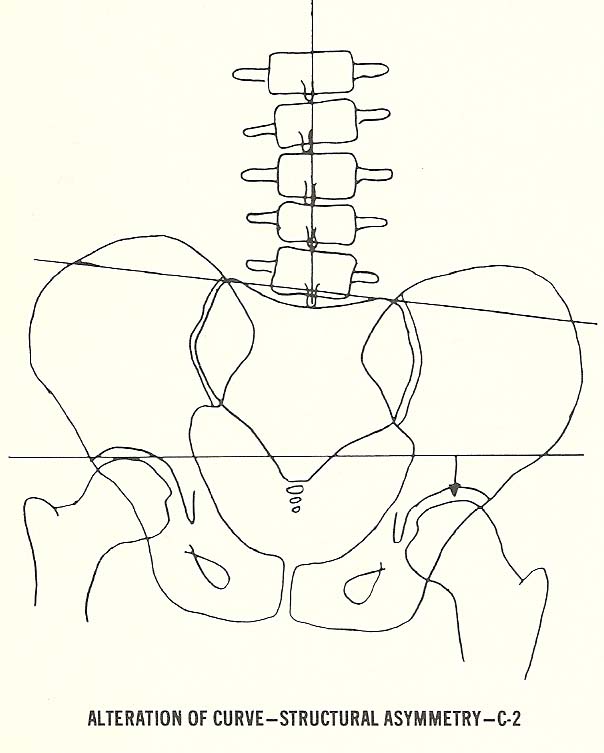

C-2. Scoliosis and/or alteration of curves secondary to structural

asymmetries.

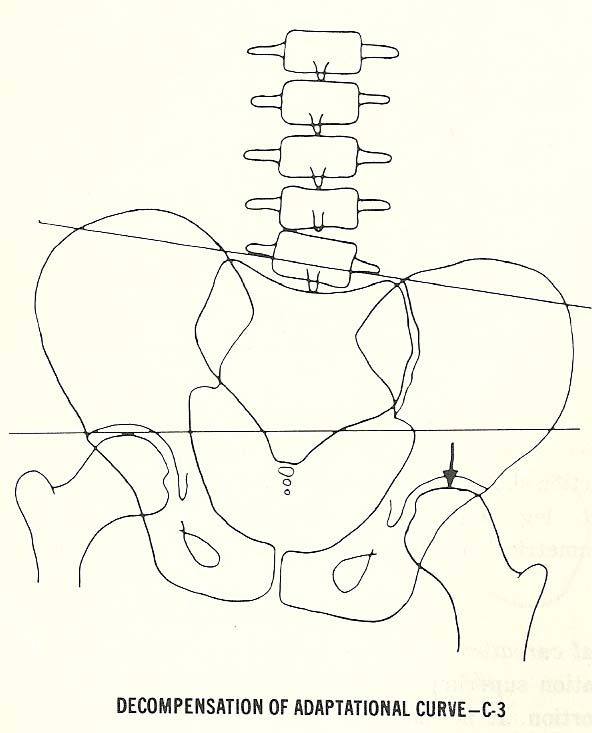

C-3. Decompensation of adaptational curvatures.

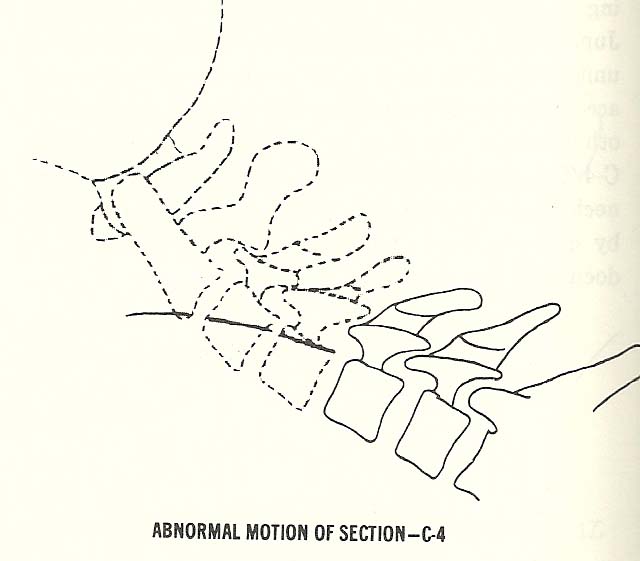

C-4. Abnormalities of motion.

D-2. Sacroiliac subluxations.

Note: The code names (eg, A-1, B-2, C-3, or D-2) listed above are rarely used in professional communications. A descriptive title is used such as "flexion malposition of C5," rather than "A-1 C5." ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Classification of Radiologic Manifestations

Static Intersegmental Subluxations

Because of this, the spinous processes separate (open)

and the inferior articular processes of the vertebra above glide upward upon

the superior articular processes of the vertebra below. This elongates the

intervertebral foramen (IVFs) so they appear larger in their vertical

dimension.

The

posterior articulations show radiographic imbrication as the inferior

articular processes of the vertebra above glide downward relative to the

superior articular processes of the vertebra below. As the motion unit

extends, the IVFs of the unit appear to become smaller in their vertical

dimension.

This also causes the facet articulation on the side of disc

narrowing to imbricate while the contralateral articulation shows separation

(opening) of the articular processes as the inferior articular process of the

upper vertebra glides upward on the apposing process of the lower segment.

dimension.

The preponderance of the body of a

rotated vertebra relative to its spinous process on the side toward which the

vertebra has rotated posteriorly is well known to all doctors of chiropractic.

A line drawing taken from an actual radiograph will show reverse rotation

between the vertebrae that can be portrayed by a dotted line with the top

three and the lower two vertebrae rotated in corresponding relationship to one

another.

The next three types of subluxation are those in which the suffix

"listhesis" is used. This suffix means "slippage," and the displacement is

usually a gross distortion.

|

Anterolisthesis or Spondylolisthesis. This malposition is typically

produced by interruption of the isthmus (usually congenital) of a displaced

vertebra at its pars interarticularis. |

|

|

|

Retrolisthesis. Posterior malpositioning of the upper segment of two

vertebrae set (motion unit) is known as retrolisthesis. |

|

|

|

Laterolisthesis. The lateral slipping characteristic of this type

subluxation is typically accompanied by considerable segmental rotation. |

|

|

|

Altered Interosseous Spacing. This form is probably the most common of all

subluxations in elderly people. It mainly occurs when IVD degeneration has

caused narrowing of disc space, which approximates the vertebral bodies and

jams the posterior facets (Fig. 6.11). |

|

|

|

The last type of static subluxation, foraminal occlusion, may be a

consequence of one or more of those malpositions previously described (Fig.

6.13). |

|

|

Kinetic Intersegmental Subluxations

|

Segmental hypomobility, also called a "fixation subluxation" by many clinicians, may affect one or several motor units. |

|

|

|

Hypermobility, called loosening of the vertebral motor unit by Earl Rich

and Junghanns, may also be found at one or several levels. It is often found

as a compensatory mechanism accompanying hypomobility (fixation) at one or

more other levels in the kinematic chain. |

|

|

|

Aberrant motion exists when one or several vertebrae move in a way that is

not in coordination with neighboring segments during some movement of the spine. |

|

|

Sectional Subluxations

Sectional subluxations are another group to be considered. They comprise

disrelationships of a group of vertebrae.

|

Scoliosis and/or Alteration of Curves Secondary to Muscular Imbalance. Such disrelationships are quite common. |

|

|

|

Scoliosis and/or Alteration of Curves Secondary to Structural Asymmetries.

This is a frequently found scoliosis usually due to a short leg with pelvic

unleveling (Fig. 6.18). |

|

|

| Decompensation of Adaptational Curvatures. This is usually a relatively acute situation superimposed over a chronic deformity or distortion (Fig. 6.19). |

|

|

|

Abnormalities of Motion. These disorders can be found in spinal regions or at individual motor units (Fig. 6.20). |

|

|

Extraspinal Subluxations

Following are some case presentations depicting the various

classifications of subluxations described above. Also included are some facts

of historical significance, pertinent physical findings, diagnostic

conclusions, and a short description of the patient's response to chiropractic

management. The reader should keep in mind that these are not comprehensive

reports. They will, however, underscore some relevant points.

The final classification of subluxations consists of articulations in

which extraspinal structures articulate with the spine. The common

disrelationships occurring at these articulations (costotransverse or

costovertebral) are poorly shown radiographically, but the dysfunction

incidental to the disrelationship may well cause spinal distortions suggestive

of the subluxation. Marginal sclerosis of the articular surfaces is

presumptive evidence of the existence of a subluxation.

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Classification of Radiologic Manifestations

Case Illustrating Classifications

A-I (Flexion malposition) and C-3 (Decompensation of adaptational curvatures).

|

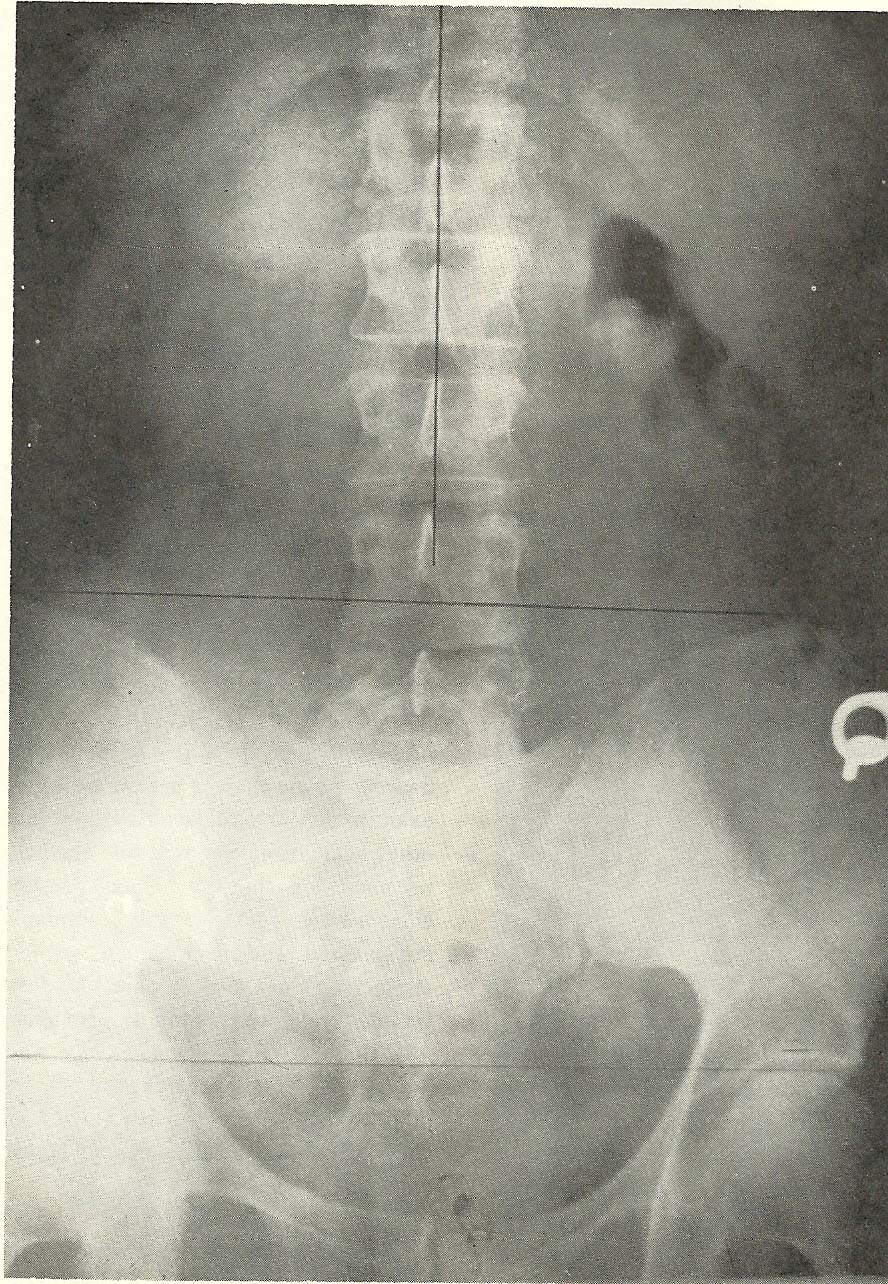

Note that there is a mild right-inferior pelvic tilt due to deficiency of

the right lower extremity in the film shown in Figure 6.21. Yet, there is no

distinct evidence of a lumbar scoliosis to the right as would normally be

expected. This interesting finding was observed as one of the roentgenographic

findings in the following case presentation. |

|

|

The lateral lumbar view (Fig. 6.22) shows a marked flexion subluxation of

L4 over L5 (A-1). In addition, we see loss of interosseous spacing at L5 and

S1. No other evidence of osseous or soft-tissue abnormality is noted on this

film. |

|

|

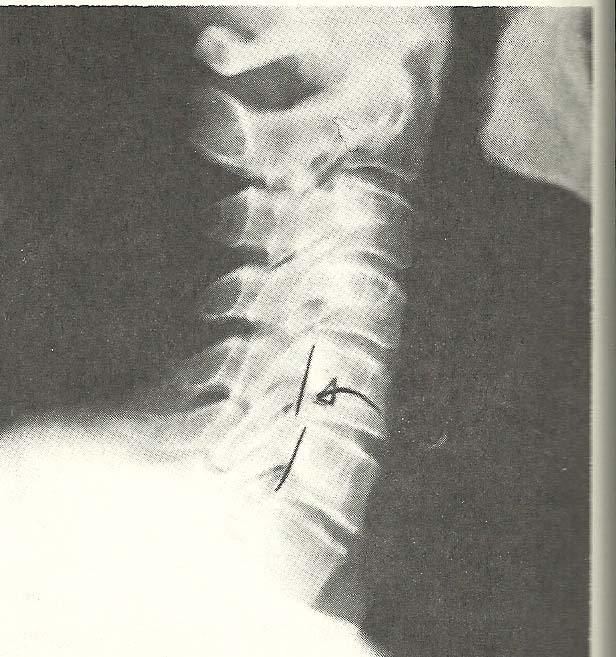

Case Illustrating Classifications

A-I (Flexion malposition) and B-2 (Scoliosis and/or alteration of curves secondary to structural asymmetries)

In this case, films of a 48-year-old female show a patient who has

sustained a torsion-flexion injury to the cervical spine when the automobile

she was driving was struck at the left front. She was taken in a conscious

state to the emergency room of the nearest hospital where she was given only a

brief examination and released without roentgen study or other evaluations.

She was told she lacked injuries and had no need for therapy. On presenting

herself to chiropractic service, she complained of marked stiffness of the

neck, blurred vision, vertigo, neck pain, and severe pain at both temples. She

reported no previous neck injury. |

|

|

In the forward-flexed position film (Fig. 6.24), hypermobility (B-2) of C4 is seen as a definite segmental subluxation of the hypermobile type. |

|

|

In the cervical extension position, restriction of the total range of mobility is seen (Fig. 6.25). |

|

|

The right posterior oblique film in flexion (Fig. 6.26) discloses unilateral hyperflexion of C4 over C5 and C5 over C6, with widening of the IVFs. |

|

|

The general alignment on the A-P

film is good (Fig. 6.27). |

|

|

Case Illustrating Classifications A-2, A-3, A-8, C-1, and C-2

One of the most common subluxations found in the lower back is that of

hyperextension of the vertebral motion unit. This usually accompanies, or is

caused by, a posterior shift of weight bearing and is frequently found

associated with an increased lumbosacral angle. It is characterized on film by

an approximation of the spinous processes, extension or imbrication of the

facet articulations, and posterior wedging of the interbody disc space. |

|

|

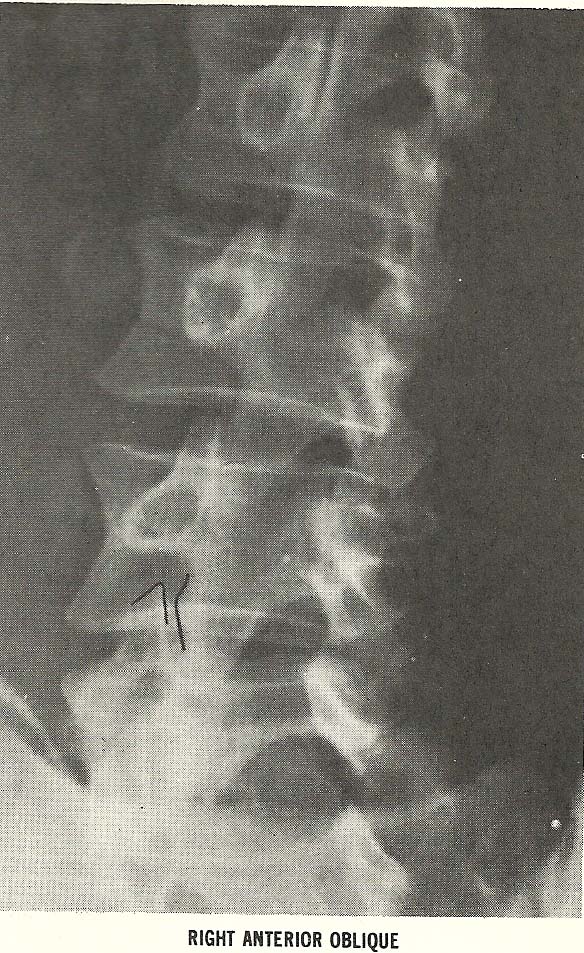

The oblique projection (Fig. 6.29) shows the downward displacement of the

L4 articular process relative to the opposing superior articular process of

L5. he contralateral oblique film demonstrates facet disrelationship on this

side that even more marked than that seen on the other side (Fig. 6.30). |

|

|

The right anterior

oblique film (Fig. 6.30) shows similar but less marked jamming of the facet

on the left. Reactive scoliosis is also obvious. |

|

|

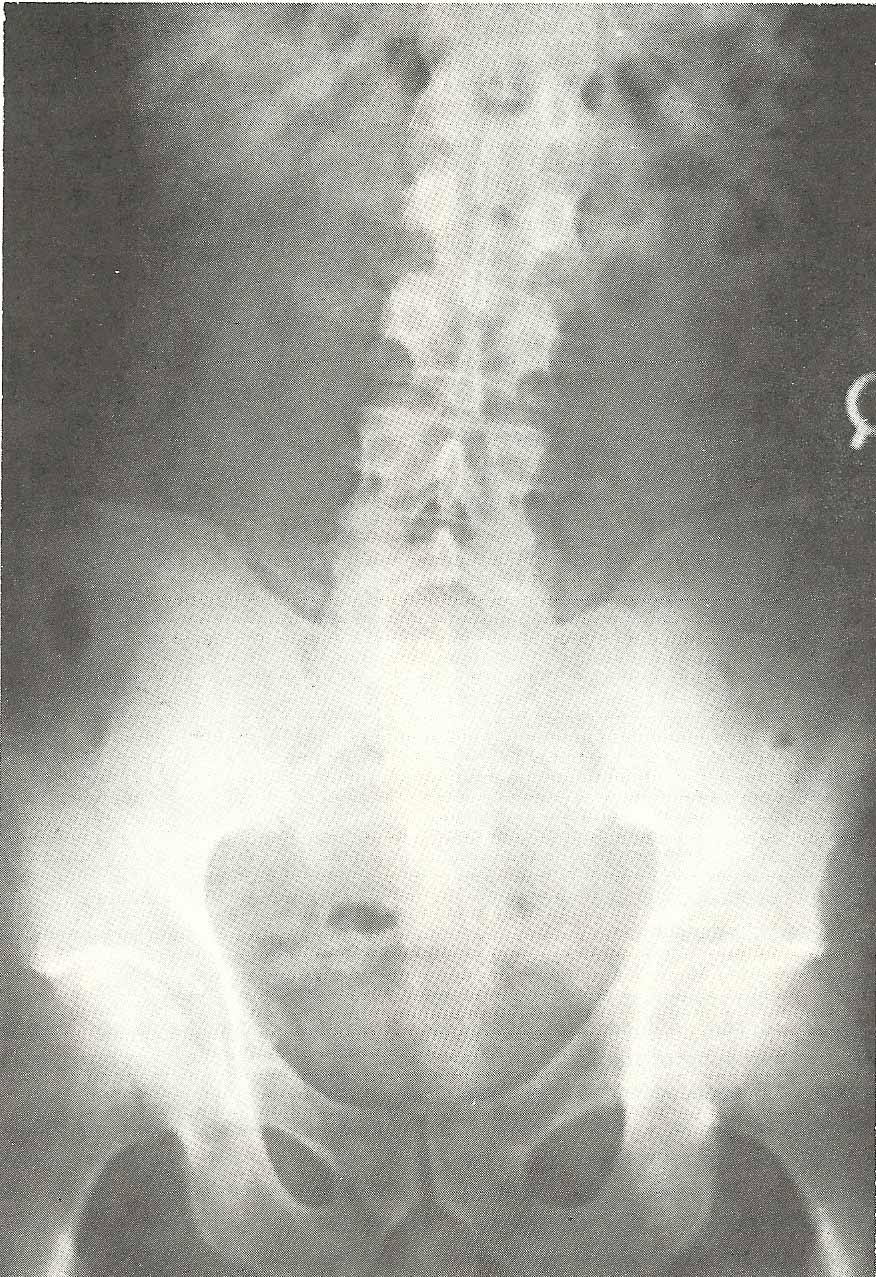

In the A-P projection (Fig. 6.31), we see a rather severe right

inclination of the vertebrae above L5, which produces a right rotoscoliosis

extending into the thoracic spine and including the vertebrae above those

visualized in this film. |

|

|

Extension subluxation (A-2) at L4-L5 (not shown).

Severe right lateroflexion subluxation at L4-L5 (A-3) in this case, at

least partially due to asymmetrical structural development.

Scoliosis cephalic to L4 from the L4-L5 facet asymmetry. Muscular

imbalance is also a factor in this scoliosis (C-1).

Narrow interosseous spacing at L5-S1 (A-8). Discopathy is the cause of the narrowed spacing at L5-S1, and there is resultant facet arthrosis.

As explained previously, the presenting complaint in this case was

low-back pain with sciatic neuralgia radiating down the left leg to the ankle.

The patient came to the doctor of chiropractic after having spent 2 weeks in

the hospital where hot packs, bed rest, and traction provided little relief.

He was taking Robaxin (methocarbanol), which gave little comfort, and said

that his MD had told him he was suffering from a "disintegrated disc."

Examination showed him to be in severe pain, with an obvious antalgic

posture. He was guarding his movements very cautiously. The pain was so severe

that a full physical examination could not be made. All low-back motions were

severely restricted, and sitting aggravated the pain. The patient was wearing

a back support provided by the orthopedic surgeon. Orthopedic tests brought

out the following signs:

Lasegue SLR: positive on right at 80°, left at 10°.

Goldthwait: positive on the left.

Well-leg raising: positive on the right.

Lewin supine: pain on left.

Gaenslen: positive on the left.

Kernig: positive on the left.

Leg rocking: positive on the left.

Ely's test: positive bilaterally.

The diagnosis was Grade 4 disc syndrome, and especially careful

chiropractic manipulation was started. A sitting disc adjustment afforded

marked relief almost immediately. He was then sent home to bed. The following

day the patient called and was in too much pain to come for treatment.

Two weeks from the date of first visit, he presented himself in worse pain

than at the time of the initial visit. He had been in the hospital for a week,

having been released the day before this visit. The orthopedic surgeon had

recommended disc surgery, and he was scheduled for a myelogram the next day.

A chiropractic adjustment again gave marked temporary relief. He was advised

to return home to bed and to have another treatment the next day. The DC's

reasoning concluded, since each adjustment helped temporarily, further

treatment might be worthwhile. However, the patient did not appear for

treatment the next day. A telephone call reported that he had returned to the

hospital. Disc surgery subsequently showed posterolateral herniation on the

left at L4.

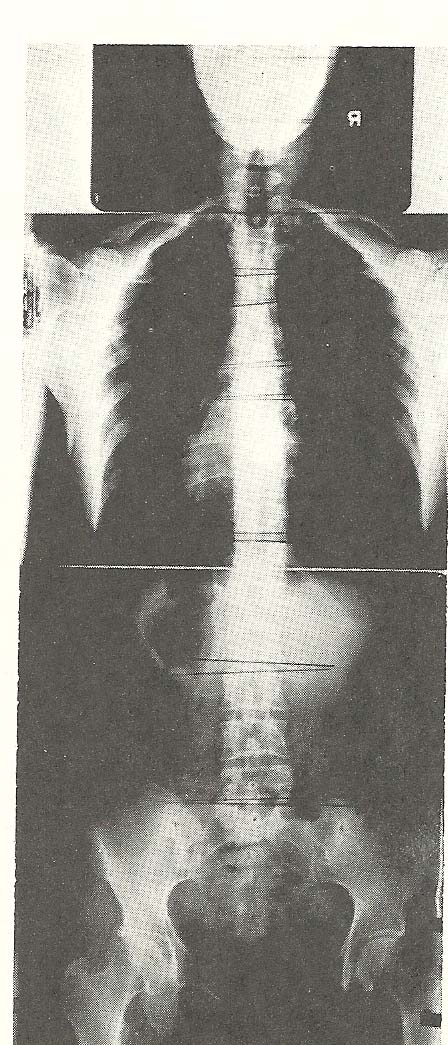

Case Illustrating Classifications A-2, A-2, A-6, A-9, and C-1

A 57-year-old female presented herself to a DC's office with the primary

complaint of low-back pain, which began approximately 6 days previously when

she was bent over to dust furniture. She had a history of low-back pain

approximately 10 years before this incident. The patient had a chronic

complaint of stiff neck, suboccipital headache, tinnitus, and frequent

paresthesias in both upper limbs, especially along the lateral aspect.

Physical examination showed:

(1) Blood pressure, 128/78.

(2) Pulse rate, 84.

(3) Auscultation of the heart and lungs revealed no abnormality,

(4) Abdominal palpation revealed no masses but some tenderness over the descending colon.

(5) Examination of the eyes, ears, nose and throat was unremarkable.

(6) On neurologic evaluation, the left patellar reflex was reduced. Other reflexes were normal. A mild hypesthesia was present along the lateral aspect of the right forearm and distally to the thumb. Passive elevation of the legs resulted in pain in the area of L4 and L5. Lasegue's SLR test was negative but restricted in range due to tight hamstring muscles.

(7) Because of a history of high serum cholesterol, blood was taken for this determination. Laboratory reports showed a cholesterol level of 257 mg%.

In the A-P film of the lumbar spine and pelvis (Fig. 6.32), a level pelvis

and sacrum is seen. |

|

|

The next film, a lateral lumbar view (Fig. 6.33), disclosed an extremely

marked hyperextension of the lumbar spine in general, with specific segmental

hyperextension occurring especially at L4 on L5, L3 on L4, and L2 on L3. |

|

|

The cervical films reveal several deviations from normal spinal alignment,

the most obvious of which is the retrolisthesis of the C5 segment (A-6). |

|

|

The cervical films reveal several deviations from normal spinal alignment,

the most obvious of which is the retrolisthesis of the C5 segment (A-6). |

|

|

Case Illustrating Classifications A-3

The radiograph shown in Figure 6.36 reveals an easily demonstrable left

lateral flexion subluxation of C3 upon C4 (A-3) and C4 on C5. |

|

|

Case Illustrating Classifications A-3, C-3, C-4, and D-1

The lateral lumbar view shown in Figure 6.37 is that of a 57-year-old

female. There is a loss of the normal lumbar lordosis. |

|

|

The anteroposterior full-spine films (Fig. 6.38) exhibit several

lateral flexion-type subluxations (C-3) and a rotational type at the level of

L5 (C-4). |

|

|

Case Illustrating Classifications A-3

A 53-year-old male presented himself to a chiropractic office with a

complaint of very acute lumbar pain with radiation into the right gluteal area

and posterior thigh. His pain started at his place of employment when he had

reached to the left in a slightly flexed position to pick up an object of less

than five pounds. He felt a sharp stabbing pain in the lower back and was

unable to straighten. He was taken to the plant infirmary where diathermy

treatments were applied, but these did not alleviate the symptoms. On

presenting himself for chiropractic care, he had great difficulty walking.

|

The A-P lumbopelvic film (Fig. 6.39) demonstrates an acute rotary and left

lateral subluxation of L4 (A-3), and there is a slight left posterior body

rotation of this segment relative to L5. |

|

|

The second film (Fig. 6.40), which was taken several days later, shows

complete reduction of the L4 subluxation. |

|

|

Case Illustrating Classifications A-4

This 53-year-old housewife presented herself with a complaint of neck

stiffness when awakening in the morning that was associated with stiffness and

discomfort in the right shoulder area. She said her problems brought on

headaches and a decreased ability to move her neck comfortably. She reported

episodes of this problem occurred frequently for a duration of more than 30

years. The length of her current problem was approximately 3 weeks.

In the past, she had obtained considerable relief from her symptoms

through chiropractic manipulative therapy, but her usual doctor of

chiropractic had retired. She said that medication prescribed by several

medical doctors had been of no help. The MDs who had examined her had told her

she had arthritis in her neck, and one told her "nine tenths of her body" was

so affected. She reported that she had been in three automobile accidents:

1940, 1943, and 1965. Exercise seemed to aggravate her symptoms. Her only

other presenting complaint was occasional low backache.

Her history revealed chronic eye strain and visual impairment. Chronic

postnasal drainage, supposedly associated with sinusitis, an appendectomy at

age 17, and partial hysterectomy at age 40 were revealed. She smokes 1-1/2

packs of cigarettes daily and drinks alcoholic beverages occasionally. No

liver or gallbladder symptoms were expressed.

Physical examination showed normal vital signs and an abdominal scar from

a hysterectomy but little else of significance. Orthopedic and neurologic

evaluations showed no abnormalities except a slight decrease in rotatory

cervical movements and some spasticity of the neck muscles. No orthopedic

tests were positive. The neurologic examination was normal except for slight

exaggeration of deep tendon reflexes in both arms and legs. A CBC showed

normal values. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and RA latex determinations

were negative. Urinalysis revealed no abnormal findings.

Routine x-ray examination of the cervical spine showed a relative

hypolordosis and a slight right convexity of the neck, with the head tilted

slightly to the left in normal posture. No significant degenerative or other

pathologic changes were noted. In fact, for her age and history, the lack of

obvious degenerative changes was remarkable.

The lateral cervical film (Fig. 6.41) shows evidence of rotational

disrelationships of the midcervical vertebrae (A-4). The axis and atlas show

relatively little rotation, but the articular processes of C2 are superimposed

over one another. To the contrary, C3 shows its articular processes to be

quite distinctly not superimposed. C4 is similarly rotated but less markedly

so. C5 and C6 show increasingly less rotation as evidenced by articular

superimposition. C7 is also neutral in rotation; its articular processes are

superimposed in the lateral view.

The A-P open-mouth film (Fig. 6.42) confirms the vertebral rotation. The

left head tilt causes rotation of the axis with its spinous process right of

central. This is the normal position for C2 with the head tilted left and no

significant facial rotation.

The lower cervical A-P film (Fig. 6.43) shows increasing deviations of

spinous processes to the right of central cephalad from C3 to C7 and the C3

vertebra shows the greatest deviation. The facets, as revealed by oblique

films (not shown), appear to be adequately aligned, and the neutral foramina

were patent.

To summarize the x-ray findings, we saw no demonstrable degenerative

disease. Rotational subluxations (A-4) are apparent in the midcervical region.

Treatment by chiropractic manipulative therapy brought prompt relief of

symptoms. She experienced a mild return of symptoms after 5 days, and returned

for further treatment a week following her initial visit. Weekly visits for 2

weeks more and another after a 2-week interval found her to be comfortable,

with no return of symptoms. She returned a month later with a mild recurrence

of symptoms, which were quickly alleviated. Two months have elapsed without

her return for further treatment. A telephone check showed her to be

asymptomatic.

Classification of Radiologic Manifestations

Case Illustrating Classifications A-4 and C-2

A 62-year-old Caucasian male presented himself to a chiropractic office

with the primary complaint of "gnawing" pain in the left hip. This condition

had existed for about 6 months, and the history further revealed a weight loss of

approximately 30 lbs since the previous October. At that time, he had

experienced upper abdominal pain and, after hospitalization, had been

diagnosed as having diabetes mellitus. He was placed on oral medication. The

weight loss had occurred in the interim from October to June. He had received

periodic "blood tests" that apparently were related to blood sugar

evaluations.

Physical examination revealed:

(1) normal blood pressure and pulse rate,

(2) slight systolic murmur over the mitral area,

(3) normal and equal deep tendon reflexes,

(4) abdominal palpation found hepatic and splenic enlargement,

(5) bilateral pitting edema of the lower extremities was elicited, and

(6) prostatic examination revealed mild hypertrophy.

The orthopedic evaluation revealed:

(1) bilateral leg lowering, positive left;

(2) Patrick's test, positive left;

(3) Lasegue's SLR test for the right leg caused pain on the left side;

(4) deep tenderness to pressure was found at the level of L3 bilaterally; and

(5) the lumbar range of motion was normal, although there was some pain in the left hip on left side bending.

The A-P film of the lumbar spine and pelvis (Fig. 6.44) demonstrates a

mild scoliosis due to structural asymmetry (a right lower-extremity deficiency

a definite right rotary subluxation

of L3 relative to L4 (A-4). Evaluation of the abdominal soft-tissues revealed

an inferior displacement of both the splenic and hepatic flexures of the

colon. The inferior border of the liver can be seen below the level of the

iliac crest, and the inferior border of the spleen is seen at the level of the

iliac crest. Although these films were taken in the upright position, the

probability of splenomegaly and hepatomegaly existed.

The oblique spot film of the left hip reveals a very mild degree of

degenerative joint disease (Fig. 6.45). The lateral lumbar film (Fig. 6.46)

shows mild proliferative change but with good maintenance of lumbar disc

spaces. There is a slight degree of lumbar hyperextension and osteoporosis.

The patient was instructed to return to his family physician for further

laboratory evaluation, only to be told that his weight loss was due to the

diabetes. During the interim, he received chiropractic care for his original

complaint of hip pain. Within 2 weeks, a marked improvement in the symptom

pattern was experienced, and he began to walk without favoring the left side.

During the course of treatment, trigger-point therapy was given and the

patient developed hematomas at the trigger-point sites. It was at this time

that the DC insisted on drawing blood, even at his expense, to do a CBC. The

report showed 386,000 WBCs. A diagnosis of probable myelocytic leukemia

(chronic) was made, and the patient was again referred to the family physician

--this time with full lab reports preceded by a phone call. The patient was

treated for the leukemia by chemotherapy, and the DC continued to treat the

hip disorder. The chiropractic diagnosis was one of L3 nerve root radiculitis,

with extension to the left hip.

Following 3 months of chiropractic therapy, the second A-P film was taken.

By use of a heel-lift, the pelvic tilt was somewhat corrected and the rotation

of L3 over L4 was reduced. The patient was released completely asymptomatic

relative to his primary complaint. He has not had a recurrence of this pain.

Classification of Radiologic Manifestations

Case Illustrating Classification A-5 (Spondylolisthesis)

Another classification of subluxation is spondylolisthesis. In this case,

we have a 46-year-old male who not only exhibits a classic spondylolisthesis

but also manifests many problems encountered in the average chiropractic

practice. These problems include a history of trauma involving litigation that

eventually resulted in a permanent disability award under Social Security,

which qualified him for Medicare coverage.

The patient stated that, while walking across a temporary ramp at a

building under construction, he caught his heel on a nail and fell with a

twisting motion. This resulted in immediate pain in the lower back and left

buttock area. His lower back continued to hurt and steadily became worse, with

the pain extending the full length of the left leg. He said he had never had

symptoms of back trouble before this accident.

The patient was taken to a chiropractic office and was ambulatory with

assistance. He had difficulty supporting his weight and undressing for the

examination. He was unable to perform any mobilization test for the lower

back. All passive tests for the low back were positive. There was severe

trigger-point tenderness bilaterally from the lumbosacral joint, symptoms of

left sciatic neuralgia, rigidity in the lower lumbar muscles, and the deep

reflexes of the lower extremities were sluggish.

The lateral radiograph (Fig. 6.47) reveals a distinct anterior

displacement of L5 in relation to another peculiarity of this case, a

transitional lumbosacral segment. This transitional segment is immovable

because of synostosis with the sacrum on the left. Therefore, the segment

above (L5) becomes the lowest freely movable vertebra in the spine (Fig.

6.48).

This anterolisthesis subluxation (A-5) can be graded by several methods,

one of which is a percentage evaluation of anterior body displacement. We

value this as a 20% spondylolisthesis (Grade 1).

In typical cases, the predisposing factor toward spondylolisthesis is a

defect where there is no osseous connection at the pars interarticulari. It

may be bilateral or unilateral. A pars defect, a spondylolysis, is best

visualized only on carefully positioned oblique views. Here, the spondylolysis

is well demonstrated in both right and left views (Figs. 6.49 and 6.50).

Chiropractic treatment was started in an attempt to improve biomechanical

function of the lower spine. This was accomplished to a great extent within 3

months. However, the spondylolisthesis and spondylolysis are irreversible and

will result in continued instability. Periodic treatments as clinically

indicated may be required, depending on the patient's activities.

Classification of Radiologic Manifestations

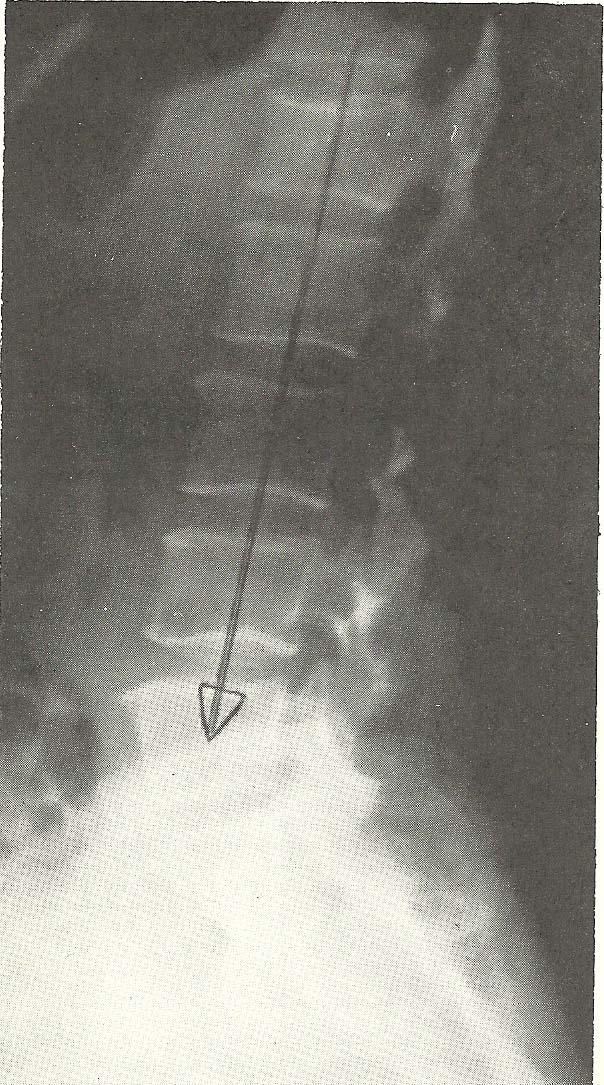

Case Illustrating Classifications A-5, A-6, A-8 and A-9

This case again shows coexistence of several classifications of

subluxations and serious alteration of mechanical functioning of the neck.

This 65-year-old female gave an extensive history of many illnesses and

consulting many doctors of various specialties over several years. Her history

revealed many complaints, both old and recent. She had experienced radical

mastectomy of the left breast 21 years before her first consultation at a

chiropractic clinic. Her chief complaint on the first visit was continuous

neck pain of 4--5 weeks duration. She also complained of chronic occipital

headaches, eye pain, pain radiating into the left shoulder, paresthesias of

the neck and left arm, and pain sometimes extending to the left elbow.

Questioning revealed a history of "arthritis" affecting her neck and low

back, gastritis and intestinal disturbances with discomfort after meals,

nervousness, and pain on micturition on occasion for which she consults a

urologist and periodically has urethral dilatation. These conditions were of

several years duration and for which she takes prescribed medication. She had

a L5 laminectomy 5 years ago, a hysterectomy at age 49, a cholecystectomy at

age 30, surgery for an ectopic pregnancy when in her 20s, and an appendectomy

while in her 20s. She suffered bronchopneumonia on one occasion in youth. A

year before her visit to the chiropractic clinic, she had experienced viral

pneumonia.

Physical examination showed her to be obese at 160 pounds for her height

of 5 feet 2 inches. Her vital signs were essentially normal, with blood

pressure of 130/78 left brachial; 136/80 right brachial. The significant

abnormal findings were:

(1) Obvious postural distortion, especially in the neck, which carried toward the anterior. There was pain on the extremes of neck motion, with slight diminution in range of motion.

(2) The cervical compression test was positive bilaterally, worse on the left.

(3) Moderate lymphedema of the left arm.

(4) Absence of the left breast.

(5) Several scars over the abdomen and lower back consistent with the surgical history.

(6) Tenderness over the stomach and flexures of the colon. Other abnormal findings were apparent.

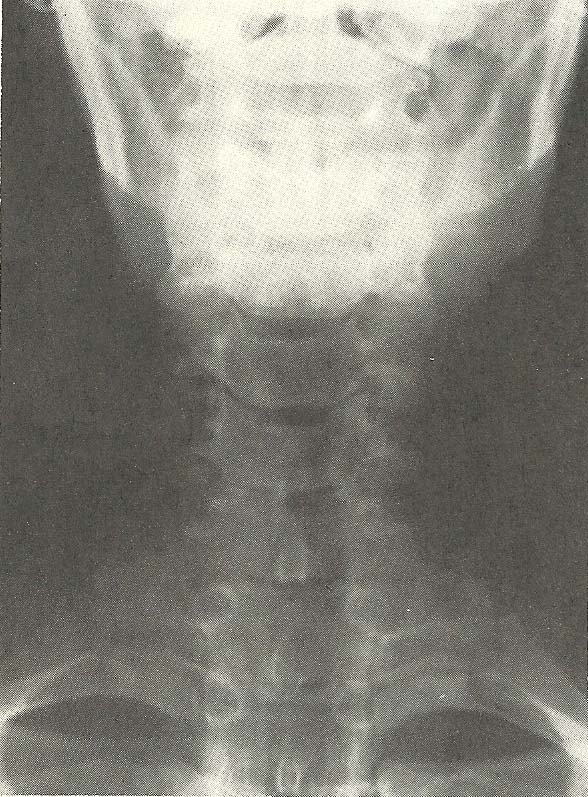

Cervical spine films revealed several abnormalities. Significant

generalized osteoporosis was evident by the relative radiolucency of osseous

structures and lack of trabeculations within the visualized bone. Spondylotic

hypertrophy and spurring of vertebral body margins were not severe but present

throughout the neck. Sclerosis of the articular facet surfaces is evidence of

degenerative joint disease. The disc narrowing at C4-C5, C5-C6, and C6-C7 is

noted. Several subluxations are apparent on the neutral lateral film alone

(Fig. 6.51). C2 shows slight anterior displacement upon C3, with C4 (A-5)

showing more anterior disrelationship relative to C5. C5 shows posterior

displacement upon C6 (A-6). The anterior carriage of the head alters the

cervical lordosis.

The lateral film taken during flexion of the neck fails to reveal

significant overall reduction in flexion, but a little flexion is seen at the

atlanto-occipital motion unit (Fig. 6.52). The anterior disrelationship of C2

upon C3 and C4 on C5 is not significantly altered during flexion, but the

posterior disrelationship of C5 upon C6 is improved.

General extension of the neck is adequate with all motion units extending

to the greatest degree allowed by structure (Fig. 6.53). In hyperextension,

there is no apparent alteration of the anterolistheses at C2-C3 and C4-C5, but

the retrolisthesis at C5-C6 is exaggerated as compared to the position in the

neutral lateral film.

The open-mouth A-P film is essentially unremarkable, but the A-P of the

lower cervical region (Fig. 6.54) shows considerable proliferative change of

the posterior facets at C4-C5 on the right and less hypertrophy at other

levels.

The oblique films (Fig. 6.55) show encroachment of the neural foramina at

C3-C4, C4-C5, C5-C6, and C6-C7 on the left with similar changes on the right

due to the uncovertebral arthrosis and uncinate hypertrophy (A-9).

X-ray examinations of the thoracic spine and the low back were also

conducted. They showed severe osteoporosis and moderately severe spinal

degenerative disease. The L5 laminectomy was demonstrable. These films and the

chest studies (which were essentially normal except for the left mastectomy)

are not shown here.

In summary of the cervical spine x-ray findings, we note generalized

osteoporosis and spinal degenerative disease of moderate severity. The

subluxations observed were:

(1) Anterolisthesis at C2-C3 and C4-C5 (A-5). Note that these are not the usual spondylolistheses seen in the lumbosacral area that show defects in the pars interarticulari. These anterolistheses are allowed by the disc and articular degenerative changes. They do not change significantly in flexion or extension of the neck.

(2) Retrolisthesis at C5-C6 (A-6), which is somewhat unstable and shows moderate hypermobility and abnormal motion on neck flexion and extension.

(3) Foraminal alteration or encroachment (A-9) at nearly every level in the neck bilaterally due to degenerative change and malposition of the vertebrae.

(4) Decreased interosseous spacing (A-8) from disc degeneration.

(5) Aberrant motion (B-3) with various motion abnormalities seen on stress study.

Blood chemistries and serology did not reveal significant deviations from

normal. Hematology showed a slightly low hemoglobin (11.5 grams), but

otherwise was essentially normal. Urinalysis did not show significant

abnormality.

This patient was treated with conservative chiropractic care and

encouraged to continue with the medical specialists who were attending her

when she consulted the chiropractic clinic. She showed slow improvement in the

neck and shoulder pain, and the headaches diminished in severity and

frequency after only a few treatments. She continued under chiropractic care

for almost 2 years, receiving frequent treatments for approximately the first

2 months of care, at which time she was advised that her problems would

probably show little further improvement. She felt that she received benefit

from the treatments and continued to present herself once or twice a month

after that. Subsequent x-ray films of the spine were made after 14 months.

They showed essentially no change. At her last visit, somewhat more than 2

years after the initial chiropractic examination, she was only slightly

improved, having many complaints and experiencing only temporary relief

following treatment.

Classification of Radiologic Manifestations

Case Illustrating Classification A-7

We see here an unusual complex of anomalies accompanied by a

laterolisthesis type of subluxation (A-7) and a gross postural alteration.

This 55-year old pharmacist complained of severe, nearly constant, pain

affecting the lower back. He had suffered from varying degrees of low-back

pain for most of his life. The problem became progressively worse with

advancing age.

The gross trapezoidal shape of the lower two lumbar segments shown in

Figure 6.56 shows the result of anomalous segmentation. A hemivertebra may

take varying forms. In this case, there are two half vertebrae forming the

right portion of the upper trapezoidal segment and two half vertebrae forming

the left portion of the lower segment. These are completely fused, resulting

in a grossly unlevel superior surface of the lowest mobile vertebra. This

causes a severe disrelationship combining rotational and lateral displacement

(a laterolisthesis subluxation).

These gross abnormalities are expected to cause eventual degeneration

despite proper maintenance care. In review, we can arrive at a diagnosis of

double hemivertebra of the lower lumbar segments with a laterolisthetic

subluxation (A-7).

Classification of Radiologic Manifestations

Case Illustrating Classifications A-1, A-3, A-4, A-7, and A-8

A 65-year-old male laborer presented himself for chiropractic care. He

reported a primary complaint of acute low-back pain centering between L2 and

S1 and was unable to work because of the pain. His history revealed very

little low-back pain before this incident despite his heavy work. The pain

was precipitated by a fall on ice.

Physical examination was relatively unrevealing except for the following

orthopedic tests:

(1) Hyperextension of the lumbar spine produced increased pain.

(2) Lasegue's SLR and Goldthwait's tests were positive bilaterally.

(3) The lumbar ranges of motions were markedly restricted in all directions.

(4) The normal lumbar lordosis was flattened.

X-ray films of the lumbar spine were taken that revealed left lateral

flexion of L5, which was best noted in the AP film (Fig. 6.57) by the

approximation of the left transverse process of L5 to the left sacral ala

(A-3). Severe rotational disrelationship of L4 to L5 (A-4) with slight right

lateral flexion of L4 on L5 has produced a left laterolisthesis (A-7) of L4.

L3 showed less rotation than L4, and L2 was in a position of reverse rotation

(A-4) to the right so that an unusual left lower lumbar rotoscoliosis was

formed with a slight right rotoscoliosis in the thoracolumbar area.

The lateral film showed decreased interosseous spacing (A-8) throughout

the lumbar spine, with the least amount of disc narrowing noted at L4-L5. Loss

of normal lumbar lordosis is also exhibited (Fig. 6.58). These changes have

produced multiple flexion disrelationships (A-1), particularly in the upper

lumbar area. Both A-P and lateral films showed marginal proliferative changes

that were evidence of chronic disc degeneration. Moderate generalized

osteoporosis is also present. By correlating these findings, a working

diagnosis was made of lumbosacral strain with myofascitis superimposed on

moderate spinal degenerative disease.

The subluxations noted are of several types, including:

(1) laterolisthesis of L4 on L5 (A-7);

(2) decreased spacing throughout (A-8);

(3) flexion malposition of the upper lumbar vertebra (A 1);

(4) left lateroflexion of L5 on the sacrum (A-3); and

(5) reverse rotation of L3 on L4 and of L2 on L3 (A-4).

Conservative chiropractic therapy was started. The patient was seen six

times over a period of 4 weeks, with complete relief of symptoms. He could

return to work after 10 days of treatment and was subsequently discharged with

the advice that he should return for care as symptoms warranted. With the

degree of degenerative changes present, he will likely have recurrent low-back

problems.

Classification of Radiologic Manifestations

Case Illustrating Classification A-8

A 58-year-old housewife presented with a primary complaint of heavy aching

pain between the shoulder blades, with a tendency toward sharp cutting pains

to the front of the chest on awkward movement or coughing. She further

complained of difficulty in breathing at times. These symptoms had occurred

periodically over the past 5 years and were becoming more frequent and severe.

Physical examination did not show significant alteration of normal

cardiovascular or pulmonary function. A detailed spinal examination revealed

rigidity and tenderness of the thoracic paraspinal muscles, especially on the

right in the lower thoracic area. Muscle testing against resistance

demonstrated weakness of both divisions of the pectoralis muscles bilaterally.

The lateral film shows marked narrowing of the intervertebral disc spaces

throughout the thoracic spine (A-8). Note reactive hypertrophic and sclerotic

changes along the vertebral body margins, indicating a chronic condition (Fig.

6.59). This film definitely exhibits decreased interosseous spacing at

multiple intervertebral levels. These subluxations, associated with

thoracocostal myofascitis, and the other findings led to a working diagnosis

of moderately severe thoracic degenerative disease.

Conservative chiropractic management was begun and, after six treatments

over a period of 2 weeks, considerable symptomatic relief was obtained. After

that, weekly adjustments were advised that resulted in continued improvement.

She was relatively symptom free after 4 more weeks. The patient's diagnosis

suggests that she will have periodic recurrence of symptoms requiring further

treatment.

Classification of Radiologic Manifestations

Case Illustrating Classifications A-1, A-3, A-4, A-8, and A-9

The x-ray views presented next are those of a 69-year-old female (Figs.

6.60--6.62). There is foraminal narrowing at four levels on the right and two

on the left due to proliferative changes (A-9). Flexion subluxation exists at

C4 (A-1), and marked interspace narrowing is found at C5, C6, and C7 (A-8). A

loss of normal cervical lordosis is evident. Rotary subluxation is present at

C2 and C3 (A-4). Also note the generalized osteoporosis.

This lady complained of objective vertigo, tinnitus, and suboccipital pain

and pressure. She had consulted her family physician 2 weeks previously, at

which time she received an ECG, chest x-ray, and several blood tests. She was

informed that nothing serious was wrong and her symptoms were related to a

"weak chest."

Chiropractic examination revealed the following pertinent information:

(1) blood pressure, 190/110;

(2) pulse, 108;

(3) height, 5 feet 5 inches;

(4) weight, 123 lbs;

(5) cicatrix formation of the left tympanic membrane due to an old rupture;

(6) postnasal drip with hyperemia of the posterior pharynx;

(7) on auscultation, slight accentuation of the aortic sound; and

(8) the ranges of cervical motions showed restricted flexion and extension as well as in right lateral flexion; and

(9) a cervical compression test was positive bilaterally.

A working diagnosis of hypertension, possibly of neurogenic origin, was

made. The patient was placed on a program of conservative chiropractic care,

and after a month her blood pressure had stabilized in a range between 140/80

and 150/80. At the same time, her vertigo, tinnitus, and suboccipital pain

were eliminated, and the ranges of cervical motions were increased. She was

placed on supportive treatment at this time.

Classification of Radiologic Manifestations

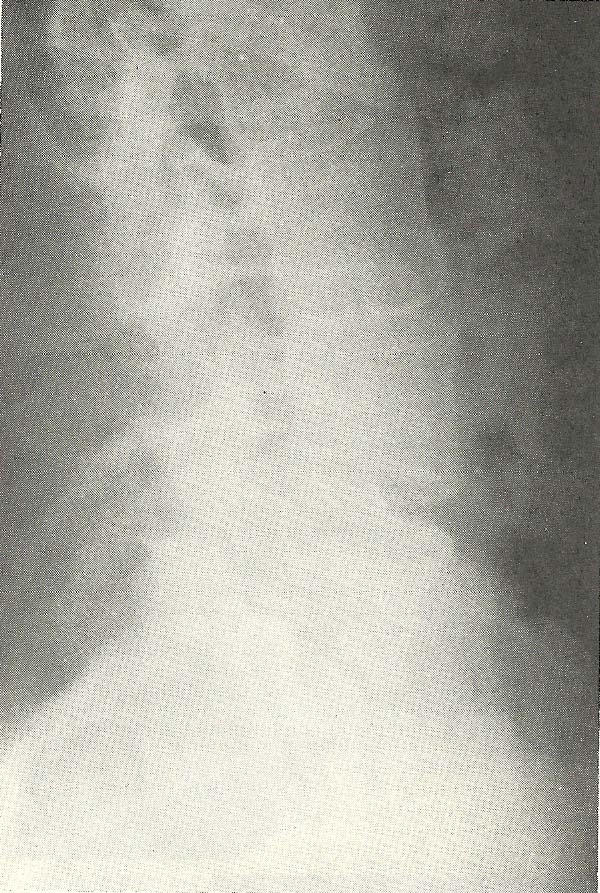

Case Illustrating Classifications B-1, C-2, C-4, A-8, and A-9

The films of this case (Figs. 6.61--6.67) show alteration of the cervical

lordosis in the neutral lateral film and lessened ability to flex the neck,

coupled with slight hypermobility during neck extension (C-4).

As the cervical curve is naturally convex toward the anterior, alteration

of this pattern usually means pathology or significant injury to the skeletal

and/or supportive structures. Note in the neutral lateral film that there is

flexion of the C3 and C4 motion units.

With neck flexion, near total fixation or hypomobility from C3 through C6

motion units (B-1) is demonstrated. The atlantoaxial and atlanto-occipital

motion units show considerably diminished ability to flex (B-1).

Extension of the neck is accomplished, even to the point of hypermobility.

All motion units extend as far as structure allows so that the posterior

arches and spinouses approximate. By comparing the three lateral films (Figs.

6.63--6.65), we have an excellent example of abnormal mobility of a spinal

section or region (C-5). Intervertebral hypomobility is present at several

levels.

This case also exhibits manifestations of other radiologically evident

subluxations. The decreased disc height at C4-C5, C5-C6, and C6-C7, due to the

evident discopathy and spondylosis, is classified as decreased interosseous

spacing (A-8). The rather marked intrusion and compromise of the neural

foramina at C4-C5, C5-C6, and C6-C7, seen on the left anterior oblique film

(Fig. 6.66), and similar alteration of the foramina at the same levels

are shown on the right anterior oblique film (Fig. 6.67), also meet the

criteria of subluxation under the classification of foraminal encroachment

(A-9).

The patient is a strong 66-year-old male who has continued to work as

manager of a solid-waste disposal plant though he had passed the age of

retirement. He was suffering from pain in the neck, which radiated to the

right shoulder. The duration of the complaint, at the time the x-ray films

were made, was 3 weeks. He had this complaint on several previous occasions

and each time had experienced an excellent remission of symptoms following

chiropractic treatment. He had not had similar pain for about 3 years prior to

the time he presented himself for chiropractic care for the current episode.

Views of the right shoulder, one of which is shown in Figure 6.68, were

essentially normal. Physical examination was largely unrevealing, except that

orthopedic testing showed grossly restricted ability to laterally bend the

neck to either side, and foraminal compression tests were positive

bilaterally.

The moderately severe degenerative disease the x-ray examination reveals

in this man's neck are chronic. The relatively short duration of the present

symptom complex suggests that his current pain is more related to neuralgia

from functional disturbance in his neck than to a chronic neuropathy. The

foraminal encroachment of sufficient magnitude and severity to suggest neural

canal stenosis.

Chiropractic adjustment and reflex techniques brought marked relief in

three treatments over a 1-week span. Two treatments the following week were

able to bring a near total remission of the pain. He continued with weekly

treatments for 2 more weeks, stating that he felt markedly better. Following

the 4th week of care, he was discharged from active treatment and advised to

return periodically as symptoms dictated. He has continued with monthly

visits, at his request, since he feels much better under such a regimen.

Classification of Radiologic Manifestations

Case Illustrating Classifications C-1, A-1, A-3, and A-8

Frequently several subluxations of different classifications are

demonstrable in spinal films of a specific patient. This case illustrates such

a situation. Alteration in the lumbar lordosis and an antalgic lateral list of

the lumbar vertebrae (both of which represent subluxations classified as C-1:

alteration of the spinal curve secondary to muscular imbalance) are noted.

Concurrently, flexion subluxation (A-1) is noted at L4 L5 and at L5-S1,

narrowing of the disc interspaces (A-8) being evident at both these levels.

Right lateral flexion of L4 upon L5 (A-3) can be suspected from the A-P

film (Fig. 6.69). Wedging of the disc interspace at L4-L5, narrow on the

right, is seen; and although the L5-S1 interspace is only poorly depicted on

the standard A-P film, it may be narrow on the left.

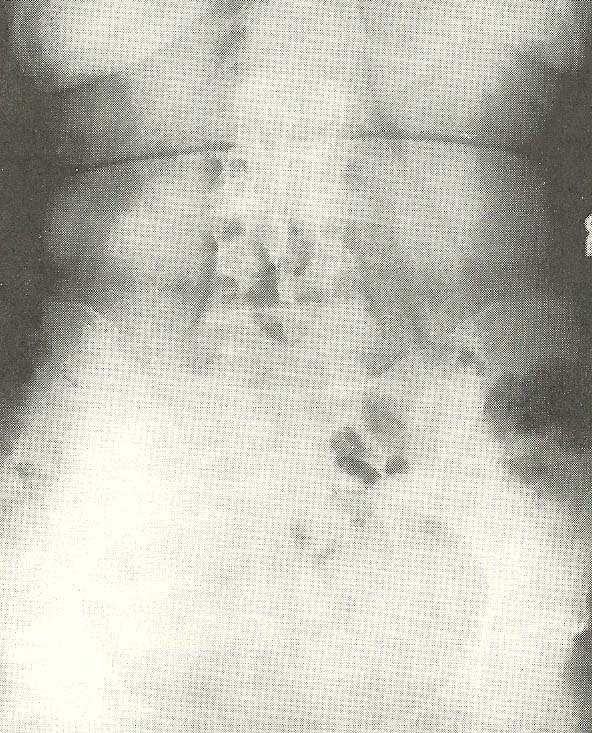

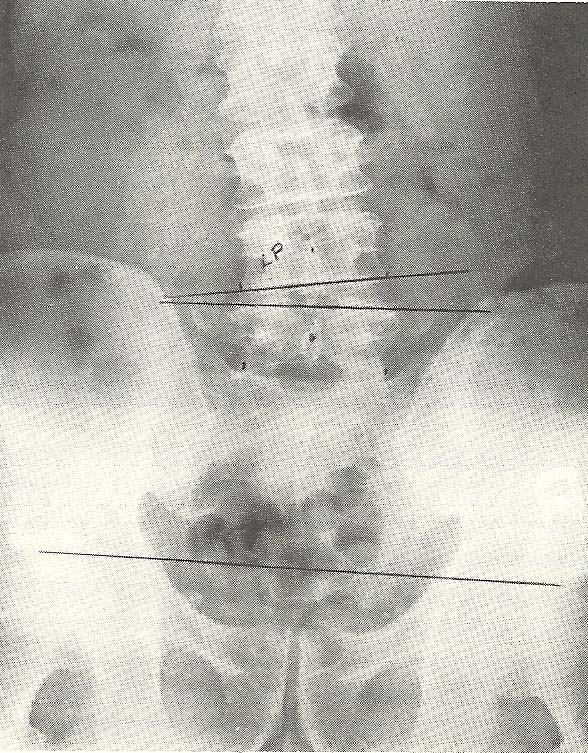

By use of the spot A-P film (Fig. 6.70), making the central ray

approximately parallel to the sacral base, the L5-S1 disc is better seen and

its wedging toward the left is more apparent. This projection gives an

excellent view of the lumbosacral junction and the extent of degenerative

spondylosis. The standard A-P and the lateral film (Fig. 6.71) showed the

obvious marginal spurring of the vertebral bodies at the two lowest motion

units.

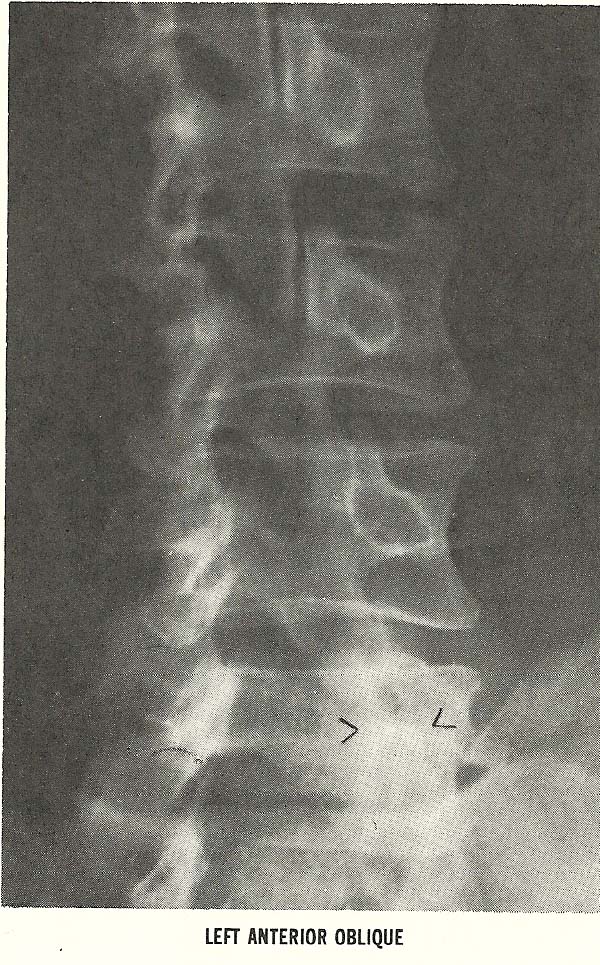

Oblique projections gave an enhanced ability to visualize facet

articulations and are especially valuable in determining subluxations. The

left anterior oblique view is taken with the patient prone, then turned 45°

with the left side near the film (Fig. 6.72). This case shows the

approximation of L4 and L5 vertebral bodies and the extent of the spondylotic

changes along the vertebral body margins from L3-L4 caudally and depicts the

facet articulations. Note that the right L4-L5 facets show imbrication or

downward displacement of the L4 articular process relative to those of L5, the

discrepancy at the superior of the articulation being evident. Note also the

sclerosis of articular surfaces at this facet, which is evidence of

degenerative arthrotic changes. At L5-S1, there is also slight imbrication and

definite arthrosis.

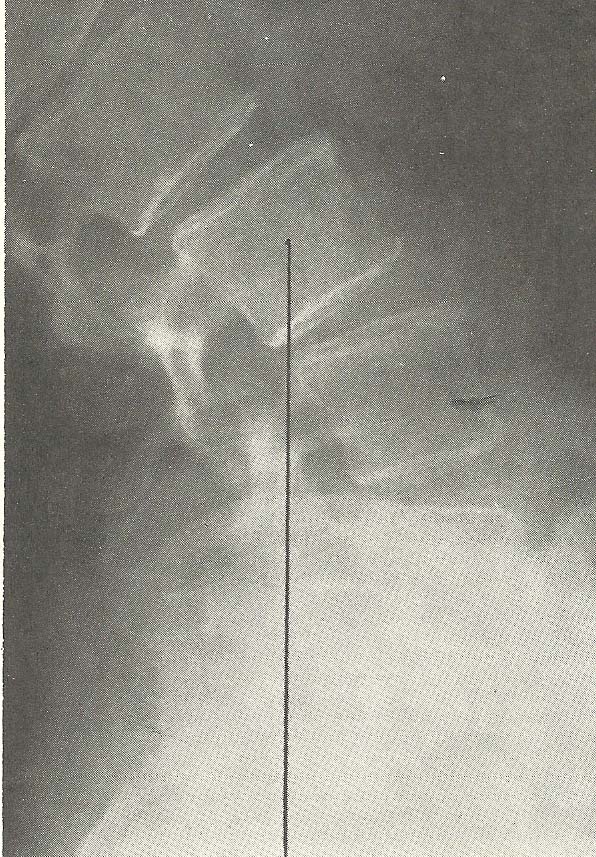

The opposite oblique film, the RAO, shows the left articular structure

(Fig. 6.73). In this film, the L4-L5 articular processes do not show

imbrication, but arthrosis is obvious. The presence of imbrication on the

right facet is seen on the other film. The lack of it on the left of this

motion unit verifies that there is right lateral flexion of L4 relative to L5.

At L5-S1, the obliquity of the facet articulation makes the facet joints less

easy to visualize. The marginal sclerosis of the articular processes shows a

degenerative reaction to chronic stress. Observe that the superior articular

process of S1 approximates the inferior surface of L5's pedicle on the left,

which is evidence of imbrication and verifies left lateral flexion of the

L5-S1 motion unit. Again, the spondylotic changes of the vertebral body

margins are easily seen.

To summarize the roentgenographic findings, there are:

(1) Degenerative spondylosis, facet arthrosis, and disc narrowing.

(2) Alteration of the lumbar lordosis and listing or deviation of the lumbar vertebrae to the right, presumably due to asymmetrical muscular spasticity, and antalgic mechanisms.

Several classifications of subluxation are evident:

(1) Decreased interosseous spacing (A-8).

(2) Flexion subluxation at L4-L5 and L5-S1 (A-1), which is incidental to the flattened lordosis and disc narrowing.

(3) Lateral flexion subluxations at L4-L5 and L5-S1, opposite inclination (A-3).

(4) Alteration of spinal curves due to muscular imbalance is also considered a subluxation of the spinal region or section (C-1).

This patient has a chronic low-back problem and has had recurrent episodes

of low-back pain for approximately 10 years. These usually result from

prolonged or strenuous work. He is a retired lithographer whose work often

required heavy lifting. His most recent complaints were of 2 weeks duration,

with pain predominantly perceived at the lumbosacral junction No radiation of

pain to buttocks or legs were reported. This disorder had been present since

the patient shoveled snow, and it remained relatively constant and of moderate

severity. Some relief was obtained while recumbent. He was in obvious discom-

fort both while sitting and standing. He had consulted with his family MD but

had not received satisfactory relief from the medication prescribed.

The physical examination findings were essentially within normal limits

for a 66-year-old male. Orthopedic tests revealed some restrictions in all

ranges of motion in the low back with no other significant positive findings.

There were no abnormal neurologic responses. Imbalance of the low-back

musculature was noted, especially weakness of the left psoas and quadratus

lumborum muscles and bilateral spasticity of the erector spinae muscles.

Conservative chiropractic treatment provided some relief after the first

treatment, and the patient was relatively asymptomatic after 10 days and three

treatments. Because of the history of recurrent problems and of moderately

severe spinal degenerative disease, the patient was advised that periodic

treatment would be helpful in discouraging recurrence of his pain, and that

exercises to strengthen the lower back and abdominal muscles, along with use

of a lumbosacral support during strenuous activity, might be of value.

Classification of Radiologic Manifestations

Case Illustrating Classification C-1 and A-1

Acute subluxations are frequently caused by or at least associated with

muscle spasm and imbalance following either major or minor trauma. The

following case is an illustration of this and demonstrates a rapid return to

normal after treatment alleviated the abnormal spasticity.

This patient first presented himself for chiropractic care after a minor

auto accident, following which he experienced transient neck pain. The initial

lateral cervical radiograph shows a normal to slight hyperlordotic cervical

curve, with hyperextension subluxations at C3 and C4, and little else (Fig.

6.74).

The second lateral cervical film --also a neutral lateral, at least as

nearly as his pain would allow, was taken 7 months after the first, the

exposure was made 3 days after a severe auto accident when his neck was

extremely painful (Fig. 6.75). Note the reversal of the lordosis (C-1) and the

definite flexion disrelationship at C3-C4 (A-1).

The third neutral lateral was taken 5 weeks after the second. In it, a

return to normal vertebral alignment is seen (Fig. 6.76). Chiropractic

manipulative therapy gave thorough relief within a few days after the first

accident.

The second, more serious accident, obviously caused more problems --both

to the patient and to the management of his case. After the second accident,

physical examination showed marked restriction of neck mobility and severe

pain even when the neck was not moved. Relief occurred following especially

careful chiropractic manipulation, and the patient was relatively asymptomatic

by the 4th week following the accident. Improvement had been steady from the

first treatment until that time. The diagnosis in this case was acute cervical

sprain.

Classification of Radiologic Manifestations

Case Illustrating Classifications C-2 and A-3

A 50-year-old male entered chiropractic care with a complaint of sharp

pain centering around the right hip and radiating down to the middle of the

anterior aspect of the right thigh. His history revealed malaria and scarlet

fever.

During the examination, it was determined that lateral flexion of the

lumbar spine to the left was markedly restricted. Flexion and extension were

adequate. Mild hypertension was encountered, though other vital signs were

unremarkable. Palpation of the abdomen revealed an enlarged liver

(approximately 3 cm). Since this man had recently received a CBC and liver

profile, these tests were not repeated. Orthopedic testing of the lower spine

was negative. However, trigger points were found in the gluteus medius and the

tensor fascia lata on the right.

Roentgen evaluation of the right hip disclosed no pathology. During

upright evaluation of the lumbar spine and pelvis, however, a scoliosis of the

lumbar spine was noted. The convexity was directed to the left side. This

scoliosis was secondary to a structural asymmetry in the form of a 13-mm

deficiency of the left lower extremity (C-2). Compensatory right lateroflexion

subluxations were evident at L3 and L2 (A-3). The illusion of right posterior

rotation of the lumbar spine is due to left anterior pelvic rotation over the

femurs (Fig. 6.77).

The lateral lumbar film shows mild degenerative change at the L3 disc,

with other lumbar discs of normal vertical height. A small amount of calcific

deposition is present in the abdominal aorta (Fig. 6.78).

A diagnosis of a short-leg syndrome, with nerve irritation at the L2-L3

and L3-L4 levels, was made. The extension neuralgia to the thigh was

responsible for the patient's symptoms. With conservative chiropractic

management, which included lift therapy, the patient's symptoms were

completely relieved within a month. During this time, he received nine

treatments, which resulted in partial correction of the leg deficiency. He has

not had a recurrence of symptoms at this time.

Classification of Radiologic Manifestations

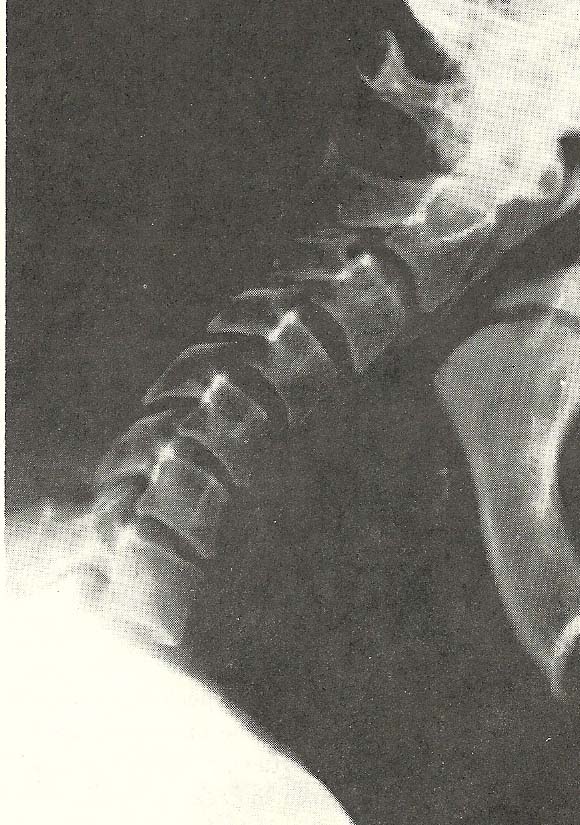

Case Illustrating Classifications C-4 and B-1

Another instance of altered vertebral mobility is shown in this case. The

altered cervical curve (hyperlordosis) shown in the neutral lateral film is

obviously associated with minor anomalies of the vertebral arches and

articular processes at C2--C4 (Fig. 6.79). There is also obvious arthrosis of

the facets throughout the neck, especially at C2-C3, and disc wedging to the

posterior is evident at C3-C4.

Flexion of the neck (Fig. 6.80) is grossly abnormal, the motion occurring

mainly as anterior bending of the neck as a unit --the lordosis remaining

essentially unchanged compared to the neutral film (Fig. 6.79). This

illustrates extreme hypomobility of nearly every cervical motion unit (B-1)

and abnormal motion of the cervical spine as a whole (C-4).

Extension of the neck is fairly well accomplished overall. At individual

motion units, however, one can see signs of restriction or hypomobility,

especially at C6 and C7 (B-1) where a comparison with the neutral film shows

little intervertebral extension (Fig. 6.81).

This 70-year-old male had a long history of neck pain and stiffness

associated with frequent headaches and bilateral shoulder pain. Orthopedic

tests showed diminished ranges of motion in all directions in the neck.

Cervical compression tests were negative.

Manipulation and adjustments of the neck were painful to him unless very

gentle techniques were used. Muscle stretching and postural correction gave

him some measure of increased comfort. After several weeks of various

manipulative approaches and changing intervals between treatment, it was found

that a treatment every 2 weeks helped him to experience less neck discomfort

and headache. He has remained on this schedule for several years.