The Efficacy of Manual Therapy and Exercise

for Treating Non-specific Neck Pain:

A Systematic ReviewThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2017 (Nov 6); 30 (6): 1149-1169 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Benjamin Hidalgo, Toby Hall, Jean Bossert, Axel Dugeny, Barbara Cagnie, and Laurent Pitancea

Faculty of Motor Sciences at Université Catholique de Louvain-La-Neuve,

Louvain, Belgium

Objective: To review and update the evidence for different forms of manual therapy (MT) and exercise for patients with different stages of non-specific neck pain (NP).

Data sources: MEDLINE, Cochrane-Register-of-Controlled-Trials, PEDro, EMBASE.

Method: A qualitative systematic review covering a period from January 2000 to December 2015 was conducted according to updated-guidelines. Specific inclusion criteria only on RCTs were used; including differentiation according to stages of NP:(acute – subacute [ASNP] or chronic [CNP]),

as well as sub-classification based on type of MT interventions:

MT1 (HVLA manipulation);

MT2 (mobilization and/or soft-tissue-techniques);

MT3 (MT1 + MT2); and

MT4 (Mobilization-with-Movement).

In each sub-category, MT could be combined or not with exercise and/or usual medical care.Results: Initially 121 studies were identified for potential inclusion. Based on qualitative and quantitative evaluation criteria, 23 RCTs were identified for review.

Evidence for ASNP (subacute neck pain):

MODERATE-evidence: In favour of(i) MT1 (HVLA manipulation) to the cervical spine (Cx) combined with exercises when compared to MT1 to the thoracic spine (Tx) combined with exercises;

(ii) MT3 (= MT1 + MT2) to the Cx and Tx combined with exercise compared to MT2 to the Cx with exercise or compared to usual medical care for pain and satisfaction with care from short to long-term.

Evidence for CNP: (chronic neck pain):

STRONG-evidence: Of no difference of efficacy between MT2 at the symptomatic Cx level(s) in comparison to MT2 on asymptomatic Cx level(s) for pain and function.

MODERATE to STRONG-evidence: In favour of MT1 and MT3 on Cx and Tx with exercise in comparison to exercise or MT alone for pain, function, satisfaction with care and general-health from short to moderate-terms.

MODERATE-evidence: In favour(i) of MT1 (HVLA manipulation) as compared to MT2 and MT4, all applied to the Cx, for neck mobility, and pain in the very short term;

(ii) of MT2 (mobilization and/or soft-tissue-techniques) using soft-tissue-techniques to the Cx and Tx or MT3 (= MT1 + MT2) to the Cx and Tx in comparison to no-treatment in the short-term for pain and disability.Conclusion: This systematic review updates the evidence for manual therapy (MT) combined or not with exercise and/or usual medical care for different stages of neck pain (NP) and provides recommendations for future studies. Two majors points could be highlighted, the first one is that combining different forms of MT with exercise is better than MT or exercise alone, and the second one is that mobilization need not be applied at the symptomatic level(s) for improvements of NP patients. These both points may have clinical implications for reducing the risk involved with some MT techniques applied to the cervical spine.

Keywords: Manual Therapy; evidence based practice; exercise; musculoskeletal manipulation; neck pain; systematic review.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Non-specific neck pain (NP) is defined as pain in the posterior and lateral aspect of the neck between the superior nuchal line and the spinous process of the first thoracic vertebra with no signs or symptoms of major structural pathology and no or minor to major interference with activities of daily life as well as with the absence of neurological signs and specific pathologies; such as: traumatic sprain and fracture, tumour, infectious or inflammatory cervical spondylolysis, etc. [72–80] It accounts for around 25% of all outpatient visits to physiotherapy [72–75] with a life-time incidence rate of 12 to 70% among the general population [73, 76–80], although men are less likely to be affected than women. [79, 81–84] Most people with NP do not experience a complete resolution of symptoms with 50–85% reporting recurrence 1 to 5 years later. [80]

Consequently, NP results in enormous health-costs in terms of treatment, lost wages and work absenteeism. [78, 81, 84] Despite its major prevalence and socioeconomic consequences, NP is the “poor cousin” to low back pain in terms of research investigation. [77, 78] In most cases a specific diagnosis cannot be made and NP is labelled non-specific, because of the multifactorial etiology. [80, 81, 85, 86]

Within a “Bio-Psycho-Social” framework, a number of factors could be considered to contribute to NP. These include non-modifiable risk factors related to patho-anatomical features (e.g. history of trauma, age, gender and genetics) and adjustable risk factors, which are more related to psychosocial features (e.g. smoking, physical activity and sedentary life style, beliefs, coping style, expectations, and work satisfaction). These factors may also contribute to the transition from acute to chronic pain status. [79, 80–82, 86, 87]

Conservative treatments used to help manage NP are numerous and include usual medical care (UMC: i.e. face to face interview, education, reassurance, medication, ergonomic and stay active advice), various forms of exercise, massage, and acupuncture among others, but there is a lack of evidence regarding their relative efficacy. [76, 78, 80] Manual therapy (MT) is also an increasingly popular treatment available to people with NP and many countries include MT in national guidelines for treating musculoskeletal disorders. [79, 88, 89] In general terms, these treatments are considered to be more useful than no intervention or placebo treatments. [72, 76, 80–82, 85, 88] MT includes both passive techniques (hands-on) and active techniques (hands-off) and should be used within a clinically reasoned and evidence-based-practice framework. [89–91] The aim of MT in the context of NP is to decrease pain, improve movement, motor control, and function and thereby reduce disability. [79, 88–91]

A recent systematic review (SR) from Hidalgo et al. [91] examined the efficacy of different common forms of MT for low back pain which had been reported in the literature or used in clinical practice. In that review, three categories of MT were identified and their efficacy examined according to specific inclusion criteria (both qualitative and quantitative). These categories were MT1 comprising high velocity low amplitude thrust manipulation (HVLA), MT2 comprising a range of spinal mobilization and/or soft-tissue-techniques, MT3 being MT2 combined with MT1. All categories could be combined or not with exercise (general or specific) and/or with UMC. [91] In addition to these forms of MT, mobilization-with-movement (MWM; i.e. MT4) is an increasingly popular form of treatment used clinically for a range of musculoskeletal disorders and receiving increasing research attention. [92, 93]

This type of rigorous systematic review of different forms of MT combined or not with exercise and compared with UMC has not yet been reported for NP. For example, previous reviews have reported that MT is more effective than a placebo treatment or no treatment at all for NP, but failed to establish levels of evidence for other forms of treatment such as UMC or exercise in comparison to MT. Moreover, these studies have not adequately investigated which MT approach when combined with UMC or exercise, is more effective for NP. [75, 88, 94] However, the number of studies investigating MT for NP has recently increased, possibly in part due to its popularity and use in clinical practice. Hence, there are a number of recently published trials that have not been considered in previous SRs of NP. [75, 94, 96–100]

Further, the SRs published to date on NP, are not up to date, rarely focus on NP in isolation (more often including headache, radiculopathy, and whiplash) have not considered low risk of bias studies (methodological quality ≥ 7/11 on the Cochrane checklist), and did not perform comprehensive analysis based on MT classification combined or not with UMC and/or exercise to establish the strength of the evidence. Thus, the aim of this SR is to inform clinicians, patients and policy makers of the best current evidence for a clinical-informed approach of the use of MT for NP, because there is a need for an updated and comprehensive SR on MT efficacy for NP.

Methods

This SR was conducted in accordance with the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group (CCBRG) and PRISMA updated guidelines for SR [95, 101] and is based on the methodology and design of a previous qualitative-SR. [91]

Search strategy

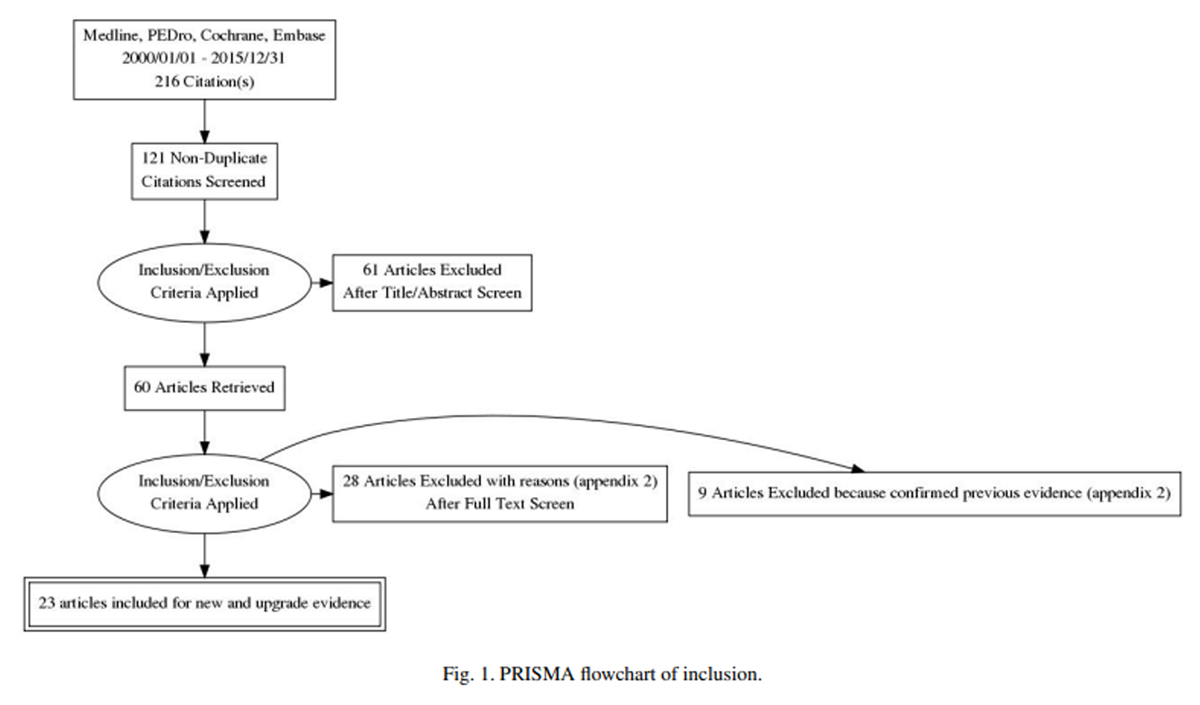

Figure 1 A literature search of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in English between 1st January 2000 and 31st December 2015, on the efficacy of MT in the treatment of NP was conducted by two reviewers in four electronic databases: MEDLINE (PUBMED), Cochrane-Register-of-Controlled-Trials (CRCT), Physiotherapy-Evidence-Database (P-EDro), EMBASE. The detailed search strategy in MEDLINE is presented in Appendix 1, and was adapted to search in the other databases. Based on information revealed in the titles and abstracts, a first selection of articles was performed using the inclusion criteria based on consensus between experts (i.e. authors). A final selection was conducted after critical appraisal of the quality of the studies. A consensus was reached at each step (Figure 1) on the studies to be included.

Inclusion criteriaStudy design RCTs were included only (i) if they presented a low-risk of bias, (ii) if subjects with NP were randomly allocated to receive either MT or a comparator group receiving “no-treatment”, a placebo procedure, or another usual conservative therapy for NP, (iii) if the randomization methods were appropriate and clearly reported, and (iv) if a single (assessors blinded) or double-blind design (assessors and patients blinded) was used.

Patients NP was differentiated on the basis of duration of the pain episode, with acute pain < 6 weeks, subacute pain 6–12 weeks, and chronic pain > 12 weeks. We also used a combination of duration, location, and signs/symptoms to determine the study population. [80, 91] Studies were included if the patients were male or female aged between 18 and 60 years suffering from acute-subacute (0–12 weeks) or chronic ( > 12 weeks) NP. Acute and subacute categories were combined because of their similarities in contrast to chronic NP category, where psychosocial factors appear more important. No mixed populations of combined acute-subacute and chronic NP were allowed. NP was required to be localized to the posterior neck between the superior nuchal line and the spinous process of the first thoracic vertebra. [75, 102] NP is often associated with cervicogenic headache and/or tension type headache, or with peripheral neuropathic pain in the upper limbs; these clinical categories of patients were not included in the present SR.

With respect to severity, NP is also classified according to a 4–grade classification system of the Neck Pain Task Force [102], and for this SR, only RCTs with a population comprising NP grade I or II on this classification system were selected, i.e. no signs or symptoms of major structural pathology and no or minor (I) to major (II) interference with activities of daily life with the absence of neurological signs.

Interventions

As manual therapy (MT) interventions are broad by nature, we decided to use a clinical sub-classification system of MT in this SR with four major categories of MT techniques. [91] Moreover, this sub-classification was in accordance with a comprehensive evidence based search strategy and the MT treatment used and reported in the intervention group (IG) of included RCTs.MT1 corresponds to spinal manipulation, where a HVLA thrust with “cavitation” is applied to the cervical spine (Cx) or thoracic spine (Tx). [103–105]

MT2 includes a range of mobilization techniques applied to the Cx or Tx which includes: low-velocity-mobilization such as physiological or accessory mobilization, articular muscle-energy-technique (MET, i.e. segmental analytic myotensive mobilization of Cx and Tx) and/or the soft-tissue techniques (STT) including “myofascial-release”, “trigger-points” “muscular-MET” (i.e. analytic myotensive techniques on specific muscles using “contract-relax” neurophysiological principles) of the neck region. [82, 91, 103, 106]

MT3 comprises the combination of MT2 and MT1. [103, 105, 106]

MT4 corresponds to mobilization-with-movement (MWM) with cervical sustained-natural-apophyseal-glides (SNAGs) developed by Mulligan. [107, 108]

Furthermore, as modern MT include hands off approach, sub-categorization of groups MT1-4 was based on the addition or not of exercise either specific (for example based on directional-preference, strengthening/ stabilization of specific deep-neck and scapular muscles, and motor control) or general (for example: range of motion exercises of the head and neck, sitting posture correction) or usual-medical-care (UMC; i.e. face to face interview, education, reassurance, medication, ergonomic and stay active advice). [91, 94, 104, 38–41]

Control groups

The control groups received: “no treatment”, a placebo, or another usual conservative treatment for NP (e.g. UMC, exercise, electrotherapy, physiotherapy, or rehabilitation). [95, 101, 41]

Outcome measures of effectiveness

Tables 1–3

page 5+The outcome measures were classified according to the CCBRG recommendations: pain, function, overall-health and quality of life (see Appendix 1). Timing of the follow-up measurements was defined as very-short-term (end of treatment/discharge to 1 month), short-term (1–3 months), intermediate-term (3 months–1 year), or long-term (1 year or more).

Quality assessment Two independent reviewers (JB and AD) assessed risk of bias, methodological quality, data extraction and clinical relevance of each trial. Quantitative and qualitative criteria were assessed by applying the CCBRG criteria. [95, 101] Quantitative risk of bias was assessed, using an 11–point check-list (see Appendix 1).

Qualitative assessments were made on the basis of the following criteria: a well determined distinction and separation between combined acute-subacute and chronic NP categories at baseline, a detailed description of MT intervention and the possibility that reviewers would be able to classify the MT techniques according to MT1-MT4 classification system, and a single-blind or double-blind RCT design.

Included studies were required to be low-risk of bias. We considered as “high-quality” those RCTs with single-blind (assessors blinded) or double-blind (patients and assessors blinded) designs that met at least 9/11 of CCBRG criteria indicated by an ‘A’. “Moderate quality” RCT status was assigned to studies of single-blind design with a minimum score of 7/11 indicated by a ‘B’ (Tables 1 and 2). [75, 91] To reduce the number of words and the number of studies included in this SR, only RCTs that present new findings or update/upgrade previous evidence from SRs with our methodology are fully described in the results section and Tables 1–3. However, all studies from our search strategy, as well as reason of exclusion are presented in the Appendix 2.

Strength of evidence and clinical relevance Strength of evidence was determined by grouping similar “Patients Interventions Comparisons Outcomes Study Design” to provide an overall level of evidence (see Appendix 1 for the process of evidence) on the efficacy of the 4 categories of MT (MT1-MT4) combined or not with another intervention. Conclusions of evidence are summarized in Table 3.

The effect size was independently collected or calculated by two authors, and used to assess the clinical relevance of MT interventions in outcome measures. We reported the between groups means of difference (MD = mean A – mean B) or Cohen’s standardized means of difference (SMD = mean A – mean B/mean SD). In this SR, the clinical relevance was determined by two conditions and scored by “YES” in favour of the intervention group; if there were (i) significant differences between groups (p < 0.05) associated (ii) with between groups effect sizes equal or superior to the minimal clinically important difference for MD or moderate for SMD (from 0.4–0.8) to large SMD (from 0.8–1.2) and very large SMD ( > 1.2) effects on specific outcome measures (Tables 1 and 2). [91, 95]

Results

Two reviewers performed the selection of articles (Fig. 1). A qualitative SR was undertaken on the 23 low-risk of bias RCTs, based on the qualitative and quantitative criteria described above; 21 studies were classified as level A and 2 as level B quality (Tables 1 and 2). Summary findings are shown in Table 3, which includes a presentation of the level of evidence drawn from the selected RCTs.

Effects of interventions on acute-subacute NPMT1 to the cervical spine with exercise versus MT1 to the thoracic spine with exercise Puentedura et al. [42] evaluated the efficacy of MT1 to the upper Cx in comparison to MT1 on the Tx. Both interventions were combined with the same exercise (ROM exercises of the head and shoulder, and upper limb exercise against moderate resistance elastic band’s). The numbers of treatment sessions were similar in both groups (n = 5). There were statistically significant and clinically relevant improvements for pain (p < 0.005 and SMD > 2) and disability (p < 0.05; SMD > 1) from 1 week to 6 months, and for quality of life at 6 months (p < 0.005 and SMD of 1.14) for patients who received MT1 to the Cx combined with exercise. However, in both groups (7% in the cervical group and 70% in the thoracic group) minor treatment side effects were reported such as increases in NP, headache and fatigue that resolved within 24 hours. The authors concluded that those patients might benefit more from MT1 to the Cx than Tx.

MT1 with electro/thermal-therapy versus electro/thermal-therapy alone Gonzalez-Iglesias et al. [72, 43] investigated in two studies the efficacy of MT1 (localized to the upper Tx) combined with electro/thermal-therapy as compared to electro/thermal-therapy alone for acute-subacute NP patients. The number of sessions was equivalent in both groups and both studies covered 5–6 sessions over 3 weeks. There were statistically significant improvements for pain (p < 0.001 and SMD > 2), disability (p < 0.001 and SMD > 2.6) and cervical range-of-motion (CROM). The authors concluded that the combined intervention provided clinically greater improvement on all outcome measures.

Comparison of two MT2 interventions Nagrale et al. [86] evaluated comprehensive MT2 (STT) that combined muscular-MET, trigger (ischemic compression) and tender-points (strain-counterstrain) techniques on the trapezius in comparison to simple MT2 (STT) that included only the muscular-MET on the trapezius for acute-subacute NP patients. At 2 and 4 weeks follow-up, the results showed significant improvements in both groups on pain reduction, function and side-bending. However, there was a significant clinically relevant difference between groups with large effect sizes for pain and function (SMD for CROM lateral flexion > 2, for VAS > 1.1, and for NDI > 0.8) at follow-up (2–4 weeks) in favour of the comprehensive MT2 intervention.

MT2 versus sham-Ultrasound (SUS) Blikstad and Gemmell [44] and Gemmell et al. [45] compared the effect of MT2 (STT) consisting of trigger point techniques to the trapezius muscle (ischemic compression and trigger point release) to SUS for acute-subacute NP. The results demonstrate that MT2 had an immediate effect on pain compared to SUS. However, in both studies, no statistically significant differences were apparent for any outcome measures between the groups.

MT3 versus usual-medical-care and home exercise Bronfort et al. [46] studied the efficacy of MT3 (on hypomobile Cx and Tx segments and on STT) as compared to UMC (private consultation and education combined with medication (AINS, narcotic drugs and/or muscle relaxants, and advice to stay active) and to home exercise (2 × 1 hours of education for flexibility and strengthening exercise of the head and shoulder) for acute-subacute NP. Short and long-terms analyses showed improvement for pain at 12 weeks and 52 weeks (p < 0.005 and SMD > 0.5) in favour of the MT3 as compared to UMC, but not for MT3 over home exercise or home exercise over UMC. No serious adverse events were reported in the study. However, 40% in the MT3 group and 46% in the home exercise group reported musculoskeletal pain, and 60% in the UMC group reported gastrointestinal symptoms and drowsiness.

The authors concluded that MT3 and home exercise interventions led to similar short- and long-term outcomes, but participants who received UMC seemed to fare worse, with a consistently higher use of pain medication during the study period. Leininger et al. [97] in a secondary analysis of this study explored the relationship between satisfaction with care (information and general care, on 0–100 scale) using a multidimensional instrument [47], neck pain (VAS), and global satisfaction with care (scale). Differences in satisfaction with specific aspects of care were analyzed using a linear mixed model at 12 and 52 weeks. Individuals with acute/subacute NP were more satisfied with specific aspects of care received during spinal MT3 or home exercise interventions compared to UMC.

MT3 with exercise versus MT2 with exercise Masaracchio et al. [48] compared the effect of MT3 during two sessions (2 × HVLA targeted to T1–T3 and to T4–T7 combined with MT2 on the Cx in a supine position with accessory mobilization over the spinous processes from C2–C7) and home exercise (active Cx rotation ROM exercise), to MT2 (the same as above) and home exercise for acute-subacute NP patients. The results demonstrated significant differences in terms of pain (p < 0.001 and SMD of 0.96) and disability (p < 0.001 and SMD of 1.11) at one week in favour of the MT3 with exercise group. The authors concluded that the combination intervention led to better clinical short-term improvement in all outcome measures.

MT2 with exercise and MT4 with exercise versus exercise alone Ganesh et al. [96] studied the effect of MT2 (accessory mobilization on the Cx for 10 sessions over 2 weeks) with exercise (flexibility and strengthening of cervical and scapular muscles, and cervical ROM exercises) in comparison to MT4 (SNAGs applied to the Cx in a sitting position) with exercise and exercise alone for patients with acute-subacute NP. All groups were instructed to continue the exercise at home for 4 weeks. The results demonstrated that all the groups improved overtime compared to baseline (p < 0.05). However no significant differences between groups (p > 0.05) were determined for all outcome measures (pain, disability, CROM) with very small effect size between groups (SMD = 0.2) after intervention and at follow-up. Any adverse events were reported in the study. The authors concluded that supervised exercises are as effective as both combined mobilizations and exercises on all outcome measures. However as 30–70% of acute NP patients improve spontaneously overtime; future studies should include a UMC group to analyse change with respect to the natural resolution of NP over time.

Effects of interventions on chronic NPMT1 in comparison to MT2 and MT4 Izquierdo-Pérez et al. [49] compared three different treatments applied to the Cx. These were HVLA (MT1), accessory mobilization (MT2) and SNAGs (MT4). Each patient received 4 sessions within 2 weeks. All three groups showed similar improvements in pain, disability and ROM but there was no difference between interventions in any outcome measure apart from CROM in extension (p < 0.01 and MD > 8.3) in favor of MT1 in comparison to MT4. No adverse events were reported for any intervention.

Lopez et al. [50] also studied the effect of the same three interventions applied to the Cx, i.e. HVLA (MT1), accessory mobilization (MT2) and SNAGs (MT4) and CROM. In comparison to Perez’ investigation [49], each patient received only one single therapy session. All of the treatments groups demonstrated similar efficacy for the management of pain (at rest, flexion/extension, rotation, side bending, pressure pain thresholds on C2), and CROM (multidirectional). However, only one significant difference (two way; treatment x time interaction, p = 0.04) between groups on all outcome measures was demonstrated with respect only for pain at rest in favor of MT1 and MT2 groups over the MT4 group with moderate to large effects size. There was also an interaction found between trait anxiety (all participants completed the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; an introspective psychological self-report measure of anxiety affect), improvement in pain and technique applied, i.e. high anxiety levels expected better prognosis (prospect of recovery) outcome after MT2 application and low anxiety levels expected better prognosis after MT1 and MT4 application. Authors did not report adverse events.

Authors of both studies. [49, 50] concluded by saying that all 3 techniques applied to the Cx were effective in the management of chronic NP with no differences between them. However, MT1 appears marginally better than other forms of MT based on improved CROM in extension only and pain at rest. [49, 50]

MT1 to the cervical spine versus kinesio-Tape Saavedra-Hernandez et al. [51] compared one group receiving MT1 (HVLA thrust to the mid-Cx and upper-Tx), to another group receiving only Kinesio-Tape applied to the neck for one week in patients with chronic NP. Both interventions demonstrated similar decreases in pain, disability and increases in CROM over the 1–week study period but the results showed that there were no statistically significant differences between both groups in all outcome measures except for the CROM in rotation at 7 days. Five patients reported minor adverse events with 3 (7.5%) in the manipulation group (minor increase in NP or fatigue) and two (5%) in the Kinesio-Tape group (cutaneous irritation related to the tape application). These minor post-treatment symptoms resolved within 24 hours. The authors concluded that the application of MT1 or Kinesio-Tape leads to similar reduction in pain and disability and increases in CROM, and that concerning CROM and disability, the changes were not clinically meaningful.

MT1 to the cervical spine versus MT1 to the thoracic spine Martinez-Segura et al. [52] studied the relative efficacy of a single session of MT1 to the mid-Cx or to the upper-Tx for patients with chronic NP. All groups showed similar changes (p < 0.001), but there were no significant differences between the 3 groups on all outcome measures (neck pain intensity with NPRS, CROM, pressure pain threshold with algometry). Two patients reported some minor side effects. The authors concluded that Cx and Tx spine MT1 induced similar changes in outcome measures.

MT versus << no-treatment >> Sherman et al. [76] investigated the effectiveness of MT2 (STT to the Cx and Tx region, i.e. connective tissue massage, ischemic compression, myofascial release) in comparison to “no treatment” with a self-care booklet for patients with chronic NP. Differences between both groups were statistically significant for pain (p < 0.005) and disability (p < 0.05) at 4–weeks of treatment. The authors concluded that MT2 is safe (i.e. no serious adverse effects were reported) and may have clinical benefits for treating chronic NP at least at short-term.

Schwerla et al. [82] compared MT3 to Cx and Tx combined with SUS to “no treatment” with SUS alone for chronic NP patients. The results showed clinical relevant differences in favour of the intervention group on pain reduction (p < 0.009 and MD of 1.8), overall health-improvements (p < 0.019 and MD of 14.6) and functional-status (p < 0.05 and MD of 9) during the course and completion of treatment.

MT1 with infrared radiation therapy (IRT) and exercise versus IRT and exercise alone Lau et al. [79] assessed the effectiveness of MT1 to the Tx combined with IRT (15 minutes over the painful site) and exercise (active neck mobilization, isometric neck muscle contraction for stabilization, and stretching of trapezius and scalene muscles) in comparison to a control group (IRT and exercise only) for chronic NP patients. This study showed that patients in the experimental group had clinically relevant improvements in NP (p < 0.001 and SMD of 0.65) at 6 months and for function (p < 0.004 and SMD of 0.5), overall health (p < 0.001 and SMD of 0.83) and neck mobility (p < 0.05) at 3 months when compared to the control group from the completion of treatment up to a 3 to 6 months follow-up.

MT2 on symptomatic spinal level(s) versus “sham” MT2 (random location) Kanlayanaphotporn et al. [53] studied the immediate effects of MT2 (Cx accessory mobilization) on pain and active CROM. In the experimental group, the treatment details including the spinal level(s) to be treated, the grade of movement to be applied, and the most appropriate technique of mobilization were noted. In the control group, the patients received one of the following mobilization techniques that could be considered as a placebo procedure: a central PA, ipsilateral unilateral PA, or contralateral unilateral PA pressure. In both groups the MT2 intervention was applied for 1 minute repeated twice. Both group showed significant decrease in neck pain at rest and in pain at most painful movement. However, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups on pain and active CROM.

Aquino et al. [90] and Schomacher et al. [54] evaluated whether MT2, using the same techniques as described above for Aquino et al., and intermittent translatory traction in supine (accessory mobilization) between C2 and C7 for Schomacher et al., applied both to the symptomatic Cx level, was able to reduce pain compared to the same MT2 interventions but at an asymptomatic Cx level(s). Although all groups in both studies showed significant immediate pain relief, there was no significant difference between the groups.

These studies [90, 53, 54] demonstrate that identification of the symptomatic Cx segment is not important for the immediate effects of MT2 (accessory mobilization) on pain for chronic NP.

MT versus active rehabilitation Bronfort et al. [78] compared MT3 alone (HVLA thrusts with STT) to the Cx and Tx for 20 sessions of 15–20 minutes), to MT3 with exercise (neck and upper body strengthening for 20 sessions of 1 hour), to MedX Exercise (high technology devices for strengthening of the neck and upper-body during 20 sessions of 1 hour). Although there was a tendency for greater improvement for the two exercise groups (MT3 with exercise and MedX exercise), the efficacy of these 3 interventions was not statistically different for pain, function and overall improvement during treatment. However, at 1–year follow-up, there were significant differences in favour of MT3 combined with exercise and MedX exercises groups as compared to MT3 alone on pain reduction (p < 0.05 and SMD > 0.4). The MT3 with exercise, however, showed greater gains in all measures of performance (strength, endurance, and CROM) than MT3 alone (p < 0.05), as well as a greater satisfaction with care (p < 0.01). After a 1–year follow-up, the authors concluded that MT3 with exercises and MedX exercise appeared to be more efficient than MT3 alone for chronic NP.

Evans et al. [55] investigated the efficacy of MT1 (to the Cx and Tx for 20 sessions of 15–20 minutes) combined with high dose (20 sessions of 1–hour) supervised strengthening exercise (neck and upper body strengthening), to high dose supervised strengthening exercise alone, and low dose home exercise and advice for chronic NP patients. There were clinically relevant improvements at 12 weeks for both high dose exercise groups for pain and overall health improvement (p < 0.001) in comparison to home exercise and a trend for disability for MT1 combined with exercise against home exercise. The authors concluded that high dose exercise combined or not with MT1 gained better outcomes than home exercise particularly in the medium-term (3 months).

Akhter et al. [98] investigated the role of MT1 (HVLA on the stiff Cx segments for around 6 sessions over 3 weeks) combined with supervised exercise (flexibility, strengthening of the cervical and scapular muscles and CROM exercise) in comparison to supervised exercise regime alone for chronic NP patients. At the end of 3 weeks interventions both groups were instructed to do the same exercise for a period of 3 months on a daily basis. Both groups made significant improvement in pain and functional outcome measures (p < 0.001) over 3 and 12 weeks’ time period in relation to baseline. However, between groups analysis showed no significant differences at all time points for both outcome measures (p > 0.05). Adverse events were reported for one subject with episode of dizziness, he was excluded from the study. Authors concluded that both groups made significant improvements and that on closer inspection MT1 with exercise appeared as a favourable treatment preference (a better trend of improvements) compared to exercise alone.

The general trend of these three studies [78, 98, 55] was that combined MT1 and MT3 on the Cx and Tx with exercise demonstrated better results for pain, function, satisfaction with care and general health in comparison to exercise or MT alone for patients with chronic NP.

Discussion

The goal of this SR was to assess and update the best evidence by including only low-risk of bias RCTs reporting on the effectiveness of different MT approaches, classified into 4 categories (MT1-MT4), in the management of NP without associated disorders such as cervicogenic headache or radiculopathy. Efficacy for MT1-4 interventions was assessed in isolation or when combined with exercise or UMC.

With respect to acute/sub-acute NP this review found moderate evidence in favour of (i) MT1 at the involved Cx level combined with exercise when compared to MT1 to the Tx combined with exercise [42]; (ii) MT3 (Tx HVLA + Cx accessory mobilization) combined with exercise compared to MT2 (Cx accessory mobilization) with exercise [49]; (iii) MT1 to the upper Tx combined with electro/thermal-therapy in comparison to electro/thermal-therapy alone, for pain relief and functional improvement in the very short to short-term; (iv) MT3 to the Cx and Tx or home exercise in comparison to UMC for pain and satisfaction with care from short to long-term [97, 46]; (v) MT2 (STT) comprising muscular-MET, trigger-points (ischemic compression), and positional-release (tender-points) techniques to the trapezius compared to MT2 (STT) using only muscular-MET to the trapezius for pain, function and CROM in the very short-term. [86]

This review found moderate evidence of no difference in efficacy between MT2, comparing trigger point therapy to SUS. [44, 45] In addition there was limited evidence of no difference in efficacy between MT2 (Cx accessory mobilization) with exercise in comparison to MT4 (Cx SNAGs) combined with exercise in comparison to exercise alone on pain, disability and CROM. [50]

With respect to chronic NP this review found strong evidence of no difference in efficacy for MT2 when comparing Cx accessory mobilization at the symptomatic level to the asymptomatic level for pain and function. [90, 53, 54] Moderate to strong evidence was found in favour of MT1 and MT3 at the Cx and Tx combined with exercise in comparison to exercise or MT alone for pain, function, satisfaction with care and general health at least in the short- to moderate-terms. [78, 98, 55] Moderate evidence was found in favour (i) of MT1 compared to MT2 (Cx accessory mobilization) and MT4 (Cx SNAGs), for CROM [49] and pain [50] in the very short-term; (ii) of MT2 (STT to the Cx and Tx) [76] and MT3 to the Cx and Tx [82] in comparison to no-treatment (self-care booklet or SUS), in the short-term for pain and disability [76]; (iii) of MT1 to the Tx with IRT and exercise as compared to IRT and exercises alone for pain, function, overall-health and CROM in the short to moderate-term. [79] Moderate evidence was found of no difference (i) between MT1 to the Cx and Cx-Tx in comparison to Kinésio-Tape applied to the neck region for pain, disability and CROM in the very short-term [51]; (ii) between MT1 to the Cx in comparison to MT1 to the Tx for pain, CROM and pressure pain threshold at the very short-term. [52]

The evidence from this current SR is consistent with evidence provided from previous systematic reviews [75, 94, 56] reporting on the efficacy of MT for NP. However, the current review provides new evidence in this regard, as well as improves understanding of the levels of evidence for manual therapists. Due to the very large body of evidence regarding MT for NP, and the inability to present all this information in a single paper, we focused on RCT’s with low-risk of bias that would update and improve on previous reviews. This new evidence and confirmation of previous reviews can be seen in summary in Table 3.

This review provides manual therapists with information about treatment efficacy covering a wide range of commonly used MT in everyday clinical practice. Rather than combining all MT into a single comparison group we sub-categorized MT into 4 distinct groups combined or not with exercise. This enables the reader to better understand the evidence for different forms of MT and whether the addition of exercise improves treatment efficacy.

Adverse events

In addition to understanding the evidence for the efficacy of MT it is important to recognize any potential risks associated with MT intervention. This is particularly true for the cervical spine, which has a special vulnerability due to its unique anatomy and proximity to the brain. In the literature, MT to the cervical spine is often associated with adverse events particularly with regard to HVLA thrust techniques. Adverse events are important, not only from a morbidity/injury perspective, but also in terms of patient satisfaction and perception of improvement following treatment, which might be decreased in patients who experience adverse events. [57] In general however, there is a lack of consensus in reports of RCT’s regarding the classification and definition of adverse events following interventions. When adverse events have been reported we have described these adverse events for each included study in the result section. Future studies should follow more rigorous and standardized methods to allow more effective comparisons. [58–65]

Clearly, a way to prevent adverse events is not to perform cervical manipulation, and perhaps manipulate the thoracic spine instead. It is suggested that thoracic manipulation may have some efficacy in the treatment of neck pain. [75] However, there is moderate evidence favouring cervical over thoracic manipulation for acute NP. [42] Combining cervical mobilization with thoracic manipulation may be one way to bypass the risks involved with certain cervical techniques and also improve treatment efficacy. [48] In chronic NP, although moderate evidence was found in favour of cervical manipulation when compared to accessory mobilization or SNAGs to the cervical spine [49, 50], reported differences were marginal for Cx extension ROM only as well as pain at rest. Furthermore, there is moderate evidence of no difference between cervical and thoracic spinal manipulation at least in terms of immediate effects. [52] Hence, it is important to assess whether such small marginal improvements in outcome favouring Cx manipulation can be justified against the risks involved. Due to the rarity of serious adverse events following cervical MT techniques [66], it is virtually impossible to clearly identify the risk benefit analysis of Cx manipulation. Further investigation is required to compare a cervical and thoracic spine treatment approach against cervical manipulation alone, as well as the long-term effects. Meanwhile, we recommend the guidelines from a consensus of experts (http://www.ifompt.org) for cervical spine screening along with the evidence from this SR before applying HVLA thrust techniques to the Cx for patients with NP.

NP classification

To our knowledge, and in contrast to LBP, there are no recommended or validated classification systems to stratify NP and to target specific subgroups with OMT treatment formulated for each subgroup. Classification of patients with LBP into sub-groups and the application of specific OMT interventions for each matched sub-group has proved to be more effective than generic forms of treatment. [67–71]. Consequently, stratified care for LBP is becoming a dominant topic in research and clinical practice. [91, 68, 71]

Due to the lack of classification systems for NP, the treatment decision to apply a specific form of MT (MT1-4) and/or exercise is mainly based on clinical reasoning, which must include the subjective and physical examination. Firstly, the subjective examination should help to identify and exclude people with psychosocial issues (yellow flags) and serious spinal pathologies (red flags). [69] Secondly, the dominant pain mechanism should be identified, and can be broadly divided into three categories. These categories are the “input mechanisms” corresponding to nociceptive pain and peripheral neuropathic pain; the “processing mechanism” defined as centrally maintained pain associated with central sensitization, and the cognitive-affective mechanisms of pain; the “output mechanisms” include the autonomic, motor, neuroendocrine and immune systems. [69–71] Thirdly, therapeutic goals and OMT treatment options can be determined from the integration of the subjective and physical examination. [69–71]

Limitations

The results of our qualitative SR should be interpreted in the light of some limitations. First, although only low-risk of bias RCTs were include, there was much heterogeneity among trials; including the way the trial data was presented, the patients, comparison (control) groups (and co-interventions), outcomes measures, and studies’ design, as well as the report of adverse events. Secondly to identify which MT intervention should be evaluated, we used an original and comprehensive classification system in accordance with a comprehensive analysis of the literature as well as with clinical practice of MT. This classification system was used in a previous SR of MT for low back pain. [91] However, there is currently no ideal classification of MT techniques as MT is broad by nature. The MT2 category may be seen as the weakest category in this classification system, as it comprises a very wide range of mobilization techniques as well as articular MET and/or STT. For this reason we described throughout the text and tables the specific interventions used in RCT’s investigating MT2; attempting to improve understand of the efficacy of this MT approach for NP. Due to the heterogeneity among trials, a meta-analysis enabling pooled statistics of effect was not possible. Thirdly, some studies used adjuvant therapy in both intervention and comparison groups which create difficulties to evaluate objectively the intrinsic efficacy of MT. Finally, only studies published in English from 1st January 2000 to 31th December 2015 were reviewed, leading to the possibility of relevant articles existing in other languages or before 2000.

Conclusion

This SR has confirmed previous evidence and increased levels of confidence regarding efficacy of MT for NP. The clinical implications of this evidence can be broadly summarized to a number of points. Firstly, in general it can be seen that combining different forms of MT with exercise is better than MT or exercise alone. Secondly, there is moderate to strong evidence in favor of MT1 or MT3 combined with exercise for improvement in pain, function, and satisfaction with care for patients with NP when compared to UMC, exercise alone, MT alone or to no treatment. Thirdly, there is strong evidence that for chronic NP mobilization need not be applied at the symptomatic level for improvement in pain and function. This may have implications for reducing the risk involved with some MT techniques applied to the Cx as well as to choose the level(s) of Cx treatment in function of the irritability state of the patient. Fourthly, there is moderate evidence that in general MT1, MT2 and MT4 have similar effects on NP. Since intuitively Cx manipulation carries greater risk than mobilization or MWM these interventions could be seen as a viable option to manage NP together with exercise and in combination with Tx MT1. Future RCTs should be more rigorous in their investigation by not mixing categories of patients as well as intervention types.

Supplementary Material

Risk of bias assessment

Criteria list for methodological quality assessment from Cochrane Collaboration Back Review GroupA: Was the method of randomization adequate? Yes/ No/Don’t know.

B: Was the treatment allocation concealed? Yes/No/ Don’t know.

C: Were the groups similar at baseline regarding the most important prognostic indicators? Yes/No/ Don’t know.

D: Was the patient blinded to the intervention? Yes/No/Don’t know.

E: Was the care provider blinded to the intervention? Yes/No/Don’t know.

F: Was the outcome assessor blinded to the intervention? Yes/No/Don’t know.

G: Were cointerventions avoided or similar? Yes/ No/Don’t know.

H: Was the compliance acceptable in all groups? Yes/No/Don’t know.

I: Was the dropout rate described and acceptable? Yes/No/Don’t know.

J: Was the timing of the outcome assessment in all groups similar? Yes/No/Don’t know.

K: Did the analysis include an intention-to-treat analysis? Yes/No/Don’t know.

Operationalization of the criteria listA: A random (unpredictable) assignment sequence. Examples of adequate methods are computer generated random number table and use of sealed opaque envelopes. Methods of allocation using date of birth, date of admission, hospital numbers, or alternation should not be regarded as appropriate.

B: Assignment generated by an independent person not responsible for determining the eligibility of the patients. This person has no information about the persons included in the trial and has no influence on the assignment sequence or on the decision about eligibility of the patient.

C: In order to receive a “yes,” groups have to be similar at baseline regarding demographic factors, duration and severity of complaints, percentage of patients with neurologic symptoms, and value of main outcome measure(s).

D: The reviewer determines if enough information about the blinding is given in order to score a “yes”.

E: The reviewer determines if enough information about the blinding is given in order to score a “yes”.

F: The reviewer determines if enough information about the blinding is given in order to score a “yes”.

G: Cointerventions should either be avoided in the trial design or similar between the index and control groups.

H: The reviewer determines if the compliance to the interventions is acceptable, based on the reported intensity, duration, number and frequency of sessions for both the index intervention and control intervention(s).

I: The number of participants who were included in the study but did not complete the observation period or were not included in the analysis must be described and reasons given. If the percentage of withdrawals and dropouts does not exceed 20% for short-term follow-up and 30% for long-term follow-up and does not lead to substantial bias a “yes” is scored. (N.B. these percentages are arbitrary, not supported by literature).

J: Timing of outcome assessment should be identical for all intervention groups and for all-important outcome assessments.

K: All randomized patients are reported/analyzed in the group they were allocated to by randomization for the most important moments of effect measurement (minus missing values) irrespective of noncompliance and cointerventions.Conflict of interest

None to report.

References:

Gonzalez-Iglesias J, Fernandez-de-las-Penas C, Cleland JA.

Inclusion of thoracic spine thrust manipulation into an electro-therapy/thermal

program for the management of patients with acute

mechanical neck pain: A randomized clinical trial.

Man Ther 2009; 14: 306-13Cleland JA, Glynn P, Whitman JW, Eberhart SL, MacDonald C, Childs JD.

Short-term effects of thrust versus nonthrust mobilization/manipulation

directed at the thoracic spine in patients with neck pain: A randomized clinical trial.

Phys Ther 2007; 87: 431-40Jette AM, Smith K, Haley SM, Davis KD.

Physical therapy episodes of care for patients with low back pain.

Phys Ther 1994; 74: 101-10Vincent K, Maigne JY, Fischhoff C, Lanlo O, Dagenais S.

Systematic review of manual therapies for nonspecific neck pain.

Joint Bone Spine 2013; 80: 508-15Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Hawkes RJ, Miglioretti DL, Deyo RA.

Randomized trial of therapeutic massage for chronic neck pain.

Clin J Pain 2009; 25: 233-8Evans R, Bronfort G, Nelson B, Goldsmith CH.

Two-year Follow-up of a Randomized Clinical Trial of Spinal Manipulation

and Two Types of Exercise Patients With Chronic Neck Pain

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002 (Nov 1); 27 (21): 2383–2389Gert Bronfort DC, PhD; Roni Evans DC; Brian Nelson MD; Peter D. Aker DC, MSc; et al.

A Randomized Clinical Trial of Exercise and Spinal Manipulation

for Patients with Chronic Neck Pain

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001 (Apr 1); 26 (7): 788–797Lau HMC, Wing TT, Lam TH.

The effectiveness of thoracic manipulation on patients with chronic

mechanical neck pain – A randomized controlled trial.

Man Ther 2011; 16: 141-7Haldeman S, Carroll L, Cassidy JD, Schubert J, Nygren A.

The Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain

and Its Associated Disorders: Executive Summary

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008 (Feb 15); 33 (4 Suppl): S5–7Madson TJ, Cieslak KR, Gay RE.

Joint mobilization vs massage for chronic mechanical neck pain:

A pilot study to assess recruitment strategies and

estimate outcome measure variability.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2010; 33: 644-51Schwerla F, Bischoff A, Nurnberger A, Genter P, Guillaume JP, Resch KL.

Osteopathic treatment of patients with chronic non-specific

neck pain: A randomised controlled trial of efficacy.

Forsch Komplementmed 2008; 15: 138-45Hemmila HM.

Bone setting for prolonged neck pain: A randomized clinical trial.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2005; 28: 508-15Palmgren PJ, Sandstrom PJ, Lundqvist FJ, Heikkila H.

Improvement After Chiropractic Care in Cervicocephalic Kinesthetic

Sensibility and Subjective Pain Intensity in Patients

with Nontraumatic Chronic Neck Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2006 (Feb); 29 (2): 100–106Dziedzic K, Hill J, Lewis M, Sim J, Daniels J, Hay EM.

Effectiveness of manual therapy or pulsed shortwave diathermy in addition

to advice and exercise for neck disorders: A pragmatic

randomized controlled trial in physical therapy clinics. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 53: 214-22Nagrale AV, Glynn P, Joshi A, Ramteke G.

The efficacy of an integrated neuromuscular inhibition technique on

upper trapezius trigger points in subjects with

non-specific neck pain: A randomized controlled trial.

J Man Manip Ther 2010; 18: 37-43Pool JJ, Ostelo RW, Knol DL, Vlaeyen JW, Bouter LM, de Vet HC.

Is a behavioral graded activity program more effective than manual

therapy in patients with subacute neck pain? Results

of a randomized clinical trial.

Spine 2010; 35: 1017-24Martel J, Dugas C, Dubois JD, Descarreaux M.

A Randomised Controlled Trial of Preventive Spinal Manipulation

With and Without a Home Exercise Program for

Patients With Chronic Neck Pain

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011 (Feb 8); 12: 41Cleland JA, Childs JD, McRae M, Palmer JA, Stowell T.

Immediate effects of thoracic manipulation in patients with

neck pain: A randomized clinical trial.

Man Ther 2005; 10: 127-35Aquino RL, Caires PM, Furtado FC, Loureiro AV, Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML.

Applying joint mobilization at different cervical vertebral levels

does not influence immediate pain reduction in patients

with chronic neck pain: A randomized clinical trial.

J Man Manip Ther 2009; 17: 95-100Hidalgo B. Detrembleur C, Hall T, Mahaudens P, Nielens H.

The Efficacy of Manual Therapy and Exercise for Different Stages

of Non-specific Low Back Pain:

An Update of Systematic Reviews

J Man Manip Ther. 2014 (May); 22 (2): 59–74Konstantinou K, Foster N, Rushton A, Baxter D.

The use and reported effects of mobilization with movement techniques

in low back pain management; a cross-sectional descriptive

survey of physiotherapists in Britain.

Man Ther 2002; 7: 206-14Hidalgo B, Pitance L, Hall T, Detrembleur C, Nielens H.

Short-term effects of Mulligan mobilization with movement on pain,

disability, and kinematic spinal movements in patients with

nonspecific low back pain: A randomized

placebo-controlled trial.

J Manipulative PhysiolMiller J, Gross A, D'Sylva J, et al.

Manual Therapy and Exercise for Neck Pain: A Systematic Review

Man Ther. 2010 (Aug); 15 (4): 334–354van Tulder MW, Furlan AD, Bombardier C, Bouter L.

Update method guidelines for systematic reviews in

the cochrane collaboration back review group.

Spine 2003; 28: 1290-9Ganesh GS, Mohanty P, Pattnaik M, Mishra C.

Effectiveness of mobilization therapy and exercises

in mechanical neck pain.

Physiother Theory Pract 2015; 31: 99-106Leininger BD, Evans R, Bronfort G.

Exploring Patient Satisfaction: A Secondary Analysis of a

Randomized Clinical Trial of Spinal Manipulation, Home

Exercise, and Medication for Acute and Subacute Neck Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2014 (Sep 5); 37 (8): 593–601Akhter S, Khan M, Ali SS, Soomro RR.

Role of manual therapy with exercise regime versus exercise regime

alone in the management of non-specific chronic neck pain.

Pak J Pharm Sci 2014; 27: 2125-8Lopez-Lopez A, Alonso Perez JL, González Gutierez JL, et al.

Mobilization versus manipulations versus sustain apophyseal natural

glide techniques and interaction with psychological factors for

patients with chronic neck pain: Randomized controlled trial.

Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2015; 51: 121-32Beltran-Alacreu H, López-de-Uralde-Villanueva I, Fernández -Carnero J, La Touche R.

Manual therapy, therapeutic patient education, and therapeutic exercise,

an effective multimodal treatment of nonspecific chronic neck pain:

A randomized controlled trial.

Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2015; 94: 887-97Furlan AD, Malmivaara A, Chou R, Maher CG, Deyo RA, Schoene M, et al.

Updated method guideline for systematic reviews in

the cochrane back and neck group.

Spine 2015; 40: 1660-73Guzman J, Hurwitz EL, Carroll LJ, Haldeman S, Cote P, Carragee EJ, et al.

A New Conceptual Model Of Neck Pain: Linking Onset, Course, And Care

Results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on

Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008 (Feb 15); 33 (4 Suppl): S14–23Bronfort, G, Haas, M, Evans, RL, and Bouter, LM.

Efficacy of Spinal Manipulation and Mobilization for Low Back Pain

and Neck Pain: A Systematic Review and Best Evidence Synthesis

Spine J (N American Spine Soc) 2004 (May); 4 (3): 335–356Cleland JA, Fritz JM, Kulig K, Davenport TE, Eberhart S, Magel J, et al.

Comparison of the effectiveness of three manual physical therapy techniques

in a subgroup of patients with low back pain who satisfy a clinical

prediction rule: A randomized clinical trial.

Spine 2009; 34: 2720-9Di Fabio RP.

Efficacy of manual therapy.

Phys Ther 1992; 72: 853-64Bronfort G.

Spinal manipulation: Current state of research and its indications.

Neurol Clin 1999; 17: 91-111Mulligan B.

“Nags”, “Snags”, “MWMS” etc. 4 ed.

Welligton, New Zealand: Plane View Services Ltd; 1999.Hing W, Hall T, Rivett D, Vicenzino B, Mulligan B.

The mulligan concept of manual therapy.

Elsevier, Australia 2015; 1-489.Demoulin C, Depas Y, Vanderthommen M, Henrotin Y, Wolfs S, Cagnie B, Hidalgo B.

Orthopaedic manual therapy: Definition, characteristics

and update on the situation in Belgium.

Rev Med Liège 2017; 72: 126-31Niemisto L, Lahtinen-Suopanki T, Rissanen P, Lindgren KA, Sarna S, Hurri H.

A randomized trial of combined manipulation, stabilizing exercises,

and physician consultation compared to physician consultation

alone for chronic low back pain.

Spine 2003; 28: 2185-91Kent P, Mjosund HL, Petersen DH.

Does targeting manual therapy and/or exercise improve patient outcomes

in nonspecific low back pain? A systematic review.

BMC Med 2010; 8(22): 1-15Waddell G, Phillips RB.

The back pain revolution.

In: Churchill Livingstone Edinburgh 2000; 1-480.Puentedura EJ, Landers MR, Cleland JA, Mintken PE, Huijbregts P, Fernandez-de-Las-Penas C.

Thoracic spine thrust manipulation versus cervical spine thrust manipulation

in patients with acute neck pain: A randomized clinical trial.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2011; 41: 208-20Gonzalez-Iglesias J, Fernandez-de-las-Penas C, Cleland JA, Gutierrez-Vega R.

Thoracic spine manipulation for the management of patients with neck pain:

A randomized clinical trial.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2009; 39: 20-7Blikstad A, Gemmell H.

Immediate effect of activator trigger point therapy and myofascial

band therapy on non-specific neck pain in patients with upper

trapezius trigger points compared to sham ultrasound:

A randomised controlled trial.

Clinical Chiropractic 2008; 11: 23-29.Gemmell H, Miller P, Nordstrom H.

Immediate effect of ischaemic compression and trigger point pressure

release on neck pain and upper trapezius trigger points:

A randomised controlled trial.

Clinical Chiropractic 2008; 11: 30-36.Bronfort G, Evans R, Anderson AV, Svendsen KH, Bracha Y, Grimm RH.

Spinal Manipulation, Medication, or Home Exercise With Advice

for Acute and Subacute Neck Pain: A Randomized Trial

Annals of Internal Medicine 2012 (Jan 3); 156 (1 Pt 1): 1–10Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Street JH, Hunt M, Barlow W.

Pitfalls of patient education. Limited success of a pogam fo back pain in primary care.

Spine 1996; 21: 345-55Masaracchio M, Cleland JA, Hellman M, Hagins M.

Short-term combined effects of thoracic spine thrust manipulation

and cervical spine nonthrust manipulation in individuals with

mechanical neck pain: A randomized clinical trial.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2013; 43: 118-27Izquierdo Perez H, Alonso Perez JL, Gil Martinez A, La Touche R, et al.

Is one better than another? A randomized clinical trial

of manual therapy for patients with chronic neck pain.

Man Ther 2014; 19: 215-21Lopez-Lopez A, Alonso Perez JL, Gonzalez Gutierez JL, et al.

Mobilization versus manipulations versus sustain appophyseal natural

glide techniques and interaction with psychological factors for

patients with chronic neck pain: Randomized control Trial.

Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2015; 51: 121-32Saavedra-Hernandez M, Castro-Sanchez AM, Arroyo-Morales M, Cleland JA.

Short-term effects of kinesio taping versus cervical thrust manipulation

in patients with mechanical neck pain: A randomized clinical trial.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2012; 42: 724-30Martinez-Segura R, De-la-Lave-Rincon AI, Ortega-Santiago R.

Immediate changes in widespread pressure pain sensitivity, neck pain,

and cervical range of motion after cervical or thoracic thrust

manipulation in patients with bilateral chronic mechanical

neck pain: A randomized clinical trial.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2012; 42: 806-14Kanlayanaphotporn R, Chiradejnant A, Vachalathiti R.

The immediate effects of mobilization technique on pain and range

of motion in patients presenting with unilateral neck pain:

A randomized controlled trial.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009; 90: 187-92Schomacher J.

The effect of an analgesic mobilization technique when applied at

symptomatic or asymptomatic levels of the cervical spine in

subjects with neck pain: A randomized controlled trial.

J Man Manip Ther 2009; 17: 101-8Evans R, Bronfort G, Schulz C, et al.

Supervised Exercise With And Without Spinal Manipulation

Performs Similarly And Better Than Home Exercise For

Chronic Neck Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012 (May 15); 37 (11): 903–914Gross A, Miller J, D’Sylva J, Burnie S, Goldsmith G, Graham N et al..

Manipulation or Mobilisation For Neck Pain: A Cochrane Review

Manual Therapy 2010 (Aug); 15 (4): 315–333Hurwitz EL, Morgenstern H, Vassilaki M, Chiang LM.

Adverse reactions to chiropractic treatment and their effects on satisfaction

and clinical outcomes among patients enrolled in

the UCLA Neck Pain Study.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2004; 27: 16-25Carnes D, Mars TS, Mullinger B, Froud R, Underwood M.

Adverse events and manual therapy: A systematic review.

Man Ther 2010; 15: 355-63Cagnie B, Vinck E, Beernaert A, et al.

How Common Are Side Effects of Spinal Manipulation And

Can These Side Effects Be Predicted?

Manual Therapy 2004 (Aug); 9 (3): 151–156Paanalahti K, Holm LW, Nordin M, Asker M, Lyander J, Skillgate E.

Adverse events after manual therapy among patients seeking care

for neck and/or back pain: A randomized controlled trial.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014; 15: 77Thomas LC, Rivett DA, Attia JR, Levi CR.

Risk factors and clinical presentation of craniocervical arterial dissection:

A prospective study.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2012; 13: 164Kerry R, Taylor AJ, Mitchell J, McCarthy C, Brew J.

Manual therapy and cervical arterial dysfunction, directions for the future: A clinical perspective.

J Man Manip Ther 2008; 16: 39-48Cassidy JD, Bronfort G, Hartvigsen J.

Should we abandon cervical spine manipulation for mechanical neck pain? No.

BMJ 2012; 344: 3680Wand BM, Heine PJ, O’Connell NE.

Should we abandon cervical spine manipulation for mechanical neck pain? Yes.

BMJ 2012; 344: 3679Haldeman S, Kohlbeck FJ, McGregor M.

Stroke, Cerebral Artery Dissection, and Cervical Spine Manipulation Therapy

J Neurology 2002 (Jul); 249 (8): 1098–1104Thomas LC.

Cervical arterial dissection: An overview and implications

for manipulative therapy practice.

Man Ther 2016. Feb; 21: 2-9Ford JJ, Hahne AJ.

Complexity in the physiotherapy management of low back disorders:

Clinical and research implications.

Man Ther 2013; 18: 438-42Foster NE, Hill JC, O’Sullivan P, Hancock M.

Stratified models of care.

Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2013; 27: 649-61Dewitte V, Beernaert A, Vanthillo B, Barbe T, Danneels L, Cagnie B.

Articular dysfunction patterns in patients with mechanical neck pain:

A clinical algorithm to guide specific mobilization

and manipulation techniques.

Man Ther 2014; 19: 2-9Jones M, Edwards I, Gifford L.

Conceptual models for implementing biopsychosocial theory in clinical practice.

Man Ther 2002; 7: 2-9Hidalgo B.

Evidence based orthopaedic manual therapy for patients

with non-secific low back pain: An integrative approach.

J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2016; 29: 231-9Llamas-Ramos R, Pecos-Martin D, Gallego-Izquierdo T, Llamas-Ramos I, et al.

Comparison of the short-term outcomes between trigger point dry needling

and trigger point manual therapy for the management of chronic

mechanical neck pain: a randomized clinical trial.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2014; 44: 852-61Madson TJ., Cieslak KR., Gay RE.,

Joint mobilization vs massage for chronic mechanical neck pain:

a pilot study to assess recruitment strategies

and estimate outcome measure variability,

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2010; 33: 644-51Salom-Moreno J, Ortega-Santiago R, Cleland JA, Palacios-Cena M.

Immediate changes in neck pain intensity and widespread pressure pain sensitivity

in patients with bilateral chronic mechanical neck pain: a randomized

controlled trial of thoracic thrust manipulation

vs non-thrust mobilization.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2014; 37: 312-9Leaver AM., Maher CG., Herbert RD., Latimer J., McAuley JH., Jull G., et al.

A randomized controlled trial comparing manipulation

with mobilization for recent onset neck pain,

Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010; 91: 1313-8Saavedra-Hernandez M., Arroyo-Morales M., Cantarero-Villanueva I., et al.

Short-term effects of spinal thrust joint manipulation in

patients with chronic neck pain: a randomized clinical trial,

Clin Rehabil 2013; 27: 504-12Cleland JA, Glynn P, Whitman JM, Eberhart SL, MacDonald C, Childs JD.

Short-term effects of thrust versus nonthrust mobilization/manipulation

directed at the thoracic spine in patients with neck pain: a randomized clinical trial.

Phys Ther 2007; 87: 431-40Suvarnnato T., Puntumetakul R., Kaber D., Boucaut R., Boonphakob Y., et al.

The effects of thoracic manipulation versus mobilization for

chronic neck pain: a randomized controlled trial pilot study,

J Phys Ther Sci 2013; 25: 865-71Dziedzic K., Hill J., Lewis M., Sim J., Daniels J., Hay EM.,

Effectiveness of manual therapy or pulsed shortwave diathermy in addition

to advice and exercise for neck disorders: a pragmatic randomized

controlled trial in physical therapy clinics,

Arthritis Rheum 2005; 53: 214-22Saayman L., Hay C., Abrahamse H.,

Chiropractic manipulative therapy and low-level laser therapy in the management

of cervical facet dysfunction: a randomized controlled study,

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2011; 34: 153-63Zaproudina N., Hanninen OO., Airaksinen O.,

Effectiveness of traditional bone setting in chronic neck pain:

randomized clinical trial,

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2007; 30: 432-7Snodgrass SJ., Rivett DA., Sterling M., Vicenzino B.,

Dose optimization for spinal treatment effectiveness: a randomized

controlled trial investigating the effects of high and low

mobilization forces in patients with neck pain,

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2014; 44: 141-52Ylinen J., Kautiainen H., Wiren K., Hakkinen A.,

Stretching exercises vs manual therapy in treatment of

chronic neck pain: a randomized, controlled cross-over trial.

J Rehabil Med 2007; 39: 126-32Lluch E., Schomacher J., Gizzi L., Petzke F., Seegar D., Falla D.,

Immediate effects of active cranio-cervical flexion exercise versus

passive mobilisation of the upper cervical spine on pain

and performance on the cranio-cervical flexion test,

Man Ther 2014; 19: 25-31Martinez-Segura R, Fernandez-de-las-Penas C, Ruiz-Saez M.

Immediate Effects on Neck Pain and Active Range of Motion After a Single

Cervical High-velocity Low-amplitude Manipulation in Subjects Presenting

with Mechanical Neck Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2006 (Sep); 29 (7): 511–517Vernon H., Triano JT., Soave D., Dinulos M., Ross K., Tran S.,

Retention of blinding at follow-up in a randomized clinical study

using a sham-control cervical manipulation procedure for neck pain:

secondary analyses from a randomized clinical study,

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2013; 36: 522-6Hoving JL, Koes BW, de Vet HC, van der Windt DA, Assendelft WJ, van Mameren H, et al.

Manual Therapy, Physical Therapy, or Continued Care by a General Practitioner

for Patients with Neck Pain. A Randomized, Controlled Trial

Annals of Internal Medicine 2002 (May 21); 136 (10): 713–722Dunning JR, Cleland JA, Waldrop MA, Arnot CF, Young IA, Turner M, et al.

Upper cervical and upper thoracic thrust manipulation versus nonthrust

mobilization in patients with mechanical neck pain:

a multicenter randomized clinical trial.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2012; 42: 5-18Palmgren PJ, Sandstrom PJ, Lundqvist FJ, Heikkila H.

Improvement After Chiropractic Care in Cervicocephalic Kinesthetic

Sensibility and Subjective Pain Intensity in Patients

with Nontraumatic Chronic Neck Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2006 (Feb); 29 (2): 100–106Martel J, Dugas C, Dubois JD, Descarreaux M.

A Randomised Controlled Trial of Preventive Spinal Manipulation With

and Without a Home Exercise Program for Patients

With Chronic Neck Pain

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011 (Feb 8); 12: 41Cleland JA, Childs JD, McRae M, Palmer JA, Stowell T.

Immediate effects of thoracic manipulation in patients

with neck pain: a randomized clinical trial.

Man Ther 2005; 10: 127-35Escortell-Mayor E., Riesgo-Fuertes R., Garrido-Elustondo S., et al.

Primary care randomized clinical trial: manual therapy effectiveness

in comparison with TENS in patients with neck pain,

Man Ther 2011; 16: 66-73McReynolds TM., Sheridan BJ.,

Intramuscular ketorolac versus osteopathic manipulative treatment

in the management of acute neck pain in the emergency department:

a randomized clinical trial,

J Am Osteopath Assoc 2005; 105: 57-68Boyles RE., Walker MJ., Young BA., Strunce J., Wainner RS.,

The addition of cervical thrust manipulations to a manual physical

therapy approach in patients treated for mechanical neck pain: a secondary analysis,

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2010; 40: 133-40Evans R., Bronfort G., Bittell S., Anderson AV.,

A pilot study for a randomized clinical trial assessing chiropractic care,

medical care, and self-care education for acute and subacute neck pain patients.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2003; 26: 403-11Groeneweg R, Kropman H, Leopold H, van Assen L, Mulder J. van Tulder MW, et al.

The effectiveness and cost-evaluation of manual therapy and physical therapy

in patients with sub-acute and chronic non specific neck pain.

Rationale and design of a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT).

BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010; 11: 14Hurwitz EL, Morgenstern H, Harber P, Kominski GF, Yu F, Adams AH.

A Randomized Trial of Chiropractic Manipulation and Mobilization

for Patients With Neck Pain: Clinical Outcomes From

the UCLA Neck-Pain Study

Am J Public Health 2002 (Oct); 92 (10): 1634–1641Kanlayanaphotporn R., Chiradejnant A., Vachalathiti R.,

Immediate effects of the central posteroanterior mobilization technique

on pain and range of motion in patients with mechanical neck pain,

Disabil Rehabil 2010; 32: 622-8Hoving JL, Koes BW, de Vet HC, van der Windt DA, Assendelft WJ, van Mameren H, et al.

Manual Therapy, Physical Therapy, or Continued Care by a General Practitioner

for Patients with Neck Pain. A Randomized, Controlled Trial

Annals of Internal Medicine 2002 (May 21); 136 (10): 713–722Mansilla-Ferragut P., Fernandez-de-Las Penas C, Alburquerque-Sendin F, Cleland JA, Bosca-Gandia JJ.

Immediate effects of atlanto-occipital joint manipulation on active

mouth opening and pressure pain sensitivity in women

with mechanical neck pain.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2009; 32: 101-6Wood TG, Colloca CJ, Mathews R.

A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial on the Relative Effect of Instrumental

(MFMA) Versus Manual (HVLA) Manipulation in the Treatment

of Cervical Spine Dysfunction

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2001 (May); 24 (4): 260–271Strunk RG., Hondras MA.,

A feasibility study assessing manual therapies to different regions

of the spine for patients with subacute or chronic neck pain,

J Chiropr Med 2008; 7: 1-8van Schalkwyk R., Parkin-Smith GF.,

A clinical trial investigating the possible effect of the supine cervical

rotatory manipulation and the supine lateral break manipulation

in the treatment of mechanical neck pain: a pilot study,

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2000; 23: 324-31Walker MJ., Boyles RE., Young BA., Strunce JB., Garber MB., Whitman JM., et al.

The effectiveness of manual physical therapy and exercise

for mechanical neck pain: a randomized clinical trial,

Spine 2008; 33: 2371-8Hanten WP., Olson SL., Butts NL., Nowicki AL.,

Effectiveness of a home program of ischemic pressure followed by

sustained stretch for treatment of myofascial trigger points

Phys Ther 2000; 80: 997-1003Hakkinen A., Salo P., Tarvainen U., Wiren K., Ylinen J.,

Effect of manual therapy and stretching on neck muscle

strength and mobility in chronic neck pain,

J Rehabil Med 2007; 39: 575-9Ali A., Shakil-ur-Rehman S., Sibtain F.,

The efficacy of sustained natural apophyseal glides with and without

isometric exercise training in non-specific neck pain

Pak J Med Sci 2014; 30: 872-4Beltran-Alacreu H., Lopez-de-Uralde-Villanueva I, Fernandez-Carnero J, La Touche R.

Manual therapy, therapeutic patient education, and therapeutic exercise,

an effective multimodal treatment of nonspecific chronic neck pain.

Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2015; 10: 887-97.

Return to CHRONIC NECK PAIN

Since 11-02-2022

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |