|

Today’s Chiropractic; Vol 27, No 5: 3247

Autism, Asthma, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Strabismus, and Illness Susceptibility: A

Case Study in Chiropractic Management

William C. Amalu, DC, DABCT, DIACT, FIACT

ABSTRACT:

Pathologies of organic

origin are commonly thought to be the exclusive realm of medical treatment and not part of

the mainstay of chiropractic care. The clinical observations of a patient presenting with

autism, asthma, irritable bowel syndrome, strabismus, and illness susceptibility are

reported. Alleviation of symptoms is seen subsequent to corrections of abnormal

biomechanical function of the occipito-atlanto-axial complex. A relationship between

biomechanical faults in the upper cervical spine and the manifestation of abnormal central

neurophysiological processing is suggested as the genesis of this patient’s

symptomatology.

Key words: Autism, Asthma, IBS, Strabismus, Infrared Imaging, Upper Cervical Spine.

INTRODUCTION

Autism

usually manifests itself in the first year of life with onset rarely later than 30 months

of age. The cause of autism is unknown, but evidence points to a neurological basis. The

syndrome is characterized by extreme aloneness (lack of attachment, failure to cuddle, and

avoidance of eye contact); insistence on sameness (resistance to change, ritual morbid

attachment to familiar objects, and repetitive acts); disordered speech and language

(which varies from total muteness to markedly idiosyncratic use of language); and uneven

intellectual performance. The syndrome tends to maintain a consistent symptomatic picture

throughout development.

Medical treatment, for the

most severely impaired children, includes systematic application of behavior therapy; a

technique that can be taught to parents in order to help manage the child in the home and

at school. The benefits of this therapy vary widely, but may be considerable for these

children who try the patience of the most loving parents and devoted teachers. Medications

provide limited benefit and are used mainly in controlling the most severe forms of

aggressive and self-destructive behavior. However, they do not resolve the condition. [13]

Asthma is a lung disease

characterized by: airway obstruction that is reversible (but not completely in some

patients), airway inflammation, and increased airway responsiveness to a variety of

stimuli. The airway obstruction in asthma is due to a combination of factors that include:

smooth muscle spasm of the airways, edema of the airway mucosa, increased mucus secretion,

cellular infiltration of the airway walls, and injury and desquamation of the airway

epithelium. A family history of allergy or asthma can be elicited in most asthmatics.

Research on the

pathophysiology of asthma over the past decade has focused on the inflammatory cells and

their mediators, neurogenic mechanisms, and vascular abnormalities involved. Recent

interest in neurogenic mechanisms has focused on neuropeptides released from sensory

nerves by an axon reflex pathway. These peptides have vascular permeability and mucus

secretagogue activity, bronchoconstrictor activity, and a bronchial vascular dilation

effect. These sensory nerves also act on the pulmonary airways and their microvasculature

contributing to the special kind of airway inflammation that is characteristic of asthma.

The medical treatment of

asthma may be conveniently considered as management of the acute attack and day-to-day

therapy. Drug therapy focuses on the two main aspects of the disease: bronchospasm and

inflammation. Sympathomimetic medications cause bronchial smooth muscle relaxation as

their effects mimic those of the sympathetic nervous system. The inflammatory aspect is

managed with corticosteroids. While systemic corticosteroids are considered exceptionally

effective, they are reserved for more difficult episodes because of their potential for

serious adverse effects. [13]

Irritable bowel syndrome

(IBS) is characterized as a motility disorder involving the entire hollow GI tract,

creating an upper and lower GI symptom complex. The etiology of IBS is unknown. No

anatomic cause can be found. Two major groups or clinical types of IBS are recognized. In

the spastic colon type, most patients have pain over one or more areas of the colon

associated with periodic constipation or diarrhea. The second group of IBS patients

primarily manifest painless diarrhea, usually urgent, precipitous diarrhea that occurs

immediately upon rising or, more typically, during or immediately after a meal.

The pathophysiology of

IBS is based upon motor abnormalities of both the small and large bowel. When the normal

segmentation mechanism of the sigmoid colon becomes hyperreactive, so-called spastic

constipation results. In contrast, diminished motor function is found in the group

associated with diarrheal episodes. Treatment is basically supportive and palliative. If

offending foods can be identified, diet changes are suggested. Medical management with

drugs are used only as a temporary expedient to relieve spastic pain. [13]

Strabismus is

characterized as the deviation of one eye from parallelism with the other. The etiology is

either paralytic or myospasmotic. Paralytic (nonconcomitant) strabismus results from

paralysis of one or more ocular muscles and may be caused by a specific oculomotor nerve

lesion. Nonparalytic (concomitant) strabismus usually results from unequal ocular muscle

tone caused by a supranuclear abnormality within the CNS. A concomitant strabismus may be

convergent (esotropia), divergent (exotropia), or vertical (hyper- or hypotropia).

The focus of medical

treatment is for muscle imbalance. If this alone is responsible, strabismus is treated

early with corrective glasses or contact lenses, medications, orthoptic training (eg. eye

exercises, patching the normal eye, etc.), or surgical restoration of the muscle balance.

Permanent loss of vision can occur if strabismus and its attendant amblyopia are not

treated before the age of 4 to 6 yrs., with intermittent follow-up examinations at least

until age 10. [13]

Considering the above

pathophysiology and treatment approach to this patient’s conditions, it can be

understood that the contribution of chiropractic care in the management of these diseases

is considered to be of no significance to the medical community. However, the body of

literature detailing a possible upper cervical etiology, or at least contribution, is

substantial; and the case made for greater recognition of the involvement of abnormal

upper cervical spine biomechanics is compelling.

CASE REPORT

A 5 year old female was

referred to our clinic with the chief complaint of autism. Her parents advised that the

patient had also been diagnosed with asthma, allergies, irritable bowel syndrome, and left

sided strabismus. The patient’s diagnosis was made through an extensive medical

workup at a specialized autism research institute with the other conditions diagnosed over

time by various medical specialists.

Her mother reported that

she had been very susceptible to illnesses since birth, but had experienced normal

development until a viral upper respiratory illness at 21 months of age. The URI developed

into a complication with asthma necessitating a 5 day regimen of prednisone. The

patient’s mother advised that she was never the same and began to deteriorate from

that point on.

At the time of

consultation, the patient had been experiencing 25 violent temper episodes per day with

each episode lasting up to 20 minutes. The episodes consisted of ear piercing screams,

combatant behavior, and the patient throwing herself onto the floor. She also exhibited 3

episodes each day of self-inflicted violent behavior which included biting her arm,

slapping her head, and repeatedly banging her head against a full length mirror. Her

parents advised that she also expressed at least 1 episode each day of outward violent

behavior which consisted of hitting people, especially her mother to include slapping the

glasses off her face.

The patient’s speech

was limited to only a few words such as mama, dada, milk, and walk. Her fine motor skills

were delayed to the extent that she could only feed herself with her fingers. The

patient’s sleep pattern was considerably disturbed with waking screaming at least

twice at night and once with napping. It was also very difficult to get her back to sleep

once this occurred. The most difficult time was trying to get the patient to sleep in the

evening. Every night consisted of 11 1/2 hours of screaming, comforting, and stories just

to get her to sleep.

The irritable bowel

syndrome was described by her parents as profuse loose bowel movements which would occur 4

times a day with the need to change clothes. They were unable to correlate any food

sensitivities or pattern to the bowel movements. Due to her overall condition she was

unable to be toilet trained. Her parents also noted that she was allergic to dust and

plastics. She had constant eczema behind each ear along with rashes, redness, and sores

which could appear at random anywhere on her body.

Her parents noted that

she had continued to be very susceptible to illnesses. Out of 810 months per year, the

patient would experience a URI or flu lasting at least 3 weeks each time. Of these

illnesses, 50% would include asthma attacks necessitating the use of albuteral or a 5 day

regimen of prednisone. Occasionally, she would have to be taken for in-office nebulizer

treatment.

At the time the patient

was seen in our clinic, she had been undergoing various forms of home behavior therapies

along with attempted eye patching with limited results. Her parent’s noted that most

of her symptoms were getting worse in both intensity and frequency.

Upon examination, the

patient presented in constant motion with running on her toes while loosely flapping her

hands and arms. Her gait included a bilateral toe-in with a marked increase on the right.

She was uncommunicative, uncooperative, and prone to screaming violent outbursts. Vital

signs, ear, nose, and throat examinations were unremarkable with the exception of

bilateral posterior auricular eczema.

Orthopedic examination

revealed significant palpatory hypertonicity of the paraspinal musculature from the

occiput to C3 bilaterally with a marked increase on the right. A combination of screaming,

arched cervical extension, and outward violence suggested tenderness in the same areas.

The patient demonstrated a reduction in passive cervical extension and right lateral

flexion. Her lumbosacral evaluation was unremarkable.

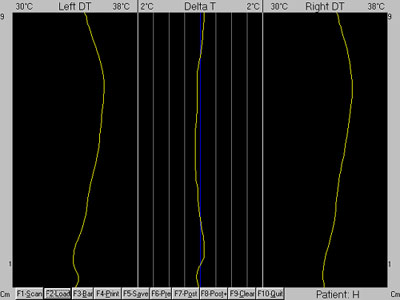

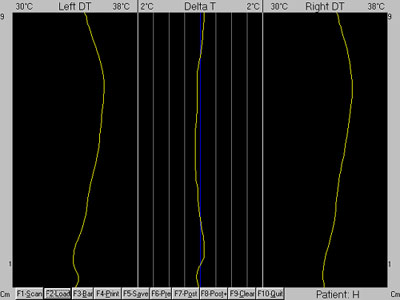

Figure 1 |

Gross

neurologic examination was also found to be unremarkable. A moderate left

esotropia was noted along with a mild right. A paraspinal digital infrared

imaging analysis was performed in accordance with thermographic protocol. [46] Due to the patient’s violent behavior, she had to be restrained

by both parents and the doctor in order to take the scan. A continuous paraspinal

scan consisting of approximately 300 infrared samples was taken from the

level of S1 to the occiput (Fig. 1).

|

The data was analyzed against established normal values and found to contain

wide thermal asymmetries indicating abnormal autonomic regulation or neuropathophysiology [710] (Figs. 2 and 3).

Figure 2

|

Figure 3

|

Since the cervical spine displayed highly abnormal thermal asymmetries, a

focused scan was performed with approximately 75 infrared samples taken from T1 to the

occiput (Figs. 4 and 5).

Figure

4 |

Figure 5

|

The full

spine scans also displayed an abnormal central hypothermia of the spine, which suggests

long standing nervous system dysfunction (Figs. 2 and 6).

Figure

2 |

Figure 6

|

The above information yielded a high suspicion of abnormal upper cervical arthrokinematics.

Consequently, a precision upper cervical radiographic series was performed for

an accurate analysis of specific segmental biomechanics. [11] Since positioning

chairs and head clamps cannot be used with infants or uncooperative children,

supine table films were taken using an on-patient laser-optic alignment system

to precisely align the patient to the central ray. With this system, maintenance

of precision patient alignment can be facilitated without a head clamp system

due to the laser being aligned to the source of the X-ray beam rather than the

bucky. However, with children who are old enough to sit on their own, weight-bearing

laser-optic alignment is preferred (Figs. 7 and 8).

Figure

7 |

Figure 8 |

An analytical radiographic

method consisting of mensuration combined with arthrokinematics was performed. [11]

Biomechanical abnormalities were noted at the atlanto-occipital and atlanto-axial

articulations.

CHIROPRACTIC MANAGEMENT

Correction of the

atlanto-occipital subluxation was chosen as the first to be adjusted from the accumulated

degree of aberrant biomechanics noted at this level. Before treatment was rendered, the

parents were counseled that they may expect exacerbations in symptomatology as part of the

normal response to care due to the global impact of neural reintegration.

To correct the

subluxation, the patient was placed on a specially designed knee-chest table with the

posterior arch of atlas as the contact point. An adjusting force was introduced using a

specialized upper cervical adjusting procedure. [12] The patient was then placed in a

post-adjustment recuperation suite for 15 minutes as per thermographic protocol. [46]

Correction of the subluxation was determined from the post-adjustment cervical infrared

scan noting resolution of the patient’s presenting neuropathophysiology (Figs. 9 and

10).

Figure 9 |

Figure 10

|

All subsequent office visits included an

initial cervical infrared scan; and if care was rendered, another scan was performed to

determine if normal neurophysiology was restored. Since the focus of the patient’s

care was in the upper cervical spine, infrared scans were made in this region only during

normal treatment visits with full spine scans performed at 30day re-evaluation intervals.

The patient was adjusted

twice during the first week of care. After the first adjustment, the patient’s mother

noted that she had her first good night sleep since she could remember. By the end of the

week, she reported that the patient’s violent temper episodes had reduced to 15 per

day along with a substantial decreased in intensity. She noted that reasoning with the

patient could stop them now. The patient’s self-inflicted violent behavior was also

decreasing in frequency. Her speech had suddenly improved with an increase in vocabulary

with the ability to expressing feelings (saying hungry, tired, mad). Her sleep pattern

also changed to waking only once at night along with longer napping times. The

patient’s mother reported that she was running less and walking more flat footed.

Performing thermal scans had also become much easier as she was now able to sit on her own

without restraint.

During the second week of

care the patient was adjusted only once. Her mother reported that by the end of the week

the temper episodes had decreased to only 5 per day with a further decrease in intensity.

She also noted that she was able to stop them quickly. The patient’s left strabismus

had improved to the point that her mother noticed it only twice since the week before. She

advised that the right eye showed no signs of strabismus since treatment began. The

patient’s mother was elated to report that she had been increasingly vocal this week

and began speaking in sentences for the first time. She was also able to nap now without

waking and woke only once per night this week with the ability to go back to sleep on her

own. Her toe in gait continued to decrease with more flat-footed walking. Her mother

reported a marked decrease in hyperactivity along with wanting to be touched and hugged

now.

The patient was adjusted

once during the third week of care. By the end of the week, the patient’s violent

temper episodes had decreased to only twice per day with a continued decrease in

intensity. Her mother noted that she continued to speak using more sentences and

vocalizing disappointment, anger, hunger, tiredness, and other feelings. The

patient’s strabismus was now showing up in the left eye only when tired. Her gait was

absent of toe-in by this time. Her mother advised that there was very little running or

hyperactivity now. She had also ceased to display any self or outward violent behavior.

The patient’s mother also noted that her IBS had improved to the point of 12 loose

bowel movements per day with only an occasional need to change clothes. She noted that the

patient was now beginning to recognize bowel and bladder functions on her own. Because she

was doing so well, they decided to go to a friend’s house as a family for the first

time. The patient’s social behavior was excellent; she played with their dog, used

the stairs without falling, and came home and asked to go to bed because she was tired.

No adjustments were

necessary during the fourth week of care. The patient’s mother reported that by the

end of this week all temper episodes, hyperactivity, self and outward violent behavior had

stopped. She was now napping and sleeping through the night perfectly. The patient was

also walking more and more, running less, and showed no signs of toe-in. Her mother

advised that there were no signs of any strabismus by this time. The IBS continued to

improve with only one loose bowel movement per day at the most and only a rare clothing

change. Her mother also noted that the eczema behind her ears had cleared up and that her

allergic skin reactions had stopped.

Before entering our clinic

for care, an appointment had been made at a special autism, occupational therapy, and

speech center to evaluate the patient for specialized therapy. Her parents decided to keep

the appointment due to the difficulty in getting one in the first place and to see what if

anything could further the patient’s development. The patient underwent one hour of

observation and evaluation by two therapists. Upon conferring their findings they both

reported that the patient did not have autism and that there must have been a

misdiagnosis. The patient’s mother was pleasantly amused and elated by this and

proceeded to explain in detail the patient’s behavior four weeks previously. Upon

hearing this, the therapists agreed that the original diagnosis was autism, but that the

patient was not currently exhibiting this disorder. They reported that due to her current

level of behavior that she would not need in-center therapy and that they would give the

parents work for her to do at home. Their report also noted that at her current rate of

improvement she would be able to function in society.

A re-evaluation was also

performed in our center at this time. The examination revealed: no signs of posterior

auricular eczema, normal cervical muscle tone, cervical PROMs WNL, lack of toe-in gait,

and bilateral central positioning of the eyes. A full spine paraspinal infrared scan was

performed at this time noting near total resolution of the patient’s presenting

neuropathophysiology along with a return of normal central spinal heat (Figs. 11, 12, and

13).

Figure

11 |

Figure 12

|

Figure 13

Having the patient in the

office had become a pleasure by now. She would hold my hand while walking down the hall,

position herself with her back to the examining chair while allowing me to lift her up to

sit, and finally holding her own hair out of the way for me to perform an infrared scan.

Weeks six and eight were

punctuated by a mild return of symptoms. The patient’s mother advised that the temper

episodes had returned at approximately once per day along with her left strabismus, but

that both were very mild in intensity. Concomitantly, her infrared scans noted a return of

her presenting neuropathophysiology necessitating an adjustment once during each week. All

of her other conditions continued to improve at a steady rate. Her mother reported that

she was climbing, exploring, and doing things she would never do before. A re-examination

was performed at eight weeks with no remarkable findings.

Figure 14 |

No

adjustments were needed during the ninth through twelfth weeks of care.

The patient’s mother continued to report improvements with no temper

episodes, self or outward violent behavior, or strabismus (Fig. 14). Her

sleeping habits remained undisturbed. The patient’s hyperactivity continued

to decrease along with an increased frequency of a heel-toe gait. Her speech

continued to improve with more and more sentence use. The IBS had almost

completely resolved with no episodes needing a change of clothes. |

The patient continued to

improve over the next 8 months. Adjustments were rendered very infrequently. Her mother

reports that the patient currently exhibits the type of anger in intensity and frequency

that normal children have when not getting their way, etc. The patient may rarely show

some self-violent behavior with slapping her own head if she is over stimulated or very

tired. Any outward violent behavior, if ever seen, is described by her mother as usual

childhood behavior as when mad with a sibling. Her sleep pattern continues to be

undisturbed. She continues to improve in her speech development with increased use of

complex structured sentences. Her gross motor skills have improved to the point of

performing somersaults and playing catch, while her fine motor skills include work with

holding pencils correctly, using keys, and the ability to feed herself (even soup) using

utensils.

Her IBS has almost

completely resolved with possibly one loose bowel movement a week with no clothing

changes. To her mother’s delight she is now toilet training. Her left strabismus is a

rare occurrence, hardly noticeable, and only when she is extremely tired. The

patient’s mother reports that her allergies and eczema never returned. She has also

never had another asthma attack. Over the past eleven months of care, the patient has

experienced only three minor colds lasting at the most five days. Considering the amount

of developmental delay, learning disabilities, and immune dysfunction seen in this

patient, it is amazing how much progress she made in such a short amount of time. However,

even though improvements continue day-by-day, she still has a long way to go.

NEUROBIOLOGICAL MECHANISMS

There are two extensively

studied neurophysiological mechanisms which may explain the profound changes seen in this

patient. The first is CNS facilitation. [1317] This condition arises from an initiating

trauma (birth, falling, etc.) which causes entrapment of intra-articular meniscoids

resulting in segmental hypomobility and finally compensatory hypermobility. Consequently,

hyperexcitation of intra and periarticular mechanoreceptors and nociceptors occurs. Over

time, this bombardment of the central nervous system can cause facilitation. Facilitation

results in an exponential rise in afferent signals to the cord and/or brain. This may

cause a loss of central neural integration due to direct excitation, or a lack of normal

inhibition, of pathways or nuclei at the level of the cord, brainstem, and/or higher brain

centers. The upper cervical spine is uniquely suited to this condition as it possesses

inherently poor biomechanical stability along with the greatest concentration of spinal

mechanoreceptors.

The second mechanism is

cerebral penumbra or brain cell hibernation. [1824] Previous research held that the

neuron had two basic states of existence: function and dysfunction. However, a third state

was uncovered which may explain the rapid and profound changes seen in some cases. When a

certain threshold of ischemia is reached, the neuronal state of hibernation occurs; the

cell remains alive, but ceases to perform its designated purpose. Entire functional areas

of the cerebral cortex or cerebellum may be affected. The mechanism of hyperafferancy, as

mentioned above, plays an initiating role. Hyperafferant activation of the central

regulating center for sympathetic function in the brain may cause differing levels of

cerebral ischemia. A second route via the superior cervical sympathetic ganglia, may also

cause higher center ischemia.

These recent advances in

neurophysiological research correlate well with the pathophysiology currently proposed in

the presented conditions. [13] Normalization of frontal lobe and limbic system

physiology would account for this patient’s drastic personality and behavior changes. [13]

Cerebral penumbra may hold the greatest explanation for the changes seen in autism

with specialized upper cervical chiropractic care.

Since recent research has

elucidated neurogenic mechanisms which cause bronchoconstriction, mucus secretion, and

airway inflammation in asthmatics [13]

, normalization of neural function could correct

the condition. In the treatment of asthma, sympathomimetic drugs are used to mimic the

normal activity of the sympathetic system. [13]

Why not return function to this system

rather than prescribing drugs that mimic it. Normalization of pathological central

sympathetic regulation due to cerebral penumbra, and/or direct pathophysiological spinal

pathway integration to the bronchial tree, may explain our effects.

In the case of strabismus,

supranuclear abnormalities within the CNS or direct occulomotor nerve dysfunction can

cause unequal ocular muscle tone. [13]

Correction of cerebral penumbra and/or facilitated

pathways could explain the return of normal central ocular positioning in this patient.

Motor nerve abnormalities

which cause the bowel motility dysfunction seen in irritable bowel syndrome [13]

, may

arise from either pathologies of central motor regulation due to cerebral penumbra or loss

of direct pathway controls. Normalization of motor nerve function would cause a return of

regular bowel motility.

The role that the

sympathetic nervous system plays in the regulation of immune function is substantial. [13]

Dysregulation of this system can result in sympathetically mediated immune

dysfunction and thus, susceptibility to illnesses. Correction of pathological central

sympathetic regulation resulting from cerebral penumbra and/or facilitation would lead to

a return of normal immune function.

CONCLUSION

The most important factor

in this case was our ability to objectively monitor the adjustment’s affects on the

patient’s neurophysiology. Many different types of tests are used in our profession

such as leg length, cervical challenge, motion and static palpation, and others. However,

these tests lack objectivity, posses inherent errors, and have no literature confirmation

of their ability to monitor neurophysiology. [2528] Digital infrared imaging, however,

has been researched for over 30 years compiling almost 9,000 peer-reviewed and indexed

articles confirming its use as an objective measure of neurophysiology. By using this

technology, our clinic has been able to consistently determine the correct adjustive

procedures that produce reproducible and dramatic positive neurophysiological improvements

in our patients.

If the foundation of our

profession stands on the principle that homeostasis is dependent upon coordinated

neurophysiology, then we must directly and objectively monitor this system as an outcome

measure to our care. But not any way of monitoring this system will suffice. We need to

measure the autonomic nervous system if we are to monitor the global systemic aspect of

the nervous system’s control. Paraspinal digital infrared imaging fulfills this need

by objectively measuring the autonomic changes of all 32 spinal nerves as they exit to

effect deep visceral function. Since testing does not involve patient compliance, such as

movement or a verbal response, paraspinal infrared imaging becomes as objective a test of

neurophysiology as we can get.

To what magnitude the

upper cervical spine is involved in the genesis of organic conditions remains to be seen.

In an atmosphere where much of the public see our profession as useful for neck and back

pain treatment at most, patients with complex disorders are left unaware of the possible

benefits of care. The body of literature detailing a possible upper cervical etiology, or

at least contribution, to organic disorders is substantial. Further research into this

area of the spine, combined with objective monitoring of neurophysiology, may reveal that

chiropractic does indeed offer consistent conservative management of complex visceral

disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

The

authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the Titronics Corporation.

For without their design of the TyTron C-3000 Paraspinal Digital Infrared

Scanner, we would not have been able to monitor this patient’s neurophysiology.

REFERENCES:

1.) Schroeder, S., Krupp, M., Tierney, L.

Current

Medical Diagnosis and Treatment.

Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lang; 1988.

2.) Berkow, R., Beers, M., et al.

Manual of Diagnosis

and Therapy.

Merk & Co.; 16th ed. 1992.

3.) Andreoli, T., Carpenter, C., Plum, F.

Essentials

of Medicine. 2nd ed.

Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1990.

4.) Thermography Protocols -

International Thermographic Society

1997.

5.) Thermography Protocols -

American Academy of Thermology 1984.

6.) Thermography Protocols -

American Academy of Medical Infrared Imaging 1997.

7.) Uematsu, S., Edwin, D., et al.

Quantification of Thermal Asymmetry. Part 1:

Normal Values and Reproducibility.

J Neurosurg 1988;69:552-555.

8.) Feldman, F., Nickoloff, E.

Normal Thermographic Standards in the Cervical Spine and Upper Extremities.

Skeletal Radiol 1984;12:235-249.

9.) Clark RP.

Human Skin Temperature and its Relevance

in Physiology and Clinical Assessment.

In: Francis E, Ring J, Phillips B, et al,

Recent Advances in Medical Thermology,

New York: Plenum Press, 1984:5-15.

10.) Uematsu S.

Symmetry of Skin Temperature Comparing One Side of

the Body to the Other.

Thermology 1985;1:4-7.

11.) Amalu, W., Tiscareno, L., et al.

Precision

Radiology: Module 1 and 5 -- Applied Upper Cervical Biomechanics Course.

International Upper Cervical Chiropractic Association, 1993.

12.) Amalu, W., Tiscareno, L., et al.

Precision Multivector Adjusting: Module 3 and 7 --

Applied Upper Cervical Biomechanics Course.

International Upper Cervical Chiropractic Association, 1993.

13.) Gardner, E.

Pathways to the Cerebral Cortex for Nerve Impulses from Joints.

Acta Anat 1969;56:203-216.

14.) Wyke, B.

The Neurology of Joints: A Review of General Principles.

Clin Rheum Dis 1981;7:223-239.

15.) Coote, J.

Somatic Sources of Afferent Input as Factors

in Aberrant Autonomic, Sensory, and Motor Function.

In: Korr, I., ed. The Neurobiologic Mechanisms in Manipulative Therapy.

New York: Plenum, 1978:91-127.

16.) Denslow, J., Korr, I., Krems, A.

Quantitative Studies of Chronic Facilitation in Human Motorneuron Pools.

Am J Physiol 1987;150:229-238

17.) Korr, I.

Proprioceptors and the Behavior of Lesioned Segments.

In: Stark, E. ed. Osteopathic Medicine.

Acton, Mass.: Publication Sciences Group, 1975:183-199.

18.) Heiss, W., Hayakawa, T., Waltz, A.,

Cortical Neuronal Function During Ischeamia.

Arch Neurol 1976;33:813-20

19.) Astrup, J., Siesjo, B., Symon, L.

Thresholds in Cerebral Ischemia -- The Ischemic Penumbra.

Stroke 1981;12:723-5

20.) Roski, R., Spetzler, R., Owen, M., et al.

Reversal of Seven Year Old Visual Field Defect

with Extracranial-Intracranial Anastomosis.

Surg Neurol 1978;10:267-8

21.) Mathew, R., Meyer, J., et al.

Cerebral Blood Flow in Depression.

Lancet 1980;1(818):1308

22.) Mathew, R., Weinmann, M., Barr, D.

Personality and Regional Cerebral Blood Flow.

Br J Psychiatry 1984;144:529-32

23.) Jacques, S. Garner, J.

Reversal of Aphasia with Superficial Temporal Artery

to Middle Cerebral Artery Anastomosis.

Surg Neurol

1976;5:143-5

24.) Lee, M., Ausman, J., et al.

Superficial Temporal to Middle Cerebral Artery Anastomosis.

Clinical Outcome in Patients with Ischemia of Infarction

in Internal Carotid Artery Distribution.

Arch Neurol 1979;36:1-4

25.) DeBoer, K., Harmon, R., et al.

Inter- and Intra-examiner Reliability of Leg Length

Differential Measurement: A Preliminary Study.

J Manipulative Physiol Therap 1983;6:61-66

26.) Falltrick, D., Pierson, S.

Precise Measurement of Functional Leg Length Inequality and Changes

Due To Cervical Spine Rotation in Pain-Free Students.

J Manipulative Physiol Therap 1989;12:364-368

27.) Keating, J.

Inter-examiner Reliability of Motion Palpation of the

Lumbar Spine: A Review of Quantitative Literature.

Am J Chiro Med

1989;2:107-110

28.) Nansel, D., Peneff, A., Jansen, R., et al.

Interexaminer Concordance in Detecting Joint-Play Asymmetries

in the Cervical Spines of Otherwise Asymptomatic Subjects.

J Manipulative Physiol Therap 1989;12:428-433

Return to AUTISM

|