Costs of Routine Care For Infant Colic in the UK and Costs

of Chiropractic Manual Therapy as a Management Strategy

Alongside a RCT For This ConditionThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Clinical Chiropractic Pediatrics 2013 (Jun); 14 (1): 1063–1069 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Joyce E. Miller, BS, DC, DABCO

Associate Professor,

Anglo-European College of Chiropractic,

Bournemouth, UK.

jmiller@aecc.ac.uk

This paper is a follow-up cost comparison of the medical and chiropractic care provided in Dr. Miller's RTC study:

Efficacy of Chiropractic Manual Therapy on Infant Colic:

A Pragmatic Single-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012 (Oct); 35 (8): 600–607

This RTC cast new and significant insights into previous colic trials:

In this study, it was found that knowledge of treatment by the parent did not appear to contribute to the observed treatment effects. This was a major criticism of earlier colic studies, and thus may help support their conclusions.

That study revealed that excessively crying infants were 5 times less likely to cry significantly, if they were treated with chiropractic manual therapy, and that chiropractic care reduced their crying times by about 50%, compared with those infants provided solely medical management.

Background: There is a small body of published research (six research studies and a Cochrane review) suggesting that manual therapy is effective in the treatment of infant colic. Research from the UK has shown that the costs of NHS treatment are high (£65 million [USD100 million] in 2001) with no alleviation of the condition.

Objectives: The objectives of this study were to: investigate the cost of the inconsolable nocturnal crying infant syndrome which is popularly known as infant colic in the first 20 weeks of life, estimate the costs of different types of treatment commonly chosen by parents for a colicky infant for a week of care or an episode of care, investigate the cost of chiropractic manual therapy intervention aimed at reducing the hours of infant crying alongside a randomized controlled trial (RCT) showing effectiveness of treatment.

Design: Economic evaluation incorporating a RCT.

Methods: A cost analysis was conducted using data from a RCT conducted in a three-armed single-blinded trial that randomized excessively crying infants into one of three groups: a) routine chiropractic manual therapy (CMT), b) CMT with parent blinded or c) no treatment control group with parent blinded. These costs were compared with costs of caring for infant colic from Unit Costs of Health and Social Care, UK, 2011. It has been widely estimated that 21% of infants in the UK present annually to primary care for excessive crying and this calculated to 167,000 infants (to the nearest 1,000) used in the cost analysis as there were 795,249 infants in the UK in mid–2010 according to the UK Office of National Statistics, 2011.

Results: 100 infants completed the RCT and this resulted in treatment costs of £58/child ($93). An additional cost of GP care of £27.50 was added for initial evaluation of the general health of the child and suitability for chiropractic management, totaling £85.50 per child in the RCT. Clinical outcomes are published elsewhere, but care showed both statistically and clinically significant efficacy in reduced crying time by an average of 2.6 hours, resulting in a crying time of less than two hours a day (reaching "normal" levels which could be classified as non-colic behavior). Cost per child's care was £85.50 extrapolated to £14,278,500 for the full cohort of 167,000. If chiropractic care had been given privately, costs were calculated as £164/child per episode of care and this equaled £27,388,000 for the entire cohort. Medical costs through a normal stream of care amounted to £1,089.91 per child, or £182,014,970 for the cohort (including all costs of care, not just NHS). No benefits of effectiveness were accrued from any of those types of treatment. If the Morris NHS data were extrapolated to 2010, applying wage inflation, the cost would be £118 million (USD180 million) yearly. An episode of an average of four treatments of chiropractic manual therapy with documented efficacy of CMT cost from 8% to 25% of NHS care or routine care.

Conclusion: Chiropractic manual therapy was a cost-effective option in this study. A much larger randomized study of routine medical care versus routine chiropractic care is recommended to determine whether there is confirmation of these findings.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

As effective treatment for children with infant colic remains elusive, the costs of managing the condition is gaining increasing attention. Although it is uncommon for clinicians to be quizzed about the cost-effectiveness of their treatments, [1] particularly where the clinicians’ services are covered by a national health plan, it is increasingly appropriate to ask this question, when prudence in health care expenditure is required.

Cost-effectiveness has been defined as the incremental cost required per additional unit of health benefit produced as compared with the next most effective treatment. [2] This issue is influenced by the seriousness of the condition under treatment, the costs of the condition if untreated, the efficacy of the treatments, durability of treatment along with patient satisfaction with the treatment. [2] Parents choose specific therapies for their child and all have a cost, some easier to identify than others.

In the United Kingdom (UK), there are direct costs to the National Health Service (NHS) for treating the crying baby [3] as well as indirect costs of family travel, lost sleep, lost work time and potential costs of low self-efficacy, depression, anxiety, exhaustion, anger and marital distress and possibly even child maltreatment. [4] An estimate of the direct NHS costs of treating the crying baby less than 12 weeks of age in 2001 in the UK was £65 million (USD100 million) per annum. [3] No therapeutic benefits were accrued from those costs. [3] An updated economic evaluation, applying wage inflation, found that the same costs used in the earlier 2001 report in 2010 cost the NHS an estimated £118 million ($180 million) yearly. [5]

However, the Morris (2001) [3] cost assessment was non-specific as it used only visits to GPs and Health Visitors and only the actual amount of time used to discuss crying problems. Further, the calculations were made for all children born in one given year. A cost assessment using the proportion of infants afflicted with the condition called infant colic using the type of resources parents routinely access is appropriate. An array of treatments for infants with colicky symptoms are chosen by sometimes desperate families. Parents access midwives, GPs, nurses, emergency hospital based services, pediatricians and CAM practitioners. [6] Therefore, it is appropriate to investigate a cost analysis of the condition which includes the variety of treatments without any evidence of efficacy, chosen by parents, along with specific calculations for a type of treatment which has shown some effectiveness, manual therapy. One useful way to determine cost is to follow the costs of care as they occur in a randomised controlled trial. [7] This study endeavored to investigate these costs.

Methods

The objectives were to:

investigate the cost of the inconsolable nocturnal crying infant syndrome which is popularly known as infant colic in the first 20 weeks of life

estimate the costs of different types of treatment commonly chosen by parents for a colicky infant for a week of care or an episode of care

investigate the cost of chiropractic manual therapy intervention aimed at reducing the hours of infant crying relative to a randomised controlled trial showing effectiveness of treatment.

A 20 week time span was chosen because the condition has been said to self-resolve or divert to other symptoms at 24 weeks of age, so for the purposes of this assessment, cost of treatment was calculated for five months (20 weeks) considering the condition starts between 1 and 2 weeks of age. Also, where pertinent, the cost of care for one week was also determined so that a shorter episode of care can be calculated. These decisions were made in the effort to underestimate rather than overestimate the costs. That said, self-resolution of the condition has often been disputed and many long-term effects have been noted. [8]

Unfortunately, there is a risk for maltreatment in these cases and a recent report states that this affects 6% of excessively crying infants. [9] It must be noted that excessive crying is the chief reason that parents give for maltreatment of their child and the child less than one year of age is the most commonly abused member of society. [10] Therefore this is also included in the calculations and presented as an average of cost per child when spread over the entire cohort.

Because each cost is independently calculated, there is flexibility in choosing which therapies or issues are appropriate in any individual case. For example, costs of hypo-allergenic formula were calculated for only 5% of the colic population, as this was thought to be realistic considering the estimate of 5–15% occurrence of milk allergy in the young population. [11] However, NHS guidelines suggest a week’s trial for all colic babies under clinical guidance and this number is calculated as well. Also, the figure of 1% of colic children was used to calculate the costs of non-allergenic (amino acid) formula. All are appropriate as it is realistic that 5% of the population may require a full course of hypo-allergenic formula and NICE guidelines recommend a week’s trial for all colicky infants, and a small percentage require non-allergenic formula. The clinician may decide which are most appropriate, although realistically, all these costs may be incurred.

According to the Office for National Statistics, in 2011 there were 795,249 infants in the UK in mid-2010. Freedman et al. in 2009 [12] calculated that 21% of infants present to health care for excessive crying and this resulted in the 167,000 infants (calculated to the nearest 1,000) used for the cost analysis. These numbers were used for calculations to answer the first two research questions. It must be kept in mind that Morris, in 2001, reported numbers for all infants. [3]

The third question was answered by using data from the RCT investigating manual therapy as an intervention into the condition of infant colic, a three-armed single-blinded controlled trial conducted on the south coast of England between 2010 and 2011. [13]

Results

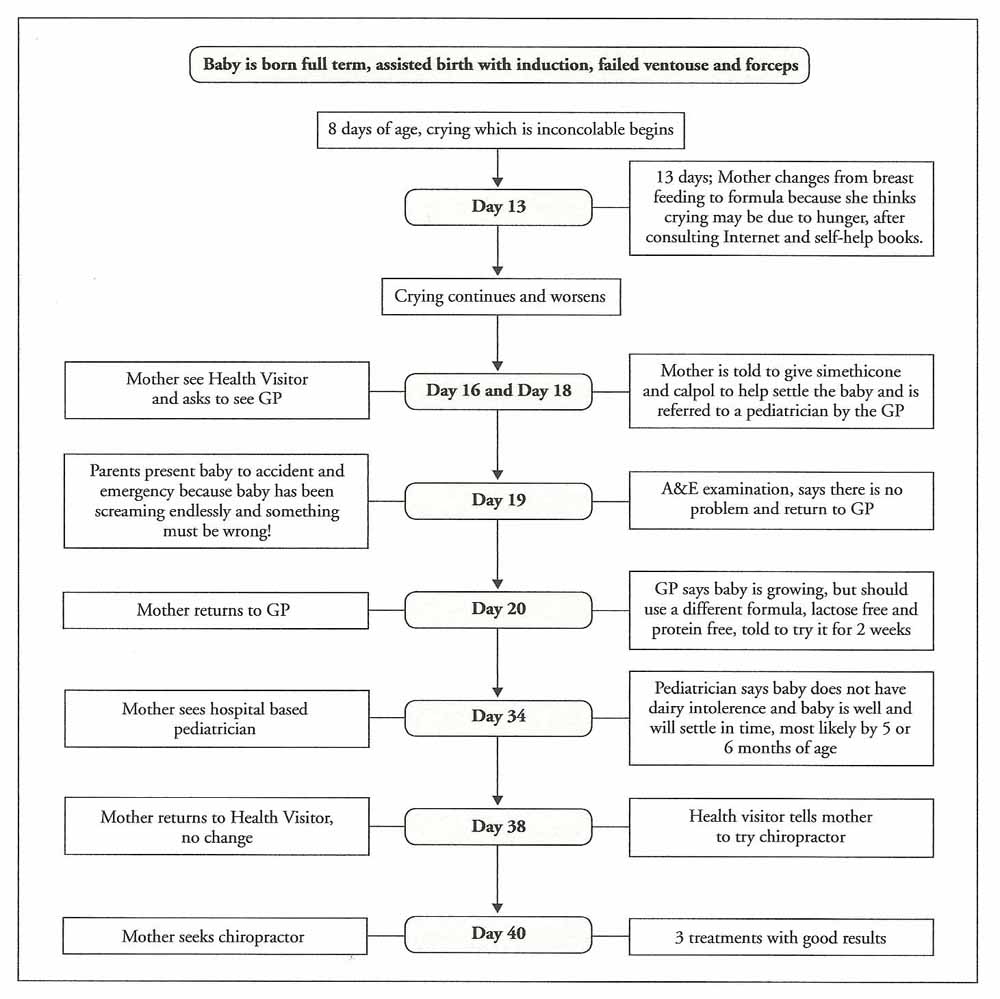

Figure 1

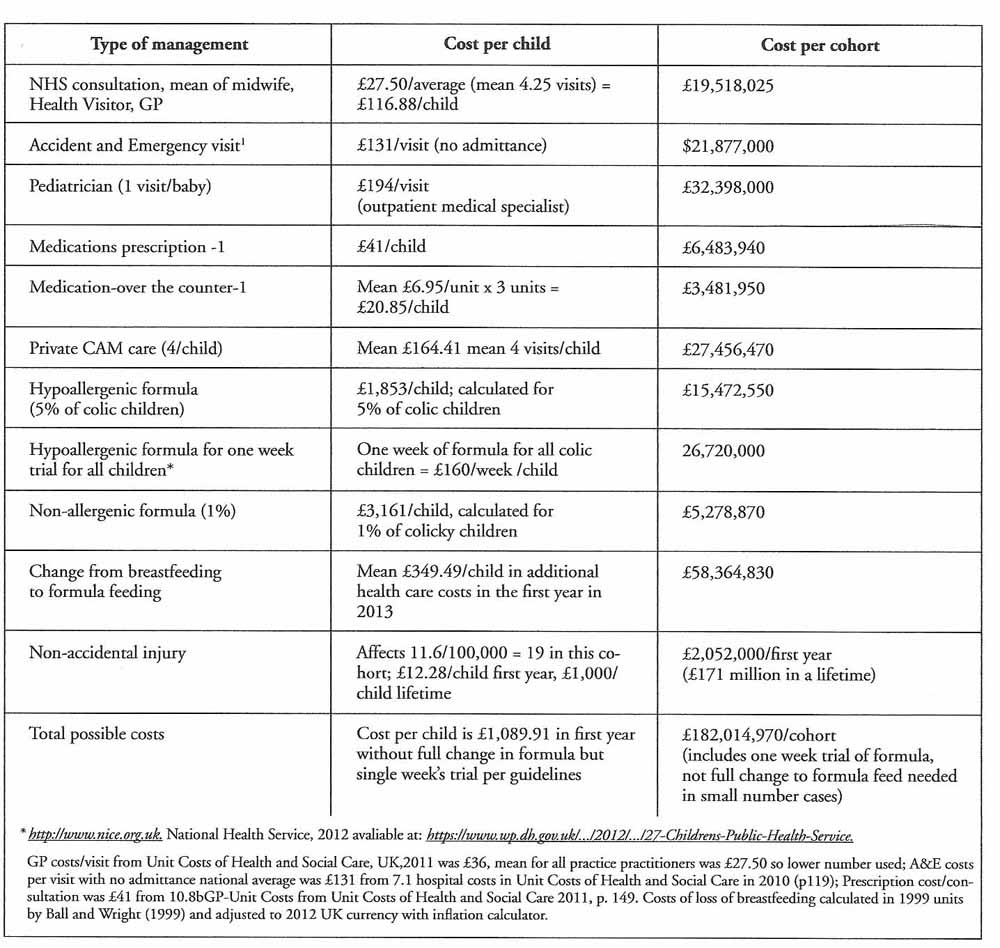

Table 1

Table 2 Figure 1 is the author’s conception of a “typical” pathway chosen by parents of a child with infant colic and is based upon clinical experience as well as research literature. [6, 14]

Table 1 estimates potential costs for a cohort of infants with infant colic in the UK. According to systematic reviews of treatments for infant colic, these treatments resulted in no significant recovery. [15–17] This table demonstrates the potential costs of a cohort of colicky infants in a possible flow-through typical types of health care along with potential costs of infant colic including change in feeding, stoppage of breast feeding and even non-accidental injury. Costs have been added for a total potential for routine costs that might accrue in a cohort of afflicted infants.

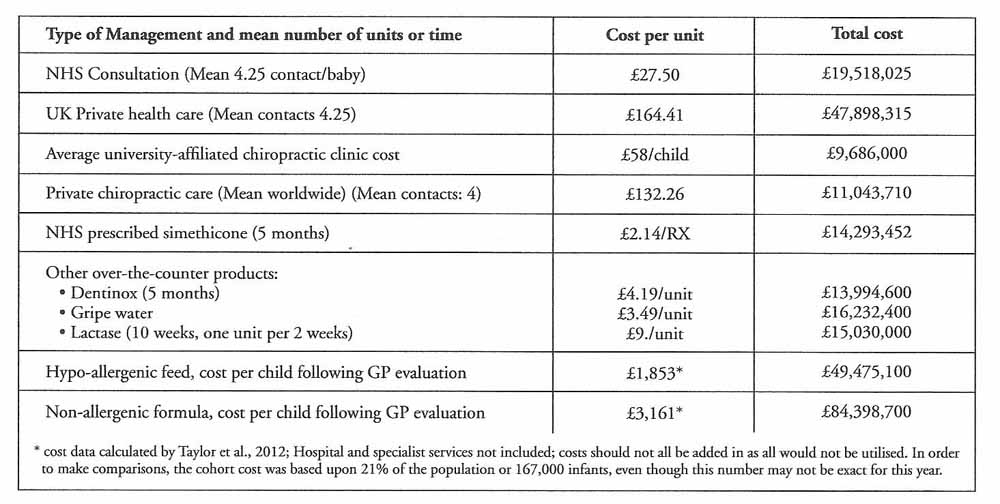

Table 2 differs from Table 1, in that it depicts per unit costs that parents might choose for their afflicted child. Although it does use the multiplyer factor of the full cohort of infants with colic, it doesn’t purport that this is a cohort of children moving through care, but only depicts some of the more common types of care which are chosen, so that costs can be compared. The reader may pick and choose which of these to add together for routine costs. In the cost analysis paralleling a recent RCT, [12] costs were as follows:

One GP visit to rule out illness and send the child to the university affiliated clinic: cost per child £27.50; cost for 100 children: £2,750

Mean of 4 chiropractic treatments (£14.50/treatment) for child at £58/child = £5,800.

Total cost was £8550/100 children which is £85.50/child

If this were extrapolated to the entire cohort, the cost for chiropractic care for every child who suffered from infant colic in 2010 would be £14,278,500 (approximately $22 million) for an episode of manual treatment.

This cost resulted in an average of 2.6 hours reduction in infant crying, bringing the weekly crying to a “normal” amount which is less than a colic diagnosis. The cost of manual therapy per hour reduction in crying was £33 ($51).

Discussion

This study sought to review costs of one of the most common conditions of infancy — colic. The costs of treatment of this condition are high and most are unrelated to any effective treatment. Only chiropractic manual therapy has demonstrated sufficient efficacy in this condition to be given an effectiveness rating of “moderate” by Cochrane reviewers. [18]

Although an attempt was made to review the wide range of treatments chosen by parents, perhaps more nonconventional therapies should be reviewed as well, known as complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). Parents in the USA spent $149 million (£90 million) for CAM therapies or remedies for their children in 1996. [19] That was almost two decades ago and by all counts, CAM has grown significantly since then. If 3.7% of those visits were allotted to chiropractic, [20] the portion was $5.5 million (£3.3) in 1996, which is equivalent to $8 million (or £5 million) in 2012 spent by parents on chiropractic manual therapy for children. By all counts, CAM usage, particularly manual therapy usage has increased since then and economics should be reconsidered. [20]

Manual therapy has been found to be cost-effective in other studies. [21–24] However, there has been no attempt at investigation of a cost-benefit analysis of chiropractic manual therapy for the treatment of the infant inconsolable nocturnal crying infant syndrome (a proposed moniker to replace the outdated term, infant colic).

Of course, even a treatment that has shown effectiveness in a blinded RCT and a Cochrane review does not guarantee success in every child. However, the weakest manual therapy RCT resulted in 43% less crying [25] and safety is more or less assured from the track record [26] of the therapy as well as the close monitoring of the baby and family. Close monitoring over the difficult weeks may be one of the benefits for the family and society, which may keep the child safe, even if treatment is not completely efficacious. [9]

If examination by the GP to determine that no other illnesses were present and if no further treatment beyond manual therapy were sought, this could result in a savings of £50,721,500 in 2001 (approximately £60 million in 2012 [USD 96 million]). The annual cost of manual therapy is approximately equivalent to the annual cost of the most common drug treatment, simethicone alone at current rates. Although the two treatments, simethicone and manual therapy cost approximately the same, three double blind studies show no effectiveness for that medication [15–17] while manual therapy has shown moderate effectiveness for the condition. [18] Of course, a £60 million savings is a small number compared to the NHS annual budget of £104 billion in 2010 [27] and perhaps should be looked at more in light of helping families than pure economic savings.

It is, perhaps, difficult to contemplate a deviation of care from the well-established medical model with all of its advanced technological capabilities and resources, particularly in dealing with the needs of a newborn. Manual skills, which individualize variable palpatory pressures may uncover functional problems in the infant. [28] The final common pathway of the gentle manual therapeutics used for infants is one of release, joint release when immobility is observed and myofascial release when a muscle is tonic. When these were factors preventing normal biomechanical actions in the child,(s)he tends to feel relief. Treatments are low-tech and thus, relatively, low cost.

Chiropractic manual therapy (CMT) doesn’t include any usage of drugs or medications. However, CAM users are more likely to be medication users as well. [19, 20] This would raise the costs of an episode of care; it should also alert CAM practitioners that the child could be suffering from a side-effect from medication and this should be carefully observed. Cincotta and colleagues [29] pointed out that there is potential for cross-reactivity in medications with CAM herbal or homeopathic remedies (anything that is taken internally) and that this isn’t an issue with purely mechanical therapies such as chiropractic and this is one less risk with manual therapy. Herbal and homeopathic medicines have shown life-threatening episodes with infants. [30, 31] Likewise, Birdee and colleagues [20] stressed concern of drug/herb interactions as over-all CAM use was associated with medication use in the last three months and this might lead to significant adverse effects.

One of the longest-term potential costs of ill-health is a change from breastfeeding to formula feeding. A diagnosis of colic has been shown to predict shorter duration of breastfeeding, [32] and this, perhaps, could be argued to be the greatest cost of all, since it predicts not only higher costs for medical care in the first year of life, but may also continue lifelong. [32–34]

There are limitations to this study. It is linked to a RCT and although this is a common method to determine cost effectiveness, it is not the only method. [35] It should be kept in mind that any specific therapy may be part of a bundle of therapies and total costs may be difficult to unpick. The main limitation in cost-effectiveness studies is the accuracy of the data upon which the review is based. In this case, the review is completely transparent, so that if any new costs surface, they can be added or changed. Anyone who feels that some types of care are not routinely accessed can simply delete them from the estimate. As usual, caution should be used when interpreting these data as with any very large numbers, there is room for considerable inaccuracy and these should be looked upon as trends as much as specific numbers. The trends, however, are quite clear. The costs of the excessively crying baby are very high and a small demonstration project study may be warranted to determine whether chiropractic manual therapy continues to show promise in reducing these costs whilst providing relief for the child and family.

Once an infant is determined to be healthy and suffering from no illness, the most cost-effective choice may be a short trial of chiropractic manual therapy. So far, the performance of manual therapy is better than other treatments and in a worst case scenario, a baby not helped for this condition, has extremely low risk of coming to any harm with this type of therapy.

REFERENCES:

Phillips B.

Towards evidence based medicine for paediatricians: But at what cost?

Archives Disease of Childhood Practice Education 2008:93(4):129Kim JJ.

The role of cost-effectiveness in U.S. vaccination policy.

New England Journal of Medicine 2010;10.1056/NEJMp1110539. NEJM.org.Morris S, St James-Robert I, Sleep J, Gillham P.

Economic evaluation of strategies for managing crying and sleeping problems.

Archives of Disease in Childhood 2001;84:15-19Papousek M and von Hofacker N.

Persistent crying in early infancy: a non-trivial condition of risk for the developing mother-infant relationship.

Child: Care Health and Development 1998;5:395-424Groom C, Jolliffe C, Miller J, Nylund C, Wilson A.

Cost effectiveness of chiropractic treatment for infant colic.

Proceedings of the European Chiropractors Union 2013 Conference Barcelona, Spain, May, 2013McCallum SM, Rowe HJ, Gurrin LC ,Quinlivan JA, Rosenthal DA, Fisher JRW.

Unsettled infant behaviour and health service use: A cross-sectional community survey in Melbourne, Australia.

J Paediatr Child Health 2011;47:818-23Hollinghusrt S, Redmond N, Costeloe C, Montgomery A, Fletcher M, Peters TJ, Hay AD.

Paracetamold plus ibuprofen for the treatment of fever in children (PITCH): economic evaluation of a randomised controlled trial.

British Medical Journal 2008;337:734-737Wolke D, Rizzo P, Woods S.

Persistent infant crying and hyperactivity problems in middle childhood.

Pediatrics 2002;109(6):1054-60Reijneveld SA, van der Wal M, Brugman E, Hira Sing R, Verloove- Vanhorick S.

Infant crying and abuse.

Lancet 2004;364:1340-2Carbaugh SF.

Understanding shaken baby syndrome.

Advances in Neonatal Care 2004; 4:105-114Vandenplas Y, Brueton M, Dupont C, Hill D, Isolauri E, Koletzko S, Oranje AP, Staiano A.

Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of cow’s milk protein allergy in infants.

Archives of Disease in Childhood 2007; 92:902-908Freedman SB, Al-Harthy N, Thull-Freedman J.

The crying infant: diagnostic testing and frequency of serious underlying disease.

Pediatrics 2009;123(3): 841-48Miller J, Newell D, Bolton J.

Efficacy of Chiropractic Manual Therapy on Infant Colic:

A Pragmatic Single-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012 (Oct); 35 (8): 600–607Bromfield L, Holzer P.

A national approach for child protection – Project Report Commissioned by the Community and Disability Services Ministers’ Advisory Council.

In: Australian Government Department of Families CSaiA-, editor.:

National Child Protection Clearinghouse,

Australia Institute of Family Studies; 2008Lucassen PL, Assendelft WJ, Gubbels JW, et al.,

Effectiveness of treatment for infantile colic: systematic review.

British Medical Journal 1998;23:1563-1569Lucassen P.

Colic in infants.

Clinical Evidence 2010;02:309Husereau D, Clifford T, Aker P, Leduc D, Mensinkai S.

Spinal Manipulation for Infantile Colic

Ottawa: Canadian Coordinating Office for Health Technology Assessment; 2003.

Technology report no 42Dobson D, Lucassen PLB, Miller J, Vlieger, AM, Prescott P, George Lewith G.

Manipulative therapies for infant colic.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012Yussman SM, Ryan SA, Auinger P, Weitzman M.

Visits to complementary and alternative medicine providers by children and adolescents in the United States.

Ambulatory Pediatrics 2004;4(5):429-435Birdee GS, Phillips RS, Davis RB, Gardiner P.

Factors associated with pediatric use of complementary and alternative medicine.

Pediatrics 2010;125(2):249-256Doran CM, Chang DHT, Kiat H, Bensousssan A.

Review of economic methods used in complementary medicine.

Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 2010;16(5):591-595Korthals-deBos IBC, et al.

Cost Effectiveness of Physiotherapy, Manual Therapy, and General Practitioner Care

for Neck Pain: Economic Evaluation Alongside a Randomised Controlled Trial

British Medical Journal 2003 (Apr 26); 326 (7395): 911Williams NH, et al.

Cost-utility analysis of osteopathy in primary care: results form a pragmatic randomized controlled trial.

Family Practice 2004;21:643-650Gurden M, Morelli M, Sharp G, Baker K, Betts N and Bolton J.

Evaluation of a general practitioner referral service for manual treatment of back pain and neck pain.

Primary Health Care Resource Development 2012Olafsdottir E, Forshei S, Fluge G, Markestad T:

Randomised Controlled Trial of Infantile Colic Treated With Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation

Archives of Disease in Childhood 2001 (Feb); 84 (2): 138–141Humphreys BK.

Possible Adverse Events in Children Treated By Manual Therapy: A Review

Chiropractic & Osteopathy 2010 (Jun 2); 18: ; 12Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK,.

Office for national statistics. [Online] 2 May 2012.

[Cited: 13 March 1013.]

http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171766_264293.pdfMarchand A.

Chiropractic Care of Children from Birth to Adolescence and Classification of Reported Conditions: An Internet Cross-Sectional Survey of 956 European Chiropractors

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012 (Jun); 35 (5): 372–380Cincotta DR, Crawford NW, Lim A, Cranswick NE, Skull S, South M, Powell CV.

Comparison of complementary and alternative medicine use: reasons and motivations between two tertiary care children’s hospitals.

Archives of Disease in Childhood 2006;91(2):153-8Aviner S, Berkovitch M, Dalkian H, Braunstein R, Lomnicky Y, Schlesinger M.

Use of a homeopathic preparation for “infantile colic” and an apparent life-threatening event.

Pediatrics 2010;125(2).

Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/125/2/e318Saper RB,Kales SN, Paquin J., et al.

Heavy metal content of ayurvedic herbal medicine products.

Journal American Medical Association 2004;292(23):2868-2873Howard CR, Lanphear N, Lanphear BP, Eberly S, Lawerence RA.

Parental responses to infant crying and colic: the effect on breastfeeding duration.

Breastfeeding Medicine 2006;1(3):146-155Ball TM and Wright Al.

Health care costs of formula-feeding in the first year of life.

Pediatrics 1999;103(4Pt2):870-6Taylor RR, Sladkevicius E, Panca M, Lack G, Guest JF.

Cost-effectiveness of using an extensively hydrolysed formula compared to an amino acid formula as first-line treatment for cow milk allergy in the UK.

Pediatric Allergy and Immunology 2012;23(3):240-249Hollinghurst S, Redmond N, Costeloe C, Montgomery A, Fletcher M, Peters TJ, Hay AD.

Paracetamol plus ibuprofen for the treatment of fever in children (PITCH): economic evaluation of a randomised controlled trial.

British Medical Journal 2008;337:734-737Return to COLIC

Return to PEDIATRICS

Since 2-02-2014

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |