Wellness-related Use of Common Complementary

Health Approaches Among Adults:

United States, 2012This section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: National Health Statistics Report 2015 (Nov 4); (85): 1–12 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Barbara J. Stussman, B.A., Lindsey I. Black, M.P.H., Patricia M. Barnes, M.A.,

and Tainya C. Clarke, Ph.D., M.P.H., and Richard L. Nahin, Ph.D., M.P.H.,

National Institutes of Health

National Center for Health StatisticsObjective This 12 page National Institutes of Health report presents national estimates of selected wellness-related reasons for the use of natural product supplements, yoga, and spinal manipulation among U.S. adults in 2012. Self-reported perceived health outcomes were also examined.

Methods Data from 34,525 adults aged 18 and over collected as part of the 2012 National Health Interview Survey were analyzed for this report. In particular, whether adults who used selected complementary health approaches did so to treat a specific health condition or for any of five wellness-related reasons was examined, as well as whether these adults perceived that this use led to any of nine health-related outcomes. Sampling weights were used to produce national estimates that are representative of the civilian noninstitutionalized U.S. adult population.

Results Users of natural product supplements and yoga were more likely to have reported using the approach for a wellness reason than for treatment of a specific health condition, whereas more spinal manipulation users reported using it for treatment rather than for wellness. The most common wellness-related reason reported by users of each of the three approaches was for ‘‘general wellness or disease prevention.’’ The majority of users of all three health approaches reported that they perceived this use improved their overall health and made them feel better. Yoga users perceived higher rates of all of the self-reported wellness-related health outcomes than users of natural product supplements or spinal manipulation.

Keywords: disease prevention • mind–body • nonvitamin, nonmineral dietary supplements • National Health Interview Survey

From the FULL TEXT Article

Introduction

Complementary health approaches include an array of health care systems, therapies, and products with a history of use or origins outside of mainstream medicine. Examples include yoga, chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation, and acupuncture. Previous studies have shown that many individuals use complementary health approaches for disease prevention and to improve health and wellbeing [1, 2], or to relieve symptoms associated with chronic diseases or the side effects of conventional medicine(s) [3, 4]. Persons who use complementary health approaches often have a holistic health philosophy, want greater control over their own health, and practice a ‘‘wellness lifestyle’’ [5, 6]. Previous studies have also shown that different approaches are used for different reasons [7–9]. For example, Hawk et al. 2011 [7] found that nearly 60% of users of massage therapy did so for reasons other than treatment of a specific health condition, whereas only 31% of naturopathy users, 15% of acupuncture users, and 18% of chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation users sought care for reasons other than to treat a specific health condition.

Table This report examines a range of survey questions specifically developed to capture wellness-related reasons and perceived health outcomes reported by individuals using selected complementary health approaches. Previous qualitative research conducted with persons who use complementary health approaches led to the development of new questionnaire items that were included in the 2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) [10]. Respondents were asked separately about health-related reasons for using each complementary health approach and whether they perceived that this use resulted in specified health outcomes. For the current analyses, five questionnaire items that captured wellness-related reasons for using the approach, and nine items that captured wellness-related health outcomes for three commonly used complementary approaches (natural product supplements, yoga, and chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation [subsequently referred to in this report as ‘spinal manipulation’ for the sake of brevity]) among adults aged 18 and over were examined (Table). These three approaches were chosen for analysis for two reasons: They were among the most commonly used in 2012 [11] (17.7% of adults used natural product supplements, 8.7% used yoga, and 8.4% used spinal manipulation in the previous 12 months); and they represent three major types of complementary health approaches: natural products (natural product supplements), mind–body approaches (yoga), and practitioner-based approaches (spinal manipulation). Additionally, data on whether these three approaches were used for treatment purposes are presented. Other reasons for using complementary health approaches and outcomes from their use were assessed in the 2012 survey but are not considered wellness-or treatment-related and, thus, are not included in the current analyses.

This report builds on previous research by examining an expanded list of wellness-related reasons that prompted individuals’ use of complementary approaches, as well as highlighting self-reported perceived health outcomes. This analysis will allow researchers and practitioners to better understand not only wellness and treatment reasons for using complementary health approaches, but also nuances in wellness-related use across the three commonly used approaches.

Methods

Data source

Data in this report come from the 2012 Adult Alternative Medicine supplement to NHIS. NHIS is a multipurpose health survey of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. It is conducted continuously for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics by trained interviewers from the U.S. Census Bureau. Data are collected in person at the respondent’s home using computer-assisted personal interviewing, but follow-ups to complete interviews may be conducted over the telephone.

The survey consists of both a core set of questions that remain relatively unchanged from year to year as well as supplemental questions that are not asked every year. The core consists of four main components: Household Composition Section, Family Core, Sample Adult Core, and Sample Child Core. The Household Composition Section collects basic demographic and relationship information about all household members of all families living in a household. The Family Core Section collects sociodemographic and basic health information about all family members. For the Sample Adult Core, one adult per family (the sample adult) is randomly selected to respond to detailed health questions. For the Sample Child Core, a knowledgeable adult (usually the parent) responds to detailed health questions for one randomly selected child per family (the sample child). More information on NHIS is available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm [12].

In 2012, NHIS fielded the Adult Alternative Medicine supplement to collect information on the use of complementary health approaches in the United States. This supplement followed the Sample Adult questionnaire. All sample adults were asked broadly about the use of more than 20 different complementary health approaches. For persons who reported using a particular approach, more detailed questions were asked about this use, such as sources of information about the approach and disclosure to a conventional provider. Respondents were also asked a series of questions about reasons for use and self-reported perceived health outcomes resulting from the use of specific approaches (Table). Respondents were asked to respond yes or no to each reason or outcome. Respondents with missing data for a particular reason or outcome were excluded from the analysis of that item. Reasons were not mutually exclusive and respondents could report a wellness and a treatment reason in addition to multiple wellness reasons. In the event that adults used more than three complementary health approaches (3.2% of adults; 10.9% of adults who used complementary health approaches), they were first asked to select the top three most important approaches for their health, and then asked to report reasons for the use of these approaches only. The use of the approaches analyzed in this report are underestimated to the extent that adults using more than three approaches did not choose natural product supplements, spinal manipulation, or yoga as most important to health.

The first self-reported perceived health outcomes examined for this report were whether respondents’ use of the named complementary health approach motivated them to do any of the following:

- Exercise more regularly

- Eat healthier

- Cut back or stop drinking alcohol

- Cut back or stop smoking cigarettes

The items on alcohol and smoking were asked only of adults who reported that they were current drinkers or smokers in the Core questionnaire. Other self-reported perceived health outcomes examined in this report include:

- Reduced stress or relaxation

- Improved sleep

- Felt better emotionally

- Eased coping with health problems

- Improved overall health and made you feel better

Respondents were asked to say yes or no to each item.

Analyses in this report were based on data from 34,525 sample adults aged 18 and over, 4,400 of whom reported that they had taken natural product supplements in the past 30 days, 2,729 who reported practicing yoga in the past 12 months, and 2,785 who reported seeing a practitioner for spinal manipulation in the past 12 months. Use of yoga was restricted to individuals who had used deep breathing or meditation as part of yoga. The conditional response rate for the sample adult questionnaire was 79.7% (the number of completed sample adult interviews divided by the total number of eligible sample adults), and the final response rate was 61.2% (the conditional response rate multiplied by the final family response rate).

Statistical analyses

Estimates in this report were calculated using the sample adult sampling weights and are representative of the noninstitutionalized population of U.S. adults aged 18 and over. Data weighting procedures are described in more detail elsewhere [13]. Point estimates, and estimates of their variances, were calculated using SAS-callable SUDAAN version 11.0.0, a software package that accounts for the complex sample design of NHIS [14]. The denominators used in the calculation of percentages for reasons for use of complementary health approaches were the number of adults who reported use of the specific complementary health approach as any of their top three most important approaches used for health reasons within the past 12 months. Respondents with missing data or unknown information were excluded from the analysis. Estimates presented are not age-adjusted in order to capture the actual prevalence of reasons persons were using selected complementary health approaches. Estimates were compared using two-sided t tests at the 0.05 level. Terms such as ‘‘greater than’’ and ‘‘less than’’ indicate a statistically significant difference. Terms such as ‘‘not significantly different’’ or ‘‘no difference’’ indicate that no statistically detectable differences were seen between the estimates being compared. Reliability of estimates was evaluated using the relative standard error (RSE), which is the standard error divided by the point estimate. Estimates with RSEs less than or equal to 30% were considered reliable.

Strengths and limitations of data

A major strength of these analyses is that the data are from a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults, allowing for population estimates. The large sample size allows for estimation of the reasons and outcomes for the use of selected complementary health approaches collected in NHIS. Furthermore, it is unlikely that the current data omit common reasons and perceived outcomes given that the questionnaire items were written based on input from complementary approach users [10].

There are several limitations to this study. Pretesting of the questionnaire revealed that some respondents did not adhere to the 12-month time frame stated in the question and reported on their general use of the complementary health approach. Although the items were designed to differentiate between reasons for beginning use and outcomes from using complementary health approaches, pretesting revealed that some respondents interchanged these concepts when answering. In addition, this study is limited by the cross-sectional nature of the survey, which does not support conclusions from causal associations. Responses are dependent on participants’ recall of complementary health approaches and their willingness to report their use accurately.

Results

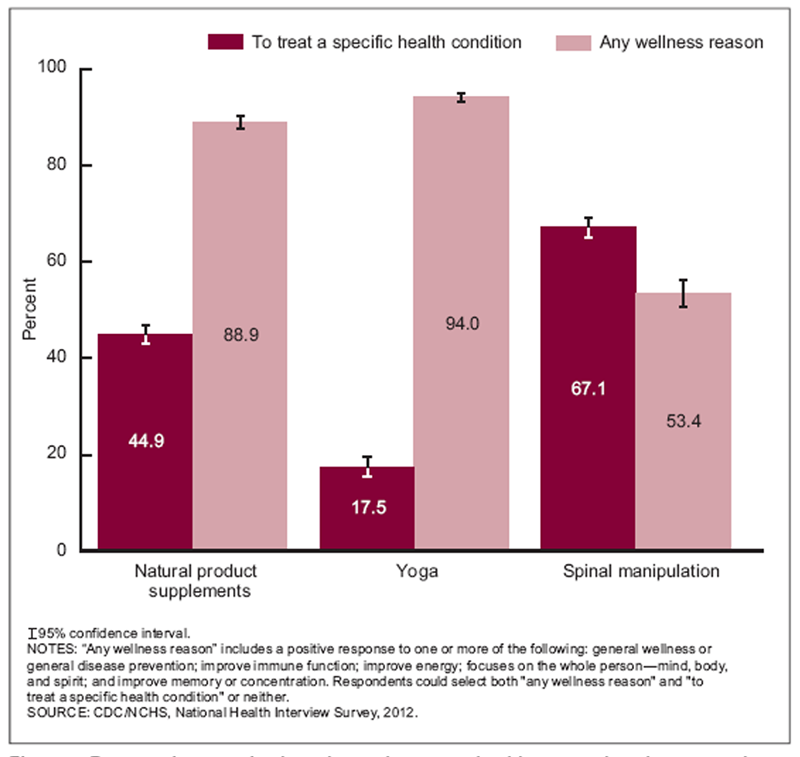

Figure 1

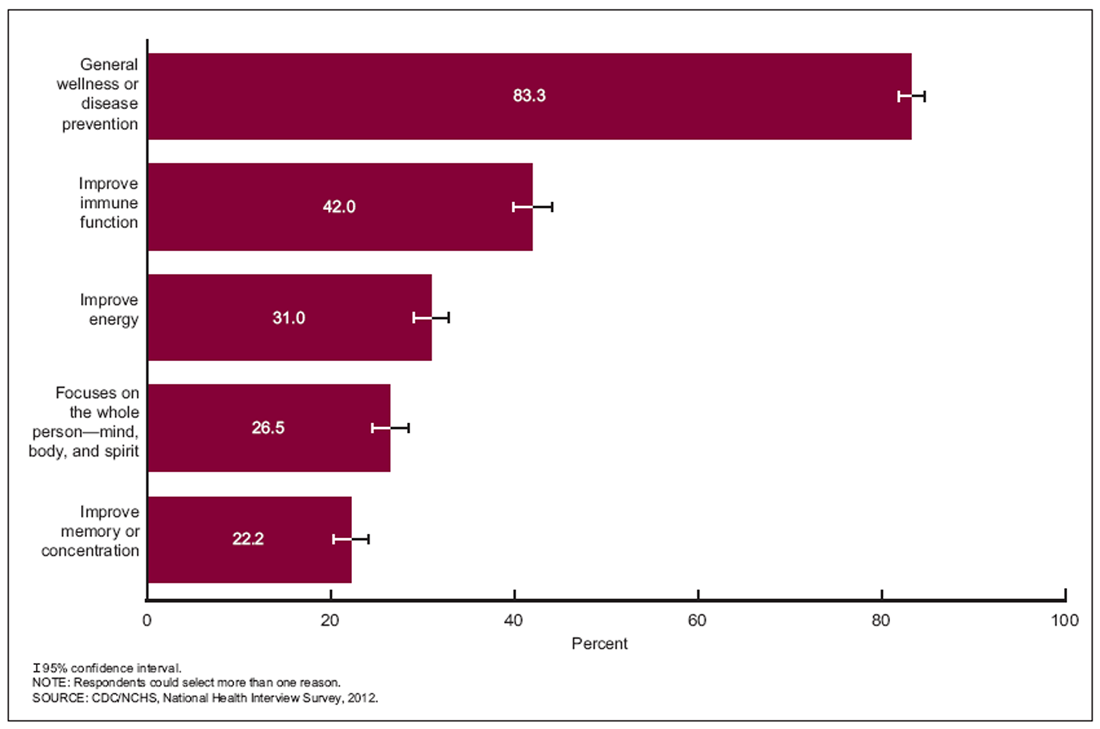

Figure 2

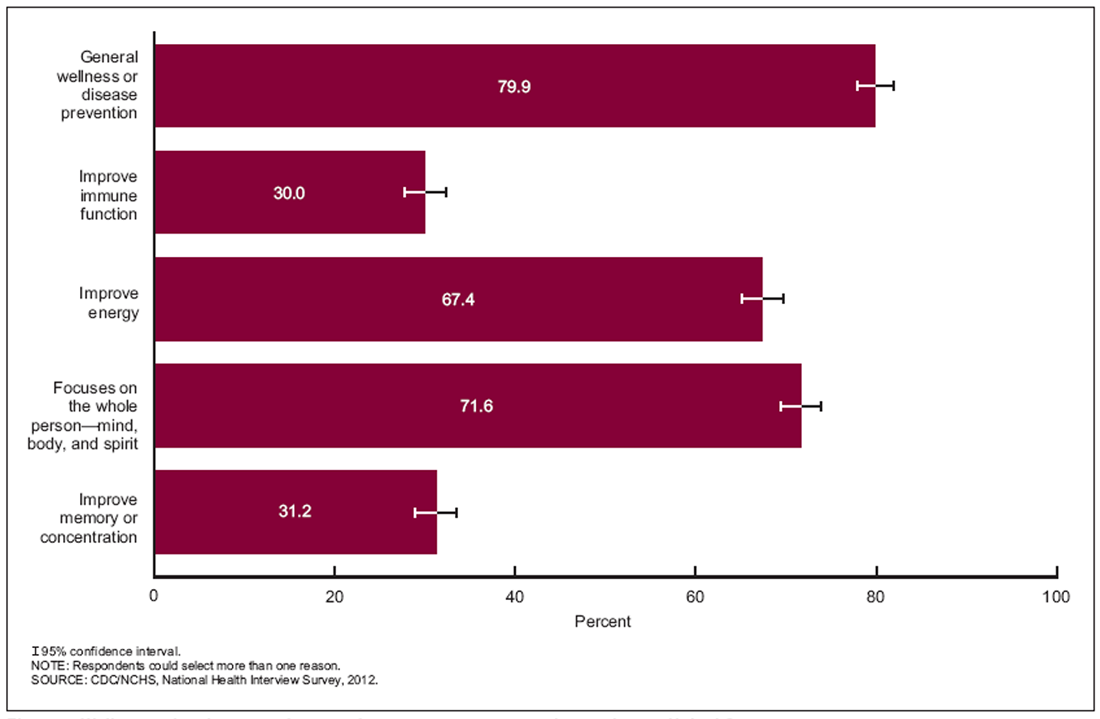

Figure 3

Figure 4 Respondents who used or saw a practitioner for any complementary health approach in the previous 12 months were asked in separate survey questions if the modality was used for one or more wellness-related reasons, and if it was used to treat a specific health problem or condition. The percentages of adults who used natural product supplements, yoga, or spinal manipulation for these reasons are presented in Figure 1.

Figures 2-4 present the wellness-related outcomes for the use of natural product supplements, yoga, and spinal manipulation, respectively.

Natural product supplements and yoga were used for wellness more often than for treatment of a specific health condition, whereas spinal manipulation was used more often for treatment (Figure 1).

Users of natural product supplements were almost twice as likely to take these supplements for one or more wellness-related reasons compared with treatment of a health condition.

Adults who used yoga were more than five times more likely to report wellness reasons than treatment of a health condition. In contrast, more than 60% of users of spinal manipulation reported doing so to treat a specific health condition, and more than 50% did so for general wellness or disease prevention.

More than four out of five users of natural product supplements reported that they took these supplements for general wellness or disease prevention (Figure 2). More than 40% of persons who took natural product supplements reported that they did so to improve immune function.

More than one in every four persons who used natural product supplements did so because they perceive it focuses on the whole personmind, body, and spirit.

Compared with other wellness-related reasons, relatively few natural product supplement users cited improvement of memory or concentration as a reason (22.2%).

Three of the five wellness-related reasons were reported by the majority of yoga users. Approximately four out of five said that they use yoga for general wellness or disease prevention, and more than two-thirds reported that they use yoga because they perceive it focuses on the whole personmind, body, and spirit, or to improve energy (Figure 3).

Approximately 30% of persons who used yoga reported that they did so because they expected improved immune function or improved memory or concentration.

General wellness or disease prevention was the most common wellness-related reason chosen by spinal manipulation users (43.2%) (Figure 4).

One in four spinal manipulation users selected ‘‘because it focuses on the whole personmind, body, and spirit,’’ as a reason for using the approach.

Less than 20% of spinal manipulation users did so for the expectation of improved energy, improved immune function, or improved memory or concentration.

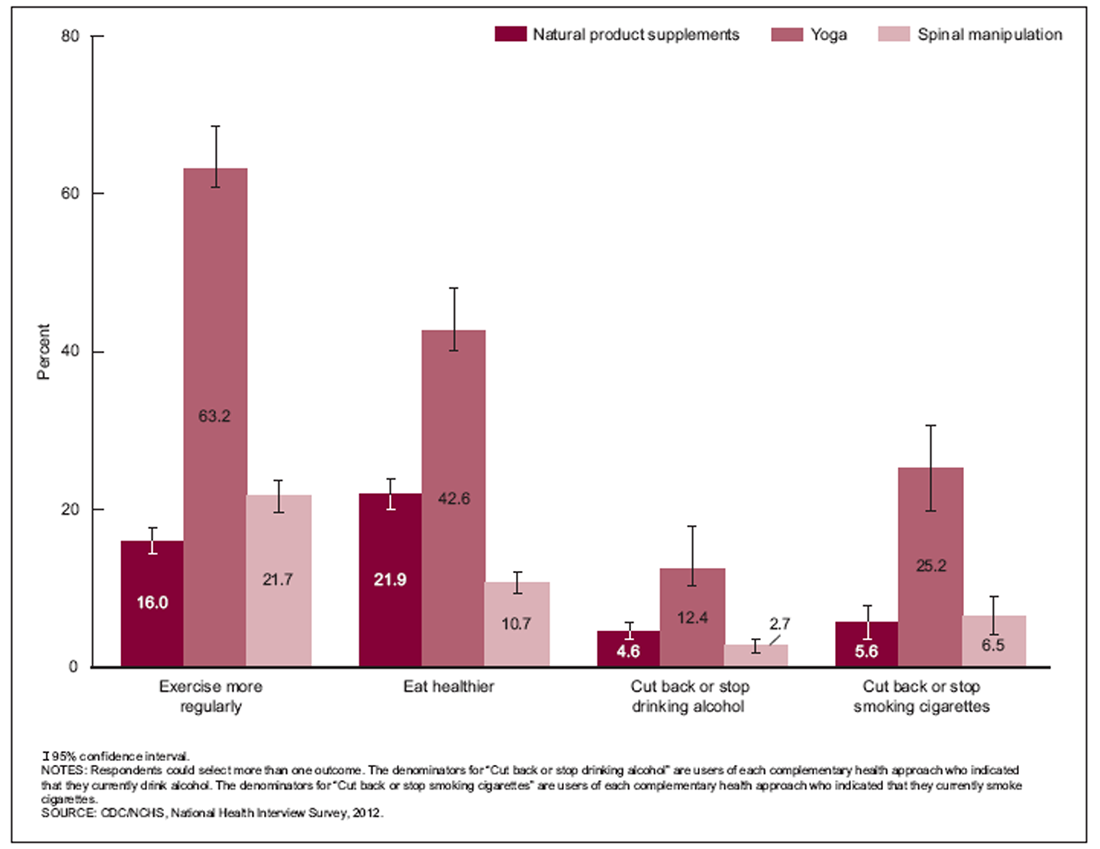

Figure 5 Figure 5 shows estimates for self-reported perceived health behavior outcomes for users of natural product supplements, yoga, and spinal manipulation. Analyses regarding alcohol and smoking use were restricted to users of these complementary health approaches who indicated earlier in the survey that they currently drank alcohol or smoked cigarettes. This restriction was necessary due to how the data were collected at the time of the interview. Thus, users of these complementary health approaches who were motivated to quit drinking or smoking as a result of the approach and were successful doing so are not included in the estimates.

Yoga users perceived higher rates of each of the four health behavior outcomes examined than did users of natural product supplements or spinal manipulation (for exercise more regularly: 63.2% compared with 16.0% and 21.7%, respectively; for eat healthier: 42.6% compared with 21.9% and 10.7%, respectively; for cut back or stop drinking alcohol: 12.4% compared with 4.6% and 2.7%, respectively; and for cut back or stop smoking cigarettes: 25.2% compared with 5.6% and 6.5%, respectively).

More than 63% of yoga users perceived that they were motivated to exercise more regularly after using yoga. In contrast, only 16.0% of natural product supplements users and 21.7% of spinal manipulation users reported being motivated to exercise more regularly.

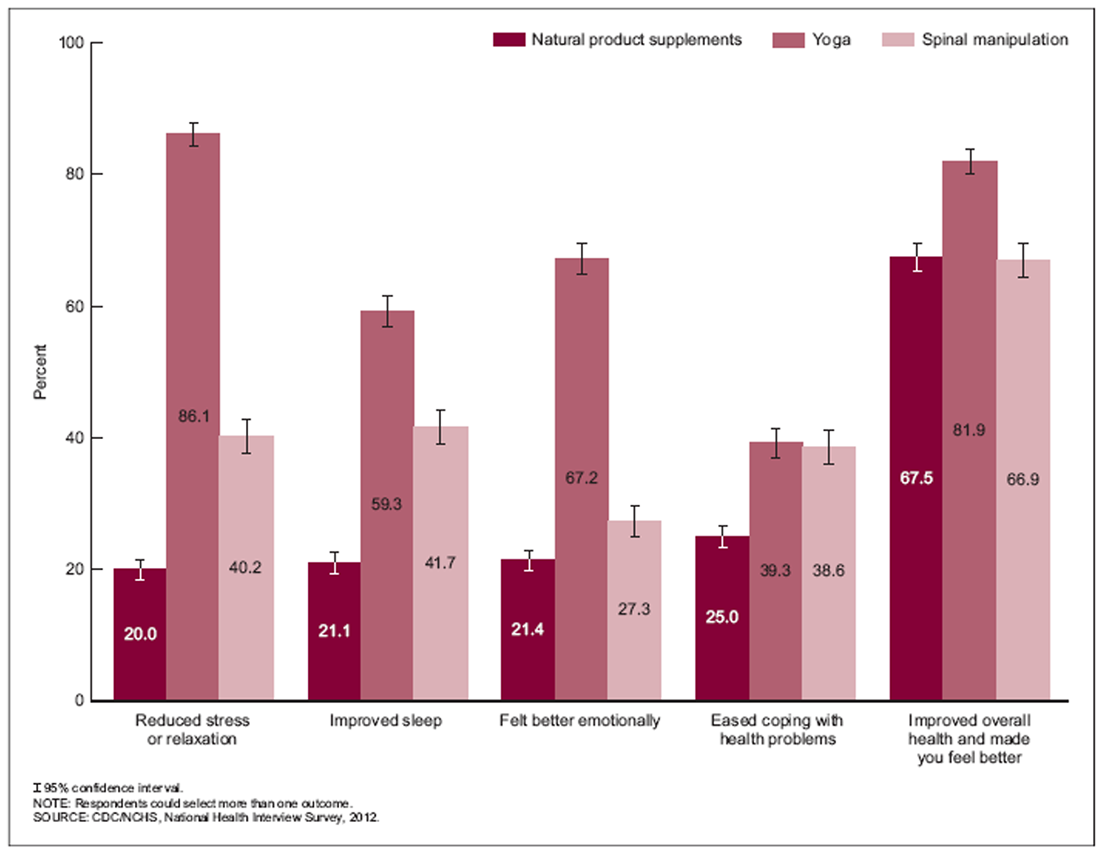

Figure 6 Figure 6 presents five additional wellness-related outcomes perceived by respondents who used complementary health approaches in the previous 12 months.

More than two-thirds of users of all three approaches reported improved overall health and feeling better as a result of using the approach (Figure 6).

More than 80% of yoga users perceived reduced stress as a result of using yoga.

Fewer than one in four users of natural product supplements perceived reduced stress, better sleep, or feeling better emotionally as a result of using natural product supplements.

Yoga users were more likely to report feeling better emotionally as a result of using the approach (67.2%) than were users of natural product supplements (21.4%) or spinal manipulation (27.3%).

Approximately 4 in 10 users of spinal manipulation perceived a reduced level of stress, better sleep, or that it was easier to cope with health problems after using the approach.

Discussion

This report presents the most comprehensive, nationally representative data available describing wellness-related reasons and self-reported perceived health outcomes for adults using complementary health approaches. This research confirms findings from previous studies showing that reasons for using complementary health approaches vary by the type of approach [15]. Additionally, these findings are in line with previous research showing that yoga and natural product supplements are primarily used for wellness-related reasons, while spinal manipulation is more commonly used to treat a specific health problem [8, 9]. The current findings shed light on wellness-related reasons for Americans’ use of these three complementary health approaches and highlight self-reported perceived health outcomes that occur after such use.

The findings indicate some variation in the reasons and self-reported perceived health outcomes for users of different complementary health approaches. For yoga, the most common reasons reported for use included ‘‘general wellness or disease prevention,’’ ‘‘because it focuses on the whole personmind, body and spirit,’’ and ‘‘to improve energy.’’ The current finding that more than 70% of yoga users reported ‘‘because it focuses on the whole personmind, body, and spirit’’ as a reason for practicing yoga is in line with previous research revealing a desire by yoga users for individualized and holistic medical care that does not regard health problems in isolation, but connects the mind and body [16, 17]. The most common self-reported perceived health outcome by yoga users in the current study was a reduction in stress level, which confirms previous research in smaller studies that has found common reasons for using yoga included general wellness, physical exercise, and stress management [8, 17–20].

The most common reason reported for using natural product supplementsgeneral wellness or disease preventionis also consistent with small-scale and qualitative studies [21, 22]. While natural product supplement users were twice as likely to report one or more wellness-related reasons than they were to report treatment of a specific health condition as a reason for taking supplements, specific positive health outcomes were reported at relatively low rates. For example, although 67.5% of natural product supplements users reported that the supplement "improved their overall health and made them feel better," the remaining eight health outcomes were reported by 25% or less of natural product supplement users. This further supports previous findings that natural product supplements are commonly taken for general wellness and prevention of health problems rather than specific outcomes [21].

A 2010 review of scientific evidence on manual therapies found that spinal manipulation may be helpful for a range of conditions including back pain, neck pain, and headaches [23]. Additionally, previous research has demonstrated that individuals report positive experiences and reduced pain as a result of receiving chiropractic care (spinal manipulation), and that a primary reason for using the approach is overall health [24, 25]. The current findings support this prior research by finding that users of spinal manipulation do so to treat a health condition more often than for wellness reasons, and that "improved overall health and made you feel better" was the single most commonly reported reason for or outcome from using spinal manipulation. Additionally, more than one-third of spinal manipulation users reported that this use reduced their stress level, improved their sleep, or helped them cope with health problems.

Previous smaller studies have found associations between the use of complementary approaches and positive health behaviors [26, 27]. The current analyses found that relatively few users of natural product supplements or spinal manipulation reported health behavior outcomes. For instance, less than 25% of each group said they were motivated to exercise more regularly or eat healthier, and less than 7% of these users who were current smokers or drinkers reported being motivated to cut back on these behaviorsand those who did say they were motivated were still drinking or smoking at the time of the interview. However, the findings were more positive for adults who practiced yoga. Nearly two-thirds of yoga users reported that as a result of the approach, they were motivated to exercise more regularly, and 4 in 10 reported that they were motivated to eat healthier. Yoga has previously been shown in clinical trials to be a safe way to improve sleep [28]. Yoga generally is not considered aerobic exercise by practitioners of yoga, but a form of movement meditation and a way to achieve a state of relaxation and balance of mind, body, and spirit [28, 29]. The definition of yoga employed in the current study is consistent with this in that the analysis was limited to individuals who meditated or used breathing exercises as part of their yoga practice.

The current study found that yoga users also perceive high levels of emotional benefits from the practice. More than two-thirds said that yoga made them feel better emotionally or reduced their stress level and made them feel more relaxed. Clinical research has shown that individuals who practice yoga have reduced physiological responses to stress compared with those not using yoga or those new to yoga [30]. Findings related to perceived emotional outcomes were more modest for users of natural product supplements and spinal manipulation. While approximately 40% of spinal manipulation users perceived that the approach reduced their stress or helped them to cope with health problems, only 25% or less of natural product supplement users reported these benefits.

In conclusion, with the exception of immune function, yoga users reported higher rates of all of the wellness-related reasons and perceived health outcomes compared with users of natural product supplements or spinal manipulation. Of note, while differences exist across complementary health approaches, the majority of users of all three approaches perceived that use of a particular complementary health approach improved their overall health and made them feel better. The findings presented here highlight that reasons and self-reported perceived health outcomes vary by the type of complementary health approach used.

Technical Notes

Definitions of selected termsChiropractic manipulation A technique that uses a type of hands-on therapy to adjust problems related to the body’s structure, primarily the spine, and its function.

Natural product supplements Include herbs or other nonvitamin supplements such as pills, capsules, tablets, or liquids that have been labeled as dietary supplements. This category did not include vitamin or mineral supplements, homeopathic treatments, or drinking herbal or green teas.

Osteopathic manipulation A full-body system of hands-on techniques to alleviate pain, restore function, and promote health and wellbeing.

Spinal manipulation Use of either chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation.

Yoga Of Hindu origin, a combination of breathing exercises, meditation, and physical postures, used to achieve a state of relaxation and balance of mind, body, and spirit.

References:

McCaffrey AM, Pugh GF, O’Connor BB.

Understanding patient preference for integrative medical care:

Results from patient focus groups.

J Gen Intern Med 22(11):1500–5. 2007Green AM, Walsh EG, Sirois FM, McCaffrey A.

Perceived benefits of complementary and alternative medicine:

A whole systems research perspective.

Open Complement Med J 1:35–45. 2009Nahin RL, Byrd-Clark D, Stussman BJ, Kalyanaraman N.

Disease severity is associated with the use of complementary medicine to treat

or manage type-2 diabetes: Data from the 2002 and 2007

National Health Interview Survey.

BMC Complement Altern Med 12:193. 2012Lo CB, Desmond RA, Meleth S.

Inclusion of complementary and alternative medicine in U.S. state comprehensive

cancer control plans: Baseline data.

J Cancer Educ 24(4):249–53. 2009Astin JA.

Why patients use alternative medicine: Results of a national study.

JAMA 279(19):1548– 53. 1998Schuster TL, Dobson M, Jauregui M, Blanks RH.

Wellness lifestyles I: A theoretical framework linking wellness,

health lifestyles, and complementary and alternative medicine.

J Altern Complement Med 10(2):349–56. 2004Hawk C, Ndetan H, Evans MW Jr.

Potential role of complementary and alternative health care providers

in chronic disease prevention and health promotion: An analysis of

National Health Interview Survey data.

Prev Med 54(1):18–22. 2012Saper RB, Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Culpepper L, Phillips RS.

Prevalence and patterns of adult yoga use in the United States:

Results of a national survey.

Altern Ther Health Med 10(2):44–9. 2004Davis MA, West AN, Weeks WB, Sirovich BE.

Health behaviors and utilization among users of complementary and

alternative medicine for treatment versus health promotion.

Health Serv Res 46(5):1402–16. 2011Stussman BJ, Bethell CD, Gray C, Nahin RL.

Development of the adult and child complementary medicine questionnaires

fielded on the National Health Interview Survey.

BMC Complement Altern Med 13:328. 2013National Center for Health Statistics

Trends in the Use of Complementary Health Approaches Among Adults:

United States, 2002-2012

National Health Statistics Report 2015 (Feb 10); (78): 1–16National Center for Health Statistics.

2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) public use data release.

NHIS survey description. 2012.

Available from:

ftp:// ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/

2012/srvydesc.pdfParsons VL, Moriarity CL, Jonas K, et al.

Design and estimation for the National Health Interview Survey, 2006–2015.

National Center for Health Statistics.

Vital Health Stat 2(165). 2014.

Available from:

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/ sr_02/sr02_165.pdfRTI International.

SUDAAN (Release 11.0.0) [computer software]. 2012Ernst E, Hung SK.

Great expectations: What do patients using complementary and

alternative medicine hope for?

Patient 4(2):89– 101. 2011Franzel B, Schwiegershausen M, Heusser P, Berger B.

Individualised medicine from the perspectives of patients using

complementary therapies: A meta-ethnography approach.

BMC Complement Altern Med 13:124. 2013Quilty MT, Saper RB, Goldstein R, Khalsa SB.

Yoga in the real world: Perceptions, motivators, barriers, and patterns of use.

Glob Adv Health Med 2(1):44–9. 2013Atkinson NL, Permuth-Levine R.

Benefits, barriers, and cues to action of yoga practice:

A focus group approach.

Am J Health Behav 33(1):3–14. 2009Park CL, Braun T, Siegel T.

Who practices yoga? A systematic review of demographic, health-related,

and psychosocial factors associated with yoga practice.

J Behav Med 38(3):406–71. 2015Chong CS, Tsunaka M, Tsang HW, Chan EP, Cheung WM.

Effects of yoga on stress management in healthy adults: A systematic review.

Altern Ther Health Med 17(1):32–8. 2011Marinac JS, Buchinger CL, Godfrey LA, Wooten JM, Sun C, Willsie SK.

Herbal products and dietary supplements: A survey of use, attitudes,

and knowledge among older adults.

J Am Osteopath Assoc 107(1):13–20. 2007Gardiner P, Kemper KJ, Legedza A, Phillips RS.

Factors associated with herb and dietary supplement use by young adults

in the United States.

BMC Complement Altern Med 7:39. 2007Bronfort G, Haas M, Evans R, Leiniger B, Triano J.

Effectiveness of Manual Therapies: The UK Evidence Report

Chiropractic & Osteopathy 2010 (Feb 25); 18 (1): 3MacPherson H, Newbronner E, Chamberlain R, Hopton A.

Patients' Experiences and Expectations of Chiropractic Care: A National Cross-sectional Survey

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2015 (Jan 16); 23 (1): 3Gaumer G.

Factors Associated With Patient Satisfaction With Chiropractic Care:

Survey and Review of the Literature

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2006 (Jul); 29 (6): 455–462Nahin RL, Dahlhamer JM, Taylor BL, Barnes PM, Stussman BJ, Simile CM, et al.

Health behaviors and risk factors in those who use

complementary and alternative medicine.

BMC Public Health 7:217. 2007Karlik JB, Ladas EJ, Ndao DH, Cheng B, Bao Y, Kelly KM.

Associations between healthy lifestyle behaviors and complementary

and alternative medicine use: Integrated wellness.

J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr (50): 323–9. 2014Yuan CS, Bieber EJ.

Textbook of complementary and alternative medicine.

The Parthenon Publishing Group: New York, NY. 2002Perlmutter L.

The heart and science of yoga.

AMI Publishers: Averill Park, NY. 2005Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Christian L, Preston H, Houts CR,

Malarkey WB, Emery CF, Glaser R.

Stress, inflammation, and yoga practice.

Psychosom Med 72(2):113–21. 2010

Return to MAINTENANCE CARE

Return to ALT-MED/CAM ABSTRACTS

Since 11-15-2015

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |