The Contribution of Musculoskeletal Disorders

in Multimorbidity: Implications for Practice and PolicyThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2017 (Apr); 31 (2): 129–144 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Stephen J.Duffield, Benjamin M.Ellis, Nicola Goodsond. Karen Walker-Bonee, Philip G.Conaghan, Tom Margham, Tracey Loftis

Department of Musculoskeletal Biology,

Institute of Ageing and Chronic Disease,

University of Liverpool, Room 3.42,

Clinical Sciences Centre, University Hospital Aintree,

Liverpool, L9 7AL, UK.

People frequently live for many years with multiple chronic conditions (multimorbidity) that impair health outcomes and are expensive to manage. Multimorbidity has been shown to reduce quality of life and increase mortality. People with multimorbidity also rely more heavily on health and care services and have poorer work outcomes. Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are ubiquitous in multimorbidity because of their high prevalence, shared risk factors, and shared pathogenic processes amongst other long-term conditions. Additionally, these conditions significantly contribute to the total impact of multimorbidity, having been shown to reduce quality of life, increase work disability, and increase treatment burden and healthcare costs. For people living with multimorbidity, MSDs could impair the ability to cope and maintain health and independence, leading to precipitous physical and social decline. Recognition, by health professionals, policymakers, non-profit organisations, and research funders, of the impact of musculoskeletal health in multimorbidity is essential when planning support for people living with multimorbidity.

There is more like this at our

Global Burden of Disease PageKEYWORDS: Arthritis; Back pain; Co-morbidity; Management; Multimorbidity; Musculoskeletal; Osteoarthritis; Osteoporosis; Policy; Prevalence

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

The co-existence of at least two different long-term health conditions in the same individual has been variously defined in the literature as ‘multimorbidity’ or ‘co-morbidity’ but with a lack of clear consensus about the use of these definitions [1]. The term ‘comorbidity’ is generally used for any additional health condition(s) occurring at the same time in the same individual as a previously defined index condition. For the purpose of this review, multimorbidity has been defined as any individual having two or more long-term conditions. For example, a person with concomitant diabetes and asthma has ‘multimorbidity’. Importantly, these terms include long-term mental, as well as physical component health conditions. However defined, there is evidence that the prevalence of people living with two or more long-term health conditions is rising [2].

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) appear to form a principal component of certain multimorbidity clusters [3] and are common in multimorbidity [4], [5]. Certainly, a substantial proportion of people with MSDs now live with multimorbidity [4], [6]. There are many MSDs, including inflammatory rheumatic diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthritis; degenerative conditions, such as osteoarthritis; fragility conditions, such as osteoporosis; and regional pain syndromes, such as low back pain, neck pain and, the widespread pain condition, fibromyalgia. MSDs are common throughout the life course but become increasingly common at older ages (in particular, low back pain and osteoarthritis).

This review sets out what we know about the importance of MSDs in multimorbidity, informed by the work done by the leading UK charity for people with MSDs, Arthritis Research UK [7], and a search of the literature. Our aim is to highlight the importance of multimorbidity and musculoskeletal disease to healthcare commissioners, healthcare providers, government and policymakers, and non-profit organisations to ensure that the complex needs of this growing group of people are appropriately addressed and to inform the research agenda.

The importance of musculoskeletal conditions in multimorbidity

MSDs are markedly heterogeneous, ranging from highly disabling but fortunately less common conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and systemic lupus erythematosus to considerably more common but generally less disabling conditions such as low back pain and osteoarthritis. At older ages, osteoporosis also causes a substantial burden by increasing the risk of low-trauma fractures [8].

In addition, multimorbidity and co-morbidity are defined with inconsistent criteria in the literature. Multimorbidity has been described as having co-occurring long-term conditions; co-occurring long-term conditions or acute conditions; or co-occurring long-term conditions, acute conditions or health-related risk factors [9], [10]. Studies may also use completely different checklists of specific diseases or health-related risk factors. These difficulties with classification cause a particular problem when trying to define the prevalence of multimorbidity [11].

As a consequence, it is also difficult to define the impact of MSDs in multimorbidity. Furthermore, impact can be measured in a number of different ways: on an individual, on an individual's family/carers, society, healthcare resources and costs. Complete data are not available for each of the MSDs in each of these domains, nor indeed for every definition of multimorbidity, making the overall picture patchy. Nevertheless, the following sections outline what we currently know about the relative importance of MSDs in multimorbidity.

Musculoskeletal diseases are a pervasive component of multimorbidity

Multimorbidity can occur for a number of reasons [12]. Chiefly, the existing high prevalence of certain conditions implies that the likelihood of co-occurrence together in one person, by chance alone, is high, particularly for conditions which become more common with increasing age. For example, osteoarthritis and asthma may commonly co-occur but have no known etiological association. Shared risk factors between conditions can also increase the likelihood of clustering. For example, obesity increases the risk of both osteoarthritis and type 2 diabetes [13], [14]. Finally, sometimes a pathogenic link between conditions means the risk of another developing is greater. For example, there is a known causal pathway between rheumatoid arthritis and cardiovascular disease [15]. Below we outline how these three mechanisms of multimorbidity relate to the prevalence of MSDs in multimorbidity.MSDs and multimorbidity are both highly prevalent Longitudinal evidence from various countries suggests that the number of people with multimorbidity is growing [2], [16], [17]. In the European Union, there is an estimated 50 million people with multimorbidity, and this number is expected to grow as the population ages [18]. According to one estimate in England, by 2018, there will be 2.9 million people living with multimorbidity, as compared with 1.9 million in 2008 [2].

Worldwide, prevalence figures for multimorbidity vary greatly depending on the type and the number of conditions included [19], [20]. In UK primary care, 16% of all adults were defined with multimorbidity using a total of 17 conditions then included in Quality and Outcomes Framework (QoF), including asthma, atrial fibrillation, cancer, coronary heart disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive airways disease, dementia, depression, diabetes, epilepsy, heart failure, hypertension, learning disability, mental health problem (psychosis, schizophrenia, or bipolar affective disorder), obesity, stroke and thyroid disease. However, this definition did not include any MSDs and therefore was likely to vastly underestimate the true prevalence of multimorbidity in primary care (QoF has since been updated to include rheumatoid arthritis and osteoporosis). Unsurprisingly, the estimated prevalence increased to 58% when a broader list of long-term conditions was used, which included arthritis, osteoporosis, gout and low back pain [11].

Because of their high prevalence, MSDs have higher odds of co-occurring with other long-term conditions, therefore forming a component disorder in multimorbidity. In the European Union, chronic musculoskeletal pain is experienced by an estimated 100 million people [21]. Back pain, for example, has a mean estimated 1-year prevalence of 38%, worldwide [22]. Across the UK, an estimated 8.75 million people have sought treatment for osteoarthritis, the equivalent to a third of all people over 45 years of age [23]. Additionally, an estimated 1 in 2 women aged over 50 years and 1 in 5 men will sustain a low-trauma fracture as a result of osteoporosis [24], [25], [26], with the situation set to worsen with demographic changes [8]. The endemic high prevalence of these conditions is a key factor in explaining their frequent contribution to multimorbidity.

MSDs and multimorbidity share important risk factors Many important risk factors for common MSDs show striking overlap with risk factors for multimorbidity, even where the definition of multimorbidity has not included MSDs. For example, age and female gender are two of the most important non-modifiable risk factors for MSDs (though this may not be true for individual conditions) [27]. Similarly, there is a greater risk of multimorbidity among women than among men [28], [29]. Unsurprisingly, multimorbidity is also associated with increasing age [11], [28]; the majority of people aged over 65 years are affected by multimorbidity [30]. For example, in Scotland, the estimated prevalence of multimorbidity was 64.9% amongst those aged 65–84 years, and these rates increased to 81.5% among those aged 85 years or over [30].

Modifiable risk factors such as physical inactivity and obesity are importantly associated with osteoarthritis and other regional pain syndromes, including low back pain [13]. Smoking is the main modifiable risk factor for inflammatory arthritis, and lifestyle risk factors for osteoporosis include smoking, poor nutrition and low physical activity [31]. Multimorbidity has a similarly clear association with obesity [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], and while evidence about other modifiable risk factors for multimorbidity is scarce, there are parallels with those for MSDs. For instance, smoking [34], physical activity in elderly males [37] and nutrition [38] have been linked to multimorbidity in recent publications.

Social deprivation has been found to be associated with an increased likelihood of reporting chronic painful conditions, including arthritis and back pain [39]. For example, among English people of working age (45–64 years), the reported prevalence of arthritis was found to be more than double (21.5%) that observed in the least deprived areas (10.6%) [40]. Multimorbidity also shows a strong association with social deprivation [11], [20], [29]; people in the most deprived areas develop multimorbidity on average 10–15 years earlier than those living in the least deprived areas [30]. In particular, a higher risk of multimorbidity including a mental health condition has been demonstrated among people in the most deprived areas (11% versus 5.9%, respectively) [30].

MSDs and long-term conditions may cause and exacerbate one another Lastly, sometimes there are direct causal relationships between MSDs and other long-term conditions. For example, people with rheumatoid arthritis are at increased risk of developing several co-morbid diseases including cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis because of shared aetiological pathways. It has been estimated that one in 20 (6%) people with rheumatoid arthritis develops cardiovascular disease, [41], [42] while osteoporosis is present in three in 10 (30%) [43].

People with poor musculoskeletal health also carry a greater burden of mental health problems. MSDs, like many long-term conditions, are associated with an increased risk of mood, anxiety and substance use disorders. The association is even stronger in those with back pain or fibromyalgia [44], [45]. MSDs and mental health have a complex and reciprocal relationship, each exacerbating, or potentially causing, the other. Living with persistent pain can lead to depression and anxiety. Conversely, psychological distress and depression worsen the experience and reporting of pain [46]. A cycle can therefore develop, with ever-worsening pain and low mood leading to social withdrawal and isolation. People with mental health conditions may also delay seeking treatment, and clinicians may underestimate physical symptoms, attributing these to an individual's mental health condition [47].

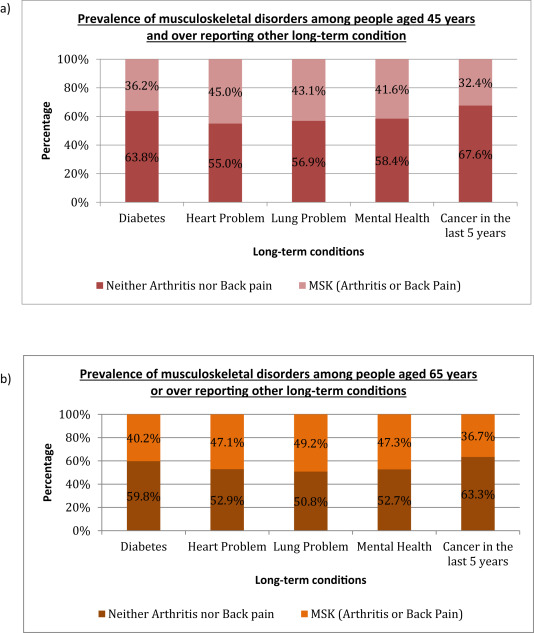

Figure 1 MSDs and multimorbidity frequently occur together A combination of the factors discussed above explains the high prevalence of MSDs found alongside other long-term conditions as part of multimorbidity. For example, it has been shown that among English primary care patients over 45 years of age, reporting living with a major long-term condition, almost a third also have a musculoskeletal condition [40]. Moreover, among those aged >65 years, almost half of those with a heart, lung or mental health problem, also had a MSD (see Figure 1). [40] In the most deprived populations, painful conditions such as osteoarthritis and back pain are the most common multimorbidities among those already living with heart disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or cancer [30].

The converse is also true: people with a MSD have been shown to be more likely to have at least one other long-term condition. For example, according to the results of one study, four out of five people with osteoarthritis had at least one other long-term condition such as hypertension or cardiovascular disease [6].

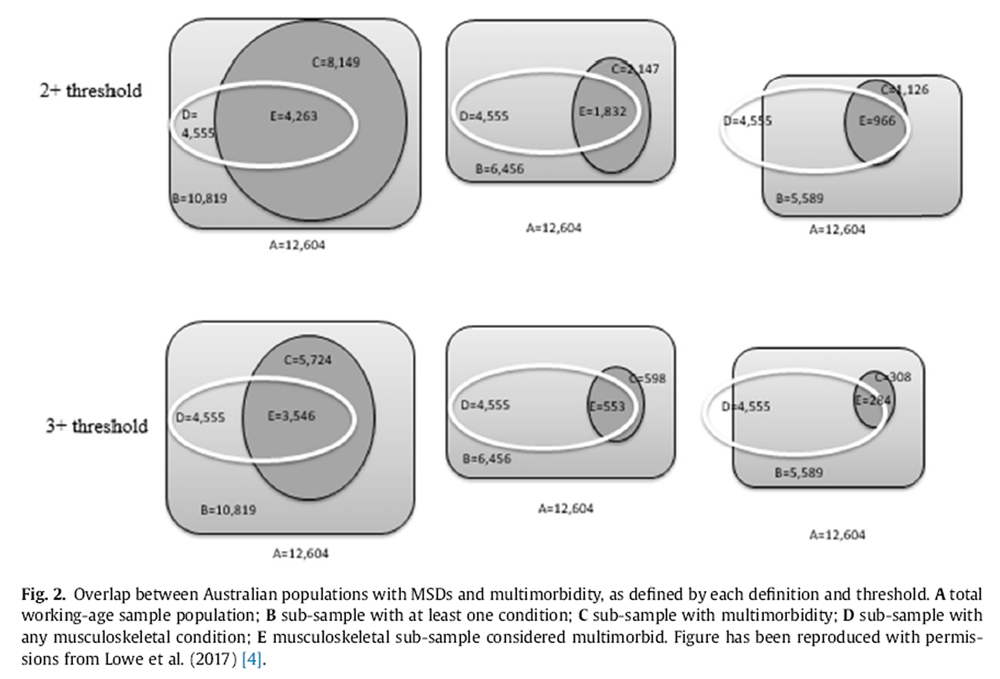

Figure 2 To visualise the relationship between MSDs and multimorbidity and recognise the varying multimorbidity criteria used in the literature, a recent cross-sectional study used three definitions to define the prevalence of multimorbidity in working-age Australians. Two multimorbidity thresholds (i.e. minimum of 2+ or 3+ conditions) and three definitions of multimorbidity from three sources were compared: a survey-based definition from the Australian National Health Survey, a policy-based definition from the Australian National Health Priority Areas and a research definition from a well-cited systematic review. They found that irrespective of how multimorbidity is defined, MSDs are a near-ubiquitous feature of multimorbidity (see Figure 2). [4]

Musculoskeletal diseases exacerbate the impact of multimorbidity

Having seen that MSDs are highly prevalent among people with multimorbidity, it is also important to explore the contribution of MSDs to the total impact of multimorbidity. The personal, societal and economic impact of MSDs and multimorbidity are outlined below.MSDs contribute to the health burden in multimorbidity Worldwide, MSDs are the third largest cause of disability adjusted life years (DALYs) and the largest single cause of years lived with disability (YLD) [48]. Pain is a very common feature of most MSDs. For example, 78% of people with arthritis surveyed by Arthritis Research UK reported that they experience pain most days, with 57% experiencing pain every day [49]. Activities of daily living (ADLs or instrumental ADLs) such as bathing, dressing, getting out of bed or a chair, completing housework, preparing meals and shopping are frequently affected by the pain, along with other common MSD symptoms, such as stiffness, restricted mobility and impaired physical functioning [50]. People often need to make adaptations to their home to enable them to cope. Moreover, symptoms of MSDs, particularly those with an inflammatory cause, tend to fluctuate in severity over time so that their effects are unpredictable [51], [52], [53]. The pain, distress and functional limitations caused by MSDs greatly reduce independence and quality of life and impair an individual's ability to participate in family, social and working life [31]. Arthritis and back pain, in particular, are amongst the most common causes of reduced health-related quality of life in the individual and, because of their high prevalence, the wider population [29], [46]. There is also a significant impact on financial health. Work impairment and increased personal cost mean that 73% of people with severe arthritis struggle with their financial stability relative to their income, as compared with only 6% of those without functional limitations [49].

People with multimorbidity are similarly less able to perform everyday tasks due to functional decline [54]. People with multimorbidity have worsened quality of life and health outcomes than those with one index condition [55]. For instance, in a range of index diseases, the presence of a co-morbidity is consistently shown to increase mortality rates when compared to having the index disease alone [55]. Morbidities tend to accrue in individuals, for instance, as the number of physical co-morbidities increase, so too does the likelihood of developing a mental health problem [30]. This accumulation of pathologies contributes to the complex and numerous needs of people with multimorbidity.

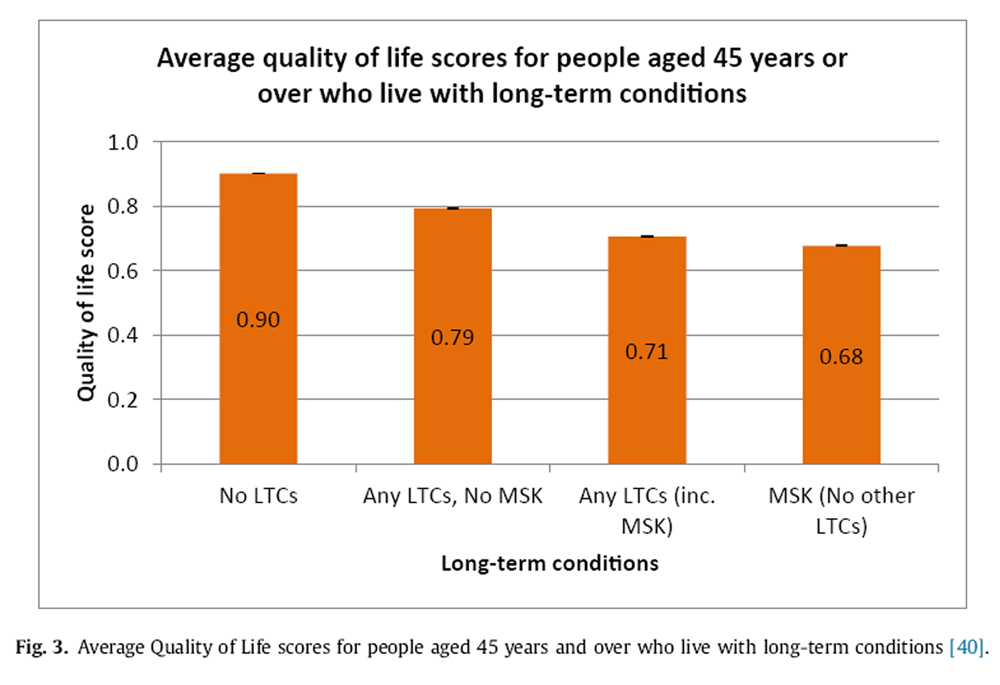

Figure 3 Self-reported Quality of Life (QoL) scores can be used to understand the personal impact of long-term conditions and can help to show the contribution of specific diseases to poor health in multimorbidity. In a national English survey, people living with one or more non-musculoskeletal long-term conditions reported substantially poorer quality of life than those without a long-term condition (QoL score 0.79 vs 0.90, respectively). However, quality of life was even more significantly reduced among those who had arthritis or back pain as part of their multimorbidity (QoL score 0.71). Notably, the impact of the MSDs was significant enough that living with arthritis or back pain resulted in impaired quality of life irrespective of whether arthritis or back pain was the only condition (QoL score 0.68) or was one among multimorbidity (QoL score 0.71) (see Figure 3). This suggests that MSDs disproportionately reduce quality of life in multimorbidity, compared to other long-term conditions [40].

MSDs contribute to the treatment burden in multimorbidity and can impair self-management, leading to health and social decline Despite the proven effectiveness of many individual therapies commonly used in long-term medical conditions, each additional therapy carries a ‘treatment burden’. Treatment burden is a concept that encapsulates the physical effects of treatment, financial losses and the psychosocial effects of time demands and dependence on others for assistance [56]. Quite obviously, the effects of treatment burden increase in a person receiving multiple treatments for multiple health problems. For example, a review of five UK disease-based clinical guidelines concluded that implementation of all individual disease best practice recommendations for a person with multimorbidity would encourage polypharmacy [57]. Recent clinical guidance recommends a person-centred approach to multimorbidity, prioritising treatments that improve quality of life while minimising treatment burden [58].

The existence of any one MSD can contribute significantly to the overall number of treatments a person may be receiving. The management of MSDs aims to improve quality of life by reducing joint pain and stiffness, limiting progression of joint damage, and maintaining or restoring functional ability [59], but achieving this can necessitate the use of a range of interventions. This includes non-drug interventions, e.g. physical activity, heat/cold or physiotherapy. Additionally, drug therapies for MSDs may include topical or oral medication to ease joint pain and stiffness and reduce inflammation. Amongst those severely affected, surgery may be required for people living in constant pain from arthritis, e.g. osteoarthritis is responsible for over 90% of initial hip and knee joint replacements [60], [61].

People with multiple long-term conditions are often required to carry out numerous tasks to maintain their health and administer their healthcare. This includes managing different tablets to be taken at specific times of day, week or only occasionally; keeping stock of their pills, creams, inhalers and injections; requesting repeat prescriptions on time; and visiting the pharmacy to collect items. Monitoring of treatment effectiveness with regular blood tests or physical tests (e.g. blood pressure measurement) may be required, and this may necessitate additional visits to the GP, or to the hospital or may require an additional burden placed upon the individual (e.g. self-monitoring of blood glucose in diabetes mellitus) [56]. As health systems are largely configured to treat individual diseases rather than support those living with multimorbidity [30], managing multiple long-term conditions may require the attention of an array of separate health and care professionals at home, in the community and in hospitals. The time and effort required to remember and attend these appointments (including travel time and car parking or negotiating with hospital transport) contributes to the treatment burden [56].

Having a musculoskeletal condition as part of multimorbidity makes all of these activities more difficult. The Centres for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) Arthritis Program in the USA has identified nine functional limitations that people with arthritis report as being ‘very difficult’ or that they ‘cannot do’, including grasping small objects, lifting or carrying, prolonged sitting or standing, walking a quarter mile, climbing stairs, and stooping, bending or kneeling [62]. As a result, co-morbid arthritis or back pain substantially restricts the function and daily activities of people living with cardiovascular disease, diabetes and respiratory disease [63]. In addition, the unpredictable fluctuations in symptom severity that are a frequent feature of MSDs restrict mobility and can make attending hospital or GP appointments and planning ahead difficult, directly limiting people's ability to manage their health.

The personal expense of MSDs treatment should not be ignored either because these costs may mean that a person with multiple long-term conditions will not be able to afford all their own treatments, leading to deterioration in health. In the United States, osteoarthritis was found to contribute substantially to healthcare insurance expenditures, especially among women. Additional out-of-pocket expenditures were also increased by $1379 per annum in women and $694 per annum in men with osteoarthritis, a substantial personal cost [64]. Nearly half the people with arthritis surveyed by Arthritis Research UK (48%) reported that they could not afford all the treatments they wanted or needed, and this figure increased to nearly 8 out of 10 (78%) among those who stated that they were ‘struggling financially’ [49].

Therefore, for a person who is just managing despite their multiple long-term conditions, developing arthritis can take away their ability to cope with, or afford, treatment. This may prevent effective self-management for other long-term conditions, which could then worsen. For example, people with painful osteoarthritis alongside their other long-term conditions have been shown to have increased risk of needing hospital admission [65]. Therefore, the onset of arthritis may be a ‘tipping point’ for people with multimorbidity, depriving people of their ability to maintain their health and independence, leading to a spiral of decline.

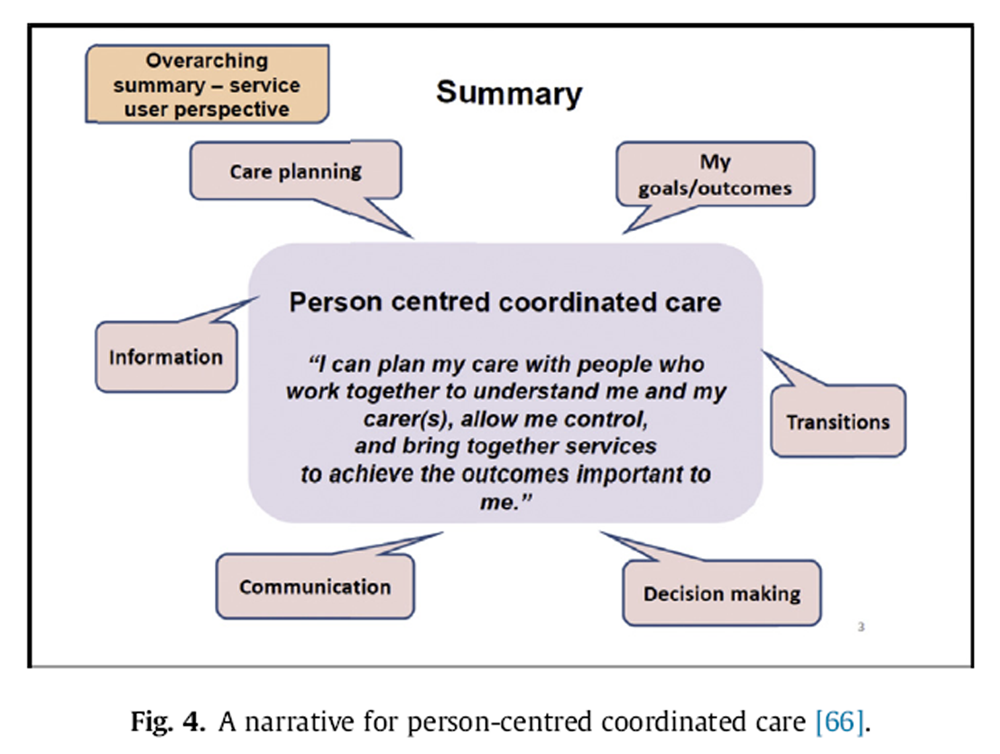

Figure 4

Table 1 MSDs contribute to the impact of multimorbidity on health and care services Management for people with multimorbidity should follow a person-centred, biopsychosocial approach incorporating the six desirable elements of care identified by people with long-term conditions (see Figure 4). [66]. These elements can be enabled through systems to support self-management and shared decision-making and the implementation of care and support planning (see Table 1). However, these systems can be time and resource intensive because of the complexity of the care needed and are increasingly stretched because of the growing number of individuals who need such services. For example, UK health and social care costs average nearly £8000 per year to care for a person living with three or more long-term conditions as compared with an estimated £3000 for a person living with only one long-term condition [2].

The high prevalence and complexity of needs among people with MSDs is likely to contribute heavily to the overall cost of multimorbidity as MSDs carry their own innate burden on health and care services. The Ontario Health Survey, in Canada, found that MSDs were the reason for almost 20% of all healthcare utilisation [67]. In 2015 alone, there were more than 98,211 primary hip replacements and 104,695 primary knee replacements in England and Wales [68]. Across Europe, standardised incidences of hip fractures, requiring emergency surgery, vary but amount to 9 to 11 per 10,000 person-years in the general population [69]. Moreover, because MSDs are usually life-long conditions, people with arthritis may need health and care services for many decades. In England, managing these conditions accounts for the fourth-largest National Health Service (NHS) programme budget of around £5.3 billion annually [70]. In the European Union, it is estimated that 2% of the total annual gross domestic product (GDP) is accounted for by the direct costs of MSDs [71].

In English primary care, people with multimorbidity are frequent users of services [72]: whilst six out of 10 (58%) patients have multimorbidity, they account for almost eight out of 10 (78%) of the consultations in primary care [11]. People with multimorbidity average nine consultations each year compared to four consultations for those without [11]. MSDs contribute importantly to the healthcare burden because one in five of the general population consults their general practitioner (GP) about MSDs annually [73], and MSDs account for one in eight (12%) of all appointments in primary care [74]. Similar estimated rates of consultation have also been reported in other countries, where 10–20% of primary care consultations are for MSDs [75].

The presence of multimorbidity also comes with an increased risk of hospitalisation [76], [77], [78] and hospital outpatient visits [72]. Once in hospital, people being treated for one condition may have other long-term conditions that directly affect their health outcomes. For instance, the presence of co-morbidities increases the 30-day mortality risk of people following hip fracture surgery [79]. Osteoporosis leading to fragility fractures is the major cause of fractures; however, incidence rates of fracture are influenced by fall risk-related co-morbidities such as heart disease, COPD and dementia [80]. Therefore, multimorbidity and MSDs, together, can magnify the total burden in secondary care.

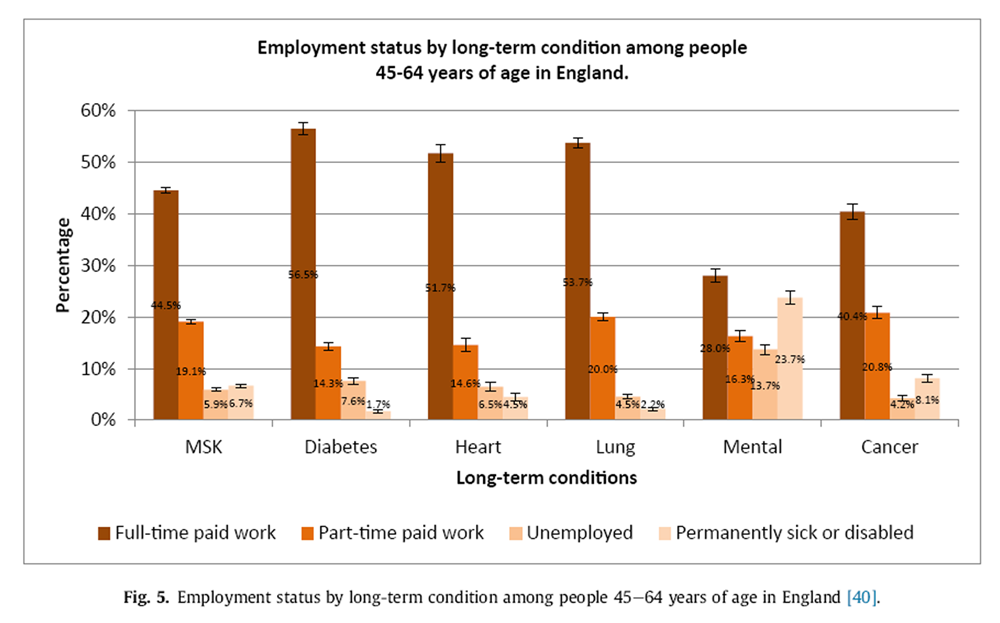

Figure 5 MSDs contribute to the impact of multimorbidity in the workforce and the economy The physical limitations associated with MSDs have a widely acknowledged impact upon work: people with MSDs are less likely to be employed than people in good health and are more likely to retire early [88]. In the European Union and the United States, MSDs are reported to account for a higher proportion of sickness absence from work than any other health condition [21], [89]. In England, people with a MSD have the third lowest rate of full-time paid work (see Figure 5) and are the third highest reported reason for being permanently sick or disabled, after mental health conditions or a recent cancer experience [40]. The indirect costs (inability to work, absenteeism, reduced productivity and informal care) of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis combined have been estimated at £14.8 billion each year [90]. According to another estimate, back pain is responsible for £10 billion of indirect costs to the economy each year [91].

Individually, MSDs and mental health problems are the two biggest causes of the greatest number of working days lost in England [92]. However, these types of conditions frequently occur together. For example, around three in 10 (32%) people of working age who have a musculoskeletal condition also have depression [93]. People with a co-morbid mental health problem alongside a MSD are less likely to be in work than those with musculoskeletal conditions alone [93].

Evidence on the impact of multimorbidity on work outcomes is scarce and often restricted to the study of two specific diseases combined [5]. However, the presence of multimorbidity, and the number of chronic conditions, has been correlated with work absence [94], [95], [96], [97] and reduced work productivity, also known as presenteeism [94], [95]. The impact of multimorbidity on job status and work absence has also been shown to incrementally worsen with each additional condition [5].

Importantly in multimorbidity, it has been shown that the type of long-term conditions, and not only number of long-term conditions, is associated with work outcomes [95]. Therefore, given the recognised effect of MSDs on work, it is likely that these conditions disproportionately contribute to the overall impact of multimorbidity upon work. To illustrate this, one study showed that the effect of multimorbidity upon work disability, sickness leave and job status is significantly amplified when MSDs are included in the definition of multimorbidity [5]. This suggests that MSDs should not be omitted from any studies examining, or adjusting for, the impact of multimorbidity in work participation.

Implications for practice and policy

The Chief Medical Officer for England has acknowledged osteoarthritis as ‘an unrecognised public health priority’ [98]. People with arthritis have also drawn attention to the lack of recognition of their condition within healthcare services and across society [49]. This lack of recognition may be due to a focus on conditions with higher mortality rates rather than those which primarily increase morbidity and reduce quality of life, due to the nihilistic perception that nothing can be done for people with MSDs and that arthritis is an inevitable part of ageing, or due to difficulties measuring musculoskeletal health outcomes because of a lack of biomarkers or simple tests to monitor musculoskeletal health.

Good musculoskeletal health underpins independent living with multiple long-term conditions. It must therefore firstly be recognised and addressed as part of multimorbidity. MSDs negatively impact on quality of life [40], functional ability [63], risk of hospitalisation [65], and work disability [5] in multimorbidity. Metrics and tools developed for multimorbidity management programmes should therefore monitor outcomes that are relevant to musculoskeletal health, including pain and its impact, and functional ability.

We suggest that high-quality data on MSDs and multimorbidity should be routinely obtained, published and used across public health, health and care, and other related systems. These data should identify the scale and needs of people with multimorbidity and support service delivery and quality improvement activities. Currently, routinely collected data sometimes overlooks the co-existence of MSDs, leading to substantial under-estimates of multimorbidity prevalence, let alone their impact.

Local government and public health teams along with healthcare commissioners, payers and providers should identify, segment and understand the needs and requirements of people living with MSDs and multimorbidity in their population. They should identify barriers, including physical barriers, that could limit the access of people with arthritis and MSDs to local programmes. To date, this has been poorly achieved, at least in England, for osteoarthritis and back pain [99].

People with multimorbidity should have access to person-centred, integrated services. For example, care and support planning should be offered to anyone with a long-term condition [100], but particularly to people with multimorbidity [58]. There must be clarity about who will be responsible for carrying out the different actions outlined in a plan, with appropriate support and coordination to link to local services [101]. When supporting people with multimorbidity to identify health goals, professionals should ensure that people have the information they need to make decisions about improving their musculoskeletal health.

Public health information, programmes and campaigns should recognise and address the needs of the growing numbers of people living with multimorbidity and MSDs. The impact of pain and functional limitations on physical activity and independence should be taken into consideration when designing, implementing and evaluating public health information, programmes and campaigns.

Disease-specific non-profit organisations and coalitions should recognise the prevalence of multimorbidity and work together to develop relevant resources, programmes, research and partnerships to meet the changing needs of their beneficiaries. Non-profit organisations should also collaborate with service providers to identify ways of working that meet the needs of people living with multimorbidity, including developing policy, providing information and support, and delivering models of care. In the UK, the non-profit sector is a substantial contributor to health and care support with nearly 36,000 health and social care organisations spending around £4,522 million directly supporting people, health systems or care systems in 2013/14 [102]. This capacity should be harnessed to meet the needs of people with multimorbidity.

Lastly, we suggest that funders must extend support for research to improve understanding of multimorbidity and to develop and evaluate strategies to meet the needs of people with multimorbidity. Organisations that historically have focussed on single disease areas should explore ways to collaborate on multimorbidity research. Facilitation for cross-sector collaborations can come from government-funded research agencies such as the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), which, in 2015, issued a research call for evaluation of interventions or services for older people with multimorbidity [103]. Examples of current multimorbidity research include the 3D study, which is developing and testing a comprehensive ‘3D’ health review every 6 months for people with multimorbidity in general practice [104], and the HEAF study, which is measuring the impact of common health conditions and multimorbidity on work capability and work participation at older age [105].

Summary

MSDs such as arthritis or back pain are common and cause pain, stiffness, reduced mobility and dexterity, and depression. These symptoms affect every aspect of life: family, work and social.

It is now common for people to live with two or more long-term conditions. This multimorbidity reduces quality of life, worsens health outcomes and increases mortality. People with multimorbidity also rely more heavily on health and care services.

People living with multimorbidity often have a MSD as one of their health problems. Living well with multimorbidity involves a litany of complex tasks: monitoring symptoms, managing medications, coordinating carers and attending appointments. The pain and functional limitations associated with arthritis can make taking treatments, getting to appointments and co-ordination of care harder. Therefore, the onset, or worsening, of arthritis or back pain can completely undermine people's ability to cope with their health problems and manage their multimorbidity independently, leading to a precipitous deterioration in health and work-life.

We believe that there is compelling evidence that policymakers, charities and research funders should recognise musculoskeletal health as part of multimorbidity. Consideration and assessment of pain and functional abilities should be included in tools and interventions to identify and support people with multimorbidity. Musculoskeletal health data should be captured and its quality improved; this information should be used in multimorbidity analyses and planning. Healthcare professionals should consider and discuss pain and functional limitations in their care and support planning conversations. Lastly, other professionals and the public should be educated to consider musculoskeletal health as part of multimorbidity through relevant public health resources.

Practice points

Identification: Metrics and tools developed for multimorbidity management programmes should monitor and measure pain and its impact, functional abilities, and capability to manage.

Data collection: National bodies should work together to ensure that data collection, analysis, and publication raises awareness of multimorbidity and the relevance of its musculoskeletal component.

Planning and commissioning: Local planners and commissioners of health and care services should identify, segment and understand the needs and requirements of people living with musculoskeletal disorders and multimorbidity in their populations. This information should be collected and published where possible.

Care and support planning: Health and care professionals should ensure that people with multimorbidity can take part in a care and support planning process. This should use standardised tools to explore and record pain, functional limitations, and how these affect daily activities. Other aspects of patient-centred care, such as shared decision-making, should be an integral part of this process.

Health promotion: Public health organisations should ensure that their information, programmes, and campaigns reflect and address the needs of the growing numbers of people living with multimorbidity including musculoskeletal disorders.

Voluntary sector: Disease-specific non-profit organisations and their respective coalitions should recognise that many people now live with multimorbidity and work together to develop resources, programmes, research, and partnerships. This shared work should aim to meet the changing needs of people with multiple long-term conditions.

Research agenda

Prevalence: Robust surveillance systems should be developed and validated for monitoring multimorbidity prevalence, along with its component diseases, which should include musculoskeletal disorders.

Impact of multimorbidity: More data is needed to define the impact of multimorbidity, and its contributory diseases (including musculoskeletal disorders), on health, healthcare systems, society, and work.

Models and pathways of care: Interventions, systems, and management strategies to support people with multimorbidity to live well should be designed, tested, and scaled up.

Outcome measures: Standardised outcome measures should be developed, validated, implemented, analysed, and interpreted for people with multimorbidity, including musculoskeletal disorders.

Individual perspectives: New research should seek to understand how the attitudes of people and healthcare professionals towards multimorbidity affect health outcomes.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Role of the funding source

SJD is funded by PhD studentship within the ARUK/MRC centre (20665) for MSK health and work. BME and TL are employed by Arthritis Research UK. PGC is supported in part by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), Leeds Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jacqui Oliver for bibliometric support and Einan Snir and Michael Ly for their statistical support.

References:

T.G. Willadsen, A. Bebe, R. Køster-Rasmussen, et al.

The role of diseases, risk factors, and symptoms in the definition of multimorbidity – a systematic review

Scand J Prim Health Care, 8 (August) (2016), pp. 1-10Department of Health Long-term conditions compendium of information (3rd ed.) (2012)

A. Prados-Torres, A. Calderón-Larrañaga, J. Hancco-Saavedra, et al.

Multimorbidity patterns: a systematic review

J Clin Epidemiol, 67 (2014), pp. 254-266D.B. Lowe, M.J. Taylor, S.J. Hill

Cross-sectional examination of musculoskeletal conditions and multimorbidity: influence of different thresholds and definitions on prevalence and association estimates

BMC Res Notes, 10 (1) (2017 Jan 18), p. 51A. van der Zee-Neuen, P. Putrik, S. Ramiro, et al.

Work outcome in persons with musculoskeletal diseases: comparison with other chronic diseases & the role of musculoskeletal diseases in multimorbidity

BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 18 (1) (2017 Jan 10), p. 10F.C. Breedveld

Osteoarthritis–the impact of a serious disease

Rheumatology, 43 (90001) (2004 Feb 1), pp. 4i-8iArthritis Research UK

Musculoskeletal conditions and multimorbidity (2017)P. Mitchell, L. Dolan, O. Sahota, et al.

Osteoporosis in the UK at breaking point

Br Menopause Soc (2010), 10.1353/flm.0.0029J.Y. Le Reste, P. Nabbe, B. Manceau, et al.

The European General Practice Research Network presents a comprehensive definition of multimorbidity in family medicine and long term care, following a systematic review of relevant literature

J Am Med Dir Assoc, 14 (5) (2013 May), pp. 319-325T.G. Willadsen, A. Bebe, R. Køster-Rasmussen, et al.

The role of diseases, risk factors and symptoms in the definition of multimorbidity – a systematic review

Scand J Prim Health Care, 34 (2) (2016 Jun), pp. 112-121C. Salisbury, L. Johnson, S. Purdy, et al.

Epidemiology and impact of multimorbidity in primary care: a retrospective cohort study

Br J Gen Pract, 61 (582) (2011 Jan), pp. e12-e21J.M. Valderas, B. Starfield, B. Sibbald, et al.

Defining comorbidity: implications for understanding health and health services

Ann Fam Med, 7 (2009), pp. 357-363D. Coggon, I. Reading, P. Croft, et al.

Knee osteoarthritis and obesity

Int J Obes, 25 (5) (2001), pp. 622-627W. Yang, J. Lu, J. Weng, et al.

Prevalence of diabetes among men and women in China

N Engl J Med, 362 (12) (2010), pp. 1090-1101C. Meune, E. Touzé, L. Trinquart, Y. Allanore

Trends in cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis over 50 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies

Rheumatology (Oxford), 48 (August) (2009), pp. 1309-1313N.N. Dhalwani, G. O'Donovan, F. Zaccardi, et al.

Long terms trends of multimorbidity and association with physical activity in older English population

Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act, 13 (1) (2016), p. 8S.H. Van Oostrom, R. Gijsen, I. Stirbu, et al.

Time trends in prevalence of chronic diseases and multimorbidity not only due to aging: data from general practices and health surveys

PLoS One, 11 (8) (2016)M. Rijken, V. Struckmann, M. Dyakova, et al.

ICARE4EU: improving care for people with multiple chronic conditions in Europe

Eurohealth Int, 19 (3) (2013), pp. 29-31M. Fortin, M. Stewart, M.-E. Poitras, et al.

A systematic review of prevalence studies on multimorbidity: toward a more uniform methodology

Ann Fam Med, 10 (2) (2012), pp. 142-151C. Violan, Q. Foguet-Boreu, G. Flores-Mateo, et al.

Prevalence, determinants and patterns of multimorbidity in primary care: a systematic review of observational studies

PLoS One, 9 (7) (2014), Article e102149Bevan S, Quadrello T, Mcgee R, et al.

Fit for Work? Musculoskeletal disorders in the european workforce.D. Hoy, C. Bain, G. Williams, et al.

A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain

Arthritis Rheum, 64 (2012), pp. 2028-2037Arthritis Research UK

Osteoarthritis in general practice – data and perspectives, vol. 222, Med Press (2013), pp. 253-258J.A. Kanis, O. Johnell, A. Oden, et al.

Long-term risk of osteoporotic fracture in Malmo

Osteoporos Int, 11 (8) (2000), pp. 669-674L.J. Melton, E.J. Atkinson, M.K. O'Connor, et al.

Bone density and fracture risk in men

J Bone Min Res, 13 (12) (1998), pp. 1915-1923L.J. Melton, E.A. Chrischilles, C. Cooper, et al.

Perspective how many women have osteoporosis?

J Bone Min Res, 7 (9) (1992), pp. 1005-1010R.C. Lawrence, C.G. Helmick, F.C. Arnett, et al.

Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States

Arthritis Rheum, 41 (5) (1998 May), pp. 778-799A. Marengoni, S. Angleman, R. Melis, et al.

Aging with multimorbidity: a systematic review of the literature

Ageing Res Rev, 10 (4) (2011 Sep 30), pp. 430-439R.E. Mujica-Mota, M. Roberts, G. Abel, et al.

Common patterns of morbidity and multi-morbidity and their impact on health-related quality of life: evidence from a national survey

Qual Life Res, 24 (4) (2015 Apr), pp. 909-918K. Barnett, S.W. Mercer, M. Norbury, et al.

Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study

Lancet, 380 (9836) (2012), pp. 37-43P.M. Clark, B.M. Ellis

A public health approach to musculoskeletal health

Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol, 28 (3) (2014), pp. 517-532B. Ahmadi, M. Alimohammadian, M. Yaseri, et al.

Multimorbidity: epidemiology and risk factors in the golestan cohort study, Iran a cross-sectional analysis

Medicine (United States), 95 (7) (2016), Article e2756D.E. Olivares, F.R. Chambi, E.M. Chani, et al.

Risk factors for chronic diseases and multimorbidity in a primary care context of central Argentina: a web-based interactive and cross-sectional study

Int J Environ Res Public Health, 14 (3) (2017)M. Fortin, J. Haggerty, J. Almirall, et al.

Lifestyle factors and multimorbidity: a cross sectional study

BMC Public Health, 14 (1) (2014), p. 686H.P. Booth, A.T. Prevost, M.C. Gulliford

Impact of body mass index on prevalence of multimorbidity in primary care: cohort study

Fam Pract, 31 (1) (2014), pp. 38-43S. de, V. Santos Machado, A.L.R. Valadares, et al.

Aging, obesity, and multimorbidity in women 50 years or older

Menopause J North Am Menopause Soc, 20 (8) (2013), pp. 818-824C.S. Autenrieth, I. Kirchberger, M. Heier, et al.

Physical activity is inversely associated with multimorbidity in elderly men: results from the KORA-Age Augsburg Study

Prev Med (Baltim), 57 (1) (2013), pp. 17-19G. Ruel, Z. Shi, S. Zhen, et al.

Association between nutrition and the evolution of multimorbidity: the importance of fruits and vegetables and whole grain products

Clin Nutr, 33 (3) (2014), pp. 513-520Bridges S.

Chronic pain. [cited 2017 Mar 27].

Available from:

http://content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB09300/HSE2011-Ch9-Chronic-Pain.pdf.Analysis conducted by Arthritis Research UK

GP patient survey (2014)

[Internet], [cited 2017 Mar 27]. Available from:

https://gp-patient.co.uk/S. Norton, G. Koduri, E. Nikiphorou, et al.

A study of baseline prevalence and cumulative incidence of comorbidity and extra-articular manifestations in ra and their impact on outcome

Rheumatology (United Kingdom), 52 (1) (2013), pp. 99-110J.A. Kanis

Osteoporosis III: diagnosis of osteoporosis and assessment of fracture risk

Lancet, 359 (9321) (2002), pp. 1929-1936B. Hauser, P.L. Riches, J.F. Wilson, et al.

Prevalence and clinical prediction of osteoporosis in a contemporary cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatology, 53 (10) (2014 Apr 24), pp. 1759-1766C. Dickens, L. McGowan, D. Clark-Carter, F. Creed

Depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis

Psychosom Med, 64 (1) (2002), pp. 52-60S.B. Patten, J.V.A. Williams, J. Wang

Mental disorders in a population sample with musculoskeletal disorders

BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 7 (2006)S.I. Saarni, T. Härkänen, H. Sintonen, et al.

The impact of 29 chronic conditions on health-related quality of life: a general population survey in Finland using 15D and EQ-5D

Qual Life Res, 15 (8) (2006), pp. 1403-1414Arthritis Research UK

Musculoskeletal health. A public health approach (2014)C.J. Murray, M.A. Richards, J.N. Newton, et al.

UK health performance: findings of the global burden of disease study 2010

Lancet, 381 (9871) (2013 Mar 23), pp. 997-1020ESRO. Revealing Reality

Living well with arthritis: identifying the unmet needs of people with arthritis (2015)

(unpublished)N.A. Spiers, R.J. Matthews, C. Jagger, et al.

Diseases and impairments as risk factors for onset of disability in the older population in England and Wales: findings from the medical research council cognitive function and ageing study

Journals Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci, 60 (2) (2005 Feb 1), pp. 248-254A. Vincent, M.O. Whipple, L.M. Rhudy

Fibromyalgia flares: a qualitative analysis

Pain Med, 17 (3) (2015 Jan)C. Bartholdy, L. Klokker, E. Bandak, et al.

A standardized “Rescue” exercise Program for symptomatic flare-up of knee osteoarthritis: description and safety considerations

J Orthop Sport Phys Ther, 46 (11) (2016 Nov), pp. 942-946P. Suri, K.W. Saunders, M. Von Korff

Prevalence and characteristics of flare-ups of chronic nonspecific back pain in primary care: a telephone survey

Clin J Pain, 28 (7) (2012 Sep), pp. 573-580A. Ryan, E. Wallace, P. O'Hara, S.M. Smith

Multimorbidity and functional decline in community-dwelling adults: a systematic review

Health Qual Life Outcomes, 13 (2015), p. 168R. Gijsen, N. Hoeymans, F.G. Schellevis, et al.

Causes and consequences of comorbidity: a review

J Clin Epidemiol, 54 (7) (2001), pp. 661-674A. Sav, M.A. King, J.A. Whitty, et al.

Burden of treatment for chronic illness: a concept analysis and review of the literature

Health Expect, 18 (3) (2015 Jun), pp. 312-324L.D. Hughes, M.E.T. McMurdo, B. Guthrie

Guidelines for people not for diseases: the challenges of applying UK clinical guidelines to people with multimorbidity

Age Ageing, 42 (1) (2013 Jan 1), pp. 62-69National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management (2016)

NICE guideline NG56W. Zhang, R.W. Moskowitz, G. Nuki, et al.

OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines

Osteoarthr Cartil, 16 (2) (2008 Feb), pp. 137-162R. Pivec, A.J. Johnson, S.C. Mears, M.A. Mont

Hip arthroplasty

The Lancet (2012), pp. 1768-1777D. Ellams, O. Forsyth, A. Mistry, et al.

7 th annual report national joint registry for England and Wales healthcare quality improvement partnership (2010)

[cited 2017 Apr 21]. Available from:

www.njrcentre.org.ukCenters for Disease Control and Prevention’s Arthritis Programme. (2016).

https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/data_statistics/disabilities-limitations.htm.M. Slater, A. Perruccio, E.M. Badley

Musculoskeletal comorbidities in cardiovascular disease, diabetes and respiratory disease: the impact on activity limitations; a representative population-based study

BMC Public Health, 11 (1) (2011 Dec 3), p. 77H. Kotlarz, C.L. Gunnarsson, H. Fang, J.A. Rizzo

Insurer and out-of-pocket costs of osteoarthritis in the US: evidence from national survey data

Arthritis Rheum, 60 (12) (2009), pp. 3546-3553T. Freund, C.U. Kunz, D. Ose, et al.

Patterns of multimorbidity in primary care patients at high risk of future hospitalization

Popul Health Manag, 15 (2) (2012), pp. 119-124National Voices

Narrative for person-centred care (2012)E.M. Badley, I. Rasooly, G.K. Webster

Relative importance of musculoskeletal disorders as a cause of chronic health problems, disability, and health care utilization: findings from the 1990 Ontario Health Survey

J Rheumatol, 21 (3) (1994), pp. 505-514National Joint Registry

Public and patient guide to the National Joint Registry 12th annual report (2015)

[cited 2017 Mar 27]. Available from:

www.njrcentre.org.ukG. Requena, V. Abbing-Karahagopian, C. Huerta, et al.

Incidence rates and trends of hip/femur fractures in five european countries: comparison using E-healthcare records databases

Calcif Tissue Int, 94 (6) (2014 Jun 1), pp. 580-589NHS England » Programme Budgeting.

[Internet], [cited 2017 Mar 27]. Available from:

https://www.england.nhs.uk/resources/resources-for-ccgs/prog-budgeting/.Cammarota A.

The european commission initiative on WRMSDs: recent developments.

Presentation at EUROFOUND conference on “Musculoskeletal disorders”,

Lisbon, October.L.G. Glynn, J.M. Valderas, P. Healy, et al.

The prevalence of multimorbidity in primary care and its effect on health care utilization and cost

Fam Pract, 28 (5) (2011), pp. 516-523What do general practitioners see?

[cited 2017 Mar 27]. Available from:

https://www.keele.ac.uk/media/keeleuniversity/ri/primarycare/bulletins/MusculoskeletalMatters1.pdf.Consultations for selected diagnoses and regional problems the typical general practice

[cited 2017 Mar 27]. Available from:

https://www.keele.ac.uk/media/keeleuniversity/ri/primarycare/bulletins/MusculoskeletalMatters2.pdf.Woolf AD, Pfleger B.

Burden of Major Musculoskeletal Conditions

Bull World Health Organ 2003 (Nov 14); 81: 646–656Canadian Institute for Health Information

Seniors and the health care System?: what is the impact of multiple chronic conditions?

World Health (2011) (January):23 [Internet]. Available from:

https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/air-chronic_disease_aib_en.pdfC. Bähler, C.A. Huber, B. Brüngger, et al.

Multimorbidity, health care utilization and costs in an elderly community-dwelling population: a claims data based observational study

BMC Health Serv Res, 15 (1) (2015 Jan 22), p. 23A. Gruneir, S.E. Bronskill, C.J. Maxwell, et al.

The association between multimorbidity and hospitalization is modified by individual demographics and physician continuity of care: a retrospective cohort study

BMC Health Serv Res, 16 (2016), p. 154Royal College of Physicians

National hip fracture database (NHFD) annual report (2015)T.S.H. Jorgensen, A.H. Hansen, M. Sahlberg, et al.

Falls and comorbidity: the pathway to fractures

Scand J Public Health, 42 (3) (2014), pp. 287-294NICE National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

Patient experience in adult NHS services: (full guidance)

NICE Pathways (2015) [Internet]. Available from:

http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13668/58283/58283.pdfThe King’s Fund

Supporting people to manage their health. An introduction to patient activation (2014)R.L. Kinney, S.C. Lemon, S.D. Person, S.L. Pagoto, J.S. Saczynski

The association between patient activation and medication adherence, hospitalization, and emergency room utilization in patients with chronic illnesses: a systematic review

Patient Educ Couns, 98 (5) (2015), pp. 545-552NHS England.

Shared Decision Making [Internet]. Available from:

https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/pe/sdm/.T. Agoritsas, A.F. Heen, L. Brandt, et al.

Decision aids that really promote shared decision making: the pace quickens

BMJ, 350 (2015) [Internet], [cited 2017 Apr 12]. Available from:

http://www.bmj.com/content/350/bmj.g7624D. Stacey, F. Légaré, N.F. Col, et al.

Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions

Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2014 (2014)A. Coulter

Delivering better services for people with long-term conditions Building the house of care

King’s Fund, London (2013)D.J. Schofield, R.N. Shrestha, R. Percival, et al.

The personal and national costs of lost labour force participation due to arthritis: an economic study

BMC Public Health, 13 (1) (2013 Dec 3), p. 188K. Summers, K. Jinnett, S. Bevan

Musculoskeletal disorders, workforce health and productivity in the United States (2015)Oxford Economics

The economic costs of arthritis for the UK economy (2010)N. Maniadakis, A. Gray

The economic burden of back pain in the UK

Pain, 84 (1) (2000 Jan), pp. 95-103Health and safety executive (2017)

www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/dayslost.htmS. Bevan

Data taken from the work Foundation's analysis of the health survey for England, 2015

Presentation to the symposium (2015)J.J. Collins, C.M. Baase, C.E. Sharda, et al.

The assessment of chronic health conditions on work performance, absence, and total economic impact for employers

J Occup Environ Med, 47 (6) (2005), pp. 547-557R.C. Kessler, P.E. Greenberg, K.D. Mickelson, et al.

The effects of chronic medical conditions on work loss and work cutback

J Occup Environ Med, 43 (3) (2001), pp. 218-225M. Ubalde-Lopez, G.L. Delclos, F.G. Benavides, et al.

Measuring multimorbidity in a working population: the effect on incident sickness absence

Int Arch Occup Environ Health, 89 (4) (2016), pp. 667-678M.A. Buist-Bouwman, R. De Graaf, W.A.M. Vollebergh, J. Ormel

Comorbidity of physical and mental disorders and the effect on work-loss days

Acta Psychiatr Scand, 111 (6) (2005), pp. 436-443Department of Health

Annual report of the Chief Medical Officer. On the state of the public's health

(2012)Arthritis Research UK

A fair assessment? Musculoskeletal conditions: the need for local prioritisation (2015)J. Burt, J. Rick, T. Blakeman, et al.

Care plans and care planning in long-term conditions: a conceptual model

Prim Health Care Res Dev, 15 (4) (2014 Oct), pp. 342-354(2016).

www.ageuk.org.uk/professional-resources-home/services-and-practice/integrated-care/integrated-care-model/NCVO

Almanac 2016

https://data.ncvo.org.uk/a/almanac16/scope-5/National Institute for Health Research

Multimorbidities in older people themed call (2015)M.S. Man, K. Chaplin, C. Mann, et al.

Improving the management of multimorbidity in general practice: protocol of a cluster randomised controlled trial (The 3D Study) BMJ Open, 6 (2016)

p. no pagination-no pagination. [Internet]. Available from:

http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/6/4/e011261.full.pdf+html%5Cn

http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed14&NEWS=N&AN=20160399047K.T. Palmer, K. Walker-Bone, E.C. Harris, et al.

Health and Employment after Fifty (HEAF): a new prospective cohort study

BMC Public Health, 15 (1) (2015 Dec 19), p. 1071

Return to GLOBAL BURDEN OF DISEASE

Since 12-22-2018

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |