A Comparison of Quality and Satisfaction Experiences

of Patients Attending Chiropractic and

Physician Offices in OntarioThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Can Chiropr Assoc 2014 (Mar); 58 (1): 24–38 ~ FULL TEXT

Edward R Crowther

Associate Professor, Division of Chiropractic,

School of Health and Medicine,

International Medical University,

No. 126 Jalan Jalil Perkasa 19,

Bukit Jalil, 57000 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Introduction: Improving the quality of healthcare is a common goal of consumers, providers, payer groups, and governments. There is evidence that patient satisfaction influences the perceptions of the quality of care received.

Methods: This exploratory, qualitative study described and analyzed, the similarities and differences in satisfaction and dissatisfaction experiences of patients attending physicians (social justice) and chiropractors (market justice) for healthcare services in Niagara Region, Ontario. Using inductive content analysis the satisfaction and dissatisfaction experiences were themed to develop groups, categories, and sub-categories of quality judgments of care experiences.

Results: Study participants experienced both satisfying and dissatisfying critical incidents in the areas of standards of practice, professional and practice attributes, time management, and treatment outcomes. Cost was not a marked source of satisfaction or dissatisfaction.

Conclusion: Patients may be more capable of generating quality judgments on the technical aspects of medical and chiropractic care, particularly treatment outcomes and standards of practice, than previously thought.

Keywords: chiropractic care; quality; satisfaction.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

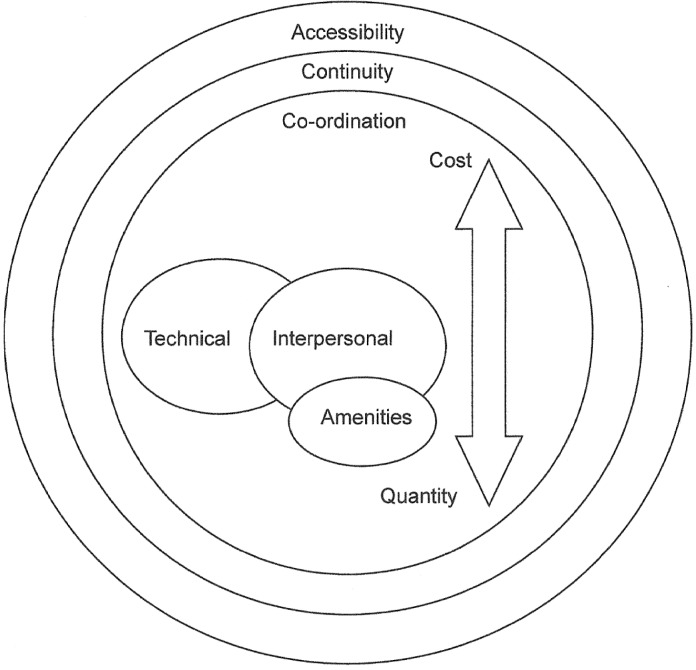

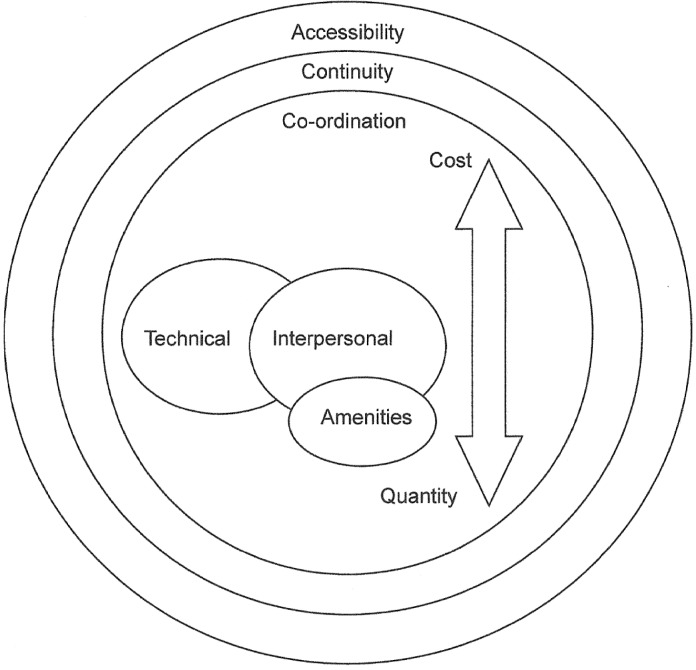

Much of our conceptualization of healthcare quality has come from the work of Donabedian. [1] Published in 1980, Donabedian’s Explorations in Quality Assessment and Monitoring brought together broad acknowledgements of early notions of healthcare quality. These included safety, accessibility, coordination of service delivery within and across systems, interpersonal skills of health professionals, the technical abilities of health services providers, and cost. From these Donabedian developed a Unifying Model of Quality that defined healthcare as the management by a practitioner of a clearly definable episode of illness in a patient.

This management, or “module of care” is characterized by three components;technical care, or the application of science and technology of healthcare to an episode of illness;

the social and psychological management of the patient and;

amenities, those things that contribute to the comfort, promptness, courtesy, privacy and acceptability of healthcare.

Figure 1 Donabedian expanded his Unifying Model to include other components. While insufficient quantity of healthcare services is a well-recognized concern, excess care delivery that provides no benefit or increases the risk of harm, is associated with poor quality. Cost remains inextricably linked to quantity; as costs increase, the quantity of healthcare services decrease. Conversely, low-cost, or free healthcare services increase utilization and risk of harm from care that is useless or precludes the delivery of effective care. Three activities of healthcare delivery are considered to be linked to quality. Accessibility is achieved when care is easy to initiate and maintain. Financial, spatial, social and psychological factors contribute to the ease or difficulty in accessing care. Effective coordination of care is achieved when there remain no interruptions in the delivery of successive modules of care within and across health disciplines and health systems. Continuity is achieved with preservation of the orderly and reasonable evolution of care. Figure 1 considers the components and relationship of Donabedian’s Unifying Model of Quality.

While Donabedian considered healthcare quality to be “whatever you want it to be” he considered that the patient was solely responsible for rating the attributes of quality of care. [2] The collective summation and balancing of these attributes of care is considered patient satisfaction and is a reflection of the quality of care delivered. Satisfaction and quality are inextricably linked and interchangeable.

Donabedian’s Unifying Model has formed the basis for the development of a number of quality improvement initiatives in healthcare. In the United States, the Committee on the Quality of Health Care in America generated six aims for improvement in health services; safety, effectiveness, patient-centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, and equity. [3] In Canada, the “Romanow Report” considered threats to health care delivery including accessibility, coordination, cost and quality. [4] The concepts of quality in medicine and population health occupy a significant portion of the literature on healthcare quality.

This is not the case in chiropractic. There remains a paucity of research exploring the chiropractic patient’s concept of quality. A number of studies of have considered satisfaction with chiropractic and medical care in diagnostic related conditions such as low back pain [5-8], asthma [9], and management of their conditions in general. [10] Quantitative satisfaction studies suggest that patients are satisfied with the interpersonal and psychosocial management of their problems through concern for their condition, advice for self-management, explanation of treatment and accessibility to care. They were least satisfied with cost.

The direct comparison of quality in the delivery of medical and chiropractic services in Canada is difficult. The delivery of medical care in Canada occurs within a social justice context where access to basic medical care is considered a right. [11] As there is no limit to healthcare service consumption when cost is removed government “planned rationing” limits access to services. This rationing is consistent with current complaints with the Canadian healthcare system concerning access to a diagnostic services and interventions. [4] Conversely, chiropractic services are generally delivered in Canada within a market justice system. Subject to the laws of supply and demand, equilibrium is achieved when the capacity to pay for chiropractic services meets the ability of chiropractors to provide those services at a price.

In Ontario, both professions have been impacted in their ability to provide high quality care. For medicine this includes a lack of investment by governments in health care infrastructure and training sufficient number of physicians. [12, 13] For chiropractors it has been a chronic overproduction of chiropractors for the marketplace, decreased utilization of chiropractic services and competition from other allied health professions. [14]

Against this contrasting backdrop of social and market justice delivery of medical and chiropractic services in Ontario, and within the theoretical framework of Donabedian’s Unifying Model of Quality, this exploratory, qualitative study describes and analyzes the similarities and differences in satisfaction and dissatisfaction experiences of patients attending primary care physicians (social justice) and chiropractors (market justice) for healthcare services in Niagara Region, Ontario.

Using inductive content analysis the satisfaction and dissatisfaction experiences are themed to develop groups and categories of quality judgments of care experiences of patients. These groups and categories are considered in the light of Donabedian’s framework of technical skill, interpersonal skills, amenities, cost, accessibility, continuity and coordination.

Methods

Selection and Description of Participants

Recruitment of patient study participants and data collection took place in 20 chiropractic offices in the Region of Niagara, Ontario. To insure the greatest exposure to potential study participants, only practitioners in full-time practice (greater than 15 hours per week) and who treated in excess of 35 patients per week for greater than five years were invited to participate. [15]

Potential chiropractors were selected from the College of Chiropractors of Ontario Search Option webpage by location. [16] The CCO database yielded 152 chiropractors registered in the Niagara Region. Of these, 43 were not considered eligible for the study for a variety of reasons including suspensions, revoked licenses, resignations, active but non-practicing status, and inactive and deceased status. Fourteen chiropractors were considered to be ineligible due to potential conflict of interest with the researcher (ERC). Seventeen of the chiropractors were not eligible for inclusion as they had been in practice less than five years. Of the remaining 92 practitioners, 18 agreed to participate in the study. Two additional chiropractors were recruited from the adjacent Hamilton Region to participate in the study.

Population and Sample

Women and men aged 21 or older attending for chiropractic treatment at one of the 20 participating chiropractic offices were asked to participate in the study. No interviews were conducted at primary care physician offices.

The sample was a convenience sample of 200 patients attending for chiropractic treatment. Inclusion criteria required subjects to be aged 21 years or older; attended both a chiropractor and a family physician at least twice in the preceding year for examination or treatment and; consented to participate in the study.

Data Collection Methods

Patients who met the inclusion criteria and wished to participate in the study were given a Consent Form to review and sign. To avoid congestion and time delays in the daily flow of care delivery and impact perceptions of satisfaction, the remainder of data collection took place prior to or following the delivery of the chiropractic treatment. Basic demographic data was collected including age, gender, number of years as a chiropractic patient with most current practitioner, number of years as a medical patient with most current physician, and total average, annual out-of-pocket cost estimates for both chiropractic and medical visits.

The researcher (ERC) conducted a brief interview with each study participant using Flanagan’s Critical Incident Technique. [17] Widely used in business, education, military and healthcare settings, Critical Incident Technique (CIT) and related criteria is a systematic, inductive, open-ended procedure for eliciting verbal or written information from respondents. [18, 19] An incident is any observable human activity that is sufficiently complete to permit inferences and predictions to be made.

A critical incident must satisfy five criteria:is the actual incident reported;

was it observed by the reporter (study participant);

were all relevant factors in the situation given;

has the reporter (study participant) made a definite judgment regarding the criticalness of the incident and;

has the reporter (study participant) made it clear just why she or he believes the incident was critical?Criteria One through Three address the validity of the experience. The remaining two criteria identify observed behavior that was significant and meaningful to the aim of the activity under study, and to generate explicit reasons for those judgments.

Five pre-determined, adapted, semi-structured questions were posed to each participant;think of a time when, as a chiropractic/physician patient, you had a satisfying/dissatisfying care experience;

when did the incident happen;

exactly what happened;

what specific circumstances led up to this care experience and;

what resulted that made you feel that the care experience was satisfying/dissatisfying? [20]This was repeated until the study participant was interviewed concerning a satisfying chiropractic care experience, dissatisfying chiropractic care experience, a satisfying medical care experience, and a dissatisfying medical care experience. The interviews were digitally recorded for transcription and content analysis. To standardize and facilitate all aspects of the data collection and analysis processes, twenty test interviews were conducted, recorded, transcribed and reviewed prior to the experimental maneuverer.

Human Rights Protection

Full Institutional Review Board approval was received. This study employed methodology to insure the confidentiality of study participants and the anonymity of their data but allow for withdrawal from the study up to 72 hours after participation. To insure study participant privacy and confidentiality all interviews were conducted in a private setting within the chiropractic offices.

Treatment of Data

Recorded and transcribed interviews of study participants were reviewed and consensus achieved by two separate reviewers against the criteria to determine if the experiences were Critical Incidents. [17] A third reviewer (ERC) resolved disagreements between reviewers. Interviews considered not to be critical incidents were excluded from further analysis.

This study employed inductive content analysis as developed by Strauss. [21] Interviews of satisfying and dissatisfying experiences of patients attending physicians and chiropractors were grouped separately for content analysis. The data was reviewed through careful and repeated readings to identify dimensions or themes that were meaningful to the study participants. Further reading and analysis lead to a sorting of themes and dimensions into major groups. Successive clustering processes were conducted until categories and sub-categories within groups were identified.

A label that articulated and broadly defined the satisfying and dissatisfying groups, categories, and sub-categories was generated. To confirm label validity, each reviewer involved in the earlier consensus was asked to sort thirty incidents according to groups and category labels. Inter-rater agreement between the reviewers and the researcher was calculated. Validity was established at 80%.

Descriptive statistics were used to calculate means and percentages to describe the study group and the differences in out-of-pocket costs and years of attendance at chiropractors and physicians. The n’s of each domain, group, category, and sub-category were analyzed using descriptive statistics to describe the differences between the two groups. The qualitative differences between the chiropractors and physician domains, groups, categories and sub-categories were explored.

A relative strength of differences scale was created to more effectively describe the levels of differences between the percentages and n’s of the groups within the Satisfying and Dissatisfying Domains, Groups, Categories and Sub-categories.

It consisted of four relative strength levels;0 – 4% difference represented no differences between groups;

5 – 9% difference represented minimal differences between groups;

10 – 14% difference represented moderate differences between groups and;

15% or greater difference represented marked differences between groups.

Results

Study Group Description

In all, 197 participants were recruited from 20 participating chiropractors. Of these 62% (n=122) were female; 38% (n = 75) were male. The mean age of the study participants was 55.0 years (SD + 16.1). Study participants, on average, had been patients of their family physicians for 15. 4 years (SD = 11.4), compared to 10.3 years (SD = 9.1) for their chiropractors. When study participants attended their family physicians they did so, on average, 3.9 (SD = 2.8) times per year. This is significantly lower than the attendance at their chiropractors. On average, study participants attended their chiropractor 20.9 (SD = 19.4) times per year.

The mean annual cost for all study participants attending chiropractors was $355.70 (SD = $310.48). Sixty study participants incurred no costs for chiropractic services as visits were fully covered by a variety of insurers. Ten study participants incurred annual costs ranging from $20 to $120 at their physician’s for services charges.

Domain Development

In all, 197 study participants participated in the study providing for 394 satisfying interviews. Ten interviews were excluded as they did not meet the criteria for a satisfying critical incident: five each for satisfying physician and satisfying chiropractic. The total n of the Satisfying Domain was reduced to 384, or 192 for each of the satisfying physician and satisfying chiropractic. There were 394 dissatisfying interviews in total. Ten interviews were excluded having not met the criteria for a dissatisfying critical incident: five each for dissatisfying physician and dissatisfying chiropractic. The total n of the Dissatisfying Domain was reduced to 384, or 192 for each of the dissatisfying physician and dissatisfying chiropractic. The collection of satisfying and dissatisfying critical incidents were termed “domains”, a reflection of the highest taxonomic level.

Group Development Within The Satisfying and Dissatisfying Domains

Each critical incident transcript was reviewed using inductive content analysis. Six distinct, identical groups became clear within each of the Satisfying and Dissatisfying Domains.

For the Satisfying Domain these includedSatisfying Time Management,

Satisfying Treatment Outcomes,

Satisfying Standards of Practice,

Satisfying Professional and Practice Attributes,

Satisfying Cost, and

Satisfying Gestalt Experiences.For the Dissatisfying Domain, this included

Dissatisfying Time Management,

Dissatisfying Treatment Outcomes,

Dissatisfying Standards of Practice,

Dissatisfying Professional and Practice Attributes,

Dissatisfying Cost, and

Dissatisfying Gestalt Experiences.A number of interviews were gestalt in nature. Study participants had a general sense of whether they were satisfied, or dissatisfied, with their health care professional based on overall, general actions of their practitioners on every visit.

Category Development Within Satisfying Groups

Table 1

Table 2

Table 3

Table 4 page 8 Within the Satisfying Domain, each Group was further reviewed to identify discrete categories. The satisfying groups, categories, labels and descriptions are found in Table 1.

The frequency and percentages of the n’s of the Satisfying Groups and Categories and the relative strengths of differences are found in Table 2.

Category Development Within Dissatisfying Groups

Within the Dissatisfying Domain, each Group underwent further content analysis into categories. In some instances these categories were similar to categories found within groups in the Satisfying Domain Groups. In some instances additional, new categories emerged within each group not present in Satisfying Domain Groups. The Dissatisfying groups, categories, subcategories, labels and descriptions are found in Table 3.

The frequency, percentages and relative strengths of the Dissatisfying Groups, Categories and Sub-categories are found in Table 4.

The validity of category labeling was challenged. Each of the two reviewers involved in the inclusion and exclusion of the interviews was asked to sort a series of critical incident interviews according to category, and sub-category labels. Thirty satisfying critical incident transcriptions (15 physician, 15 chiropractic) and thirty dissatisfying critical incident transcriptions (15 physician, 15 chiropractic) were allocated to Reviewer Number One and Number Two. Reviewer Number One correctly allocated 86% (n = 26) of the critical incidents to their respective categories and sub-categories. Reviewer Number Two completed a similar task correctly allocating 83% (n = 25) of the critical incidents to their respective categories and sub-categories. A pre-determined level of acceptability was considered to be 80%.

Calculations of Relative Strengths of Differences

The relative strength of differences between n’s of physician and chiropractic satisfying and dissatisfying categories, groups and sub-groups was calculated using four relative strength levels as outlined in the methods. Results are highlighted in Table 2 and Table 4.

Discussion

The study participants in this research roughly mirror that which is known about utilization of chiropractic services in Ontario. This study population consisted of 62% female and 38% male in keeping with increased utilization among female patients. The mean age was 55.0 years (SD = 16.1) and consistent with utilization by older individuals. Large differences were seen in annual utilization. Study participants attended their physicians on average 3.9 (SD = 2.8) but their chiropractors 20.9 (SD = 19.4). This likely represents the nature of chiropractic practice where patients are often managed for chronic conditions and for supportive and wellness care.

In a market justice system cost is expected to be a significant constraint in utilization. Interestingly 60 participants incurred no costs associated with attending their chiropractors having expenses covered by insurance carriers or other agencies. The remainder paid, on average, anywhere from $200 to greater than $1,800 annually. Half of the study participants paid less than $200 annually. Cost was considered by only three study participants to be dissatisfying. One participant voiced concern that the fees charged by their chiropractor were not consistent with the level of training required to become a chiropractor and therefore undervalued. For physicians, where the assumption a social market would keep fees hidden, ten participants cited paying between $20 and $120 for “administrative fees” to cover future requests such as sick leave notes, form completion and file management. No participant cited the “free” cost of health care as a satisfying incident for either chiropractic or medical services. Within the chiropractic experience a mixed model existed with participants having complete, partial or no coverage for costs. For some attending physicians unexpected out of pocket costs did occur.

When the satisfying critical incidents underwent inductive analysis a number of categories emerged. These included standards of practice, satisfying time management, treatment outcomes, satisfying professional and practice attributes, satisfying gestalt experiences and cost. Not surprisingly, the corollary is that the dissatisfying incidents would mirror the categories from satisfying domain. Indeed that was the case where critical incidents were themed around the similar categories of standards of practice, satisfying time management, treatment outcomes, satisfying professional and practice attributes, satisfying gestalt experiences and cost. It is clear that study participants experienced both similar satisfying and dissatisfying experiences at both their physician and chiropractors around time management, professional and practice attributes, treatment outcomes, standards of practice, gestalt experiences, and in some cases cost.

When applying Donabedian’s framework on the quality of care that includes technical care, interpersonal care amenities, cost, quantity, continuity and coordination a number of observations are made.

Technical Component of Care Quality

Considering first the technical component of a module of care, the most prominent judgment on care quality is treatment outcomes. Almost exclusively, and overwhelmingly, study participants considered high quality chiropractic care to include either a full resolution of their complaints (marked difference) or a positive response to treatment (marked difference). Poor quality care was a result of protracted recovery times (marked differences), aggravation of presenting complaints (marked difference), care that provided no benefit (minimal difference), or carried with it other iatrogenic side effects.

Almost absent among study participants was any judgment on high quality treatment outcomes from their physicians. In their absence, however, were a number of poor quality judgments of physicians when they had no or incorrect treatment available (moderate difference). It may not be unreasonable to suggest that, for the most part, study participants have little expectation of their family physicians to address their immediate health concerns in a positive or negative way from treatment they are likely to deliver. The opposite for chiropractic practitioners is clear. Patients expect high quality intervention delivery and are unsatisfied when treatment fails to meet their expectations. In the context of Donabedian’s framework, where care should maximize benefit and minimize risk, the study participant responses are surprising. Almost half of the satisfying experiences related to a reduction or resolution of symptoms while half of the dissatisfying experiences are related to a failure to respond or resolve symptoms, an exacerbation of presenting complaint or new iatrogenic complaints. Indeed, when it comes to chiropractic care study participants appear to have a more acute awareness of the quality of the technical components of care in ameliorating or aggravating their pain-related conditions.

The second group that is firmly anchored in the technical component of care is Standards of Practice. Comprised of the key competencies of professional practice including ability to diagnosis, communicate a diagnosis, provide treatment options, initiate timely and appropriate referrals, maintain appropriate records, it is dominated by both high quality and poor quality judgments of care delivered by physicians and, less so by chiropractors. When high quality judgments are awarded for physician care in this group, it is primarily for the ability of the physician to generate a diagnosis (marked difference) and to make timely and appropriate referrals (marked difference). When poor quality judgments are offered they are overwhelmingly for physicians in every category including delayed diagnosis (minimal difference), failure to diagnosis (marked difference), generating incorrect diagnoses (marked difference), failing to refer (marked difference), and keeping inadequate records (moderate difference). Study participants clearly expect a high degree of competence in their physician to establish a diagnosis and make a timely and appropriate referral. They provide poor quality judgments when they fail to generate an accurate diagnosis in reasonable time, fail to refer, and fail to keep adequate records.

For chiropractors, high quality judgments are awarded for variety in treatment options (minimal difference) and ability to manage multiple health concerns (minimal difference). Few study participants provided poor quality judgments for failure to diagnosis, make timely and appropriate referrals, and keeping adequate records for chiropractic experiences. It might appear that study participants see a greater responsibility of their physicians to diagnose, refer, and keep adequate records. Chiropractors, trained and regulated to be primary contact practitioners, are required to adhere to similar standards of practice activities as physicians in the areas of diagnosis, referral, and record keeping. This tends not to be a source of satisfaction and dissatisfaction and of expectation of study participants vis-à-vis their chiropractors.

Considering both the Treatment Outcomes and Standards of Practice Groups within the technical components of care a number of things becomes clearer. Donabedian considered that by and large overall judgments of care quality were based on a patient’s perception of quality of care from the interpersonal and amenities domains. He considered that few patients had the capacity to rate the technical quality of care. For physician judgments in this study, participants were most satisfied with aspects of diagnosis and a referral to another provider for additional assessment and treatment. They were dissatisfied when, in their view, these expectations were not met. For quality judgments concerning chiropractic care, in general, study participants were keenly aware of the success or failure of the interventions. As pain appeared to be the primary outcome, study participants were provided with a convenient benchmark to assess the high quality, or poor quality of treatment outcomes. Combined, these quality judgments represent almost 50% of all critical incidents reported in this study. There is some suggestion that patients may make significantly more quality judgments concerning technical quality than originally considered by Donabedian.

Interpersonal Component of Care Quality

The second component of Donabedian’s framework considered the interpersonal aspects of care. Most quality judgments in this study are found in the Professional and Practice Attributes. Once again, the overall frequencies of responses are primarily physician in nature. From an interpersonal perspective, study participants generated more high quality judgments in the area of professional attributes (moderate difference) for their physicians. They were more likely, and often, to describe their physician as caring, compassionate, competent, kind, ethical, and available than their chiropractor (marked difference). By virtue of scope of practice physicians are more likely able to engage in heroic, life saving acts (minimal differences). When study participants confirmed poor quality judgments on their physicians it was on descriptions of professional attributes such as miserable, disagreeable, reluctant, drug pusher, disrespectful, disinterested, and a failure to advocate on their behalf (no difference).

They expect their physicians to portray the requisite professional attributes and interpersonal skills and are dissatisfied when they fail to meet their quality expectations. With the exception of some interest in high quality judgments around personal attributes such as kindness, compassionate, and dedicated quality judgments, attributes to chiropractors in this component of care are limited. Paradoxically study participants are more likely to raise concerns over professional attributes of chiropractors describing them as lacking initiative, providing therapies of convenience to the chiropractor, intellectually condescending, prone to over treatment and overbilling and having ethical conflicts of interest around marketing and sales (no difference).

Amenities Component of Care Quality

The third component of a module of care is amenities. Such amenities as warm and welcoming office environments were proposed for both chiropractors and physician office environments but these were limited. Chiropractors were most likely to garner poor quality judgments on amenities with concerns over décor, climate control, and lack of simple office conveniences such as coat racks (no difference).

Cost

Cost and quantity are considered to be inter-related. Cost as a factor influencing quality of care was almost a non-factor in this study. Few study participants had any quality judgments to pass on cost. Most surprisingly, few quality judgments were passed on cost and chiropractic services. While 25% of study participants incurred no personal costs associated with their consumption of chiropractic services, the remainder paid, on average $350.00 annually for care. No study participant considered that the cost of chiropractic care was economically burdensome. There were however some other indicators of cost, supply and quality. Seven study participants considered that simply having their physician accept them as a patient was a high quality judgment. This might be considered a reflection of a system that has trained too few physicians for the population. It might also simply, and most probably, reflect a local variation is physician supply.

Although cost did not appear to represent a significant barrier to access to care for the chiropractic group this is reported with limitations given that this study, by its nature, sampled those study participants with the financial capacity to attend for chiropractic care. No study participant voiced that the quality of their chiropractic care was compromised by cost and the ability to attend as frequently as they wished. Cost for care for physicians, naturally, within a social justice system, was not a source of poor quality judgments.

Accessibility, Continuity, Coordination

Overlapping the three components of technical, interpersonal, amenities and cost are accessibility, continuity, and coordination. Care is considered to be accessible when it is easy to initiate, and maintain with limited financial, spatial, social, and psychological factors are factors that enhance or detract from accessibility. For chiropractors, a number of poor quality judgments were cited around what might be considered to be physical access to care. This included a lack of disability access ramps and doorways, poor office maintenance, and snow removal. Outside of parking issues, physical access was not a quality issue for physicians. Physicians were most likely to be plagued with poor quality judgments over access to their HCP of Choice. Given the emergence of Family Health Teams that, by design, recruit other health professionals such as nurse practitioners, it is more likely that study participants might encounter a circumstance where the physician may not see them. This is compounded by a medical training system that places clerks and residents in the family physician and family health team offices. While it may not be unreasonable to think that study participants might be buoyed with the notion of their physician being involved in medical education, no study participant considered that this enhanced the quality of their experiences. This is less likely to occur in the chiropractic realm. Only two chiropractic study sites incorporated other health professionals. These two sites were the principle source of dissatisfaction where study participants were treated by physiotherapists or, on occasion, junior chiropractors. Given that chiropractic education programs have been unable to develop community-training program for students, it is unlikely that study participants would have a quality concern in this regard.

Coordination is considered to be the process by which the elements of care are linked in overall design. Effective coordination is characterized by the lack of interruption in needed care, and the maintenance of the relatedness between successive sequences of care. The most frequent source of quality judgments concerning coordination can be considered the Time Management Group. For chiropractors, most quality judgments were generated around the ease at which the office could be contacted and appointments booked. Study participants were also enthusiastic about the willingness of the chiropractor to provide care outside of published office hours or their willingness to perform home visits (moderate difference). An appreciable number of poor quality judgments were raised concerning office wait times in chiropractic offices. The remainder of the categories in this group generated greater numbers of quality judgments regarding physician interaction. High quality judgments were awarded for ease of booking appointments, office wait times (minimal differences), and time spent with their physician (minimal differences). While study participants awarded high quality judgments under these circumstances, they also awarded considerable poor quality judgments when physicians failed to make the booking of appointments an easy process (moderate difference), experienced delays in contact to appointment time (minimal differences), created what would be considered unrealistic office wait times (moderate differences) and spent too little time with patients (minimal differences). Study participants clearly generated more quality judgments around time management and coordination of the continuum of care, at least within the family physicians office.

Other coordination quality issues were raised. Results of this study suggest that study participants do not consider timely and appropriate referrals to be a primary professional responsibility of their chiropractors. Most chiropractic care was delivered sequentially over time by a single chiropractor and did not raise concerns from study participants. For physicians, the potential for poor quality judgments around coordination of care is greater. Study participants did consider a number of poor quality judgments around failure to refer (marked difference). Still, these were eclipsed by high quality judgments around the physician’s ability to make timely and appropriate referrals (marked difference) and coordinate care across other health care services and facilities and between other providers and specialists. Indeed, some of these stories were extraordinary. Study participants described their physician as the “quarterback who took charge”, or “sprung into action in a way I had never seen before”, and “made sure I got everything I needed right away” when they were faced with serious health threats. This is in stark contrast to an ongoing cultural awareness of a health system compromised by dangerous wait times and shortages of physician specialists. No study participant provided poor quality judgments that could be considered indictments of the system in this regard. On the contrary, study participants had high praise for their physician’s ability to coordinate their care.

Finally, continuity remains the preservation of past findings, evaluations, and decisions and their use that promotes stability the overall objectives and methods of management. Outcomes of effective coordination and ongoing continuity of care are considered by Donabedian to be accurate diagnosis, appropriate management, and enhanced patient satisfaction. Outside of concerns over record keeping (moderate difference), primarily a poor quality judgment of physicians, continuity did not appear to be a significant source of quality judgments.

Market Justice Implications

In this study it was considered that chiropractic services, not covered by a government health-funding plan, might behave as a market justice commodity. Physician service costs covered under government plans should behave as a social justice commodity. While this study did not expressly set out to determine if the differences seen between the quality judgments of physicians and chiropractors were directly related to the requirement to pay for care, it was anticipated that it would provide some information for consideration for future research.

Cost, which should be a consideration in any discussion around health services delivery, remarkably, generated almost no satisfying or dissatisfying critical incidents; almost to the point where it might be considered a non-issue. Only three of 192 dissatisfying chiropractic critical incidents chronicled concerns over out of pocket cost. No study participant voiced concerns that cost represented a potential barrier to access or created a burdensome financial situation. This may be due to several reasons. First is the potential selection bias of study participants who must have attended their chiropractor for a minimum of one year to be eligible to participate in the study. The inclusion requirements may not sample those study participants for who cost may represent a potential barrier to access or be burdensome. Second are the overall costs. An analysis of annual costs paid for by study participants for chiropractic services suggests that 54% (n = 105) paid less than $200 per year for chiropractic care. Another 21% (n = 42) paid between $201 and $400. Another 10% (n = 19) paid between $401 and $600 annually. In all, 85% (n = 166) of study participants paid $600 or less annually for chiropractic services. This may not represent a sufficient cost to create dissatisfying critical incidents. Still, no study participant voiced satisfaction over the low cost of chiropractic treatment.

In market justice environments it might be expected that some measure of enhanced service be provided to position the competitor more strategically in the marketplace. This does not appear to be the case. Chiropractic dissatisfying experiences were prevalent in the categories of accessibility and comfort. These critical incidents included such concerns as limited parking, lack of wheelchair ramps, heavy doors that impeded access, lack of snow clearing, poor climate control, and absence of simple amenities such as coat racks. No such similar critical incidents were described concerning physician offices. This may be reflective of the 50% decreased earning capacity that Ontario chiropractors witnessed over the ten years from 1993 through 200314. There may simply not be the financial resources available to continue to provide high quality practice facilities.

One might expect other aspects of chiropractic care to be enhanced in a market justice environment. Since study participants are paying for time with their chiropractor one might expect this to be reflected in the Time Management Group. In the Satisfying Group, study participants were more likely to be satisfied with office wait times and time spent with their physician than with their chiropractors. Study participants were more likely to be satisfied with the ability of their chiropractors to book appointments. There is no clear indication that chiropractors provide extra time with patients or limit office wait times as a service strategy within a market justice system. The patterns of satisfying and dissatisfying chiropractic experiences were similar to those of physicians.

Study Implications

The results of this study have implications for practice for both physicians and chiropractors in the Niagara Region and potentially generalizable to other regions.

For physicians, many poor quality judgments were passed in the Standards of Practice Categories. Study participants described that their physicians were often unable to diagnosis their problems, generated an incorrect diagnosis, or failed to diagnosis at all. It must be remembered that this remains the study participant’s perception of their physician’s diagnostic abilities, not a confirmation of the inability to generate a diagnosis. Physicians must be seen to provide an adequate explanation around diagnostic challenges and conundrums to insure that patients are given some confidence in their diagnostic abilities. Similarly physicians must provide adequate explanations of why referrals to specialists are typically not required. What may be self-evident to the physician around a lack of need for referral that requires no explanation may be seen as a failure to explain or refer by the patient. Physicians must be seen to be actively engaged in the record keeping process and conduct a regular review of clinical records to insure that patients have confidence in the preservation of their clinical data. Many patients used to their physicians employing pen and paper records may find that electronic medical records provide little confidence for completeness.

Practice implications for chiropractors are significant. Results of this study suggest that while patients are particularly satisfied concerning the outcomes of treatment, a large number of study participants reported a lack of response to care, protracted recovery, aggravation of complaints, and the emergence of new complaints following treatment. This suggests a greater negative response to care than what is currently thought and chiropractic practitioners should be aware of this in their day-to-day practice. Chiropractors should also be sensitive to criticisms over accessibility issues, amenities, and professional attributes as voiced by their patients.

Implications for Management Both physicians and chiropractors perform aspects of practice management of varying quality. Both health disciplines experienced difficulties with time management and, overall, quality assurance and quality improvement. While some issues of time management may be due to patient volumes and, under some circumstances, shortages of medical practitioners, most time management issues are a product of ineffective or no-existent process management. All time management categories, from ease of appointment booking, office contact to appointment time, office wait times, time with HCP, booking errors, and hours of convenience are outcomes of poor time management. This represented a large source of poor quality judgments for both physicians and chiropractors. More effective time management methods would address many of these quality issues.

The fact that many of the dissatisfying critical incidents occur speaks to the lack of any quality improvement and quality assurance programs in any practitioner’s offices. It is not unreasonable to think that such issues as poor climate control, poor snow clearance, lack of coat racks, dissatisfaction with time management, pain and discomfort from treatment, lack of advocacy, and access to HCP of choice would not be identified and addressed if even basic quality assurance/quality improvement initiatives were put in place.

Implications for Training

The results of this study have implications for undergraduate and continuing education for both physicians and chiropractors. For undergraduate education, curricula should be reviewed and changes implemented that reflect enhanced training, skills, and knowledge around quality management. Health practitioners, partially on the basis of proprietorship, find themselves in the position of being responsible for the quality of care delivered in their practices. Future practitioners must acquire the training prior to graduation to insure they have the capacity to monitor the quality of care in their practice settings and respond to same. For professional associations, regulatory agencies, and post-graduate academic departments, continuing education programs should be developed to provide theoretical and practical training around quality.

Recommendations for Future Research

The quality judgments provided by patients in this study are from patients who attend both physicians and chiropractors. The results are not necessarily generalizable to patients who attend just physicians. In some ways the quality judgments of participants concerning their physicians may be influenced in some manner because they attend chiropractors. Still, the information and tested methodology from this study can be used as a platform for further explorations into quality in both physician’s and chiropractor’s offices.

For chiropractors, the results of this study suggest that further study is required in a number of areas. First is in the matter of treatment outcomes. Donabedian considered that the highest measure of healthcare care quality is care that provides the greatest benefit for the lowest risk. A high number of study participants reported no benefit from care, protracted recovery times, aggravation of presenting complaints, and side effects from treatment. The risks of serious injury from chiropractic treatment have been well documented but the results of this qualitative study suggest the potential for a much broader, previously unrecognized consequence of chiropractic treatment. Second is the self-perception of chiropractors and how they see their role and identity as defined by training versus the perception of their patients. Chiropractors are trained as primary contact practitioners with a responsibility to diagnosis and refer as required. Results of this study suggested that chiropractic patients see their chiropractors as “pain technicians” rewarding their practitioners with high quality judgments when pain is managed effectively, and awarding poor quality judgments when pain complaints are not addressed. Study participants provided few quality judgments around diagnosis and referral by their chiropractors. Instead, study participants generated a large number of quality judgments around their physician’s activities in this regard. This is an unanticipated observation and requires some future consideration.

Limitations of the Study

A number of study limitations exist. The first is the generalizability of the results of this study to other jurisdictions. The results of this study are not necessarily generalizable to other regions within and outside of Ontario. Different payment systems, cultural differences and practitioner availability, among other factors, make generalizability difficult. Second, critical incidents around costs and associated results are limited. Only those individuals who met inclusion criteria, including ongoing chiropractic care greater than one year were included. By design, this creates a bias towards those individuals who can afford ongoing care. Third, the results may only be generalizable to those individuals who attend both a chiropractor and physician. There may be some inherent difference in quality and satisfaction perspectives of patients who see both chiropractors and physicians over patients who see just physicians. And finally, there are those limitations associated with qualitative, inductive studies. While this study did address issues of multiple coding, in part through the use of the label validity process there always remains the possibility of bias and subjectivity in the theming process. Respondent validation exercises were not designed into the process over concerns of demands on participants time. [22]

Sources of Support:

The author received no funding support for the completion of this study.

References:

Donabedian A.

Explorations in quality assessment and monitoring.

Ann Arbor, Michigan: Health Administration Press; 1980.Donabedian A.

Reflections on the effectiveness of quality assurance.

In: Palmer RH, Donabedian A, Povar GS, editors.

Striving for quality in healthcare: an inquiry into policy and practice.

Ann Arbor, Michigan: Health Administration Press; 1991.Institute of Medicine.

Crossing The Quality Chasm:

A New Health System For The 21st Century

Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2001.Romanow RJ.

Building on values: the future of healthcare in Canada.

National Library of Canada. 2002Coulter ID, Hurwitz EL, Adams A, Genoves B, Hays R, Shekelle P.

Patients Using Chiropractors in North America:

Who Are They, and Why Are They in Chiropractic Care?

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002 (Feb 1); 27 (3): 291–298Cherkin DC, MacCormack FA.

Patient Evaluations of Low Back Pain Care

From Family Physicians and Chiropractors

Western Journal of Medicine 1989 (Mar); 150 (3): 351–355Carey TS, Garrett J, Jackman A, McLaughlin C, Fryer J, Smucker DR.

The outcome ad costs of care for acute low back pain among

primary care practitioners, chiropractors, and orthopedic surgeons.

NEJM. 20102010:913–917.

doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510053331406.Hertzman-Miller RP, Morgenstern H, Hurwitz EL, Fei Y, Adams AH, Harber P, et al.

Comparing satisfaction of low back pain patients randomized to receive

medical or chiropractic care: results from the UCLA low-back pain study.

Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1628–1633.

doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.10.1628.Balon J, Aker PD, Crowther ER, Danielson C, Cox PG, O’Shaughnessy D, et al.

A comparison of active and simulated chiropractic manipulation

as adjunctive treatment for childhood asthma.

NEJM. 1998;1998;339:1013–1020.

doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810083391501.Gaumer G.

Factors associated with patient satisfaction with

chiropractic care: survey and review of the literature.

J Manip Physiol Thera. 2005;29:455–462.

doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.06.013.Darr K. Ethics in health services management. Baltimore: Health Professions Press; 1991.

Organization for Health Economic Co-operation and Development.

Paris: 2000. 1999 Health Data.Kral B.

Physician Human Resources in Ontario:

the Crisis Continues. 2010. Available from

http://www.oma.org/Shortage/Data/01crisis.aspMior SA, Laporte A.

Economic and resource status of the chiropractic profession

in Ontario, Canada: a challenge or an opportunity.

J Manip Physiol Thera. 2008;31:104–114.

doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.12.007.Canadian Chiropractic Protective Association 2009.

Available from http://www.ccpaonline.ca.College of Chiropractors of Ontario 2010.

Available from www.cco.on.ca.Flanagan JC.

The critical incident technique.

Psychological Bulletin. 1954;51:327–357.

doi: 10.1037/h0061470.Norman IJ, Redfern SJ, Tomalin DA, Oliver S.

Developing high and low quality nursing care from patients and their nurses.

J Adv Nursing. 1992;17:590–600.

doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1992.tb02837.xFivers G, Fitzpatrick R.

The Critical Incident Technique Bibliography. 20042004

Available from http://www.apa.org/pubs/databases/psycinfo/cit-intro.pdfBitner MJ, Booms BH, Tetreault MS.

The Service Encounter: diagnosing favorable and unfavorable incidents.

J Marketing. 1990;54:71–84Strauss AL.

Quantitative Analysis for Social Scientists.

New York: Cambridge University Press; 1987.Barbpur RS.

Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research:

a case of the tail wagging the dog.

Br Med J. 2001;322:1115–1117.

doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115.

Return to PATIENT SATISFACTION

Since 2-22-2025

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |