A Patient's Guide to Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

Introduction

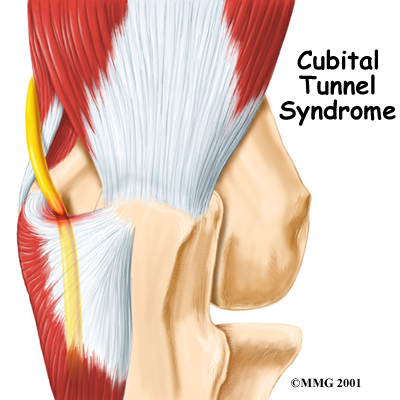

Cubital tunnel syndrome is a condition that

affects the ulnar nerve where it crosses the

inside edge of the elbow. The symptoms are very

similar to the pain that comes from hitting your funny

bone. When you hit your funny bone, you are actually

hitting the ulnar nerve on the inside of the elbow.

There, the nerve runs through a passage called the

cubital tunnel. When this area becomes

irritated from injury or pressure, it can lead to

cubital tunnel syndrome.

This guide will help you understand

- what causes this condition

- ways to make the pain go away

- what you can do to prevent future problems

Anatomy

What is the cubital tunnel?

The ulnar nerve actually starts at the side

of the neck, where the individual nerve roots leave

the spine. The nerve roots exit through small openings

between the vertebrae. These openings are called

neural foramina.

The nerve roots join together to form three main

nerves that travel down the arm to the hand. One of

these nerves is the ulnar nerve.

The ulnar nerve passes through the cubital

tunnel just behind the inside edge of the

elbow. The tunnel is formed by muscle, ligament, and

bone. You may be able to feel it if you straighten

your arm out and rub the groove on the inside edge of

your elbow.

The ulnar nerve passes through the cubital tunnel

and winds its way down the forearm and into the hand.

It supplies feeling to the little finger and half the

ring finger. It works the muscle that pulls the thumb

into the palm of the hand, and it controls the small

muscles (intrinsics) of the hand.

Related Document: A

Patient's Guide to Elbow Anatomy

Causes

What causes cubital tunnel syndrome?

Cubital tunnel syndrome has several possible

causes. Part of the problem may lie in the way the

elbow works. The ulnar nerve actually stretches

several millimeters when the elbow is bent. Sometimes

the nerve will shift or even snap over the bony medial

epicondyle. (The medial epicondyle is the bony

point on the inside edge of the elbow.) Over time,

this can cause irritation.

One common cause of problems is frequent bending of

the elbow, such as pulling levers, reaching, or

lifting. Constant direct pressure on the elbow over

time may also lead to cubital tunnel syndrome. The

nerve can be irritated from leaning on the elbow while

you sit at a desk or from using the elbow rest during

a long drive or while running machinery. The ulnar

nerve can also be damaged from a blow to the cubital

tunnel.

Symptoms

What does cubital tunnel syndrome feel like?

Numbness on the inside of the hand and in the ring

and little fingers is an early sign of cubital tunnel

syndrome. The numbness may develop into pain. The

numbness is often felt when the elbows are bent for

long periods, such as when talking on the phone or

while sleeping. The hand and thumb may also become

clumsy as the muscles become affected.

.jpg)

Tapping or bumping the nerve in the cubital tunnel

will cause an electric shock sensation down to the

little finger. This is called Tinel's sign.

Related Document: A

Patient's Guide to Medial

Epicondylitis

Diagnosis

How will my doctor know I have cubital tunnel

syndrome?

Your doctor will take a detailed medical history.

You will be asked questions about which fingers are

affected and whether or not your hand is weak. You

will also be asked about your work and home activities

and any past injuries to your elbow.

Your doctor will then do a physical exam. The

cubital tunnel is only one of several spots where the

ulnar nerve can get pinched. Your doctor will try to

find the exact spot that is causing your symptoms. The

prodding may hurt, but it is very important to

pinpoint the area causing you trouble.

You may need to do special tests to get more

information about the nerve. One common test is the

nerve conduction velocity (NCV) test. The NCV

test measures the speed of the impulses traveling

along the nerve. Impulses are slowed when the nerve is

compressed or constricted.

The NCV test is sometimes combined with an

electromyogram (EMG). The EMG tests the muscles

of the forearm that are controlled by the ulnar nerve

to see whether the muscles are working properly. If

they aren't, it may be because the nerve is not

working well.

Treatment

How can I make my pain go away?

Nonsurgical Treatment

The early symptoms of cubital tunnel syndrome

usually lessen if you just stop whatever is causing

the symptoms. Anti-inflammatory medications may help

control the symptoms. However, it is much more

important to stop doing whatever is causing the pain

in the first place. Limit the amount of time you do

tasks that require a lot of bending in the elbow. Take

frequent breaks. If necessary, work with your

supervisor to modify your job activities.

If your symptoms are worse at night, a lightweight

plastic arm splint or athletic elbow pad may be worn

while you sleep to limit movement and ease irritation.

Wear it with the pad in the bend of the elbow to keep

the elbow straight while you sleep. You can also wear

the elbow pad during the day to protect the nerve from

the direct pressure of leaning.

Doctors commonly have their patients with cubital

tunnel syndrome work with a physical or occupational

therapist. At first, your therapist will give you tips

how to rest your elbow and how to do your activities

without putting extra strain on your elbow. Your

therapist may apply heat or other treatments to ease

pain. Exercises are used to gradually stretch and

strengthen the forearm muscles.

Surgery

Your symptoms may not go away, even with changes in

your activities and nonsurgical treatments. In that

case, your doctor may recommend surgery to stop damage

to the ulnar nerve.

.jpg)

The goal of surgery is to release the pressure on

the ulnar nerve where it passes through the cubital

tunnel. There are two different kinds of surgery for

cubital tunnel syndrome. It is not clear whether one

operation is better than the other. Ulnar Nerve

Transposition

One method is called ulnar

nerve transposition. In this procedure, the

surgeon forms a completely new tunnel from the

flexor muscles of the forearm. The ulnar nerve

is then moved (transposed) out of the cubital

tunnel and placed in the new tunnel.

The following images show each step

Medial Epicondylectomy

The other method simply removes

the medial epicondyle on the inside edge of the

elbow, a procedure called medial

epicondylectomy. By getting the medial epicondyle

out of the way, the ulnar nerve can then slide through

the cubital tunnel without pressure from the bony

bump.

The following images show each step

Cubital tunnel surgery is often done as an

outpatient procedure. This means you won't have to

stay in the hospital overnight. Surgery can be done

using a general anesthetic, which puts you to

sleep, or a regional anesthetic. A regional

anesthetic blocks the nerves in only one part of your

body. In this case, you would have an axillary

block, which would affect only the nerves of the

arm.

Rehabilitation

What can I expect after treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

If nonsurgical treatments are successful, you may

see improvement in four to six weeks. Your physical or

occupational therapist works with you to ease symptoms

and improve elbow function. Special exercises may be

used to help the ulnar nerve glide within the cubital

tunnel. Treatment progresses to include strengthening

exercises that mimic daily and work activities.

You may need to continue wearing your elbow pad or

splint at night to control symptoms. Try to do your

activities using healthy body and wrist alignment.

Limit repeated motions of the arm and hand, and avoid

positions and activities where the elbow is held in a

bent position.

After Surgery

Recovery after elbow surgery depends on the

procedure used by your surgeon. If you only had the

medial epicondyle removed, you'll have a soft bandage

wrapped over your elbow after surgery. Therapy can

progress quickly after this type of surgery.

Treatments start out with range-of-motion exercises

and gradually work into active stretching and

strengthening. You just need to be careful to avoid

doing too much, too quickly.

Therapy goes slower after ulnar nerve transposition

surgery. You could require therapy for three months.

This is because the flexor muscles had to be sewn

together to form the new tunnel. Your elbow will be

placed in a splint and wrapped in bulky dressing, and

your elbow will be immobilized for three weeks.

When the splint is removed, therapy will begin with

passive movements. In passive exercises, your elbow is

moved, but your muscles stay relaxed. Your therapist

gently moves your arm and gradually stretches your

wrist and elbow. You may be taught how to do passive

exercises at home.

Active therapy starts six weeks after surgery. You

begin to use your own muscle power in active

range-of-motion exercises. Light isometric

strengthening exercises are started. You may begin

careful strengthening of your hand and forearm by

squeezing and stretching special putty. These

exercises work the muscles without straining the

healing tissues.

At about eight weeks, you'll start doing more

active strengthening. Your therapist will give you

exercises to help strengthen and stabilize the muscles

and joints in the wrist, elbow, and shoulder. Other

exercises are used to improve fine motor control and

dexterity of the hand.

Some of the exercises you'll do are designed get

your elbow working in ways that are similar to your

work tasks and sport activities. Your therapist will

help you find ways to do your tasks that don't put too

much stress on your elbow. Before your therapy

sessions end, your therapist will teach you a number

of ways to avoid future problems. |