A Patient's Guide to Dupuytren's Contracture

Introduction

Dupuytren's contracture is a fairly common

disorder of the fingers. It most often affects the ring or

little finger, sometimes both, and often in both hands.

Although the exact cause is unknown, it occurs most often in

middle-aged, white men and is genetic in nature, meaning it

runs in families. This condition is seven times more common

in men than women. It is more common in men of Scandinavian,

Irish, or Eastern European ancestry. Interestingly, the

spread of the disease seems to follow the same pattern as

the spread of Viking culture in ancient times. The disorder

may occur suddenly but more commonly progresses slowly over

a period of years. The disease usually doesn't cause

symptoms until after the age of 40.

This guide will help you understand

- how Dupuytren's contracture develops

- how the disorder progresses, and how you can measure

its progression

- what treatments are available

Anatomy

What part of the hand is affected?

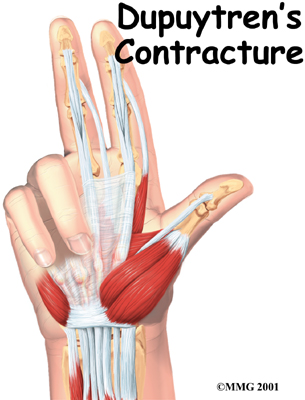

The palm side of the hand contains many nerves, tendons,

muscles, ligaments, and bones. This combination allows us to

move the hand in many ways. The bones give our hand

structure and form joints. Bones are attached to bones by

ligaments. Muscles allow us to bend and straighten

our joints. Muscles are attached to bones by tendons.

Nerves stimulate the muscles to bend and straighten. Blood

vessels carry needed oxygen, nutrients, and fuel to the

muscles to allow them to work normally and heal when

injured. Tendons and ligaments are connective tissue.

Another type of connective tissue, called fascia,

surrounds and separates the tendons and muscles of the

hand.

Lying just under the palm is the palmar fascia, a thin sheet of connective

tissue shaped somewhat like a triangle. This fascia covers

the tendons of the palm of the hand and holds them in place.

It also prevents the fingers from bending too far backward

when pressure is placed against them. The fascia separates

into thin bands of tissue at the fingers. These bands

continue into the fingers where they wrap around the joints

and bones. Dupuytren's contracture forms when the palmar

fascia tightens, causing the fingers to bend.

The condition commonly first shows up as a thick nodule

(knob) or a short cord in the palm of the hand, just below

the ring finger. More nodules form, and the tissues thicken

and shorten until the finger cannot be fully straightened.

Dupuytren's contracture usually affects only the ring and

little finger. The contracture spreads to the joints of the

finger, which can become permanently immobilized.

Related Document: A

Patient's Guide to Hand Anatomy

Causes

Why do I have this problem?

No one knows exactly what causes Dupuytren's contracture.

The condition is rare in young people but becomes more

common with age. When it appears at an early age, it usually

progresses rapidly and is often very severe. The condition

tends to progress more quickly in men than in women.

People who smoke have a greater risk of having

Dupuytren's contracture. Heavy smokers who abuse alcohol are

even more at risk. Recently, scientists have found a

connection with the disease among people who have diabetes.

It has not been determined whether or not work tasks can put

a person at risk or speed the progression of the

disease.

Symptoms

What does Dupuytren's contracture feel like?

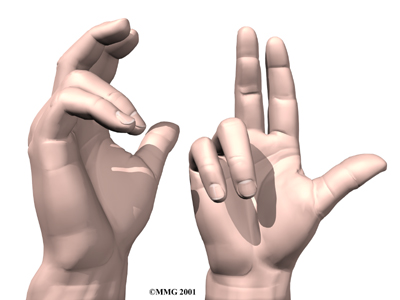

Normally, we are able to control when we bend our fingers

and how much. How much we flex our fingers determines how

small an object we can hold and how tightly we can hold it.

People lose this control as the disorder develops and the

palmar fascia contracts, or tightens. This contracture is

like extra scar tissue just under the skin. As the disorder

progresses, the bending of the finger becomes more and more

severe, which limits the motion of the finger.

Without treatment, the contracture can become so severe

that you cannot straighten your finger, and eventually you

may not be able to use your hand effectively. Because our

fingers are slightly bent when our hand is relaxed, many

people put up with the contracture for a long time. Patients

with this condition usually seek medical advice for cosmetic

reasons or the loss of use of their hand. At times, the

nodules can be very painful. For this reason many patients

are worried that something serious is wrong with their

hand.

Diagnosis

How do doctors identify the problem?

Your doctor will ask you the history of your problem,

such as how long you have had it, whether you've noticed it

getting worse, and whether it has kept you from doing your

daily activities. The doctor will then examine your hand and

finger.

Your doctor can tell if you have a Dupuytren's

contracture by looking at and feeling the palm of your hand

and your fingers. Usually, special tests are unnecessary.

Abnormal fascia will feel thick. Cords and small nodules in

the fascia may be felt as small knots or thick bands under

the skin. These nodules usually form first in the palm of

the hand. As the disorder progresses, nodules form along the

finger. These nodules can be felt through the skin, and you

may have felt them yourself. Depending on the stage of the

disorder, your finger may have started to contract, or

bend.

The amount you are able to bend your finger is called

flexion. The amount you are able to straighten the

finger is called extension. Both are measured in

degrees. Normally, the fingers will straighten out

completely. This is considered zero degrees of flexion (no

contracture). As the contracture causes your finger to bend

more and more, you will lose the ability to completely

straighten out the affected finger. How much of the ability

to straighten out your finger you have lost is also measured

in degrees.

Measurements taken at later follow-up visits will tell

how well treatments are working or how fast the disorder is

progressing. The progression of the disorder is

unpredictable. Some patients have no problems for years, and

then suddenly nodules will begin to grow and their finger

will begin to contract.

The tabletop test may also done. The tabletop test

will show if you can flatten your palm and fingers on a flat

surface. You can follow the progression of the disorder by

doing the tabletop test yourself. Your doctor will tell you

what to look for and when you should return for a follow-up

visit.

Treatment

What can be done for the condition?

There are two types of treatment for Dupuytren's

contracture: surgical and nonsurgical. The best course of

treatment is determined by how far the contractures have

advanced.

Nonsurgical Treatment

In the early stages of this disorder, frequent

examination and follow-up is recommended. Your doctor may

inject cortisone into the painful nodules. Cortisone can be

effective at temporarily easing pain and inflammation. Heat

and stretching treatments given by a physical or

occupational therapist may also be prescribed to control

pain and to try to slow the progression of the

contracture.

Treatment also consists of wearing a splint that keeps

the finger straight. This splint is usually worn at

night.

The nodules of Dupuytren's contracture are almost always

limited to the hand. If you receive regular examinations and

follow your doctor's advice, you may be able to slow the

problems caused by this disorder. However, Dupuytren's

contracture is known to progress, so surgery may be needed

at some point to release the contracture and to prevent

disability in your hand.

Surgery

No hard and fast rule exists as to when surgery is

needed. Surgery is usually recommended when the joint at the

knuckle of the finger reaches 30 degrees of flexion. When

patients have severe problems and require surgery at a

younger age, the problem often comes back later in life.

When the problem comes back or causes severe contractures,

surgeons may decide to fuse the individual finger joints

together. In the worst case, amputation of the finger may be

needed if the contracture restricts the nerves or blood

supply to the finger.

Surgery for the main knuckle of the finger (at the base

of the finger) has better long-term results than when the

middle finger joint is tight. Tightness is more likely to

return after surgery for the middle joint.

Tissue

Release Tissue

Release

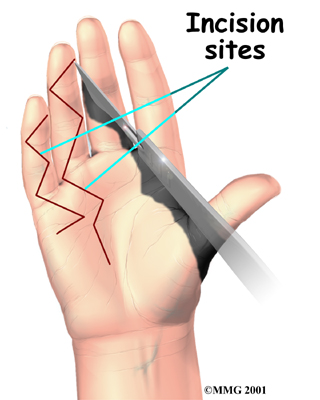

The goal of tissue release surgery is to release the fibrous attachments between the palmar

fascia and the tissues around it, thereby releasing the

contracture. Once released, finger movement should be

restored to normal. If the problem is not severe, it may be

possible to free the contracture simply by cutting the cord

under the skin. If the palmar fascia is more involved and

more than one finger is bent, your surgeon may take out the

whole sheet of fascia. Palmar Fascia Removal

Removal of the entire palmar fascia will usually give a very good

result. The cure is often permanent but depends a great deal

on the success of doing the physical or occupational therapy

as prescribed. Little ill effect is caused by removing the

entire palmar fascia, although the fingers may bend backward

slightly more than normal. If you decide to have this

surgery, you must commit to doing the therapy needed to make

your surgery as successful as possible. Skin Graft

Method

A skin graft may be needed if the skin surface has

contracted so much that the finger cannot relax as it should

and the palm cannot be stretched out flat. Surgeons graft

skin from the wrist, elbow, or groin. The skin is grafted

into the area near the incision to give the finger extra

mobility for movement.

Related Document: A

Patient's Guide to Dupuytren's Contracture

Surgery

Rehabilitation

What should I expect after treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

The ability of nonsurgical treatments to slow or actually

reverse the contracture is not all that promising. The

contracture usually requires surgery at some point. Heat,

stretching, and a finger splint seem to help the most. These

treatments may be directed by a physical or occupational

therapist. Sessions may be scheduled for a few visits per

week up for up to six weeks, but after that, you'll probably

be instructed to continue using the splint and doing the

stretches as part of a home program for several months.

After Surgery

Your hand will be bandaged with a well-padded dressing

and a splint for support after surgery. Physical or

occupational therapy sessions may be needed after surgery

for up to six weeks. Visits will include heat treatments,

soft tissue massage, and vigorous stretching. Therapy

treatments after surgery can make the difference in a

successful result after surgery. |