The important structures of the elbow can be divided into

several categories. These include

- bones and joints

- ligaments and tendons

- muscles

- nerves

- blood vessels

Bones and Joints

The bones of the elbow are the humerus (the upper

arm bone), the ulna (the larger bone of the forearm,

on the opposite side of the thumb), and the radius

(the smaller bone of the forearm on the same side as the

thumb). The elbow itself is essentially a hinge joint,

meaning it bends and straightens like a hinge. But there is

a second joint where the end of the radius (the radial head) meets the humerus. This joint is

complicated because the radius has to rotate so that you can

turn your hand palm up and palm down. At the same time, it

has to slide against the end of the humerus as the elbow

bends and straightens. The joint is even more complex

because the radius has to slide against the ulna as it

rotates the wrist as well. As a result, the end of the

radius at the elbow is shaped like a smooth knob with a cup

at the end to fit on the end of the humerus. The edges are

also smooth where it glides against the ulna.

Articular cartilage is the material that covers

the ends of the bones of any joint. Articular cartilage can

be up to one-quarter of an inch thick in the large,

weight-bearing joints. It is a bit thinner in joints such as

the elbow, which don't support weight. Articular cartilage

is white, shiny, and has a rubbery consistency. It is

slippery, which allows the joint surfaces to slide against

one another without causing any damage.

The function of articular cartilage is to absorb shock

and provide an extremely smooth surface to make motion

easier. We have articular cartilage essentially everywhere

that two bony surfaces move against one another, or

articulate. In the elbow, articular cartilage covers

the end of the humerus, the end of the radius, and the end

of the ulna.

Ligaments and Tendons

There are several important ligaments in the

elbow. Ligaments are soft tissue structures that connect

bones to bones. The ligaments around a joint usually combine

together to form a joint capsule. A joint capsule is

a watertight sac that surrounds a joint and contains

lubricating fluid called synovial fluid.

In the elbow, two of the most important ligaments are the

medial collateral ligament and the lateral collateral ligament. The medial

collateral is on the inside edge of the elbow, and the

lateral collateral is on the outside edge. Together these

two ligaments connect the humerus to the ulna and keep it

tightly in place as it slides through the groove at the end

of the humerus. These ligaments are the main source of

stability for the elbow. They can be torn when there is an

injury or dislocation to the elbow. If they do not heal

correctly the elbow can be too loose, or unstable.

There is also an important ligament called the annular ligament that wraps around the radial

head and holds it tight against the ulna. The word

annular means ring shaped, and the annular ligament

forms a ring around the radial head as it holds it in place.

This ligament can be torn when the entire elbow or just the

radial head is dislocated.

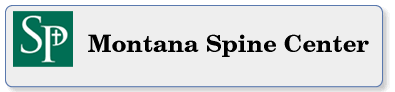

There are several important tendons around the

elbow. The biceps tendon attaches the large biceps

muscle on the front of the arm to the radius. It allows

the elbow to bend with force. You can feel this tendon

crossing the front crease of the elbow when you tighten the

biceps muscle.

The triceps tendon connects the large triceps

muscle on the back of the arm with the ulna. It allows

the elbow to straighten with force, such as when you perform

a push-up.

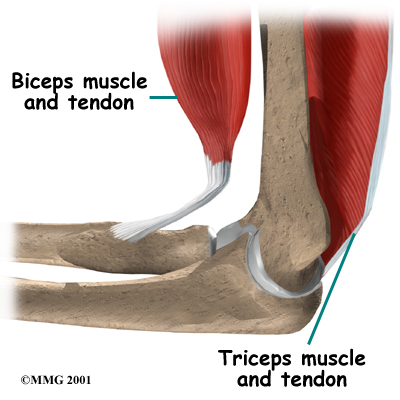

The muscles of the forearm cross the elbow and attach to

the humerus. The outside, or lateral, bump just above the

elbow is called the lateral epicondyle. Most of the muscles that

straighten the fingers and wrist all come together in one

tendon to attach in this area. The inside, or medial, bump

just above the elbow is called the medial epicondyle. Most of the muscles that

bend the fingers and wrist all come together in one tendon

to attach in this area. These two tendons are important to

understand because they are a common location of

tendonitis.

Muscles

The main muscles that are important at the elbow have

been mentioned above in the discussion about tendons. They

are the biceps, the triceps, the wrist extensors

(attaching to the lateral epicondyle) and the wrist

flexors (attaching to the medial epicondyle).

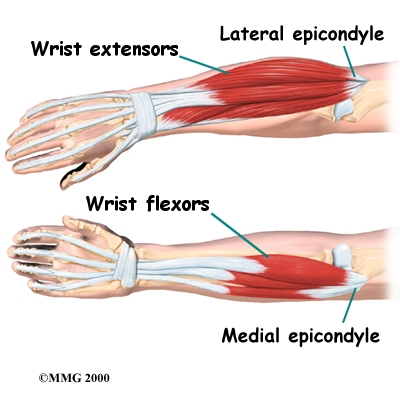

Nerves

Nerves

All of the nerves that travel down the arm pass across the elbow. Three main nerves begin

together at the shoulder: the radial nerve, the

ulnar nerve, and the median nerve. These

nerves carry signals from the brain to the muscles that move

the arm. The nerves also carry signals back to the brain

about sensations such as touch, pain, and temperature.

Some of the more common problems around the elbow are

problems of the nerves. Each nerve travels through its own

tunnel as it crosses the elbow. Because the elbow must bend

a great deal, the nerves must bend as well. Constant bending

and straightening can lead to irritation or pressure on the

nerves within their tunnels and cause problems such as pain,

numbness, and weakness in the arm and hand.

Blood

Vessels

Traveling along with the nerves are the large vessels

that supply the arm with blood. The largest artery is the brachial artery that travels across the front

crease of the elbow. If you place your hand in the bend of

your elbow, you may be able to feel the pulsing of this

large artery. The brachial artery splits into two branches just below the elbow: the

ulnar artery and the radial artery that

continue into the hand. Damage to the brachial artery can be

very serious because it is the only blood supply to the

hand.