A Patient's Guide to Impingement Syndrome

Introduction

The shoulder is a very complex piece of machinery.

Its elegant design gives the shoulder joint great

range of motion, but not much stability. As long as

all the parts are in good working order, the shoulder

can move freely and painlessly.

Many people refer to any pain in the shoulder as

bursitis. The term bursitis really only means

that the part of the shoulder called the bursa

is inflamed. Tendonitis is when a tendon gets

inflamed. This can be another source of pain in the

shoulder. Many different problems can cause

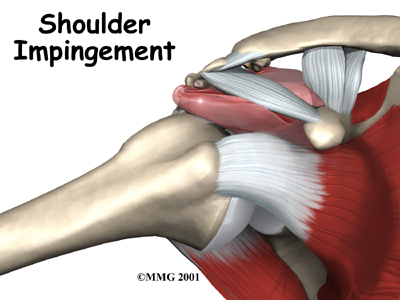

inflammation of the bursa or tendons. Impingement

syndrome is one of those problems. Impingement

syndrome occurs when the rotator cuff tendons rub

against the roof of the shoulder, the

acromion.

This guide will help you understand

- what happens in your shoulder when you have

impingement syndrome

- what tests your doctor will run to diagnose this

condition

- how you can relieve your symptoms.

Anatomy

What part of the shoulder is affected?

The shoulder is made up of three

bones: the scapula (shoulder blade), the

humerus (upper arm bone), and the

clavicle (collarbone).

The rotator cuff connects the humerus to the

scapula. The rotator

cuff is formed by the tendons of four

muscles: the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres

minor, and subscapularis.

Tendons attach muscles to bones. Muscles move the

bones by pulling on the tendons. The rotator cuff

helps raise and rotate the arm.

As the arm is raised, the rotator cuff also keeps

the humerus tightly in the socket

of the scapula, the glenoid. The upper part

of the scapula that makes up the roof of the shoulder

is called the acromion.

A bursa

is located between the acromion and the rotator cuff

tendons. A bursa is a lubricated sac of tissue that

cuts down on the friction between two moving parts.

Bursae are located all over the body where tissues

must rub against each other. In this case, the bursa

protects the acromion and the rotator cuff from

grinding against each other.

Related Document: A

Patient's Guide to Shoulder Anatomy

Causes

Why do I have problems with shoulder

impingement?

Usually, there is enough room between the acromion

and the rotator cuff so that the tendons slide easily

underneath the acromion as the arm is raised. But each

time you raise your arm, there is a bit of rubbing or

pinching on the tendons and the bursa. This rubbing or

pinching action is called impingement.

Impingement occurs to some degree in everyone's

shoulder. Day-to-day activities that involve using the

arm above shoulder level cause some impingement.

Usually it doesn't lead to any prolonged pain. But

continuously working with the arms raised overhead,

repeated throwing activities, or other repetitive

actions of the shoulder can cause impingement to

become a problem. Impingement becomes a problem when

it causes irritation or damage to the rotator cuff

tendons.

Raising the arm tends to force the humerus against

the edge of the acromion. With overuse, this can cause

irritation and swelling of the bursa. If any other

condition decreases the amount of space between the

acromion and the rotator cuff tendons, the impingement

may get worse.

Bone spurs can reduce the space available

for the bursa and tendons to move under the acromion.

Bone spurs are bony points. They are commonly caused

by wear and tear of the joint between the collarbone

and the scapula, called the acromioclavicular

(AC) joint. The AC joint is directly above the bursa

and rotator cuff tendons.

.jpg)

In some people, the space is too small because the

acromion is oddly

sized. In these people, the acromion tilts too far

down, reducing the space between it and the rotator

cuff.

Symptoms

What does impingement syndrome feel like?

Impingement syndrome causes generalized shoulder

aches in the condition's early stages. It also causes

pain when raising the arm out to the side or in front

of the body. Most patients complain that the pain

makes it difficult for them to sleep, especially when

they roll onto the affected shoulder.

A reliable sign of impingement syndrome is a sharp

pain when you try to reach into your back pocket. As

the condition worsens, the discomfort increases. The

joint may become stiffer. Sometimes a catching

sensation is felt when you lower your arm. Weakness

and inability to raise the arm may indicate that the

rotator cuff tendons are actually torn.

Related Document: A

Patient's Guide to Rotator Cuff

Tears

Diagnosis

What tests will my doctor run?

The diagnosis of bursitis or tendonitis caused by

impingement is usually made on the basis of your

medical history and physical examination. Your doctor

will ask you detailed questions about your activities

and your job, because impingement is frequently

related to repeated overhead activities.

Your doctor may order X-rays to look for an

abnormal acromion or bone spurs around the AC joint. A

magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) scan may be performed

if your doctor suspects a tear of the rotator cuff

tendons. An MRI is a special imaging test that uses

magnetic waves to create pictures that show the

tissues of the shoulder in slices. The MRI scan shows

tendons as well as bones. The MRI scan is painless and

requires no needles.

An arthrogram may also be used to detect

rotator cuff tears. The arthrogram is an older test

than the MRI, but it is still widely used. It involves

injecting dye into the shoulder joint and then taking

several X-rays. If the dye leaks out of the shoulder

joint, it suggests that there is a tear in the rotator

cuff tendons.

In some cases, it is unclear whether the pain is

coming from the shoulder or a pinched nerve in the

neck. An injection of a local anesthetic (such

as lidocaine) into the bursa can confirm that the pain

is in fact coming from the shoulder. If the pain goes

away immediately after the injection, then the bursa

is the most likely source of the pain. Pain from a

pinched nerve in the neck would almost certainly not

go away after an injection into the

shoulder.

Treatment

What treatment options are available?

Nonsurgical Treatment

Doctors usually start by prescribing nonsurgical

treatment. You may be prescribed anti-inflammatory

medications such as aspirin or ibuprofen. Resting the

sore joint and putting ice on it can also ease pain

and inflammation. If the pain doesn't go away, an

injection of cortisone into the joint may help.

Cortisone is a strong medication that decreases

inflammation and reduces pain. Cortisone's effects are

temporary, but it can give very effective relief for

up to several months.

Your doctor may also prescribe sessions with a

physical or occupational therapist. Your therapist

will use various treatments to calm inflammation,

including heat and ice. Therapists use hands-on

treatments and stretching to help restore full

shoulder range of motion. Improving strength and

coordination in the rotator cuff and shoulder blade

muscles lets the humerus move in the socket without

pinching the tendons or bursa under the acromion. You

may need therapy treatments for four to six weeks

before you get full shoulder motion and function

back.

Surgery

If you are still having problems after trying

nonsurgical treatments, your doctor may recommend

surgery. Subacromial Decompression

The goal of surgery is to increase the space

between the acromion and the rotator cuff tendons.

Taking pressure off the tissues under the acromion is

called subacromial decompression. The surgeon

must first remove any bone spurs under the acromion

that are rubbing on the rotator cuff tendons and the

bursa. Usually the surgeon also removes a small part

of the acromion to give the tendons even more space.

In patients who have a downward tilt of the acromion,

more of the bone may need to be removed. Surgically

cutting and shaping the acromion is called

acromioplasty. It gives the surgeon another

step to get pressure off (decompress) the tissues

between the humerus and the acromion. Resection

Arthroplasty

Impingement may not be the only problem in an aging

or overused shoulder. It is very common to also see

degeneration from arthritis in the AC joint. If there

is reason to believe that the AC joint is arthritic,

the end of the clavicle may be removed during

impingement surgery. This procedure is called a

resection arthroplasty. This procedure involves

removing the last inch of the clavicle. Scar tissue

then fills the space left between the clavicle and the

acromion, forming a false joint. The idea is to stop

the pain caused by bone rubbing against bone. The scar

tissue creates a stable, flexible connection between

the clavicle and the scapula.

Related Document: A

Patient's Guide to Osteoarthritis of the

Acromioclavicular Joint Arthroscopic

Procedure

In some cases impingement surgery can be done with

an arthroscope.

The arthroscope is a small TV camera that can be

inserted through a small incision. This allows the

surgeon to see the area where he or she is working on

a TV screen. Through other small incisions, the

surgeon can insert special instruments to cut and

grind away bone. If your surgery is done with the

arthroscope, you may be able to go home the same

day. Open Procedure

In other cases, an open incision is made to

allow removal of the bone. Usually an incision about

three or four inches long is made over the top of the

shoulder. The surgeon removes any bone spurs and a

part of the acromion. The surgeon then smooths the

rough ends of the bone. If necessary, the surgeon will

do a resection arthroplasty on the AC joint. If you

have open surgery, you may need to spend a night or

two in the hospital.

.jpg)

View

animation of bone spur removal

Rehabilitation

What should I expect after treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

Even if you don't need surgery, you may need to

follow a program of rehabilitation exercises. Your

doctor may recommend that you work with a physical or

occupational therapist. Your therapist can create an

individualized program of strengthening and stretching

for your shoulder and rotator cuff.

It is important to maintain the strength in the

muscles of the rotator cuff. These muscles help

control the stability of the shoulder joint.

Strengthening these muscles can actually decrease the

impingement of the acromion on the rotator cuff

tendons and bursa. Your therapist can also evaluate

your workstation or the way you use your body when you

do your activities and suggest changes to avoid

further problems.

After Surgery

Rehabilitation after shoulder surgery can be a slow

process. You will probably need to attend therapy

sessions for several weeks, and you should expect full

recovery to take several months. Getting the shoulder

moving as soon as possible is important. However, this

must be balanced with the need to protect the healing

muscles and tissues.

Your surgeon may have you wear a sling to support

and protect the shoulder for a few days after surgery.

Ice and electrical stimulation treatments may be used

during your first few therapy sessions to help control

pain and swelling from the surgery. Your therapist may

also use massage and other types of hands-on

treatments to ease muscle spasm and pain.

Therapy can progress quickly after a simple

arthroscopic procedure. Treatments start out with

range-of-motion exercises and gradually work into

active stretching and strengthening. You just need to

be careful to avoid doing too much, too quickly.

Therapy goes slower after open surgery in which the

shoulder muscles have been cut. Therapists will

usually wait up to two weeks before starting

range-of-motion exercises. Exercises begin with

passive movements. During passive exercises, your

shoulder joint is moved, but your muscles stay

relaxed. Your therapist gently moves your joint and

gradually stretches your arm. You may be taught how to

do passive exercises at home.

Active therapy starts four to six weeks after

surgery. You use your own muscle power in active

range-of-motion exercises. You may begin with light

isometric strengthening exercises. These exercises

work the muscles without straining the healing

tissues.

At about six weeks you start doing more active

strengthening. Exercises focus on improving the

strength and control of the rotator cuff muscles and

the muscles around the shoulder blade. Your therapist

will help you retrain these muscles to keep the ball

of the humerus in the socket. This helps your shoulder

move smoothly during all your activities.

Some of the exercises you'll do are designed get

your shoulder working in ways that are similar to your

work tasks and sport activities. Your therapist will

help you find ways to do your tasks that don't put too

much stress on your shoulder. Before your therapy

sessions end, your therapist will teach you a number

of ways to avoid future problems. |