The important structures of the shoulder can be divided

into several categories. These include

- bones and joints

- ligaments and tendons

- muscles

- nerves

- blood vessels

- bursae

Bones and Joints

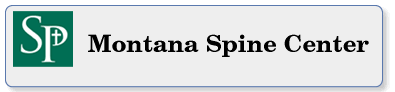

The bones of the shoulder are the humerus (the

upper arm bone), the scapula (the shoulder blade),

and the clavicle (the collar bone). The roof of the

shoulder is formed by a part of the scapula called the

acromion.

There are actually four joints that make up the shoulder.

The main shoulder joint, called the glenohumeral joint, is formed where the ball of

the humerus fits into a shallow socket on the scapula. This

shallow socket is called the glenoid.

The acromioclavicular (AC) joint is where the clavicle

meets the acromion. The sternoclavicular (SC) joint supports the

connection of the arms and shoulders to the main skeleton on

the front of the chest.

A false joint is formed where the shoulder blade

glides against the thorax (the rib cage). This joint,

called the scapulothoracic joint, is important because it

requires that the muscles surrounding the shoulder blade

work together to keep the socket lined up during shoulder

movements.

Articular cartilage is the material that covers

the ends of the bones of any joint. Articular cartilage is

about one-quarter of an inch thick in most large,

weight-bearing joints. It is a bit thinner in joints such as

the shoulder, which don't normally support weight. Articular

cartilage is white and shiny and has a rubbery consistency.

It is slippery, which allows the joint surfaces to slide

against one another without causing any damage. The function

of articular cartilage is to absorb shock and provide an

extremely smooth surface to make motion easier. We have

articular cartilage essentially everywhere that two bony

surfaces move against one another, or articulate. In

the shoulder, articular cartilage covers the end of the

humerus and socket area of the glenoid on the scapula.

Ligaments

and Tendons

There are several important ligaments in the

shoulder. Ligaments are soft tissue structures that connect

bones to bones. A joint capsule is a watertight sac

that surrounds a joint. In the shoulder, the joint capsule

is formed by a group of ligaments that connect the humerus

to the glenoid. These ligaments are the main source of

stability for the shoulder. They help hold the shoulder in

place and keep it from dislocating.

Ligaments attach the clavicle to the acromion in the AC

joint. Two ligaments connect the clavicle to the scapula by

attaching to the coracoid process, a bony knob that

sticks out of the scapula in the front of the shoulder.

A special type of ligament forms a unique structure

inside the shoulder called the labrum. The labrum is

attached almost completely around the edge of the glenoid.

When viewed in cross section, the labrum is wedge-shaped.

The shape and the way the labrum is attached create a deeper

cup for the glenoid socket. This is important because the

glenoid socket is so flat and shallow that the ball of the

humerus does not fit tightly. The labrum creates a deeper

cup for the ball of the humerus to fit into.

The labrum is also where the biceps tendon attaches

to the glenoid. Tendons are much like ligaments,

except that tendons attach muscles to bones. Muscles move

the bones by pulling on the tendons. The biceps tendon runs

from the biceps muscle, across the front of the shoulder, to

the glenoid. At the very top of the glenoid, the biceps

tendon attaches to the bone and actually becomes part of the

labrum. This connection can be a source of problems when the

biceps tendon is damaged and pulls away from its attachment

to the glenoid.

The tendons of the rotator cuff are the next layer

in the shoulder joint. Four rotator cuff tendons connect the

deepest layer of muscles to the humerus.

Muscles

The rotator cuff tendons attach to the deep rotator cuff

muscles. This group of muscles lies just outside the

shoulder joint. These muscles help raise the arm from the

side and rotate the shoulder in the many directions. They

are involved in many day-to-day activities. The rotator cuff

muscles and tendons also help keep the shoulder joint stable

by holding the humeral head in the glenoid socket.

The large deltoid muscle is the outer layer of shoulder

muscle. The deltoid is the largest, strongest muscle of the

shoulder. The deltoid muscle takes over lifting the arm once

the arm is away from the side.

Nerves

All of the nerves that travel down the arm pass through the

axilla (the armpit) just under the shoulder joint.

Three main nerves begin together at the shoulder: the

radial nerve, the ulnar nerve, and the

median nerve. These nerves carry the signals from the

brain to the muscles that move the arm. The nerves also

carry signals back to the brain about sensations such as

touch, pain, and temperature.

Blood Vessels

Traveling along with the nerves are the large vessels

that supply the arm with blood. The large axillary artery travels through the axilla. If

you place your hand in your armpit, you may be able to feel

the pulsing of this large artery. The axillary artery has

many smaller branches that supply blood to different parts

of the shoulder. The shoulder has a very rich blood

supply.

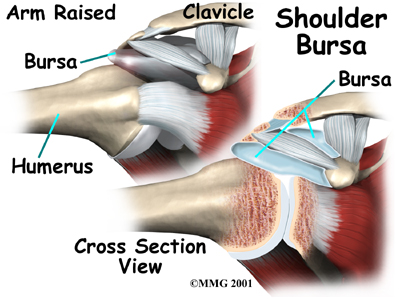

Bursae

Sandwiched between the rotator cuff muscles and the outer

layer of large bulky shoulder muscles are structures known

as bursae. Bursae are everywhere in the body. They

are found wherever two body parts move against one another

and there is no joint to reduce the friction. A single bursa

is simply a sac between two moving surfaces that contains a

small amount of lubricating fluid.

Think of a bursa like this: If you press your hands

together and slide them against one another, you produce

some friction. In fact, when your hands are cold you may rub

them together briskly to create heat from the friction. Now

imagine that you hold in your hands a small plastic sack

that contains a few drops of salad oil. This sack would let

your hands glide freely against each other without a lot of

friction.