MYMOP - Measure Yourself Medical Outcome Profile

Original Editor - Abbey Wright

Top Contributors - Abbey Wright, Oyemi Sillo and Kim Jackson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

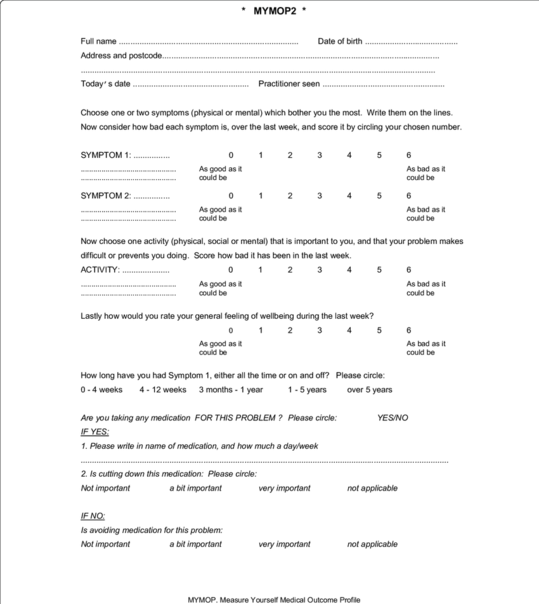

The Measure Yourself Medical Outcome Profile (MYMOP) tool is a generic patient specific outcome tool to assess general health which was originally created in 1996, since then several editions have been produced including the MYMOP2 (which is pictured below)[1][2]. It can be used for musculo-skeletal or respiratory conditions and gives an individualized approach and measure regarding the symptoms and activities that are effected by the symptoms[3].

The second version of the MYMOP also asks the patient about analgesia including the doses which in the first version was not included.

Description[edit | edit source]

The MYMOP tool is completed in the initial consultation. One or two symptoms are listed which are effected by the patient's condition such as "right leg weakness", this is then rated by the patient on a scale 0-6 taking into consideration their symptoms over the last week. This rating scale should be done by the patient and not influenced by the practitioner.[5]

- 0 being: "as good as it can be"

- 6 being: "as bad as it could be".

The patient would then choose an activity that has been effected by the symptom, and again rate the activity on a scale of 0-6 over the last week. The patient can also rate their well-being on the same scale however it is not essential for the data analysis.

On the initial MYMOP2 it also asks for medication usage and the patient's opinion on taking medication.

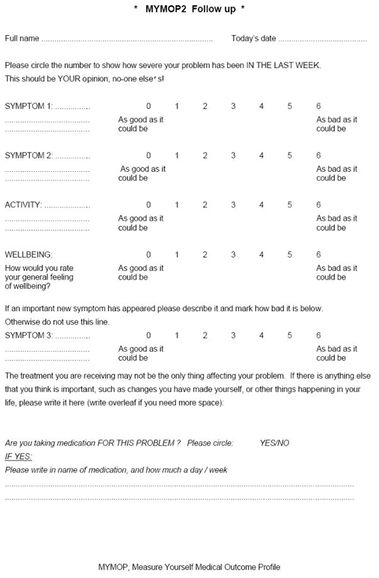

On follow up a similar MYMOP2 is completed with the same 0-6 scale but giving the option to add a third symptom and less detail regarding medication. The follow up MYMOP2 can be done mid-way through treatment as well as on discharge to give a measure of progress for both patient and practitioner.

A minimum clinically important change in score after intervention should be between 0.5-1.0: any change greater than 1.0 can be considered clinically significant.[2]

See MYMOP2 scoring for how to score the initial and follow up MYMOP2.

Advantages[edit | edit source]

- Patient centered[5]

- The MYMOP has been shown to be effective at measuring clinical effectiveness associated with acupuncture treatments which are typically difficult to prove clinical improvement. [7]

- Simple to administer[7]

- Sensitive to clinical change[7][8]

- Can be used in acute or persistent conditions[2]

- Improves patient-practitioner communication[8]

Disadvantages[edit | edit source]

The initial version was criticized due to it not including information regarding medication used for the condition, this has been added in the second version of the MYMOP2 (which is pictured above).[9] It does require some therapist involvement on the initial questionnaire so is not suitable for postal use.

It also requires patients to list the "most severe" problems so in patients with multiple issues it can be difficult for them to identify the most severe problem.

Evidence[edit | edit source]

The MYMOP2 has been shown to be validated and highly sensitive/responsive outcome measure. [2][5]

Resources[edit | edit source]

Related Articles[edit | edit source]

Further patient specific measures include:

- Patient Specific Functional Scale

- Quality of Life measures that have been used in multiple studies referenced on this page include:

- EQ-5D

- SF36 (Short Form 36)

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Mirza S, Salisbury C, Hopper C, Foster N, Montgomery A. Comparing sensitivity to change of two patient-reported outcome measures in a randomised trial of patients referred for physiotherapy services. Trials. 2013 Nov 1;14(S1):O50.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Polus BI, Kimpton AJ, Walsh MJ. Use of the measure your medical outcome profile (MYMOP2) and W-BQ12 (Well-Being) outcomes measures to evaluate chiropractic treatment: an observational study. Chiropractic & manual therapies. 2011 Dec;19(1):7.

- ↑ Paterson C, Langan CE, McKaig GA, Anderson PM, Maclaine GD, Rose LB, Walker SJ, Campbell MJ. Assessing patient outcomes in acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis: the measure your medical outcome profile (MYMOP), medical outcomes study 6-item general health survey (MOS-6A) and EuroQol (EQ-5D). Quality of Life Research. 2000 May 1;9(5):521-7.

- ↑ getwelluk. What is MYMOP? Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IS4pblMO5RI [last accessed 15/1/2023]

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 Hermann K, Kraus K, Herrmann K, Joos S. A brief patient-reported outcome instrument for primary care: German translation and validation of the Measure Yourself Medical Outcome Profile (MYMOP). Health and quality of life outcomes. 2014 Dec;12(1):112.

- ↑ getwelluk. How Do I Use MYMOP? Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w8d0w38n-eI [last accessed 15/1/2023]

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 Hull SK, Page CP, Skinner BD, Linville JC, Coeytaux RR. Exploring outcomes associated with acupuncture. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine. 2006 Apr 1;12(3):247-54.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 Paterson C. Measuring outcomes in primary care: a patient generated measure, MYMOP, compared with the SF-36 health survey. Bmj. 1996 Apr 20;312(7037):1016-20.

- ↑ Paterson C, Britten N. In pursuit of patient-centred outcomes: a qualitative evaluation of the ‘Measure Yourself Medical Outcome Profile’. Journal of health services research & policy. 2000 Jan;5(1):27-36.