Chiropractic Care during Pregnancy:

Survey of 100 Patients Presenting

to a Private Clinic in Oslo, NorwayThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Clinical Chiropractic Pediatrics 2010 (Dec); 11 (2): 771–774 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Elisabeth Aas-Jakobsen, BS, DC, MSc and Joyce E. Miller, BS, DC, DABCO

Private practice,

Oslo, Norway

elisabeth@gmail.comIntroduction

Musculoskeletal (MSK) problems in pregnancy constitute a tremendous cost to society, both in regards to sick leave and chronic pain, and are a major public health concern. (In Norway one-third of all pregnant women are on sick leave at any given time, and many of these because of back pain). There is little agreement on the best treatment for the various MSK problems in pregnancy and very little is known about the efficacy of chiropractic treatment in pregnancy. However, chiropractic care has been shown to be both popular with patients during pregnancy, as well as being considered safe and appropriate by chiropractors. The purpose of this paper is to describe a survey which investigated the characteristics of pregnant women who sought chiropractic care in Norway

Methods

The design of this study was a cross-sectional survey which was designed to collect demographic data from the first 100 pregnant women who presented in consecutive order within a specific time frame to a chiropractic clinic in Oslo, Norway. The data were abstracted from patient records of new patients who were pregnant and consulted the clinic from September 2007 to December 2008. Only the data from treatments during pregnancy were used; treatments after the end of pregnancy were not included. Only the data that systematically had been recorded in all the files were used. Inclusion criteria were that the patients were pregnant on presentation to the clinic, that they spoke Norwegian and received more than one treatment. If they had sought other treatment earlier in the same pregnancy, they were still included. Exclusion criteria were receiving only one treatment (to avoid patients travelling through the area, and to avoid any assumptions of patients potentially not returning after the first treatment where it was impossible to re-interview or re-examine the patient). Only treatments during pregnancy were included. Episode of care was throughout the pregnancy, and did not extend past pregnancy.

All data were held completely confidentially and no patient was identifiable. All patient data were coded without use of names or identifying features. Patient’s files on the computer were transcribed to an Excel spreadsheet. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data.

This study was approved by the Anglo-European College of Chiropractic Research Ethics Sub-Committe for postgraduate research in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. No further approval was required in Norway. There were no funding issues or conflicts of interest.

Results

The mean age of the patients presenting to the chiropractor was 32.5 years (range 25-42). Forty percent (n=40/100) were in the group 29-32 years old, 40% were in the group 33-36 years old and 20% were under age 28, or 37 or above. About half of the patients (47%) were in their first pregnancy, the other half (49%) in their second pregnancy, and only a few (4%) in their third pregnancy. For 32% of the patients, the contact in this office was the first time they had ever received any care for any musculoskeletal problems in the health care system regardless of pregnancy status. Thirty eight percent had been to a chiropractor before, either before they were pregnant, or in a previous pregnancy. Thirty percent had been to a physiotherapist previously, either in the present pregnancy or an earlier pregnancy, or for any condition before they were pregnant.

In this clinic 44% were referred to the clinic by friends or family and 48% referred by other health professionals, 23% received advice from their midwife to contact the clinic, 15% from their medical doctor, and 10% from their physiotherapist.

About 90% of the women had pelvic pain as the main reason why they had contacted the clinic during pregnancy. Six out of 10 had back pain, and 6 out of 10 had specific thoracic pain. Three out 10 had neck pain, 29% had symphysis pubis pain, 15% experienced headaches and 2% migraines. Overall, 82% experienced a combination of pain sites.

Fifty-five percent of the patients received care in the pelvic/lumbar, thoracic and cervical areas. Forty-one percent received pelvic/lumbar and thoracic treatment and 4% in the pelvic/sacrum areas only.

When looking at the 82% who experienced a combination of pain sites, it was most common to have a combination of 3 sites, then 2, 4 or a combination of 5 or more.

In this study, 44% had experienced some form of back pain prior to this pregnancy. Twenty-one percent had experienced pain in an earlier pregnancy. Thirty-five percent had no previous experience with back pain.

The average gestational age was 26.5 weeks. The mode was 26 weeks.

Fifty-two percent of the patients were in their second trimester (eleven percent in gestational week 26), 43% were in their third trimester (nine percent in gestational week 32 and ten percent in week 35) and 5% were in their first trimester.

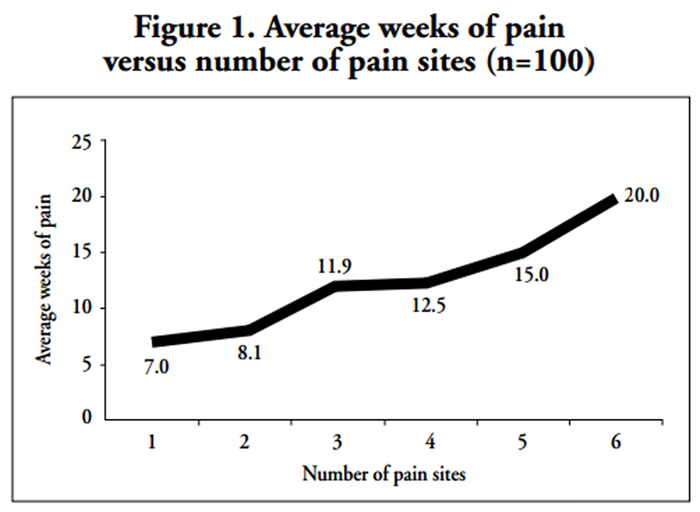

Figure 1

Figure 1 Thirty-six percent of the patients noted that their pain had started at what they defined as the “beginning” of the pregnancy. Sixteen percent had had pain for 1-2 weeks, 10% 3-4 weeks, 8% 5-7 weeks and 20% had had pain for more than 2 months duration before clinical prensentation. Those with the greatest number of pain sites had experienced it for the longest duration (Figure 1).

The most common number of treatments was 8.5 (range 2-19). Forty-seven percent received between 7-12 treatments, 34% received 2-6 treatments and 19% received more than 13 treatments. Many of the patients received care after birth; however these were not included. Number of treatments generally increased with the number of pain sites (Figure 2).

The patients who had had no previous experience with back or pelvic pain sought care on average after 4.5 weeks of pain. The patients who had had previous back pain not related to pregnancy waited on average 12.5 weeks before seeking care. Those women who had experienced back or pelvic pain in a previous pregnancy waited on average 14 weeks before consulting a chiropractor.

When studying the patients who waited the longest before seeking care (more than 20 weeks), it was found that only the women who had had earlier back pain waited that long before seeking care, 10 with a previous back pain history and 3 with pain in an earlier pregnancy. When looking at those patients who sought care within 1-3 weeks of pain, it was found that none of these 12 had had any previous experience with back pain. When looking at the trimester when the patients presented as well as how long they had had pain before they sought care, it was found that in the first trimester the patients had had pain for an average of 5.4 weeks, in the second trimester an average of 9.6 weeks and in the last trimester the patients had pain for an average of 12.7 weeks.

It was found that those who had never received any previous care waited 7.3 weeks on the average, those who had been to a chiropractor previously waited 11.6 weeks, and those who had been to a physiotherapist earlier waited the longest at 13 weeks.

Discussion

In this survey, just over one-third (36%) of the patients claimed to have experienced pain since the “beginning of the pregnancy.” They presented in their second or third trimester (52% and 43%, respectively). Most commonly, they presented at 26 weeks of pregnancy and on average, had waited 11 weeks before they sought care. This puts a large number of the patients into a category of what would classically be termed chronic pain. Research has shown that over half of people with 3 or more months of pain, continue to have clinically significant back pain at 1 year. [1] Pregnancy itself is regarded as a risk factor for chronic back pain in women. [2] The length of time of pain before seeking care may perhaps have an influence on the course of the pain experienced after pregnancy. Many clinicians and patients accept back and pelvic pain as a normal side effect of pregnancy. Skaggs et al. [3] found that only 15% of the women with pregnancy related lumbo-pelvic pain received any care, only 10% of those were satisfied with the care given and most of the women in this study were not given any advice regarding available treatment options. Some women complained because they didn’t know there were options for treatment. A statement by a patient presenting to my office follows:“Why didn’t anyone refer me here earlier? It is just by chance I ended up here in this office. Had I known what I now know, I would have come much earlier.”

We need to know whether encouraging women to seek care early significantly decreases the length of pain episode and chronicity. Further long-term research is required to answer those questions.

Those patients who never had back pain previously waited the shortest amount of time before seeking treatment (average 4.5 weeks) and those with previous pelvic or back pain in pregnancy waited the longest (14 weeks). A reason why first time pain patients sought care earlier may have been that the pain was terrifying and they needed to know what was wrong with them, or it may reflect a changing attitude of the younger generation who do not have a “wait and see” approach to their problem. The authors hypothesize that it may reflect a healthy attitude of these women; they may want to know at an early stage what can be done for their condition, and how to prevent a progression of their problem.

Of those patients who had pain for more than 20 weeks before presenting to the chiropractor, all had experienced low back pain previously. The long wait could be due to them being less afraid of the pain (having experienced it before) and having learned to accept it, or having had previous treatment during earlier pregnancies that they perceived as being non-helpful. None of the patients whose first experience with back pain in her current pregnancy waited more than 20 weeks before seeking care. To have back pain for more than 20 weeks reflects the attitude of women with chronic pain; they “get used” to it and learn to live and deal with it and not complain about it.

Stevens [4] looked at “regular” chiropractic patients, whose average pain onset was three weeks before visiting the chiropractor was. This is two months earlier than this study. He found that one of the biggest barriers to seeking care was hope that the symptoms would go away. In the pregnant patient this may be true as well, as this is exactly what many patients in our study reported during their pregnancy. They would have sought care earlier, but were hoping that the pain would go away, only as the symptom worsened did they realize this was not the case. Others thought they could endure the pain because the end of the pregnancy was perceived to be close, but as the quality of life worsened they sought help for symptom relief. The authors hypothesized that the pain usually gets worse as the pregnancy progresses and the patient may, at some point, become desperate and decide to seek care. Another aspect of pregnancy pain is that it is often perceived as a “positive” pain, something good will come soon (the child) and there will probably be an end to the pain (the pregnancy will end).

For almost one-third (30%) of the patients in this study, chiropractic was their first choice of treatment, except visits to their medical doctor for routine checks. This may reflect a wider knowledge base of the patients, along with perhaps reflecting the growing status and position of chiropractic. In Norway perhaps this is a consequence of the law changes and privileges that chiropractors in Norway have been granted over the last few years. Chiropractors are primary care givers, have the right to write sick leave notes up to 12 weeks, have rights to prescribe physical therapy paid for by the government, as well as any kind of special testing such as radiographs, MRIs and further investigation by other specialists.

When reviewing these findings it is important to keep in mind the limitations of this particular study. As good as surveys can be at finding trends and locating gaps in information, the design of this study alone allows for many gaps in information. Due to the relatively small number of subjects (100 women) it is harder to draw conclusions and find trends than it would be with a larger population of subjects.

The patients presenting to this clinic may have unique characteristics from patients in other clinics, because it is a clinic specializing in pregnancy related problems. This clinic may also give an over representation of pelvic related pain, because the name of the clinic “bekken og barn”(pelvis and children”) reflects a condition and implies a focus on problems relating to the pelvic girdle. This could potentially leave out patients, for example, who have migraines in pregnancy as their chief complaint. The characteristics of these patients may also have been influenced by the relatively limited catchment area (limited geographic location) also affecting the socio-demographic profile.

As for the treatment, it was carried out by only one chiropractor, not giving room for differences from different practitioners in regards to number of treatments given, the areas of the spine treated, and the treatment schedules, even though these are not directly discussed in detail here. Thus, what is true for treatments given in this clinic may not reflect the practitioners in clinics that are not specializing in treating pregnant women. If there is indeed a difference in those who seek care from specialists, especially in regards to education and job satisfaction, this may also affect the sick leave statistics. Further research might elucidate whether those who seek specialized care are more satisfied with their job, and would want to try “everything” so they can stay working as long as possible. This may be especially true because they have to pay for their care out of their own pocket. In comparison, the most common alternative to a chiropractor is a physiotherapist, whose treatment in Norway is generally free of charge during pregnancy.

Conclusion

Some women seek chiropractic care during pregnancy and in this study, half were sent by health care practitioners. For one-third of the patients, chiropractic was their first choice for treatment. All had pain relating to the pelvic girdle or low back; however most of them had a combination of two or more pain sites. This study found that the longer the patient had pain before onset of care, the more pain sites they experienced, the more areas of the spine were treated and the more treatment they required. Future studies should concentrate on efficacy of treatment (as well as the initiation of early vs. delayed treatment), cost-effectiveness and prevention of chronicity of back pain that begins during pregnancy.

REFERENCES:

Dunn KM, Croft PR, Main CJ,Corf MV.

A prognostic approach to defining chronic pain: Replication in a UK primary care low back pain population.

Pain 2008; 135(1-2):48-54Gutke A, Ostgaard HC, Oberg B.

Predicting Persistent Pregnancy Related Low Back Pain.

Spine 2008; 33(12):386-393Skaggs CD, Prather H, Gross G, George JW, Thompson PA, Nelson DM.

Back and Pelvic Pain in an Underserved United States Pregnant Population:

A Preliminary Descriptive Survey

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007 (Feb); 30 (2): 130–134Stevens GL.

Behavioural and Access Barriers to Seeking Chiropractic Care: A study of 3 New York Clinics.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2007; 30:566-572

Return to PEDIATRICS

Since 12–24–2015

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |