Diagnosis and Chiropractic Treatment of Infant Headache

Based on Behavioral Presentation and Physical Findings:

A Retrospective Series of 13 CasesThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 (Oct); 32 (8): 682686 ~ FULL TEXT

Aurιlie M. Marchand, MChiro, DC, Joyce E. Miller, BS, DC, Candice Mitchell, MChiro

Private Practice,

Brussels, Belgium.

aureliemarchand@hotmail.com

OBJECTIVE: This case series presents information on diagnosis and treatment of 13 cases of benign infant headache presenting to a chiropractic teaching clinic.

CLINICAL FEATURES: A retrospective search was performed for files of infants presenting with probable headache revealing 13 cases of headache from 350 files.

INTERVENTION AND OUTCOMES: Thirteen cases (6 females, 7 males) from 2 days old to 8.5 months old were identified by behavioral presentation, parental, or medical diagnosis. In the cohort, historical findings included: birth trauma, assisted birth, familial headache history and feeding difficulty. Examination and behavioral findings were grabbing or holding of the face, ineffective latching, grimacing and positional discomfort, rapping head against the floor, photophobia and anorexia. Posterior joint restrictions of the cervical spine were found in these cases. No cases of malignant headache were found. All infants received a trial of chiropractic care including manual therapy.

CONCLUSION: This case series offers information about potential signs of benign infant headache. The patients in this study responded favorably to chiropractic management.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Background

Headache is the most frequently reported neurological symptom and a common cause of pain in children. [1] A large UK clinical study of schoolchildren reported migraine in 3.4% of 5-year olds and tension-type headache in 0.9% of 5- to 15-year olds. [2] In a population younger than 1 year, headaches have been reported with great variability, with only malignant headaches being mentioned.

There is a paucity of literature that describes a specific clinical approach to benign headache in infants. Information on incidence and etiology of pediatric headache might be extrapolated to infants until further evidence is gathered and published. The purpose of this study is to describe the findings and treatment of 13 infants with benign headache presenting to a chiropractic teaching clinic.

Methods

The cases were selected during a file audit of cases of infants who presented to the clinic over the last year. Files were previously labeled with the diagnosis and were easily located for review. Inclusion criteria were children less than 1 year of age who had presented with headache or had been diagnosed with headache. Data collection included demographic profile, familial history of headache, complaint, signs and symptoms, treatment or management plan, and outcome of care. A simple table was used to collect the data.

Patient management consisted of reassurance of the parents that the examination was void of any pathology. In the cases where a biomechanical diagnosis was made (in conjunction with headache), specialized low-force chiropractic manipulation was applied to the spinal areas where tension was found. The cervical spine was implicated in all cases. Outcomes were reported by the parents and were recorded verbatim.

The data collected were anonymous. All parents signed a form upon entering the clinic that the data of their child could be used for research purposes as long as it was held confidentially. All of these signatures were available for review at the time of the audit. Ethics approval for the file audit was granted by the project ethics subcommittee of Anglo-European College of Chiropractic.

Results

Table 1 Table 1 includes the details of 13 cases of infant headache with regards to age, gender, gestational age, birth weight, birth type, main complaint or symptoms, the signs, the chiropractic procedures used, and the results of therapy for each child.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this retrospective case series of 13 infants with suspected headaches is the largest presented on this topic in the chiropractic literature to date. Considering how common headache is in the older population, it is likely that infant headache is common, although under-reported. [3] Infant headache may simply not be routinely recorded, or may not be recognized by parents, unless they experience headache themselves. In one case, both parents had experienced common headaches and thus, may have recognized it in their infant. We found 13 cases of diagnosed headache in 350 infant cases for a rate of 3.7%. Four of these cases presented to the clinic with a complaint of headache for a rate of 1%. It is probable that headache in infancy is more common in our own practice because we diagnosed it based on signs and symptoms rather than exclusively on parental report.

We also diagnosed benign headache in the infant population whereas to our knowledge, only malignant headaches have been discussed in the literature in the infant population thus far. The conjecture of childhood headache is often met with attendant fear that it may be associated with serious illness. [3] In this series, none of the cases showed a progressive course and therefore, no further imaging or diagnostic testing was sought. If the general and neurological examinations are normal, the literature lends little support to the notion of routine neuroimaging. [4] Headache is a clinical diagnosis and there are rarely any further diagnostic investigations required. [3] Identifying risk factors for development of infant headache is an important step toward preventive interventions and management strategies. In adults, headache is often said to overlap with painful temporomandibular disorders (TMD). [5] It is thought that newborns frequently experience TMD relative to birth injury. [6] This may be a plausible mechanism of infant headache. Adults with TMD report increased headache upon wide opening of their mouth. [5] Capacious mouth opening is required in infants for feeding and this may be a precipitating factor for headache. In fact, headache associated with feeding was noted at the time of onset in 5 cases, just as teeth clenching is associated with headache in adults. [7] It is biologically plausible that parafunctional suck patterns could bring on headache in infants.

Another etiological factor could be neuromusculoskeletal irritation secondary to a difficult birth. Certainly head and neck injury increases the risk of chronic daily headaches in adults. [8] All of the children in this case series had experienced assisted births. Forces between 30 and 70 N have shown transient neurological effects when applied to the upper cervical spine in infants. [9] The forces exerted upon the cervical spine during assisted deliveries range from 77 to 199 N. [10, 11] These forces would likely be sufficient to cause muscular and mechanical joint impairments considering the increased laxity of infant spine. [12] Considering the prevalence of assisted births in this series of cases, it is plausible that, in some children, these impairments might result in pain in and about the head.

Most headaches were categorized as acute rather than chronic or recurrent. Two children appeared to have chronic tendencies, an 8-month old who had consistent head pain behaviors (head banging) and a 4-week old whose mother stated that the infant showed head pain behaviors 1/2 day per week. Research has shown that in 4 of 10 children with recurrent headache, the tendency is lifelong. [13] Therefore, these infant cases should be followed in the longer term.

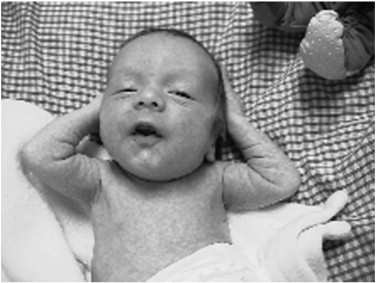

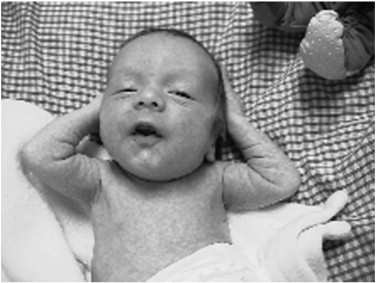

Figure 1

This figure represents a child holding his head, a behavioral pain indicator that may be present in infant headache.In this sample, specific types of headache were not established. However, in 2 cases, migraine was included in the differential diagnosis where both infants demonstrated pain behaviors, accompanied by holding their heads (Figure 1), hiding their eyes, turning to place their faces into a pillow, and refusing food. These were taken as signs of intense pain, anorexia and photophobia which are common symptoms of migraine. Half of children with migraine headache have a first degree relative with headache tendency. [3] This was documented in this small case series with one mother reporting migraine in both herself and the infant.

To our knowledge, this is the first time that a case series has been presented in the literature of benign infant headache treated by chiropractic therapy. A study described 6 cases of migraine headache in the infant and young child (age, 5-42 months). [14] All children were said to have a strong family medical history of migraine presenting with features including pallor, irritability, sleep disturbance, mood changes, ptosis, head pain, emesis/abdominal pain, head banging, eyes dilating. This was not a chiropractic study as all children were treated with either amitriptyline or imipramine in low doses.

Limitations

This study has all of the weaknesses inherent in a retrospective case report. First, we gathered the data retrospectively and relied on case reports made at the time of the initial presentation; we were unable to go back and ask more pertinent questions to be more certain of the diagnosis (for example, the extent and location of contusion following birth trauma). We were able to collect only the data which were recorded.

Data relied on parental report (which may have suffered from recall bias) rather than the more reliable hospital records for the birth history. In addition, the study does not include those who had less obvious signs of headache but still may have suffered from headache but were not diagnosed.

An inherent limitation is that none of the patients were able to speak for themselves and we had to rely on observation of the parent and the clinician. It is possible that potential bias toward the diagnosis of headache took place and that none of the children had headache but some other type of pain syndromes they were unable to express.

Examinations were performed by several clinicians so the findings may not have been standardized. We have relied on extrapolation from literature documenting headaches in the older child for further explanations and it is unknown whether this extrapolation is appropriate to the infant population.

With respect to management of the patient, as with any clinical study, resolution of clinical indicators may be part of the natural resolution of symptoms rather than the treatment itself.

Conclusion

In the absence of any red flags, this case series suggests that signs and symptoms of headache occur in infancy and a therapeutic trial of chiropractic care may be a reasonable clinical approach to infant headache.

Practical Applications

Birth trauma, assisted birth, familial headache history and feeding difficulty were historical factors.

Grabbing or holding of the face, ineffective latching, grimacing and positional discomfort, rapping head

against the floor, photophobia and anorexia were found in the examination.

References:

Goodman, JE and McGrath, PJ.

The epidemiology of pain in children and adolescents: a review.

Pain. 1991; 46: 247264Abu-Arefeh, I and Russell, G.

Prevalence of headache and migraine in schoolchildren.

BMJ. 1994; 309: 765769Newton, RW.

Childhood headache.

Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2008; 93: 105111Lewis, DW.

Practice parameter: Evaluation of children and adolescents with recurrent headaches:

report of Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and Practice Committee

of the Child Neurology Society.

Neurology. 2002; 59: 490498Glaros, AG, Urban, D, and Locke, J.

Headache and temporomandibular disorders: evidence for diagnostic and behavioral overlap.

Cephalgia. 2007; 27: 542549Wall, V and Glass, R.

Mandibular asymmetry and breastfeeding problems: Experience from 11 cases.

J Hum Lact. 2006; 22: 328334Glaros, AG and Burton, E.

Parafunctional clenching, pain and effort in temporomandibular disorders.

J Behav Med. 2004; 27: 91100Couch, JR, Lipton, RB, Setwart, WF, and Scher, AI.

Head or neck injury increases the risk of chronic daily headache.

Neurology. 2007; 69: 11691177Koch, LE, Koch, H, Graumann-Brunt, S, Stolle, D, Ramirez, JM, and Saternus, KS.

Heart rate changes in response to mild mechanical irritation of the high cervical spinal cord region in infants.

Forensic Sci Int. 2002; 128: 168176Hughes, CA, Harley, EH, Milmoe, G, Bala, R, and Martorella, A. 1999.

Birth trauma in the head and neck.

Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999; 125: 193199Laufe, LE.

Crossed versus divergent obstetric forceps.

Obstet Gynecol. 1969; 34: 853858Owenbach, RK and Menezes, AH.

Spinal cord injury without radiographic anbnormality in children.

Pediatr Neurosci. 1989; 15: 168175Dignan, F, Symon, DNK, and Abu-Arafeh, I.

The prognosis of cyclical vomiting syndrome.

Arch Dis Child. 2001; 84: 5557Elser, JM and Woody, RC.

Migraine headache in the infant and young child.

Headache. 1990; 30: 366368

Return to HEADACHE

Return to PEDIATRICS

Since 3-22-2019

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |