Injuries in the Pediatric Patient:

Review of Key Acquired and Developmental IssuesThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Clinical Chiropractic Pediatrics 2009 (Dec); 10 (2): 665—670 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Beverly L. Harger, D.C., D.A.C.B.R., and Kim Mullen, D.C.

Department of Radiology,

Western States Chiropractic College,

Portland, OregonKey words: pediatric trauma, growth plate fractures, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, incomplete fractures, torus fracture, spondylolysis, pars interarcularis defects, single photon emission computed tomography, Scheuermann’s disease, ring apophyseal fracture.

Introduction

A plethora of conditions specifically target children and adolescents which are not prevalent in the adult population. Understanding the age-related differences in this population can help clinicians improve diagnosis and therefore management of these conditions. Though it is beyond the scope of this paper to extensively address diseases targeting the pediatric population, common key injuries will be discussed with emphasis on the role imaging plays in establishing accurate diagnosis.

Obesity and the musculoskeletal system

Table 1

Table 2

Table 3

Table 4

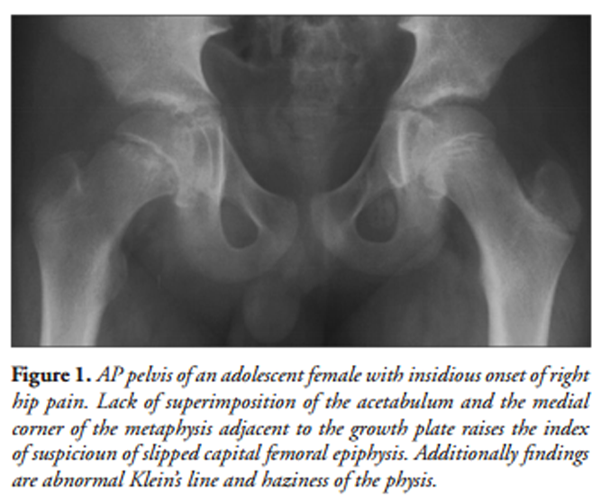

Figure 1

Figure 2 An alarming statistic in the United States is the prevalence of obesity, defined as mean Body Mass Index (BMI) greater than 95th percentile, being reported as approximately 17% in children and adolescents. [1-3] The reason for this is most likely multifactorial. Lack of physical activity, increase in caloric intake and environmental factors are all potential contributors. [2] Addressing the underlying cause of obesity in a child or an adolescent is paramount. Additionally, an important role of chiropractic clinicians is to anticipate how obesity may affect the musculoskeletal system. Several key comorbid conditions are commonly reported: slipped capital femoral epiphysis, Blount’s disease and genu varum, genu valgum, increased musculoskeletal pain, increase risk of fracture, impact on gait and function, and arthritis are most commonly reported. [2] (Table 1)

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis

As the most common orthopedic hip condition affecting adolescents it is imperative that chiropractic physicians are aware of the clinical manifestations, establish early diagnosis, facilitate best treatment and participate in postoperative care of patients with slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE). (Table 2) Chiropractors play a vital role in each step of the management of adolescents with this condition. The incidence rate has been reported as 10.80/100,000 with boys being 13.5 and girls 8.0. [4] When compared to whites, SCFE was found to be four times as prevalent in blacks and over two and one half times as prevalent in Hispanics. [4] The best prognosis correlates with early diagnosis. A thorough knowledge of etiology, clinical manifestations and classification, imaging protocol and radiologic findings is essential. As mentioned previously, this disease appears to be more common in obese adolescents and is thought to increase a shear stress across the physis. Other etiologic factors such as local trauma, inflammatory and endocrinological factors, and previous radiation are reported. [5, 6] (Table 3)

Critical to proper management is an understanding of the classification of slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE). A common classification system is currently used to identify a stable versus unstable SCFE. [5] (Table 4) An adolescent that is unable to bear weight on the affected leg, limps in external rotation and experiences pain with any hip motion most likely has an unstable SCFE. [5] Caution should be taken when imaging these patients with an AP pelvis view usually sufficient to demonstrate the slippage. With unstable slips, the patient is at increased risk for development of avascular necrosis, necessitating emergent orthopedic referral with hospitalization. [5] In our ambulatory care clinics, patients with stable SCFE are more commonly encountered than patients with unstable SCFE. Establishing diagnosis in these patients can be challenging and special attention needs to be given to the proper imaging protocol. Knowledge of the subtle radiographic is of critical importance.

Radiographic evaluation in a patient with a suspected stable SCFE should include bilateral AP and bilateral frogleg lateral views since up to 60% of patients have bilateral slips at the time of diagnosis. [5] Key radiographic findings include an abnormal Klein’s line, haziness of the physis and relative loss of height of the epiphysis. On the AP view only, the lack of superimposition of the acetabulum with the medial corner of the metaphysis that is adjacent to the physis strongly suggests SCFE. (Figure 1) If this finding is present on the AP view, the clinician should carefully evaluate the frog-leg lateral view for other radiographic evidence. The frog-leg lateral view is the most sensitive for detecting subtle slippage. (Figure 2)

Editor's Comment: Pinkowsky reports in their 2013 study that relying on Klein's Line

will fail to identify many mild or moderate slips. They also stated:“Of the 23 hips studied with slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), only 9 (39%) were able to be diagnosed on the AP radiograph using the classic definition of the Klein line. Twenty cases (87%) of SCFE were identified on the AP radiograph using the modified Klein line. All 23 cases (100%) of SCFE were identified on frog lateral radiographs.”

Klein line on the anteroposterior radiograph is not a sensitive diagnostic radiologic test

for slipped capital femoral epiphysis

J Pediatr. 2013 (Apr); 162 (4): 804-7A general rule for clinicians to remember is that the earlier the SCFE is identified, the better the prognosis. If not treated in its early stages there is a high morbidity including loss of hip motion, pain, arthritis, avascular necrosis and chondrolysis. (Table 4) If the clinician has a strong index of suspicion of SCFE in a patient with negative plain films, magnetic resonance imaging should be ordered. In the presence of a unilateral slippage, the patient should be monitored for at least one year since there is a 25% to 40% incidence of developing a contralateral SCFE. [6]

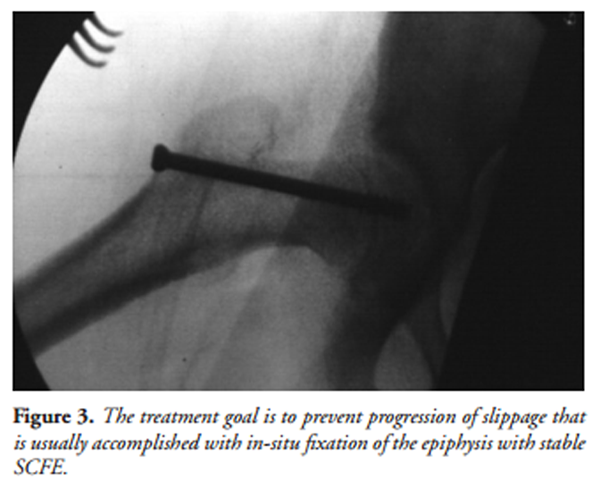

Figure 3 The treatment goal for SCFE is to prevent progression and slippage with in-situ fixation of the epiphysis with pins or a screw. (Figure 3) This procedure allows for immediate weight-bearing by the patient, has low further slippage rate, and helps prevents complications. Surgical follow-up in these patients occurs at 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year. Clinicians should encourage patients to adhere to a closely monitored treatment plan during this time.

Kids don’t sprain, they break

A helpful maxim to remember when dealing with child or adolescent trauma is “Kids don’t sprain, they break”. This reminds the clinician to carefully scrutinize radiographs for fractures unique to this population such as incomplete and growth plate. Typically in our offices we evaluate pediatric patients who have sustained a low-velocity injury such as a fall. Many of these fractures are easily managed through close reduction and casting for a short period of time and normal function is restored. As a general rule, fractures in children heal twice as fast as fractures in the mature skeleton. The periosteum in the child is thick with excellent osteogenic capabilities allowing creation of a stable union with less potential for displacement as compared to the adult. [7] Non-unions are rare in the pediatric population.

Skeletal trauma as a sign of abuse. Being cognizant of the signs that suggest a more serious situation, however, is vital. Skeletal trauma is the second most common manifestation of abuse. A telltale sign of non-accidental trauma in a young child is the classic metaphyseal lesion (CML) which most frequently involves the distal femur, proximal and distal tibia, and proximal humerus. [8, 9] The CML represent microfractures that cross the metaphysis with the fracture line parallel to the physis and perpendicular to the long axis of the involved bone. Generally the thicker peripheral rim is more visible and when viewed in profile appears as a triangular fracture known as a corner fracture. The mechanism of injury is due to horizontal shear force across the metaphysis as a result of violent holding and shaking of an infant by the feet or hands. [8] It is unusual to see this injury in a child over 18 months. Additionally, any fracture in a nonambulatory child should raise suspicion of child abuse. In a study by King et al, the majority of abusive fractures were in the long bones. [8, 9] Key fractures that should raise suspicion of abused children are the classic metaphyseal lesion as discussed earlier, scapulae fractures, spinous process fractures, sternal fractures and first rib fractures. [9] The first rib fracture is considered diagnostic of non-accidental trauma. [9]

Growth plate fractures

Clinicians should be aware that fractures through the growth plate can be difficult to interpret in the absence of displacement. Anticipating growth plate fractures will increase level of suspicion of subtle findings on plain film radiographs and hopefully improve diagnosis. If these fractures are not recognized growth plate disturbances such as progressive angular deformity, limb-length discrepancy, or joint incongruity may result. Growth plate fractures represent 15% of all pediatric fractures and almost all lead to growth arrest with the exception of the distal radius. [10] Distal femur and proximal tibia, although infrequent sites, carry a high incidence of post-traumatic premature fusion and should be carefully monitored for these complications. [10]

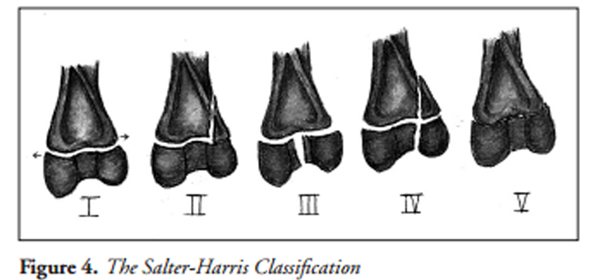

Figure 4

See also

RadioPedia.org

Figure 5

Figure 6

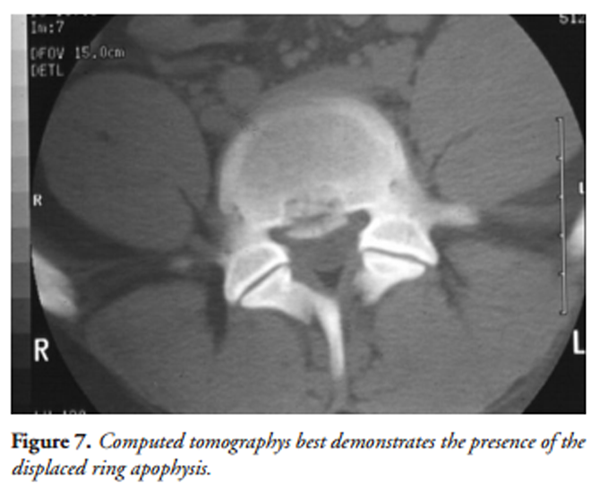

Figure 7 The Salter-Harris Classification is typically used to report these fractures. (Figure 4)

In addition to physeal fractures at the ends of the long bones, apophyseal regions are also vulnerable to injury in pediatric population. A mimicker to be aware of when assessing the pediatric foot is the apophysis of the fifth metatarsal. The normal appearance of the fifth metatarsal apophysis runs parallel with the long axis of the fifth metatarsal and should not be misinterpreted as fracture. (Figure 5) The pelvis region is particularly vulnerable in young athletes. Clinicians should be aware of potential for injury at the ischial tuberosity, anterior inferior iliac spine, anterior superior iliac spine and iliac crest. (Figure 6)

Analogous to the growth plate of the long bone is the ring apophysis of the vertebral body. A weak region exists between the ring apophysis and the vertebral body where displacement may occur. The imaging modality that best demonstrates the presence of the displaced ring apophysis is computed tomography. (Figure 7) Fractures at these sites are often accompanied by disc herniation. An adolescent patient with a disc herniation associated with ring apophysis fracture generally has more severe pain and radiculopathy. [11]

Imaging of traumatic causes of back pain in adolescent athletes

Common conditions to cause back pain in adolescent athletes include spondylolysis with or without spondylolisthesis, intervertebral disc herniation and the aforementioned vertebral apophyseal fracture. Selection of the proper imaging modality will improve diagnosis of these conditions. The first imaging modality typically selected in the adolescent athlete with back pain is plain film; however, understanding the limitations of this modality is critical. Pars interarticularis fractures without associated spondylolisthesis, stress reactions of the pars interarticularis regions, intervertebral disc lesions and vertebral body endplate fractures can be overlooked with plain film imaging.

If the clinician’s index of suspicion is high for acute pars interarticularis fracture, single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) is recommended. The thin-cut CT slices with SPECT imaging improve the visualization of a stress reaction or stress fracture of the pars interarticularis region and directs the clinician in determining if immobilization with a goal of healing the injury is needed. [12, 13] Clinicians should also be aware that a normal plain film and SPECT does not rule out the possibility of serious underlying pathology. Magnetic resonance imaging has been shown to be of value in the depiction of serious occult disease processes. [14, 15] Another limitation of plain film radiography is its difficulty in providing direct visualization of significant intervertebral disc lesions including intraosseous disc herniations (Schmorl’s node). These lesions are best depicted with magnetic resonance imaging. As mentioned previously, associated vertebral apophyseal fractures are best imaged with computed tomography.

Diseases related to growth disturbances

A potential source of confusion for clinicians when evaluating back pain in a pediatric patient is a lumbar variant of Scheuermann’s disease. Back pain has been reported to be present in 20% to 30% of adolescents with this condition. [13] The classic radiographic presentation of Scheuermann’s disease includes >5 degrees of anterior wedging in at least three adjacent vertebrae along with one associated sign. [13] These associated findings include Schmorl’s nodes, irregularity and flattening of vertebral endplates, narrowing of intervertebral discs, and antero-posterior elongation of apical vertebral bodies. [16] Unlike the classic Scheuermann’s disease, the lumbar variant may affect a single level with the vertebral wedging usually less severe. These patients are more likely to be symptomatic and are more likely to have progression into adulthood. [2]

Conclusion

As mentioned throughout this article, it is imperative that clinicians have thorough knowledge of musculoskeletal injuries that target the pediatric population. Carrying a high index of suspicion, improving interpretation skills and ordering the most appropriate imaging modality will further improve recognition of these conditions resulting in proper management and a decrease in complications and comorbidities known to be associated with these injuries.

REFERENCES:

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, et al.

Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2002.

JAMA 2006; 295:1549-1555Chan G, Chen CT.

Musculoskeletal effects of obesity.

Current Opinion in Pediatrics 2009; 21:65-70Hedley AA, Ogden CL, Johnson CL, et al.

Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999-2002.

JAMA 2004; 291:2847-2850Lehman CL, Arons RR, Loder RT, et al.

The Epidemiology of Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis: An Update.

Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics 2006; 26(3):286-290Gholve PA, Cameron DB, Millis MB.

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis update.

Current Opinion in Pediatrics 2009; 21:39-45Hart ES, Grottkau BE, Albright MB.

Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis: Don’t Miss This Pediatric Hip Disorder.

The Nurse Practitioner 2007; 32(3):14-21.Rodriguez-Merchan EC.

Pediatric Skeletal Trauma.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 2005; 432:8-13.Kleinman PK, Marks S, Blackbourne B.

The metaphyseal lesion in abused infants: a radiologic-histopathologic study.

Am J Roentgenol 1986, 146:895-905.Tenney-Soeiro R, Wilson C.

An update on child abuse and neglect.

Current Opinion in Pediatrics 2004, 16:233-237.Ecklund K.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Pediatric Musculoskeletal Trauma.

Topics in Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2002; 13(4):203-218.Chang CH, Lee ZL, Chen WJ, Tan CF, Chen LH.

Clinical Significance of Ring Apophysis Fracture in Adolescent Lumbar Disc Herniation.

Spine 2008; 33(16):1750-1754.Bellah RD, Summerville DA, Treves St, et al.

Low-back pain in adolescent athletes: detection of stress injury to the pars interarticularis with SPECT.

Musculoskeletal Radiology 1991; 180:509-512.Khoury NJ, Hourani MH, Arabi MMS, Abi-Fakher F, et al.

Imaging of Back Pain in Children and Adolescents.

Current Problems in Diagnostic Radiology 2006; 35:224-244.Davis PC, Hoffman JC, Ball TI, et al.

Spinal abnormalities in pediatric patients: MR imaging findings compared with clinical myelographic, and surgical findings.

Radiology 1988; 166:679-685.Feldman DS, Hedden DM, Wright JG.

The Use of Bone Scan to Investigate Back Pain in Children and Adolescents.

Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics 2000; 20:790-795.Lowe TG.

Scheuermann’s disease.

Orthop Clin North Am 1999; 30:475-487.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, et al.

Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2002.

JAMA 2006; 295:1549-1555.Chan G, Chen CT.

Musculoskeletal effects of obesity.

Current Opinion in Pediatrics 2009; 21:65-70.Hedley AA, Ogden CL, Johnson CL, et al.

Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999-2002.

JAMA 2004; 291:2847-2850.Lehman CL, Arons RR, Loder RT, et al.

The Epidemiology of Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis: An Update.

Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics 2006; 26(3):286-290.Gholve PA, Cameron DB, Millis MB.

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis update.

Current Opinion in Pediatrics 2009; 21:39-45Hart ES, Grottkau BE, Albright MB.

Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis: Don’t Miss This Pediatric Hip Disorder.

The Nurse Practitioner 2007; 32(3):14-21.Rodriguez-Merchan EC.

Pediatric Skeletal Trauma.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 2005; 432:8-13.Kleinman PK, Marks S, Blackbourne B.

The metaphyseal lesion in abused infants: a radiologic-histopathologic study.

Am J Roentgenol 1986, 146:895-905.Tenney-Soeiro R, Wilson C.

An update on child abuse and neglect.

Current Opinion in Pediatrics 2004, 16:233-237Ecklund K.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Pediatric Musculoskeletal Trauma.

Topics in Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2002; 13(4):203-218.Chang CH, Lee ZL, Chen WJ, Tan CF, Chen LH.

Clinical Significance of Ring Apophysis Fracture in Adolescent Lumbar Disc Herniation.

Spine 2008; 33(16):1750-1754.Bellah RD, Summerville DA, Treves St, et al.

Low-back pain in adolescent athletes: detection of stress injury to the pars interarticularis with SPECT.

Musculoskeletal Radiology 1991; 180:509-512.Khoury NJ, Hourani MH, Arabi MMS, Abi-Fakher F, et al.

Imaging of Back Pain in Children and Adolescents.

Current Problems in Diagnostic Radiology 2006; 35:224-244.Davis PC, Hoffman JC, Ball TI, et al.

Spinal abnormalities in pediatric patients: MR imaging findings compared with clinical myelographic, and surgical findings.

Radiology 1988; 166:679-685.Feldman DS, Hedden DM, Wright JG.

The Use of Bone Scan to Investigate Back Pain in Children and Adolescents.

Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics 2000; 20:790-795.Lowe TG.

Scheuermann’s disease.

Orthop Clin North Am 1999; 30:475-487

Return to RADIOLOGY

Return to PEDIATRICS

Since 12-25-2015

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |