Assessing the Impact of Headaches and the Outcomes of

Treatment: A Systematic Review of Patient-reported

Outcome Measures (PROMs)This section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Cephalalgia 2018 (Jun); 38 (7): 1374–1386 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Kirstie L Haywood, Tom S Mars, Rachel Potter, Shilpa Patel, Manjit Matharu, Martin Underwood

Warwick Research in Nursing,

Department of Health Sciences,

Warwick Medical School,

The University of Warwick,

Gibbet Hill, Coventry, UK.

Aims: To critically appraise, compare and synthesise the quality and acceptability of multi-item patient reported outcome measures for adults with chronic or episodic headache.

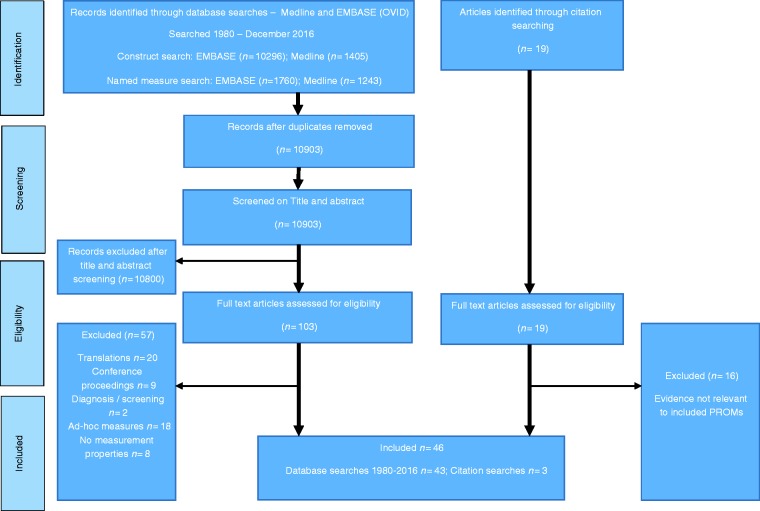

Methods: Systematic literature searches of major databases (1980–2016) to identify published evidence of PROM measurement and practical properties. Data on study quality (COSMIN), measurement and practical properties per measure were extracted and assessed against accepted standards to inform an evidence synthesis.

Results: From 10,903 reviewed abstracts, 103 articles were assessed in full; 46 provided evidence for 23 PROMs: Eleven specific to the health-related impact of migraine (n = 5) or headache (n = 6); six assessed migraine-specific treatment response/satisfaction; six were generic measures.

Evidence for measurement validity and score interpretation

was strongest for two measures of impact,Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (MSQ v2.1) and

Headache Impact Test 6-item (HIT-6),and one of treatment response, the

Patient Perception of Migraine Questionnaire (PPMQ-R).

Evidence of reliability was limited, but acceptable for the HIT-6. Responsiveness was rarely evaluated.

Evidence for the remaining measures was limited.

Patient involvement was limited and poorly reported.

Conclusion: While evidence is limited, three measures have acceptable evidence of reliability and validity: HIT-6, MSQ v2.1 and PPMQ-R.

Only the HIT-6 has acceptable evidence supporting its completion by all “headache” populations.

Keywords: Headache; patient-reported outcome; reliability; systematic review; validity.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Background

Headache disorders are common in the adult population; the most common – tension-type and migraine – have a one-year prevalence of 40% and 11% respectively. [1–3] Between 2–4% of the general population experience chronic headache. [4, 5] Headache disorders can profoundly impact an individual’s functional ability and quality of life. [3, 6] Affecting primarily young adults, the personal and economic burden of headache is substantial and comparable to other chronic conditions such as congestive heart failure, hypertension, or diabetes. [7]

An individual’s self-report of the presence, severity, frequency, and impact of headache is crucial to understanding the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), which seek to provide a patient-based assessment of the impact of headache on how people feel, function and live their lives, are now available. While recommendations to include PROMs in headache clinical trials are available [8, 9], specific guidance for PROM-based outcome reporting does not exist. The integrity of PROM-based reporting is underpinned by clear evidence of essential measurement and practical properties in the clinical population of interest. [10, 11] It cannot be assumed that the reliability and validity of measure is consistent across different types of headache, and evidence of PROM performance across different sub-types is often not available. [12] PROM score interpretation also requires guidance for what change in score reflects a meaningful change in “headache” for the individual patient (minimal important change (MIC)) and what difference reflects a meaningful difference between groups of patients defined by some external anchor (minimal important difference (MID). [10, 11] Structured reviews of PROM performance provide essential evidence to inform the selection of robust, relevant, and acceptable measures.

In this systematic review, we critically appraise, compare and synthesise published evidence of essential measurement and practical properties for clearly defined PROMs evaluated in adult headache populations. The review provides a transparent summary of the evidence base with which to inform PROM selection for future application in headache-specific research.

Methods

Identification of studies and PROMs: Search strategy

The search strategy was developed by experienced reviewers (KH, TM, RP, SP) and with expert librarian support to retrieve references relating to the development and/or evaluation of multi-item PROMs used in the assessment of adults (aged 18 years and above) with chronic or episodic headache including migraine.

Medical subject headings (MeSH terms) and free text searching were used to reflect three characteristics: a) population – headache and migraine; b) type of assessment – patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs); and c) measurement and practical properties. [11, 13, 14] The full search strategy is available in Appendix 1.1.

Figure 1 Two databases were searched (MEDLINE (OVID), EMBASE (OVID); 1980 to December 2016) (Figure 1). A subsequent search incorporated the names of more than 50 multi- and single-item measures identified during the initial search (Appendix 1.2 and 1.3). From a total of 39 multi-item PROMs thus identified, 16 had been superseded by revised measures or were no longer in use, as evidenced by their lack of inclusion in studies published post 2000 (Appendix 2). Given that such measures are unlikely to be of interest, the eligibility criteria for the review and analysis was revised to focus on PROMs in use post–2000.

The citation lists of included articles and existing reviews were also reviewed (15,16). Named author searches were conducted.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Titles and abstracts of all articles were independently assessed for inclusion/exclusion by two reviewers (TM, KH) and agreement checked. Published articles were included if they provided evidence of development/evaluation for clearly defined, reproducible, multi-item PROMs, following self-completion by adults who self-reported or had been diagnosed by a clinician as having a headache disorder. Articles relating solely to the application of measures without some evidence of measurement and/or practical properties were excluded. Articles describing the translation of PROMs and/or evaluations in non-English speaking populations were also excluded. Conference papers and abs

tracts were excluded. Included PROMs had to be in use in research published between 2000–2016. PROMs were categorised as: Generic (profile; utility) or condition-specific (headache; migraine). Clinician-reported, diagnostic and screening measures were excluded. Domain-specific measures that were not specific to the impact of headache, and measures that were not clearly reproducible, were excluded.

Data extraction and appraisal

A data extraction form was informed by guidance for PROM evaluation [10, 11, 17], published PROM reviews [14, 18, 19] and the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) checklist. [20, 21] The form captured both study and PROM-specific information. Population diagnosis and diagnostic criteria (if any) were extracted. We sought evidence on: Reliability (internal consistency; test–retest, intra/inter-tester); validity (content; construct; known groups); responsiveness; interpretation (minimal important change (MIC) and/or difference (MID)); and precision (data quality; end effects). Evidence for the practical properties included acceptability (relevance; respondent burden) and feasibility. Evidence of active patient involvement in PROM evaluation was also sought. [18, 22, 23 ] All publications were double-assessed (KH, TM) and agreement checked.

Assessment of study methodological quality

One experienced reviewer (KH) applied the COSMIN checklist to assess the methodological quality of included studies. [20, 21] Methodological quality was evaluated per measurement property on a four-point rating scale (excellent, good, fair, poor) and determined by the lowest rating of any items in each checklist section. [21]

Assessment of PROM quality

A similar checklist for PROM quality does not exist. Therefore, a pragmatic checklist informed by a synthesis of various recommendations was adopted [18, 19, 21, 24] (Appendix 3: Table 2). To provide a global overview of the concepts captured within the reviewed headache-specific measures, items were categorised as per the domains of one of the most frequently used conceptual models of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) – the Ferrans revision to the Wilson and Cleary model. [25, 26]

Data synthesis

A qualitative synthesis of evidence per reviewed PROM per reported measurement property informed the overall judgement of quality and acceptability. The synthesis combined four factors: a) study methodological quality (COSMIN scores); b) number of studies reporting evidence per PROM; c) results per measurement property (Appendix 3: Table 2); and d) evidence of consistency between evaluations. [23, 27] Two elements of the data synthesis are described: First, the overall quality of a measurement property was reported as adequate (+), conflicting (±), inadequate (–), or indeterminate (?). Second, evidence for the overall quality of evidence was categorised as “strong”, “moderate”, “limited”, “conflicting”, or “unknown”. [27]

Results

Identification of studies and PROMs

Study and PROM identification is summarised per PRISMA guidance in Figure 1 (www.prisma-statement.org). Forty-six articles provided evaluative evidence for 23 PROMs (Appendices 4 and 5 (Tables 3 and 4)).

Six assessed impact of headaches overall:

The EUROLIGHT [28];

Headache Activities of Daily Living Index (HADLI) [29];

Headache-specific Disability Questionnaire (HDQ) [30];

the Headache Impact Test (HIT) [3] and

its short-form HIT-6 [31];

and a headache-specific modification of the Short-Form 36-item Health Survey. [32]Five were specific to the impact of migraine:

Functional Assessment in Migraine questionnaire (FAIM) [33];

Headache Needs Assessment Survey (HANA) [34];

MIgraine Disability ASessment (MIDAS) [35];

Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (MSQ v2.1) [36]; and

the Migraine-Specific Quality of Life (MSQOL) measure. [37]Six assessed response to and/or satisfaction with migraine-specific drug treatment:

Completeness of Response to migraine therapy (CORS) [38];

Migraine Assessment of Current Therapy (Migraine-ACT) [39];

Migraine-Treatment Assessment Questionnaire (M-TAQ) [40];

Migraine-Treatment Optimisation Questionnaire (M-TOQ) [41];

Migraine Treatment Satisfaction Measure (MTSM) [42]; and

the Patient Perception of Migraine Questionnaire – Revised (PPMQ-R). [43]

Item content of all specific measures is illustrated in Appendix 6 (Table 5).Finally, six generic measures had been assessed in headache populations:

The Short-Form 36-item Health Survey (SF-36) [44],

SF-12 [45],

SF-8 [46],

EuroQoL EQ-5D 3L [47],

Health Utility Index-3 (HUI-3) [48] and

the Quality of Well-being Scale (QWB). [49, 50]

Patient and study characteristics (Appendix 5 (Table 4) )

Patient populations ranged from 18 to 83 years, were largely white, often with large proportions of female participants. Sample sizes ranged from 25 to more than 8,500. Populations included mixed, chronic, and/or episodic headache or migraine. Where clinician-based diagnosis was described, most adopted the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-II), available at http://www.ihs-klassifikation.de/en/. However, for many, patients were self-diagnosed, and a wide range of diagnostic criteria were described. Most studies were cross-sectional or longitudinal surveys. Nine were clinical trials or involving data secondary analysis. Fourteen studies were specific to PROM development and/or initial evaluations. Most evaluations were with US populations.

Measurement properties and methodological quality

Table 1

p. 5+6Study methodological quality per measurement property per reviewed PROM is presented in Appendix 7 (Table 6). The overall evidence synthesis is presented in Table 1.

PROMs assessing migraine and headache-specific impact (n = 11)

Apart from the FAIM, MSQ v2.1, MSQoL and HIT, all measures lack a clear description of aim, the concepts being measured, or the process of item generation. The FAIM [33], MSQ v2.1 [36] and MSQoL [37] involved expert clinicians and patients in item generation, supporting a positive rating of content validity.

The HIT “item bank” was informed by four legacy measures – the MIDAS, MSQ (v1.0), Headache Disability Index (HDI) and Headache Impact Questionnaire (HIMQ) – and consultation with clinicians. [3] Apart from the MSQ, item generation for these measures is poorly reported but largely driven by clinical opinion. Additional evaluations of the content validity of the item bank or short form measures is not described. Clinical opinion, literature review, and/or the completion of established questionnaires were the main sources of items for the remaining measures. There was no evidence of active patient collaboration in PROM development and/or evaluation.

The shortest measures are the MIDAS (five items) and HIT-6 (six items); the longest is the 103–item EUROLIGHT (Table 2). Apart from the FAIM, all assess headache/migraine symptomology. While five headache-specific measures assess pain, the migraine-specific measures do not. Only the HANA, MSQv2.1 and HIT-6 assess fatigue.

All assess the impact of headache/migraine on social function, activities of daily living and/or work. Seven – FAIM, HANA, MSQv2.1, MSQOL, HIT, HIT-6, and EUROLIGHT – assess the emotional burden of headache/migraine; five of these – FAIM, MSQv2.1, HIT, HIT-6, and EUROLIGHT – plus the HADLI, assess the impact on cognition and difficulty with thinking.

Acceptable evidence of measurement dimensionality from studies of at least moderate methodological quality was reviewed for five measures –FAIM [33],

MSQv2.1 [12, 21],

MSQoL [52],

HIT [3],

HIT-6 [53];three have moderate to strong evidence of both structural validity and internal consistency –

FAIM [33],

MSQ v2.1 [12, 36, 51, 54] and

the HIT-6 [31, 41, 53, 55, 56] (Table 1; Appendix 7).Three measures have acceptable evidence of the reliability of internal consistency from studies of at least moderate methodological quality, supporting application in the assessment of groups

groups (FAIM) [33] and

individuals (MSQ v2.1 [12, 36, 51],

groups HIT-6 [53, 56]) (Table 1; Appendix 7);however, for the majority, evidence was limited (n = 3), from poor quality studies (n = 3) or not available (n = 1).

Only the HIT [31, 57] and HIT-6 [31, 53, 56, 57] have acceptable evidence of temporal stability supporting application in the assessment of groups and individuals.

Evidence for the remaining measures was limited.

Five measures have acceptable evidence from good quality studies describing their construct validity –FAIM [33],

MIDAS [56],

MSQ v2.1 [12, 36, 43, 53],

HIT [57] and

HIT-6 [12, 53, 56, 57].For the remaining measures, evidence was of poor quality (n = 4) or not available (n = 2); authors often failed to hypothesise a priori the association between variables.

Evidence of responsiveness was limited. Statistically significant between-group differences for average HIT-6 and total HIT change scores were reported for patients categorised by self-reported change (better/same/worse) in physical activity, level of frustration or daily activities following a three-month follow-up period of “usual care”. [31]

Large and moderate effect size statistics were reported for the MSQv2.1 [12] and HIT-6 [53] in patients who reported large or moderate improvement in the number of headache days following a pharmaceutical-based clinical trial, respectively. Following a non-comparative, observational study of zolmitriptan for an acute migraine attack, small and moderate ES statistics were reported for the SF-36 and MSQoL respectively. [52]

Following completion of the HIT-6 by patients with chronic daily headache in a trial of usual medical care (UMC) versus UMC plus acupuncture, an anchor-based estimate of the MIC was calculated as approximately 3.7; the MID was estimated as 2.3. [58] Change in HIT-6 scores that exceeded the proposed MIC were reported in patients with chronic migraine receiving onabotulinumtoxinA in a placebo-controlled double blind trial; a between-group difference that exceeded the MID, in favour of the active treatment, was also reported. [59]

Both anchor-based [60, 61] and distribution-based estimates [60] were calculated for the MSQv2.1 following completion by patients with chronic migraine. Cole et al. [60] proposed an MIC of 5.0 for the RR domain, with ranges for the RP (5.0 to 7.9) and EF (range 8.0 to 10.6) domains; MIDs were recommended as RR 3.2, RP 4.6, EF 7.5. [60] A between-group difference that exceeded the proposed MID, in favour of the active treatment, was reported for the MSQv2.1 RR domain only in patients with chronic migraine receiving onabotulinumtoxinA in a placebo-controlled double blind trial. [59] However, within-individual change scores were larger than the proposed MIC for each domain for patients receiving active treatment.

PROMs assessing response to or satisfaction with migraine-specific treatment (six measures)

Four of the six measures – the CORS, M-TOQ, MTSM and PPMQ-R – have acceptable descriptions of the measurement aim, conceptual underpinning and item generation.

Although detail is limited, three measures – CORS, MTSM and PPMQ-R – involved both expert clinicians and patients in item generation (the MTSM involved US and UK participants), supporting a positive rating of content validity; the M-TAQ utilised patient interviews and focus groups, with additional reference to established treatment optimisation measures.

Item generation for the M-ACT [39] and the M-TOQ [41] was informed by clinical evidence and the consensus of clinical headache experts and researchers; patients were not involved, supporting a negative rating of content validity. There was no evidence of active patient collaboration.

The shortest measures are the M-ACT (four items) and M-TOQ-5 (five items); the longest is the 45–item MTSM (Appendix 4). Apart from the M-ACT and M-TAQ, all assess migraine symptomology, including pain severity, and the wider impact on activities of daily living and/or work; the PPMQ-R also assesses limitations in social functions (Appendix ). The CORS, M-TOQ-15 and PPMQ-R assess the emotional burden of migraine; only the CORS and PPMQ-R also assess cognition and difficulty with thinking. Three measures assess if the patient has “returned to normal” – CORS, M-ACT, and M-TOQ. All assess confidence in/or satisfaction with treatment; the M-TOQ assesses treatment side-effects.

Only the PPMQ-R has acceptable evidence of measurement dimensionality and internal consistency reliability from studies of at least moderate methodological quality (Table 1; Appendix 7). For three measures – CORS, M-TOQ, and MTSM – evidence was acceptable but limited.

Only the M-ACT has acceptable evidence of temporal stability from several studies of fair methodological quality, supporting application in the assessment of groups (Table 1; Appendix 7).

Evidence for three measures – M-TAQ, M-TOQ, and PPMQ-R – was limited to single studies judged to be of fair quality (Table 1; Appendix 7) .

Only the PPMQ-R and MTSM have acceptable evidence of construct validity from good quality studies. For the remaining measures, evidence was limited (CORS, M-TAQ, and M-TOQ) or from poor quality (M-ACT) studies.

Following a two-month pharmaceutical trial, small to moderate change score correlations between the CORS and the PPMQ-R supported a priori hypothesised associations, providing acceptable, but limited, evidence of responsiveness. [38] Further criterion-based evidence, comparing the comparative CORS with change in CORS sub-sets at two months, provided additional, hypothesis-driven evidence of responsiveness. [38] Small to moderate effect size statistics were reported for the PPMQ-R in patients categorised by self-reported improvement (range 0.14 to 0.50) or worsening (range 0.06 to 0.23) in pain severity; the largest ES were reported for the Efficacy and Function domains. [43]

The Standard Error of Measurement (SEM) was calculated for the PPMQ-R, as a reflection of the within-individual minimal change in score (MIC). [43] Apart from the Cost domain (SEM 11.0), SEM estimates ranged 3.4 (Bothersome) to 5.4 (Total score), supporting an MIC recommendation of five points for the total score and Efficacy, Function and Ease of Use domains. Results suggest that the Cost domain is highly variable and not responsive to change in migraine severity or role limitation.

Estimates of the minimally important change and minimally important difference were reviewed for three headache-specific measures:MSQ v2.1 [36],

HIT-6 [31],

PPMQ-R. [43]Completion of the HIT-6 by Dutch patients with chronic tension-type headache [62] and episodic migraine [63] suggested a wider range of MIC values, from –2.5 [63] to –8.0 [62] than that determined in a US population with chronic daily headache (–3.7). [58]

The differences were largely explained by use of different anchors – where a greater perceived change was the imposed anchor, a larger MIC was calculated. An MIC of >8.0 suggests that improvement must be present in at least two of the six HIT-6 items [62], which may be judged a relevant treatment effect. [62, 63]

Similarly, suggested MID values range from –1.5 (episodic migraine) [63] to –2.3 (chronic daily headache). [58]

Generic PROMs (n = 6)

Evaluations of all generic measures in the headache population were very limited. There was no evidence exploring the content validity or relevance of the six reviewed generic measures with the headache population. There was no evidence of active patient collaboration.

Where applicable, there was no evidence of measurement dimensionality or internal consistency reliability (Table 1). Just one measure – the QWB-SA – had conflicting evidence of temporal stability from one study, judged to be of poor methodological quality [64] (Table 1; Appendix 7).

Acceptable evidence of construct validity from several studies judged to be of fair or good methodological quality was reviewed for both theSF-36 [36, 55, 65] and

the SF- 8 [7, 31, 57, 56] ;for the SF-12 evidence was limited (Table 1; Appendix 7).

For the remaining measures, evidence was limited (EQ-5D) or of poor quality (HUI-3, QWB).

There was no evidence of measurement responsiveness.

Discussion

High quality, relevant and acceptable PROMs provide patient-derived evidence of the impact of headache and the relative benefit of associated healthcare at both the time of the headache and the intervening period. The importance of capturing the patient perspective is reflected in the large number of measures included in this review. However, apart from two condition-specific – HIT-6 and MSQv2.1 – and one treatment-response – PPMQ-R – measures, for which strong evidence was reviewed, evidence was largely limited or not available.

This is the first systematic review to include a methodological assessment of both study and PROM quality in the headache population. Clarity in PROM focus is an essential, but often overlooked aspect of PROM development. [24, 80] Except for four condition-specific (MSQ v2.1, MSQoL, HIT and HIT-6) and four treatment-response measures (CORS, M-TOQ, MTSM and PPMQ-R), all lacked a clear description of the measurement aim.

Moreover, the condition-attribution of measures was not always self-evident: Just three ‘migraine-specific’ measures assessed the impact of “migraine” (FAIM, MSQ v2.1 and MSQoL). The HANA includes both “migraine” and “headache” in the item stem and, despite the name, the MIDAS assesses the impact of “headache”. It is suggested that the attribution of “headache” supports a “broader” assessment than would be achieved with “migraine”; moreover, many patients may be unaware of a migraine diagnosis. [3]

The HIT item content was informed by both migraine (MSQ and MIDAS) and headache-specific (HIMQ, HDI) measures; a content comparison failed to reveal any systematic differences in concept coverage, and further evaluation in a mixed population supported the uni-dimensionality of headache disability. [3] Evidence further supports the ability of the HIT to assess headache disability across a wide spectrum of impact, avoiding the potential for ceiling effects, following completion by headache and migraine populations. [3, 63] Just four measures (the HIT-6, HADLI, HDQ and MIDAS) have been evaluated in both headache and migraine populations. However, while evidence is strong for the HIT-6, the remaining measures should be applied with caution.

Except for two condition-specific (MSQv2.1 and MSQoL) and four treatment-response measures (CORS, M-TAQ, MTSM and PPMQ-R), the extent of patient participation was limited and poorly detailed. Moreover, except for three measures (MSQoL, PPMQ-R and EUROLIGHT) PROM relevance, content and face validity was not explicitly explored with patients and/or expert panels. Item content for the remaining measures was informed by a mix of qualitative research with clinicians, reference to existing measures, published literature and/or completed questionnaires. Successful treatment for headache disorders should seek to improve both overall quality of life, as well as an individual’s quality of life during the attack [37]; assessment should seek to capture these distinctions.

Although varying in length, there was a similarity of item content across condition-specific measures. Most assessed headache/migraine-related symptomology; pain severity was commonly assessed by headache-specific and treatment-response measures, but not by the migraine-specific measures. Just two measures (MSQv2.1 and HIT-6) assessed fatigue. Measures with a primary focus on symptomology have been criticised for failing to take into consideration the longer-term consequence of, or fear associated with, a potentially-severe headache or migraine, such as evading commitments or making plans. [81, 82] Nevertheless, except for the FAIM and HANA, all condition-specific and most treatment-response measures also assessed the wider impact of headache on social function and interactions, activities of daily living and/or work. Several measures (MSQv2.1, HIT, HIT-6, EUROLIGHT, CORS and PPMQ-R) also assessed both the emotional burden and cognitive impact of headache/migraine.

Three condition-specific (FAIM, MSQv2.1 and HIT-6) and one treatment-response (PPMQ-R) measures have strong evidence of both structural validity and reliability of internal consistency. Factor analysis supported the uni-dimensionality of the FAIM following completion by migraineurs, and the HIT-6 as a measure of “headache disability” following completion by mixed populations. The three-domain structure of the MSQv2.1 was supported – Role Restriction (RR), Role Prevention (RP) and Emotional Function (EF) – following completion in both chronic and episodic migraine populations. However, for most measures, evidence of structural validity or reliability of internal consistency was limited, from methodologically-poor quality studies, or not available. Evidence of temporal stability was also limited, and available only for the HIT, HIT-6, M-ACT, M-TAQ, M-TOQ and PPMQ-R. There was no evaluation of measurement error.

Five condition-specific (FAIM, MIDAS, MSQ v2.1, HIT and HIT-6),

two treatment-response (MTSM and PPMQ-R)

and two generic (SF-36 and SF-8) measures have acceptable evidence of construct validity from good quality studies.

For the remaining measures, evidence was limited, of poor methodological quality, or not available.

Methodological inadequacies included small sample sizes and a failure to hypothesise a priori the expected association between variables.

As reported in other reviews [18, 19], there was limited evidence of responsiveness: Just two studies [31, 38] provided acceptable, but limited, evidence for the CORS and HIT measures.

Evaluative measures require evidence of responsiveness to demonstrate that they can detect real change in condition over time; without such evidence, measures should be applied with caution.

While a limitation of the review is that we have only included evaluations in English, the context, setting and population are important in appraising evidence of PROM measurement and practical properties. [83]

Moreover, the diversity of reviewed measures reflects the wide range of assessment approaches in current use. Reviewed studies were of adults aged 18 years and over; with no upper age-limit imposed. All reviewed studies excluded people with significant co-morbidities.

We are confident that the results are generalisable to the wider population of English-speaking adults with headache, but may not reflect the experience of adults with headache who have significant co-morbidities or do not speak English.

All data from included studies was double extracted and agreement checked (KH, TM). However, the COSMIN grading and synthesis score was applied by a single, experienced reviewer (KH). Although applied in several recent reviews [19, 84], the grading system itself lacks robust evidence of reliability and validity and should therefore be interpreted with caution.

The lack of reporting guidance and significant heterogeneity in outcome assessment detailed in this review highlight the importance of establishing guidance on outcome reporting in this population. Future research should seek to establish international, multi-perspective guidance for a core set of outcomes to include in future headache research and across routine practice settings. The first step in this process is to seek consensus on which outcomes should be assessed, as a minimum, in future clinical trials or routine practice setting. [85] Informed by recommendations from this review, the second step is to determine the “best way” to assess these core outcomes.

Although many PROMs were reviewed following their evaluation in the headache and/or migraine population, study methodological quality was often poor and evidence of essential measurement properties largely unavailable or limited. Such limitations hinder PROM data interpretation from clinical trials, audit, or quality assurance initiatives. However, three measures – Headache Impact Test 6-item (HIT-6), Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (MSQ v2.1) Patient Perception of Migraine Questionnaire (PPMQ-R) – had acceptable, and often strong, evidence of reliability and validity following completion by patients with headache (HIT-6) or migraine (HIT-6, MSQv2.1, PPMQ-R), and are recommended for consideration in future clinical research and routine practice settings as measures of headache-specific impact, migraine-specific impact, or migraine-treatment response respectively. However, the similarity of item content across all three measures suggests that a further exploration of the attribution, relevance and acceptability of the measures with representative members of the patient population is warranted. Further comparative evidence of widely-used generic measures and evidence of measurement responsiveness of all measures is urgently required.

Article highlights:

Despite the large number of reviewed PROMs currently used with patients with headache, most have not involved patients in the development process and may lack relevance to the patients’ experience of headache. Most also lack clarity with regard to measurement aim and have limited evidence of essential measurement properties, limiting confidence in data interpretation. These PROMs should be used and interpreted with caution.

Strong evidence of reliability and validity was reviewed for three measures, HIT-6, MSQv2.1 and the PPMQ-R, supporting recommendation for consideration in future clinical research or routine practice settings. However, unlike the MSQv2.1 and PPMQ-R, patients were not involved in item generation for the HIT-6.

The review has highlighted significant heterogeneity in outcome reporting in headache studies, raising concerns over reporting bias and limiting the conduct of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of evidence. International multi-perspective consensus on the most important outcomes – both which outcomes and how to assess them – is required, and can be supported by the findings from this review.

Supplementary Material

All the Appendices and their associated Tables. (1.5M, pdf, 64 pages)

Acknowledgements

The CHESS team: Professor Martin Underwood (Chief investigator), Felix Achana, David Boss, Ms Mary Bright, Fiona Caldwell, Dr Dawn Carnes, Dr Brendan Davies, Professor Sandra Eldridge, Dr David Ellard, Simon Evans, Professor Frances Griffiths, Dr Kirstie Haywood, Dr Siew Wan Hee, Dr Manjit Matharu, Hema Mistry, Professor Stavros Petrou, Professor Tamar Pincus, Dr Katrin Probyn, Dr Harbinder Sandhu, Professor Stephanie Taylor, Arlene Wilkie, Helen Higgins, Dr Vivien Nichols, Dr Shilpa Patel, Dr Rachel Potter, Kimberley White.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research programme (RP-PG-1212-20018). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

References:

Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, et al.

Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States:

Data from the American Migraine Study II.

Headache 2001; 41: 646–657Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al.

Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy.

Neurology. 2007;68:343-349.Bjorner JB, Kosinski M, Ware JE., Jr

Calibration of an item pool for assessing the burden of headaches:

An application of item response theory to the Headache Impact Test (HITTM).

Qual Life Res 2003; 12: 913–933Castillo J, Munoz P, Guitera V, et al.

Epidemiology of chronic daily headache in the general population.

Headache 1999; 39: 190–196Wang S, Fuh J, Lu S, et al.

Chronic daily headache in Chinese elderly:

Prevalence, risk factors, and biannual follow-up.

Neurology 2000; 54: 314–331Leonardi M, Steiner TJ, Scher AT, et al.

The global burden of migraine: Measuring disability in headache disorders with

WHO’s Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF).

J Headache Pain 2005; 6: 429–440Turner-Bowker DM, Bayliss MS, Ware JE, Jr, et al.

Usefulness of the SF-8TM Health Survey for comparing the

impact of migraine and other conditions.

Qual Life Res 2003; 12: 1003–1012Silberstein S, Tfelt-Hansen P, Dodick DW, et al.

Guidelines for controlled trials of prophylactic treatment

of chronic migraine in adults.

Cephalalgia 2008; 28: 484–495Tfelt-Hansen P, Pascual J, Ramadan N, et al.

Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine:

Third edition. A guide for investigators.

Cephalalgia 2012; 32: 6–38Streiner DL, Norman GR, Cairney J.

Health Measurement Scales: A practical guide to their development

and use (5th edition),

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.de Vet H, Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, et al.

Measurement in medicine. A practical guide,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.Rendas-Baum RL, Bloudek M, Maglinte GA, et al.

The psychometric properties of the Migraine-Specific Quality of Life

Questionnaire version 2.1 (MSQ) in chronic migraine patients.

Qual Life Res 2013; 22: 1123–1133Terwee CB, Jansma EP, Riphagen II, de Vet HC.

Development of a methodological PubMed search filter for finding studies on

measurement properties of measurement instruments.

Qual Life Res. 2009 Oct;18(8), 1115-1123.Terwee CB, Prinsen CA, Ricci Garotti MG, et al.

The quality of systematic reviews of health-related outcome measurement instruments.

Qual Life Res 2016; 25: 767–779Andrasik F, Lipchik GL, McCrory D, et al.

Outcome measurement in behavioural headache research:

Headache parameters and psychosocial outcomes.

Headache 2005; 45: 429–437McCrory DC, Gray RN, Tfelt-Hansen P, et al.

Methodological issues in systematic reviews of headache trials:

Adapting historical diagnostic classifications and

outcome measures to present-day standards.

Headache 2005; 45: 459–465Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al.

Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties

of health status questionnaires.

J Clin Epidemiol 2007; 60: 34–42Haywood KL, Staniszewska S, Chapman S.

Quality and acceptability of patient-reported outcome measures used

in chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME):

A systematic review.

Qual Life Res 2012; 21: 35–52Conijn AP, Jens S, Terwee CB, et al.

Assessing the quality of available patient reported outcome measures for intermittent claudication:

A systematic review using the COSMIN checklist.

Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2015; 49: 316–334Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al.

The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology,

and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes.

J Clin Epidemiol 2010; 63: 737–745Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL, et al.

Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies

on measurement properties: A scoring system for the COSMIN checklist.

Qual Life Res 2012; 21: 651–657Staniszewska S, Haywood KL, Brett J, et al.

Patient and public involvement in patient-reported

outcome measures: Evolution not revolution.

Patient 2012; 5: 79–87Haywood K, Lyddiatt A, Brace-McDonnell SJ, et al.

Establishing the values for patient engagement (PE) in

health-related quality of life (HRQoL) research:

An international, multiple-stakeholder perspective.

Qual Life Res 2016; 26: 1393–1404U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Guidance for Industry Patient-Reported Outcome Measures:

Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims

Food and Drug Administration (Dec 2009)Ferrans CE, Zerwic JJ, Wilbur JE, et al.

Conceptual model of health-related quality of life.

J Nurs Schol 2005; 37: 336–342Bakas T, McLennon SM, Carpenter JS, et al.

Systematic review of health-related quality of life models.

Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012; 10: 134–134Elbers RG, Rietberg MB, van Wegen EE, et al.

Self-report fatigue questionnaires in multiple sclerosis,

Parkinson’s disease and stroke: A systematic review

of measurement properties.

Qual Life Res 2012; 21: 925–944Andrée C, Vaillant M, Barre J, et al.

Development and validation of the EUROLIGHT questionnaire to

evaluate the burden of primary headache disorders in Europe.

Cephalalgia 2010; 30: 1082–1100Vernon H, Lawson G.

Development of the headache activities of daily living index:

Initial validity study.

J Manip Physiol Ther 2015; 38: 102–111Niere K, Quin A.

Development of a headache-specific disability questionnaire

for patients attending physiotherapy.

Man Ther 2009; 14: 45–51Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, Bjorner JB, et al.

A Six-item Short-form Survey for

Measuring Headache Impact:

The HIT-6

Quality of Life Research 2003 (Dec); 12 (8): 963–794Magnusson JE, Riess CM, Becker WJ.

Modification of the SF-36 for a headache population

changes patient-reported health status.

Headache 2012; 52: 993–1004Pathak DS, Chisolm DJ, Weis KA.

Functional Assessment in Migraine (FAIM) questionnaire: development

of an instrument based upon the WHO’s International Classification

of Functioning, Disability, and Health.

Value Health 2005; 8: 591–600Cramer JA, Silberstein SD, Winner P.

Development and validation of the headache needs assessment (HANA) survey.

Headache 2001; 41: 402–409Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Whyte J, et al.

An international study to assess reliability of the

Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) score.

Neurology 1999; 53: 988–994Martin BC, Pathak DS, Sharfman MI, et al.

Validity and reliability of the migraine-specific

quality of life questionnaire (MSQ Version 2.1).

Headache 2000; 40: 204–215McKenna SP, Doward LC, Davey KM.

The development and psychometric properties of the MSQOL:

A migraine-specific quality-of-life instrument.

Clin Drug Investig 1998; 15: 413–423Coon CD, Fehnel SE, Davis KH, et al.

The development of a survey to measure completeness

of response to migraine therapy.

Headache 2012; 52: 550–572Dowson AJ, Tepper SJ, Baos V, et al.

Identifying patients who require a change in their current acute migraine treatment:

The Migraine Assessment of Current Therapy (Migraine-ACT) questionnaire.

Curr Med Res Opin 2004; 20: 1125–1135Chatterton ML, Shechter A, Curtice WS, et al.

Reliability and validity of the migraine therapy

assessment questionnaire.

Headache 2002; 42: 1006–1015Lipton RB, Kolodner K, Bigal ME, et al.

Validity and reliability of the migraine-treatment

optimization questionnaire.

Cephalalgia 2009; 29: 751–759Patrick DL, Martin ML, Bushnell DM, et al.

Measuring satisfaction with migraine treatment:

Expectations, importance, outcomes, and global ratings.

Clin Ther 2003; 25: 2920–2935Revicki DA, Kimel M, Beusterien K, et al.

Validation of the revised patient perception of migraine questionnaire:

Measuring satisfaction with acute migraine treatment.

Headache 2006; 46: 240–252Ware JE, Sherbourne CD.

The MOS 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36). I.

Conceptual framework and item selection.

Med Care 1992; 30: 473–483Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD.

A 12-item short-form health survey: Construction of scales

and preliminary tests of reliability and validity.

Med Care 1996; 34: 220–233Ware J, Kosinski M, Dewey J, et al.

How to score and interpret single-item health status measures:

A manual for users of the SF-8 Health Survey,

Boston: Quality Metric, 2001.The EuroQol Group.

EuroQol – a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life.

Health Policy 1990; 16: 199–208Feeny D, Furlong W, Torrance GW, et al.

Multi-attribute and single-attribute utility functions

for the health utilities index mark 3 system.

Med Care 2002; 40: 113–128Kaplan RM.

Quality of life assessment for cost/utility

studies in cancer.

Cancer Treat Rev 1993; 19: 85–96Andresen EM, Rothenberg BM, Kaplan RM.

Performance of a self-administered mailed version of the

Quality of Well-Being (QWB-SA) questionnaire among older adults.

Med Care 1998; 36: 1349–1360Cole JC, Lin P, Rupnow MFT.

Validation of the Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire version 2.1

(MSQ v. 2.1) for patients undergoing prophylactic migraine treatment.

Qual Life Res 2007; 16: 1231–1237Patrick DL, Hurst BC, Hughes J.

Further development and testing of the migraine-specific

quality of life (MSQOL) measure.

Headache 2000; 40: 550–560Rendas-Baum R, Yang M, Varon SF, et al.

Validation of the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6)

in patients with chronic migraine.

Health Qual Life Outcomes 2014; 12: 117–117Bagley CL, Rendas-Baum R, Maglinte GA, et al.

Validating migraine-specific quality of life questionnaire

v2.1 in episodic and chronic migraine.

Headache 2012; 52: 409–421Kawata AK, Coeytaux RR, DeVellis RF, et al.

Psychometric properties of the HIT-6 among patients

in a headache-specialty practice.

Headache 2005; 45: 638–643Yang M, Rendas-Baum R, Varon SF, et al.

Validation of the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6TM)

across episodic and chronic migraine.

Cephalalgia 2011; 31: 357–367Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Bjorner JB, et al.

Applications of computerized adaptive testing (CAT)

to the assessment of headache impact.

Qual Life Res 2003; 12: 935–952Coeytaux RR, Kaufman JS, Chao R, et al.

Four methods of estimating the minimal important difference score

were compared to establish a clinically significant change

in Headache Impact Test.

J Clin Epidemiol 2006; 59: 374–380Lipton RB, Rosen NL, Ailani J, et al.

Pooled results from the PREEMPT randomized clinical trial program.

Cephalalgia 2016; 36: 899–908Cole J, Lin P, Rupnow M.

Minimal important differences in the Migraine-Specific

Quality of Life Questionnaire (MSQ) version 2.1.

Cephalalgia 2009; 29: 1180–1187Dodick DW, Silberstein S, Saper J, et al.

The impact of topiramate on health-related quality

of life indicators in chronic migraine.

Headache 2007; 47: 1398–1408Castien RF, Blankenstein AH, Windt DA, et al.

Minimal clinically important change on the Headache Impact Test-6

questionnaire in patients with chronic tension-type headache.

Cephalalgia 2012; 32: 710–714Smelt AF, Assendelft WJ, Terwee CB, et al.

What is a clinically relevant change on the HIT-6 questionnaire?

An estimation in a primary-care population of migraine patients.

Cephalalgia 2014; 34: 29–36Sieber WJ, David KM, Adams JE, et al.

Assessing the impact of migraine on health-related quality of life:

An additional use of the quality of well-being scale-self-administered.

Headache 2000; 40: 662–671Martin ML, Patrick DL, Bushnell DM, et al.

Further validation of an individualized migraine

treatment satisfaction measure.

Value Health 2008; 11: 904–912Stewart WF, Lipton R, Kolodner K, et al.

Reliability of the migraine disability assessment score

in a population- based sample of headache sufferers.

Cephalalgia 1999; 19: 107–114Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Kolodner KB, et al.

Validity of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) score

in comparison to a diary-based measure in a population

sample of migraine sufferers.

Pain 2000; 88: 41–52Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Kolodner K.

Migraine disability assessment (MIDAS) score:

Relation to headache frequency, pain intensity,

and headache symptoms.

Headache 2003; 43: 258–265Bigal ME, Rapoport AM, Lipton RB, et al.

Assessment of migraine disability using the migraine disability assessment

(MIDAS) questionnaire: A comparison of chronic migraine with episodic migraine.

Headache 2003; 43: 336–342Sauro KM, Rose MS, Becker WJ, et al.

HIT-6 and MIDAS as measures of headache disability

in a headache referral population.

Headache 2010; 50: 383–395Blumenfeld AM, Varon SF, Wilcox TK, et al.

Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic migraineurs:

Results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS).

Cephalalgia 2011; 31: 301–315Stafford MR, Hareendran A, Ng-Mak DS, et al.

EQ-5D-derived utility values for different levels of

migraine severity from a UK sample of migraineurs.

Health Qual Life Outcomes. Epub ahead of print 12 June 2012.

DOI: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-65Gillard PJ, Devine B, Varon SF, et al.

Mapping from disease-specific measures to health-state

utility values in individuals with migraine.

Value Health 2012; 15: 485–494Kilminster SG, Dowson AJ, Tepper SJ, et al.

Reliability, validity, and clinical utility of the

migraine-ACT questionnaire.

Headache 2006; 46: 553–562Kimel M, Hsieh R, McCormack SP, et al.

Validation of the revised Patient Perception of Migraine Questionnaire

(PPMQ-R): Measuring satisfaction with acute migraine treatment in clinical trials.

Cephalalgia 2008; 28: 510–523Davis KH, Black L, Sleath B.

Validation of the Patient Perception of Migraine Questionnaire.

Value Health 2002; 5: 422–430Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Stewart WF.

Assessing disability using the migraine disability assessment questionnaire.

Expert Rev Neurother 2003; 3: 317–325Xu R, Insinga RP, Golden W, et al.

EuroQol (EQ-5D) health utility scores for patients with migraine.

Qual Life Res 2011; 20: 601–608Brown JS, Neumann PJ, Papadopoulos G, et al.

Migraine frequency and health utilities: Findings from a multisite survey.

Value Health 2008; 11: 315–321Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al.

Content validity-establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed

patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation:

ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: part 1–

eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument.

Value Health 2011; 14: 967–977Blau JN.

Fears aroused in patients by migraine.

Br Med J (Clin Res) 1984; 288: 1126–1126Wagner TH, Patrick DL, Galer BS, et al.

A new instrument to assess the long-term quality of life effects from migraine:

Development and psychometric testing of the MSQOL.

Headache 1996; 36: 484–492Yost KJ, Cella D, Chawla A, et al.

Minimally important differences were estimated for the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal (FACT-C) instrument

using a combination of distribution- and anchor-based approaches.

J Clin Epidemiol 2005; 58: 1241–1251Haywood KL, Brett J, Tutton E, et al.

Patient-reported outcome measures in older people with hip fracture:

A systematic review of quality and acceptability.

Qual Life Res 2017; 26: 799–812Williamson PR, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, et al.

Developing core outcome sets for clinical trials:

Issues to consider.

Trials 2012; 13: 132–132.

Return to HEADACHE

Since 2-10-2023

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |