Outcomes of Spinal Manipulation and Neurological

Rehabilitation for a Patient With Chronic

Tension-Type Headaches and a

Prior History of Head TraumaThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Cureus 2025 (Sep 8); 17 (9): e91838 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Daniel J Perman • Shelbi Hughes • Paula Murillo • Krista Ward

Nexus Brain Center,

Life Chiropractic College West,

Hayward, USA.

FROM: CAM OsteopathyChronic tension-type headaches (TTH) can be a debilitating condition that may include peripheral vestibular system involvement. This case report describes the response to spinal manipulation (SM) and neurologic rehabilitation for a 44-year-old male with TTH complicated by a history of concussion. The patient presented to a chiropractic teaching clinic with over 15 years of daily headaches, lasting about seven hours, and rated 5/10 on a visual analog scale. The patient recalled no single causal event. Several years prior to headache onset, the patient had multiple concussions from football and military/police force occupation. Baseline findings included nystagmus, unsteady gaze holding, and latency and fatigue with saccades in all directions. Over the course of seven months, the patient received 24 visits of SM and 17 treatments of trans-auricular vagus nerve stimulation, repetitive peripheral somatosensory stimulation, photobiomodulation, and gaze stabilization exercises. The patient reported 50% headache improvement after seven weeks and 90% improvement at 20 weeks, at which point headache frequency was once a week for one hour or less. No nystagmus was observed in the 27-week exam. Chronic TTH improved with SM and neurologic rehabilitation. While past clinical trials document similar TTH improvement with SM, little is known about neurological rehabilitation treatments for TTH. This case study suggests that research in this area may be warranted.

Keywords: brain concussion; chronic tension-type headache (ctth); neurological rehabilitation; single-case study; spinal manipulation.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Tension-type headaches (TTH) affect 30-78% of the population, and chronic TTH is considered to be a debilitating disease that greatly affects quality of life (QoL) and contributes to significant disability and costs. [1, 2] Diagnostic criteria state that chronic TTH headaches (CTTH) must occur at least 15 days per month and at least 180 days or more per year. [1] The headaches must also last hours to days and have at least two of the following criteria: bilateral location, pressing or tightening quality, mild-to-moderate intensity, and not affected negatively by physical activity. [1] Patients with TTH may also present with peripheral vestibular system involvement. In one study, 3% of TTH patients exhibited spontaneous nystagmus, and 12% presented with bilateral vestibulopathy. [3]

Previous research suggests spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) can help relieve TTH. [4-6] In one study of eight sessions of upper cervical SMT and patient exercise, TTH frequency was reduced by 3.3 days and headache pain by 3.8 on the visual analog scale (VAS). [4] The decreased frequency and pain intensity persisted three months post intervention and were greater than the decreases observed for participants receiving exercise only or exercise and myofascial release. [4] Little is known about the clinical effectiveness of neurorehabilitation therapies to address TTH.

This case report describes the response to neurological rehabilitation therapies and SMT for a patient with CTTH complicated by a history of multiple concussions and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This retrospective case report received a determination of not human subjects research. The patient consented to publication. The authors used the Consensus-based Standards for the Reporting of Articles in Healthcare (CARE) checklist as a writing framework.

Case Presentation

Patient history and exam

A 44-year-old male patient presented to a chiropractic school’s health center (HC) with chronic moderate intermittent cephalgia, which began in his mid-late 20s. He described the pain as sharp/stabbing in the temporal region and throbbing/pounding in the occipital region. VAS pain was reported as 5/10. The headaches occurred daily, beginning in the mornings and lasting about seven hours. He reported the pain was exacerbated by wearing a helmet for work and looking down for long periods of time, but was not aggravated by physical activity. The headache pain was relieved or reduced by massage and over-the-counter medication. The patient recalled no event that caused the headaches; they came on slowly in frequency and severity until they became continuous and unbearable. The patient did not report any prodrome symptoms, although sometimes he saw kaleidoscope patterns in his visual field when temporal headaches were bad. Additional complaints included shoulder pain, low back pain, dizziness, bilateral tinnitus, and poor short-term memory.

The patient denied a family history of chronic disease. Medications included bupropion for anxiety and depression, which the patient began two weeks prior to initiating SMT; amlodipine for hypertension; naproxen for inflammation; and Symbicort for asthma. Past history included five mild traumatic brain injuries (mTBIs) due to blunt sport and occupational traumas during the patient’s early 20s. The only medical treatments the patient received for these were jaw and dental work. The patient may have also experienced mTBIs due to military blast trauma. Two years prior to initiating care, the patient was diagnosed at the United States Department of Veterans Affairs for PTSD and temporomandibular joint dysfunction.

Table 1

page 3

Figure 1 The patient reported contentment with his police officer job, 50-60 hours per week. He reported enjoying exercising three to five days/week for one to two hours. Alcohol use was reported as one to three beverages per week, and caffeine was reported as three cups per day. The patient denied tobacco use. The patient described getting about five hours of interrupted sleep/night. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was measured with the RAND-36 instrument, which is equivalent to the commonly used SF-36 survey. [7] RAND-36 scores are displayed in Table 1.

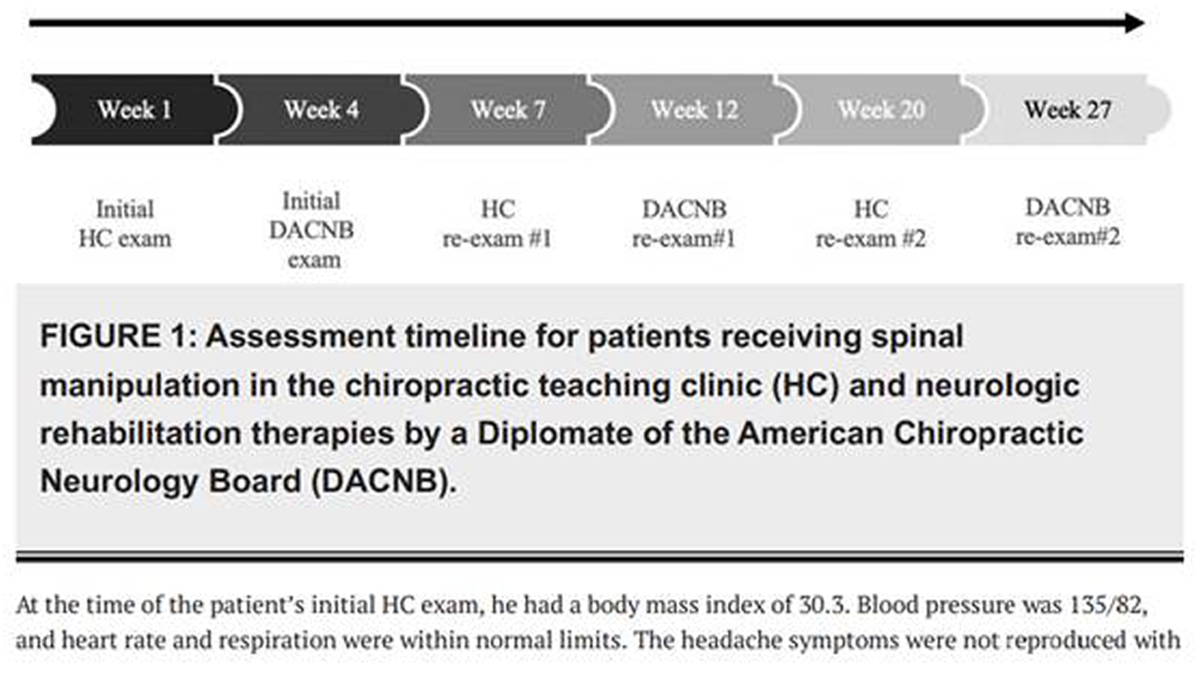

The patient was initially examined in the HC, and then he was referred to on-site neurology assessment and rehabilitation care by a Diplomate of the American Chiropractic Neurology Board (DACNB). In the course of seven months, the patient was re-examined twice in the HC (weeks 7 and 20) and twice by the DACNB (weeks 12 and 27; Figure 1).

At the time of the patient’s initial HC exam, he had a body mass index of 30.3. Blood pressure was 135/82, and heart rate and respiration were within normal limits. The headache symptoms were not reproduced with the cervical orthopedic exam. Neurologic findings were normal, except for decreased vibration sensation along the right T1 dermatome. During the cranial nerve exam, the patient was asked to fixate on a point on a distant wall. He was then asked to direct his vision to a business card held about 12 inches from his face. The patient reported blurry words for 10-15 seconds before his eyes were able to accommodate. See Table 1 for additional exam findings.

Cervical X-rays were ordered due to trauma history and spinal tenderness with palpation. X-ray findings included right convex lower cervical scoliosis; flattening of the cervical lordosis; uncovertebral hypertrophy C5-C6 on the left; and facet arthrosis C4-C7 on the left.

Figure 2

Table 2

page 4Initial DACNB exam included video-oculography (VOG) assessments of spontaneous nystagmus, gaze holding, pursuits, saccades, and optokinetic nystagmus using a Micromedical Visual Eyes 525 device (Interacoustics, Middelfart, Denmark). All targets were positioned 36 inches from the patient on a 50-inch LCD TCK 59S455 television (Figure 2). A dot on the screen was centered relative to the patient's eyeline. The patient was instructed to hold their head still and open their eyes wide while staring at a series of targets.

The DACNB exam also included an assessment of proprioceptive, vestibulospinal, and oculospinal function using the Comprehensive Assessment of Postural Systems (CAPS®) (Vestibular Technologies LLC, Cheyenne, WY). The CAPS assessment included two protocols for assessing balance, including the Modified Clinical Test for Sensory Interaction on Balance (mCTSIB), a commonly used test with the addition of head movements as described by Cohen et al. [8] See Table 2 for initial VOG, CAPS, and other bedside neurologic exam findings.

Diagnosis

The patient’s history and presentation met all of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) criteria for intractable CTTH. [1] A lack of temporal relationship between the initiation of the headaches and either a cervical disorder or prior concussion differentiated the diagnosis from cervicogenic headaches and persistent headaches attributed to traumatic injury. The patient had no nausea, vomiting, photophobia, or phonophobia, which excluded migraine headaches. There were no financial or cultural diagnostic challenges. The patient was also diagnosed with unspecified subjective visual disturbances.

Treatment

The patient received SMT approximately two times a week in the HC for the first seven weeks of care (Figure 1). Between weeks seven and 19, the frequency of SMT decreased to once per week, and then after 20 weeks, to two times per month. Between week four and week 27 of care, the patient was also seen 17 times by the DACNB.

Treatment by the DACNB was delayed until week four due to scheduling and referral lag. DACNB visits included the following: trans-auricular vagus nerve stimulation using high volt galvanic stimulator CS6102 (Medical Systems, Minneapolis, MN) (15 minutes, alternating sides between sessions); repetitive peripheral somatosensory stimulation of the right trigeminal nerve (three sets of 15 seconds at three locations with the Cadwell Sierra Wave instrument (Cadwell Industries, Kennewick, WA); cold laser therapy; and transcranial photobiomodulation (six minutes) with the FX405 laser (Erchonia, Fountain Inn, SC). Using Dynavision D2TM (Dynavision, Brecon, OH), the patient also received training (10-15 minutes/visit) in spatial awareness, reaction time, and cognitive and hand-eye coordination with progressively more challenging exercises each visit.

The patient was also instructed in convergence and horizontal and vertical gaze stability exercises to be performed three times/day. Convergence exercises involved moving a popsicle stick with a target at the tip from arm's distance towards the nose while trying to keep the target in focus. Gaze stability exercises were adapted from Carrick et al.’s work. [9] The patient was compliant with exercises (two times/day) and tolerated treatments well. No adverse events were observed.

Outcomes

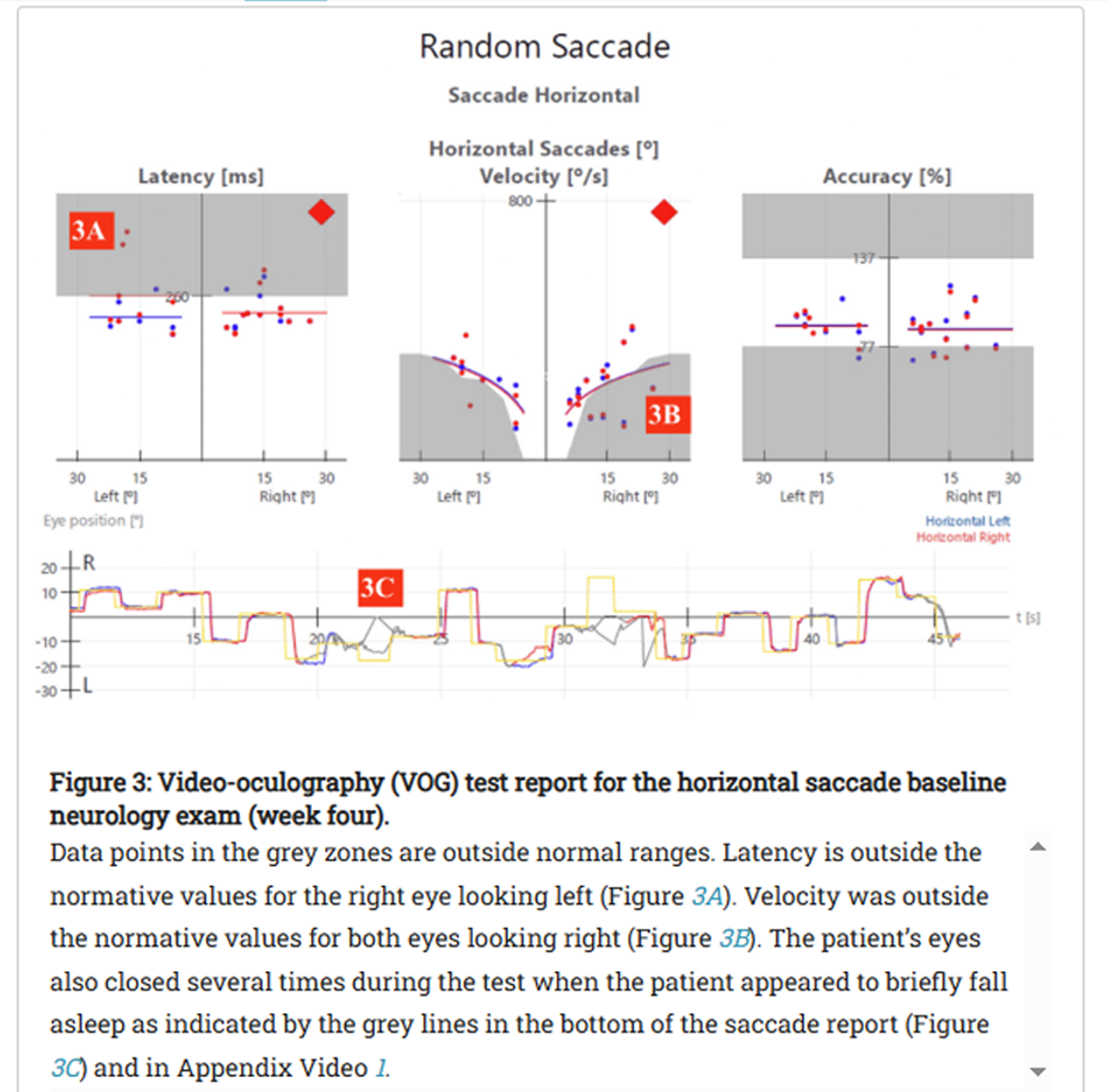

Figure 3

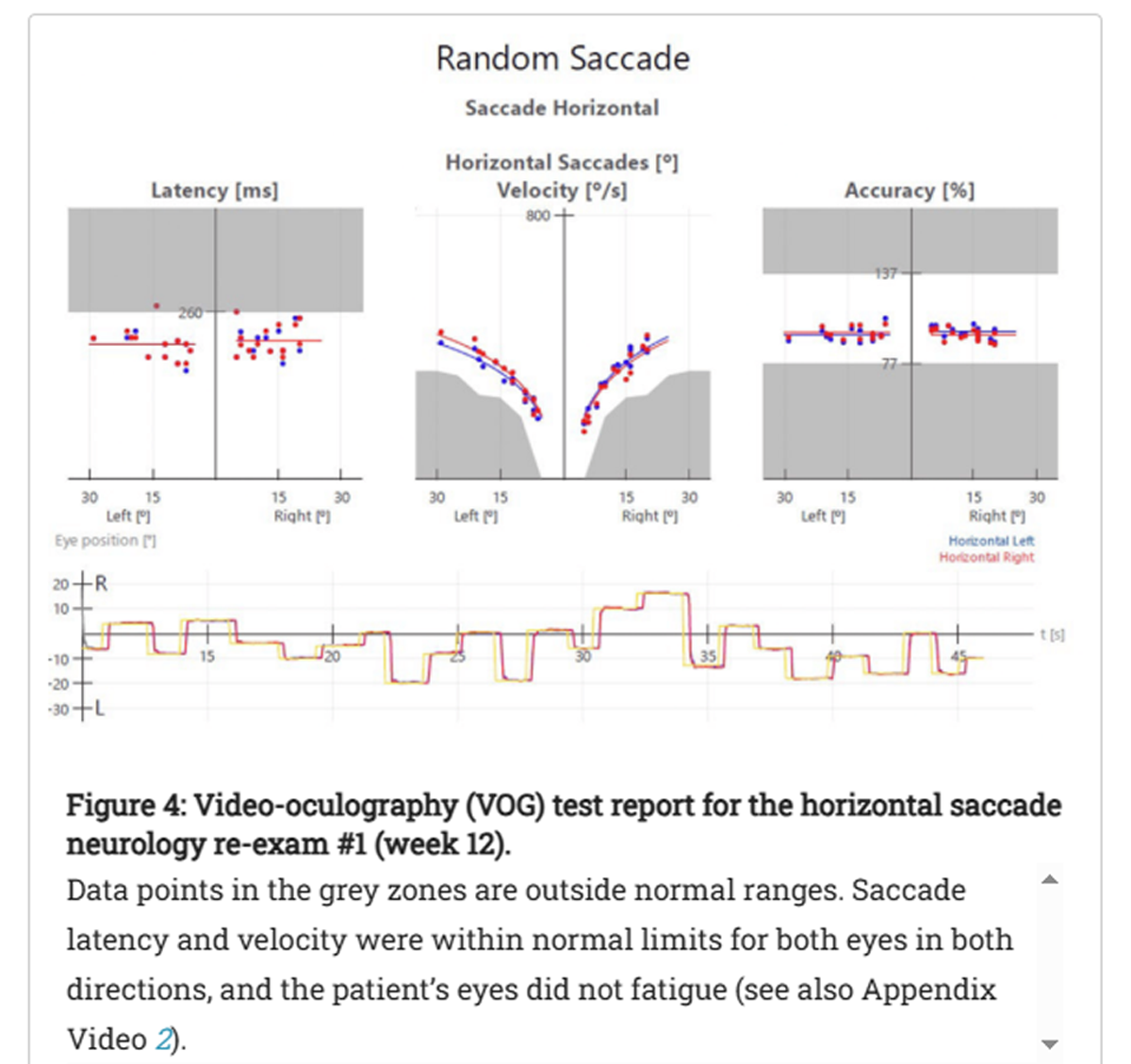

Figure 4 The patient initially presented to the clinic with headaches occurring every day for about seven hours a day, with a 5/10 VAS for pain. After five months of care, the patient reported 90% headache improvement with frequency decreasing from seven days/week to about once a week and duration decreasing from seven hours/headache day to one to two hours/headache day. Between the initial and 20-week exams, the patient reported a 67% increase in the number of past 30 days feeling healthy and full of energy, and a 50% decrease in the past 30 days when physical health was not good. QoL improved for five of the nine RAND-36 subscales (Table 1). While the patient did not report an increase in hours of sleep per night, he did describe less difficulty falling asleep following care.

Clinician-reported outcomes also improved. Functional oscillopsia was not seen after the initial exam, and mild to no nystagmus was seen in the first and second DACNB re-exams, respectively (Table 2). In addition, saccade latency was reduced, and velocity was improved from the initial exam to the first DACNB re-exam (Figures 3-4 and Appendix Videos 1-2).

Discussion

The prevalence of TTH and PTSD in the veteran population is estimated to be 12% and 40%, respectively, and veterans with PTSD have four times the odds of migraine or TTH. [10] Although the term “tension type” may connotate that the headache is due to stress and muscular tension, previous authors have suggested these headaches have multiple concurrent mechanisms of pathophysiological origin with more of a neurological basis than any psychological origin. [11, 12] The etiology of CTTH includes increased sensitization at the neurological level due to continued and chronic pain signals coming from the myofascial tissues surrounding the head. [13] This case exemplifies a multifactorial etiology, given the patient’s history of PTSD and multiple head injuries.

Prior research suggests that the patient’s presentation of headaches and neuro-ocular findings is not unique, especially given his history of mTBIs. Patients with mTBIs have presented with accommodative dysfunction and saccadic latency and fatigue, even several years post concussion. [14] Blast exposures can injure the frontal and prefrontal cortices and cerebellum associated with ocular motor control. [14]

This case study describes the improvement of CTTH, QoL, and neurologic findings during seven months of SMT and neurologic rehabilitation therapies. Strengths of this study are the use of validated patient and clinician-reported outcome measures. The patient experienced reduced headache frequency and function; improved balance with Romberg’s test; a reduction in nystagmus and latency/fatigue with saccades with VOG assessments; and reduced limitations due to physical health as reported on the RAND-36. These results are similar to previously reported reductions in TTH frequency and photophobia with suboccipital soft tissue inhibition and occiput-atlas-axis manipulation. [6] Neuromodulation is a recommended therapy for migraines [15], and this case supports investigating its use in CTTH.

Due to the inherent limitations of case reports, the results of this study can not be generalized nor used as evidence for the efficacy of the treatments described. In addition, this retrospective observation prevents identification of the specific origins of the patient’s symptoms, and the exact causes of his symptomatic relief remain unknown. Specifically, we do not know if the patient’s presentation of headaches and neuro-ocular findings were related to prior mTBIs or if the improvements in balance and eye tracking were due to SMT, neurologic rehabilitation, and/or another contributing factor.

The patient may have experienced changes in his health due to the bupropion he started taking two weeks prior to initiating SMT. While the authors of this case study found no studies on bupropion or other atypical antidepressants as a therapy for headaches, there is evidence for other antidepressants having a therapeutic effect on CTTH. [16] The patient also received myofascial release for right shoulder pain during the treatment phase, which may have also impacted his QoL.

Future randomized controlled clinical studies are needed to assess the efficacy of neurologic rehabilitation for CTTHs. To better document the clinical significance and to calculate the reliable change index for future related case studies, further research is needed to establish the minimal clinically important difference and standard errors of measurement for the RAND-36 in headache populations, similar to the Swedish study published by Grönkvist et al. in 2024. [17]

Conclusions

This case study describes the response to SMT and neurological rehabilitation for CTTH in a 44-year-old male patient. The patient's QoL and headache frequency and intensity improved, and clinical outcomes included reduced oscillopsia, nystagmus, and saccade latency. The results can not be generalized from this single patient. Future research is needed to identify the clinical significance of these outcomes and to test the efficacy of the treatments in a large sample with a randomized controlled clinical trial design.

Meanwhile, the results of this study and the cited literature in the report support thorough neuro-ocular assessments in patients with CTTH, especially those with a history of concussion. SMT may provide benefits for post concussive patients with CTTH, a finding supported by previous research on SMT and TTH. Furthermore, this case study indicates that neuro-rehabilitation therapies may prove beneficial in patients exhibiting visual disturbances with TTH.

Supplementary Material

Video 1: Initial neurology exam random saccade - horizontal.

Video 2: First neurology re-exam random saccade - horizontal.

References:

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS):

The International Classification of Headache Disorders,

3rd edition (beta version).

Cephalalgia. 2013, 33:629-808.

10.1177/0333102413485658Ahmed F, Parthasarathy R, Khalil M:

Chronic daily headaches.

Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2012, 15:S40-50.

10.4103/0972-2327.100002Zhang AJ, Yu LQ, Zhou L, Cong XZ, Liu QH, Li W, Zhang AY:

Presence of spontaneous nystagmus, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo,

and Tumarkin fall in patients with primary headache and

their responses to caloric and video head impulse tests.

J Clin Med Res. 2024, 16:63-74.

10.14740/jocmr5088Corum M, Aydin T, Medin Ceylan C, Kesiktas FN:

The comparative effects of spinal manipulation, myofascial release

and exercise in tension-type headache patients with neck pain:

a randomized controlled trial.

Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2021, 43:101319.

10.1016/j.ctcp.2021.101319Rolle G, Tremolizzo L, Somalvico F, Ferrarese C, Bressan LC:

Pilot trial of osteopathic manipulative therapy for

patients with frequent episodic tension-type headache.

J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2014, 114:678-85.

10.7556/jaoa.2014.136Espí-López GV, Rodríguez-Blanco C, Oliva-Pascual-Vaca A, Benítez-Martínez JC:

Effect of Manual Therapy Techniques on Headache Disability

in Patients With Tension-type Headache.

Randomized Controlled Trial

Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2014 (Dec); 50 (6): 641–647Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Mazel RM:

The RAND 36-Item Health Survey 1.0 (SF 36)

Health Econ. 1993, 2:217-27.

10.1002/hec.4730020305Cohen HS, Mulavara AP, Stitz J, Sangi-Haghpeykar H, Williams SP, Peters BT:

Screening for vestibular disorders using the modified clinical test

of sensory interaction and balance and tandem walking with eyes closed.

Otol Neurotol. 2019, 40:658-65.

10.1097/MAO.0000000000002173Carrick FR, Clark JF, Pagnacco G, Antonucci MM, Hankir A, Zaman R, Oggero E:

Head-eye vestibular motion therapy affects the mental and

physical health of severe chronic postconcussion patients.

Front Neurol. 2017, 8:414.

10.3389/fneur.2017.00414Afari N, Harder LH, Madra NJ, Heppner PS, Moeller-Bertram T, King C, Baker DG:

PTSD, combat injury, and headache in veterans

returning from Iraq/Afghanistan.

Headache. 2009, 49:1267-76.

10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01517.xJensen R:

Pathophysiological mechanisms of tension-type headache:

a review of epidemiological and experimental studies.

Cephalalgia. 1999, 19:602-21.

10.1046/j.1468-2982.1999.019006602.xChowdhury D:

Tension type headache.

Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2012, 15:S83-8.

10.4103/0972-2327.1000231Bendtsen L:

Central sensitization in tension-type headache—

possible pathophysiological mechanisms.

Cephalalgia. 2000, 20:486-508. 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2000.00070.xSubramanian PS, Barton JJ, Ranalli P, Smith C, Francis CE, Frishberg B:

Consensus statement on visual rehabilitation in

mild traumatic brain injury.

Neurol Clin Pract. 2022, 12:422-8.

10.1212/CPJ.0000000000200071Ailani J, Burch RC, Robbins MS:

The American Headache Society consensus statement: update on

integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice.

Headache. 2021, 61:1021-39.

10.1111/head.14153Jackson JL, Mancuso JM, Nickoloff S, Bernstein R, Kay C:

Tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressants for the prevention of frequent

episodic or chronic tension-type headache in adults:

a systematic review and meta-analysis.

J Gen Intern Med. 2017, 32:1351-8.

10.1007/s11606-017-4121-zGrönkvist R, Vixner L, Äng B, Grimby-Ekman A:

Measurement error, minimal detectable change, and minimal clinically

important difference of the short form-36 health survey, hospital

anxiety and depression scale, and pain numeric rating scale

in patients with chronic pain.

J Pain. 2024, 25:104559.

10.1016/j.jpain.2024.104559

Return to CHRONIC TENSION HEADACHE

Since 10-13-2025

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |