Expert Consensus on a Standardised Definition and Severity

Classification for Adverse Events Associated with Spinal

and Peripheral Joint Manipulation and Mobilisation:

Protocol for an International E-Delphi StudyThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: BMJ Open 2021 (Nov 11); 11 (11): e050219 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Martha Funabashi, Katherine A Pohlman, Lindsay M Gorrell, Stacie A Salsbury, Andrea Bergna, Nicola R Heneghan

Division of Research and Innovation,

Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College,

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

FROM: Nature Scientific Reports 2023Introduction: Spinal and peripheral joint manipulation (SMT) and mobilisation (MOB) are widely used and recommended in the best practice guidelines for managing musculoskeletal conditions. Although adverse events (AEs) have been reported following these interventions, a clear definition and classification system for AEs remains unsettled. With many professionals using SMT and MOB, establishing consensus on a definition and classification system is needed to assist with the assimilation of AEs data across professions and to inform research priorities to optimise safety in clinical practice.

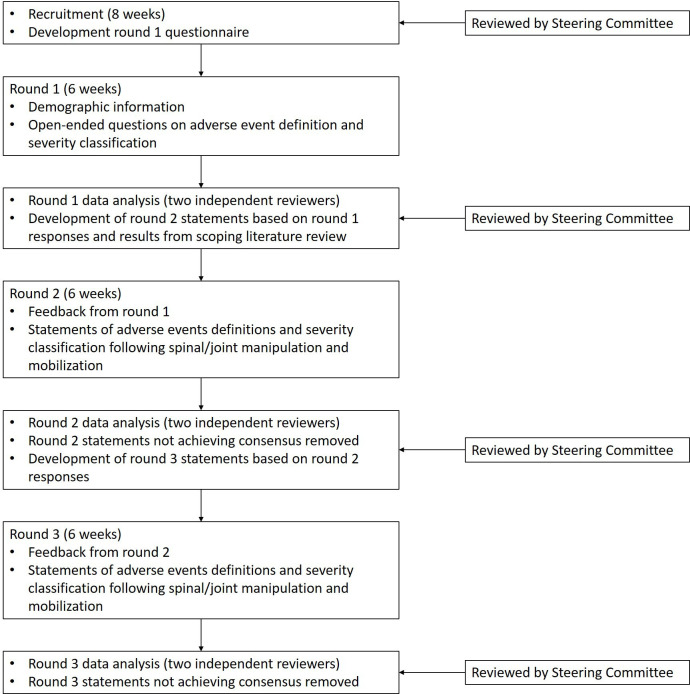

Methods and analysis: This international multidisciplinary electronic Delphi study protocol is informed by a scoping review and in accordance with the 'Guidance on Conduction and Reporting Delphi Studies'. With oversight from an expert steering committee, the study comprises three rounds using online questionnaires. Experts in manual therapy and patient safety meeting strict eligibility criteria from the following fields will be invited to participate: clinical, medical and legal practice, health records, regulatory bodies, researchers and patients. Round 1 will include open-ended questions on participants' working definition and/or understanding of AEs following SMT and MOB and their severity classification. In round 2, participants will rate their level of agreement with statements generated from round 1 and our scoping review. In round 3, participants will rerate their agreement with statements achieving consensus in round 2. Statements reaching consensus must meet the a priori criteria, as determined by descriptive analysis. Inferential statistics will be used to evaluate agreement between participants and stability of responses between rounds. Statements achieving consensus in round 3 will provide an expert-derived definition and classification system for AEs following SMT and MOB.

Ethics and dissemination: This study was approved by the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College Research Ethics Board and deemed exempt by Parker University's Institutional Review Board. Results will be disseminated through scientific, professional and educational reports, publications and presentations.

Keywords: adverse events; complementary medicine; health & safety.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study protocol is based on a formal scoping review of the literature and the published ‘Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES)’.

Researchers will represent all professional groups who perform spinal and peripheral joint manipulation and mobilisation as part of routine clinical practice.

Participants will involve international and multidisciplinary spinal and peripheral joint manipulation and mobilisation stakeholder representatives.

Definitions and a priori criteria for consensus, agreement and stability are detailed.

Findings will be specific to spinal and peripheral joint manipulation and mobilisation, limiting the external validity to other manual therapy techniques.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Spinal and peripheral joint manipulation and mobilisation are interventions commonly used in the management of many musculoskeletal conditions, including spinal pain, and are most often administered in ambulatory care settings. [1, 2] These interventions, which are described in many ways, include among others, high-velocity low-amplitude manipulation, low-velocity variable-amplitude mobilisation, spinal manipulative therapy, musculoskeletal manipulation, osteopathic manipulative treatment, Maitland mobilisation grades, and so on. While both interventions are applied to spinal or peripheral joints, an important distinction is that manipulation usually consists of the application of a dynamic high-velocity, low-amplitude thrust, whereas mobilisation consists of the application of a cyclic low-velocity and variable amplitude manual force. [3] For the purpose of this manuscript, ‘SMT’ will be used to refer to manipulative therapy and ‘MOB’ will be used to refer to mobilisation.

With increasing evidence supporting the effectiveness of SMT and MOB to reduce pain and improve function in patients with musculoskeletal conditions, [4–6] the use of these interventions by patients have also increased. [1] However, research that demonstrates the safety of these approaches has lagged behind efforts to establish the efficacy of these interventions.

Patient safety is a top priority within healthcare and generally focuses on minimising preventable and/or unexpected adverse events following any type of intervention, including SMT and MOB. [7, 8] Despite this awareness, efforts to reduce adverse events within the SMT and MOB fields have been minimal. [7, 9–11] In 2015, a National Patient Safety Foundation expert panel emphasised that patient safety was still a major public health issue. [12] Their key recommendation included the creation of a common set of safety metrics that reflect meaningful outcomes and focused on ambulatory care centres; patient contact in such sites is substantially higher than those located in hospital settings (1 billion annual visits vs 35 million annual admissions, respectively). [13]

While hospital inpatients are expected to have more adverse events due to their acute condition and undergoing more invasive procedures, [14] it is still important to collect adverse events data following SMT interventions in a standardised way. [15] Similar to other healthcare interventions, adverse events after SMT and MOB have been reported. Adverse events attributed mostly to SMT present great variation, ranging from frequent and expected minor adverse events (such as mild discomfort and increased muscle soreness after treatment) to rare and serious adverse events (such as cauda equina syndrome). [10, 16–18] An accurate estimation of the incidence of adverse events following SMT and MOB remains challenging for several reasons, including the varied definitions of what constitutes an adverse event, and the use of diverse terminology. [19] Specifically, ‘adverse events’, ‘adverse reactions’, ‘complications’ and ‘side-effects’ have been used interchangeably in studies reporting unintended and undesirable outcomes following SMT. [20–23] Similarly, ‘mild’, ‘minor’ and ‘benign’, as well as ‘major’, ‘severe’ and ‘intense’ have been used to classify the severity of such events. [24–26] The use of such diverse terminology precludes not only the accurate estimation of adverse events following SMT and MOB, but also advancements of patient safety.

To address these concerns, the systematic evaluation and reporting of adverse events following SMT and MOB would significantly facilitate a better understanding of such events and potentially allow for the development of strategies to prevent and manage their occurrence. More specifically, this standardisation includes the operational definition of what constitutes an adverse event and the severity classification system for similar modalities. By establishing consensus on the definition and the use of a standardised severity classification system, adverse event reports following SMT and MOB can then be better identified and put into the same frame of reference across professions. This has the potential to significantly advance the knowledge related to adverse events, promoting a fundamental advancement in patient safety and quality of care for SMT and MOB.

Aims

The aim of this Delphi study is to determine, by an expert consensus process, a standardised definition and severity classification for adverse events following SMT and MOB, within an adult population with musculoskeletal conditions, for use in both clinical care and research studies.

Methodology

Design and justification

The electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) method is suited to achieving consensus among experts through the independent completion of sequential questionnaires that are refined by participant feedback resulting in a convergence of opinion and eventual consensus. [27] An e-Delphi method in this instance overcomes barriers to other consensus approaches, for example, nominal group technique, differences in geographical location, time zones, and so on. This method therefore allows us to approach experts globally and without limits to specific participant groups.

Figure 1 This protocol has been informed by a rigorous scoping review of the literature (in preparation), is in accordance with the ‘Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES)’ [28] and was registered at Open Science Framework (osf.io/ex3ha). This protocol is also being published a priori to ensure quality, rigour and transparency. Our three-round e-Delphi procedure is outlined in Figure 1 with data collection taking place between November 2021 and June 2022. Using the Research Electronic Data Capture system (REDCap) platform, all rounds will be completed electronically and confidentially. In round 1, participants will be invited to answer open-ended questions on their working definition and/or understanding of adverse events and their current severity classification for SMT and MOB. In round 2, participants will rate their level of agreement with statements generated from round 1 and results from the scoping review of the literature using a 5–point Likert scale. In round 3, participants will rerate their agreement with statements that achieved consensus in round 2. Statements reaching consensus must meet the a priori criteria at rounds 2 and 3.

Expert eligibility and sample

Table 1 Experts will be defined as adult individuals with a high level of knowledge within the area of patient safety and adverse events related to SMT and MOB for musculoskeletal conditions which will be confirmed using the eligibility criteria (see Table 1). Potentially eligible participants will be identified through existing professional networks and social media/internet-based searching. They will be recruited worldwide and be aged 18 or above, able to read and write in English, and willing to provide signed informed consent. Through email, potential participants will be invited to participate by an author or via their professional network connection. Recruitment will be maximised by encouraging identified experts to snowball the invitation with other potential expert participants, including calls for expressions of interest on social media and professional organisations and networks. While expressing their interest in participating in this study on a REDCap electronic form, potential participants will be asked to provide eligibility information.

Informed consent will be obtained electronically through REDCap. Recruitment will continue for 8 weeks with a reminder email sent at weeks 2, 4 and 6. Should no contact be made after 8 weeks, no further communication will be sent. [29]

Sample size in previously published Delphi studies and expert panels have ranged from 4 to 3000. [30] Previous Delphi studies with an aim of defining intervention adverse events and complications typically achieved consensus with responses from 30 to 73 [31–34] experts in the final round and therefore a conservative estimate of 75 responses are required. Assuming a response rate of 70%, a minimum of 108 experts are required to complete the consent form to ensure at least 75 responses. [27] To prevent over representation from one expert group or profession, expressions of interest from potential participants and their eligibility information will be monitored and, to achieve similar number of responses between all professions and groups, additional invitations will be sent to expert groups or professions who are underrepresented.

ProcedureRound 1 The objectives of round 1 are to collect participant demographic information and generate statements on the definition and severity classification of adverse events following SMT and MOB. Participants will complete the ‘Demographic Information Form’ specific to their expert group (ie, researcher, manual therapy clinician, patient, medical doctor, student, professional regulatory body, malpractice insurance and informatics/electronic health records representatives, lawyers and judges; online supplemental file 1). The round 1 questionnaire will consist of open-ended questions. Open-ended questions improve content validity as statements are generated by expert opinion. [27, 35, 36] Statements based on the results of the scoping literature review will be generated and included in round 2, rather than round 1, to allow participants to provide their expert opinion without bias from the literature, thereby reducing experimenter bias. [37] The round 1 questions will ask participants to define their current understanding of adverse events and their severity classification following SMT and MOB. This may or may not include providing references or resources to support their definition or classification. Participants will have the opportunity to provide general comments related to this topic at the end of the questionnaire. The round 1 questionnaire will be piloted for feedback on readability, relevance and appropriateness through selected Delphi expert methodologists in the steering committee and edited accordingly. Round 1 will be open for 6 weeks with email reminders being provided at weeks 1, 3 and 5.

Round 2 The objectives of round 2 are to evaluate consensus of statements developed from the round 1 questionnaire and scoping review findings regarding adverse event definitions and their severity classification following SMT and MOB in adults with musculoskeletal conditions, and to identify any further statements. A detailed description of the scoping review is currently under preparation. Briefly, a literature search strategy was developed with assistance of a health sciences librarian and comprised of combinations of indexing terms (MESH and non-MESH), such as musculoskeletal manipulation, adverse event and definition or classification. Databases, such as Medline, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health (CINAHL) and Scopus were searched as well as grey literature and theses and dissertations. Relevant studies were identified and definition and classification of adverse events following after SMT and MOB were extracted.

Participants will be provided with feedback explaining how statements were generated from round 1 and the scoping review and then asked to rate their agreement with the provided statements using a 5–point Likert scale where 1=strongly disagree and 5=strongly agree. [38] A 5–point scale is preferred as it displays acceptable psychometric properties while being quick and easy for participants to complete, thus reducing frustration and demotivation. [39] An open text box will be included for each statement to allow for any additional comments that may generate further statements. All comments will be analysed by the executive committee and reviewed by selected Delphi expert methodologists in the steering committee. All participants will be invited to take part in round 2, including those who did not complete round 1, provided they have not withdrawn from the study. This provides the opportunity for participants to continue their involvement even when unable to complete previous rounds. [27] As per round 1, the round 2 questionnaire will remain active for 6 weeks with email reminders sent at weeks 1, 3 and 5.

Round 3 The objective of round 3 is to further evaluate statements regarding adverse events definitions and their severity classification following SMT and MOB. The round 3 questionnaire will include feedback from round 2 using descriptive statistics and qualitative comments, promoting participant reflection before completing the questionnaire. In round 3, participants will be asked to rate their agreement with the statements achieving consensus from round 2 using the same 5–point Likert scale. Statements that do not achieve consensus in round 2 will be discarded. A free-text box will be provided for participants to clarify responses, but the generation of new statements will not be encouraged. All responses will be analysed by the executive committee and reviewed by the full steering committee. All participants will be invited to participate in round 3, which will again remain active for 6 weeks with email reminders sent at weeks 1, 3 and 5.

Data analysis

Table 2 Quantitative data analysis will be conducted using R: A language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Qualitative data analysis will be conducted using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, USA). Qualitative data will be analysed independently by two researchers (MF/LG) at each round and disagreements will be resolved by discussion and consensus with the consultation of a third reviewer (KP), if needed.

Complete agreement between executive committee members is required for statements to be included, with disagreements resolved by discussion. [40] The selected Delphi expert methodologists in the steering committee will have the opportunity to review the data and interpretation of findings at each stage for feedback and editing before dissemination to the e-Delphi participants for the next round.Round 1 Qualitative data from open-ended questions will be examined using a theoretical thematic analysis to generate statements under themes preidentified from the scoping review of the literature and then examined inductively for any new themes. [41, 42] Wording used by participants will be combined to generate statements that best represent similar statements across participants. [37] Statements generated from the results of the scoping review of the literature not identified from participant responses will also be included. For a statement to be included, it must be described at least once by any participant or via results of the scoping review of the literature; therefore, all standalone statements will be kept and included. The round 2 questionnaire will be constructed using the statements generated.

Round 2 Descriptive and inferential statistics will be used to evaluate agreement and consensus (Table 2). Statements nearly achieving the a priori criteria for consensus will be reviewed on a case-by-case basis and where appropriate, revised statements based on comments from participants will be carried forward to the next round. Qualitative data from comments will be analysed using thematic analysis for the emergence of any new statements.

Round 3 Descriptive and inferential statistics will evaluate consensus against a priori criteria (median ≥3.5; IQR ≤1 and percentage agreement ≥70%; table 2). Statements achieving consensus after round 3 will be used to define adverse events and their severity classification following SMT and MOB. Statements that fail to achieve consensus in round three will be discarded.

Consensus, agreement and stability

Definitions and statistical measures of consensus and agreement described in the literature for Delphi studies are conflicting. [40, 43–45] Specifically, while consensus and agreement have been used interchangeably, [45] unique definitions have also been recommended. [46] Therefore, this study will use the following definitions and is consistent with earlier research [47]:

Consensus — the extent to which the group of experts share the same opinion. [45]

Agreement — a measure of inter-rater agreement where the rating of one expert can be predicted by the rating of another. [47]

Stability — the consistency of responses between successive rounds. [45]

For each round, a combination of descriptive and inferential statistics will be used to assess consensus, agreement and stability (Table 2). [40, 43, 44, 47] Consensus will be evaluated using descriptive statistics of central tendency and dispersion (median and IQR). Percent agreement of responses rated agree/strongly agree will also be used to evaluate consensus for each statement. [49] To enable convergence and strengthen consensus overall criteria will be increased between rounds 2 and 3.49 Kendall’s Coefficient of Concordance (W) where 0 is no agreement and 1 is perfect agreement will be used to evaluate agreement across all items and within categories identified after round 1.48 Wilcoxon rank-sum test will be used to evaluate stability of the responses between rounds 2 and 3.45 Statistical significance will be set at p<0.05.

Data management

All data will be managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools, [50] which is hosted at Parker University, Dallas, Texas, USA. REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies. All personal information and data will be kept secure from any third party using a password-protected computer during the study. Only members of the study team will have access to the study data. On completion of the study, the data will be kept securely for 10 years at Parker University, Dallas, Texas, USA, before being securely destroyed in accordance with the institution’s guidelines.

Study executive committee

Table 3 The executive committee is composed of international and multidisciplinary members with expertise in patient safety and SMT and MOB (Table 3). This committee will lead and conduct this study. Tasks include questionnaire development; management of data collection and questionnaire completion; compilation and summarising results at each round; proposal of additional statements; and preparing reports of final results, such as summary of findings infographic and manuscripts for publication.

Study steering committee

The steering committee is composed of international and multidisciplinary members with expertise in patient safety, methodology, and SMT and MOB (Table 3). Members in this committee will aid in expert participant identification and either provide their opinions and expertise through (1) being a participant in the Delphi panel, or (2) providing feedback on questionnaire development, structure and clarity, reviewing study results at each round and approving additional statement inclusion and review study conduct (selected Delphi expert methodologists mentioned in Methods section). Feedback and changes suggested by the steering committee members must be approved by the executive committee before implementation. At the end of round 3, all steering committee members will aid in the interpretation of final results and dissemination of findings.

Patient and public involvement

The study was conceived from our experience working with clinicians and patients using SMT and MOB and their views were used to highlight the relevance of this research. Our steering committee will include a patient representative who will codesign the ‘Participant Information Sheets’, expression of interest emails/social media posts and developing the round 1 questionnaire. It is anticipated that our patient representative will also contribute to reviewing results at each round and support interpretation of findings. Our patient representative will be central to our dissemination strategy including patient cohorts. A summary of results will be disseminated to all professions through professional organisations newsletter, conferences and reports. Feedback from professional groups will be invited to inform future studies and to facilitate the ongoing collaboration of an international, multidisciplinary research working group to support advancement of knowledge in the field of adverse events. Patient and public involvement in the full study will be reported using the ‘Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public2-short form (GRIPP2-SF)’51 when disseminating the study results.

Discussion

This e-Delphi study will provide expert consensus on the definition of adverse events and their severity classification following SMT and MOB that could not be determined from the current literature. In this study, we will use the term ‘adverse event’ in accordance with previous studies in this area,24 25 but consider it an umbrella term representative of other related terms referring to undesirable outcomes of SMT and MOB, such as ‘harms’, ‘complications’, ‘side effects’, etc.

Conducting a Delphi study electronically allows the development of expert informed recommendations from a wide range of specialists, regardless of geographical location, and who can participate confidentially, which is considered a strength. Another noticeable strength of this study is the active participation and collaboration of several professions that routinely perform SMT and MOB when treating patients with musculoskeletal conditions (ie, chiropractic, naprapathy, physiotherapy and osteopathy). Inclusion of international and multidisciplinary experts will ensure that the unique views and opinions of each profession and expert group is taken into consideration, while creating a standardised definition of adverse events and severity classification. Critically establishing standardised definitions and severity classifications across professions will significantly advance the evidence concerning adverse events. Drawing on a single expert multi-professional framework will contribute to enhancing the consistency in recording adverse events and will, in time, improve our understanding of the adverse events following SMT and MOB. From this, strategies to prevent and mitigate such events may be developed, which can significantly increase the knowledge related to adverse events, promoting a fundamental advancement in patient safety and quality of care for all professions that use SMT and MOB.

Ethics and dissemination

This study was approved by the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College Research Ethics Board (#2103B01) and deemed exempt by Parker University’s Institutional Review Board (A-00218). Freely given e-informed consent will be obtained from all participants prior to participation through REDCap. Participants will be informed of the withdrawal process and assured anonymity throughout the study and during dissemination. Results from this study will be disseminated through scientific, professional and educational reports, publications and presentations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary File 1: (443K, pdf)

Reviewer comments: (443K, pdf)

Author's manuscript: (1.7M, pdf)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the clinical, methodological and patient experts who have agreed to be members of the study steering committee and are ensuring rigour and quality of this study. We specifically acknowledge the following members of the steering committee for their assistance with this protocol development: Christopher Burrell, Anita Gross, Steven Vogel and Silvano Mior.

Contributors:

MF, KAP, LMG, AB and NRH are leading the protocol development, analyses and dissemination.

Data analysis will be completed independently by MF and LMG with oversight by KAP, AB and NRH.

SAS is a member of the steering committee overseeing protocol development and made significant contributions to this manuscript.

All authors and steering committee members will be involved in interpretation of the findings and dissemination strategy.

All authors have contributed to the design and development of the protocol and have contributed to the manuscript draft.

All authors have read, provided feedback and approved the final manuscript.

Funding:

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References:

Hurwitz, EL.

Epidemiology: Spinal Manipulation Utilization

J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2012 (Oct); 22 (5): 648–654Beliveau PJH, Wong JJ, Sutton DA, Simon NB, Bussieres AE, Mior SA, et al.

The Chiropractic Profession: A Scoping Review of Utilization Rates,

Reasons for Seeking Care, Patient Profiles, and Care Provided

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2017 (Nov 22); 25: 35Rushton K, Ronel B, Jordaan JL.

Educational standards in orthopaedic manipulative therapy, 2016. Available:

http://www.ifompt.org/site/ifompt/IFOMPTStandardsDocumentdefinitive2016.pdfCoulter ID, Crawford C, Hurwitz EL, Vernon H, Khorsan R, Suttorp Booth M, Herman PM.

Manipulation and Mobilization for Treating Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Spine J. 2018 (May); 18 (5): 866–879Paige NM, Myiake-Lye IM, Booth MS, et al.

Association of Spinal Manipulative Therapy with Clinical Benefit and Harm

for Acute Low Back Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

JAMA. 2017 (Apr 11); 317 (14): 1451–1460Clar C, Tsertsvadze A, Court R, Hundt G, Clarke A, Sutcliffe P.

Clinical Effectiveness of Manual Therapy for the Management of

Musculoskeletal and Non-Musculoskeletal Conditions:

Systematic Review and Update of UK Evidence Report

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2014 (Mar 28); 22 (1): 12Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson M, eds.

To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System

Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine (Nov 1999)WHO (World Health Organization)

Towards Eliminating Avoidable Harm in Health Care

Draft Global Patient Safety Action Plan 2021-2030, 2021.Landrigan CP, Parry GJ, Bones CB, et al.

Temporal trends in rates of patient harm resulting from medical care.

N Engl J Med 2010;363:2124–34Swait G, Finch R.

What Are the Risks of Manual Treatment of the Spine?

A Scoping Review for Clinicians

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2017 (Dec 7); 25: 37Vohra S, Kawchuk GN, Boon H, et al.

SafetyNET: an interdisciplinary research program to support a

safety culture for spinal manipulation therapy.

Eur J Integr Med 2014;6:473–7.Foundation NPS .

Free from harm: accelerating patient safety improvement fifteen years after to err is human 2015.Statistics NC for H .

FastStats A to Z, 2015. Available:

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/Marra AR, Algwizani A, Alzunitan M, et al.

Descriptive epidemiology of safety events at an academic medical center.

Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:353Kuriakose R, Aggarwal A, Sohi RK, et al.

Patient safety in primary and outpatient health care.

J Family Med Prim Care 2020;9:7–11.Funabashi M, Pohlman KA, Goldsworthy R, et al.

Beliefs, perceptions and practices of chiropractors and patients about

mitigation strategies for benign adverse events after spinal manipulation therapy.

Chiropr Man Therap 2020;28:46Carnes D, Mars TS, Mullinger B, et al.

Adverse events and manual therapy: a systematic review.

Man Ther 2010;15:355–63.Hebert JJ, Stomski NJ, French SD, et al.

Serious Adverse Events and Spinal Manipulative Therapy

of the Low Back Region: A Systematic Review of Cases

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2015 (Nov); 38 (9): 677–691Pohlman KA, Funabashi M, Ndetan H, et al.

Assessing adverse events after chiropractic care at a chiropractic

teaching clinic: an Active-Surveillance pilot study.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2020;43:845–54.Senstad O, Leboeuf-Yde C, Borchgrevink CF.

Side-Effects of chiropractic spinal manipulation: types frequency,

discomfort and course.

Scand J Prim Health Care 1996;14:50–3.Walker, BF, Hebert, JJ, Stomski, NJ et al.

Outcomes of Usual Chiropractic.

The OUCH Randomized Controlled Trial of Adverse Events

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013 (Sep 15); 38 (20): 1723–1729Rubinstein, S.M.

Adverse Events Following Chiropractic Care for Subjects With Neck

or Low-Back Pain: Do The Benefits Outweigh the Risks?

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008 (Jul); 31 (6): 461–464Carlesso LC, Macdermid JC, Santaguida LP.

Standardization of adverse event terminology and reporting in orthopaedic

physical therapy: application to the cervical spine.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2010;40:455–63Carnes D, Mullinger B, Underwood M.

Defining adverse events in manual therapies: a modified Delphi consensus study.

Man Ther 2010;15:2–6Pohlman KA, Beirne MO, Thiel H, Cassidy JD, Mior S, Hurwitz EL, et al.

Development and Validation of Providers’ and Patients’

Measurement Instruments to Evaluate Adverse Events

After Spinal Manipulation Therapy

Eur J Integr Med. 2014 (Aug); 6 (4): 451–466Eriksen K, Rochester RP, Hurwitz EL.

Symptomatic reactions, clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction

associated with upper cervical chiropractic care: a prospective, multicenter, cohort study.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011;12:219. 10.1186/1471-2474-12-219Keeney S, Hasson F, Mckenna H.

The Delphi technique in nursing and health research.

Wiley-Blackwell, 2010Jünger S, Payne SA, Brine J, et al.

Guidance on conducting and reporting Delphi studies (CREDES) in palliative care:

recommendations based on a methodological systematic review.

Palliat Med 2017;31:684–706.Delbecq A, Van de Ven A, Gustafson D.

Group techniques for program planning; a guide to nominal group and Delphi processes.

Glenview, IL: Scott Foresman and Company, 1975Cantrill JA, Sibbald B, Buetow S.

The Delphi and nominal group techniques in health services research.

Int J Pharm Pract 2011;4:67–74Carnes D, Mullinger B, Underwood M.

Defining adverse events in manual therapies: a modified Delphi consensus study.

Man Ther 2010;15:94–8Kranenburg HA, Lakke SE, Schmitt MA, et al.

Adverse events following cervical manipulative therapy: consensus on

classification among Dutch medical specialists, manual therapists, and patients.

J Man Manip Ther 2017;25:279–87Rosenthal R, Hoffmann H, Clavien P-A, et al.

Definition and classification of intraoperative complications (classic):

Delphi study and pilot evaluation.

World J Surg 2015;39:1663–71Audigé L, Schwyzer H-K, et al.

Shoulder Arthroplasty Core Event Set (SA CES) Consensus Panel .

Core set of unfavorable events of shoulder arthroplasty:

an international Delphi consensus process.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2019;28:2061–71Dalkey N, Helmer O.

An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts.

Manage Sci 1963;9:458–67.Goodman CM.

The Delphi technique: a critique.

J Adv Nurs 1987;12:729–34.Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H.

Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique.

J Adv Nurs 2000;32:1008–15.Zambaldi M, Beasley I, Rushton A.

Return to play criteria after hamstring muscle injury in professional football:

a Delphi consensus study.

Br J Sports Med 2017;51:1221–6.Preston CC, Colman AM.

Optimal number of response categories in rating scales:

reliability, validity, discriminating power, and respondent preferences.

Acta Psychol 2000;104:1–15de Loë RC, Melnychuk N, Murray D, et al.

Advancing the state of policy Delphi practice: a systematic review evaluating

methodological evolution, innovation, and opportunities.

Technol Forecast Soc Change 2016;104:78–88.Braun V, Clarke V.

Successful qualitative research: a practical guide for beginners.

SAGE Publications, 2013.

https://books.google.com/books?id=EV_Q06CUsXsC&pgis=1Braun V, Clarke V.

Using thematic analysis in psychology.

Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101.Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, et al.

Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare

quality indicators: a systematic review.

PLoS One 2011;6:e20476Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, et al.

Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria

for reporting of Delphi studies.

J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:401–9von der Gracht HA.

Consensus measurement in Delphi studies: review and implications

for future quality assurance.

Technol Forecast Soc Change 2012;79:1525–36.Meijering JV, Kampen JK, Tobi H.

Quantifying the development of agreement among experts in Delphi studies.

Technol Forecast Soc Change 2013;80:1607–14.Price J, Rushton A, Tyros V, et al.

Consensus on the exercise and dosage variables of an exercise training programme

for chronic non-specific neck pain: protocol for an international e-Delphi study.

BMJ Open 2020;10:e037656Schmidt RC.

Managing Delphi surveys using nonparametric statistical techniques.

Decision Sciences 1997;28:763–74Wiangkham T, Duda J, Haque MS, et al.

Development of an active behavioural physiotherapy intervention (ABPI)

for acute whiplash-associated disorder (WAD) II management: a modified Delphi study.

BMJ Open 2016;6:e011764.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al.

Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology

and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support.

J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81.Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, et al.

GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting

of patient and public involvement in research.

BMJ 2017;358:j3453.

Return to ADVERSE EVENTS

Since 11-23-2021

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |