Clinical Course of Non-specific Low Back Pain:

A Systematic Review of Prospective Cohort

Studies Set in Primary CareThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: European Journal of Pain 2013 (Jan); 17 (1): 5–15 ~ FULL TEXT

C.J. Itz, J.W. Geurts, M. van Kleef, P. Nelemans

Department of Health Service Research,

Maastricht University,

Maastricht, The Netherlands.

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVE: Non-specific low back pain is a relatively common and recurrent condition for which at present there is no effective cure. In current guidelines, the prognosis of acute non-specific back pain is assumed to be favourable, but this assumption is mainly based on return to function. This systematic review investigates the clinical course of pain in patients with non-specific acute low back pain who seek treatment in primary care.

DATABASES AND DATA TREATMENT: Included were prospective studies, with follow-up of at least 12 months, that studied the prognosis of patients with low back pain for less than 3 months of duration in primary care settings. Proportions of patients still reporting pain during follow-up were pooled using a random-effects model. Subgroup analyses were used to identify sources of variation between the results of individual studies.

RESULTS: A total of 11 studies were eligible for evaluation. In the first 3 months, recovery is observed in 33% of patients, but 1 year after onset, 65% still report pain. Subgroup analysis reveals that the pooled proportion of patients still reporting pain after 1 year was 71% at 12 months for studies that considered total absence of pain as a criterion for recovery versus 57% for studies that used a less stringent definition. The pooled proportion for Australian studies was 41% versus 69% for European or US studies.

CONCLUSIONS: The findings of this review indicate that the assumption that spontaneous recovery occurs in a large majority of patients is not justified. There should be more focus on intensive follow-up of patients who have not recovered within the first 3 months.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Non-specific low back pain (LBP) is a relatively common and recurrent condition with major medical and economical implications for which today there is no effective cure (van Tulder et al., 1995; Roelofs et al., 2008; Becker et al., 2010; van Middelkoop et al., 2011). Most treatment strategies and guidelines are based on the assumption that the prognosis of acute LBP is favourable and that the pain resolves spontaneously in the majority of patients (Spitzer et al., 1987; Andersson, 1999; van Tulder et al., 2006). However, the evidence for this statement is mainly based on occupational studies in which ‘return to work’ or ‘recovery from disability’ is studied (Spitzer et al., 1987; Croft et al., 1998; Andersson, 1999). These studies indicate that most back pain patients return to function, this in spite of their pain (Bowey-Morris et al., 2011). There seems to be a lack of information on the course of acute non-specific LBP when pain rather than return to work is considered as endpoint.

A previous systematic review that assessed the prognosis of acute LBP found high rates of LBP after 1 year of follow-up (42% to 75%) (Hestbaek et al., 2003). However, this aforementioned review did not evaluate the clinical course by providing information on proportions of patients with early onset of LBP and also included studies that were not performed in primary care settings.

The present review is designed to investigate the clinical course of pain in patients with non-specific LBP of less than 3 months of duration, with a follow-up of at least 12 months, and set in primary care.

Database This systematic review investigates the clinical course of low back pain in primary care settings. Nonspecific low back pain is a relatively common and recurrent condition for which at present there is no effective cure. In current guidelines the prognosis of acute nonspecific back pain is assumed to be favourable but this assumption is mainly based on return to function. Included were 11 prospective studies, with follow-up of at least 12 months, which studied the prognosis of patients with back pain for less than 3 months of duration set in primary care.

What does this review add? This review shows that after 3 months recovery is observed in 33% and after one year 65%

Methods

Study selection

Table 1 A literature search was performed for suitable articles published between 1990 and 2010 in English, German and Dutch, referenced on MEDLINE and PUBMED, and EMBASE (Table 1). The search was started at 1990 because in 1987 Spitzer wrote his monograph: Scientific approach to the assessment and management of activityrelated spinal disorders. A monograph for clinicians. Report of the Quebec Task Force on Spinal Disorders (Spitzer et al., 1987). This study had a major impact on the treatment of LBP, and still has impact today. Therefore, we were basically interested in evidence provided by studies that were published in the years following this publication.

The following keywords were used: LBP and sciatica, follow-up and prognosis, onset or inception cohort, acute or sub-acute. Two authors (C.I. and J.G.) independently screened the titles, abstracts and keywords of all references identified by the literature search to determine if they addressed the research question. Full-text publications were retrieved for potentially relevant articles. The bibliographies of the retrieved articles were screened for additional relevant papers.

Studies were considered eligible for review if they allowed for evaluation of the clinical course of nonspecific LBP and met the following inclusion criteria:(1) the study was prospective in design (prospective cohort study or controlled trial);

(2) the study population consisted of adult patients with non-specific LBP;

(3) patients were included within 3 months after LBP onset with follow-up data of at least 1 year;

(4) one of the study outcomes was pain and the proportion of patients with or without pain could be extracted from the study or could be established after contacting the (corresponding) author;

(5) the patients were recruited in primary care settings; and

(6) data were available from patients who did not undergo an intervention or from patients who underwent an intervention that was reported not to affect the pain scores.Studies were excluded if:

(1) the study population included patients with trauma, surgery and/or injury; and

(2) the selection of patients was restricted to special work conditions or pregnant women.When multiple studies were identified with overlap in study populations, only the original study was included to avoid potential duplication of datasets.

Data extraction

Two authors (C.I. and J.G.) independently extracted data from selected studies on proportion of pain and relevant population and study characteristics. The main study parameter is the proportion of patients with pain at 12 months. Other parameters of interest were proportions of patients with pain at 1, 3 and 6 months. In cases where absolute numbers of patients with pain at 12 months could not be derived from the publication and/or the definition of recovery from pain was unclear, the authors were contacted for additional information.

Study characteristics considered of interest were: sample size; country where the study was performed; year of publication; percentage of male participants; mean age; definition and localization of LBP; mean time since onset; and definition of recovery from pain. Items concerning representativeness of the target population such as response and dropout rates during follow-up were also recorded.

Quality assessment

Table 2

Table 3 For assessment of the quality of the articles modified, Leboeuf criteria were used (Leboeuf-Yde and Lauritsen, 1995) (Table 2). This method uses criteria related to the representativeness of the study sample, the quality of data and the definition of LBP. An additional item concerning analysis of data (item E) was added. The authors (C.I. and J.G.) independently scored these items. In cases of disagreement, discrepancies were discussed with a third author (P.N.) and consensus was achieved. Each study was assigned a score, expressed as a proportion of fulfilled criteria out of the total number of relevant criteria. Information provided in the published report of the study was scored as present (+ criterion fulfilled), absent (– criterion not fulfilled) or 'not applicable' (NA) (Table 3). If the study design appeared to allow for the omission of a certain criterion, it was noted as methodologically acceptable (+). The main study parameter for this review was the proportion of patients with pain. Therefore, if data on pain were presented in a way that did not allow for calculation of proportions, the score ‘not applicable’ was used for item E, otherwise it was scored as present (+ criterion fulfilled). For each study, only one of the items G, H and I was scored depending on the method that was used to evaluate presence of pain (questionnaire, interview or examination).

We distinguished between studies with a quality score of >70% versus studies with a score of ≤ 70% to evaluate whether the quality of studies affects the proportion of patients with pain after 1 year. The cutoff point of 70% was arbitrarily chosen.

Data analysis

The primary outcome of interest is the proportion of patients who still suffer from LBP at 1 year after onset. Secondary outcome measures were the proportion of patients with LBP 1, 3 and 6 months after onset.

Proportions of patients with pain at 12 months, and if available at 1, 3 and 6 months, were derived from studies. For each time point, proportions were pooled using random-effects models as proposed by DerSimonian and Laird using the inverse of the standard errors of the proportion of individual studies as weights (DerSimonian and Laird, 1986). The I2 index was used to test for heterogeneity between study results. Significance of this index indicates that differences between studies cannot be solely attributed to sampling variation and that differences in study population, design and analysis are responsible for variation between study results (Higgins et al., 2003).

Subgroup analyses were used to evaluate whether presence or absence of a specific study characteristic is associated with higher or lower pooled proportions of patients with pain at 12 months. For this purpose, studies were categorized into subgroups according to the presence or absence of a specific study characteristic. The differences in pooled proportions between subgroups with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to evaluate the magnitude of effect of the study characteristic on study result and to test the effect for statistical significance.

All analyses were performed with the statistical package STATA (Copyright 2009, StataCorp LP, TX, USA). P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. Graphs were created with either STATA or R (version 2.12.2: http://www.rproject. org/).

Results

Study selection

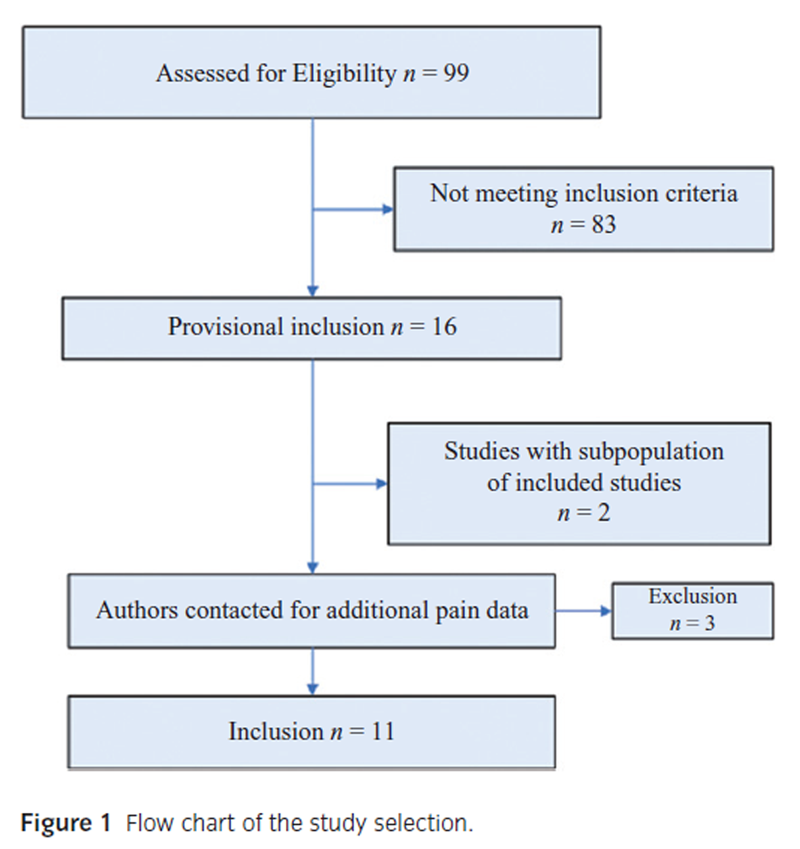

Figure 1 The search strategy identified 99 papers eligible for evaluation. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 83 studies were excluded. Sixteen studies were provisionally included for this systematic review (Figure 1). Two studies in which the population was a subpopulation from an original study, which was already included for this review, were excluded for evaluation (Wahlgren et al., 1997; Costa Lda et al., 2009). The authors of 10 studies were contacted by mail and email to get additional information on proportions of patients with pain at 1 year and, if available, other follow-up time points and the exact definition used for being pain free (Faas et al., 1993; Weber et al., 1993; Dettori et al., 1995; Klenerman et al., 1995; Croft et al., 1998; Epping-Jordan et al., 1998; Burton et al., 1999; Werneke and Hart, 2001; Karjalainen et al., 2003; Grotle et al., 2007). This approach resulted in a total of 11 studies that were finally included for evaluation in this review (Dettori et al., 1995; Klenerman et al., 1995; Croft et al., 1998; Epping-Jordan et al., 1998; Burton et al., 1999; Schiottz-Christensen et al., 1999; McGuirk et al., 2001;Werneke and Hart, 2001; Sieben et al., 2005; Bousema et al., 2007; Henschke et al., 2008).

Characteristics of included studies

In Table 4, the characteristics of the 11 included studies are shown. The number of participants in each study varied between 83 and 973. The percentage of male participants varied between 45% and 100%. The outcome parameter that was considered of primary interest varied largely between the evaluated studies and included pain but also physical activity and function; disability; fear avoidance; and sick leave. Two studies were performed in the United States, two studies in Australia and the remaining seven were European studies.

The anatomical definition of LBP was mostly defined according to localization of the pain; in six studies no definition was stated. The definition of LBP differs between studies, one study defined LBP as pain in the thoracic and lumbar region, other studies formulated LBP as localized ‘between the scapulae and the gluteal folds’, or ‘below thoracic vertebra 6 (T6)’, or ‘between T12 and the buttock crease’.

Different methods and pain scales were used for the evaluation of pain intensity, namely: Visual Analogue Scale (VAS); Numeric Rating Scale; Graded Chronic Pain Scale; and Descriptor Differential Scale; a selfconstructed question about pain/a question about pain specifically constructed for the study (Price et al., 1983; Gracely and Kwilosz, 1988; Von Korff et al., 1992; Childs et al., 2005).

Studies used different cut-off points for classifying patients as free from pain and different periods in which the patient had to be pain free (varying from 1 day to 6 months).

The mean time since onset of LBP varied between 0 and 12 weeks. In many studies, the timing of the follow-up visits was at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months (Table 4). Methodological quality varied between 40% and 90% (Table 3).

Clinical course of LBP

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4 Figure 2 shows the course of acute LBP during follow-up of 1 year according to the pooled proportions of patients with pain at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months. These pooled proportions at 1, 3 and 6 months after onset were 80% (95% CI: 61–100%); 67% (95% CI: 50–83%) and 57% (95% CI: 46–68%), respectively. The pooled proportion of patients with pain 1 year after onset of LBP was 65% (95% CI: 54–75%).

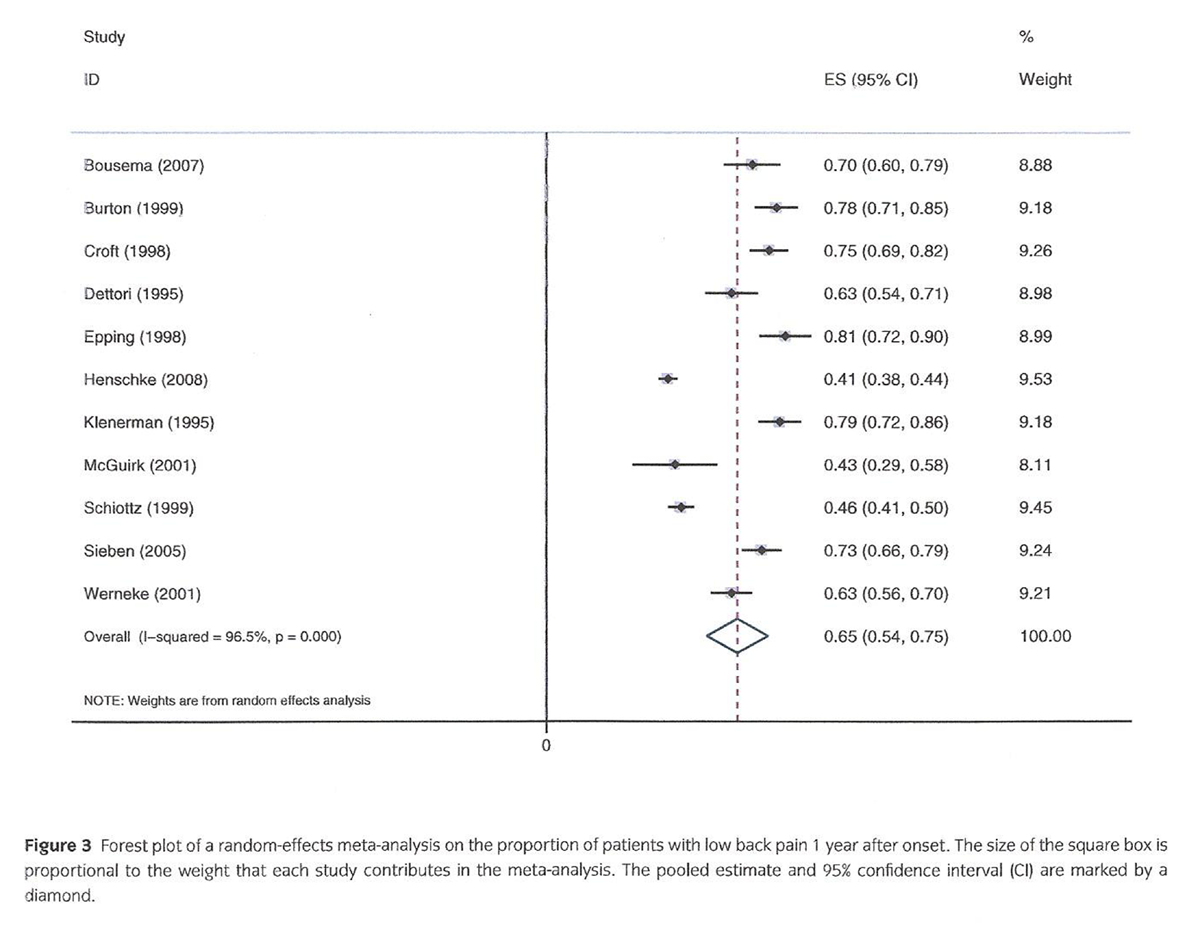

The Forest plot (Figure 3) shows the proportions of patients who still reported pain at 1 year after onset of LBP with 95% CI for the individual 11 studies. The I2 index was 96.5 %, which indicates large heterogeneity of study results.

There are five studies that reported proportions with pain at both 3 and 12 months (Croft et al., 1998; Burton et al., 1999; McGuirk et al., 2001; Sieben et al., 2005; Henschke et al., 2008). All five studies showed that after 3 months there was little additional recovery, namely between 3 and 12 months the percentage of patients still reporting pain decreased by only 1–7%.

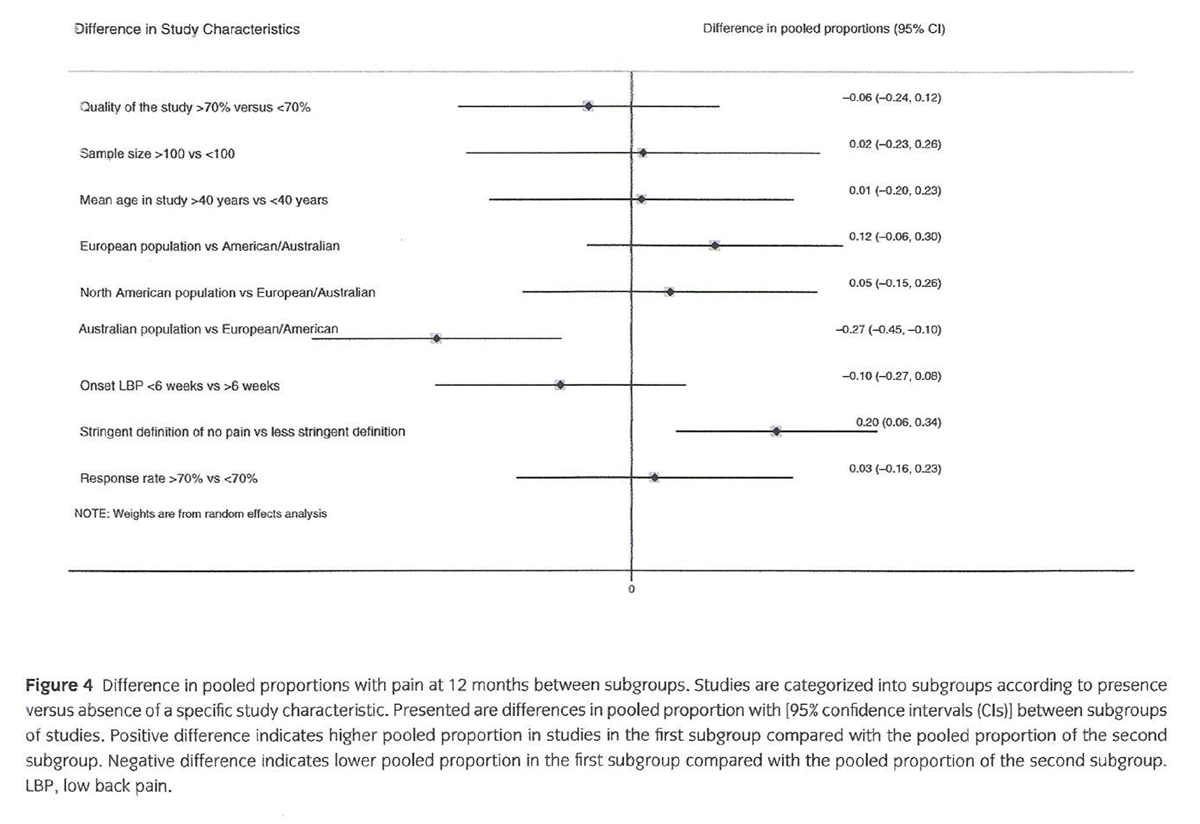

Figure 4 shows the results of subgroup analyses with respect to the effect of pre-specified study characteristics on study results. The pooled proportion of patients with pain at 1 year after onset was significantly lower in two Australian studies than the pooled proportion based on nine studies from Europe or the United States. The pooled proportion of patients with pain at 1 year after onset was significantly lower for studies that used a less stringent definition of recovery from pain, i.e., studies that also considered patients who reported mild pain as being free from pain and studies that used a self-formulated question about pain/a question about pain specifically formulated for the study (Dworkin et al., 2005, 2009).

Discussion

The findings of this review indicate that the majority of patients (65%) still experience pain 1 year after onset of LBP. In the first 3 months, recovery is observed in a substantial part of the patients, but thereafter only few patients recover.

The conclusion of this review is in line with a previous systematic review that questioned the prognosis of acute LBP and also found high rates of LBP after 1 year varying between 42% and 75% (Hestbaek et al., 2003). This review differed from the present review by also including studies that were performed in secondary and tertiary care settings and no restriction to recent onset of acute LBP. Despite the differences, both reviews arrive at similar results. This finding may indicate that in the present review efforts to restrict the study population to patients with early onset of back pain have not been successful. The definition of recent onset LBP is, with a duration of less than 3 months, rather arbitrarily defined and relies heavily on the memory of patients who may feel that their back pain is of recent origin whereas it could have started more than 3 months ago.

The findings in this review are in sharp contrast with current recommendations and guidelines for the treatment of patients with non-specific LBP, which are based on the assumption that in a large majority of patients spontaneous recovery occurs. The European guidelines for acute non-specific LBP cite that acute LBP is usually self-limiting (a recovery rate of 90% within 6 weeks) and only 2–7% of people develop chronic pain, although references to underpin this statement are not provided (van Tulder et al., 2006). The assumption that spontaneous recovery is common resulted in management recommendations that put strong emphasis on reassurance of the patient that rapid recovery is to be expected, limitation of referral to secondary care and continuation of daily activities.

It may be worth considering what may be the basis for this widespread belief that spontaneous recovery is common. One of the reasons may be that in many studies on back pain published during the last 20 years, ‘return to work’ or ‘recovery from disability’ was considered evidence for recovery from LBP (Spitzer et al., 1987; Andersson, 1999). However, this supposition may be criticized as it is quite conceivable that patients may still suffer from pain. Another reason may be that individual studies show variation in results, although none of the reviewed studies reported a recovery rate of 80–90%.

Four larger studies that were included in this review reported that the proportion of patients who are still having pain 1 year after onset varied between 41% and 75%. Therefore, another aim of the present review was to explore reasons for the large variation between studies in pain results. An important source of heterogeneity that was identified was the definition of pain recovery that was used. The subgroup of studies that considered total absence of pain as a criterion for recovery and used a validated pain questionnaire, e.g., the VAS, showed a higher pooled proportion of patients with pain (71%) compared with the studies that used less stringent standards and/or were content with considering low pain scores as indicative of complete recovery (57%). The difference in the pooled proportions is 20% (Fig. 4).

Another interesting finding may be that studies performed in Australia (McGuirk et al., 2001; Henschke et al., 2008) reported more favourable prognosis than the studies from Europe and the United States. The pooled proportion of patients with pain at 12 months was lower in Australian studies than in American/ European studies, with a difference of 27% (Fig. 4). One explanation for this finding could be that the American/European studies generally used a combination of outcome measures regarding LBP. This is in accordance with the IMMPACT recommendations by Dworkin et al. who recommended use of a combination of relevant validated outcome measures to evaluate treatment effectiveness (Dworkin et al., 2005). In the Australian study by McGuirk, only a VAS was used and patients who reported mild pain, with one single pain intensity score from 0 to 10 mm on a VAS from 0 to 100 mm, were considered as being free from pain. The other Australian study by Henschke et al. used only one modified question of the SF36 questionnaire (Henschke et al., 2008) whereas the SF questionnaire was not developed for this purpose.

The results of this and other systematic reviews indicate that the current approach towards management of patients with non-specific LBP calls for reorientation. The paradigm that the prognosis of LBP is mostly favourable can lead to conservatism in pain management and could be contra-productive for innovations in pain treatment. It may have paralysed the need for knowledge about mechanism and causes of back pain and hampered development of further treatment options.

There should be more focus on intensive follow-up and monitoring of patients who have not recovered from pain within 3 months. Pharmacologic treatment and minimally invasive interventions must be considered.

Further research is needed to re-evaluate the concept of non-specific LBP. At present, LBP with unknown cause is diagnosed as non-specific. But it can not be excluded that within this heterogeneous group identification of patients with specific causes is possible. Classification into more specific subgroups could result in more homogeneous groups and help advance development of more pinpointed and specified pain treatment options.

This review has some limitations. First, results are based on published data with a large variation in study results. To account for this heterogeneity, a random-effects model was used, but such a metaanalytic approach has limitations and therefore results from pooling must be interpreted with caution. However, if we had refrained from pooling, the conclusion would still be that pain persists in a substantial proportion of patients, as even studies with conservative estimates indicate that at least 40% of patients are not free from pain after 1 year of follow-up.

Second, for the evaluation of the course of LBP over time, the pooled proportions at consecutive time points were derived from different sets of studies. There were only five studies that reported results at both 3 and 12 months (Croft et al., 1998; Burton et al., 1999; McGuirk et al., 2001; Sieben et al., 2005; Henschke et al., 2008). The pooled proportions of patients with pain from these studies were 67% (50– 83%) and 62% (44–81%) at 3 and 12 months, respectively, and are consistent with the conclusion that one-third of patients recover within the first 3 months and that the majority still report pain at 12 months.

Third, this review provides information on prevalence of pain at longer follow-up, but not on severity of pain. Information on the distribution of pain scores in patients with persisting pain was not provided in detail by the included studies, only one study presented a mean VAS pain score of 26.5 mm in patients who still suffer pain at 12 months of follow-up (Bousema et al., 2007). It is recommended to address this issue in more detail in future studies on clinical course of patients with non-specific acute LBP.

Conclusions

This systematic review shows that spontaneous recovery from non-specific LBP occurs in the first 3 months after onset of LBP in about one-third of patients, but the majority of patients (65%) still experience pain 1 year after onset of LBP. These findings indicate that the assumption underlying current guidelines that spontaneous recovery occurs in a large majority of patients is not justified. There should be more focus on intensive follow-up and monitoring of patients who have not recovered within the first 3 months. Future research should be directed at improvement of classification of non-specific LBP in more specific groups.

Author contributions

Both C.I. and J.G. independently screened the titles, abstracts and keywords of all references identified by the literature search, extracted data from selected studies on population and study characteristics, and assessed the quality of the articles. J.G. corresponded with authors from studies considered for evaluation. Analyses were performed by J.G. and P.N. P.N. and M.v.K. oversaw and contributed to the overall execution of the project. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. All authors helped to write the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The authors like to thank Sander van Kuijk from the Department of Epidemiology of the Maastricht University for his help.

References:

Andersson, G.B. (1999).

Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain.

Lancet 354, 581–585.Becker, A., Held, H., Redaelli, M., Strauch, K., Chenot, J.F., Leonhardt, C., Keller, S. (2010).

Low back pain in primary care: costs of care and prediction of future health care utilization.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010; 35: 1714–1720Bousema, E.J., Verbunt, J.A., Seelen, H.A., Vlaeyen, J.W., Knottnerus, J.A. (2007).

Disuse and physical deconditioning in the first year after the onset of back pain.

Pain 130, 279–286.Bowey-Morris, J., Davis, S., Purcell-Jones, G., Watson, P.J. (2011).

Beliefs about back pain: Results of a population survey of working age adults.

Clin J Pain 27, 214–224.Burton, A.K., Waddell, G., Tillotson, K.M., Summerton, N. (1999).

Information and advice to patients with back pain can have a positive effect. A randomized controlled trial of a novel educational booklet in primary care.

Spine 24, 2484–2491.Childs, J.D., Piva, S.R., Fritz, J.M. (2005).

Responsiveness of the numeric pain rating scale in patients with low back pain.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 30, 1331–1334.Costa Lda, C., Maher, C.G., McAuley, J.H., Hancock, M.J., Herbert, R.D., Refshauge, K.M., Henschke, N. (2009).

Prognosis for patients with chronic low back pain: Inception cohort study.

BMJ 339, b3829.Croft, P., Macfarlane, G., Papageorgiou, A. (1998).

Outcome of low back pain in general practice:

A prospective study

BMJ 1998 (May 2); 316 (7141): 1356–1359DerSimonian, R., Laird, N. (1986).

Meta-analysis in clinical trials.

Control Clin Trials 7, 177–188.Dettori, J.R., Bullock, S.H., Sutlive, T.G., Franklin, R.J., Patience, T. (1995).

The effects of spinal flexion and extension exercises and their associated postures in patients with acute low back pain.

Spine 20, 2303–2312.Dworkin, R.H., Turk, D.C., Farrar, J.T., Haythornthwaite, J.A., Jensen, M.P.., et. al . (2005).

Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations.

Pain 113, 9–19.Dworkin, R.H., Turk, D.C., McDermott, M.P., Peirce-Sandner, S., Burke, L.B., Cowan, P. (2009).

Interpreting the clinical importance of group differences in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations.

Pain 146, 238–244.Epping-Jordan, J.E.,Wahlgren, D.R.,Williams, R.A., Pruitt, S.D., Slater, M.A., Patterson, T.L. (1998).

Transition to chronic pain in men with low back pain: Predictive relationships among pain intensity, disability, and depressive symptoms.

Health Psychol 17, 421–427.Faas, A., Chavannes, A.W., van Eijk, J.T., Gubbels, J.W. (1993).

A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of exercise therapy in patients with acute low back pain.

Spine 18, 1388–1395.Gracely, R.H., Kwilosz, D.M. (1988).

The Descriptor Differential Scale: Applying psychophysical principles to clinical pain assessment.

Pain 35, 279–288.Grotle, M., Brox, J.I., Glomsrod, B., Lonn, J.H., Vollestad, N.K. (2007).

Prognostic factors in first-time care seekers due to acute low back pain.

Eur J Pain 11, 290–298.Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM et al.

Prognosis in Patients with Recent Onset Low Back Pain in Australian Primary Care:

Inception Cohort Study

British Medical Journal 2008 (Jul 7); 337: a171Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Manniche C.

Low Back Pain: What Is The Long-term Course?

A Review of Studies of General Patient Populations

European Spine Journal 2003 (Apr); 12 (2): 149–165Higgins, J.P., Thompson, S.G., Deeks, J.J., Altman, D.G. (2003).

Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses.

BMJ 327, 557–560.Karjalainen, K., Malmivaara, A., Mutanen, P., Pohjolainen, T., Roine, R., Hurri, H. (2003).

Outcome determinants of subacute low back pain.

Spine 28, 2634–2640.Klenerman, L., Slade, P.D., Stanley, I.M., Pennie, B., Reilly, J.P., Atchison, L.E., Troup, J.D., Rose, M.J. (1995).

The prediction of chronicity in patients with an acute attack of low back pain in a general practice setting.

Spine 20, 478–484.Leboeuf-Yde, C., Lauritsen, J.M. (1995).

The prevalence of low back pain in the literature. A structured review of 26 Nordic studies from 1954 to 1993.

Spine 20, 2112–2118.McGuirk, B., King, W., Govind, J., Lowry, J., Bogduk, N. (2001).

Safety, efficacy, and cost effectiveness of evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute low back pain in primary care.

Spine 2001; 26: 2615?2622Price, D.D., McGrath, P.A., Rafii, A., Buckingham, B. (1983).

The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain.

Pain 17, 45–56.Roelofs, P.D., Deyo, R.A., Koes, B.W., Scholten, R.J., van Tulder, M.W. (2008).

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain: An updated Cochrane review.

Spine 33, 1766–1774.Schiottz-Christensen, B., Nielsen, G.L., Hansen, V.K., Schodt, T., Sorensen, H.T., Olesen, F. (1999).

Long-term prognosis of acute low back pain in patients seen in general practice: A 1-year prospective follow-up study.

Fam Pract. 1999; 16: 223–232Sieben, J.M., Vlaeyen, J.W., Portegijs, P.J., Verbunt, J.A., van Riet-Rutgers, S., Kester, A.D., Von Korff, M. (2005).

A longitudinal study on the predictive validity of the fear-avoidance model in low back pain.

Pain 117, 162–170.Spitzer, W.O. (1987).

Scientific approach to the assessment and management of activity-related spinal disorders.

A monograph for clinicians. Report of the Quebec Task Force on Spinal Disorders.

Spine 12, S1–59.van Middelkoop, M., Rubinstein, S.M., Kuijpers, T., Verhagen, A.P., Ostelo, R., Koes, B.W. (2011).

A Systematic Review on the Effectiveness of Physical and Rehabilitation Interventions

for Chronic Non-specific Low Back Pain

European Spine Journal 2011 (Jan); 20 (1): 19–39van Tulder, M., Koes, B.W., Bouter, L.M. (1995).

A cost-of-illness study of back pain in The Netherlands.

Pain 62, 233–240.van Tulder M, Becker A, Bekkering T, Breen A, Carter T, Gil del Real MT.

European Guidelines for the Management of Acute Nonspecific Low Back Pain in Primary Care

European Spine Journal 2006 (Mar); 15 Suppl 2: S169–191Von Korff, M., Ormel, J., Keefe, F.J., Dworkin, S.F. (1992).

Grading the severity of chronic pain.

Pain 50, 133–149.Wahlgren, D.R., Atkinson, J.H., Epping-Jordan, J.E., Williams, R.A., Pruitt, S.D., Klapow, J.C. (1997).

One-year follow-up of first onset low back pain.

Pain 73, 213–221.Weber, H., Holme, I., Amlie, E. (1993).

The natural course of acute sciatica with nerve root symptoms in a double-blind placebo-controlled trial evaluating the effect of piroxicam.

Spine 18, 1433–1438.Werneke, M., Hart, D.L. (2001).

Centralization phenomenon as a prognostic factor for chronic low back pain and disability.

Spine 26, 758–764; discussion 765.

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Since 8-30-2016

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |