Non-Invasive and Minimally Invasive

Management of Low Back DisordersThis section was compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2020 (Mar); 62 (3): e111–e138 ~ FULL TEXT

Hegmann, Kurt T. MD, MPH; Travis, Russell MD; Andersson, Gunnar B.J. MD, PhD; Belcourt, Roger M. MD, MPH; Carragee, Eugene J. MD; Donelson, Ronald MD, MS; Eskay-Auerbach, Marjorie MD, JD; Galper, Jill PT, MEd; Goertz, Michael MD, MPH; Haldeman, Scott MD, DC, PhD; et al.

American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine,

Elk Grove Village, Illinois.

OBJECTIVE: This abbreviated version of the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine's (ACOEM) Low Back Disorders Guideline reviews the evidence and recommendations developed for non-invasive and minimally invasive management of low back disorders.

METHODS: Systematic literature reviews were accomplished with article abstraction, critiquing, grading, evidence table compilation, and guideline finalization by a multidisciplinary expert panel and extensive peer-review to develop evidence-based guidance. Consensus recommendations were formulated when evidence was lacking. A total of 70 high-quality and 564 moderate-quality trials were identified for non-invasive low back disorders. Detailed algorithms were developed.

RESULTS: Guidance has been developed for the management of acute, subacute, and chronic low back disorders and rehabilitation. This includes 121 specific recommendations.

CONCLUSION: Quality evidence should guide treatment for all phases of managing low back disorders.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

This is the second of three articles that summarize recommendations for low back disorders from the ACOEM’s Low Back Disorders Guideline. This article focuses on the non-invasive treatment sections from the 862-page ACOEM Low Back Disorders Guideline (2,456 references). The first article [1] addresses assessment and diagnostic evaluation, while the third article will address invasive treatments.

The ACOEM’s Low Back Disorders Guideline is designed to provide health care providers with evidence-based guidance for management of low back disorders among working-age adults. Guidance in this article has been developed for acute (up to 1- month duration), subacute (1 to 3 months’ duration), and chronic (more than 3 months’ duration) clinical timeframes. This guideline does not address several broad categories including congenital disorders or malignancies. It also does not address specific intra-operative procedures. This article addresses the following multi-part questions by treatment phase (acute, subacute, chronic, postoperative) by the Evidence-based Practice Spine Panel:

What evidence supports the treatment of low back disorders with medications?

What evidence supports the treatment of low back disorders with complementary/alternative treatments?

What evidence supports the treatment of low back disorders with exercise?

What evidence supports the treatment of low back disorders with manipulation?

What evidence supports the treatment of low back disorders with massage?

What evidence supports the treatment of low back disorders with electrical therapies?

What evidence supports the treatment of low back disorders with heat or cold therapies?

Evidence for, and guidance development, was sought for the treatment of several spine disorders including low back pain (LBP), sciatica/radiculopathy, spondylolisthesis, facet arthrosis, degenerative disc disease, failed back surgery syndrome, and spinal stenosis.

The search strategies used seven databases (PubMed, Scopus, Medline, Cochrane, Google Scholar, Ebsco, CINAHL). A total of 1,134,216 articles were screened, of which 1,093 articles' abstracts were reviewed and evaluated against specified inclusion and exclusion criteria. A total of 775 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 42 systematic reviews were included in these guidelines that addressed non-invasive treatment of low back disorders. Evidence-based recommendations were developed and graded from (A) to (C) in favor and against the specific diagnostic test, with (A) level recommendations having the highest quality literature. Expert consensus was employed for insufficient evidence (I) to develop consensus guidance. This guideline achieved 100% Panel agreement for all of the developed guidance in this article with the sole exception of systemic glucocorticosteroids for radicular pain (see below).

Guidance was developed with sufficient detail to facilitate assessment of compliance (Institute of Medicine [IOM]) and auditing/monitoring (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation [AGREE]). [2, 3] Alternative options to manage conditions are provided when comparative trials are available. [4-12] All AGREE, [13] IOM, [14] AMSTAR, [15] and GRADE3 criteria were adhered to. [16] In accordance with the IOM’s Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines, this guideline underwent external peer review, and detailed records of the peer review processes are kept, including responses to external peer reviewers. [3]

The Evidence-based Practice Spine Panel and the Research Team have complete editorial independence from ACOEM and Reed Group, which have not influenced the guideline. The literature is continuously monitored and formally appraised for evidence that would materially affect this guidance. This guideline is planned to be comprehensively updated at least every 5 years or more frequently should evidence require it. All treatment recommendations are guidance based on synthesis of the evidence plus expert consensus. These are recommendations for practitioners, and decisions to adopt a particular course of action must be made by trained practitioners on the basis of available resources and the particular circumstances presented by the individual patient.

GENERAL TREATMENT PRINCIPLES

General treatment principles are addressed in a separate guideline, Initial Approaches to Treatment. [17] A succinct summary of a few of those principles are warranted prior to discussing individual treatment recommendations, as they impact the management of low back disorders.

Table 1 Patients should be provided a medication with evidence of efficacy. Limited numbers of medications should be prescribed. The effects of a medication should be recorded, with a particular focus on documenting objective and/or functional improvements (Table 1). [17] Ineffective medication(s) should be discontinued prior to provision of alternate medication(s). Multiple medications should not be simultaneously provided at the same visit except with some acute severe patients and occasionally when there is a change of provider with a need to institute efficacious medications from a non-evidencebased regimen. Patients should be provided a physical method that has quality evidence of efficacy. The effects of treatment should be documented, with attention to objective and/or functional improvements. Ineffective treatment(s) should be discontinued prior to provision of alternate treatment(s). Multiple treatments should generally not be simultaneously provided at the same visit except, for example, occasionally when there is a change of provider with a need to institute efficacious treatments from a non-evidence-based regimen.

NON-INVASIVE CLINICAL TREATMENT RECOMMENDATIONS OVERVIEW

Activity levels, aerobic exercise, and directional preference exercises (stretching in the direction that centralizes or abolishes the pain, see below) should be addressed

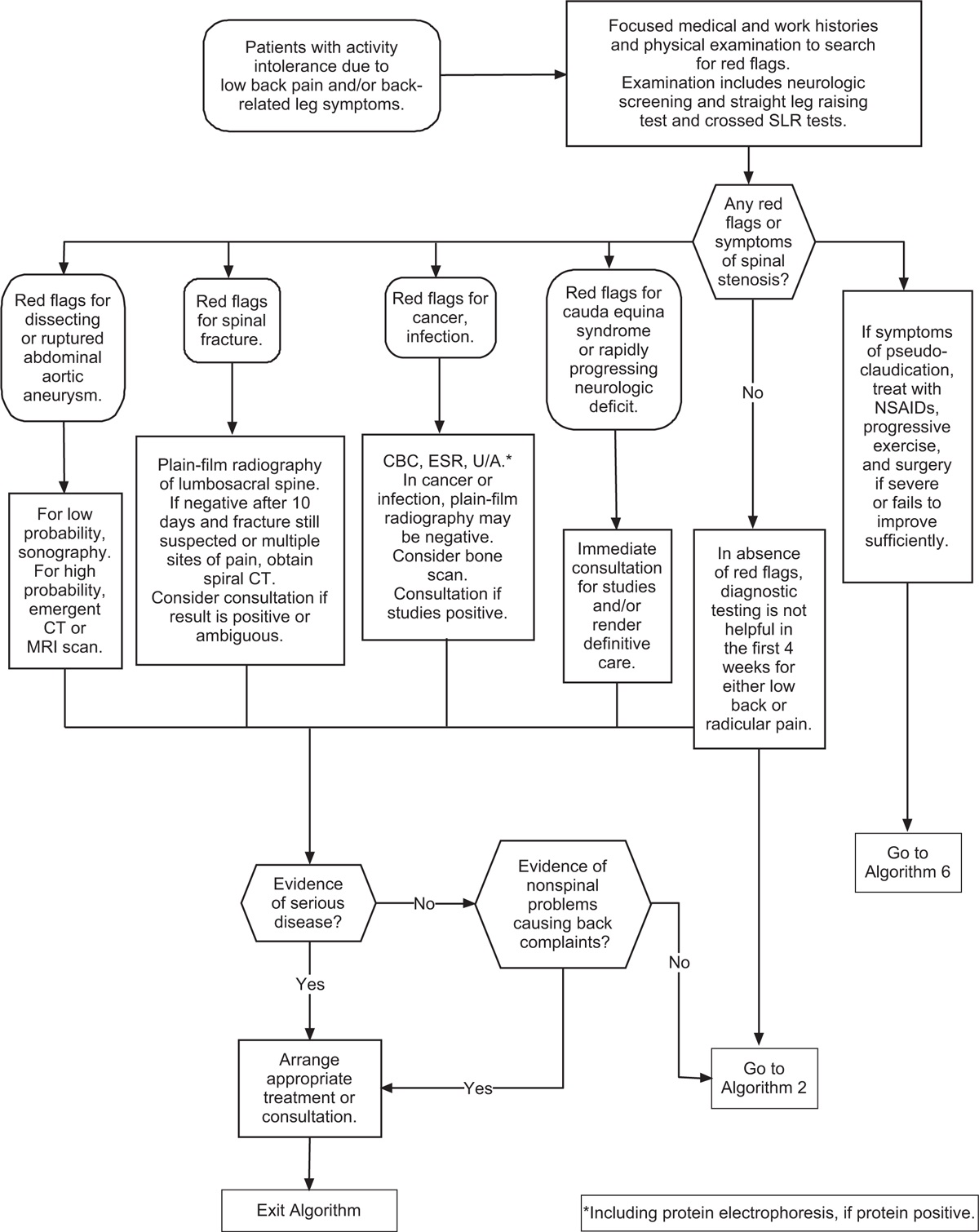

(see Algorithms – Figures 1, http://links.lww.com/JOM/A702, 2,

http://links.lww.com/JOM/A703, 3,

http://links.lww.com/JOM/A704).

Nonprescription analgesics may provide sufficient pain relief for most patients with acute and subacute LBP. If the treatment response is inadequate (ie, if symptoms and activity limitations continue) or the provider judges the condition limitations to be more significant, prescribed pharmaceuticals and/or physical methods can be added. Comorbid conditions, invasiveness, adverse effects, cost, and provider and patient preferences help guide the provider’s choice of recommendations. Initial care may include exercises, advice on activities, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, heat, cryotherapy, and manipulation. Education about LBP should begin at the first visit, including principles of fear avoidance belief training (FABT) for those with fear avoidance beliefs. Throughout the treatment phases, any given treatment should be assessed for efficacy and ineffective treatments should be discontinued rather than accumulated.

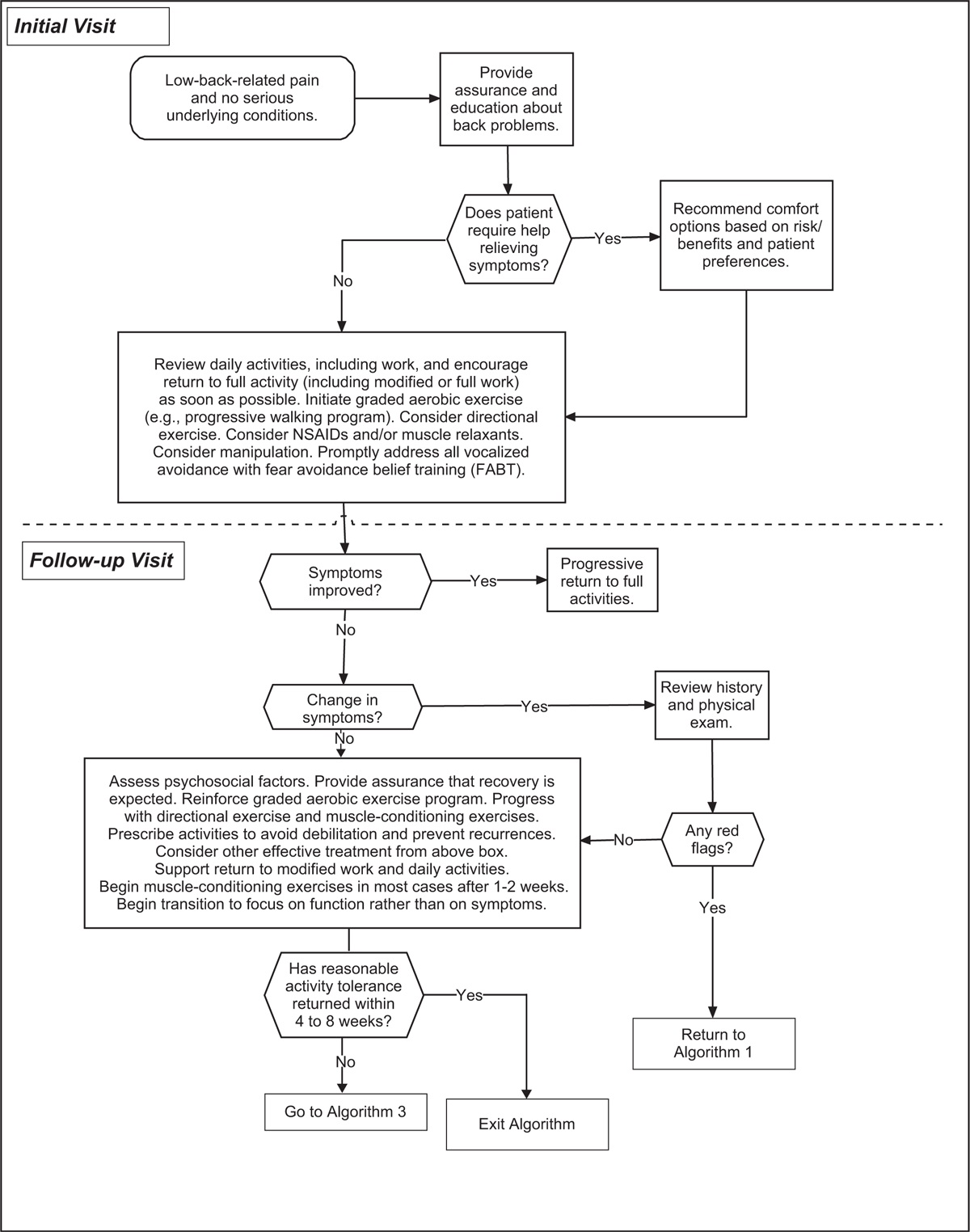

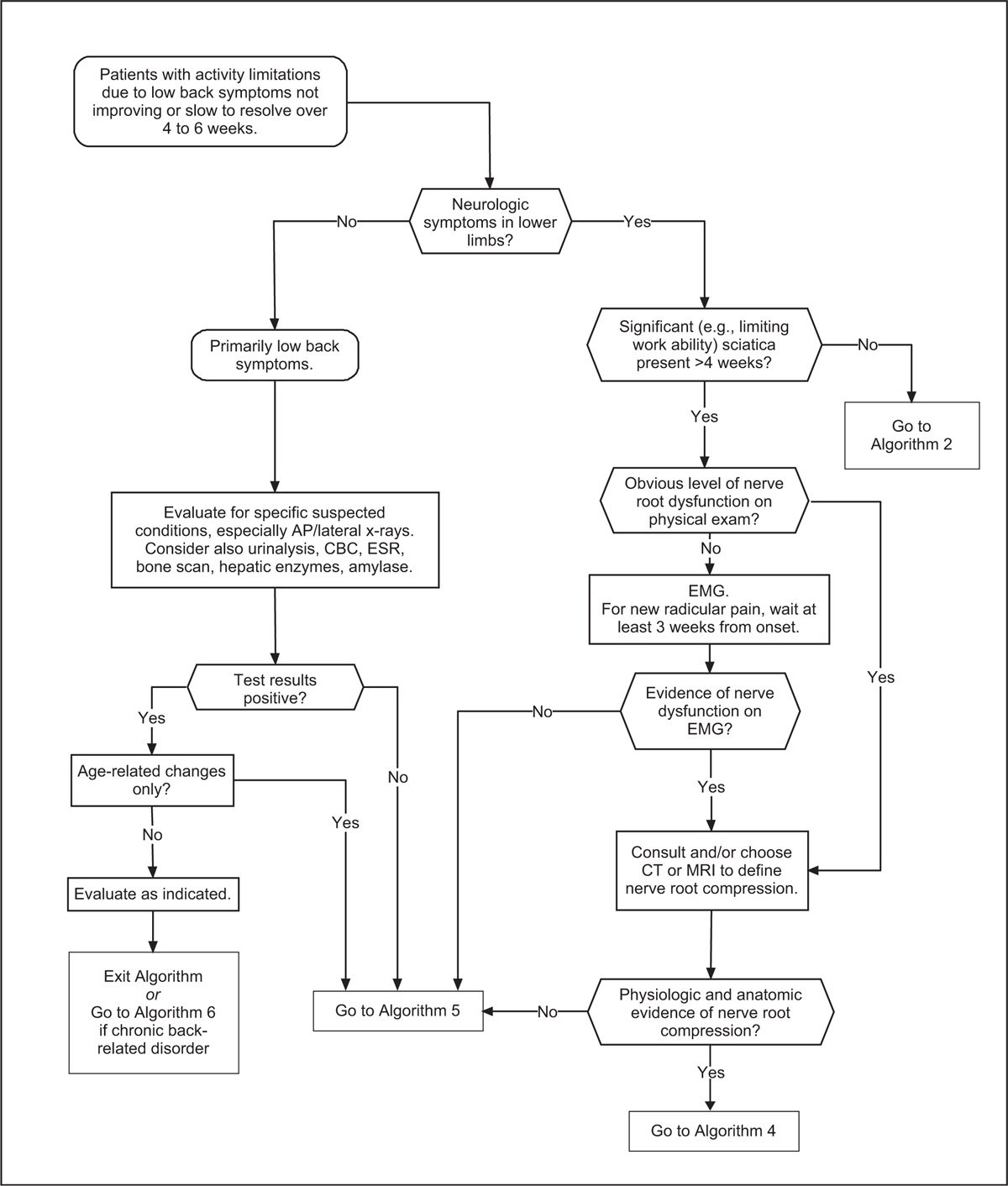

It is increasingly believed that chronically impaired LBP patients begin a course towards disability at, or before, their first clinical encounter. As such, those who do not respond to appropriate treatment should have their treatment, compliance, and psychosocial factors assessed early (see Algorithms – Figures 1, http://links.lww.com/ JOM/A702, 2, http://links.lww.com/JOM/ A703, 3, http://links.lww.com/JOM/A704). Additionally, those patients whose course ventures beyond the abilities of the provider should be referred to others with greater experience in evaluation and functional recovery of complex LBP patients.

The remainder of this document discusses evidence of efficacy for many LBP interventions used for spinal conditions. This evidence and consequent guidance are further subdivided, when possible, into acute, subacute, and chronic LBP, radicular pain syndromes, postoperative, and when evidence is available, other spinal conditions including spondylolisthesis, spinal stenosis, facet joint osteoarthrosis, and failed back surgery syndrome. A rigorous attempt has been made to ascertain evidence for radicular versus non-radicular pain in the development. However, the literature largely lacks specification of clear inclusionary and exclusionary criteria. Most trials did not report lower extremity symptoms and those that did nearly always reported percentages of subjects with ”leg pain” without clarifying whether this was general lower extremity pain or anatomically consistent nerve root pain. A minority of such studies reported stratified analyses to detect if such patients responded differently. However, where identifiable radicular pain patients were included, these have been noted.

ACTIVITIES AND ACTIVITY MODIFICATION

There has been a major revision in the management of activity limitations in patients with LBP over the past 10 to 20 years. Previously, bed rest was prescribed. It is now widely recognized that prescriptions of bed rest are ineffective (see following discussion), reinforce a belief that the injury is severe and likely contribute to debility and delayed recovery. Recommendations have been developed for posture, lumbar supports, and mattresses. The approach to exercise, or physical activity has been significantly revised. Revisions have also resulted from the greater understanding that the natural history of LBP is for there to be episodic recurrences and persistence, while “most workers do continue working or return to work while symptoms are still present: if nobody returned to work till they were 100% symptom free, only a minority would ever return to work.” [18–21]

In general, activities causing a significant increase in low back symptoms should be reviewed with the patient and modifications advised when appropriate. Heavy lifting, awkward postures, prolonged duration of a single posture, workstation design, and other activities may require at least temporary modification. Usually these activities are obvious to the patient, yet, this is not always true. For example, patients may not realize the importance of monitoring symptoms and adjusting their positions or activities prior to experiencing excessive back stiffness. It is important to emphasize that a modest increase in pain does not represent or document damage. Instead, such symptoms may actually be beneficial to the patient to experience some short-term pain. For example, arising from bed is usually painful for a patient with acute LBP. Yet, it is beneficial to the patient’s overall recovery to arise and maintain as nearly normal a functional status as possible (see Bed Rest, Exercise, and Fear Avoidance Belief Training). While the patient is recovering, activities that do not aggravate symptoms should be maintained and exercises should be advised to prevent debilitation due to inactivity. Evidence suggests aerobic exercise is a beneficial cornerstone therapeutic management technique for acute, subacute, and chronic LBP (see Aerobic Exercise). The patient should be informed that such activities might temporarily increase symptoms.

WORK ACTIVITIES

There are no quality studies identified to address this topic of work activity and limitations. Work activity modifications are often necessary. A patient’s return-to-work expectations are typically set prior to the first appointment, [22] thus education may be necessary to (re)set realistic expectations and goals. Advice includes how to avoid aggravating activities that result in more than a minor, temporary increase in pain. A review of work duties assists in decisions regarding whether or not modifications may be accomplished with or without employer notification and to determine whether modified duty is appropriate. Maintaining maximal levels of activity, including work activities, is recommended as not returning to work has detrimental effects on pain ratings and functionality. [23]

Work modifications should be tailored taking into consideration three main factors:(1) job physical requirements;

(2) severity of the problem; and

(3) the patient’s understanding of his or her condition.A fourth factor, employer expectations, does not influence the writing of limitations, but does influence whether the limitations will be accepted and/or enacted. Sometimes it is necessary to write limitations or prescribe activity levels that are above what the patient feels he or she can do, particularly when the patient feels that bed rest or similar non-activity is advisable. In such cases, overly restricting the patient should be avoided as it is clearly not in the patient’s best interest. Education about LBP and the need to remain active should concomitantly be provided.

Common limitations involve modifying the weight of objects lifted, frequency of lifts, and posture all while considering the patient’s capabilities. For cases of acute, severe LBP with or without radicular symptoms, frequent initial limitations for occupational and non-occupational activities include:

No lifting over 10 pounds,

No prolonged or repeated bending (flexion), and

Alternate sitting and standing as needed.

Activity guidelines are generally reassessed every week in the acute phase with gradual increases in activity recommended. The patient’s activity level should be kept at maximal levels and gradually advanced. Work activity limitations should be written whether the employer is perceived to have modified duty available or not. Written activity limitations guidance communicates the patient’s status and also provides the patient information on activity expectations and limitations at home.

BED REST

There are 11 moderate-quality RCTs incorporated into this analysis. [24–31] Bed rest was long used for the treatment of LBP, [24–30, 32–36] particularly acute LBP. Bed rest likely evolved from beliefs that LBP represented anatomical injury that necessitated activity limitations to improve recovery, without consideration of whether there might be any adverse short- or longterm implications. Evidence supports that bed rest is not recommended for the management of acute, subacute, chronic, radicular LBP, or stable spinal fractures all with High Confidence: Strongly Not Recommended (A) (Acute); Moderately Not Recommended (B) (Subacute, Chronic); Not Recommended (C) (Radicular); Not Recommended (I) (Stable Spinal Fractures). Bed rest is recommended for unstable spinal fractures Recommended (I), also with High Confidence. Bed rest is not recommended for other low back problems. Not Recommended (I), Moderate Confidence.Specific beds or other commercial sleep products are not recommended for prevention or treatment of acute, subacute, or chronic LBP, Not Recommended (I), Moderate Confidence.

FEAR AVOIDANCE BELIEF TRAINING (KINESIOPHOBIA)

There are no quality studies incorporated into this analysis. The Fear Avoidance Belief Model (aka, kinesiophobia) was developed to attempt to explain differences between patients who had resolution of acute LBP versus those who progressed to chronic LBP. [37–39] Fear Avoidance Belief Training (FABT) was developed to help individuals overcome fears that result in avoidance of activities and become selffulfilling and self-reinforcing. FABT has been evaluated in acute, subacute, and chronic LBP patients. The single quality study of acute LBP that included FABT found those with elevated fear avoidance beliefs benefitted.40 The other studies also suggest that those with elevated fear avoidance beliefs benefited from the intervention40–43 with one exception; that exception was in Norway among individuals on disability pensions, thus applicability to the United States or to acute, subacute, or even chronic LBP settings is questionable. [44, 45] Those with elevated fear avoidance beliefs are particularly successfully treated with these interventions, while those without may not benefit.Thus, FABT is Recommended (I), Moderate Confidence for acute, subacute, or chronic LBP patients with elevated fear avoidance beliefs at baseline with or without referred pain.

SITTING POSTURE

There are strong beliefs and little supportive quality evidence that achieving and/or maintaining lordotic postures are superior for LBP treatment and prevention. Lordotic sitting posture is recommended for treatment of acute, subacute, or chronic LBP, radicular pain and postoperative pain, Recommended (I), Low Confidence. A pillow or an existing feature of a motor vehicle seat is not invasive, has few adverse effects, is low cost and is recommended. There are no quality data supporting specific commercial products.

SLEEP POSTURE

There are no quality studies reported on sleep posture to prevent or treat LBP. Certain sleep postures have been sometimes thought of as superior. The controversy appears largely driven by a posturebased theory that a ”straight or neutral” spine while sleeping is beneficial. As supportive quality evidence is lacking, and absence of sleep is detrimental, sleep posture(s) that are most comfortable for the patient are instead recommended (Recommended (I), Low Confidence).

MATTRESSES, WATER BEDS, AND OTHER SLEEPING SURFACES

There are one high-quality46 and one moderate-quality [47] studies incorporated into this analysis. There are no quality studies on waterbeds or sleeping on the floor. Sleep disturbance is common with LBP. [48] Dogma holds that a firm mattress is superior for LBP treatment and/or prevention. [49] Commercial advertisements also advocate brand-name mattresses to treat LBP, [50] however, there are no quality data supporting specific commercial products. One moderate-quality study of chronic LBP patients reported a medium firm mattress was superior to a firm mattress,46 but it neither discussed sleep position nor prior mattress firmness which may be important issues. Thus, while the most comfortable sleeping surface and posture may be preferable, there is No Recommendation (I), Low Confidence (I) for or against specific mattresses, bedding, and water beds.

EXERCISES

Most articles regarding exercise have mixed various forms of exercise, thus this summary evidence review analyzed evidence of specific exercises when available. There are 18 moderate-quality studies incorporated into the analysis of aerobic exercise. [43, 51–67] There are two high-quality [68, 69] and 107 moderate-quality RCTs (one with multiple reports) incorporated into the analyses of directional preference, slump stretching, and strengthening exercise. [27, 43, 54, 60, 63, 66, 70–170]

Exercises have been considered among the most important therapeutic options for the treatment and rehabilitation of LBP. [77, 96, 129, 131, 137, 160, 171–210] While there are many ways to categorize and analyze exercise, this guideline evaluates exercise in four broad groupings: (1) aerobic exercise; (2) directional exercises; (3) stretching; and (4) strengthening. Additional subsequent sections include reviews of aquatic therapy, yoga, tai chi, and Pilates. An exercise prescription is Moderately Recommended (B), High Confidence for acute, subacute, chronic, postoperative, and radicular LBP patients. This may be self-administered or enacted through formal therapy appointments.

Aerobic exercises, most commonly a progressive walking program targeting either time or distance, are recommended for all patients from the initial appointment as follows: Moderately Recommended (B) for acute and subacute LBP, Strongly Recommended (A) for chronic LBP, Recommended (C) for radicular pain, Recommended (I) for postoperative patients [109, 166, 211–213] all with High Confidence. Regarding quantification, one successful program for chronic LBP targeted progressive walking at least 45 minutes, four times a week at 60% of predicted maximum heart rate (220 – age ¼ predicted predicted maximum heart rate). [52]

Directional exercises which centralize or abolish the pain are Recommended (C) for acute LBP, Recommended (I) for subacute, chronic, and radicular LBP [77, 137, 214–218] all with Moderate Confidence. These exercises are appropriate when a beneficial pattern of pain response (directional preference, pain centralization, or elimination) is identified during patient testing with standardized directions of endrange spinal movements. When appropriate, the exercises are initially performed every 2 hours (8 to 10 repetitions) to fully centralize and abolish the pain along with posture modifications that also honor the patient’s directional preference. The same exercise typically also serves to protect the patient from symptoms returning during and after recovery. Slump stretching exercises three to five times a day are an option and are Recommended (C) for acute LBP, and Recommended (I) for subacute, and chronic LBP, [77] all with Low Confidence. Stretching exercises as an isolated LBP prevention program are Not Recommended (C), Low Confidence, and there is a lack of evidence that generic, non-specific stretching exercises are of assistance in treating patients with acute LBP. [121, 134] Stretching exercises for treatment of chronic LBP in the absence of significant range of motion deficits may result in lack of adherence to functional goals including aerobic and strengthening exercises and thus, are Not Recommended (I), Low Confidence.

Strengthening exercises are Recommended (C), High Confidence for nearly all LBP patients other than those with acute LBP that resolves rapidly or acute LBP in the early acute treatment phase when strengthening could aggravate the pain. [70, 75, 76, 93, 110, 114, 155, 219–222]

Specific strengthening exercises, such as stabilization exercises, are also helpful for the prevention and treatment (including postoperative treatment) of LBP and thus are Recommended (C), High Confidence. [89, 93, 114, 221]

Abdominal strengthening exercises as a sole or central goal of a strengthening program for treatment or prevention of LBP are Not Recommended (I), Low Confidence. [223]

AQUATIC EXERCISE

There are seven moderate-quality RCTs incorporated into this analysis.51 Aquatic therapy has indications to make it a select recommendation (eg, extreme obesity, significant degenerative joint disease, etc), as a progressive walking program is generally preferable for longer term exercise program maintenance in the vast majority of patients. Yet, those select indications are where aquatic therapy may be successful.

Aquatic therapy is Recommended, Evidence (C) for select chronic LBP and Recommended (I), Moderate Confidence for subacute LBP patients. [60, 224–228]

Aquatic therapy is Not Recommended (I), Moderate Confidence for all other subacute and chronic LBP patients. [225]

LUMBAR EXTENSION

There is one moderate-quality RCT incorporated into this analysis. [111] Lumbar extension machines are intended to address LBP through the development of muscle strength in specific muscle groups through specific exercises, [111, 229–231] yet in the absence of quality evidence of efficacy, they are Not Recommended (I), Low Confidence.

YOGA AND TAI CHI

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4 There are two high-quality [68, 232] and nine moderate-quality [112, 233–240] studies incorporated into this analysis. Yoga for treatment of LBP has not been standardized, but tends to involve postures, stretches, breath control, and relaxation. Traditional yoga is different and involves rules for personal conduct, postures, breath control, sense withdrawal, concentration, meditation, and self-realization, [239, 241] and different versions are practiced (eg, Ashtanga, Iyengar, Hatha).

Exercise aspects of yoga and tai chi for select, motivated patients with chronic LBP are Recommended (C), [68, 232, 233, 235–237, 238, 240, 242, 243] and for acute and subacute LBP patients, there is No Recommendation (I), all with Low Confidence. [204, 244–246]

There is No Recommendation (I), Low Confidence for treatment of LBP with pilates as quality evidence is lacking (Figures 1–3). [112, 234]

NON-STEROIDAL ANTIINFLAMMATORY MEDICATIONS

There are 12 high-quality [247–258] and 37 moderate-quality studies (one with two reports) [98, 259–295] incorporated into this analysis. NSAIDs have been widely used for treatment of painful back conditions, including acute LBP, subacute LBP, chronic LBP, radicular, and postoperative patients and other back disorders [296–304] and have consistent evidence of superiority to placebo, such that NSAIDs are Strongly Recommended (A), High Confidence for acute, chronic, and radicular syndromes and Moderately Recommended (B), High Confidence for subacute and postoperative pain. [248, 249, 252–254, 259, 267, 270, 280]

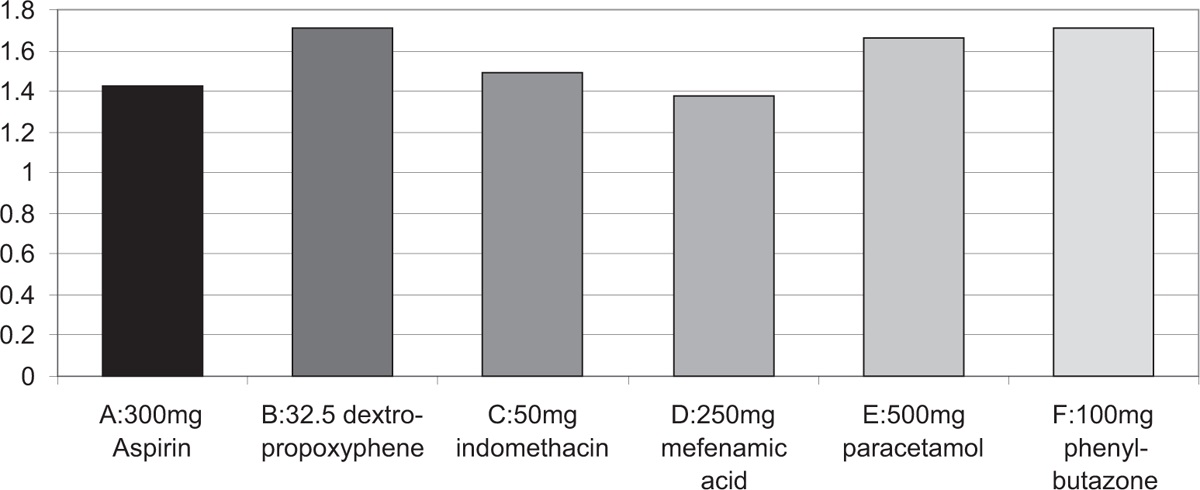

In most acute LBP patients, scheduled NSAID dosage rather than as needed (”PRN”) is generally preferable. As needed prescriptions and over-the-counter dosing may be reasonable for mild and some moderate LBP. If there is consideration for needing another medication, then scheduled NSAID dosing should generally be prescribed. The results of the RCT with the largest numbers of comparison groups for treatment of acute LBP are graphed in Figure 4 and indicate the best pain relief was in the NSAID groups, which outperformed paracetamol and an opioid (dextro-propoxyphene). Acetaminophen is an acceptable alternative with some evidence of efficacy, but is inferior to NSAIDs and thus is Recommended (C), High Confidence. [280, 281, 303, 305]

Although gastrointestinal bleeding is rarely problematic in employed populations, when there is increased risk and as NSAIDs are superior, concomitant prescription of proton pump inhibitors are Strongly Recommended (A), sucralfate is Moderately Recommended (B), and H2 blockers are Recommended (C), all with High Confidence. [306–310]

Aspirin or acetaminophen are Recommended (I), High Confidence for those with known cardiovascular disease or multiple cardiovascular risks and the degree of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibition is believed to be related to cardiovascular risk among the NSAIDs. [306, 311–318]

ANTIBIOTICS

There is one high-quality [319] and one moderate-quality study [320] incorporated into this analysis. Antibiotics (amoxicillin/clavulanate 500 mg/125 mg TID for 100 days) have been used of highly selective treatment of LBP that includes Modic changes and bone edema. [319, 321] Evidence conflicts. Accordingly, there is No Recommendation (I), Low Confidence for use in LBP patients other than proven infection.

ANTI-DEPRESSANTS

There are four high-quality [322–325] and 14 moderate-quality [326–339] studies or crossover trials incorporated into this analysis. Anti-depressants have been widely utilized for the treatment of chronic LBP, and evidence suggests submaximal doses are generally effective. Norepinephrine blocking appears required for efficacy, and thus selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, bupropion, and trazodone are ineffective and Strongly Not Recommended (A), Moderate Confidence for chronic LBP and Not Recommended (I) for other LBP syndromes. [322, 324, 328, 332]

Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor antidepressants (eg, tricyclic anti-depressants—amitriptyline, imipramine, nortriptyline, desipramine, maprotiline, doxepin) and mixed serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (eg, duloxetine) are Strongly Recommended (A) for chronic LBP and Recommended (C) for acute and subacute pain, both with Moderate Confidence. [322, 323, 326, 330, 331, 335–337, 339]

There is No Recommendation (I), Low Confidence for treatment of postoperative and radicular LBP. [323, 326, 334, 335]

ANTI-CONVULSANTS

There are seven high-quality [340–346] and nine moderate-quality studies incorporated into this analysis. [286, 347–354]

Anti-convulsant agents have been utilized off-label particularly for chronic radicular and neuropathic pain. [355–360] Gabapentin is an anti-convulsant also approved for the treatment of neuropathic pain.

Anti-convulsants including gabapentin have evidence showing a lack of efficacy and thus they are Not Recommended (C), Low Confidence for acute, subacute, and chronic LBP. [340, 345, 352–354, 361–363]

Anticonvulsants, including gabapentin and pregabalin, are not recommended for chronic radicular pain syndromes. [345, 346, 353, 354]

Topiramate is Recommended (C), Low Confidence for chronic LBP patients with depression or anxiety, [340] although it is generally recommended after exercises and trials of NSAIDs and anti-depressants. Gabapentin or pregabalin for perioperative pain management to reduce the need for opioids, particularly in patients with adverse effects from opioids, are efficacious and are Strongly Recommended (A), High Confidence. [342, 343]

There is No Recommendation (I), Low Confidence for use of other anti-convulsants for perioperative management. Gabapentin is Recommended (C), Moderate Confidence for treatment of severe neurogenic claudication with limited walking distance. [350]

BISPHOSPHONATES, CALCITONIN, AND THIOCOLCHICOSIDE

There are no quality studies incorporated into these analyses. Bisphosphonates and calcitonin are Not Recommended (I), Moderate Confidence for chronic LBP management. However, they may have uses for osteoporosis management.

Oral and intravenous colchicine are Not Recommended (I), Moderate Confidence for treatment of acute, subacute, or chronic LBP. [364–366]

There is No Recommendation (I), Low Confidence for or against use of thiocolchicoside for treatment of acute, subacute, or chronic LBP. [367, 368]

LIDOCAINE PATCHES, NMDA RECEPTOR ANTAGONISTS

There is one high-quality [369] and one moderate-quality [370] study incorporated into this analysis. Lidocaine patches are increasingly used to treat numerous pain conditions ranging from LBP to carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) to postherpetic neuralgia. [369, 371]

However, a moderate quality trial suggests lack of efficacy [370] and thus lidocaine patches are Not Recommended (C), Moderate Confidence for treatment of chronic LBP and there is No Recommendation (I) for other spine conditions.

There are no quality studies incorporated into the analysis of N-methyl-Daspartate (NMDA) receptor/antagonists. These medications including dextromethorphan are Not Recommended (I), Moderate Confidence.

OPIOIDS

Opioids have been reviewed in the Opioids Guideline. [372, 373] Opioids are Strongly Not Recommended (A), High Confidence for treatment of non-severe pain. Opioids are Recommended (C), High Confidence for highly selective use to treat severe acute pain from severe injuries, and postoperative pain (see Opioids Guideline for numerous recommendations). [372, 373]

Adjunctive treatments should nearly always be used (eg, NSAIDs, exercises). Screening for increased risk of adverse effects should be performed. The maximum morphine equivalent dose should generally not exceed 50 mg per day, and only those with incremental functional gain beyond that achieved up to 50 mg per day may be candidates for increased doses up to 90 mg per day [374, 375] (see Opioids Guideline for additional recommendations). [372]

SKELETAL MUSCLE RELAXANTS

There are three high- [376–378] and 33 moderate-quality [289, 292, 379–409] RCTs or crossover trials incorporated into this analysis.

Skeletal muscle relaxants comprise a diverse set of pharmaceuticals designed to produce ”muscle relaxation” purportedly through different mechanisms of action— generally considered to be effects on the central nervous system (CNS) and not directly on skeletal muscle. [410, 411]

Therapeutic exercises and NSAIDs are considered first line agents, ahead of muscle relaxants. As sedative effects are reported in approximately 25% to 50% of patients, muscle relaxants should generally be used when not at work, and not prior to starting a work shift, operating a motor vehicle, machinery or performing safety-sensitive work. [412, 413]

Daytime use is acceptable in circumstances where there are minimal CNS-sedating effects and little concern about sedation compromising function or safety. Muscle relaxants (not including carisoprodol) are Moderately Recommended (B), Moderate Confidence as a second-line treatment in moderate to severe acute LBP that has not been adequately controlled by NSAIDs. [377, 379, 391, 403, 408, 414]

Muscle relaxants are Not Recommended (I), Moderate Confidence for treatment of acute mild to moderate LBP. They are selectively Recommended (I), Low Confidence for acute exacerbations of chronic LBP or postoperative muscle spasm, [378, 379, 389, 409] but otherwise are Not Recommended (I), Low Confidence for treatment of chronic LBP.

Carisoprodol and diazepam are Not Recommended (I), Low Confidence due to their abuse potential and lack of superiority to other muscle relaxants. [299, 382, 415-418]

GLUCOCORTICOSTEROIDS

There are three high-quality [419–421] and three moderate-quality [422–424] studies incorporated into this analysis. Glucocorticosteroids are used to treat symptomatic herniated discs both through local injections (eg, epidural glucocorticosteroid injections) and oral agents to attempt to reduce localized inflammation and swelling. [425–452]

The single blinded trial of a 15- day course of oral prednisone (5 days at 60 mg, then 5 days at 40 mg, then 5 days at 20 mg) for treatment of radicular pain that included long-term follow-up suggested long-lasting benefits compared with placebo suggesting apparent efficacy. [420]

Other studies also suggest modest efficacy, thus systemic glucocorticosteroids are Recommended (C), Moderate Confidence for treatment of acute and subacute radicular pain. However, Panel agreement was 56% compared with 44% who felt glucocorticosteroids should be not recommended in part due to the adverse effect profile. There is No Recommendation (I), Moderate Confidence for treatment of chronic radicular pain syndromes. Glucocorticosteroids have been found to be ineffective for management of LBP [419, 420, 422, 424] and thus they are Moderately Not Recommended (B) for acute LBP and Not Recommended (I) for subacute or chronic LBP, both with High Confidence.

TUMOR NECROSIS FACTOR ALPHA INHIBITORS

There are two high-quality [453, 454] and 2 moderate-quality studies [455, 456] incorporated into this analysis.

Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-a) is theorized to have a role in resorption of herniated intervertebral discs and also in producing the pain associated with herniated discs. Adalimumab and infliximab are monoclonal antibodies against TNF-a. Etanercept is a tumor necrosis factor receptor inhibitor. They have been used for a number of rheumatological conditions, as well as in uncontrolled trials of sciatica. [457–459]

Most RCTs failed to find beneficial effects of infliximab for lumbar radicular pain syndromes [454–456] in contrast with results from non-RCTs, and thus, TNF-a are Moderately Not Recommended (B), Moderate Confidence. TNF-a are also Not Recommended (I), Moderate Confidence for other spine conditions.

MEDICAL FOODS

There is one moderate-quality study incorporated into this analysis. [460] Theramine, an amino acid formulation (AAF), has been used as a prescription medical food to purportedly reduce pain and inflammatory processes through dietary management. [460] There are no placebo-controlled trials identified. There is one moderatequality trial comparing theramine with low dose naproxen. [460] This may have biases similar to a non-treatment or waitlisted control group. Thus, in the absence of quality trials, there is No Recommendation (I), Low Confidence for treatment of spine disorders.

HERBAL AND OTHER PREPARATIONS

There are two high-quality [461, 462] and four moderate-quality [463–466] studies incorporated into this analysis.

Herbal treatments have been utilized to treat LBP, including Camphora molmol, Salix alba, Melaleuca alternifolia, Angelica sinensis, Aloe vera, Thymus officinalis, Menthe piperita, Arnica montana, Curcuma longa, Tanacetum parthenium, Harpagophytum procumbens, and Zingiber officinale. Herbal treatments/supplements are not well regulated in the United States and research regarding therapeutic and biologically available dosage is limited. There is a potential for a placebo effect to be misinterpreted as a sign of efficacy. [461, 462, 467]

Evidence of efficacy varies across these compounds, but dosing is not well controlled and there is no quality evidence for efficacy of these. Therefore, there is No Recommendation (I) for all of these with the exception that willow bark (salix) [463, 464, 468] is Not Recommended (I), Low Confidence. If salicylates are used as treatment, generic aspirin is preferable to willow bark or salicin.

CAPSAICIN, OTHER CREAMS, OINTMENTS, AND TOPICAL AGENTS

There are two high-quality [469, 470] and three moderate-quality [464, 471, 472] studies incorporated into this analysis.

Capsaicin is applied to the skin as a cream or ointment and is thought to reduce pain by stimulating other nerve endings, thus it is thought to be potentially effective through distraction.

Rado-Salil ointment is a proprietary formulation of 14 agents, the two most common of which are menthol (55.1%) and methylsalicylate (26.5%). There are many other commercial products that similarly cause either a warm or cool feeling in the skin.

All of these agents are thought to work through a counter-irritant mechanism (ie, feeling the dermal sensation rather than the LBP). These compounds may also be used in those patients who prefer topical treatments over oral treatments and other more efficacious treatments but have only mild LBP.

There is some evidence that capsaicin compounds should not be used chronically due to reported adverse effects on neurons. [473]

Capsaicin appears superior to Spiroflor. While other treatments appear likely to have greater efficacy (eg, NSAIDs, progressive exercise program, etc), capsaicin may be a useful adjunct and is Moderately Recommended (B), Moderate Confidence for short-term but not long-term treatment of acute or subacute LBP or temporary flare-ups of chronic LBP. [464, 469–472]

Spiroflor is Not Recommended (I), Low Confidence for treatment of acute, subacute, or chronic LBP as it appears less efficacious than capsaicin and there are other treatments that are efficacious. The use of topical NSAIDs or other creams and ointments for treatment of acute, subacute, or chronic LBP have No Recommendation (I), Low Confidence. For treatment of chronic LBP, DMSO, N-acetylcysteine, EMLA, and wheatgrass cream are Not Recommended (I), Low Confidence

VITAMINS

There is one moderate-quality RCT incorporated into this analysis. [474]

Vitamins have been used to treat spine disorders, especially anti-oxidants, although all antioxidants are simultaneously pro-oxidants, [475, 476] thus evidence of potential harm from vitamins, particularly vitamin E, is accumulating. [477–479]

Vitamins, minerals, and supplements include glucosamine, bromelain, variations of B vitamins, vitamin C, zinc, and manganese. [480]

Studies have suggested a correlation between non-specific musculoskeletal pain and vitamin D deficiency, but no significant correlation has been demonstrated in patients with LBP and vitamin D deficiency. [481, 482] RCTs are needed for better understanding vitamin D repletion in patients with chronic LBP. [474, 483]

As there is an absence of quality evidence of efficacy of vitamins for treatment of spine disorders in the absence of documented deficiencies, vitamin supplementation is Not Recommended (I), Low Confidence.

KINESIOTAPING (INCLUDING KT TAPE AND ROCKTAPE) AND TAPING

There are no high quality and four moderate-quality studies incorporated into this analysis. [484–487] Taping and kinesiotaping (including KT tape and Rocktape) are used on the extremities and the spine particularly in sports settings. There are no consistent quality studies demonstrating kinesiotaping and taping are efficacious for the treatment of acute, subacute, or chronic LBP or radicular pain syndromes or other back-related problems.

While one moderate-quality study suggested it may be effective, three others found it ineffective, [484–487] and thus kinesiotaping is Not Recommended (C), Moderate Confidence for treatment of spine conditions.

SHOE INSOLES AND SHOE LIFTS

There are no high quality and three moderate-quality studies incorporated into this analysis. [488–490] There is one quality study reported comparing shoe insoles in patients with LBP, apparently mostly in chronic LBP patients. All of these studies, even those attempting blinding, suffer from probable unblinding of participants and placebo effects. [488–490]

Shoe lifts are Recommended (I), Low Confidence for treatment of chronic or recurrent LBP among individuals with significant leg length discrepancy of more than 2 cm, otherwise they are Not Recommended (I), Moderate Confidence for treatment of other spine disorders.

Shoe insoles or lifts are Not Recommended (C), Moderate Confidence for prevention of LBP. There is No Recommendation (I), Low Confidence for shoe insoles for those with prolonged walking requirements.

LUMBAR SUPPORTS

There are 10 moderate-quality RCTs incorporated into this analysis. [491–500] Lumbar supports range from soft wrap-around appliances to reinforced braces to rigid braces and have been used to treat various phases of lumbar pain [493, 494, 501–504] and post-surgical rehabilitation. They have also been used for prevention of LBP. [498, 505–508]

The rigid devices have been used particularly in postoperative lumbar fusion with a goal to facilitate boney union, and while there are no quality studies for that purpose, they are Recommended (I), High Confidence for that discrete indication.

Most of the highest quality studies suggest lack of efficacy of lumbar supports for either the prevention or treatment of LBP, and thus they are Not Recommended (C), Moderate Confidence. [491–500]

MAGNETS

Two moderate-quality RCTs suggest a lack of efficacy and none support efficacy, [509, 510] thus magnets are Moderately Not Recommended (B), High Confidence for treatment of any LBP disorder.

IONTOPHORESIS

There are no high- or moderate-quality studies incorporated into this analysis. Iontophoresis is a drug delivery system utilizing electrical current to transdermally deliver typically either glucocorticosteroids or NSAIDs and that has apparent efficacy in select disorders of the extremities where the dermis and adipose tissue overlying the target tissue is thin and penetration of the medicine to the target tissue is plausible.

As there are no quality studies showing iontophoresis is effective for any of the LBP disorders, there is No Recommendation (I), Low Confidence.

MASSAGE

There are no high-quality and 14 moderate-quality studies incorporated into this analysis. [110, 137, 273, 494, 511–519] Massage is a commonly used treatment for LBP. [299, 304, 520–527]

Massage is theorized to aid muscle and mental relaxation which could hypothetically result in increased pain tolerance through endorphin release. [528–530]

Relatively few higher quality trials of massage have been reported, varying massage methods have been used, methods and patient populations differed substantially between trials, and long-term follow-up is largely lacking [494, 531] resulting in heterogeneous results. Many trials have utilized massage as a control treatment for other interventions. [494]

Most trials suggest modest benefits. Massage is Recommended (C), Low Confidence for select use in subacute or chronic LBP as an adjunct to more efficacious treatments consisting primarily of a graded aerobic and strengthening exercise program. [110, 137, 273, 494, 511–519, 532]

Objective improvements should be shown approximately half way through the regimen to continue a treatment course. Massage is Recommended (I), Low Confidence for select use in acute LBP or chronic radicular pain syndromes in which LBP is a substantial symptom component. Mechanical devices for administering massage are Not Recommended (C), Moderate Confidence. [514, 515]

REFLEXOLOGY

There are no high-quality and two moderate-quality studies incorporated into this analysis. [533, 534]

Reflexology focuses on massage of reflex points which are believed to be linked to physiological responses and healing of other tissues including those in the back. [535]

Reflexology has not been shown to be clearly efficacious for the treatment of chronic LBP in either of two moderate-quality studies, [533, 534] and is thus Not Recommended (C) for chronic LBP and Not Recommended (I) for other LBP disorders, both with Moderate Confidence.

MYOFASCIAL RELEASE

There are no high-quality and one moderate-quality studies incorporated into this analysis. [536]

Myofascial release is a manual soft tissue technique to attempt to stretch and apply traction on target tissue(s). It is most commonly used in the periscapular area to treat non-specific upper thoracic muscle soreness. There are no placebo or sham-controlled trials for treatment of LBP. There is one comparative trial and it does not show clear efficacy, [536] thus there is No Recommendation (I), Low Confidence for treatment of any of the LBP disorders with myofascial release.

TRACTION

There is one high- (with two reports) [537, 538] and 19 moderate-quality [157, 174, 381, 492, 515, 539–552] studies incorporated into this analysis. Traction is the distraction of structures within the lumbar spine by application of tension along the axis of the spinal column that has been most frequently used to treat radicular syndromes. [179, 531, 541, 553–560]

Types of traction include motorized, manual, bed rest, pulley-weight, gravitational, suspension, and inverted, with manual and motorized being most commonly used. Trials with subgroups of patients have appeared promising for a minority of patients, but full validation studies are yet to be reported. [174, 556]

Nearly all of the highest quality studies for treatment of LBP patients failed to show meaningful benefits from traction. [174, 537, 538, 548–550] Its theoretical utility in radicular pain patients has also not been borne out as more studies show a lack of efficacy [537, 539, 546, 547] than show efficacy. [540, 544, 548]

Thus, traction is Strongly Not Recommended (A) for treatment of subacute or chronic LBP, Moderately Not Recommended (B) for radicular pain, and Not Recommended (I) for acute or postoperative LBP, all Moderate Confidence.

DECOMPRESSION AND DECOMPRESSIVE DEVICES

There are no high-quality and two moderate-quality studies incorporated into this analysis. [561, 562] Decompression through traction is a treatment that utilizes a therapeutic table and traction mechanism. Its intent is to reduce intradiscal pressure, thus allowing for disc decompression. There is no clear quality evidence for efficacy, [554, 561–563] analogy to other traction trials is not promising, thus decompression through traction and spinal decompressive devices is Not Recommended (I), Moderate Confidence for treatment of acute, subacute, chronic, postoperative LBP, or radicular pain syndromes.

INVERSION THERAPY

There is one moderate-quality RCT incorporated into this analysis. [564] Inversion therapy has been used for treatment of patients with herniated discs [564] and LBP, but as there is no quality evidence of efficacy, there is No Recommendation (I), Low Confidence.

MANIPULATION AND MOBILIZATION

There are one high-quality [252] and 36 moderate-quality RCTs incorporated into this analysis (five with multiple reports). [53, 95, 154, 155, 160, 211, 263, 273, 492, 493, 547, 565–594] Manipulation and mobilization include widely different techniques. [568, 571, 595–598]

In general, mobilization involves assisted, lowforce, low-velocity movement. Manipulation involves high-force, high-velocity, and lowamplitude action with a focus on moving a target joint. As commonly used, ”adjustment” isgenerallyasynonymformanipulation. There are numerous types of manipulation utilized in different studies. It seems unlikely that if there is an effect of manipulation, that it should be the same regardless of diagnosis, technique, or any other factors. This results in difficulties with comparing methods,techniques, or results across the available literature. These differences appear to be largely unstated in the available systematic reviews, which have aggregated all studies.

The highest quality sham-manipulation trial suggested no benefits of manipulation. [593] A clinical prediction rule (CPR) appeared quite promising, [53, 574] yet, was unable to be validated. [130, 135] Of the five highest quality studies of manipulation, three found no benefit, [252, 576, 599] one resulted in the CPR not being subsequently validated [53] and only one was positive for comparing manipulation with non-thrust manipulation. [565] However, most of the evidence continues to suggest manipulation is approximately as efficacious as common physiotherapy interventions such as stretching or strengthening exercises for treatment of acute and chronic LBP. There are many additional moderate-quality studies evaluating manipulation, although there are problems with quality of the available literature, [600–602] use of mixtures of manipulation with exercises and other treatments precluding conclusions on efficacy of spinal manipulation, and suboptimal statistical testing. [598, 603]

There are comparative trials with ”usual care” (which often is not modern quality evidence-based treatment and/or contain numerous uncontrolled cointerventions) but no quality studies demonstrating superiority of manipulation for LBP patients compared with the other evidence-based treatment strategies (eg, NSAIDs, progressive walking program, directional exercises, and heat) contained in this guideline. One comparative trial suggested adjunctive manual-thrust manipulation was modestly superior to mechanical-assisted manipulation (MAM) at 4 weeks but not longer-term. Both also treated with ibuprofen, with no differences between MAM and largely unstructured ”usual medical care.” [571] These weaknesses have resulted in a decrease in the prior strength of evidence rating for manipulation for acute pain to ”I” from ”B.”

Manipulation or mobilization of the lumbar spine is Recommended (I), Low Confidence for select treatment of acute or subacute LBP, or radicular pain syndromes without neurological deficit, generally if needed after treatment with NSAIDs, directional and aerobic exercise. Patient preference is an indication for early use of manipulation. Manipulation may also be considered for treatment of severe, acute LBP concurrently with directional exercises, aerobic exercise, and NSAIDs with the goal to improve motion and hopefully to decrease pain and enable more efficient exercise. Objective improvements should be shown approximately halfway through the regimen to continue a treatment course. There is no quality evidence that more than 12 visits are helpful for an episode of LBP, thus ongoing manipulation is not indicated.

Manipulation or mobilization for short-term relief of chronic pain while used as a component of an active exercise program is also Recommended (C), Low Confidence. While ”leg pain” was included in some studies, nearly all excluded patients with symptoms consistent with sciatica [589] and essentially all have eliminated those with neurological deficits. Manipulation is Not Recommended (I), Low Confidence for treatment of radicular pain syndromes with progressive motor loss. Manipulation or mobilization of regions outside of/not adjacent to the lumbopelvic area (eg, cervical spine, lower extremity) when treating LBP is Not Recommended (I), High Confidence.

MANIPULATION UNDER ANESTHESIA (MUA) AND MEDICATION-ASSISTED SPINAL MANIPULATION (MASM)

There is one moderate-quality RCT incorporated into this analysis. [604]

Manipulation under anesthesia (MUA) and medication-assisted spinal manipulation (MASM) involves the administration of anesthesia or medication followed by manipulation of the spine with the intended effect of relieving LBP. [605–610]

MUA and MASM have been evaluated in chronic LBP patients in one RCT; however, that study used a complex mixture of interventions and changed multiple interventions between the two groups. [604]

Thus, there is no quality study reported comparing these with either a non-interventional control or other evidence-based treatment. There are also no quality studies that solely evaluate MUA or MASM. Thus, MUA and MASM are Not Recommended (I), Moderate Confidence for treatment of acute, subacute, or chronic LBP.

HOT AND COLD THERAPIES

There is one moderate-quality RCT incorporated into this analysis. [611] Theoretical constructs for heat and cold therapies are rich, for example, cryotherapy purportedly delays or reduces inflammation. [612]

Dogma is also strong for initial acute LBP treatment with ice followed by heat, yet quality supportive evidence is absent. Many believe the primary purpose of these treatments is distraction. There are no quality studies of cold or cryotherapy. Small moderate-quality trials of a commercial heat wrap device compared, eg, with ibuprofen 400 mg TID suggesting heat is effective, [283, 613–616] although there are no quality trials of heat compared with prescriptions doses of an NSAID or an exercise program.

Heat or cryotherapies are thought to be reasonable self-treatments for moderate to severe acute LBP patients with sufficient symptoms that an NSAID/acetaminophen and progressive graded activity are believed to be insufficient and may be reasonable for treatment of subacute or chronic LBP [617]; however, they are commonly used by patients as a substitute for compliance with active exercise regimens and thus require close monitoring. Self-applications of lowtech heat therapies are Recommended (C) and cryotherapies are Recommended (I), both with Low Confidence. [611]

High-tech devices or provider-based applications of heat and/or cryotherapy are costly, have no quality evidence of efficacy for treatment of LBP and thus are Not Recommended (I), Low Confidence.

There are six moderate-quality RCTs (one with four reports) incorporated into this analysis. [83, 85, 263, 550, 575, 584, 618–620]

Two studies were primarily designed to evaluate the efficacy of manipulative therapies and utilized diathermy as a control group. Diathermy is a type of heat treatment that has been used clinically to heat tissue, is believed to heat tissue deeper than hot packs and heating pads, and has been used to treat LBP. [621]

Yet, its most common use in clinical trials is as a no-effect or low-effect control group. [550, 575, 584] The highest quality trials of diathermy suggest a lack of efficacy, [550, 584] and thus, diathermy is Not Recommended (C), Moderate Confidence for treatment of any type of LBP.

INFRARED THERAPY

There are five moderate-quality studies incorporated into this analysis. [100, 542, 547, 622, 623] Infrared is a heat treatment created by various devices producing electromagnetic radiation in the infrared spectrum.

As available evidence conflicts, [100, 542, 547, 622, 623] there is No Recommendation (I), Low Confidence for or against the use of infrared therapy for treatment of acute, subacute, chronic, radicular or postoperative LBP.

ULTRASOUND

There are one high-qualit [624] and 19 moderate-quality RCTs incorporated into this analysis. [51, 52, 60, 65, 85, 104, 107, 154, 164, 167, 263, 381, 512, 599, 625–629]

Ultrasound has been used for treatment of LBP. [531, 630–633]

There is only one small study, [625] no sizable quality studies of ultrasound for the treatment of LBP, and thus, there is No Recommendation (I), Low Confidence for or against the use of ultrasound for treatment of acute, subacute, chronic, radicular, or postoperative LBP. In situations where deeper heating is desirable, a limited trial of ultrasound may be reasonable for treatment of acute LBP, but only if performed as an adjunct with exercise.

LOW-LEVEL LASER THERAPY

There are three high-quality [634–636] and five moderate-quality studies [264, 623, 634, 637–639] incorporated into this analysis. There are multiple trials of low-level laser therapy available with the highest quality studies having successful randomization mostly indicating a lack of efficacy. [634–637, 639]

Thus, low-level laser therapy is Not Recommended (C), Moderate Confidence for treatment of LBP. [264, 623, 634–639]

ACUPUNCTURE

There are 10 high-quality [640–650] (one with two reports) and 25 moderatequality [273, 396, 511, 623, 637, 638, 651–670] studies (one with two reports) incorporated into this analysis. Trials enrolling only the elderly were not included. [401, 671–673]

Acupuncture has long been used for treatment of LBP. [520, 630, 641, 674–677]

Acupuncture is Recommended (C), Low Confidence for selective use to treat chronic moderate to severe LBP as an adjunct to more efficacious treatments as there is no quality evidence of lasting effects. [273, 396, 511, 623, 637, 638, 640–670]

The Chinese meridian approach is not necessary, as either needling the affected area or sham needle insertion is sufficient. [641, 642, 649] Chronic LBP patients should have had NSAIDs and/or acetaminophen, strengthening and aerobic exercise instituted and have insufficient results.

Acupuncture may be considered as a treatment for chronic LBP as a limited course during which time there are clear objective and functional goals to be achieved and it is an adjunct to a conditioning program with aerobic and strengthening exercise components.

Objective improvements should be shown approximately halfway through the regimen to continue a treatment course. For treatment of acute, subacute, radicular, or postoperative LBP, there are no quality studies, there are other effective treatments for those patients, and thus, acupuncture is Not Recommended (I), Moderate Confidence.

TRANSCUTANEOUS ELECTRICAL NERVE STIMULATION (TENS)

There are five high-quality [678–682] and 25 moderate-quality studies [514, 562, 653, 658, 661, 662, 671, 682–699] incorporated into this analysis.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) has conflicting evidence among the quality studies evaluating the utility to treat chronic LBP. There are studies evaluating TENS for sciatica patients. Of the high-quality studies for chronic LBP, three [678, 681, 682] suggest benefit and two [679, 680] suggest no benefit.

While the highest quality study [682] did find benefit, not all of the higher quality trials did, thus the evidence conflicts. There is no study finding strong evidence of major benefits, thus any benefit appears likely to be modest.

TENS is Not Recommended (I), Moderate Confidence for treatment of acute or subacute LBP or acute radicular pain syndromes. TENS is Recommended (I), Low Confidence for select use in treatment of chronic LBP or chronic radicular pain syndrome as an adjunct to more efficacious treatments. Chronic LBP should be insufficiently managed with prior NSAIDs, aerobic exercise, and strengthening exercise with which compliance is documented. Many providers would also require failure with tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) and/or serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) anti-depressants. TENS (single or dual channel) may be recommended as treatment for chronic LBP when clear objective and functional goals are being achieved which includes objective functional improvements such as return to work, increased exercise tolerance, and reductions in medication use. There is no quality evidence that more complex TENS units beyond the single or dual channel models are more efficacious; thus, those models are not recommended. TENS units should be trialed prior to purchase to demonstrate efficacy and increase function.

MICROCURRENT ELECTRICAL STIMULATION

There is one moderate-quality study incorporated into this analysis for microcurrent electrical stimulation. [700] There are no high-quality and 15 moderate-quality studies incorporated into this analysis for percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. [52, 56, 57, 65, 159, 160, 688, 690, 701–707]

There are no quality studies evaluating H-Wave1 Device (Electronic Waveform Lab, Inc, Huntington Beach, CA) stimulation for the treatment of acute, subacute, or chronic LBP or radicular pain syndromes.

All of the following are Not Recommended (I), Low Confidence: microcurrent electrical stimulation, [700] neuromuscular electrical stimulation (non-chronic pain), and percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (PENS). [52, 56, 57, 65, 159, 160, 690, 701, 702, 705, 706, 708, 709]

There is No Recommendation (I), Low Confidence for or against all of: H-Wave1 Device stimulation therapy, high-voltage galvanic therapy, interferential therapy, [515, 681, 710–715] and neuromuscular electrical stimulation (chronic LBP, chronic radicular pain).

CONCLUSION

Quality evidence to guide the treatment of LBP is available. Detailed algorithms have been developed using the quality evidence where available, with supplementation with the Panel’s expert opinions (ie, consensus guidance).

Acute LBP is best initially treated with directional stretching, progressive aerobic exercise, management of kinesiophobia, and NSAIDs. Work limitations may be needed especially for those with occupational demands exceeding the patient’s abilities; limitations should be gradually eliminated. Adjunctive use of other treatments (eg, muscle relaxants, manipulation) may be added particularly for those with worse and/or persistent pain. There may be some patients for whom initial treatment with manipulation may be effective, however, if there is not rapid improvement with manipulation, it is recommended that the primary focus should change to progressive exercises.

Other treatments with some evidence of efficacy include self-applied heat therapy. Failure of LBP to rapidly improve should necessitate an early search for, and treatment of other factors, including kinesiophobia and other psychosocial factors.

Patients with radicular pain syndromes should be treated with maintaining activity as able, stretching, aerobic exercise, and NSAIDs. A course of oral glucocorticosteroids has some evidence of efficacy, although the Panel vote was split in large part based on the risk-benefit ratio driven by potential adverse effects. Ongoing or progressive neurological deficits require other treatment.

Patients with chronic LBP require institution of a program that primarily emphasizes functional restoration including aerobic exercise, strengthening exercises, and kinesiophobia. Cognitive behavioral therapy and functional restoration also have evidence of efficacy. Medications with evidence of efficacy include NSAIDs, norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor anti-depressants, and mixed SNRIs.

Massage, manipulation, and acupuncture have some indications as adjunctive treatments; however, the emphasis should be on functional restoration. In no case should treatments be cumulative without ascertaining incremental functional benefits; instead, ineffective treatments should be discontinued after trialing.

Treatment Algorithms

Low Back Algorithm 1 Initial Evaluation of Acute and Subacute Low Back and Radicular Pain

Low Back Algorithm 2 Initial and Follow-up Management of Acute and Subacute Low Back

and Radicular Pain

Low Back Algorithm 3 Evaluation of Subacute, Chronic, or Slow-to-Recover Patients with

Low Back Pain Unimproved or Slow to Improve (Symptoms >4 Weeks)ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the assistance of the Research Team at the University of Utah’s Rocky Mountain Center for Occupational and Environmental Health without whichthis work would not have been possible. Team members include: Jeremy J. Biggs, MD, MSPH, Matthew A. Hughes, MD, MPH, Matthew S. Thiese, PhD, MSPH, Ulrike Ott, PhD, MSPH, Atim Effiong, MPH, Kristine Hegmann, MSPH, CIC, Alzina Koric, MPP, Brenden Ronna, BS, Austen J. Knudsen, Pranjal A. Muthe, Leslie M.C. Echeverria, BS, Jeremiah L. Dortch, BS, Ninoska De Jesus, BS, Zackary C. Arnold, BS, Kylee F. Tokita, BS, Katherine A. Schwei, MPH, Deborah G. Passey, MS, Holly Uphold, PhD, Jenna L. Praggastis, BS, Weijun Yu, BS, Emilee Eden, MPH, Chapman B. Cox, Jenny Dang, BS, Melissa Gonzalez Amrinder Kaur Thind, Helena Tremblay, Uchenna Ogbonnaya, MS, Elise Chan, and Madison Tallman.

References:

Return to LOW BACK GUIDELINES

Since 3-10-2020

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |