Nonspecific Low Back Pain and Return to Work This section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Am Fam Physician. 2007 (Nov 15); 76 (10): 14971502 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Trang H. Nguyen, MD, and David C. Randolph, MD, MPH

University of Cincinnati College of Medicine,

Department of Environmental Health,

Milford, Ohio 45150, USA.

dococcmed@aol.com

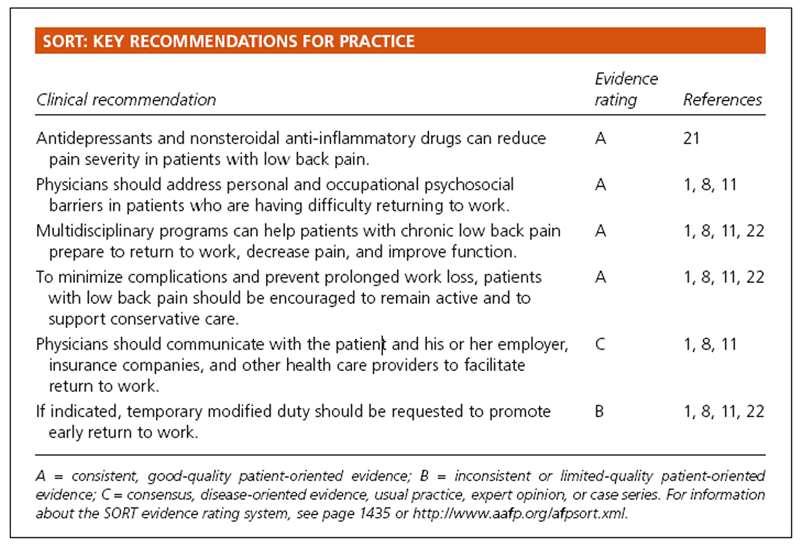

As many as 90 percent of persons with occupational nonspecific low back pain are able to return to work in a relatively short period of time. As long as no "red flags" exist, the patient should be encouraged to remain as active as possible, minimize bed rest, use ice or heat compresses, take anti-inflammatory or analgesic medications if desired, participate in home exercises, and return to work as soon as possible. Medical and surgical intervention should be minimized when abnormalities on physical examination are lacking and the patient is having difficulty returning to work after four to six weeks. Personal and occupational psychosocial factors should be addressed thoroughly, and a multidisciplinary rehabilitation program should be strongly considered to prevent delayed recovery and chronic disability. Patient advocacy should include preventing unnecessary and ineffective medical and surgical interventions, prolonged work loss, joblessness, and chronic disability.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

The management of low back pain and determining the patient's safe return to work are common issues encountered by family physicians. Challenges include unfamiliarity with the patient's job demands, complex workers' compensation systems, and a vast array of diagnostic and therapeutic interventions with questionable effectiveness and value.

The objectives of this article are to encourage conservative care in patients with occupational nonspecific low back pain (i.e., pain occurring predominantly in the lower back without neurologic involvement or serious pathology [1]), to promote early return to work, and to prevent prolonged disability.

Epidemiology

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, there were 4.2 million nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses reported by private industries in 2005. [2] Sprains and strains accounted for approximately 42 percent of injuries and illnesses requiring time away from work. [2] The body part most often involved in these injuries was the trunk, and 63 percent of injuries to the trunk involved the spine. [2]

Cost

Workers' compensation systems cover 127 million U.S. workers.3 The estimated annual cost for all occupational injuries and deaths is $128 billion to $155 billion, [4] and the estimated annual cost for back pain is $20 billion to $50 billion. [5] Lumbar injuries result in approximately 149 million lost work days per year; about two thirds of these days are caused by occupational injuries.6 The annual productivity losses resulting from lost work days are estimated to be $28 billion. [6]

From 1991 to 2001, individual indemnity and medical costs increased by 39 percent and 62 percent, respectively, despite significant decreases in the rates of injuries and illnesses and in the number of lost work days. [7] In addition, patients covered by workers' compensation plans have more office visits, hospital admissions, treating physicians, diagnostic referrals, and therapeutic procedures, and longer duration of care compared with patients covered by other forms of insurance. [7]

Factors that may contribute to these rising costs include lack of managed care involvement, patients' freedom to choose their treating physician, lack of deductibles and copayments, increased cost of prescription drugs, and an increased number of persons who continue to work into their retirement years. California's workers' compensation data from 1993 to 2000 indicated that indemnity costs increased eightfold when there was legal involvement. [7]

Prognosis

Most patients with low back pain recover within four to six weeks, [8] and 80 to 90 percent improve within three months regardless of treatment modality. [5, 9] However, the 10 percent of patients who develop chronic low back pain (i.e., pain lasting more than three months) account for 65 to 85 percent of the costs. [5, 6] After an episode of nonspecific low back pain, 20 to 44 percent of patients have a recurrence within one year, and up to 85 percent have a recurrence during their lifetime. [811]

Risk Factors

The cause of low back pain cannot be clearly identified in 90 percent of patients. [9, 10] Some physical demands, including manual lifting, bending, twisting, and whole body vibration, are associated with an increased likelihood of low back pain. [11] It should be noted that association is not equivalent to causation. However, there is strong evidence that personal and occupational psychosocial variables play a more important role than spinal pathology or the physical demands of the job. [11] The strongest predictor of future low back pain is a history of such pain. [11]

RISK FACTORS FOR DELAYED RETURN TO WORK

Table 1 Psychosocial variables, both personal and occupational, are strong risk factors for work absenteeism and chronic disability (Table 1). [8-10, 12] It is unclear which factors are most important. [9, 10, 13] Lifting requirements at work and the unavailability of modified duty can delay early return to work. [10, 14]

Patients older than 50 years are more likely to have prolonged, severe low back pain and are less likely to respond to treatment. This population is also at higher risk for chronic disability. [11, 12]

Assessment of Patients with Occupational Back Pain

The quality, anatomic location, severity, duration, and frequency of symptoms such as pain, numbness, paresthesias, and weakness should be documented. Symptom onset and duration, factors that make symptoms better or worse, and any interference with activities of daily living should be described. The patient's job title and description of duties are also relevant, as is current work status (i.e., with or without restrictions) and determining whether the patient has sought care elsewhere.

Table 2 The patient's medical history is important and should include patient's age, comorbidities, medication use, and history of diagnostic testing and response to treatment for low back pain. [1, 8] Red flags should be kept in mind when determining the need for further diagnostic studies (Table 2). [1, 8] The physical examination should be thoroughly documented to rule out serious spinal pathology. [1, 11]

Imaging studies have limited value in the assessment of patients with nonspecific low back pain. There is strong clinical evidence that radiography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings do not correlate with clinical symptoms of nonspecific low back pain or a patient's ability to work. [9, 11, 15] MRI and other imaging studies should be reserved for patients with radicular symptoms who fail conservative care and those with worsening neurologic findings, objective weakness, uncontrolled pain, or suspected cauda equina syndrome. [8]

Treatment of Chronic Low Back Pain

Treatments that may improve outcomes in patients with chronic low back pain include analgesic and anti-inflammatory medications, and massage in combination with exercise and patient education. [9, 16] Treatments for which evidence of effectiveness is unclear include acupuncture, epidural steroid injections, muscle relaxants, spinal manipulation, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, trigger point injections, heat therapy, and therapeutic ultrasound. [9, 1720] Antidepressants reduce pain intensity, but do not improve the ability to perform activities of daily living. [21]

Electromyography biofeedback, shortwave diathermy, botulinum toxin type A (Botox) injections, facet injections, prolotherapy, tractions, and lumbar braces and supports are not beneficial and are not recommended. [1, 9, 22]

Bed rest should be limited to less than two days. [8, 11] Patients should be encouraged to remain as active as possible. [1, 8, 11] Exercise conducted under the supervision of a therapist three to five times per week is highly recommended as first-line therapy in the treatment of low back pain. However, there is conflicting evidence as to which type of exercise therapy is most effective. [8, 22] As treatment progresses, passive modalities should decrease and active modalities should increase, and the number of exercise sessions per week should be tapered. Home exercises should be initiated with the first therapy session and regularly assessed for compliance. The patient's status in therapy should be reevaluated after the first six visits (i.e., in about two weeks). If there is no progression, factors that inhibit improvement of pain and activities of daily living should be addressed, and multidisciplinary rehabilitation should be considered. [22, 23]

Because of limited or conflicting evidence, surgical procedures such as intradiskal electrothermal therapy, spinal decompression, nerve root decompression, or lumbar fusion cannot be recommended for patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain. [1, 22]

Helping the Patient Return to Work

Table A Patients with nonspecific low back pain should be able to work when they are symptomatic. Complete pain relief often does not occur until after resumption of normal activities. [8] It is not necessary for the patient to wait until all pain is eliminated before returning to work. [8, 11] Remaining at work or returning early does not increase the risk of reinjury and can help decrease missed work days, chronic pain, and disability. [8, 11, 22] If work absences occur, they should be brief. [1, 8, 11] Sickness-related absence without clear indications should be avoided to prevent chronicity. [1] The median disability duration for the diagnosis of lumbago is seven days (see Table A for median disability duration for common low back pain diagnoses). [23]

Table 3 lists recommendations for duration of modified duty for patients with lumbago (see online Table B for return-to-work recommendations for additional diagnoses). [23] Initial passive treatments should progress within one week to active exercise and self-care. To continue physical therapy, improvement must be documented. Passive treatments should be minimized. [8]

Table 3 Communication with the patient, his or her employer, insurance company, and case manager can improve clinical outcomes by reducing the adversarial situation, promoting a good worker-employer relationship, and providing an opportunity for the physician to assess the patient's job duties and to request adequate work modifications. [1, 11, 14, 24] Recommending light or modified duty on a short-term basis can decrease work absenteeism (online Table C23). [1, 11, 14, 24]

Workers who have difficulty returning to work after four to 12 weeks may benefit from multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs. [1, 22] Such programs should include an exercise regimen to improve physical conditioning, goal-setting for the patient to return to work, vocational rehabilitation, biopsychosocial interventions, and medication management. These programs, which should be conducted by a team consisting of a physician, a physiotherapist, and a psychologist, [22, 25] can decrease pain, improve function, and prepare the patient to return to work. [22]

Cognitive behavior therapy has been shown to decrease pain intensity and may allow patients with disabling low back pain to return to work sooner. This type of treatment is generally categorized as operant, cognitive, and respondent. The operant approach is positive reinforcement of healthy practices. Cognitive management helps patients to identify and modify beliefs about pain and to control the pain. The respondent strategy teaches patients to use relaxation techniques to alleviate muscular tension. [22] Patients should be encouraged to actively participate in their medical care; this can decrease work absenteeism and lead to a quicker recovery. [1, 8, 11]

Work hardening is physical training specific to the job task. Back schools generally consist of an exercise program and anatomic and functional education about the back. This type of rehabilitation is not recommended because studies have shown that it does not improve pain and function after one year. [22] Use of educational methods based on the anatomy and biomechanics of the back without any other intervention is also ineffective. [11]

Although functional capacity evaluations have been promoted as a way to determine a patient's readiness to return to work, physicians should approach such protocols cautiously. There are no functional test protocols in the United States with established levels of validity and reliability. [24]

Long-Term Complications of Chronic Disability

Family physicians should be aware that labeling a patient as disabled is often not in the patient's best interest. Joblessness and chronic disability are associated with poverty, depression, suicidal behavior, family breakdown, domestic violence, infant mortality, crime, increased cancer mortality rates, and heart disease. [2632] There is strong evidence that if a person misses work for four to 12 weeks, he or she will have up to a 40 percent chance of missing work for the ensuing year. It is unlikely that an employee who misses work for up to two years will ever return to work in any capacity, regardless of treatment. [1, 9, 11, 33]

Author disclosure:

nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jessica Scarf, MS, and Christina Krabacher, MBA, for their assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

The Authors

TRANG H. NGUYEN, MD, is an epidemiology doctoral candidate at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine in Milford, Ohio. She received her medical degree from Louisiana State University School of Medicine, Shreveport, and completed residencies in family medicine at the University of Texas/St. Joseph Hospital, Houston, and in occupational medicine at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine.

DAVID C. RANDOLPH, MD, MPH, is an occupational medicine specialist and a past president of the American Academy of Disability Evaluating Physicians. He currently is an epidemiology doctoral student at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine. Dr. Randolph received his medical degree from Ohio State University School of Medicine, Columbus, and completed occupational medicine training at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

References:

Malmivaara A. Low back pain.

EBM guidelines. Accessed September 5, 2007, at:

http://www.terveysportti.fi/terveysportti/ekirjat_tmp.Naytaartikkeli?p_artikkeli=ebm00435U.S. Department of Labor,

Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses requiring days away from work, 2005.

Accessed September 5, 2007, at:

http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/osh2.pdfGreen-McKenzie J.

Workers' compensation costs: still a challenge.

Clin Occup Environ Med. 2004;4:ix,3958.Schulte PA.

Characterizing the burden of occupational injury and disease.

J Occup Environ Med. 2005;47:60722.Pai S, Sundaram LJ.

Low back pain: an economic assessment in the United States.

Orthop Clin North Am. 2004;35:15.Maetzel A, Li L.

The economic burden of low back pain: a review of studies

published between 1996 and 2001.

Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2002;16:2330.Bernacki EJ.

Factors influencing the costs of workers' compensation.

Clin Occup Environ Med. 2004;4:vvi,24957.Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI).

Adult low back pain. Accessed April 30, 2007, at:

http://www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?doc_id=9863"&"nbr=005287van Tulder M, Koes B, Bombardier C.

Low back pain.

Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2002;16:76175.Manek NJ, MacGregor AJ.

Epidemiology of back disorders: prevalence, risk factors, and prognosis.

Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17:13440.Carter JT, Birrell LN

Occupational Health Guidelines for the Management of Low Back Pain at Work

Occup Med (Lond) 2001;51(2):12435.Proctor T, Gatchel RJ, Robinson RC.

Psychosocial factors and risk of pain and disability.

Occup Med. 2000;15:80312,v.Pincus T, Burton AK, Vogel S, Field AP.

A systematic review of psychological factors as predictors of chronicity/

disability in prospective cohorts of low back pain.

Spine. 2002;27:E10920.Boden LI, Biddle EA, Spieler EA.

Social and economic impacts of workplace illness and injury: current and future

directions for research.

Am J Ind Med. 2001;40:398402.Boos N, Lander PH.

Clinical efficacy of imaging modalities in the diagnosis of low-back pain disorders.

Eur Spine J. 1996;5:222.Furlan AD, Brosseau L, Imamura M, Irvin E.

Massage for low-back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the

Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group.

Spine. 2002;27:1896910.Assendelft WJ, Morton SC, Yu EI, Suttorp MJ, Shekelle PG.

Spinal manipulative therapy for low back pain.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(1):CD000447.Furlan AD, van Tulder MW, Cherkin DC, Tsukayama H, Lao L, Koes BW, et al.

Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(1):CD001351.Khadilkar A, Milne S, Brosseau L, Wells G, Tugwell P, Robinson V, et al.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for the treatment of chronic low back pain:

a systematic review.

Spine. 2005;30:265766.Nelemans PJ, deBie RA, deVet HC, Sturmans F.

Injection therapy for subacute and chronic benign low back pain.

Spine. 2001;26:50115.Salerno SM, Browning R, Jackson JL.

The effect of antidepressant treatment on chronic back pain: a meta-analysis.

Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1924.Airaksinen O, Brox JI, Cedraschi C, et al.

COST B13 Working Group on Guidelines for Chronic Low Back Pain Chapter 4.

European Guidelines for the Management of Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain

European Spine Journal 2006 (Mar); 15 Suppl 2: S192300

See also the archived: European Guidelines Backpain Europe WebsiteMusculoskeletal system and connective tissue.

In: Work-Loss Data Institute.

Official Disability Guidelines. 12th ed.

Encinitas, Calif.: Work-Loss Data Institute, 2007:9901023.Wind H, Gouttebarge V, Kuijer PP, Frings-Dresen MH.

Assessment of functional capacity of the musculoskeletal system in the context

of work, daily living, and sport: a systematic review.

J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15:25372.Meijer EM, Sluiter JK, Frings-Dresen MH.

Evaluation of effective return-to-work treatment programs for sick-listed

patients with non-specific musculoskeletal complaints: a systematic review.

Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2005;78:52332.Dooley D, Fielding J, Levi L.

Health and unemployment.

Annu Rev Public Health. 1996;17:44965.Jin RL, Shah CP, Svoboda TJ.

The impact of unemployment on health: a review of the evidence

[Published correction appears in CMAJ 1995;153:15678].

CMAJ. 1995;153:52940.Lynge E.

Unemployment and cancer: a literature review.

IARC Sci Publ. 1997;(138):34351.Mathers CD, Schofield DJ.

The health consequences of unemployment: the evidence.

Med J Aust. 1998;168:17882.Platt S.

Unemployment and suicidal behaviour: a review of the literature.

Soc Sci Med. 1984;19:93115.Pritchard C.

Is there a link between suicide in young men and unemployment?

A comparison of the UK with other European Community Countries.

Br J Psychiatry. 1992;160:7506.Wilson SH, Walker GM.

Unemployment and health: a review.

Public Health. 1993;107:15362.Williams RM, Westmorland M.

Perspectives on work-place disability management: a review of the literature.

Work. 2002;19:8793.

Return to RETURN TO WORK

Since 4-15-2018

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |