Will Shared Decision Making Between Patients with Chronic

Musculoskeletal Pain and Physiotherapists, Osteopaths

and Chiropractors Improve Patient Care?This section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Fam Pract. 2012 (Apr); 29 (2): 203Ė212 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS S Parsons, G Harding, A Breen, N Foster, T Pincus, S Vogel and M Underwood

Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology,

School of Public Health,

Imperial College School of Medicine,

Imperial College London,

London, UK.

BACKGROUND: Chronic musculoskeletal pain (CMP) is treated in primary care by a wide range of health professionals including chiropractors, osteopaths and physiotherapists.

AIMS: To explore patients and chiropractors, osteopaths and physiotherapists' beliefs about CMP and its treatment and how these beliefs influenced care seeking and ultimately the process of care.

METHODS: Depth interviews with a purposive sample of 13 CMP patients and 19 primary care health professionals (5 osteopaths, 4 chiropractors and 10 physiotherapists).

RESULTS: Patients' models of their chronic musculoskeletal pain (CMP) evolved throughout the course of their condition. Health professionals' models also evolved throughout the course of their treatment of patients. A key influence on patients' consulting behaviour appeared to be finding someone who would legitimate their suffering and their condition. Health professionals also recognized patients' need for legitimation but often found that attempts to explore psychological factors, which may be influencing their pain could be construed by patients as delegitimizing. Patients developed and tailored their consultation strategies throughout their illness career but not always in a strategic fashion. Health professionals also reflected on how patients' developing knowledge and changing beliefs altered their expectations. Therefore, overall within our analysis, we identified three themes: 'the evolving nature of patients and health professionals models of understanding CMP'; 'legitimating suffering' and 'development and tailoring of consultation and treatment strategies throughout patients' illness careers'.

CONCLUSIONS: Seeking care for any condition is not static but a process particularly for long-term conditions such as chronic musculoskeletal pain (CMP). This may need to be taken into account by both CMP patients and their treating health professionals, in that both should not assume that their views about causation and treatment are static and that instead they should be revisited on a regular basis. Adopting a shared decision-making approach to treatment may be useful particularly for long-term conditions; however, in some cases, this may be easier said than done due to both patients' and health professionals' sometimes discomfort with adopting such an approach. Training and support for both health professionals and patients may be helpful in facilitating a shared decision-making approach.

Keywords: Beliefs, health professionals, pain, patients, qualitative

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Background

Chronic musculoskeletal pain (CMP) is a complex and costly health problem, which is treated by a wide range of health professionals [National Health Service (NHS) and private, mainstream and complementary]. [1] Despite the range of treatment options available, it appears to be difficult to treat CMP to the satisfaction of both patients and health professionals. [2] As part of a programme of research exploring the process of care for CMP, we undertook a systematic review in which we reviewed studies exploring the influence of patientsí and health professionalsí beliefs and expectations about CMP and its treatment on the process of the primary care consultation. [3] Within this programme of work, we defined the process of care as looking at the patientsí perception of their problem, its management and the dynamic interaction between the condition, the patientsí perception and the practitionersí influence. [4]

Within the review, we found that the eligible studies primarily focused on GPs and that the lack of satisfaction reported by patients and health professionals may be due to both incorrectly Ďsecond-guessingí one anotherís expectations, presenting mismatching understandings of the patientsí pain to one another and perceiving that each is making unrealistic demands. [3] Therefore, we found that the majority of previous work had mainly explored the GP perspective despite a wide range of physical therapists also being consulted by patients with chronic pain, and so, we felt that it would also be important to explore the perspectives of these practitioners.

Within this study, we aimed to explore patients and chiropractors, osteopaths and physiotherapistsí beliefs about CMP and its treatment and how these beliefs influenced care seeking and ultimately the process of care.

Within this paper, we have focused on exploring themes about the overall process of care rather than on patientsí experiences of receiving care from a particular professional group.

Design and methods

This was a qualitative study of patients reporting unspecified CMP and of NHS and private physiotherapists, osteopaths and chiropractors. We took a phenomenological approach to the research. We defined unspecified CMP as long-lasting pain, which lacked specific pathological features. In-depth interviews and focus groups were undertaken with both patients and health professionals.

Samplingópatients

We sampled patients from responders to a population survey of CMP. [5] We surveyed 330 randomly selected patients from each of 16 Medical Research Council General Practice Research Framework practices in the south-east quadrant of England.

GPs excluded patients who had(i) terminal illness,

(ii) severe psychiatric disorder or dementia,

(iii) if the patient had requested not to be involved and

(iv) if the GP considered it inappropriate for the patient to be involved.We left this final criteria open to allow the GP to use their knowledge of the patient to identify any patient for reasons other than the three specified reasons who they would prefer us not to approach.

All participants received a postal questionnaire, with two reminders, in which they indicated whether they would be willing to take part in the qualitative study.

Box 1

Box 2

We conducted two focus groups with general practice patients with CMP, to map out the issues of importance to them. The data from these groups were used to further develop and refine our topic guides for both patients and health professionals (see Boxes 1 and 2).

For the patientsí in-depth interview study, we selected a purposive sample of 15 patients using age, gender, pain severity, pain location and care seeking behaviour as our sampling criteria to enable us to capture a broad range of experiences.

Samplingóhealth professionals

We developed a sampling frame by sending a short survey to random samples of osteopaths, chiropractors and physiotherapists (both NHS and private) based in the south-east quadrant of England, selected from their professional registers. The questionnaire solicited their age, gender, years since qualification, experience of treating patients with CMP and their willingness to be interviewed.

We held a focus group with eight health professionals, which allowed us to map the issues of importance to them. Data from this group were used to further develop and refine our topic guide for both patient and health professional interviews. For the interview study, we selected a purposive sample of NHS physiotherapists, private physiotherapists, osteopaths and chiropractors.

Approaching interviewees

Prior to approaching patients, we asked their GP to confirm that this was appropriate. Each potential interviewee (patients and health professionals) was sent a covering letter and information sheet detailing the study and their involvement and was contacted after one week to determine whether they were willing to be interviewed. Written informed consent was obtained at the beginning of the interview.

Interview process

Topic guides were developed for both the focus groups and the in-depth interviews, from our systematic review of this area, from brainstorming within the research team and by using the data from both the patient and the health professional focus groups (Boxes 1 and 2).

Box 3

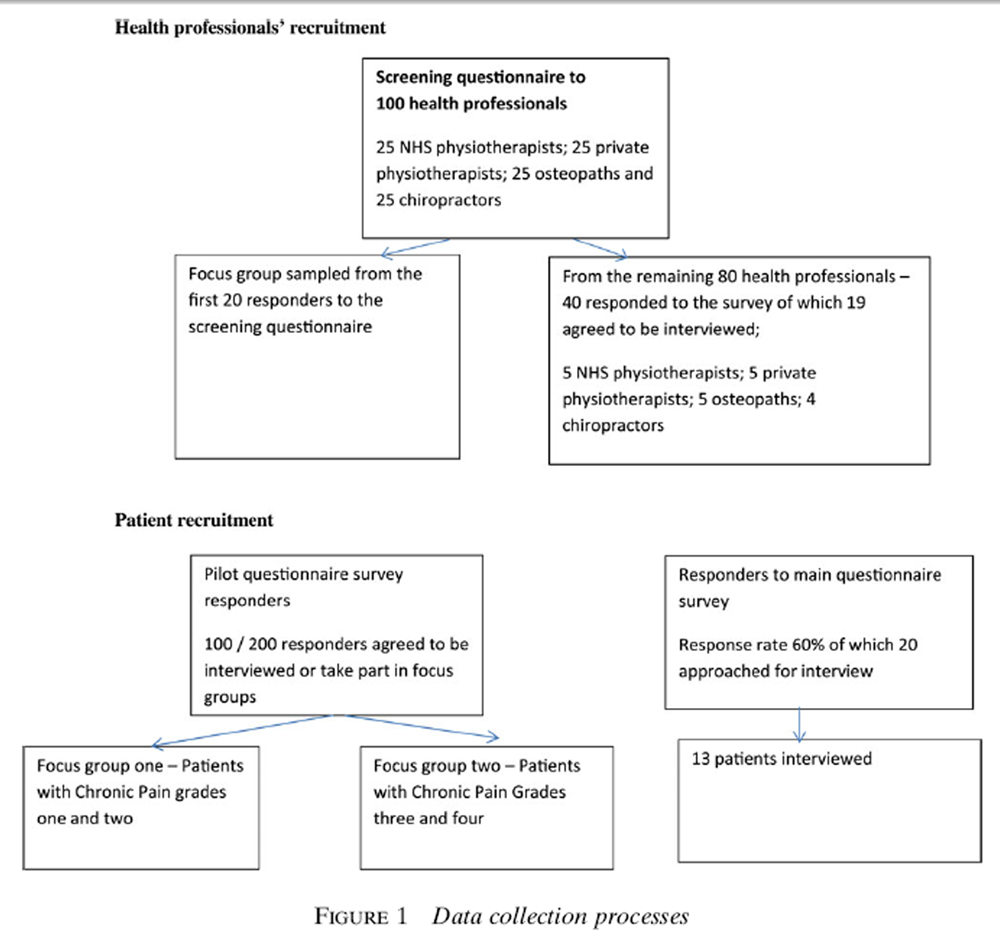

Figure 1 For the health professionalsí interviews, patientbased scenarios were developed by the study authors, to explore their beliefs about the management of chronic pain (Box 3). The scenarios depicted a Ďtypicalí patient with chronic pain and were designed to act as a trigger for health professionals to explore how they would treat the patient described in the scenario and their beliefs about patientsí beliefs about the pain and its treatment. All interviews were audio taped and transcribed with the intervieweesí permission.

Within our data collection, where possible, we tried to achieve data saturation and so were there were no new themes occurring, we halted our data collection. However, we also had to bear in mind the resources available to undertake the study, which also influenced the data collection process. The process of data collection is described in more depth in Figure 1.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using the Framework method, with the analysis being further informed by the application of social theory. [6, 7] We used this method as it allows data to be managed and analysed transparently within a large research team. We used the topic guides as our starting point of a priori codes and then SP along with other members of the research team (GH, SV and NF) independently read through the transcripts and identified recurrent themes, which were used along with the a priori codes from the topic guides to develop the thematic framework. This framework was applied to the data and further refined where necessary. We identified emerging themes from the data by reading through transcripts, listening to recordings and coding by hand. We then compared these codes to the a priori framework and adapted it accordingly. Coding was also undertaken independently by a number of the team members. We then met to compare our coding and identify and discuss any areas of discrepancy. On the whole, we tried not to reach consensus but instead tried to identify, explore and document the various range of interpretations of our data.

We used EXCEL to develop charts for each group of participants, which allowed for both within and across case analysis. These charts were organized around the themes and subthemes enabling both within and between case analyses. A key element of our approach to analysis was the multidisciplinary research group discussing their own beliefs about the issues being studied and how these beliefs might influence the process of data collection. We also revisited these discussions during our regular team meetings. With regard to how, we analysed the different types of data that we collected (focus group and in-depth interview, health professionals and patients). We analysed the focus groups for both health professionals and patients initially to help further develop the topic guides for the in-depth interviews with both groups. However, we also compared the themes identified in the focus groups and in-depth interviews to check that we were covering all of the areas. We initially analysed the patient and health professional data separately (both focus groups and in-depth interviews) comparing both within and across cases, and finally, we then compared our findings from the patient and health professional data.

Results

Table 1

Table 2

Table 3

Table 4

Table 5 We obtained a 60% response rate (2504/4171) to the questionnaire survey. [5] Three hundred and thirteen patients had Chronic Pain Grades III and IV and of these, 69% (217) agreed to be interviewed. [8] Twenty-two patients from the responders to the survey within the study pilot practice took part in the focus groups (Tables 1 and 2). Thirteen patients with CMP drawn from responders to the population survey agreed to be interviewed (Table 3). One hundred health professionals were approached (25 private physiotherapist, 25 NHS physiotherapists, 25 osteopaths and 25 chiropractors). The first 20 respondents were approached to participate in the focus group (Table 4). Of the remaining 80 approached, 40 agreed to be interviewed, and from these 40, we sampled 19 health professionals who were interviewed (Table 5).

We identified the following themes related to the process and outcomes of the consultation:a) The evolving nature of patients and health professionalsí models of understanding CMP;

b) Legitimating suffering and

c) Development and tailoring of consultation and treatment strategies throughout patientsí illness careers.The evolving nature of patients and health professionalsí models of understanding CMP

Patients and health professionalsí beliefs about pain causation. Patients and health professionals incorporated both physical and psychological models into their understanding of CMP. Physical models included joints wearing out and acute injuries not being managed properly leading to CMP. Psychological models included the influence of stress on both causation and exacerbation of pain and the acceptance of pain. The extent to which physical or psychological models were evoked appeared to be influenced by the length of time that patients had experienced pain for and the length of time that the health professional had been treating the patient for. It was also influenced by the extent to which patients had strong biomedical views about causation compared to those who were more willing to accept psychological explanations. Those who were more accepting of the psychological models of causation appeared to be more positive about developing coping strategies to manage their pain and those espousing a particularly vehement biomedical perspective seemed to be more likely to consult further to find a cure for their pain. The quote below, however, demonstrates a third approach of not trying to identify causation as long as you were able to do what you wanted to do within your life.I seem to have always had back pain of some description, whether it stems from when I had my son, I donít know. The doctor says its wear and tear. Iím not a person who delves into things too much if I can cope.

(Patient eleven: Female aged 72)

Patientsí adaptation of causation beliefs.

Patientís ideas about pain causation appeared to be influenced by their perception of themselves and their beliefs about how their health should be at a particular age. For example, older patients appeared more accepting of their pain seeing it as a part of growing old, whereas this quote from a younger person demonstrates how she felt that she had had to rather grudgingly accept her pain and the damage to her body.They said, when youíre about 70 you will stabilise as your back gets more. I thought fine; Iím only 30! And I just thought well itís gonna take time to get better and it did and so I got back to normal but thereís nothing else they can do, they canít operate or you know, canít put back the damage, its done

(Patient nine: Female aged 39)Patients described how they adapted their causation beliefs as their problems persisted, and as they were introduced to new ideas, when they consulted a range of different health professionals. Some patients initially related their problems to physical dysfunction, but subsequent consultations made them question particularly if they were provided with alternative explanations. The extent to which patients accepted or rejected these explanations depended on how congruent they were with their original beliefs. The quote below describes the experiences of a patient who felt that her experiences with a chiropractor had not been particularly useful and how the approach of a physiotherapist felt more congruent with her belief system.

I saw the chiropractor because it was getting to the point where I just couldnít live with the pain, he said my pelvis is twisted and he pulled this and twisted that and it didnít do me any good at all. And then someone said have you tried physiotherapy, which I had, but this woman, she believed that exercise was the way out of the pain, not just to treat it. And literally doing the exercises she gave me pulled me out of the pain

(Patient twelve: Female aged 36)An alternative interpretation of this quote may be that patients may adopt a model retrospectively in order to support interventions that they found useful.

Health professionals Ďadaptation of causation

beliefs. Most of the health professionals reported how they adapted their beliefs when they became more experienced at managing CMP patients. For example, where once they had prioritized physical explanations, they now also recognized psychological explanations. Others reported how they recognized both the physical and the psychological aspects of patientsí pain but that the extent to which they prioritized one aspect over the other depended on their perceptions of patients and their beliefs about their own abilities to manage certain aspects of patientsí pain. However, despite recognizing the potential for psychological explanations for patientsí pain, not all the health professionals interviewed were comfortable with managing these aspects and did not feel that it was within their remit.I think itís fine saying yes, well you know that is part of the pain, you know if it makes you feel down at the time, you feel depressed with it. I donít really feel Iím at all competent in knowing what to say to try and help them round that

(Private physiotherapist ó Female)Patients and health professionals appear to incorporate both physical and psychological models into their explanations of CMP, but the extent to which one or both of these explanations are evoked is likely to change during the process of providing and seeking care for CMP. This emphasizes the importance of health professionals ascertaining the belief systems of patients regarding their CMP to ensure that the approach taken to treatment is congruent with their beliefs and to revisit patients and their own beliefs regularly throughout the course of treatment, to ensure that any decisions made about the care provided are shared between patients and health professionals, which should hopefully increase the success of treatment options.

Legitimating sufferingPatientsí beliefs about receiving a diagnosis/label for their pain. Many of the patients interviewed felt as their pain did not have a specific cause that they were under pressure to convince their health professionals that their problem was real. This need to obtain legitimation for their pain may have been a key reason for patients continuing to consult a wide range of different health professionals for their pain.

Health professionalsí beliefs about being able to diagnose CMP. Many of the health professionals interviewed felt under-confident about the identification and management of the psychological aspects of pain, which may have impacted negatively on the degree of trust that patients had in them. It may have also increased some patientsí feelings of delegitimation if they were presented with a psychological explanation for their pain, which their health professional did not appear to be comfortable in managing. Health professionals also spoke about how they wanted to be trusted by their patients and about the pressure they felt to provide a diagnosis for patients who had been unable to obtain a diagnosis prior to consulting them. They spoke about how immediately they felt that they might have little different to offer such patients and how this could impact negatively on their relationships.Oh, the other one just we can get, you reminded me caricatures of patients are the people whoíve been everywhere you know they come and they say uh "I donít think thereís anything you can do um, but Iím here anyway. Iíve been to see a Dr X, rheumatologist, Dr X, orthopaedic surgeon, Dr," this, doctor that, doctor the other. The chiropractors, the physios, the acupuncturists, the homeopaths, the faith healer. And now Iíve come to see you, and I just think well you know. I know that next week youíre gonna be saying "And I went to see the osteopath," X, "and he was no good, he didnít help me either."

(Male osteopath)But I think itís hard, I think itís very hard addressing, itís fine saying yes well you know that is part of the pain, you know if it makes you feel down at the time, you feel depressed with it. I just donít know how to, I donít really feel Iím at all competent in knowing what to say to try and help them round that without. And I think people as you say, if people have been referred to a clinical psychologist or something like that they, I think they do definitely feel very much you know oh my God itís in my head or whatever

(Private physiotherapist)

The interaction between patientsí and health professionalsí beliefs about pain causation.

We found that there was some dissonance between patients and health professionalsí beliefs about the psychosocial aspects of care, which appeared to impact both on the legitimation of pain and on the degree of trust within the patientóhealth professional relationship. Patients appeared to want emotional support from their health professionals to help them to cope with their CMP. They did not always appear to be comfortable with instead being offered psychological explanations for their pain and in some cases felt that this delegitimated their suffering.Well yeah, I didnít see any reason why (the pain) shouldnít go, because initially they tend to say, well thereís nothing wrong and they take an X-ray, an ordinary straightforward X-ray and say well thereís nothing wrong, so you think itís all in here (gestures to head) itís all in the mind, so then the self blame starts so that adds to the depression bit as well

(Patient two)

Legitimation of suffering.

Therefore, legitimation of both suffering and of the course of action decided upon by a health professional appeared to be key within this study. Patientsí wanted a diagnosis to legitimate their pain, and in some cases, health professionals wanted their clinical judgement that the patientsí pain was unspecified to be trusted. The identification and management of the psychological aspects of CMP appeared to be important when considering the issue of legitimation of suffering as many patients wanted emotional support and not to be provided with a psychological explanation of their pain in place of a physical diagnosis. Health professionals reported discomfort with and lack of confidence in managing the psychological aspects of pain may mean that patients might not obtain an explanation of the psychological aspects of their pain, which makes sense to them and does not make them feel that their suffering is being dismissed.

Patientís need to be trusted and believed regarding the legitimacy of their pain should be at the forefront of health professionalís minds during their consultation. The health professional groups included in this study may also need further training regarding the management of their psychological aspects of pain, particularly in not labelling patientsí need for emotional support in the management of their pain as a need for psychological treatment.

Development and tailoring of consultation and treatment

approaches throughout patientsí illness careers

Patientsí beliefs about consulting for and treatment of CMP. For patientsí at the heart of sustained relationship with a health professionals appeared to be a shared consensus over the underlying cause of the patientsí pain as patients appeared to consult health professionals models of causation were congruent with theirs. If their health professionals did not hold similar models of causation to them, then patients were likely to discontinue their relationship and either try to identify someone whose beliefs were similar to theirs or go down a self-management route.I think thatís the first line of defence for the GP is pain relief. Letís get rid of the pain and that will be it, but of course it can go on for so long that the stuff thatís used for pain relief makes you ill in itself. So then you are back thinking, well thatís not going to work, I canít keep taking this, Iíve got to find something else, so you start looking at alternatives well anything. I mean Iíve even got a blinking Zimmer frame out in the garage and aids, things to help you pick things up and when you are looking at those sorts of things thatís very depressing. Because with these possibly small injuries, relatively small itís causing absolute havoc with your body and your life. So you can go from losing hoping to thinking well letís get on top of this and do something about it so your expectations of help from other people rapidly dry up.

(Patient two)Other influences on patientsí consulting strategies where the lay referral network and the patientsí perceptions of their self-identity. In terms of the lay referral network, patients were more likely to take notice of recommendations if they had observed that a particular treatment had been successful for a friend, and in terms of patientsí self-identity, patients who had previously been active and were no longer able to achieve their previous level of function may have perceived their problem to be greater than someone who was previously inactive. Finally, another influence on care seeking related to the individual was the extent to which they were willing to take responsibility for their problem.

Health professionalsí beliefs about consulting for and treatment of CMP.

Health professionalsí beliefs about consulting for and treatment of CMP. In many ways, health professionalsí beliefs about patientsí consultation strategies appeared to mirror patientsí beliefs. In that, they believed that some patients were unlikely to seek care as they had adapted to their pain, whereas others would consult more as they were finding it more difficult to adapt to their pain as it had become a key part of their identity/biography which needed managing. Health professionals felt that a large part of their role was to help patients manage their unrealistic expectations of care.We try to move as far away as we can from hands-on dealing with people, with the chronic patients, I mean a lot of them, they come with a folder of all of the places they had been to, all the tests that theyíve had. So you just have to start at the beginning and say realistically, weíre not going to make your pain go away

( NHS physiotherapist)Health professionals also felt that the degree to which patients were willing to take responsibility for their condition impacted on their care seeking. They reflected on how responsibility for care seeking appears to exist along a continuum, from responsibility lying solely in the hands of the patient, through to the patient completely abdicating responsibility for care seeking decisions to health professionals.

Youíve got to get you and the patient on the same side facing the problem and not become identified with the problem. And thatís when people become dissatisfied; itís when they associate the problem and the doctor together. And to some extent I guess youíve got to get the patient to own the problem as well as take some responsibility

(Male osteopath)

Adaptation and tailoring of consulting strategies.

Patients developed and tailored their consultation strategies throughout the course of their illness careers. The development of their consultation approaches appeared to be influenced by their developing models of causation of CMP, their continued need for legitimation of their problem, their contact with a lay referral network and their individual characteristics such as their willingness to take some responsibility for managing their health problems. Patients also reflected on how the nature of their expectations changed as they continued to consult, for example, they reported on how their expectations were lowered as they gained more experience of consulting and that their expectations changed from cure or diagnosis to obtaining symptom relief. Despite this, there was a sense from patients that although they had accepted that obtaining a cure was highly unlikely, that they had not completely relinquished all hope of obtaining one.

Discussion

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The non-directive exploratory approach taken to the interviews allowed the process of care to be described by patients and health professionals in their own words, and using framework to analyse, the data increased the transparency of the data analysis process and allowed us to involve the multidisciplinary research team in the analysis and interpretation of the data more easily. [6, 9] We were able to incorporate the multidisciplinary teamís own perspectives on these issues into the analysis process by ensuring that they all had some involvement in the process, with data and interpretations of the data being discussed at a regular basis within the research team meetings.

Undertaking a systematic review of studies exploring the process of primary care for CMP provided us with a method of determining what may be the issues of importance to explore in our qualitative studies. [3] It also helped us to identify that the majority of previous work in this area had been undertaken with GPs and that it might be important to also explore the views of other key health professional groups involved in caring for patients with CMP.

We used a combination of focus groups and indepth interviews within the study, which was invaluable in terms of both scoping out the issues of importance to explore in more depth within the in-depth interviews, and it also enabled us to triangulate data from the focus groups and in-depth interviews. On the whole, we did find similar issues raised in the in-depth interviews as were raised in our earlier focus groups, which gave us some confidence that we were exploring the majority of the key issues within this area. The discrepancies where mainly in terms of a wide range of perspectives on particular issues being identified within the in-depth interviews.

In terms of the study weaknesses, we would have liked to interview individual patients and a sample of the health professionals whom they consulted, to discuss actual care seeking and care delivery experiences from the perspectives of the patients and health professionals involved in the interaction. This would have added another dimension to the data. Therefore, it will be important for future research to match patient and health professional data over time. A further limitation of this study was that we were just able to interview patients and health professionals at one time point, a more useful approach may be to recruit a qualitative prospective cohort to explore changes in models over time.

We identified our study participants from the responders to a population questionnaire survey. In some respects, this was a strength of the study as we were able to identify a wide range of patients in terms of both demographic characteristics and consulting strategies; however, we were limited to the responders to the questionnaire survey. The questionnaire survey responders were more likely to be older, white and to have completed their education at 16 years of age. Therefore, we were less able to sample patients from ethnic minority groups, younger people and those with higher education levels who may have a different approach to their care seeking.

In terms of our sampling of health professionals, we approached 80 health professionals, of which 40 agreed to participate and we sampled 19 from this group of 40. In the main, we gained a good response to our screening survey, although it is possible that those who responded may have had a particular interest in this area.

Discussion of findings

The systematic review we undertook as part of this work demonstrated how many CMP patients expressed some dissatisfaction with their GP care, which may have been a driver for them to seek care elsewhere. 3 The findings from this study confirmed this. Patientsí dissatisfaction appeared to be rooted in their GPs perceived inability to get to the root cause of their problem and in them feeling that they were not given enough treatment choices.

Within this study, we were exploring the process of care for CMP. A process by definition is not static but fluid and perhaps, this may need to be taken into account by both patients and health professionals when seeking and providing care for CMP. In that patients, will be seeking care on a long-term basis for a chronic health problem such as CMP and that they and their health professionalsí views and beliefs about their condition will be likely to change throughout the process of their care and may need to be revisited on a regular basis to ensure that treatment and management of the patientsí condition is working from both the patientsí and the health professionalsí perspectives. For example, we found that patients and health professionals incorporated both physical and psychological models into their explanations of CMP but that the extent to which one or both of these explanations are evoked was likely to change during the process of care. We also found that patients wanted to have ongoing emotional support to help them to manage their CMP and the effects on their lives but that health professionals often misconstrued this need for emotional support as a need for psychological treatment. Patients appeared to want to establish relationships with health professionals who they could trust and who they could get involved in the joint management of their condition. Therefore, it seems reasonable to suggest that longterm conditions such as CMP may require both patients and health professionals to invest more in their relationships than for other more acute conditions.

However, this may be difficult though due to the current models of care seeking that patients appear to be adopting, in that their dissatisfaction with their GP is in some cases driving them to seek care (often on a short-term basis due to financial reasons) from a wide range of health professionals, where they are looking for an answer and a cure for their condition rather than developing a strategy for its management alongside a trusted health professional.

A good starting point may be to work to improve the relationship between such patients and their GPs or with whichever health professional the patient feels most comfortable with. With this relationship being based on mutual respect, which will allow the patients and their health professional to continually revisit their own beliefs about pain causation and its treatment throughout the process of patientsí care. Key aspects of the relationship that may need to be improved upon are both patientsí feelings of delegitimation with regard to pain causation and health professionalsí feelings of being distrusted by patients because they are unable to provide a cure or a solution to their pain. Health professionals (particularly the groups included in this study) may also require further training on the identification and management of the psychological aspects of CMP, so that a patientsí need for emotional support is not misconstrued and those with a need for psychological intervention can be readily identified. Egeri et al. also found, in a study of patients with fibromyalgia that as patients often feel disempowered by their interactions with their clinicians that working with patients to identify ways in which their relationships with clinicians can be improved may be invaluable in improving the quality of their care. They concluded that there was a need for supportive, empathetic care and increased knowledge among health professionals of the alternative treatment options. [10]

A shared decision-making approach is likely to be the most appropriate for long-term conditions, where both patient and health professionals feel able to openly discuss their concerns and views with one another, their beliefs about their pain and the suggested courses of action with regard to treatment. Within such an approach, patients and health professionalís expectations of one another and of the treatment process could also be usefully explored on a regular basis. Allegretti et al. in their study of chronic low back pain concluded that it may be important to reconceptualize doctors and low back pain patients as a single teachable unit with regard to the management of back pain, which provides further support for the suggestion that improving the relationship between patients and health professionals may be key to the improvement of CMP management. [11] Health professionals may need to facilitate patientsí understanding of their condition and their involvement in its management as soon as possible in their illness career. Patients and health professionals working together may help to increase levels of trust and prevent both the patient consulting with unrealistic expectations and the health professional feeling that they cannot possible meet these expectations. A randomized controlled trial of a shared decision-making intervention undertaken by Bieber et al. found that although there was no improvement in pain scores that both patientsí and providers believed, their subsequent clinical encounters to be more productive and less difficult. Patients reported feeling more understood and practitioners reported having fewer negative feelings about their patients. [12]

However, this may be easier said than done. Health professionals may also need to assess patientsí level of comfort with adopting a shared decision-making approach to their care and they may also need to assess their own level of comfort with adopting such an approach. For example, a study by Teh et al. found that older adults varied in their willingness to be involved in their treatment decisions, with some preferring to let the provider make the decisions and others participating by asking for or refusing particular treatments. [13] However, regardless of the approach taken by patients, it was concluded that it was important to have a mutually respectful relationship between patient and provider. Training may be required for both health professionals and patients to help them to take a shared decision-making approach and to understand the likely benefits for patient care.

Conclusions

Seeking care for any condition is not static but a process particularly for long-term conditions such as CMP. This may need to be taken into account by both CMP patients and their treating health professionals, in that both should not assume that their views about causation and treatment are static and that instead they should be revisited on a regular basis. Adopting a shared decision-making approach to treatment may be useful particularly for long-term conditions; however, in some cases, this may be easier said than done due to both patientsí and health professionalsí sometimes discomfort with adopting such an approach. Training and support for both health professionals and patients may be helpful in facilitating a shared decision- making approach.

Funding:

Arthritis Research Campaign, now Arthritis UK.

Ethical approval:

The London Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee provided ethical committee approval. All relevant LRECS were informed that the study was being undertaken and I held an honorary contract with the local primary care trust.

Conflict of interest:

none.

References:

Maniadakis N, Gray A.

The economic burden of back pain in the UK.

Pain 2000; 84: 95Ė103.Chew-Graham C, May C.

Chronic low back pain in general practice: the challenge of the consultation.

Fam Pract 1999; 16: 46Ė9.Parsons S, Harding G, Breen A et al.

The influence of patientsí and primary care practitionersí beliefs and expectations about chronic musculoskeletal pain on the process of care: a systematic review of qualitative studies.

Clin J Pain 2006; 23: 91Ė8.Foster NE, Pincus T, Underwood M, Vogel G, Harding S.

Understanding the process of care for chronic musculoskeletal painówhy a biomedical approach is inadequate.

Rheumatology 2003; 42: 401Ė3.Parsons S, Underwood M, Breen A et al.

Prevalence and comparative troublesomeness by age of musculoskeletal pain in different body locations.

Fam Pract 2007; 4: 308Ė16.Ritchie J, Lewis J.

Qualitative Research Practice: A Practical Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. 1st edn.

London: Sage, 2003.Harding G, Gantley M.

Qualitative methods: beyond the cookbook.

Fam Pract 1998; 15: 76Ė9.Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF.

Grading the severity of chronic pain.

Pain 1992; 50: 133Ė49.Kvale S.

Interviews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing, 2nd edn.

New York: Thousand Oaks, 1996.Egeli N, CrooksVAet al.

Patients views: improving care for people with fibromyalgia.

J Clin Nurs 2008; 17: 362Ė7.Alegretti A, Borkan J et al.

Paired interviews of shared experiences around chronic low back pain.

Fam Pract 2010; 27: 676Ė83.Bieber C, Muller KG et al.

Long term effects of a shared decisionmaking intervention on physician-patient interaction and outcome in fibromyalgia. A qualitative and quantitative one year follow up of a randomised controlled trial.

Patient Educ Couns 2006; 63: 357Ė66.Teh CE, Karp JF et al.

Older peopleís experiences of patient-centred treatment for chronic pain: a qualitative study.

Pain Med 2009; 10: 521Ė30.

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return to INTEGRATED HEALTH CARE

Since 1-16-2018

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |