Non-Surgical Interventions for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

Leading To Neurogenic Claudication:

A Clinical Practice GuidelineThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Pain 2021 (Sep); 22 (9): 1015–1039 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS André Bussières, Carolina Cancelliere, Carlo Ammendolia, Christine M Comer, Fadi Al Zoubi, Claude-Edouard Châtillon, Greg Chernish, James M Cox, Jordan A Gliedt, Danielle Haskett, Rikke Krüger Jensen, Andrée-Anne Marchand, et. al.

School of Physical Medicine & Occupational Therapy,

McGill University,

Montreal, Quebec, Canada;

Département Chiropratique,

Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières,

Quebec, Canada.

Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) causing neurogenic claudication (NC) is increasingly common with an aging population and can be associated with significant symptoms and functional limitations. We developed this guideline to present the evidence and provide clinical recommendations on nonsurgical management of patients with LSS causing NC. Using the GRADE approach, a multidisciplinary guidelines panel based recommendations on evidence from a systematic review of randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews published through June 2019, or expert consensus.

The literature monitored up to October 2020. Clinical outcomes evaluated included pain, disability, quality of life, and walking capacity. The target audience for this guideline includes all clinicians, and the target patient population includes adults with LSS (congenital and/or acquired, lateral recess or central canal, with or without low back pain, with or without spondylolisthesis) causing NC.

The guidelines panel developed 6 recommendations based on randomized controlled trials and 5 others based on professional consensus, summarized in 3 overarching recommendations: (Grade: statements are all conditional/weak recommendations)Recommendation 1. For patients with LSS causing NC, clinicians and patients may initially select multimodal care nonpharmacological therapies with education, advice and lifestyle changes, behavioral change techniques in conjunction with home exercise, manual therapy, and/or rehabilitation (moderate-quality evidence), traditional acupuncture on a trial basis (very low-quality evidence), and postoperative rehabilitation (supervised program of exercises and/or educational materials encouraging activity) with cognitive-behavioral therapy 12 weeks postsurgery (low-quality evidence).

Recommendation 2. In patients LSS causing NC, clinicians and patients may consider a trial of serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors or tricyclic antidepressants. (very low-quality evidence).

Recommendation 3. For patients LSS causing NC, we recommend against the use of the following pharmacological therapies: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, methylcobalamin, calcitonin, paracetamol, opioids, muscle relaxants, pregabalin (consensus-based), gabapentin (very low-quality), and epidural steroidal injections (high-quality evidence).

PERSPECTIVE: This guideline, on the basis of a systematic review of the evidence on the nonsurgical management of lumbar spine stenosis, provides recommendations developed by a multidisciplinary expert panel. Safe and effective non-surgical management of lumbar spine stenosis should be on the basis of a plan of care tailored to the individual and the type of treatment involved, and multimodal care is recommended in most situations.

There are more articles like this @ our new:

NON-PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY Page

Keywords: Practice guideline; disease management; lumbar spine stenosis; neurogenic claudication; nonsurgical treatment, rehabilitation.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Background

Spinal pain remains the leading cause of global disability. [17] Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS), a frequent cause of chronic low back and leg pain, is associated with significant disability and functional limitations. The mean prevalence estimates for LSS based on clinical or radiological diagnoses vary between 11% and 38% in the general population (mean age 62, age range 19–93), 15 to 25% in primary care and 29 to 32% in secondary care populations. [61] The prevalence and economic burden associated with LSS are expected to increase dramatically given the aging population. [30, 31, 123]

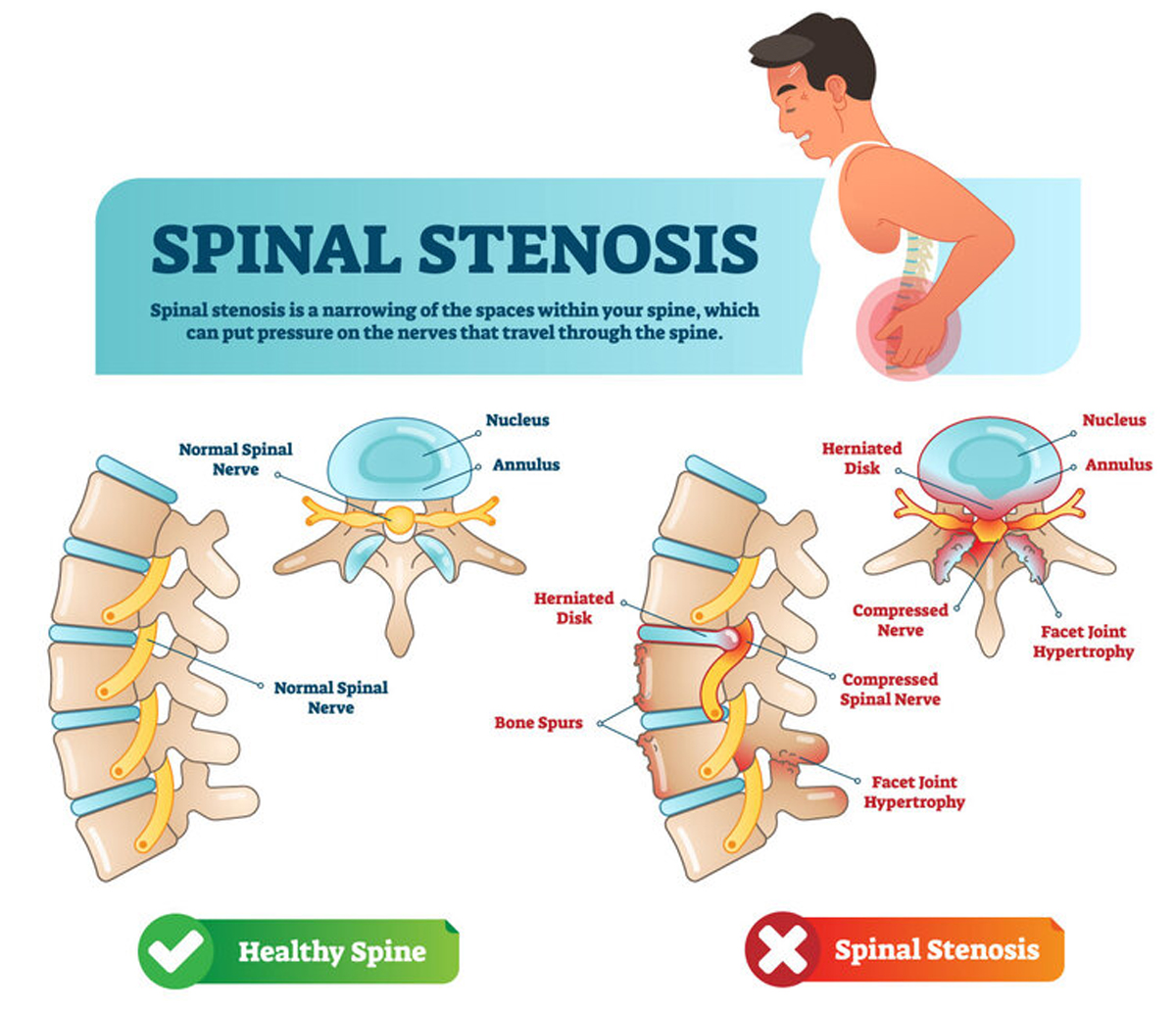

Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) is commonly a degenerative process causing the narrowing of the central spinal canal, lateral recesses, or intervertebral foramen (or a combination thereof), progressively compressing the neurovascular structures in the spinal canal or foramen. Lumbar spinal stenosis can be classified as acquired or congenital (developmental) or both and may be associated with degenerative spondylolisthesis or scoliosis. [10, 69, 75] Symptomatic LSS is typically described as neurogenic claudication (NC), characterized by unilateral or bilateral buttock, thigh or calf symptoms (aching, cramping, pain or sensory/balance problems with paresthesia, numbness and weakness) precipitated by prolonged standing or walking and relieved by sitting, lumbar flexion and lying down. [64, 122] Low back pain (LBP) may or may not be present with NC. [69] These symptomatic individuals report significant limited walking ability that impacts their capacity to engage in recreational and social activities, all leading to an important emotional impact on their lives. [4, 92, 96]

Diagnostic decisions require complex judgments that integrate advanced imaging and clinical findings along with knowledge of the patient's clinical course. [4, 30] Clinical classification criteria to identify patients with LSS causing NC include age over 60 years, positive 30-second extension test, negative straight leg test, pain in both legs, and leg pain relieved by sitting, leaning forward or flexing the spine. [44]

Although the natural history of mild to moderate degenerative LSS causing NC tends to be favorable in approximately 60% of patients (ie, improved or unchanged back or leg pain), [69, 85, 134] with approximately 30% of patients with LSS expected to worsen, [28] this condition remains the most common reason for spinal surgery in patients aged over 65 years. [31] While surgery may rapidly improve pain and disability over nonsurgical treatments in the first 3 months for some patients with LSS causing NC, [40, 78] the clinical benefits may not be sustained beyond 4 to 8 years. [58, 76] Reoperation rates at 8-year (18%) 63,78 have been reported. Some studies have demonstrated a larger proportion of adverse events in people undergoing surgical (10–24%) versus nonsurgical (0–3%) care. [78, 141] Lumbar spinal stenosis surgery is almost always an elective procedure. [75, 76] A referral for special investigations (eg, advanced imaging procedures, neurological and/or vascular investigations) and/or surgical consultation is recommended if the patient presents with severe intermittent claudication (walking #8804; 100 meters), new or progressive lower limb weakness, [127] and failure to respond to an appropriate/intensive course of nonsurgical care, as determined by the patient‘s quality of life and expectations.

The clinical management of LSS causing NC is challenging. The North American Spine Society (NASS) clinical practice guidelines [68] found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against the use of pharmacological or nonpharmacological treatments, while the Danish Health Authority (DHA) guideline [105] recommended against paracetamol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioids, neurogenic pain medication, muscle relaxants or manual therapy to treat these patients. The 2 guidelines currently available need to be updated because their recommendations were informed by evidence published more than 10 (NASS) [68] and 4 (DHA) [105] years ago respectively. Considering the substantial lack of high-quality evidence for the effectiveness of the interventions addressed in these guidelines, new trials are likely to impact the recommendations. Therefore, an updated, evidence-based clinical practice guideline is warranted to inform the nonsurgical management of LSS causing NC.

Discussion

We developed an evidence-based clinical practice guideline to help clinicians deliver effective interventions to individuals with LSS causing NC. Our recommendations, based on the best available evidence, expert opinion, and in consideration of patient values and preferences, intend to assist clinical decision making and promote healthcare system efficiency.

Our recommendations state which interventions should be offered; as well as those that should not be offered because their effectiveness has not been clearly established.

For patients with LSS causing NC, our recommendations are primarily based on low to moderate level evidence or consensus from a multidisciplinary working group. As such, the true treatment effect may differ from the estimated effects, therefore the results should be interpreted with caution.

Summary of Recommendations

Clinicians should work in partnership with patients to develop a patient-centered care plan that considers the patient's values and preferences, discussing with them effective intervention options, as well as risks and benefits of the care plan, and come up with a shared decision. We suggest clinicians consider offering a multimodal rehabilitation intervention consisting of a combination of education, sedentary and nutrition lifestyle modification for patients with limited walking ability and overweight or obese individuals with related comorbidities, behavioral change techniques in conjunction with manual therapy (spinal mobilization, manipulation, massage) of the thoracic and lumbar spine, pelvis, and lower extremities, and individually tailored supervised and home exercise program (stretches and strength training, cycling, and body weight-supported treadmill walking), a trial of acupuncture or antidepressants (SNRIs, TCAs), and, in cases where surgery was performed, postoperative rehabilitation with CBT. On the other hand, we cannot recommend the use of NSAIDs, analgesics (methylcobalamin, paracetamol, calcitonin), opioids as a first-line treatment, muscle relaxants, antiseizure neuropathic medication (pregabalin), or epidural steroidal injections.

All recommendations included in this guideline are based on very low to high risk of bias RCTs. Further, the overall quality of evidence ranged from very low to moderate considering other factors suggested by GRADE, such as imprecision and risks of bias, and thus the strength of recommendations is weak at this time. Nonetheless, given that the natural history of mild to moderate degenerative LSS tends to be favorable for about two-third of patients, [69, 85, 134] the inconclusive evidence about the moderate to long-term effectiveness of surgical interventions for people with LSS causing NC, [5, 28, 78, 105, 141] the higher risk of adverse events of surgical compared to nonsurgical interventions, [78, 141] and evidence that delaying surgery is not detrimental to surgical outcome, [143] a reasonable trial of multimodal rehabilitation intervention with or without selected medication is warranted for most symptomatic LSS patients prior to recommending more invasive interventions.

Comparisons With Other CPGs and Reviews on the Management of LSS

While our findings agreed with the DHA [105] and NASS [68, 69] guidelines regarding the common medications assessed, divergence in opinion with these 2 guidelines [68, 69, 105] can largely be explained by the use of different eligibility criteria, and the inclusion of recently published evidence on multimodal rehabilitation intervention [3, 86, 108] and acupuncture [103] upon which we were able to base our recommendations.

First, this guideline included a wider population of adults (≥18 years of age), is restricted to neurogenic claudication, and applies to a specific audience. Neurogenic claudication is due to neuroischemia where the radicular type is due to nerve root inflammation. The differing pathophysiology may require different treatment approaches. Further, only RCTs with an inception cohort of at least 30 participants per arm at baseline were admissible for non-normal distributions to approximate the normal distribution. [93] Importantly, three recent high to moderate quality RCTs [3, 86, 108] investigated the effectiveness of various combination of multimodal rehabilitation that have informed our guideline recommendations, but were not available when the NASS [68, 69] and DHA [105] guidelines were developed.

Second, the NASS guideline [68, 69] recommended a limited course of active physical therapy (education and exercise), while the DHA [105] recommended tailored supervised exercise as an option for patients with LSS . This guideline suggests clinicians consider offering a stepped-wise treatment approach with multimodal rehabilitation as first line treatment (and possibly acupuncture), alone or in combination with selected medication after considering potential risks and patient preference and values. Interestingly, the proposed sequential treatment approach parallels recommendations from recent guidelines on the management of adults with low back pain. [38, 102] Using the GRADE approach, the panel determined that the balance of desirable and undesirable outcomes favored multimodal rehabilitation consisting of manual therapy (spinal mobilization, manipulation, massage) of the thoracic and lumbar spine, pelvis, and lower extremities, and individually tailored supervised and home exercise program (stretches and strength training, cycling, and body weight-supported treadmill walking) combined with cognitive-behavioral therapy. All patients in Ammendolia (2018) [3] and Minetama (2019) [86] RCTs were allowed to continue with previously prescribed medications, while those in the trial by Schnieder (2019) [108] were randomly allocated to usual medical care, group exercise or manual therapy/individualized exercise. Results favored “intense” rehabilitation programs of care. A detailed description of the multimodal rehabilitation program is available elsewhere. [2]

Third, the NASS guideline [68, 69] found insufficient evidence to support the use of acupuncture while the DHA guideline [105] did not assess this modality. While this guideline suggest acupuncture may be recommended if patients have a preference for or willingness to receive acupuncture, this is based on very low quality evidence from small RCTs showing borderline clinically important short-term improvement and is insufficient to suggest long-term benefit. Whether the results from the trials conducted in Asia would generalize to another or larger LSS population remains to be determined. [2]

Lastly, this guideline recommend against the use of NSAIDs, methylcobalamin, paracetamol, calcitonin, opioids, muscle relaxants, pregabalin, or gabapentin. As patients with LSS often present with LBP, clinicians may want to considered a review of systematic reviews by Wong et al (2016) [137] concluding that oral NSAIDs are more effective than placebo for nonspecific chronic LBP, but not for acute LBP. Guidelines generally advise prescribing oral NSAIDs at the lowest effective dose for the shortest time possible. Any potential benefits should be weighed against the risk of harm. [80] A Cochrane review by Saragiotto et al (2016) [106] concluded that Paracetamol does not produce better outcomes than placebo for people with acute LBP, and it is uncertain if it has any effect on chronic LBP.

Based on consensus, this guideline and the DHA guideline [105] suggest that opioids should only be used for patients with LSS who have failed to respond to the aforementioned treatments, and only if the potential benefits outweigh the risks for individual patients. Shared decision making should include a discussion of known risks and realistic benefits with these patients. [19, 33, 75, 82] The American College of Physician (ACP) guidelines for LBP including radiculopathy recommended against the use of opioids as a first or second line treatment. [102] Based on indirect evidence, [24, 129] we recommend against the routine use of skeletal muscle relaxants in patients with LSS considering the risks of transient adverse effects. The DHA [105] state in their guideline "It is good practice to avoid use of muscle relaxants in these patients, since the beneficial effect is uncertain and there is a risk of adverse reactions, including dizziness, fatigue, dry mouth, muscle weakness and gastrointestinal effects, may outweigh the unknown potential benefit of muscle relaxants." The ACP guideline [102] recommended skeletal muscle relaxants as a second line treatment for acute and subacute LBP if pharmacologic therapy is desired.

We also recommended against the use of epidural steroid injections (ESI) for patients with LSS and NC. While ESI was not covered in DHA guideline, [105] the NASS [68, 68] guideline recommended interlaminar ESI for short-term (2 weeks to 6 months) symptom relief in patients with NC or radiculopathy. There is, however, conflicting evidence concerning long-term (21–24 months) effectiveness. The difference between our recommendation for ESI and the NASS guideline [68, 69] can be explained by the fact that the NASS inclusion criteria allowed for inclusion of studies of patients with lumbosacral radicular pain, in addition to those with LSS and NC. [72] In contrast, our inclusion criteria required that patients in the study were diagnosed specifically with LSS and NC.

Function and Participation

Symptomatic LSS strongly impacts individuals’ emotional state, quality of life, and physical function including walking, recreational activities such as sports and exercise, standing, social activities, household activities, managing comorbid health conditions, working, sleeping and lifting. [4, 77, 96] Thus, health care providers should be prepared to address negative emotional responses to LSS and related misconceptions, and provide advice and education about LSS, including individualized care based on self-management techniques and lifestyle changes. [77] Sedentary and nutrition lifestyle modification for patients with limited walking ability and overweight or obese individuals with related comorbidities may include low-cost wearable accelerometer or pedometer-based physical activity promotion, nutrition education by a dietician, and advice from an exercise physiologist over a 12-week intervention. [71, 120, 125] In a pilot trial, participants logged on to the e-health Web site to access personal step goals, nutrition education videos, and a discussion board. [125]

Despite the benefits of physical activity for reducing the risk of chronic health conditions, only 32% of clinicians advise older adult patients to begin or continue to do exercise or physical activity during office visits. [12] Clinicians’ reluctance to prescribe physical activity to older patients may be attributable to a lack of knowledge regarding appropriate exercise prescription for older adults in light of the potential risks and benefits of various doses and types of exercise. [142] Barriers to exercise participation among older adults include fear of pain or exacerbation of existing pain, low self-efficacy, fear of injury, lack of social support, and social isolation. [29, 142] Perhaps as a result, patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain prefer individually tailored information and support when prescribed physical activity. [63] Interventions that combine both behavioral and cognitive behavior change techniques are more effective than interventions that only use one for older adults. [11] Frameworks and guidelines for exercise prescription in older adults and modification of these guidelines for patients with the most common age-associated comorbidities are available to assist clinicians. [11, 142] Pre-exercise screening prior to initiating an exercise program is recommended, along with considerations to modify medications if necessary.

Dissemination and Implementation Plan

While the potential resource implications (specialized staff, cost) of applying the guideline recommendations are considered small, a recent manual by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) can be used to assess the financial change in the use of resources (cost or saving) as a result of implementing this guideline. [89]

Once a decision to disseminate and/or implement this guideline has been made to help improve the management of patients with LSS leading to NC, the following 6 steps of the Knowledge-to-Action framework may be considered: [46]

Adapting knowledge to local context: Clinicians, insurers and policymakers should consider using the ADAPTE framework to adapt this guideline to their needs and jurisdictions. [26] Resource-constrained settings may prefer using alternative approaches described elsewhere. [83]

Assessing barriers/enablers to knowledge use: Uptake of guideline recommendations in clinical practice can be impeded by a wide range of professional (eg lack of time, knowledge, skills, self-capacity, misperceptions about evidence-based CPGs,) [20, 51, 116] and organizational/environmental barriers (eg leadership, organizational culture, years involved in quality improvement, data infrastructure/information systems, and resources). [52] Stakeholders and researchers may use the recently developed Clinician Guideline Determinants Questionnaire, a validated tool that addresses multiple potential determinants specific to guideline use from a clinician perspective. [41]

Selecting, tailoring, implementing interventions: Knowledge Translation (KT) strategies to increase the likelihood of successful guideline uptake and reduce knowledge-practice gaps should aim to target problem behaviors of care providers, [1, 13, 95, 110] patients, [43, 107] and wider health care organizations. [53] Numerous theories, models, and frameworks can be used to inform each step of the KT process (planning/design, dissemination and implementation, evaluation, and sustainability) or across the full KT spectrum (from planning to sustainability). [91, 121] The Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) taxonomy propose a systematic approach to specifying active components of implementation strategies when planning small- and large-scale implementation efforts. [99, 101] Depending on the specific barriers to uptake and available resources, interventions can range from low cost manually-generated reminders delivered to providers on paper, [97] audit and feedback, [60] and use of local opinion leaders. [37] Ongoing and frequent theory-based implementation interventions are recommended to effectively change clinical practice and improve patient health. [84, 26] As with prior guidelines, [21, 22] we considered the Guideline Implementation Planning Checklist [42] and available strategies and supporting evidence to increase guideline uptake. [36] To raise awareness, professional organizations are encouraged to inform their members of this new guideline and companion documents for practitioners (Appendix 11) and patients (Appendix 12) easily accessible at: https://www.ccgi-research.com/ and http://boneandjointcanada.com/ to help with “front line” dissemination.

Monitoring the use of the guideline, 5) evaluating its impact, and 6) assessing sustained use: These steps may be done through surveys, chart reviews or electronic health records, and intervention studies to evaluate impact. [60] For instance, the Clinician Guideline Determinants Questionnaire [41] can be used at multiple time points to assess determinants of the use of our new guideline, before and after implementation of an intervention to demonstrate impact on guideline use or following audit showing failure to routinely apply guideline recommendations to plan interventions to sustain guideline use. Identifying indicators of success should be defined a priori (eg, outcomes related to clinician learning and performance, patient outcomes and cost-effectiveness of care).

Research Implications

Future research should aim to identify and validate LSS clinical phenotypes (NC pain symptoms; NC claudication sensory /balance symptoms; NC radicular unilateral leg pain) and associated severity of symptoms/disability (ie, mild, moderate, severe) in relationship to the severity of structural anatomical changes that may more likely be predictive of those patients who may to benefit from conservative versus surgical treatment approaches. Research should also prioritize high quality RCTs testing various combinations of modalities of nonpharmacological (eg, education about self-care, home vs supervised exercise, manual therapy, acupuncture, CBT and other psychological interventions, perioperative rehabilitation) and pharmacological treatments (eg, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants) and dosage (duration and intensities) required for optimal benefits for each phenotype, while considering patient preference, [4, 16, 67, 77] and determining the most important (objective) outcomes that are meaningful to patients to gauge treatment success aligned with patients’ goals (eg, participating in recreational and social activities). [81] The completion of RCTs comparing best medical management with or without antidepressants (SNRIs or TCAs) in patients with symptomatic LSS is also encouraged. Ongoing trials may provide partial answers. [7, 124, 135]

Guidelines Update

Methods for updating these guidelines are as reported in our prior guidelines [21] and others. [90, 114] The Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative will follow the following process: (1) monitoring changes in evidence, available interventions, importance and value of outcomes, resources available, and relevance of the recommendations to clinicians (limited systematic literature searches each year for 3-5 years and survey to experts in the field annually); (2) assessing the need to full or partial update (relevance of the new evidence or other changes, type and scope of the update); and (3) communicating the process, resources, and timeline to the Guideline Advisory Committee of the CCGI, who will submit a recommendation to the Guideline Steering Committee to make a decision to update and schedule the process. Further, a recently developed checklist (CheckUp) will be used to improve the reporting of the updated guideline. [131]

Strengths and Limitations

This clinical practice guideline was based on comprehensive literature search and updated the evidence from 2 previous guidelines. We used the GRADE approach providing clear link between recommendations and evidence. This guideline was peer-reviewed by international experts who provided detailed comments prior to release of the final report. Nonetheless, our guideline also has limitations.

First, given that we were also interested in pharmacological interventions, we may have missed studies published in Embase related to the effectiveness of pharmacological therapies in individuals with LSS causing NC.

Second, we only searched for articles published in English.

Third, only 2 databases (MEDLINE and Cochrane Central) were searched in our updated search (January 2014 through June 2019). However, the 3-year search overlap (2014-2017) between the initial and updated search did not uncover any new admissible articles, and 4 coauthors (CA, JO, KS, AB) involved in a parallel Cochrane review using several additional databases identified only 2 additional admissible RCT86,103 which were incorporated in this guideline.

Forth, although the composition of the guideline panel was diverse, with experienced methodologists, expert clinicians and surgeons, stakeholder and patient representatives, a majority of the panel members had clinical training in chiropractic. When updating this guideline, the future panel should include a larger proportion of GPs, rheumatologists, physiatrists, experts in pain and interventional radiology, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, massage therapists, and naturopaths. Expanding the multidisciplinary nature of a future panel will ensure a broader forum for discussion among panelists. Additional efforts should be made to include participants from South America, Asia and Africa.

Fifth, patient experiences or expectations were mainly informed by recent qualitative studies. [16, 77];

Sixth, the scope of this guideline focused on selected outcomes such as pain, disability and function although included studies assessed additional patient outcomes. In addition, poor descriptions of the interventions evaluated by included studies were common;

Seventh, our recommendations were limited by the amount and quality of evidence published in the literature. The low quality of evidence mainly related to the randomization process, and deviations from the intended interventions in RCTs; blinding, incomplete outcome data, and selective outcome reporting in observational studies. Therefore, new high-quality trials are likely to impact the recommendations in future guidelines.8

Given the limited number of RCTs addressing LSS patients matching our inclusion criteria, studies did not always explicitly fit our inclusion criteria. Any differences in LSS patient population were accounted for in both the wording of the recommendation/remarks, and the full description of the evidence precluding to support the recommendation/remark statement.

Guideline Disclaimer

The evidence-based practice guidelines published by the Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative (CCGI) in collaboration with Bone and Joint Canada include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options. Guidelines are intended to inform clinical decision making, are not prescriptive in nature, and do not replace professional care or advice, which always should be sought for any specific condition. Furthermore, guidelines may not be complete or accurate because new studies that have been published too late in the process of guideline development or after publication are not incorporated into any particular guideline before it is disseminated. CCGI and its working group members, executive committee, and stakeholders (the “CCGI Parties”) disclaim all liability for the accuracy or completeness of a guideline and disclaim all warranties, expressed or implied. Guideline users are urged to seek out newer information that might impact the diagnostic and/or treatment recommendations contained within a guideline. The CCGI Parties further disclaim all liability for any damages whatsoever (including, without limitation, direct, indirect, incidental, punitive, or consequential damages) arising out of the use, inability to use, or the results of use of a guideline, any references used in a guideline, or the materials, information, or procedures contained in a guideline, based on any legal theory whatsoever and whether or not there was advice of the possibility of such damages.

Through a comprehensive and systematic literature review, CCGI evidence-based clinical practice guidelines incorporate data from the existing peer-reviewed literature. This literature meets the pre specified inclusion criteria for the clinical research question, which CCGI considers, at the time of publication, to be the best evidence available for general clinical information purposes. This evidence is of varying quality from original studies of varying methodological rigor. CCGI recommends that performance measures for quality improvement, performance-based reimbursement, and public reporting purposes should be based on rigorously developed guideline recommendations.

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return NON-PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Since 6-22-2021

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |