Principles in Integrative Chiropractic This section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003 (May); 26 (4): 254–272 ~ FULL TEXT

J.Michael Menke, DC

Program in Internal Medicine,

University of Arizona,

Tucson 85719, USA.

jmmenke@aol.com

Introduction

As the public acceptance of chiropractic continues to grow in the United States, [1–3] the private practice chiropractor may find opportunities for formal inclusion in the fast growing integration of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) into health care delivery. The ability of chiropractors to respond confidently to integration into the overall health care system may be the next step in gaining access to more patients and improving the health care quality.

This necessity for chiropractors to become part of the evolving health care system and still maintain a strong chiropractic identity will be essential, since chiropractic’s value lies in cultivating and delivering the very elements that have made it so high in patient satisfaction: emphasis on biomechanics, manual therapy of the spine, good patient rapport, and strong patient-physician bond. [4, 5] However, there are several barriers to integration: consumer, medical, and chiropractic itself.

There are more articles like this @ our:

Integrated Health Care and Chiropractic PageConsumer concerns are related to issues of safety and possible side effects, a perceived lack of science, and the public’s reliance on medical physicians for primary advice on health and chiropractic. [6] Medical physicians are also concerned about the lack of science, competitive roles between themselves and the chiropractor, malpractice issues, and quality of care. [2, 7] Medical groups are more concerned with the business issues of economics and cost benefit [8] in incorporating chiropractic. Chiropractors are more likely concerned about losing autonomy and professional status and create barriers through their interprofessional communication.

Integration of all complementary and alternative medicines, including chiropractic, is now occurring in hospitals and medical groups throughout the United States. [9, 10] Medicine is becoming proactive on the issue and offering courses in medical schools on CAM, which include information on chiropractic. [11, 12] Some medical physicians have expressed interest in learning chiropractic technique, [13] although there is evidence that incorporating spinal manipulation into medical practice would more than double patient contact time, [14] is inconsistent in quality of application, and yields equivocal results. [15] Indeed, in the United Kingdom, 20% of general medical practices already include a complementary therapy, primarily chiropractic, osteopathy, and acupuncture. [16] In the United States, hospital-based CAM programs increased by 33% between 1998 and 1999. [6] Chiropractic is among the top 3 CAMs because of patient popularity, income, and potential health care savings. [6, 17]

Health service journals and consultants are encouraging their hospital and medical group clients to enter this fast growing and potentially lucrative segment of the health care market. [9, 10] Unless chiropractors become proactive in creating their place in an integrated system; however, they could find themselves assigned to limited roles within this new system, akin to physical therapy. Alternatively, chiropractors could prepare themselves to take advantage of integration as an opportunity to benefit their patients and their professional growth. [18] In the first scenario, chiropractic’s destiny is left to managed care and medicine; in the second, destiny is in the hands of chiropractors.

Recent surveys show only 1.8% of medical doctors are unfamiliar with chiropractic. [19] Seventy-seven percent of medical doctors find chiropractic to be beneficial for their patients, and 83% believe spinal manipulation has benefit for certain conditions. [20] Other studies show as many as 90% of medical physicians accept chiropractic as a legitimate health care profession [13, 21] and as offering a useful treatment. [20, 22] Chiropractic services are especially accepted among younger medical physicians with primary care responsibilities. [22] Medical physicians consider chiropractic among the most effective of all the CAM therapies. [5] A whole new generation of medical doctors has curiosity and openness to chiropractic, perhaps piqued by a course on alternative medicine taken in medical school, [11, 12] the buzz of consumer utilization, [1, 23, 24] or a personal or family member’s experience. [19] In addition, studies suggest that spinal manipulation is a successful treatment strategy for some of the musculoskeletal conditions that frequent primary care practice. [17]

Chiropractic as a health care solution?

The health care system is straining to meet the demand for conservative, safe, and effective care and employers’ needs for comprehensive or minimum employee benefits. US health care costs outpaced the 6.5% growth of the economy as a whole in the year 2000. Not adjusting for inflation, health care was 12% of the gross domestic product in 1990, 13.1% in 1999, and 13.2% in 2000. [25, 26] US expenditures for individual health care costs were $2,966 in 1991, $4,001 in 1997, $4,377 in 1999, and $4,637 in 2000. Overall, national health spending rose $83.9 billion in 2000, with 45% of the increase due to hospitalization (which rose 5.1%) and prescription drugs (which rose 17.3%). By 2000, drug spending had experienced 6 years of double-digit growth. [26] In 2000, private health insurance premiums increased 8.4%. [26]

As an illustration of how chiropractic services may reduce health care costs, the comparison of chiropractic services to back surgeries is useful. A recent nationwide survey of direct costs of laminectomies and fusions range from about $60,000 for a cervical laminectomy ($112,000 for a fusion) and $83,000 for a lumbar laminectomy ($169,000 for a lumbar fusion). [27] What impact might an integrated course of chiropractic treatment prior to surgery have on the $50 billion total spent on direct costs for back pain [4] and the additional $50 billion for indirect costs? [28, 29] Manipulation is no substitute for all back surgeries but as Deyo [30] has indicated, countries with the most back surgeries are countries with the most back surgeons, with the obvious implication that there are probably many unneeded back surgeries and too many unnecessary expensive diagnostic tests.

Chiropractors treat common maladies from a unique conceptual framework, an approach low in risk and highly popular with a tremendous potential for savings. [1, 23, 24] More than simply offering a conservative treatment strategy, chiropractors usually offer guidance related to life-style choices, such as exercise and nutrition, [31–33] which can also reduce the need for acute and chronic medical care.

Almost all chiropractic patients have a medical doctor, and chiropractors see, if not treat, the same conditions seen by medical physicians. [34] Thus, chiropractors directly and indirectly impact the most common cases seen in medical primary care offices. [30] People like their medical physician and are unwilling to consider medicine as an option. [23, 34]

The inclusion of chiropractors into medical groups and hospitals is seen as inevitable by some for reasons of profitability, possibly lowering cost burdens, and high patient demand. [4, 9, 17, 35] At least one author even suggests that CAMs have a cost-benefit advantage over orthodox medicine for some conditions. [17] Undoubtedly, chiropractors will increasingly participate in integrated and integrative health care and must learn about the complex systems in which they will find themselves. For chiropractors, a deeper knowledge of medical practices, procedures, and protocols will be required to meet this demand. This will only enhance acceptance and professional stature as health resources in their communities.

In turn, the chiropractic profession has much to offer an integrated multidisciplinary medical environment because of its hands-on approach, growing popularity with the public, low risk of side effects, life-style contextual emphasis, conservative intervention, emerging scientific support, and safety and efficacy. [4, 36, 37, 38] But chiropractors will need to enter the integrated arena with the extra skills and knowledge of how the health care system and its practitioners work to minimize confusion and to maximize the professional contribution. The future role of chiropractic and delivery of services should be defined clearly within the integrated context and emphasize patient management (evaluation and care planning), as well as care oversight and coordination when appropriate. Otherwise, there exists a risk of being perceived simply as a specialty provider or allied assisting professional. Consideration as a substitute for physical therapy or role confusion as a limited musculoskeletal subspecialty might also be default niches chiropractors could be perceived as filling in an integrated system.

Table 1 Not all chiropractors need be fully integrated into health care, but there should be room for integrative ones within the chiropractic profession and training available so they will not get lost in a system that would prefer to fit them into a conceptual box within the medical paradigm. They will need to identify and keep their professional “center of gravity.” They will learn how to deliver their contribution in a system overdue for innovation, on the cusp of reform, but highly resistant to change. Table 1 identifies key areas that should be considered for participation in integrated settings.

Chiropractic services integrated into a medical delivery system can be referred to as integrative chiropractic and chiropractors working closely with or within medical environments named integrative chiropractors. Integrative chiropractors will need to learn how to work with and/or within the larger health care delivery system and have a working knowledge of all stakeholders involved, including physicians, medical groups, hospitals, the extended community, and patients.

Trends in demand for chiropractic

The use of CAMs and chiropractic services has increased dramatically in the past decade. First came the revelation that chiropractors were well utilized, as revealed by survey data collected in 1990 by David Eisenberg et al of Harvard. [2] Ten percent of the public visited a chiropractor in 1990. Seventy-one percent of chiropractic patients received treatment that year, with an average of 904. [8] chiropractic visits per 1000 US population. In 1997, chiropractic utilization had risen 0.9%, from 10.1% to 11%; 90% of chiropractic patients saw their chiropractor; and the utilization rate rose to 969.1 visits per 1000 US population. Total chiropractic visits for 1997 were 191,886,000.

In 1998, John Astin’s [24] study estimated chiropractic utilization at 15.7%. The next most utilized alternative treatments were life-style–diet changes (8%), exercise/movement (7.2%), and relaxation training (6.9%). Note that life-style, exercise, and relaxation training did not require practitioners but were self-care interventions. In 2000, a web-based study (with obvious selection bias, as respondents had online access) found that 37% of respondents had tried chiropractic, based on a sample size of 1,148 adults who used the Internet. [9] By contrast, a recent survey of 3.7 million residents in the Atlanta metropolitan area, home to the largest chiropractic training institution, revealed that only 5% of health care subscribers used CAM therapies, only 30,000 of whom were consumers of chiropractic services. [39] Overall, CAM consumers mostly sought treatment for back problems, arthritis and rheumatism, headaches, and sprains and strains. Chiropractors are a major provider of low back pain treatment, since 1 in 3 patients with low back pain seek chiropractic care. [3, 40]

Eighty-three percent of companies with greater than 500 employees offer chiropractic coverage. [41] Stanger and Coughlan [42] point out that employees seek alternative solutions for problems for which medicine has not been particularly effective, including chronic pain and chronic low back pain, hypertension, diabetes, depression, and asthma. As a result, employee benefit programs have included chiropractic services, as reflected in the increases in insurance coverage of chiropractic users and adoption by carriers of chiropractic coverage. [1, 8] Consumer demand is the preeminent force for chiropractic and all CAM benefits. [8] Chiropractic is often included in integrated CAM offerings, given that it is the most popular CAM practice and is seen by some experts as one of the most cost-effective therapies. [17]

Eleven percent of hospitals in 1998 initiated CAM enterprises in response to consumer demand with clear urging from trade publications, [10] representing a 33% increase in one year. Even at a more modest growth of just 5% per year, in 5 to 7 years, 45% to 50% of hospitals will offer CAM services. [43, 44] A study by VHA Inc. established that 10.2% of all hospitals and 11.2% of community hospitals offered some type of CAM in 1999. [9] One community hospital in the US northeast projected $90,000 to $350,000 in additional net revenue from its integrated medicine program within 3 years. Chiropractic is included in this particular integrated CAM offering. [9]

The most common obstacles to integration of a CAM into the mainstream health care delivery system are lack of research, economics, ignorance about the CAM, provider competition, and lack of practice standards. [7, 8, 13, 19, 21, 44] Largely, chiropractic is included in this particular integrated CAM offering. [9]

Defining integrative medicine

As defined by Rees and Weil, [11] “integrated medicine (or integrative medicine as it is referred to in the United States) is practicing medicine in a way that selectively incorporates elements of complementary and alternative medicine into comprehensive treatment plans alongside solidly orthodox methods of diagnosis and treatment.” This statement expresses the progressive medical viewpoint that orthodox medicine needs to be solidly included in the integrative medicine delivery model. Chiropractic may be integrated as a complementary approach or assume a role alternative to medicine and medical delivery. Issues remain as to how such disparate systems will be integrated, as a gate-kept therapy via primary care physicians, closer co-management, or through referral. Ultimately, implicit in integrative medicine delivery is the hope and intent for better outcomes at lower cost.

In the United States in the recent past, integrated health care delivery models meant health systems designed to deliver better medical care and lower costs through shared medical resources and improved economies of scale. This model only included “orthodox” medicine, specialties, and allied health professionals, such as nurses, advanced care nurses, physician assistants, and physical therapists but not complementary and alternative therapies. With the publication of the recent utilization and clinical outcome research on alternative therapies, [6] integrative medicine could improve delivery and clinical outcomes while saving health care costs. McGrady [44] points out that CAM is a potentially effective disease management strategy, that consumers utilize it, and it may therefore be an important component for success of any integrated delivery system.

Enterprising solo providers may use integrative medicine as a synonym for alternative and complementary medicine. This stretches the term beyond its intended meaning, since integrative must include biomedical procedures and tests. Thus, integrative solo practitioners of all kinds (acupuncturists, chiropractors, etc.) need to be affiliated with biomedical providers and interventions to designate themselves as integrative. Integrative chiropractic care delivery would thus be provided in conjunction with medical specialties in some fashion as part of a total community health care delivery system. This would provide easy and seamless patient referrals between providers, communication with a common language, and well-coordinated medical records transfer. [45] With the increasing scientific knowledge base, no single provider offers the full breadth of care possibilities without being a part of an extended family of health care.

Integrating chiropractic services into health care can occur under several scenarios. Up to now, integration between medical and chiropractic physicians has been the responsibility of consumers. Survey estimates show medical physicians who referred patients to chiropractors in the previous week range from 12.6% to 18%. [4, 16] American physicians who claim to have referred at least 1 patient to a chiropractor are estimated to be as high as 60%, [7, 8, 20] though 90% of chiropractic patients are self-referred. [46] This implies referrals from medical doctors are relatively rare; those reporting to have referred a patient may have referred only once.

Even at the patient-initiated level of integration, chiropractors and medical physicians can and do communicate somewhat about patient status and concerns, each from his or her own clinical point of view. Interprofessional communication, even with referral, has been too rare and lacking in quality. [7, 43, 47] Degrees of interprofessional integration may range from parallel to coordinated practice models. [48] In a parallel practices model, practitioners may or may not share a facility while referring patients and records to each other and thus may or may not provide a single location for consumers.

An example of integrated parallel practice is the sole proprietor chiropractic practice that sends and receives patients and accompanying patient information to and from primary care medical physicians in a local medical group or hospital. In most cases, it will be the chiropractor’s responsibility for initiating a parallel practice integrative network, given that medical institutions have little exposure to chiropractic and therefore do not perceive a need.

At the other end of the spectrum, in a true coordinated practice, practitioners do more than share information. They consult in a formal manner, such as patient conferences, to discuss successful treatments as well as to discuss complicated or intractable cases. The truly coordinated integrative chiropractic practice may be a staff position in a medical facility. In this case, the chiropractor may be subject to institutional review, case management, and quality assurance just like other providers in the facility.

Integrative chiropractic senior principles

At all levels of integrative health care delivery, from parallel to coordinated, there are several key principles: continuum of care, coordinated care, patient-centered care, best medicine or standards of care, and evidence-based medicine.

In the course of integration, chiropractors should not be intimidated into abandoning their unique contribution to health care delivery by becoming musculoskeletal specialists. Therefore, in addition to learning new communication skills within the integrative milieu, chiropractors must be equipped to express in the common language and expectations of medicine, especially with respect to diagnosis and evidence. Each dimension requires the integrative chiropractor to see where he or she will fit into the evolving health care paradigm, into which everyone else is also seeking their own evolving role. Integrative chiropractors will share the bigger concerns of health care—beyond those of chiropractic treatment, profession, or business. “How can the public’s needs best be met with my role as a chiropractor in a hospital emergency department or physical medicine?” should be the question asked, and it will need to be answered with evidence and the greater public good in mind.

Continuum of care

Continuity or continuum of care is defined as “a client-oriented system composed of both services and integrating mechanisms that guide and track patients over time through a comprehensive array of health, mental health, and social services spanning all levels of intensity of care.” [45] It is further described as a seamless approach wherein transfer of records and patient care to other providers is easy and efficient and does not cause major effort or concern on the part of the patient. In this dimension, the chiropractor’s role in health care will be included in the fabric of what is best for the community, the environment, and individuals, in addition to local medical groups and hospitals. In an integrated medical group, cases that are most appropriate for chiropractors should be referred to chiropractors. This delivery structure could benefit from chiropractors as “first contact” for treatment and triage. Standards for care (see below) and outcomes (evidence-based, also below) will evolve and grow over the course of treating many patients by integrated chiropractic-medical care protocols and algorithms.

Chiropractic continuum of care demands regular and periodic communication with medical physicians; keeping track of patients’ progress under another physician’s care, patient’s service reimbursement plans, and services provided; and referring patients appropriately and quickly for the next best intervention. A place in the health care continuum must involve a greater role in triaging patients and acting as a resource for health information and health care providers. For example, chiropractors may identify and interview medical physicians that still have “open” practices in geriatrics, internal medicine, pediatrics, or family practice. Often, it is helpful to a patient to match the personality of the provider as much as the specialty need. And which physician works well with chiropractors? Emergencies are often better served by a team approach. The chiropractor calling the orthopedist on the patient’s behalf to facilitate an evaluation enhances patient satisfaction, creates an alliance with the orthopedist, and reflects well on the chiropractor seeking to find the quickest and best solution to the patient’s problem.

Best practices or standards of care

One aspect of a care continuum is that patients should be offered the best treatment for their condition as it exists at the time. Best treatment could be described as that which has the lowest risk and highest efficacy. Best practices may be formalized through consensus as treatment guidelines. Though chiropractors have their own in the form of the Mercy Guidelines, [49] an integrative version will be needed. Integrative guidelines set parameters for what a medical group or hospital can expect from an affiliated or staff chiropractor and chiropractic treatment. Since the medical world has standards of care for many diagnosed conditions, integrative chiropractors will experience the same expectation.

Figure 1

Figure 2 Ultimately, such integrative standards of care have the potential to improve health care itself. For example, a rational integrative standard of care for back pain care may include a trial of chiropractic management initially, perhaps followed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) if the response to care is unsatisfactory, and least invasive surgical intervention for the diagnosis. Conservative spine care by chiropractic management could be one of the first integrative treatment options instead of, or along with, rest and a primary care prescription for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications. [27] Figute 1, Figure 2 (see Appendix) suggest an integrated approach to low back pain in a primary care environment.

Coordinated care

One of the advantages to interdisciplinary care for patients is that care can be coordinated; providers work together or, at the very least, are in communication about the various aspects of the patient’s health and needs. In patient choice and third party reimbursement, chiropractic is already integrated to a degree. In the sense of interdisciplinary coordinated care with conventional medical doctors, chiropractic is only rarely fully integrated. [4] Levels of coordinated care will range from basic referrals accompanied by communication to case conference format with coordinated management. [48]

Patient-centered care

The importance of focusing on the patient more than the procedure is a current topic in health care. Conditions are to be considered in the context of the whole patient, the biopsychosocial aspect. [50] Patient-centered care is more than just spending time with patients and relating to them in a more personal way. Patient-centered care can also be a principle by which treatment protocols are designed to maximize clinical outcomes. As an example, a 300–pound patient with disk herniation receives chiropractic treatment for a reasonable amount of time without success. Before referring the patient out for a medical consult, an integrative chiropractor would discuss risks and benefits of procedures, including extended chiropractic care, review the options with the patient, and then refer and discuss the next steps directly with a medical physician. The patient is not seen as lost to a competitor or competitive thought system but rather as having received the best care available. After surgery, the patient could return for chiropractic management and rehabilitation. This renders patient-centered care at its best.

Evidence-based care

David Grimes, [51] in his simple but eloquent article on evidence-based medicine, called for medical care to be based on evidence, rather than merely on authorities, experts, habits, and customs. He pointed out that traditional medical practice relies on assumptions almost 4 centuries old: older physicians are experts, physiology provides scientific foundation for competence, clinical experience equips one to evaluate health care innovations, and clinical mastery enables doctors to formulate their own practice guidelines.

The evidence-based paradigm has different assumptions. Outcomes, not experts, provide evidence of care effectiveness, and a formal method is followed to evaluate evidence of best practices. [51] Dr. Grimes warns of the trap of unexamined dogma: adopting technology without evidence of its effectiveness. The chiropractor will recognize echoes of these concerns within the chiropractic profession. For integrative chiropractors, the same evidence-based questions will be asked that medical physicians are asking of themselves: What intervention works and what does not? And where do you get your information?

For medical physicians, the hierarchy of evidence from most to least compelling is as follows: prospective randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs), physiologic mechanisms; retrospective studies; personal experience; recommendation of another specialist to whom they have referred a patient, with case reports; recommendation by respected colleagues; recommendation of family and friends; and case reports in alternative medicine journals. [19] Often without tools for evaluating techniques, chiropractors too often rely only on word-of-mouth, testimony, or expert opinion in evaluating a new technique.

The issue of evidence-based care inevitably arises in conversations with interested medical physicians. They want to know of research that supports chiropractic safety and treatment efficacy. They may also want to assess a chiropractor’s depth of knowledge of such literature. It is interesting that randomized controlled clinical trials are the highest standard for research, but medical physicians accept reasonable physiologic models, especially when RCTs are unavailable. Surprisingly, personal experience ranks highly in evaluating the efficacy of an unknown treatment, above professional recommendations and even case reports. [19]

The need for integration

Patient benefit

Patient-centered care is a higher ethical concern than professional chauvinism. If guided by the patient-centered “compass,” difficult questions are often easily resolved. What is best for the patient guides the treatment. When treated by conservative means first, with advice on life-style and self-care, reduced side effects from surgery, and better outcomes as possibilities, patients can only benefit. Patient satisfaction with chiropractors has always been very good, regardless of other outcomes [15], and would expect to continue or improve in the integrative context. Seriously ill patients who see CAM providers are reluctant to inform their medical providers. [14] In a true openly integrated health care environment, patients are free to openly speak of their treatment with chiropractors and with medical physicians and thus facilitate interprofessional communication and coordinate care.

Benefit to health care delivery

Integrative medicine that includes chiropractic holds greater promise of improving health outcomes by treating or managing some difficult and chronic conditions. A competent chiropractor enriches the resources at the disposal of primary care delivery. Cases treated by chiropractors can be co-treated with pharmaceutical prescriptions to enhance recovery, if indicated. Integrative chiropractors are trained in and already predisposed to reinforce life-style and medical compliance with respect to coronary artery disease and high blood pressure, diabetes, depression, and asthma. Chiropractors serving as physician “extenders” appeals to medical physicians by releasing physicians to do what they do best (eg, crisis care) and should be attractive to medical systems by saving money. [52]

Indeed, the chiropractors’ greatest contribution to integrative health care delivery may lie in reinforcing healthier life-style practices and identifying possible treatment interactions between herbs, prescriptions, or over-the-counter pharmaceuticals that many patients are taking without professional guidance. And truly integrated chiropractors would consult with the medical physician as to evidence-based alternative ways to manage pain, dysfunction, or health enhancement.

Benefit to chiropractic

Ultimately, what is best for patients is best for chiropractic. Direct benefits for the integrative chiropractor include sharing information with medical physicians, access to better resources and diagnostics, and a broader base of patients who could benefit from chiropractic treatment and management. Indirect benefits include establishing reputation and stature as a community health resource. Chiropractors may call primary care physicians on a patient’s behalf to request more tests, evaluate for prescription medication, report drug interactions or side effects, or request imaging studies.

Economic reasons

The University of Maryland’s Complementary Medicine Program ventured that chiropractic has the most convincing evidence for cost-effectiveness. [17] Cost-benefit studies are very encouraging, [53] with prospective ones currently underway. [54] Studies less favorable toward chiropractic in terms of cost benefit [55] have often ignored ancillary medical expenses in diagnostic testing and disability. Chiropractors’ reimbursement does not usually include incentives to minimize intervention and associated costs, though chiropractors have been obliged to share in risk management pools in health management organizations. With an eye toward efficacious treatment, training in safe care, and low risk of side effects, great potential exists for a cost-benefit contribution by chiropractic and the integration of chiropractic services into general health care delivery.

A demonstration currently realizing chiropractic’s potential for savings is Alternative Medicine, Inc. (AMI) of Chicago. Founded by James Zechman and Richard Sarnat, MD, the company enlists chiropractors as deliverers of some primary care services. As a result, in the first 12 months of operation, AMI patients experienced hospitalization rates reduced by 65%, outpatient procedures reduced by 85%, and 56% less use of pharmaceuticals. [56]

External barriers to integration

Approximately 10% of medical physicians in Great Britain refer to chiropractors on a regular basis, while about 35% more refer to them irregularly or only at the request of their patients. [43] In the United States, up to 50% of medical physicians have referred patients at least 1 time to chiropractors; [13, 14, 21, 22] one recent study found as many as 65% of physicians refer to chiropractors on “some” basis. [7] The same study found that 98% of chiropractors refer to medical physicians. Most of what medical physicians learn about chiropractic is what patients report. Communication between physicians and chiropractors is rare, with only about 25% of referrals from both professions accompanied by medical or health information. [7] Medical physicians say that chiropractors’ reports often contain confusing terminology, which reflects poorly on themselves. [7, 43] Other studies indicate medical doctors are uncomfortable with chiropractors taking on the primary care designation1, [7, 20, 31] and feel that chiropractors compete with them when claiming primary care status, rather than serving a complementary function. [7]

Concerns for safety

One misunderstanding among a few medical providers is that spinal manipulation is risky. Risks can be classified as direct safety of the treatment or indirect error of omission (a missed diagnosis or misdiagnosis). The safety data on spinal manipulation are very good, though the perception is that cervical adjustments present a significantly increased risk for stroke. [37, 57] The second safety issue is the error of delayed appropriate medical care. Studdert et al [46] show actual claims for either issue to be very low as reported by the largest chiropractic malpractice carrier, National Chiropractic Mutual Insurance Co.

Figure 1

Figure 2 The purpose of algorithms A and B (Figure 1 + 2, see Appendix) is to illustrate chiropractic competence in diagnosis and triage to the satisfaction of primary care providers, usually internal medicine and family practice specialties. It is designed to demonstrate careful examination and diagnosis and the consideration of “red” and “yellow” flags of back symptoms as considered by the integrative chiropractor.

Medicine’s role as primary health resource

Since many patients rely on their primary care physician as a health resource, medical doctors’ opinions of chiropractic is a major factor for referrals to chiropractors. The average consumer still looks to the medical doctor as a primary health information resource. Fifty-seven percent of Americans say they would more likely use CAM if those services were available from their own physician. [6] Indeed, some medical physicians claim training in manipulation methods (up to 27%), [21] and others are interested in obtaining manipulation training (68.4%). [13] But, medical doctors are not likely to adopt spinal manipulation as a therapeutic modality.

A study published in Spine [15] concluded that spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) delivered by primary care medical physicians offered only a modest benefit to patients, but patients experienced more benefit with a higher frequency of treatment. More patients recovered after the first office visit of the medical “manual therapy,” and time to recovery for the SMT group was significantly better: 7.8 days for manual therapy versus 11.1 days without. But interestingly, there were no overall differences in pain measures, days absent from work, and patient satisfaction between the medical manipulation and normal medical management groups.

Issues of scientific, habitual, and subtle bias

Medical habit or custom treats the medical patient with low back pain by well-established protocols of medication and physical therapy. If the clinical presentation is complicated, has an underlying comorbidity, or does not respond to conservative medical measures, the patient is referred to neurology, neurosurgery, orthopedic surgery, or physiatry. Chiropractic is virtually unknown and not considered as a viable treatment option. As an example, a recent patient brochure on low back pain based on Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) Guidelines [28] was created for Camino Medical Group in Sunnyvale, California. The brochure omitted spinal manipulation as an evidence-based treatment for low back pain, [58] even though it was recommended by the guidelines cited in the brochure. [28] By contrast, the current Stanford University Emergency Department manual used by medical residents and Palmer College of Chiropractic West faculty supervising the Stanford Emergency Department rounds program for chiropractic interns listed the AHCPR recommendations in full and manipulation as the physical treatment for low back pain with the greatest evidence. [59]

Chiropractic research is relatively new to universities and the medical world. Given the history of chiropractic and medicine, even under blind peer review, there is a subtle dismissal of CAM and chiropractic content as not scientific or not worthy of scientific inquiry or report. [60] Furthermore, research methodology for chiropractic services in many ways encounters the same difficulties inherent in psychological research in attempting to control many intrapersonal and interpersonal factors. Such data are not as “tidy” in controlling for the complexity of nonspecific factors or “experimental confounders” that unintentionally intrude, compete with, or contribute to clinical outcomes, and therefore must be controlled by careful experimental design. While some would simply dismiss these factors as placebo, another approach would attempt to identify and harness any healing factors as valuable in contributing to better clinical outcomes. Issues of chiropractic research range from setting up comparable placebo groups, difficulty in double blinding (even the naieve patients can tell when they are treated), and ensuring true random assignment to treatment groups. Another issue pertains to a population of chiropractic “responders” who especially benefit from SMT and chiropractic management. In assigning treatment-naieve subjects to assure double blinding, researchers may be excluding a subgroup of patients that benefit from chiropractic treatment. [61]

Obvious ostracism persists in the guise of “quack busters,” such as the National Association for Chiropractic Medicine (NACM) and the National Council Against Health Fraud in Loma Linda, California. Another contributor to chiropractic’s ostracism from mainstream health care is simply institutionalized economics. These are the same reasons that keep medicine from improving its own delivery system today. [62, 63] The US health care system, including health insurance, is ripe for innovation, but there are few economic incentives to do so, as long as employers are willing to pay higher health premiums without seeking alternative benefit plans. There is a potential for savings by integrating chiropractic into medical systems at the delivery level. Based on figures mentioned earlier, avoiding even 1 lumbar fusion or laminectomy per month in any single medical group or hospital could generate direct cost savings of up to $2,000,000 per year. [27] And this figure does not include indirect costs of disability, rehabilitation, and iatrogenic costs. But even with cost benefit, it is not clear that medical groups or employers would realize actual savings from integrative chiropractic, given the current models of health care reimbursement and its lack of incentives for improvement.

The inherent bias was summarized by Carol Freshley: [35]“Until reimbursement policies are changed to favor services that maintain health, the current health organization will have a difficult time spending precious resources to keep people out of the health care organization or out of the physician’s office. It would be a bit like the chairman of General Motors telling his stockholders that the company was going to spend $10 million in the coming year to teach people to ride the bus!”

Consumer attitudes

Reason number 1 that consumers do not try alternative medicine is the possibility of unknown side effects, as cited by 65 percent of American health consumers in a recent survey. [6] Fifty-one percent of those surveyed said they were deterred by lack of scientific proof. Households with children were almost evenly split on whether or not they would consider alternative treatment for their kids (53% for it, 47% against). [6, 20] To the consumer, chiropractors treat mostly conditions of pain and dysfunction, especially of the back. One in 3 patients with back pain see a chiropractor. [4]

Consumers also do not want to give up their medical physicians. They want a medical doctor with their chiropractic doctor. [23, 33] In fact, Michelle Teitelbaum’s64 study of the public’s view of chiropractic as primary care versus direct access suggested that the public prefers medical doctors as their primary care providers, at least for now. Thirty-two percent would seek alternative treatment only if they were diagnosed with a problem that was easily treated medically. Interestingly, when a complex, potentially fatal disease is diagnosed, nearly 60% of Americans say they would consult CAM practitioners. Only 11% would seek CAMs during normal healthy episodes for preventive reasons. [6]

According to an article in Frontiers of Health Services Management,35 there are 6 truths of the entire CAM phenomena:

People want to be in charge of and assume responsibility for their own functional well-being. They want self-directed care. Degrees, training, and consent forms (“seen as the ultimate insult”) do not impress them.

People want health information and disease-specific information.

People want choice. Choice allows personal decision for their health care. They expect their choices to be respected.

They want their physician to participate in the information-sorting process. “A seven-minute office visit is not seen as participation” (p. 9).

People “want seamless integration along the full continuum of health care services” (p. 9).

They want to keep their philosophy of health, even though they are in a medical environment.

Internal barriers to integration

Disagreements within the chiropractic profession over the importance of several key issues may impede chiropractic integration. Some of these include the subluxation as central to chiropractic diagnosis and scope of intervention, how chiropractors define their scope of practice relative to other providers in the integrative setting, [7] and the challenge to communicate the chiropractic contribution in terms of health care solutions rather than philosophy. These points are outlined below.

The pitfalls of identifying the chiropractic profession too closely with the subluxation were discussed aptly by David Chapman-Smith in the Chiropractic Report, [65] and the reader is referred to that article for a comprehensive review of the issue. With chiropractic identity pinned on subluxation, subluxation as fundamental to practices of “principled” chiropractic, its relationship to innate vitalism, and the use of it as a clinical outcome without regard to patient symptoms, it remains a sticky issue with biomedicine and thus also with integration. Even if the subluxation is ultimately vindicated in the future as true, for now the subluxation remains a barrier to integration.

And yet, integrative chiropractors must also describe their craft as distinct from other providers. Since chiropractors have been isolated from health care systems, it can be challenging to describe clearly how and where chiropractic services complement physiatry, physical therapy, osteopathy, and medicine generally. In musculoskeletal applications, chiropractic care needs also to be differentiated from orthopedics, neurosurgery, and spinal anesthesia, since these professionals have such an overlap of diagnostic cases seen. Also, a working familiarity of internal medicine and family practice specialties would be very useful, since chiropractic services complement these specialties.

In integrative environments, chiropractors must communicate effectively to the rest of health care. A large misconception among medical directors about chiropractors is that physical therapists deliver the equivalent of chiropractic services. The 2 professions seem very similar at a superficial level, because they both perform spinal manipulation, manage musculoskeletal rehabilitation, deal with chronic pain, and use many of the same ancillary therapies (eg, ultrasound and electrical muscle stimulation). In fact, the recommendations for SMT from the 1993 AHCPR Low Back Pain Guidelines were trumpeted by physical therapists as much as they were by chiropractors. After all, the research supporting the effectiveness of spinal manipulation was conducted by physical therapists as well as chiropractors.

Table 2 At least 1 study showed medical physicians were clearly more comfortable with referring to physical therapists than chiropractors. [47] The philosophical differences between physical therapy and chiropractic are not pertinent to questions of health care delivery. The patient wants to feel better, the hospital wants to save costs, and insurance carriers want to limit risk. Can chiropractic treatment help? Explanations of the important distinctions between chiropractic and physical therapy are found only in the application of each. Though there is overlap in types of conditions treated by both, such as low back pain, neck pain, and headaches, the 2 professions have evolved qualitative differences in cases treated and patient preferences. Table 2 is an attempt to express these qualitative distinctions between the 2 professions in terms of application.66

The future of integrative chiropractic

Diagnosis

Chiropractors are trained to be very competent diagnosticians, and precision diagnosis has the potential to improve health outcomes. For example, the differentiation of discogenic pain from zygapophyseal pain is a fine but important one that should lead to 2 very different clinical pathways for back pain management and their associated outcomes. Getting patients on the right path to recovery at the earliest time with appropriate disability management has the potential to enhance outcomes and lower costs. This should enhance efficiencies and lower costs. Therefore, continually improving diagnostic skills will be a priority for the integrative chiropractor.

Diagnosis will need to extend to evaluating back pain as a syndrome within the larger medical and biopsychosocial context. [50] This points to the heart of integrative thinking—treatments are often more contributory to outcomes rather than the single causal intervention. Each treatment or therapy has a potential role in recovery of certain problems. The role of spinal manipulation may be greater in resolving facetogenic pain than discogenic pain, for example. But SMT may have some role in both. Clinical wisdom offers a starting point, and triage for the treatment protocol maximizes recovery with minimal risk.

Collaborative education, clinical training, and research

The training and clinical experience of chiropractors and chiropractic students provides little exposure to new medical procedures, the vocabulary of medicine, pharmaceutical use, and drug interactions and drug-herb interactions. In 1999, at the request of education leaders at Palmer College of Chiropractic-West, the author designed and coordinated offsite clinical rounds for chiropractic students at a tertiary spine care center in Daly City, California, The Spinal Diagnostics and Treatment Center (SDTC). At this facility, discograms, proliferative therapy, facet injections, nerve blocks, nucleoplasty, and intradiscal electrothermy (IDET) were performed. Back care at SDTC is based on the skills of anesthesiologists. Participating students spent 4 days each in observation of these tertiary spine procedures. Students were required to wear surgical scrubs, masks, and surgical hats.

The Medical Spine Care Terminology Glossary (attached) includes a clinical aid that identifies concepts and words for doctors in interdisciplinary spine care settings. Integrative-minded Palmer College of Chiropractic-West students also have opportunities for observing acute care management at Stanford University Hospital Emergency Department and may soon have opportunities to observe chronic condition management at the local Veterans Administration Hospital through this program. The intention was to provide chiropractic students with the opportunity to observe cases and medical management that they may encounter in patient questions in integrative or regular practice.

Chiropractic education must help students accept and deal with many models of health and disease because there are many factors that lead to both. Chiropractic as an art is valuable in some cases because the highly developed palpatory and kinesthetic skills that are required of the chiropractor directly contribute to the recovery of certain kinds of maladies. In many other cases, however, chiropractic services provide only an important complement to the healing process and not the sole cause. Being part of a team of providers with the patient’s health and well-being as its centerpiece is integrative medicine.

Integrative chiropractors will have an ongoing need for distilled, interpreted, and current research knowledge, including critiques and clinical implications. Such studies pertaining to chiropractic and their proper interpretation are very important to research-oriented medical colleagues. As an example, when Cherkin et al [38] published a study comparing chiropractic care, physical therapy, and a 50–cent exercise booklet for back outcomes, there were no differences in outcome among the 3 groups. The booklet was found to be as effective as the other 2 active interventions, at a fraction of the cost of treatment. The study later received low methodological scores by Feise [67] and was criticized for 6 methodological weaknesses by Freeman and Rossignol [68] in a subsequent letter to the Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics.

Understanding psychosocial and placebo issues

Assessing responsiveness to treatment from contributory psychosocial issues such as depression prior to embarking on any treatment program may become a standard of care in the future health care system. Mood, depression, and psychological state have an established role in recovery from back surgery. [69] Waddell [50] states that a large proportion of back disability caused by fear-avoidance rivals the actual physical cause. Spine surgeons in Palo Alto, California routinely administer a biopsychosocial assessment instrument to help determine suitability for surgery and to predict probable surgical outcomes. [70] Chiropractors are generally less informed on how psychosocial issues affect condition treatment and recovery.

Denying mind-body factors in health, disease, and particularly back pain and disability but attributing all pain and dysfunction to a mechanical or chemical causation implies a lack of knowledge of a growing body of scientific literature on the subject. [71] This impedes proper integrative protocols, since psychosocial issues could not be considered properly and back pain might prove intransigent to mechanical interventions alone. Issues of the spiritual, psychological, and community contexts of patients must be considered in integrative approaches.

Psychosocial factors contribute a percentage to the cause of disease and also contribute a percentage to recovery, or at least to maximum treatment benefit. [50] Chiropractors that include biopsychosocial contexts in the assessment of pain and dysfunction will position themselves on the cutting edge of spine care. Attributing spinal complaints only to a lesion may be considered as a restrictive mechanical model that favors the practitioner’s approach.

Adopting emerging technologies

Biotechnologies and associated companies are proliferating due to recent advances in gene splicing and in sequencing the human genome. Integrative chiropractors could assume an important role in this new field. With the genome deciphered and mapped, potential health risks and life-style remedies will be specified at birth. This implies a lifetime of vigilance and life-style directives to minimize phenotypic disease expression. Chiropractors who manage the bigger picture of patient life-style factors will adopt this new technology in support of that endeavor. Patients will need coaching on the interpretation of their genetic profiles and planning for a life of optimum health. Ultimately, perhaps a new type of reimbursement model based on compliance and prevention through reduced health risk behaviors will evolve. Chiropractors are perfectly positioned to guide others in health preservation, if they will embrace the language of the gene and grow into this greater role. [32]

Operating on a medical-chiropractic continuum

Integration of chiropractic implies a blending of chiropractic and medical services in health care delivery. It does not imply that chiropractic care will become more like medicine or that chiropractic will become a musculoskeletal specialist within medical care. Chiropractic identity and integrity must be maintained in the integration into general health care delivery, not losing sight of its unique contribution. The “solo holistic chiropractic physician” does not represent integrative medicine unless he or she works with biomedical providers in an integrated manner. Practice standards for integrative chiropractors may eventually evolve that guide patient treatment for a specified and finite therapeutic trial period. Then, without a reasonable reduction of symptoms, patients will be referred to the next best treatment, resources, or providers—those with low-risk procedures and best evidence for clinical outcome.

Chiropractic integration from the medical side

In the health care business literature, advice is given to medical groups and hospital executives to be sensitive to the “C” word (chiropractic): “Although the presence of chiropractic services as a component of complementary services is highly desirable from a revenue-generation standpoint, the sensitivity of this issue with physicians must be recognized.” [3]

Table 3 Consultants warn that fully integrating CAM into the seamless continuum of care requires commitment from the top down. The integration process is more than simply tweaking the current system; innovation and change management are required. A summary of the potential advantages of CAM integration into a medical delivery system derived from Freshley and Carlson [35] are outlined in the Table 3.

The medical community is thus tiptoeing into the CAM arena by offering courses about chiropractic and the rest of CAM. In 1998, 75 of the 123 accredited medical schools like Columbia, Johns Hopkins, University of California, and Stanford offered courses in alternative medicine, compared to 15 in 1993. [72] In response to a reader poll, the American Medical Association published issues on CAM in November 1998.

Table 4 Models that are under review from the medical business perspective are solo practitioners, physician-based practices, academic and research initiatives, wellness centers, provider networks, and hospital-based initiatives. [44] Hospitals are guided to affiliate with extant field practices or fold them into the current facility to incorporate existing patient bases.

For those medical physicians interested in working with chiropractors, Curtis and Bove [73] have identified characteristics of compatible chiropractors (Table 4).

Communicating integrative chiropractic

In integrating chiropractic into orthodox health care delivery, the role of the chiropractor must be expressed in a manner that conveys the chiropractic distinctiveness from other health care professions but without dogma. Perhaps the most essential description of chiropractic’s role in health care is in the unique emphasis on the spine’s role in health and disease. There are at least 2 underlying assumptions in this approach. First is an intimate knowledge of the structure and function of the spine itself. Second, there is a predisposition toward detecting disease processes prior to health problems before they become clinically manifest.

Chiropractors may take for granted their unmatched knowledge of the spine, joints, neuroanatomy, adjacent musculature, pelvic ring, and sacroiliac joints taught in all chiropractic curricula by lecture, laboratory, and clinical experience. Histological and embryonic development, blood supply, enervation, and sources of pain are studied in detail. Taking and interpreting radiographs, ordering and using MRI data, and screening for spinal pathologies and musculoskeletal mimicking diseases are skills fundamental to passing national and state board examinations. Such knowledge and skills aid in the finer differential diagnoses of pain syndromes.

The second implicit idea refers to early detection of the disease processes and prevention. There are 2 fundamental approaches to disease treatment. Both have their metaphorical roots in Greek mythology. First, the allopathic approach interrupts the natural course of disease. [60] This may be referred to as the Aesclepian model, named for the son of Zeus and Greek god of medicine, Aesclepius (who, incidentally was taught to be a physician by the infinitely wise Centaur Chiron). The second model rests on the removal of barriers to healing. This is the hygienic model referring to the Greek goddess, Hygeia, a daughter of Aesclepius who was subsequently promoted to Goddess of Health. [74]

Much of the current disease burden in society has its origin in life-style habits or “factors.” [75, 76] Health promotion as a host orientation, rather than disease or symptom orientation, emphasizes changing these habits to improve recovery. The host orientation question is “What can be done to enhance the patient’s robustness to disease?” This contrasts with directly treating agents of infection. For economic reasons and to alleviate an overburdened health care system, there will be a growing need to emphasize self-care, both in terms of disease prevention and compliance for diagnosed conditions. This health guidance can be of strategic advantage for the chiropractic profession because of its long history of emphasizing restoring health rather than treating disease, and because this promises enormous savings in treatment and iatrogenic mistakes. [32]

The practice or the application of musculoskeletal and neuromusculoskeletal intervention builds expertise in treating pain, injuries, and dysfunction of the musculoskeletal system. For example, knowledge of the inflammatory cascade and immune response is fundamental to managing injuries. The tissue repair cycle needs to be controlled to minimize adhesion formation and tissue damage and maximize restoring function. While quite efficient in isolating and eliminating infection, the inflammatory response to musculoskeletal injury can actually increase damage. Restoring function quickly means better recovery and reducing the chance of disability. This is fundamental to most chiropractic management. [50]

Table 5 Expertise in spinal anatomy and function, a health promotion mind-set, a holistic host orientation, a high degree of kinesthetic skills, and mastery in musculoskeletal management are not unique to chiropractic, but perhaps uniquely combined in chiropractors. Table 5 contrasts general chiropractic and biomedical areas of emphasis. Described in terms of these qualities, the chiropractic profession has a unique and very valuable contribution to integrative health care. These are concepts that communicate to today’s health care policymakers and physicians.

Summary of chiropractic research

Studies of chiropractic treatment that assess the effects of only 1 treatment such as spinal manipulative therapy are called efficacy studies. While 94% of SMT in the United States is performed by chiropractors, the service is also offered by osteopaths, physical therapists, and by some Ayurvedic and Chinese medicine practitioners. Overall, SMT studies by all SMT providers suggest a 34% improvement at 3 weeks over patients not receiving SMT. [36] Back surgery and other medical treatments of the back are less predictable in their contribution to recovery. [31] While more back surgeries per capita are performed in the United States than most other countries, [30] its long-term effectiveness may be as low as 1%. [28]

Effectiveness studies of comprehensive chiropractic management that includes more than spinal manipulation therapy are rare. Comprehensive chiropractic management would include SMT, exercise, nutrition, stress management, and perhaps other prescriptions. For example, chiropractic as a treatment of asthma has not been supported by research, yet the anecdotes persist. Though the efficacy of spinal manipulation for childhood asthma was evaluated, [77] the effectiveness of broader chiropractic management of childhood asthma is still unknown. It is important to note which type of research has been done before extrapolating to clinical practice or health care policy.

According to the current best evidence, chiropractors have great potential to alleviate low back pain, headaches, [78] and neck pain and their associated costs. Thirty-one million incidents of low back pain per year costing $50 billion in direct treatment and up to $50 billion in indirect costs add up to a major public health problem. [29] For a certain profile of back pain, chiropractic management is effective, inexpensive, and safe. With only 1 in 100 back surgeries providing long-term relief, physical therapy modalities not particularly effective, [28] and conservative medical management limited in results, the chiropractic profession is positioned to offer an enormous contribution to the best practices in health care, both in cost and benefit.

Chiropractic’s potential contribution for improving public health

Of the 2.1 million US deaths in 1990, about 50% were attributed to 9 behavioral causes that were preventable. In descending order of significance, they are tobacco, diet and activity patterns, alcohol, microbial agents, toxic agents, firearms, sexual behavior, motor vehicles, and illicit drug use. [76] Tobacco alone will account for 9% of deaths in the United States. [32]

In terms of morbidity, which eventually translates into demand for medical and health services, an index of the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) formulated by the Word Health Organization ranks the top 10 diseases by disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 1990 and projected for the year 2020. The 1990 top 10 causes of disability-adjusted life years included infectious diseases as top causes for illness disability, such as lower respiratory infection, diarrhea disease, tuberculosis, and measles. For 2020, unipolar major depression and traffic accidents climb in frequency of occurrence. Human immunodeficiency virus will continue to be a major illness in 2020. [76] Ischemic heart disease was the top cause of disability in 1990 and will remain so through 2020, according to the GBD.32 These morbidity assessments represent the entire world, not only the United States. Many of these familiar diseases can be affected by life style modifications such as nutrition, exercise, rest, and stress management. [32] Chiropractic can contribute to the disease burden through health risk appraisal, genotypic information, and motivating and monitoring health.

Future roles

Most agree that CAM will play a significant role in the health care management of the future. With additional research into cost-benefit ratios and clinical effectiveness, according to Dr. Stephen Straus, director of National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, the stigma of certain CAM therapies as unconventional will be replaced by a new health care paradigm. “By 2020 these interventions will have been incorporated into conventional medical education and practice, and the term ‘complementary and alternative medicine’ will be superseded by the concept of ‘integrative medicine’.” [79]

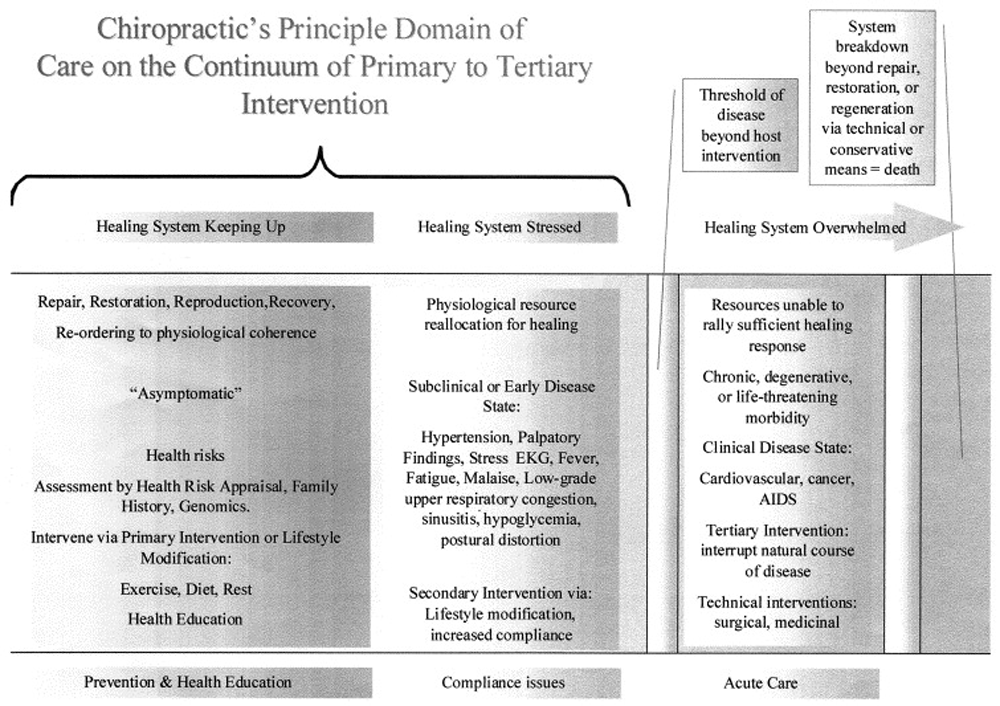

Figure 3 Clem Bezold [32] points to the possibility that chiropractors may have a greater function in prevention of health risks and enhanced compliance for chronic conditions. In the model of primary, secondary, and tertiary intervention, [80] chiropractic has a potential contribution in primary prevention and early detection and treatment through life-style modification and medical compliance (Figure 3).

A future medical anthropologist may look back to the end of the second millennium and understand why CAMs dramatically increased in popularity. By the year 2001, acute trauma and many infectious diseases were capably managed by allopathic medicine, perhaps with the notable exception of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), but the cost of health care was astronomical. [25, 81] In addition, widespread indiscriminate use of antibiotic agents contributed to resistant strains of bacterial infections. Some of the biggest killers—cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancers, and accidents—were largely preventable by modifying life choices or applying host-focused interventions.

By that time, chiropractors could address disease and save health care costs by offering personal guidance based on patient history, family history, and genetic profile and monitor compliance and progress toward health improvement by programs at home and work. Chiropractors could also address the greater home and community context in their roles as contributing to health50 and apply low-risk treatment protocols, including hands-on techniques. In addition, chiropractors, may scan for “diseases of meaning” [32] that manifest as depression, certain accidents, substance abuse, and violence. Longevity with an improved quality of life may be the objective of the new medicine. In shifting to practicing prospectively from reactively, from disease to host, health care will sharpen its focus on primary prevention by assessment of health risks and secondary intervention (eg, detecting and modifying early stages of a disease process).

Future implications for chiropractic integration and topics for research in integrative health care should focus on what integrative medicine means in terms of the personal integration of the healer. Also in need of careful consideration are whether syndromes rather than symptoms are treated and whether inductive versus deductive methods should be emphasized in gathering chiropractic and integrative medicine clinical data.

Conclusion

CAM utilization is on the rise, driven to date by public interest. Chiropractic leads in utilization of CAM therapies. There is potential for the chiropractic profession to be integrated into medical delivery systems where most medical physicians (the younger ones and the ones in primary care) already believe chiropractic is a legitimate profession providing effective care for certain conditions. Physician referrals lag behind their stated beliefs in chiropractic efficacy, however. This is due in large part to barriers, both external and internal, to communication differences and deficits. In the pursuit of greater marketing advantage, some medical groups are considering integrating chiropractic. But there are cost-benefit reasons for managing chronic and musculoskeletal pain with chiropractic care.

In addition, there are health care system demands that may require a greater degree of chiropractic participation in service delivery. At current increasing rates of utilization due to an aging and growing population and accounting for nurse practitioners, physician assistants, nurse-midwives, and increases in medical school graduates and foreign doctors, there will still be a shortfall of 50,000 physicians in 2010 and as many as 200,000 in the year 2020. [82] Chiropractic could take the initiative in solving this problem.

To meet the potential demand for integration, chiropractors need to learn about communicating in and with a medical environment in terms of solutions, not philosophies. Chiropractors should build opportunities to work with medical doctors in chiropractic education, postgraduate education, and clinical settings. Chiropractors should be familiar with medical specialties and procedures. They also need to express their contribution to health care succinctly and without dogmatic overtones. To become a major player in the health care of tomorrow, chiropractors will need to add to their skills by including health risk assessment and life-style guidance. Their skills should include expertise in the domains of primary and secondary intervention.

Given the currently known strengths of chiropractic technology, integrative medicine treatment protocols for uncomplicated back pain, neck pain, and headache could include chiropractic as a first choice of care. There is evidence of reduced demand on medical benefits and health care expenses by utilization of chiropractic services, [56] but the full potential is yet to be realized. Ultimately, chiropractic may have a role in healing health care itself. The chiropractic profession is now at an important juncture in its evolution and is presented with the opportunity to define its future roles in health care. But it must grow and adapt to this new terrain with vision, grace, and a sense of humor. According to current trends, clinical communication and patient management skills in an interdisciplinary environment will be vital to chiropractors in keeping pace with the future of health care and the public’s needs.

The future of integrative chiropractic will depend on the profession’s self-perception and articulation of its own strengths in nondogmatic terms. But chiropractic in some ways represents exactly where health care, as a whole, needs to go, and chiropractic is a valuable complement to health care delivery as a whole.

Appendix.Note 2.1 red flags in low back pain presentation

Features of cauda equina syndrome (especially urinary retention, bilateral neurological symptoms and signs, saddle anesthesia)—this requires very urgent referral

Significant trauma

Weight loss

History of cancer

Fever

Intravenous drug use

Steroid use

Patient aged over 50 years (without a history explaining the back pain)

Severe, unremitting nighttime pain

Pain that gets worse when patient is lying down

Elevated antinuclear antibody (ANA), sedimentation rate, HLA-B27, or other evidence of autoimmune or systemic inflammatory process

Note 3.1 yellow flags in low back pain presentation

Attitudes and beliefs about back pain

Emotions

Behaviors

Family

Compensation issues

Work

Diagnostic and treatment issues

A working diagnosis or comorbidity of rheumatoid arthritis or connective tissue disease

Note 4.1 red flags in cervical pain and headache presentation

Unexplained vomiting without nausea

Headache sudden onset, extremely intense, unusual for patient ? subarachnoid hemorrhage

Headache with neurological deficits ? transient ischemic attack (TIA)

Upper motor involvement such as gait/balance/seizure

Associated personality change

Pus discharge from nose

Associated loss of strength

Unusual loss of vision

Feeling of “hollowness” in head

Unequal pupillary size or response

Headache with recent excessive fatigue (cancer or arteritis)

Headache with shortness of breath (heart or lung disease)

Combination of fever and headache (meningitis or encephalitis)

Nuchal rigidity

New onset in patient over age 50 ? giant cell arteritis or tumor

References:

Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Van Rompay M, Kessler RC.

Trends in Alternative Medicine Use in the United States, 1990 to 1997:

Results of a Follow-up National Survey

JAMA 1998 (Nov 11); 280 (18): 1569–1575Eisenberg, D.M., Kessler, R.C., Foster, C., Norlock, F.E., Calkins, D.R., and Delbanco, T.L.

Unconventional Medicine in the United States: Prevalence, Costs, and Patterns of Use

New England Journal of Medicine 1993 (Jan 28); 328 (4): 246–252Nadel, M.A.

Observations from a bottom-line oriented true believer.

Front Health Serv Manage. 2000; 17: 31–35Kaptchuk, T.J. and Eisenberg, D.M.

Chiropractic: Origins, Controversies, and Contributions

Arch Intern Med 1998 (Nov 9); 158 (20): 2215-2224White, A.R., Resch, K.-L., and Ernst, E.

Complementary medicine (use and attitudes among GPs)

Fam Pract. 1997; 14: 302–306Fetto, J.

Quackery no more.

Am Demogr. 2001; 23: 10–11Mainous, A.G. 3rd, Gill, J.M., Zoller, J.S., and Wolman, M.G.

Fragmentation of patient care between chiropractors and family physicians.

Arch Fam Med. 2000; 9: 446–450Pelletier KR, Marie A, Krasner M. et al.

Current Trends in the Integration and Reimbursement of Complementary and

Alternative Medicine by Managed Care, Insurance Carriers, and Hospital Providers

Am J Health Promot 1997 (Nov); 12 (2): 112–122Anonymous.

Hospitals slowly adopting CAM offerings, but many missing out on opportunities.

Health Care Strateg Manage. 2000; 18: 17Anonymous.

Complementary partnership.

Trustee. 2001; 54: 3Rees, L. and Weil, A.

Integrated medicine (imbues orthodox medicine with the values of complementary medicine)

BMJ. 2001; 322: 119–120deMaye-Caruth, B.

Complementary medicine (health care trends for the new millennium)

Hosp Mater Manage Q. 2000; 2: 18–22Berman, B.M., Singh, B.K., Lao, L., Singh, B.B., Ferentz, K.S.

Physician’s attitudes toward complementary or alternative medicine (a regional survey)

J Am Board Fam Pract. 1995; 8: 361–366Astin, J.A., Marie, A., Pelletier, K.R., Hansen, E., and Haskell, W.L.

A review of the incorporation of complementary and alternative medicine by mainstream physicians.

Arch Intern Med. 1998; 158: 2303–2310Curtis, P., Carey, T.S., Evans, P., Rowane, M.P., Garrett, J.M., and Jackman, A.

Training primary care physicians to give limited manual therapy for low back pain (patient outcomes)

Spine. 2000; 25: 2954–2961Perry, R. and Dowrick, C.F.

Complementary medicine and general practice (an urban perspective)

Complement Ther Med. 2000; 8: 71–75Weeks, J.

Is alternative medicine more cost-effective?.

Med Eco. 2000; 77: 139–142Menke JM.

The integrative chiropractor.

J Am Chiropr Assoc 2000;37:32-3Boucher, T.A. and Lenz, S.K.

An organizational survey of physicians’ attitudes about and practice of complementary and alternative medicine.

Altern Ther Health Med. 1998; 4: 59–65Crock, R.D., Jarjoura, D., Polen, A., and Rutecki, G.W.

Confronting the communication gap between conventional and alternative medicine (a survey of physicians’ attitudes)

Altern Ther Health Med. 1999; 5: 61–66Berman, B.M., Singh, B.B., Hartnoll, S.M., Singh, B.K., and Reilly, D.

Primary Care Physicians and Complementary-Alternative Medicine:

Training, Attitudes, and Practice Patterns

J Am Board Fam Pract. 1998; 11: 272–281Cherkin, D., MacCornack, F.A., and Berg, A.O.

Family physicians’ views of chiropractors (hostile or hospital?)

Am J Public Health. 1989; 79: 636–637Druss, B.G. and Rosenheck, R.A.

Association between use of unconventional therapies and conventional medical services.

JAMA. 1999; 282: 651–656Astin, J.A.

Why patients use alternative medicine (results of a national study)

JAMA. 1998; 279: 1548–1553Pelletier KR.

Stanford Corporate Health Program [introductory letter].

Stanford (Calif): Stanford Center for Research in Disease Prevention; September 1, 1999Pear R.

Propelled by drug and hospital costs, health spending surged in 2000.

New York Times. January 8, 2002:A14Schlapia A, Eland J.

Multiple back surgeries and people still hurt. Available at:

http://pedspain.nursing.uiowa.edu/CEU/Backpain.html

Accessed April 22, 2003Stanley J. Bigos, MD, Rev. O. Richard Bowyer, G. Richard Braen, MD, et al.

Acute Lower Back Problems in Adults. Clinical Practice Guideline No. 14.

Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, [AHCPR Publication No. 95-0642].

Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1994Grossman, R.J.

Back with a vengeance.

HR Magazine. 2001; 46: 36–46Deyo, R.

Low back pain.

Sci Am. 1998; 279: 48–53Carragee, E.

Desperate diseases grown.

Spine. 2001; 26: 2179Institute for Alternative Futures.

The Future of Chiropractic: Optimizing Health Gains

NCMIC Insurance Group and

Foundation for Chiropractic Education and Research

Alexandria, VA; (1998)Christensen MG, Kerkhoff D, Kollasch MW.

Job Analysis of Chiropractic 2000

Greeley (CO): National Board of Chiropractic Examiners, 2000.The Landmark Report on Public Perception of Alternative Care

1998 nationwide study of alternative care.

Landmark Healthcare, Inc; 1998Freshley, C. and Carlson, L.K.

Complementary and alternative medicine (an opportunity for reform)

Front Health Serv Manage. 2000; 2: 3–14Shekelle, P.G., Adams, A.H., Chassin, M.R., Hurwitz, E.L., and Brook, R.H.

Spinal manipulation for low-back pain.

Ann Intern Med. 1992; 117: 590–598Coulter, I.D.

Efficacy and Risks of Chiropractic Manipulation: What Does the Evidence Suggest?

Integrative Medicine 1998; 1 (2): 61–66Cherkin, DC, Deyo, RA, Battie, M, Street, J, and Barlow, W.

A Comparison of Physical Therapy, Chiropractic Manipulation, and Provision of an Educational Booklet

for the Treatment of Patients with Low Back Pain

New England Journal of Medicine 1998 (Oct 8); 339 (15): 1021-1029Egger, E.

Physician buy-in, scientific data crucial to CAM programs. (21-3)

Health Care Strateg Manage. 1999; 17: 1Weil A.

Curious about chiropractic?

Dr. Andrew Weil’s Self-Healing Newsletter November 1999;1-7Sullivan, L.

An alternative fit.

Risk Manage. 2000; 47: 48–56Stanger, J. and Coughlan, B.

Complementary and alternative medicine (What employers need to know)

Compens Benefits Manage. 2000; 16: 1–8Brussee, W.J., Assendelft, W.J.J., and Breen, A.C.

Communication between general practitioners and chiropractors.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001; 24: 12–16McGrady, E.S.

Complementary medicine (viable models)

Front Health Serv Manage. 2000; 17: 15–28Center for gerontology and health-care research,