Nontraditional Therapies (Traditional Chinese

Veterinary Medicine and Chiropractic) in Exotic AnimalsThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract. 2018 (May); 21 (2): 511–528 ~ FULL TEXT

Jessica A. Marziani, DVM, CVA, CVC, CCRT

CARE Veterinary Services PLLC,

PO Box 132082,

Houston, TX 77219, USA

marzianidvm@gmail.com.

The nontraditional therapies of Traditional Chinese Veterinary Medicine and chiropractic care are adjunct treatments that can be used in conjunction with more conventional therapies to treat a variety of medical conditions. Nontraditional therapies do not need to be alternatives to Western medicine but, instead, can be used simultaneously. Exotic animal practitioners should have a basic understanding of nontraditional therapies for both client education and patient referral because they can enhance the quality of life, longevity, and positive outcomes for various cases across multiple taxa.

Keywords: Acupuncture; Alternative therapies; Chiropractic; Complementary therapies; Integrative therapies; Nontraditional therapies; Traditional Chinese Veterinary Medicine

From the FULL TEXT Article:

KEY POINTS

Nontraditional therapies can be used in conjunction with conventional Western

therapies to enhance patient outcome.Nontraditional therapies are often sought out by exotic pet owners; therefore,

overall understanding is important for general practitioners.Exotic animal species can benefit from the application of nontraditional therapies.

Traditional Chinese Veterinary Medicine is tailored to the individual patient

to optimize health.Chiropractic care can be used as preventative form of treatment and for

chronic conditions.

INTRODUCTION

In the broadest definition, nontraditional therapies are therapies that currently are not conventionally used in Western practice. Other terms, such as alternative, integrative, and complementary, are commonly used to categorize nontraditional therapies. However, no matter what nomenclature is used, all are considered the practice of veterinary medicine. [1]

According to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, a division of the National Institute of Health (NIH), approximately 38% of adults in 2007 were using some sort of complementary therapy. [2] Those same adults may seek similar complementary therapies for their pets. Therefore, even if complementary therapies are not a core part of a veterinarian’s skill set, it is still prudent to be grounded in general knowledge, treatment options, and how and when nontraditional therapies can be used effectively.

This general working knowledge of the subject will help veterinarians better educate clients in nontraditional therapies. Without a referral from their veterinarian, clients may research nontraditional therapies on their own if they believe that the treatments will be beneficial. A recent survey of competitive horse riders and trainers showed that of the 37% of the respondents that were seeking nontraditional therapies for their horses, only 7% were doing so in collaboration with their veterinarian. [3]

Practitioners who integrate nontraditional therapies and Western medicine can take advantage of the strengths of each. This integration of methodologies can deliver overall better results than Western medicine or nontraditional therapies alone. A working knowledge of nontraditional therapies and open dialogue can also enhance the veterinarian-owner relationship.

Table 1 This article is intended to expose the general practitioner to the 2 most common and sought out nontraditional therapies: Traditional Chinese Veterinary Medicine (TCVM) and chiropractic treatments. The descriptions of each are intended to provide a basic understanding of what additional therapies are available and how they can be effectively utilized. The article is not intended to train the general practitioner on how to perform these therapies. Attending a specialized training course is highly recommended. These are listed in Table 1. Alternatively, practitioners who are trained in nontraditional therapies but have not practiced on exotic animals will also find this article useful as a reference for species comparisons and differences.

INTRODUCTION TO TRADITIONAL CHINESE VETERINARY MEDICINE

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) used in Western culture is relatively new. TCM was first introduced to the United States when an aide to President Nixon became ill while Nixon was visiting China in the 1970s. This aide was treated successfully with TCM and thus TCM was prominently introduced to Western culture. Because it has been practiced in the United States only in the last 40 years, TCM is considered a nontraditional or complementary therapy. However, it is among the oldest recorded forms of medical practice.

Thousands of years ago, ancient farmers began identifying methods to treat their sick livestock and horses. Without horses, they would lose battles, be limited in travel, and unable to plow their fields. Without livestock, they would go hungry. Effective methods of treatment were passed down from generation to generation and, in this way, TCVM was born.

As TCVM was introduced to the Western world, modern advances were also added to the implementation of TCVM. Western practitioners changed from multiple-use needles to reusable sterile needles, and added electrical current and laser light stimulation to acupoints. [4] Western society also expanded TCVM to fit other species beyond livestock and horses.

TCM and TCVM are often difficult for the Western practitioner to understand because both take an entirely different approach to health and treatment of disease. The general overriding principle in Western medicine is control. If the spread of the bacteria can be controlled, the infection can be treated. In TCVM, the prevailing principle is balance. If the body is in balance, it is in good health. The diagnostics in Western medicine range from an examination to advanced imaging. Diagnostics in TCVM are limited to observation and examination of the tongue, pulse, and palpation of points throughout the body. Western medicine treats a disease, whereas TCVM treats an individual’s imbalance pattern. TCVM is so individualized that it is not effective in herd-health medicine. For example, 2 Netherland dwarf rabbits with radiologically similar spinal arthritis are treated with the same approach in Western medicine, probably with nonsteroidal antiinflammatories and/or a centrally acting opiate agonist. [5] In TCVM, those same 2 Netherland dwarf rabbits will be treated differently based on their individual disease pattern, not solely based on the diagnosis of the spinal arthritis.

Explanation of Traditional Chinese Veterinary Medicine Pattern Diagnosis

An overarching tenant of TCVM is that the absence of disease means that the body is in harmony and balanced. Illness occurs when the body is out of harmony and out of balance. To establish balance, the practitioner must first ascertain what is out of balance. Is the patient too hot or too cold? Is there too much (an excess) of something or too little (a deficiency) of something? Are there multiple deficiencies and excesses? TCVM treatments revolve around what is referred to as a pattern diagnosis. For a patient with a complicated chronic disease condition, that pattern diagnosis may change numerous times throughout treatment while working through each layer of the imbalance. A TCVM practitioner must constantly be reassessing the patient’s pattern as the treatment continues to achieve better results.

The essentials of balance start with Yin and Yang. The Yin and Yang are 2 supporting opposites. Without the other to balance the scale, either can get out of control. Yin characteristics are cold, rest, slowness, weakness, and night. Yang characteristics are the opposite of Yin: warmth, activity, speed, strength, and day. If there is not enough warmth to balance the cold, then cold wins out and the leading characteristic exhibited is cold. In TCVM, this is considered Yang deficient because the body is deficient of warmth. The opposite of Yang deficient is Yin deficient, which is described as being too hot because there is not enough Yin, or cold, to counteract the warmth from the Yang. There is species variability in how much Yin or Yang is possessed, especially when it comes to exotics. For example, reptiles and amphibians are naturally more Yin than most animals, whereas avians are more Yang than most animals. [6]

After identifying the Yin-Yang pattern, the practitioner must also identify the Zang-Fu pattern to know which organ system is deficient or in excess. The Zang organ systems are heart, kidney, liver, lung, pericardium, and spleen. The Fu organ systems are bladder, gall bladder, large and small intestines, stomach, and triple heater (similar to the Western circulatory system). The zang-fu organ systems are similar to the Western organs they are named after; however, in TCVM principles, each has additional or slightly different jobs than considered in a Western sense.

For instance, in TCVM principles, the kidney system not only functions as the kidney organ but also regulates bone, controls energy, and stores the essence of the body. [7] If a patient is diagnosed by an acupuncturist as kidney deficient, that does not necessarily mean that they have abnormal renal values. The kidney deficiency may be diagnosed based on the presence of arthritis, which suggests that the kidney system is not controlling the growth of bone. It is a good idea to support the kidneys in these patients with normal renal values but they are diagnosed as kidney deficient because they may have renal insufficiency later in life. The zang-fu organ system is very detailed and complicated beyond the scope of this introduction.

The basis of a TCVM examination is the evaluation of the tongue and pulse. A TCVM practitioner uses the quality and symmetry of pulses, and the color, shape, and texture of the tongue, to identify the disease pattern or come to a TCVM diagnosis. In most species, the tongue has round edges and is relatively flat, pink, moist, and smooth. For example, tongues that are coated in yellow and are dark red and swollen indicate too much heat in the body, or a Yin deficiency. When tongues vary in shape, color, and texture, using the tongue color for pattern diagnosis becomes more of a challenge. Reptiles, amphibians, and avians, for example, are not suitable species for tongue diagnosis. For birds, an alternative to tongue evaluation is to assess the color and characteristics of the vent and cloaca. [8]

In most species the pulse is taken bilaterally, comparing the contralateral pulse. The artery used depends on which is most assessable, usually the carotid or femoral artery. For most avian species, the brachial artery on ventral surface of the wing as it crosses the ventral surface of the humerus provides the most assessable palpable pulse. [8]

Pattern diagnosis in certain exotic species poses unique problems. Reptiles are particularly challenging because, typically, there is not a palpable pulse and their tongues do not follow the general TCVM characteristics. Therefore, pattern diagnosis is based more for general observations about their behavior; changes in quality, quantity, or color of feces; discharges; skin lesions; body odor; and so forth. [9] The same observations are used for pattern diagnosis in amphibians. After the pattern is identified, treatment is focused on correction of the excess or deficiency. The course of treatment is modified because the excess or deficiency changes.

Explanation of Acupuncture

While TCVM encompasses many different types of treatments, the most common type of treatment is acupuncture. Acupuncture works through acupoints, which are stimulated to have an effect on the nervous and circulatory system. The acupoints are located on meridians or channels that run throughout the body. Point selection is based on the pattern diagnosis and correcting the identified imbalance. The location of acupoints in exotic animals is not as well studied as it is in domestic animals. An experienced acupuncturist uses anatomic correlation between species to identify the possible locations of the acupoints. Careful palpation around those areas may reveal active acupoints, which are perceived as vague depressed areas. When those areas feel cool, it signifies a deficiency. When there is warmth, or areas that are raised and swollen, it signifies excess. [9]

Figure 1

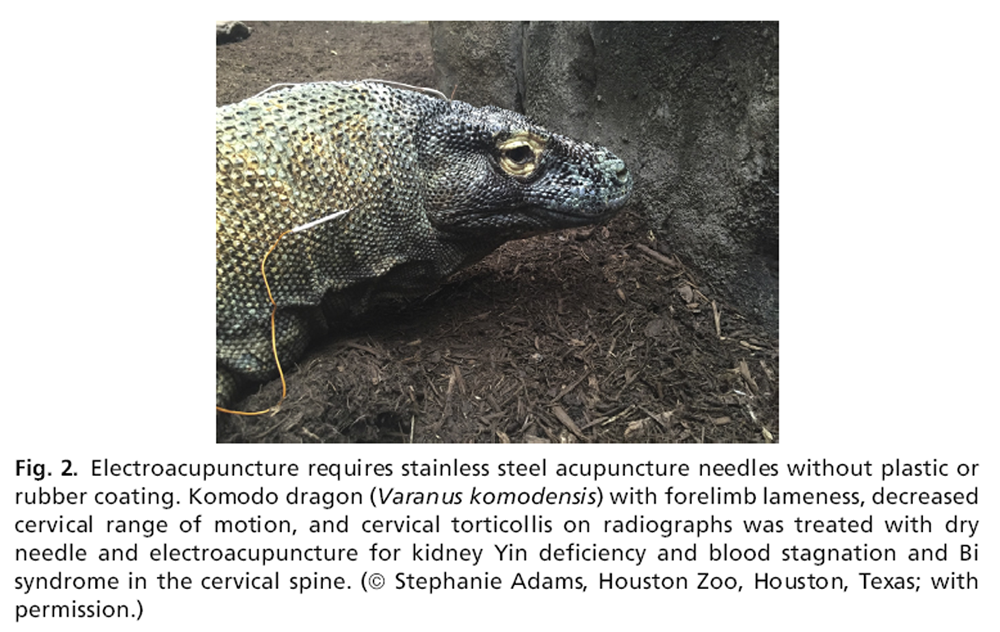

Figure 2

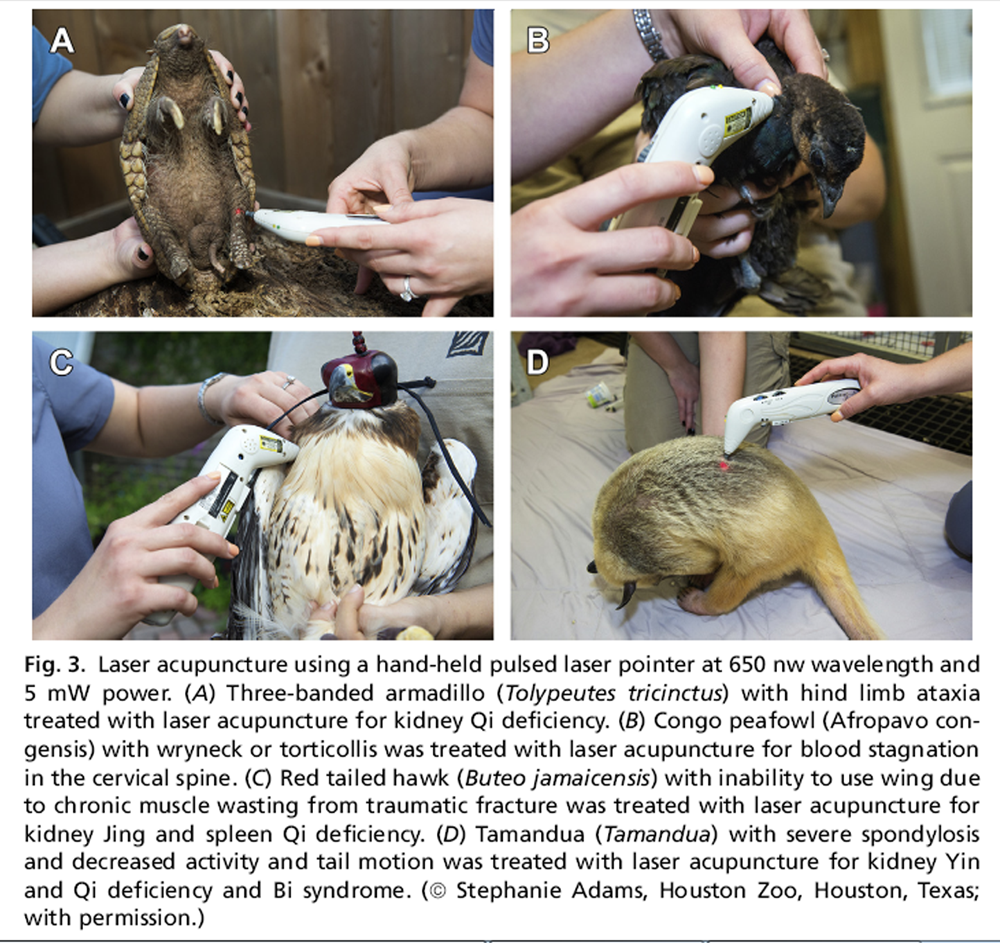

Figure 3

Table 2

Table 3 +

Table 4

Table 5 After the point is selected and located, it can be stimulated in a variety of ways. The classic method is using an acupuncture needle. This type of stimulation is termed dry needle acupuncture (Figure 1). These needles are malleable and range in thickness from 0.12 mm to 0.25 mm. Each needle requires a guide tube for placement because they will bend during insertion. This flexibility is important because muscle contraction in response to stimulation of the acupoint can bend and twist the needles. The needles can be used alone or can be stimulated with electrical current at frequencies based on the pattern being treated. This method is called electroacupuncture (Figure 2). Needles can also be stimulated with heated herbs, a process called moxibustion, which is useful in cases in which heat is needed in the body. In addition to dry needle acupuncture, hypodermic needles can be used to inject a substance, usually vitamin B12, into an acupoint. This method is termed aquapuncture. Injecting the patient’s own blood into an acupoint is termed hemopuncture.

Acupoints do not need to be stimulated by needles, they can also be stimulated with pressure, or acupressure. Laser can also be used to stimulate the acupoint [10, 11] (Figure 3). Acupressure and laser acupuncture have advantages in exotic animal patients that would not tolerate needle placement, cannot be touched, need to be handled in protected contact, or are at risk of needle placement depth, such as over the air sacs in birds. Laser acupuncture has an advantage over dry needle acupuncture because there is no perception of the needle entering the skin, it can be used without contact and even at a distance and also decreases acupoint stimulation time. [10, 12] Functional MRI studies in humans are being completed with laser acupuncture verses dry needles to eliminate any placebo effect from sensing needle placement. [11] Table 2 contains some examples of acupoints that are easily stimulated at a distance with laser acupuncture.

Explanation of Traditional Chinese Veterinary Medicine Food Therapy

Another approach TCVM practitioners use to restore their patients to a balanced state is food therapy. Sun Si Miao, a famous TCM practitioner from the Tang Dynasty (AD 618–907), said “dietary therapy should be the first step when one treats a disease. Only when this is unsuccessful should one try medicines. Without the knowledge of proper diet, it is hardly possible to enjoy good health.” [13]

Western nutritional principles rely on categorization into carbohydrates, fat, protein, vitamins, minerals, and trace elements. For TCVM, food therapy considers the energy, or thermal nature of the food, and uses the food as a form of treatment. [14] The most practical principle of TCVM food therapy to apply to exotic practice is using the thermal nature of the food to balance the Yin-Yang pattern. Feed cooling foods to patients who are overheated (Yin deficient) and warming foods to patients that are too cold (Yang deficient). Diet change in exotic medicine can be limited, but subtle application of TCVM food therapy can be straightforward and just as effective as herbal medicine. Tables 3–5 serve as general references for introducing TCVM food therapy into an exotic animal practice.

Explanation of Traditional Chinese Veterinary Medicine Herbal Therapy

Herbs should be treated like medications and only be used when assured of the patient’s pattern diagnosis. Herbs are not necessarily safe because they are natural. When the correct herb is chosen, it can be of great benefit to the patient. Because TCVM treats the individual patient and not a disease, it is not advisable to always use herb A to treat arthritis in a bird. In TCVM, arthritis in that bird may be due to several different TCVM pattern diagnoses. The bird could be Yin or Yang deficient. It could also have a Qi deficiency, kidney deficiency, and so forth. Each of these circumstances would call for a different herbal formula. Therefore, consultation with a Chinese herbalist is highly encouraged. In exotic medicine, it is even more difficult to give guidelines on herbs due to patient size, limited information on dosages, and differences in absorption. This is an area in which more studies are needed in exotic animals and domestic species. Herbal therapies also pose additional complications because the product consistency varies with growth cycles, harvest, storage, and processing practices, making them not as reliable as pharmaceuticals. It is also important to be sure that products are coming from a reputable company with ethically sourced herbs.

Cases That Could Benefit from Traditional Chinese Veterinary Medicine

TCVM has a wide scope of potential uses. Because TCVM is a complementary therapy, any TCVM treatment modalities can be used alongside Western treatments to enhance the Western therapy; decrease side effects; or, in some cases, prolong the need for Western therapy intervention.

TCVM can be used as preventative care in healthy patients. Patients that, based on species or breed, may be predisposed to conditions later in life can benefit from preventative TCVM therapies. Examples include supporting heart function in parrots and hedgehogs that are predisposed to cardiovascular disease, boosting the endocrine function of ferrets, and supporting renal and liver function across all species.

Box 1 TCVM can also be used for acute and chronic diseases that are being treated with or without Western medical therapies. In cases of acute emergencies, Western medicine provides a faster response. When stable, TCVM can be added to help complement the Western therapies. Additionally, there is an acupoint that can be stimulated to help with resuscitation. However, the author recommends that cardiopulmonary resuscitation be initiated first and the acupoint only be stimulated if there is an extra person who can do so without interfering with the resuscitation efforts (see Table 2). TCVM is also beneficial when there is no definitive diagnosis, cause, or course of treatment. A study performed by Brady and colleagues [15] found a positive response to treatment of owl monkey wasting disease (OMWD) using acupuncture with vitamin B12. Before this study, there was no known treatment of OMWD.

Examples of cases involving exotic animals treated with acupuncture are in Box 1.

Treatment Protocols

TCVM works to restore balance, which is a gradual process in the face of a chronic condition. The author recommends that owners commit to at least 5 treatments before making a decision on treatment effectiveness or assessing patient response. Treatments are typically spaced 1 to 2 weeks apart for most cases. For severe cases, there may be a need for 2 treatments a week. After the initial 3 to 5 treatments at 2 weeks apart, if the patient is responding, then the treatment intervals are gradually spread out to get to a maintenance treatment schedule of 3 to 4 times a year. If using TCVM to treat an acute illness, then only a few treatments may be necessary.

Side Effects, Precautions, and Contraindications

TCVM generally is considered safe with relatively few side effects. Acupuncture side effects include the release of endogenous endorphins that can cause patients to be sleepy or tired. In some cases, acupuncture temporarily worsens symptoms before gradual improvement. For exotic patients, there could be bruising around needle placement in thinner-skinned species and possibly soreness in the muscle from needle insertion. Side effects of using TCVM food therapy are gastrointestinal related. Herbal therapy can have varying side effects, depending on the potency of the herb.

Precautions should be taken when using acupuncture, especially on a new species in which the practitioner has no prior experience. A veterinarian experienced with the species should work closely with the acupuncturist to ensure that species variables are known, for the safety of both the patient and the acupuncturist. An acupuncturist also needs to understand the diet of the species before suggesting any changes for using TCVM food therapy.

Contraindications for TCVM food and herbal therapy include unknown source of herb or food, unknown pattern diagnosis, and unfamiliarity with species digestion and absorption. Considerations for acupuncture include avoiding certain points during pregnancy, avoiding points around a tumor, and not using acupuncture needles in open wounds. Electroacupuncture should be used with caution in the weak or debilitated patient or patients with history of seizures. Additionally, electrical leads should not cross the heart in a patient in poor cardiovascular health. [16]

INTRODUCTION TO CHIROPRACTIC

Chiropractic-type therapies can be traced back to multiple ancient civilizations, including Chinese, Roman, Greek, and Egyptian. Modern day chiropractic attributes its founding to D.D. Palmer, with Palmer School of Chiropractic being the first official training institution in the 1800s. Unlike TCVM, which seems to be more easily accepted by Western practitioners, chiropractic typically has more difficulty gaining broader acceptance. There is also frequently limited knowledge regarding the safety and education level of a trained chiropractor. Only 15% of people can correctly answer how much education is required to be a chiropractor. [17]

Chiropractic care in humans is widely requested. A Gallop poll from 2015 showed that over 50% of adults had sought chiropractic care at some point in their life. [17] Chiropractic care in animals may be sought out by those who have experienced chiropractic for themselves. Although well-intentioned, a problem can arise when these owners cannot find appropriate chiropractic care for their animals and seek treatment by laypersons or other underqualified practitioners.

Table 6 Dr Sharon Willoughby was a veterinarian who also became a doctor of chiropractic in order to apply it to companion animals. Her endeavors lead to the formation of the first animal chiropractic training courses in the late 1980s. Since that time, several schools have been established that train both human chiropractors and veterinarians in chiropractic care for animals. In most states, animal chiropractic must be performed by a licensed veterinarian or a licensed chiropractor. A licensed chiropractor needs written consent from the patient’s attending veterinarian before performing any animal chiropractic. Despite this legal requirement, there are still many lay people who inaccurately refer to themselves as animal chiropractors and who have caused injury to the animals and problems for the image of the profession. Clients seeking chiropractic for their animals, if not educated by their veterinarian about how to find a certified animal chiropractor or, for that matter, why they should, will often find a lay or untrained person to provide the treatment. Table 6 can be used to help seek certified animal chiropractors.

As with any new skill, a veterinarian should be properly trained in chiropractic techniques before providing these services to patients. The purpose of this article is to broadly educate the general practitioner regarding chiropractic, not necessarily to teach specific chiropractic techniques.

Explanation of Chiropractic

Dating back to ancient civilizations, with energy and balance as principles of health, chiropractic, like acupuncture, directly affects the circulatory and nervous systems. Most Western thinkers consider chiropractic relevant for only musculoskeletal type issues because that is the focus of most research and studies. This is a common misconception. The musculoskeletal component and influence of chiropractic on the body is profound. The impact on the nervous system is an overlooked benefit of chiropractic care and modern research has shown the imprint chiropractic can have on the body as a whole.

When describing chiropractic care, some of the confusion is due to terminology. The term chiropractic subluxation typically raises the most uncertainty. In Western training, a subluxation is a partial dislocation of a joint. A chiropractic subluxation refers to 2 adjacent joints that are lacking normal motion and/or alignment but are within the normal joint space. It is this lack of normal motion or alignment that causes interference with the nervous and circulatory system and, therefore, generates decreased function and pain. This is referred to as the vertebral subluxation complex (VSC). Modern advances in imaging have supported the VSC, which is now widely accepted and taught in chiropractic university training programs. VSC encompasses a variety of issues that can arise from a subluxation.

A trained chiropractic practitioner assesses a patient with the understanding of normal joint motion. A normal or healthy joint has a springy end feel and subluxated joints have a hard or restricted end feel when put through normal range of motion. Within the normal joint space, there are varying degrees of motion. Joints move through passive range of motion to active range of motion. At the end of the active range of motion of a joint there is an elastic barrier that stops the joint from going all the way to the end of its anatomic barrier. The chiropractic adjustment occurs in the space between the elastic barrier and the physical barrier to restore both passive and active range of motion.

To carry out the adjustment, the practitioner must know the directional plane in which the joint normally moves. This correct directional plane is determined by knowing the facet angle of the joint, which provides the practitioner the line of correction (LOC). The LOC is the guideline for the correction of the subluxation or the adjustment. Within a normal spine, the LOC changes with each segment and, in the case of the thoracic spine, it changes with each vertebra. A chiropractic practitioner can make adjustments in their LOC for each individual patient due to unique anatomic differences.

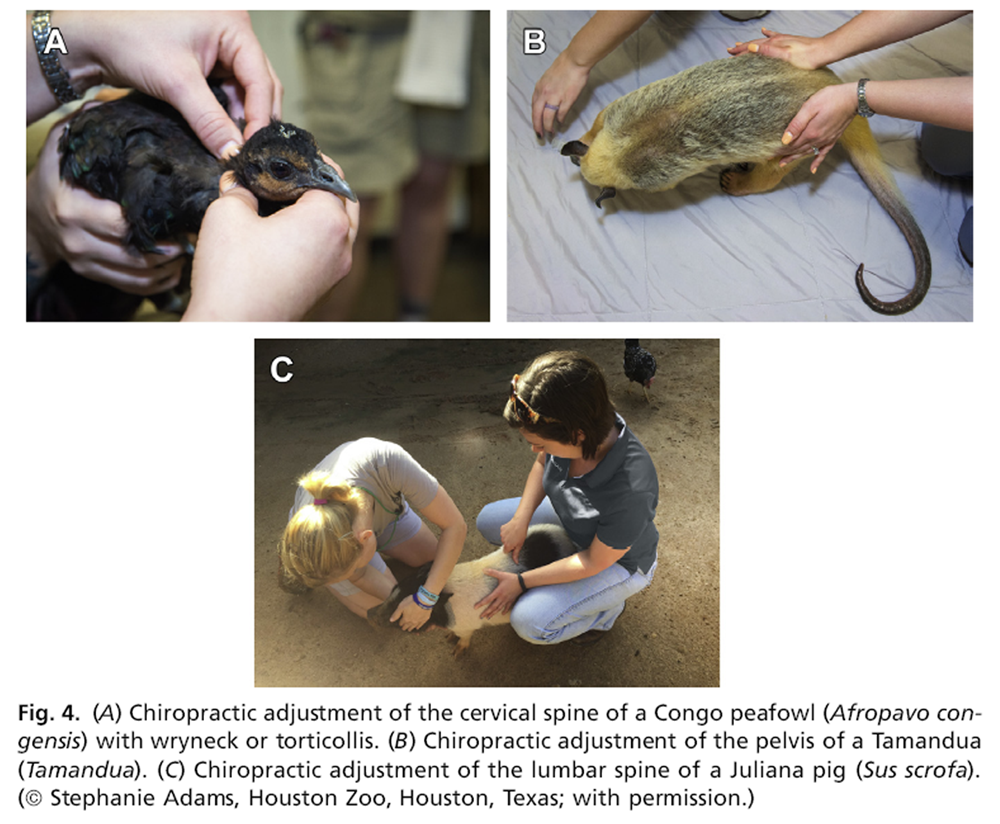

Figure 4 Recognizing differences in LOC within the same species will allow a practitioner to be more comfortable adapting to new species in which the practitioner has no prior experience. Training courses for animal chiropractic focus on the dog and horse. Extrapolating from those species, a skilled practitioner can move on to different species but only after becoming well-practiced and proficient (Figure 4). The size of smaller exotic species puts a premium on chiropractic finesse because the correction of the VSC does not stop at finding the LOC. After the LOC of the joint that is lacking normal motion is found, the adjustment is made by thrusting into the LOC. This thrust is a lowamplitude, high-velocity motion that, if not well practiced, could be particularly dangerous on a species in which the practitioner has no prior experience or training.

The thrust that makes the adjustment is usually performed manually; however, new adjustment devices in the human field are slowly being introduced to animal chiropractic techniques. [18]

Cases That Could Benefit from Chiropractic

The Journal of the American Medical Association published a study in 2017 that supports the use of spinal manipulative therapy as a first-line treatment of acute low back pain. [19] The American College of Physicians released new guidelines in 2017 that recommended spinal manipulation among the first-line of treatments for acute and chronic low back pain. [20] Acute and chronic low back pain cases have a high rate of positive response to chiropractic care in humans and in animals. However, for animals, chiropractic is not yet the first-line of treatment of back pain. Ettinger’s Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine lists exercise restriction and pain medication as treatments for back pain in animals. [21] More veterinary studies are needed to know if chronic back pain, spinal osteoarthritis, intervertebral disc degeneration, and advanced spondylosis could be prevented if chiropractic was introduced as an initial defense. Many clients are not waiting for these studies and are pursuing veterinary chiropractic on their own to potentially prevent these types of long-term issues.

Thirty-one percent of pet rabbits have vertebral column deformities and degenerative back lesions. [22] Chiropractic care can be initiated early in life to help prevent these issues by maintaining normal joint range of motion throughout the spine. Later in life, chiropractic can still be used to restore motion, even with an arthritic spine. Any motion that can be returned will help improve function. A series of animal experiments on nerve root compression found that only 10 mm Hg (which is about the weight of a dime) of compression on a nerve decreased the conduction of that nerve by 40% in the first 15 minutes and by 50% at 30 minutes. [23] Other studies have suggested this decrease in function to be 60% to 75%. After the compression is removed, recovery to near normal function occurred in 15 to 30 minutes.

Torticollis or wryneck has been documented in several species. In the human literature, there are many case reports of chiropractic improving or resolving torticollis. [24–29] In the veterinary literature, there is a case of successful management of acute-onset torticollis acquired during shipping in a 2-year-old giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis reticulate). [30] The author has also successfully treated wryneck in a Congo peafowl (Afropavo congensis) and numerous canines (Fig. 4A). After fractures are ruled out, any species with an abnormal neck position should be considered for chiropractic care.

Box 2 Nutritional deficiencies are common in exotic practice and several nutritional deficiencies can lead to joint inflammation. Examples include iguanas with metabolic bone disease and Guinea pigs with scurvy. [31] An inflamed joint can easily become fixated and lack normal motion. Once nutritional deficiencies have been treated, patients should be evaluated by a professional chiropractor.

>BR> Chiropractic can also be used as part of a preventative health care plan because it maintains a healthy nervous system and encourages normal gate patterns and weightbearing to decrease the likelihood of extremity injury and maximize overall performance. [32] Many human athletes attest long careers in part to chiropractic care as a key component of overall physical conditioning. National Football League players often receive chiropractic adjustments before, during, and after a game. [33]

Examples of cases involving exotic animals treated with chiropractic are given in Box 2.

Treatment Protocols

The recommended frequency of chiropractic adjustments depends on the condition, if it is acute or chronic, and if the goals are preventative or maintenance of a chronic condition. The recommended treatment frequency also varies between practitioners. For most cases, the author sees patients every 1 to 2 weeks for 2 to 3 treatments, in total. If the patient is responding well, then the time between treatments can gradually disperse to assess efficacy. Each situation is unique. One patient with spinal arthritis may walk better if adjusted every 4 weeks, whereas another may benefit with treatments every 12 weeks. Because the spine is constantly in motion and subject to strain, the author does not recommend longer than 4 to 6 months between adjustments. In acute cases, several adjustments may completely resolve the issue and ongoing chiropractic for that particular issue may no longer be needed. However, one must keep in mind that spinal nerve root compression can be present without causing the sensation of pain and, therefore, the absence of clinical signs. [34]

Side Effects, Precautions, and Contraindications

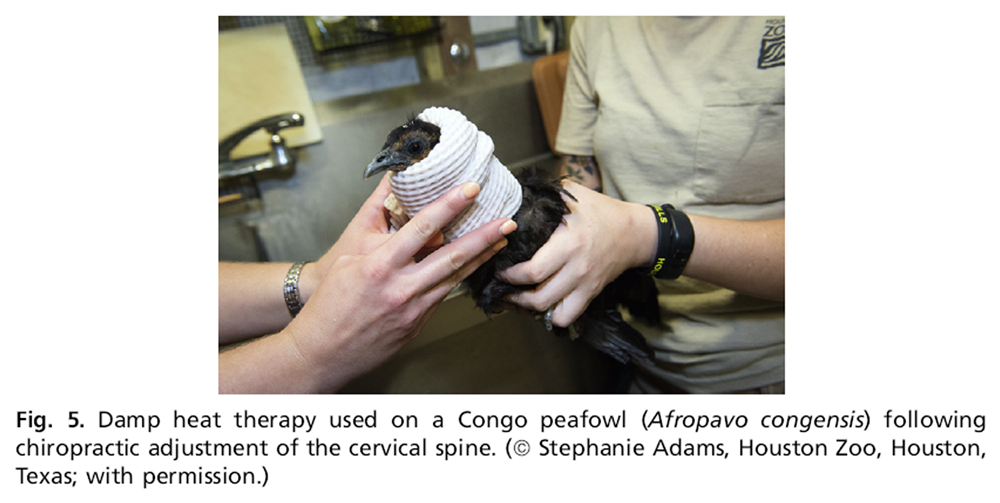

Figure 5 When used skillfully and appropriately, chiropractic therapy is safe and effective.35 The most common side effect to chiropractic is muscular soreness. Changing the way that the joint moves also changes the muscles engagement. This muscle soreness is similar to a new workout routine when muscles are stressed beyond typical restful conditions. Some patients are noticeably sore 24 to 48 hours after their first adjustment, whereas other patients do not show any signs of soreness. In the author’s experience, patients that do exhibit soreness do so for only 24 to 48 hours and generally do not require any medical intervention. Using damp or moist heat therapy over sore, tight muscles will help a patient improve faster and provide relief (Figure 5). Damp heat also prevents the drying effect on skin and muscles that can come from dry heat therapy. To apply damp heat, a moist warm towel is used. To increase duration of treatment a heating pad or hot rice bag maybe added.

Precautions should be made whenever undertaking treatment on a new species. Having an understanding of species anatomy and normal motion is important. It is difficult to assess abnormal motion without a baseline definition of normal motion. Chiropractors (DC or DVMs) who are not familiar with particular exotic species should be assisted by an experienced exotic veterinarian. This helps to ensure the safety of the patient as well as the practitioner, who may not be aware of the dangers of working with certain exotic species.

Chiropractic is contraindicated if there is a history of trauma or disease in which bone integrity could be compromised. This case history could include fractures, congenital anomalies, acute infections (eg, osteomyelitis and septic discs), spinal tumors or malignancies, dislocation of vertebra, internal fixation or stabilization devices, and other diseases causing instability of the spine.35 In cases of focal spine lesions, a chiropractic adjustment may still be performed on other areas of the spine.

SUMMARY

Studies on applying nontraditional therapies in exotic animal practice are very limited. However, the research being done in the human and companion animal fields support the safe application of nontraditional therapies into exotic animal practice.

Integrating nontraditional therapies into general practice requires advanced training and skills. Attending an advanced training course or coordinating with a practitioner who is already trained in nontraditional therapies will provide a practitioner additional tools to complement Western therapies and work together toward the goal of prevention and relief of animal suffering.

References:

Model Veterinary Practice Act July 2017. Available at:

https://www.avma.org/KB/Policies/Pages/Model-Veterinary-Practice-Act.aspx

Accessed November 28, 2017.Barnes, PM and Bloom, BS.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Adults and Children: United States, 2007

US Department of Health and Human Services,

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD, 2008.Meredith K, Bolwell CF, Rogers CW, et al.

The use of allied health therapies on competition horses in the North Island of New Zealand.

N Z Vet J 2011;59(3): 123–7.Xie H. Preface. In: Xie H, Preast V, editors.

Xie’s veterinary acupuncture.

Ames (IA): Blackwell Publishing; 2007. p. xi–xiii.Conference Proceedings: Pacific Veterinary Conference:

PacVet 2015. Peter G. Fisher

“Exotic Mammal Geriatrics”.

Available at:

http://www.vin.com/members/cms/project/defaultadv1.aspx?id56789820&pid511768 11/26

Accessed November 16, 2017.Xie H.

How to start traditional Chinese veterinary medicine in exotic animal practice.

In: Xie H, Trevisanello L, editors.

Application of traditional Chinese veterinary medicine in exotic animals.

Reddick(FL): Jing Tang Publishing; 2011. p. 3–28.Xie H. Zang-Fu physiology.

Traditional Chinese veterinary medicine fundamental principles, vol. 1.

Reddick(FL): Chi Institute; 2007. p. 105–48.West C.

TCVM for avian species: introduction, general overview, acupuncture point locations,

indications and techniques.

In: Xie H, Trevisanello L, editors.

Application of traditional Chinese veterinary medicine in exotic animals.

Reddick( FL): Jing Tang Publishing; 2011. p. 53–72.Eckermann-Ross C.

Traditional Chinese veterinary medicine in reptiles.

In: Xie H, Trevisanello L, editors.

Application of traditional Chinese veterinary medicine in exotic animals.

Reddick(FL): Jing Tang Publishing; 2011. p. 159–92.Law D, McDonough S, Bleakley C, et al.

Laser acupuncture for treating musculoskeletal pain: a systemic review with meta-analysis.

J Acupunct Meridian Stud 2015;8(1):2–16.Quah-Smith I, Sachdev PS, Wen W, et al.

The brain effects of laser acupuncture in healthy individuals: an fMRI investigation.

PLoS One 2010;5(9):e12619.Petermann U.

The components of the pulse controlled laser acupuncture.

American Journal of TCVM 2012;7(1):57–67.Kastner J. Theory.

Chinese Nutritional Therapy Dietetics in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM).

2nd edition. New York: Thieme; 2009.

Kindle edition Chapter 1, section 5, paragraph 10–11.Kastner J. Theory.

Chinese Nutritional Therapy Dietetics in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). 2nd edition.

New York: Thieme; 2009.

Kindle edition Chapter 1, section 7, paragraph 1–2.Brady A, Wilkerson G, Williams L, et al.

Characterization and treatment of a new wasting disease of owl monkeys (Aotus sp.).

In: Joint AAZV/EAZWV/IZW Conference Proceedings, Atlanta (GA), July 16–22, 2016.Xie H.

General rules of acupuncture therapy. In: Xie H, Preast V, editors.

Xie’s veterinary acupuncture.

Ames(IA): Blackwell Publishing; 2007. p. P245–6.Daly J.

Gallup-Palmer College of Chiropractic Inaugural Report: American’s Perception of Chiropractic. 2015.

http://www.palmer.edu/uploadedFiles/Pages/Alumni/gallup-report-palmer-college.pdf

Accessed November 29, 2017.Duarte FC, Kolberg C, Barros RR, et al.

Evaluation of peak force of a manually operated chiropractic adjusting instrument with an adapter for use in animals.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2014;37(4):236–41.Paige NM, Miake-Lye IM, Booth MS, et al.

Association of spinal manipulative therapy with clinical benefit and harm for acute low back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis.

JAMA 2017;317(14):1451–60.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al.

Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians.

Ann Intern Med 2017;166(7):514.LeCouteur R, Grandy J.

Diseases of the spinal cord.

In: Ettinger S, Feldman E, editors.

Textbook of veterinary internal medicine. 6th edition.

St Louis (MO): Elsevier Sanders; 2005. p. 871.Makitaipale J, Harcourt-Brown FM, Laitinen-Vapaavuori O.

Health survey of 167 pet rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) in Finland.

Vet Rec 2015;177(16):418.Sharpless SK.

Susceptibility of spinal roots to compression block.

In: Goldstein M, editor.

The Research Status of Spinal Manipulative Therapy.

Bethesda (MD): HEW/NINCDS Monograph #15; 1975. p. 976–98.Hobaek Siegnthaler M.

Unresolved congenital torticollis and its consequences: a report of 2 cases.

J Chiropr Med 2017;16(3):257–61.Hobaek Siegnthaler M.

Chiropractic management of infantile torticollis with associated abnormal fixation of one eye: a case report.

J Chiropr Med 2015;14(1): 51–6.Kaufman R.

Co-management and collaborative care of a 20-year-old female with acute viral torticollis.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2009;32(2):160–5.McWilliams JE, Gloar CD.

Chiropractic care of a six-year-old child with congenital torticollis.

J Chiropr Med 2006;5(2):65–8.Kukurin GW.

Reduction of cervical dystonia after an extended course of chiropractic manipulation: a case report.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2004;27(6): 421–6.Toto BJ.

Chiropractic correction of congenital muscular torticollis.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1993;16(8):556–9.Dadone LI, Haussler KK, Brown G, et al.

Successful management of acute-onset torticollis in a giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis reticulata).

J Zoo Wildl Med 2013; 44(1):181–5.Ness R.

Chiropractic care for exotic pets.

Exotic DVM 2000;2(1):15–8.Lowell D.

Use of chiropractic for therapy and prevention of disease.

In: Western Veterinary Conference Proceedings. 2003. Available at:

http://www.vin.com/members/cms/project/defaultadv1.aspx?id53846900&pid511155

Accessed December 11, 2017.Chiropractic in the NFL.

In: Professional Football Chiropractic Society. Available at:

http://profootballchiros.com/chiropractic-in-the-nfl/

Accessed December 1, 2017.Hause M.

Pain and the nerve root.

Spine 1993;18(14):2053.World Health Organization (WHO)

Guidelines on Basic Training and Safety in Chiropractic

Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; November 2005

Return to ACUPUNCTURE

Since 4-22-2018

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |