Inclusion of a CAM Therapy (Chiropractic Care) for the Management

of Musculoskeletal Pain in an Integrative, Inner City,

Hospital-based Primary Care SettingThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Alternative Medicine Research 2010 (Dec); 2 (1) 61–74 ~ FULL TEXT

Deborah Kopansky-Giles, BPHE, DC, Howard Vernon, DC, PhD, Heather Boon, PhD, Igor Steiman, MSc, DC, Maureen Kelly, BScN, MPA and Natasha Kachan, MEd

St Michael‘s Hospital,

University of Toronto,

Toronto, Canada

Musculoskeletal (MSK) pain, in particular low-back and neck pain, is an ubiquitous societal problem with high economic costs. While the provision of care to people suffering from MSK conditions has traditionally been delivered by separate practitioners, there has been recent interest in new models of care delivery that promote team-based or integrative care.

Objectives: Our project undertook the novel inclusion of a complementary and alternative therapy (CAM) – chiropractic – in a hospital environment.

Study Group: All adult patients referred to the chiropractic program were eligible to participate as long as they had English language proficiency.

Methods: The study utilized a mixed-methods approach which employed an ethnographic qualitative research design using interview-based data and semi-structured, in-depth interviews, as well as survey instruments and a specific clinical outcomes protocol.

Results: Successful integration of the chiropractic services was accomplished. Both patients and providers reported very high levels of satisfaction with the inclusion of the services. Clinically important improvements in levels of pain and disability were obtained for all complaint categories.

Conclusions: The success of this integration study has resulted in the chiropractic services being maintained as a permanent service in the hospital. Chiropractic treatment appears to be a useful adjunct in the management of MSK pain conditions, even in highly systematized settings of primary care hospital clinics and for clinically complex and marginalized populations.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Low-back pain and neck pain are nearly ubiquitous in Western societies. Bergennud and Nilsson [1] reported a lifetime prevalence of back pain as 75–90% with a point prevalence of 18–29%, while 5% of the population is disabled from back pain at any point in time. Similarly, the lifetime prevalence of neck pain is 67% with a point prevalence of 22%; with disabling neck pain occurring in 4.6% of the population. [2] The costs associated with the management of back pain alone have increased by 65% over the past decade, making this condition a highly significant social concern. [3] These findings are similar in adults experiencing neck pain. [3]

While these musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions may be self-limiting and respond to conservative treatment, approximately 10–15% of patients go on to develop chronicity. [2] This makes early identification of non-specific neck pain and low-back pain (LBP), and early provision of appropriate care to best utilize limited health resources, very important.

The problems noted above become even more pressing when considering how they manifest in poor and marginalized communities such as inner city populations. These populations have distinctive health needs arising from the complexity of their personal and social circumstances. Issues such as poverty, under-housing, limited access to, and affordability of health services and the proliferation of chronic diseases have an enormous effect on the lives of these people and their families. [4] Many of them do not have access to a family physician and will seek care in emergency departments which involve long wait periods for the patient and are prohibitively expensive for the system.

Glazier et al [4] and Wasylenski [5] have described the complexity of socioeconomic and health issues facing inner city communities. In a major urban center in Canada Toronto, Ontario) St Michael‘s Hospital (SMH) serves as an urban academic health science centre in the city‘s inner core. Statistics from Metropolitan Toronto confirm that the neighbourhoods served by SMH are among the poorest in the city. [6]

In 2003, the SMH initiated a program to improve the care for musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions that it offered to this poorer community, one which historically has had very limited access to early health intervention and minimal access to a broader range of clinical services, such as CAM therapies. Hospital administrators determined that there was strong community interest in obtaining a previously non-included complementary/alternative medicine service – chiropractic – at the hospital. They determined that there were no other health professionals providing manipulative therapy in the hospital and that there was strong evidence to support chiropractic treatment of MSK conditions.

The integration of CAM services into mainstream medicine has become an area of increasing interest for health care providers, the public, health care institutions and policy makers over the past decade. [7–10] This trend is influenced by the increasing utilization of CAM by the public in the developed world. Reports from the United States [11–14], Australia [15], the United Kingdom [16], and Canada [17] indicated that the use of CAM therapies and products had grown considerably, almost surpassing the use of conventional medicine in these countries. According to Tindle et al [12], this trend remained steady up to 2002. In these utilization studies, chiropractic care is consistently ranked as one of the top three CAM therapies accessed by the public. [13, 15, 17]

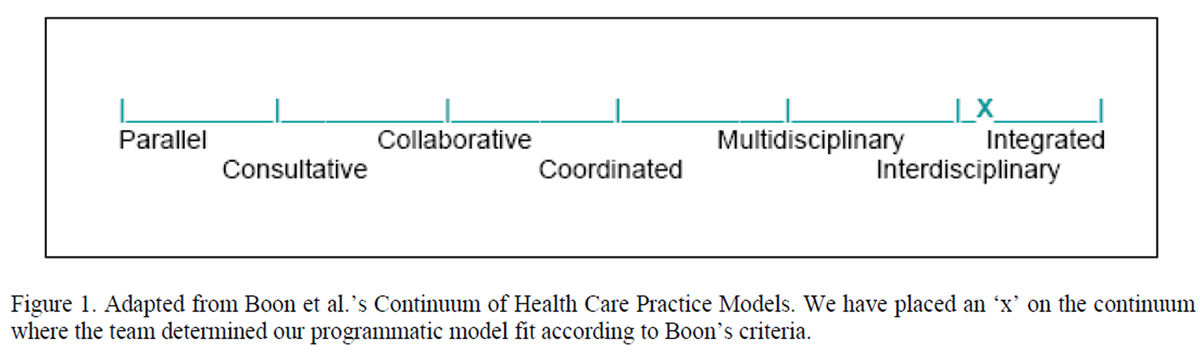

With the increasing emphasis on integrated health service delivery, much interest has been directed towards evaluating how successful integration models are developed and achieved. Boon and her colleagues [18] detailed the characteristics of integrative care and offered a framework for determining the level of integration of a particular program of care. One end of the continuum described in this framework represents programs that fully realize integrative care. This framework was utilized as a reference point for the evaluation of the level of integration that was achieved in this study.

In collaboration with the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College (CMCC) a grant for this project was obtained from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care. This project was designed as a prospective observational study with three main aims:

To evaluate whether a CAM therapy, (chiropractic), that was not previously available in the hospital, could be integrated successfully within a hospital system of care and whether this inclusion would result in a high utilization of the services for individuals suffering with musculoskeletal pain. (model development).

To evaluate whether the newly introduced services were effective in reducing or alleviating musculoskeletal pain and related disability (clinical outcomes).

To evaluate the level of satisfaction of patients and collaborating providers/administrators with the model of care and the sustainability of such a model (satisfaction and sustainability).

Methods

Model developmentService integration: The development of the clinical service and the model of service integration were undertaken by an interdisciplinary working group. This group was composed of physicians, chiropractors, physiotherapists, clinical managers, administrators and employee health representatives. The working group‘s responsibility was to determine how the chiropractic services would be integrated into the Department of Family and Community Medicine (DFCM) and how communication within the department could be improved to transition towards a team-based care model. The tasks of the working group included defining scope of services, triage and referral processes, access to diagnostic imaging, reporting structures and creating electronic medical chart templates shared by chiropractic and physiotherapy. Inclusion of chiropractors on other hospital-wide committees and as educators within the department was also facilitated by this group.

The evaluation of the model development was conducted by a team of researchers from the University of Toronto that employed an applied ethnographic qualitative research design using interview-based data. [19] Semi-structured, in-depth interviews [20] were conducted over a period of 2.5 years with departmental chiropractors, physiotherapists, physicians, nurses and administrators.

Most participants were interviewed at least twice during the study. All interviews were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were then analyzed for main themes using basic content analysis [21, 22] and entered into the qualitative software program Nvivo 2.0 for further analysis. The researchers also observed working group and team meetings over the two years of the study.

Interventions: Chiropractic services were provided within an evidence-based, patient-centered model. Two chiropractors managed patients with musculoskeletal problems who were referred to the clinic. Clinical management included comprehensive initial examination, use of diagnostic imaging if necessary, provision of manual treatment (spinal and joint manipulation, mobilization, soft tissue therapy), physiological modalities, education, exercise prescription, lifestyle counselling, and interactive assessment. Referral notes were provided to the physicians after intake and discharge notes were provided on treatment cessation.

Clinical efficacyProtocol development: Team members, including chiropractors, physicians and administrators, worked together to develop a set of project outcome measures by conducting literature reviews, by collaborating with two other integration projects and by team evaluations of the value and the practicality of a variety of measures. Existing computer-based combinations of such measures were also reviewed. Permissions for use of the selected instruments were obtained. Copies were collated into a package for every patient.

Table 1 The final outcomes instrument package (see table 1) consisted of a variety of self-report outcome instruments measuring pain severity, physical disability – region specific, physical disability – patient specific, physical disability – general and quality of life, at intake and discharge, as well as two instruments for self-rated improvement and satisfaction at discharge. These domains are consistent with those highlighted by Verhoef and her colleagues [23, 24] with respect to assessing the benefit of integrated care.

Outcome measures

Numerical rating scale (NRS)-101: The Numerical Rating Scales (NRS)-101 [25] were used to assess average or typical lower back, neck or other region pain experienced by patients on a 101–point scale, where 0 was "no pain" and 100 was "worst pain". Patients also reported their current pain on the same scale and the overall percentage of their "awake time", where their pain was "at its best" and "at its worst". The NRS-101 has been validated as a reliable pain intensity assessment scale. Farrar et al [26] have reported that a 20 mm or greater improvement in these types of pain scales is regarded as clinically important.

Neck disability index (NDI): The NDI [27] is a validated instrument [27, 28] used for self-assessment of disability due to neck pain using ten dimensions of disability related to:pain intensity,

impact of pain on personal care,

lifting,

reading,

headaches,

concentration,

work,

driving,

sleeping, and

recreation.According to Riddle and Stratford [29], a 5–point decrease in NDI scores (out of 50) represents a clinically important change.

The Roland-Morris low back pain and disability questionnaire (RMQ): The RMQ [30, 31] is widely used and is one of the most frequently studied pain measures applied to populations with low-back pain. [32, 33] The 24–item scale covers a variety of activities of daily living originally taken from the Sickness Impact Profile (SIP). As has been done in previous studies, we added "because of my back" to a number of items to improve response specificity. [34] Respondents check each item to respond affirmatively to the statement. Checked items receive a score of 1. Scores can therefore vary from 0 (no apparent disability) to 24 (severe disability).

For the RMQ, both the minimal detectable change (MDC, defined as the minimal amount of change required to be confident that the patient has truly changed at follow-up or discharge) and the minimal clinically important differences (MCID, defined as the smallest change that is important to patients) have been reported to vary between two and five change points. [34–36] Stratford and colleagues [36] suggested that both MDC and MCID at five change points were dependent on the initial assessment and applicable mainly to patients scoring in the mid-range of the scale. A smaller change point is apt to denote change applicable for patients who initially scored on the extremes of the scale. We therefore used a global rating range for improvement between 3 and 5 to assess patient change from intake to discharge.

SF12-Version 2: The twelve-item Short Form Survey (SF12.v2) [37] was used to provide physical (PCS 12) and mental (MCS 12) health summary scores using a standard four- week recall period. The instrument has been demonstrated in clinical and population-based applications to be valid and reliable in numerous countries. [37–40]

Measure yourself medical outcome profile (MYMOP): The MYMOP [41, 42] consists of four items with an acute recall period of one week designed to measure in-person change over time. The scale consists of two patient-identified "symptoms of importance" and a self-identified "activity" that the patient considers has been adversely affected – "made difficult or prevents from doing" – by the presenting problem. These items are ranked on a seven-point scale from 0– "as good as it can be" to 6 – "as bad as it could be". The fourth item rates general feeling of well-being on the same scale. Duration of symptom 1, utilization and dosage of medication in treatment of symptom 1, and attitudes toward medication are also included on the MYMOP instrument. The follow-up MYMOP consists of the same four items, medication usage and an added item for patients to identify any new symptom which may have emerged since intake.

Paterson [43] reported average improvements of 1.44/7 points in a cohort of patients treated with CAM therapies in a British general practitioner‘s practice. Paterson reported that 0.5 points represents a minimal clinically important change (MCID) on this instrument.

Self-assessed pain relief and activity increase

At discharge we were interested in having patients provide a global assessment of the pain relief and activity increase they may have experienced since intake. We asked respondents to recall the first day of their rehabilitation program and report on a 10–point scale, where 1 was "no pain relief" or "no increase in activity" since intake, and 10 was "complete relief of pain since the program began" or "complete recovery of all activity since program began".

Inclusion criteria

Patients were eligible for the "outcomes study" if they were referred to the Chiropractic Clinic by a St. Michael‘s Hospital family physician, through the Positive Care Clinic (for HIV/AIDS) or through the Employee Health Unit. Subjects were over the age of 18 and had English language proficiency. Eligible patients provided informed consent for participation in the study at intake, completing the instrument package prior to their first treatment and information session, and again at discharge from the clinic. Subjects were informed that declining to participate in the outcomes study would not affect their care in any way. Orientation on the correct completion of the instruments was provided to the patients by clinic staff at the intake visit.

Data collection

Ethics approval from the SMH and CMCC required approximately nine months for completion. Prospective data collection began June 1, 2005. Once ethics approval was obtained, data were also collected retrospectively from files; as such, this report represents a two-year follow-up. Data were entered into a custom-made computer database (Ontario Chiropractic Association – Patient Management Program: modified ©). This program was also used by two other large-scale primary care integration studies [44], [Mior S, personal communication].

Age, gender, clinical category and duration of complaint were extracted from the patient intake form. Education level, employment status and income variables were not collected. Demographic and outcomes data were first entered into the PMP by clinic staff and then transferred to an SPSS database. All data were subsequently analyzed using SPSS version 11. As this was an observational study on a selected patient sample, no statistical testing of the outcomes was conducted. Rather, effect sizes were calculated for measures with pre-post data in order to evaluate the magnitude of changes in these measures. The mean change scores in these measures were compared to published benchmarks as noted above.

The team also tracked the incidence of adverse events occurring with the provision of chiropractic care. The WHO (2005) definition as follows was utilized:"an injury related to medical management, in contrast to complications of disease. Medical management includes all aspects of care, including diagnosis and treatment, failure to diagnose or treat, and the systems and equipment used to deliver care. Adverse events may be preventable or non-preventable"? [45]

Patient and provider satisfaction and sustainability

All patients attending for chiropractic treatment who were able to provide informed consent were included in the project. A 20–item survey was developed to examine patient satisfaction with the chiropractic clinic and clinic practitioners. The survey included eighteen items measured with a five-point scale (excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor), adapted from a patient satisfaction questionnaire developed by the Ontario Workplace Safety and Insurance Board [46] to assess administrative experience with the clinic, overall care, quality of the educational resources provided, waiting time, and aspects relating to the quality of care provided by the chiropractor. The remaining two items inquired about intent to return to the clinic if future care was needed and likelihood of recommending the clinic to others, measured on a four-point scale where 4 was "definitely would" and 1 was "definitely would not". A physician satisfaction questionnaire was also created using a modified 7–point Likert scale. This was a five-part questionnaire divided into the following sections: recalling one‘s expectations of the collaboration with the chiropractors, and measuring one‘s current expectations of the collaboration with the chiropractors, one‘s attitudes and perspectives regarding chiropractic, one‘s attitudes and perspectives about the chiropractic services within the department, and general demographic information about the respondent.

Results

In 2004, the hospital‘s Department of Family and Community Medicine (DFCM) began the provision of chiropractic care. Data collection occurred between July 2004 and mid-September 2006. Successful integration of chiropractors into the DFCM at SMH did occur. Within the study period, essentially all physicians (n = 45) in the department referred to the program over its duration, and there was high utilization of the services by patients. Within a 6–month period there was a 4 to 6 week wait to access care. Physicians initially referred for low-back pain however, over the course of the first year the trending of referrals demonstrated that they were referring to the chiropractors for essentially all types of MSK conditions.

The chiropractic clinic (CC) was located in the same building as the main family practice clinic in the DFCM (there are four clinical sites for family practice in the DFCM). The CC consisted of facilities shared with the existing physiotherapy clinic. Waiting room and front office space were shared; two treatment rooms were dedicated to chiropractic treatment and were equipped accordingly. The space was renovated over a period of six months to more appropriately house the shared space, to improve patient flow and to promote collaboration. Social workers and dieticians shared the joint reception and waiting room area as well. Juxtaposing these services facilitated increased communication amongst providers and a stronger team-based approach to care by improving personal relationships between the department health professionals.

Patients were able to access the chiropractic services on referral from one of three sources: family physicians in the DFCM, physicians in the Positive Care Clinic (a clinic devoted to serving people living with HIV/AIDS), and through the SMH Corporate Health and Safety program (CHS). To increase physician awareness of the service and understanding of chiropractic care, an educational outreach program was implemented. The outreach program aimed to inform physicians and other staff about the presence of the CC and included medical rounds sessions on the evidence-based outcomes associated with chiropractic treatment of low-back pain in particular, and other chronic musculoskeletal pain syndromes. Additionally, incoming medical residents were provided with an integrated case education session which involved the chiropractors on the case faculty. The clinical interaction among the chiropractors, physiotherapists and physicians, along with the administrative processes undertaken to establish the clinic and the staff credentialing occurred within standing working groups (for example, the Clinical Working Group, the Interprofessional Education Working Group) of the department and through inclusion of the chiropractors on hospital-wide committees (for example, the Health Disciplines Advisory Committee).

Model development

Semi-structured, in-depth interviews were conducted from February 2004 (prior to program start) – August 2006 with 18 key participants (4 administrators, 2 chiropractors, 2 physiotherapists and 10 family physicians). All interviews included questions about perceptions of, and involvement in, the integration of chiropractic services at SMH. All participants were interviewed at least twice, with the exception of two administrators and three family physicians who were only interviewed once. A total of 42 interviews were conducted.

Three main themes were identified in the interview data that related to the integrative service that evolved during the study. They were:

Success Factors

Barriers

Outcomes.

Success factors

This theme encompassed the perceptions of respondents regarding the factors that contributed to the success of the integration of chiropractic at SMH. These included the importance of "champions", laying groundwork, the culture at SMH, and the choice of practitioners.Champions: Many respondents highlighted the importance of key players who championed this program. There was a widespread opinion that without these champions, the program would not exist. Respondents recognized that a potentially controversial program such as this one required its proponents to be stellar in terms of their personal and professional credibility. "Credible" champions were identified as one of the key success factors for this program.

Laying the groundwork: One of the keys to the success of the chiropractic integration project was the fact that a considerable amount of energy was dedicated to gradually introducing the program to other departments at SMH long before its actual launch. This groundwork ensured that by the time the program came into existence, other departments were prepared for it and were not threatened by the introduction of a new service that they perceived might result in competition for resources. Through the preliminary work, the key players were able to convey that this program was supported by senior level administration, which in turn sent the message to physicians that the chiropractic service could serve as a safe, legitimate option for treating their patients.

Organizational culture: According to respondents, because SMH is unique in terms of its philosophy and the patient population it serves, it is more amenable to the implementation of treatment programs that fall outside the sphere of traditional Western medicine. Many respondents implied that the culture of SMH was an important factor in the success of this program.

Choice of practitioners: Many physicians identified that the chiropractors at SMH were chosen for their level of expertise and experience and that this was an important factor as to whether or not they were likely to refer to the service. Respondents referred to the "legitimacy" lent to the chiropractors because they were selected to work in the hospital setting. The high quality of the referral notes and positive patient feedback was also highlighted by the physicians when discussing why they felt comfortable referring to the service. Physicians reported that they felt reassured by the high level of expertise of the chiropractors and indicated that the integration of the service alleviated their workload somewhat with respect to return patient visits for MSK conditions.

Barriers

This theme encompassed those items identified by respondents as potentially hindering the success of the chiropractic program. These included: funding, lack of awareness of the service and perceptions of risk.

Administrators, staff, and physicians directly involved with the chiropractic initiative repeatedly identified the lack of a viable, permanent source of funding as the only barrier they saw in the long-term continuation of the program. In the shorter term, referrals were a key to the success of the program. Physicians with both high and low referral rates to the chiropractic service were asked to speculate why their colleagues might not refer to the chiropractic service. Referring physicians hypothesized that physicians who were not referring likely did not know that the service existed as some physicians flowed in and out of the department depending on their residency program. Finally, perceived risk of certain aspects of chiropractic treatment was also mentioned as a barrier. Some thought it may limit the number and kinds of referrals from physicians.

Outcomes

While this qualitative component of the project was not designed to objectively assess the clinical outcomes of the integration project, many participants talked about their perceptions of improved patient care and access to care. The long wait period for physiotherapy was also anecdotally noted to have been reduced in the first six months of program delivery. In addition, several new educational approaches for family medicine residents and other interprofessional health science students were developed and implemented over the two-year period as well as a collaborative patient education initiative delivered by the physiotherapists and chiropractors, all which were felt to be important by respondents.

Clinical outcomes

Table 2 A total of 443 patients (99.6% of patients receiving care at the CC) were enrolled in the outcome study (F = 275, M = 168). The average age of the patients was 48.5 (14.1) years with a range from 20–85 years. Eighteen percent (18%) of patients were aged 19–35 years and 14% were above age 65 years. Seventy-eight per cent of our patients came from the two poorest neighbourhoods in the city (Regent Park and Moss Park). Eighty percent (80%) of patients were categorized as either chronic (65.5%) or recurrent (14.5%) in their clinical presentation, while 20% were considered as acute in their clinical presentation. The predominance of chronic cases occurred over all diagnostic categories as shown in Table 2. A total of 6,261 treatment visits were provided during the 26 reference months, for an average of 14 per patient. Table 2 presents the clinical data on referral source and area of chief complaint.

The majority of referrals came from physicians of the DFCM. Table 2 shows that a small minority of referrals came from physicians working in the Positive Care Clinic for HIV/AIDS, while a slightly larger number of referrals came from the CHS program. The majority of the latter referrals were nurses suffering injuries in the workplace. In the DFCM, the majority of referrals came from physicians who were housed in the main family practice site, where the chiropractors were co-located.

All patients who consented to participate provided initial outcomes data, depending on the area of complaint. Fewer patients completed the outcomes instruments at discharge; the rate of completion varied among the instruments.

Outcomes instruments

Table 3 This report will present the primary data (i.e., total scores) from each of the instruments. The results are displayed in Table 3.

NRS-101: Low Back and Neck pain: The mean changes in pain intensity (NRS-101 scores) obtained in the cohort of low-back pain patients of 2.8 (3.1) and of neck pain patients of 3.1 (2.5) exceeds the clinically important level of 2.0 (26) and represents a large effect size (0.83) and (0.86) respectively.

Other pain: The mean change in pain intensity (NRS-101 scores) obtained in the cohort of "other pain" patients of 3.5 (2.8) exceeds the clinically important level of 2.0, although it represents only a medium effect size (0.46).Roland-Morris Low Back Pain Questionnaire: Change scores were calculated from 46 completed pairs of questionnaires. The mean change was 5.1 (out of 24).

Table 4 Table 4 shows the percentage of these patients achieving worsening, 0 change, and 3–point, 4–point and 5 >–point change, with a 5–point change being at or above the minimal clinically important change, as noted above.

Neck Disability Index: The mean change in the NDI scores of the cohort of neck pain patients of 13.1 (11.7) exceeds the clinically important level of 5 points [30], although it represents only a medium effect size (0.56). This is likely due to the small sample available for this measure.

MYMOP: The changes in the MYMOP scores for patients' all complaint categories exceeded the clinically important level of 2, and represented large effect sizes (1.03 – 1.35).

SF-12: For our study population, the mean baseline Physical Health composite score appeared somewhat lower than the US age-related average (39). The mean baseline Mental Health composite score appears to match the US age-related average. Change scores in the Physical Health composite were greater than those of the Mental Health composite, with neither composite demonstrating a clinically important change.

Adverse events: As shown in Table 2, there were no serious adverse events.

Self-assessed improvement: Patient self-assessed improvement in pain and activity levels achieved high scores of 7.5 (2.4) and 7.2 (2.4), respectively. The average "pain relief" score (out of 10) was 7.5 (2.4); the average score for "activity increase" was 7.2 (2.5).

In summary, clinically important improvements were obtained in patients with neck pain (mean NDI change: 6.8/50) and lower back pain (50% obtaining more than the minimal clinically important change on the RMQ). This despite the high proportion of chronic complaints and multiple co-morbidities in the study population. The percentage of patients whose pain produced moderate to severe limitation of work outside the home dropped from 81% to 65%. Those significantly affected by emotional strain fell from 73% to 59%, and those able to work in the home rose from 60% to 84%.

Patient and provider satisfaction and sustainability

Table 5 Patients were asked to fill in a satisfaction questionnaire on completion of their treatment. (see Table 5) Results from the pooled satisfaction data indicated that patients were highly satisfied with both the outcome of care and with the various aspects of the process of care they received in the clinic. There was an endorsement of over 90% for "excellent" or "very good" across all parameters on the patient satisfaction survey.

Physicians were also surveyed about the inclusion of chiropractic services. All department family physicians were asked to complete the physician questionnaire that queried their satisfaction with the integration of the chiropractic services and the model. Seventeen of 40 available physicians completed the questionnaire (42.5 %). All respondents reported that they were highly satisfied with the inclusion of the chiropractic services and felt that these services should continue to be provided within the department. In both the interviews (qualitative project) and survey feedback, all health providers felt the inclusion of the services was important and should be maintained. They also stressed the importance of interprofessional education and collaborative practice as a means to improve the quality of care delivered to inner city patients. The chiropractic services have continued in the Department beyond research project completion. A shared funding mechanism between SMH and CMCC has enabled long-term provision of care and the establishment of a permanent program in the department. Services have now been available to patients for a period of over five years.

Discussion

Addressing the complex health issues of an inner city population is a challenge for health institutions that service these often marginalized communities. The delivery of team-based or integrative care is thought to improve patient outcomes and to enhance care delivery. [47] For this reason, the St. Michael‘s Hospital and the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College worked together with the Ministry of Health and Long Term Care and the Ontario Chiropractic Association in the development of a program, the first of its kind in Canada, to include a CAM therapy, chiropractic care, for the treatment of MSK pain conditions within an integrative model in the DFCM. The evaluation of this program utilized a mixed-methods approach to assess the overall programmatic success, the efficacy of the clinic‘s treatments and the satisfaction of patients and providers with the services. Observation, key informant interviews and questionnaires were used to evaluate the success of the program and model development. Validated clinical outcome instruments were used to determine whether clinical improvement occurred in the study population. Satisfaction surveys were used to evaluate patient and provider satisfaction.

A similar program involving the integration of "manual medicine" into a German hospital has been reported recently by Pioch et al. [48] This group reported on a two-year follow-up of 211 patients treated in the Clinic for Manual Medicine. Similar proportions of patients with low back, neck and peripheral joint pain as compared to the present study were included. Our clinical outcome results are comparable to those of Pioch et al whereby clinically important improvements in pain levels were achieved in the study population.

A recent report of hospital-based chiropractic treatment in Norway [49] is of some interest; however, this group restricted treatment to only 44 sciatica cases, whereas our study involved a much wider range of low back, neck and peripheral joint conditions. As a further difference, most of their patients received their treatments outside the hospital clinic as compared to our in-hospital ambulatory approach. Finally, none of the outcome measures reported in our study were used by the Norwegian team; only data on return to work were reported. It appears that the inclusion of chiropractic care did result in improved outcomes in this limited patient group evaluated by the Norwegians, similar to the study population described in our project.

Green et al [50] evaluated the referral patterns and attitudes of American primary care physicians towards chiropractors through use of a mailed survey. They found that while primary care physicians (PCP) generally had good relationships with other health providers, there was a lack of direct, formalized relationships between PCPs and chiropractors. They called for future research to evaluate the identification of facilitators and barriers to the development of relationships with chiropractors. In our study we were able to identify several barriers and facilitators to the development of the chiropractic program in a mainstream medical facility. The DFCM which housed the chiropractic program, was home to over 40 family physicians as well numerous other health providers (nurses, social workers, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, pharmacists and dieticians.) Several of these health providers, as well as department administrators, participated in the qualitative portion of this project and provided input into the identification of the barriers and facilitators that they perceived impacted the integration of the chiropractic program.

Figure 1 With respect to this clinical model of integration, the project team determined that the chiropractic services were successfully integrated in the department, according to Boon‘s criteria. [18] Funding, lack of space, lack of an electronic medical record and the geographical distribution of the four sites composing the DFCM spread out across the inner city posed barriers to the achievement of a fuller level of integration and easy accessibility of chiropractic services. The expertise of the chiropractors, the culture of the organization and the presence of a strong and credible advocate (champion) were all seen to be critical in enabling the success of this initiative. Figure 1 below depicts the location along Boon et al‘s practice model continuum, where the project team felt our program reached.

This was regularly less than 50%. There were several reasons for this; chief among them was the fact, noted above, that, for the majority of patients, the expected clear-cut discharge point for their initial complaint did not occur. Rather, secondary complaints were identified for which treatment was provided, and the "discharge" point for the initial complaint became blurred. As well, many patients were lost to follow-up due to lack of returning for discharge evaluation and/or failure to complete their treatment program. This is a problem that is faced by the DFCM as a whole in regard to providing continuity of care to this type of patient population.

Future work will focus on delineating an appropriate "post-intake" assessment period. An alternative approach would be to accept that many patients will remain "in-treatment" for an extended period of time (due to multiple, chronic or recurrent complaints) and that their progress can be monitored on a fixed set of intervals such as every six weeks. The disadvantage with this approach is that it may fail to identify the optimum point of clinical improvement. In this respect, at least the current data, obtained when discharge was evident, does reflect the optimum level of clinical change in our patients. Unfortunately, for some of the instruments, this is based on relatively few data points.

There appears to have been good acceptance of the application of outcomes measures among these patients. An overwhelming majority of them consented to participate in this aspect of the SMH-CC‘s initiative, and most of them did complete the intake package of outcomes measures. The high satisfaction ratings for the care processes in the Clinic should reflect, at least indirectly, that patients were satisfied with their participation in the outcomes assessment process. However, in the future, this should be tested more directly by adding some questions in the Satisfaction Scale on this matter.

With respect to the questionnaire completed by physicians, some bias in survey completion may have occurred as there is a chance that only those physicians who were satisfied with the inclusion of the services felt motivated enough to complete the instrument.

Conclusions

We have reported on an innovative program to integrate a CAM treatment service, chiropractic, into the primary care musculoskeletal services provided by a Canadian hospital to its inner city population. The success of this program has been confirmed through a mixed-methods evaluative process. Programmatic success was achieved by the concerted efforts of all stakeholders, especially when led by an institutional champion. High satisfaction with the program was reported by administrators, practitioners and patients. Clinical outcomes were evaluated by a standardized outcomes protocol. Our findings demonstrate that the majority of patients with MSK complaints obtained clinically important improvements when able to access chiropractic care. This is especially important given the frequency of chronic, complex complaints with numerous co-morbidities in our study population and the significant barriers these people face in accessing traditional hospital services. Our team found that CAM therapies may be useful adjuncts in the management of MSK pain conditions, even in highly systematized settings of primary care hospital clinics and for clinically complex and marginalized populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Wellesley Central and St. Michael‘s Hospital HIV/AIDS Community Advisory Panels, Mr. Tony Dipede, Mr. Jim O‘Neill, Dr. Philip Berger, Dr. Robert Howard, Ms. Anne-Marie Tynan, Mr. Chad Leaver and Ms. Nan Brooks, the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College and the Ontario Chiropractic Association for their support and assistance in this research project. The authors wish to thank the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care for funding this research.

References:

Bergenudd H, Nilsson B.

Back pain in middle age; occupational workload and psychologic factors: an epidemiologic survey.

Spine 1988:13(1):58-60.Hogg-Johnson, S, van der Velde, G, Carroll, LJ et al.

The Burden and Determinants of Neck Pain in the General Population:

Results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force

on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008 (Feb 15); 33 (4 Suppl): S39–51Martin BI. Deyo R. Mirza SK, et al.

Expenditures and Health Status Among Adults With Back and Neck Problems

JAMA 2008 (Feb 13); 299 (6): 656–664Glazier, R. Badley EM, Gilbert JE, Rothman L.

The nature of increased hospital use in poor neighbourhoods: findings from a Canadian Inner City.

Can J Public Health 2000;91(4):268-73.Wasylenki D.

Inner city health.

CMAJ 2001;164(2):214-5.City of Toronto [homepage on the internet].

Toronto. 2007 [cited 2009 July 15]. Toronto Neighborhood Profiles. Available from:

http://www.toronto.ca/ demographics/neighbourhoods.htmNew Zealand Ministry of Health [homepage on the internet].

Wellington 1998 [cited 2004 June 09].

Keating G. Integrated care – a view from the Ministry of Health. Available from:

http://www.know.govt.nz/integrated/ publication/gkic.htmlBoon H, Verhoef M, O‘Hara D, Findlay B, Majid N.

Integrative healthcare: arriving at a working definition.

Altern Ther Health Med 2004;10:48-56.Kelner M, Wellman B, Welsh S, Boon H.

How Far Can Complementary and Alternative Medicine Go?

The Case of Chiropractic and Homeopathy

Soc Sci Med. 2006 (Nov); 63 (10): 2617–2627Vohra S, Feldman K, Johnston B, Waters K, Boon H.

Integrating complementary and alternative medicine into academic health centres:

experience and perceptions of nine leading centres in North America.

BMC Health Serv Res 2005;5:78.Conboy L, Patel S, Kaptchuk TJ, Gottlieb B, Eisenberg D, Acevedo-Garcia D.

Sociodemographic determinants of the utilization of specific types of complementary and alternative medicine:

an analysis based on a nationally representative survey sample.

J Altern Complement Med 2005;11(6):977-94.Tindle HA, Davis RB, Phillips RS, Eisenberg DM.

Trends in use of complementary and alternative medicine by US adults: 1997-2002.

Altern Ther Health Med 2005;11(1):42-9.Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Van Rompay M, Kessler RC.

Trends in Alternative Medicine Use in the United States, 1990 to 1997:

Results of a Follow-up National Survey

JAMA 1998 (Nov 11); 280 (18): 1569–1575The Institute of Medicine. [homepage on the internet].

Washington. 2005. [cited 2009 May 16}.

Complementary and alternative medicine in the United States. Available from:

www.ion.edu/CMS/3793/4829/24431.aspxMacLennan AH, Wilson DH, Taylor AW.

Prevalence and cost of alternative medicines in Australia.

Lancet 1996;347:569-73.Rees L. Weil A.

Integrated medicine.

BMJ 2001;322(7279):119-20.Millar WJ.

Use of alternative health care practitioners by Canadians.

Can J Pub Health 1997;88(3):154-8.Boon H, Verhoef M, O‘Hara D, Findlay B.

From parallel practice to integrative health care: a conceptual framework.

BMC Health Serv Res 2004;4:15.Denzin NK, Lincoln YS.

Handbook of qualitative research 2nd ed.

In: Chambers I. Applied ethnography.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000:851-69.Berg BL.

Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. 2nd ed.

Needham Heights, MA: Allyn Bacon, 1995:133-77.Morgan DL:

Qualitative content analysis: A guide to paths not taken.

Qual Health Res1993:3(1):112-21.Boyzatzis R.

Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1998:1-28.Verhoef MJ, Mulkins A, Boon H.

Integrative health care: how can we determine whether patients benefit?

J Alt Comp Med 2005;11(Suppl 1):S57-S65.Verhoef MJ, Vanderheyden LC, Tryden T, Mallory D, Ware M.

Evaluating complementary and alternative medicine interventions:

in search of appropriate patient-centred outcome measures.

BMC Comp Alt Med 2006;6:38.Von Korff M, Jensen MP, Karoly P.

Assessing global pain severity by self-report in clinical and health services research.

Spine 2000;25:3140-51.Farrar JT, Young JP, Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole MR.

Clinical Importance of Changes in Chronic Pain Intensity

Measured on an 11-point Numerical Pain Rating Scale

Pain 2001 (Nov); 94 (2): 149-158Vernon HT, Mior S.

The Neck Disability Index: A Study of Reliability and Validity

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1991 (Sep); 14 (7): 409–415Pietrobon R, Coeytaux RR, Carey TS, Richardson WJ, DeVellis RF.

Standard scales for measurement of functional outcome for cervical pain or dysfunction: a systematic review.

Spine 2002;27(5):515-22.Riddle DL, Stratford PW.

Use of generic versus region-specific functional status measures on patients with cervical spine disorders.

Phys Ther 1998;78(9):951-63.Stratford PW, Binkley JM, Riddle DL.

Development and initial validation of the back pain functional scale.

Spine 2000;25(16):2095-2102.Roland M, Morris R.

A study of the natural history of low back pain: Part 1:

Development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low back pain.

Spine 1983;8:141-4.Lauridsen HH, Hartvigsen J, Manniche C, Korsholm L, Grunnet-Nilsson N.

Responsiveness and minimal clinically important difference for pain and disability instruments

in low back pain patients.

BMC Musculoskel Dis 2006;25,7:82.Rydeard R, Leger A, Smith D.

Pilates-based therapeutic exercise: effect on subjects with nonspecific chronic low back pain and

functional disability: a randomized controlled trial.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2006;36(7):472-84.Stratford PW, Binkley JM, Riddle DL, Guyatt GH.

Sensitivity to change of the Roland-Morris Back Pain Questionnaire: Part 1.

Phys Ther 1998;78:1186-96.Riddle DL, Stratford PW, Binkley JM.

Sensitivity to change of the Roland-Morris Back Pain Questionnaire: part 2.

Phys Ther 1998;78(11):1197-207.Stratford PW, Binkley J, Solomon P, Finch E, Gill C, Moreland J.

Defining the minimum level of detectable change for the Roland-Morris questionnaire.

Phys Therapy1996;76(4):359-65.Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD.

A 12-Item short-form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity.

Med Care 1996;34(3):220–33.Jenkinson C, Layte R, Jenkinson D, Lawrence K, Petersen S, Paice C, et al.

A shorter form health survey: Can the SF-12 replicate results from the SF-36 in longitudinal studies?

J Public Health Med 1997;19(2):179–86.Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, Apolone G, Bjorner JB, Brazier JE, et al.

Cross-validation of Item Selection and Scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in Nine Countries:

Results from the IQOLA Project.

J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51(11):1171–8.Lundberg L, Johannesson M, Isacson DGL, Borgquist L.

The relationship between health–state utilities and the SF-12 in a general population.

Med Decision Making 1999;19(2):128–40.Paterson C.

Measuring outcome in primary care: a patient-generated measure, MYMOP, compared to the SF-36 health survey.

BMJ 1996;312:1016-20.Paterson C, Britten N.

In pursuit of patient-centered outcomes: A qualitative evaluation of MYMOP, measure yourself medical outcome profile.

J Health Serv Res Policy 2000;5:27-36.Paterson C.

Complementary practitioners as part of the primary health care team:

consulting patterns, patient characteristics and patient outcomes.

Fam Prac 1997;14:347-54.Garner MJ, Aker P, Balon J, Birmingham M, Moher D, Keenan D, et al.

Chiropractic Care of Musculoskeletal Disorders in a Unique Population

Within Canadian Community Health Centers

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2007 (Mar); 30 (3): 165–170World Health Organization [home page on the internet].

Geneva; 2005 [cited 2008 June 4].

WHO guidelines for adverse event reporting and learning Systems. 2005.

Document # WHO/EIP/SPO/QPS/05.3. Available from:

http://www.who.int/patientsafety/events/05/Reporting_Guidelines.pdfOntario Workplace Safety and Insurance Board [home page on the internet].

Toronto; 2004 [cited 2009 June 2].

WSIB customer satisfaction 2004. Available from:

http://www.wsib.on.ca/wsib/wsibsite.nsf/LookupFiles/DownloadableFileCSSurvey04/$File/2004CstrSatisSurv.pdfRodriguez LSM, Beaulieu M-D, D‘Amour D, Ferrada-Videla M.

The determinants of successful collaboration: A review of theoretical and empirical studies.

J Interprof Care 2005;19(Suppl 1):132-47.Pioch E, Niemier K, Seidel W.

Manual medicine in the treatment of chronic musculoskeletal pain syndromes:

evaluation of an inpatient treatment program.

J Orthop Med 2006;28:4-12.Orlin J, Didricksen A.

Results of chiropractic treatment of lumbopelvic fixation in 44 patients admitted to an orthopaedic department.

J Manip Physiol Ther 2007;30:135-9.Greene BR, Smith M, Veerasathpurush A, Haas M.

Referral patterns and attitudes of Primary Care Physicians towards chiropractors.

BMC Comp Alt Med 2006;6:5.

Return to ALT-MED/CAM ABSTRACTS

Return to SPINAL PAIN MANAGEMENT

Since 9-29-2019

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |