Diagnostic Imaging of

the Temporomandibular Joint

By G. Patrick Thomas, Jr., DC, DACBR

A wide variety of conditions affect the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) including congenital anomalies, ankylosis, arthritis, and internal disk derangement. [1] TMJ disease is common, affecting between 4 and 28 percent of the population. Young females in particular commonly present with TMJ complaints. [2]

While standard imaging techniques, such as plain film radiography, are useful in characterizing many of these abnormalities, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is ideally suited to assess changes of the disk.

Brief Review of Anatomy and Function

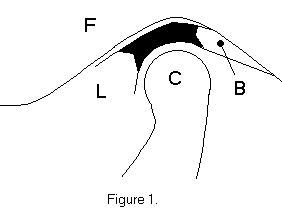

The TMJ consists not only of the condyle of the mandible and the articular fossa of the temporal bone, but also of a small interposed fibrous connective tissue meniscus or disk. This disk is attached posteriorly to the temporal bone by an elastic band know as the bilaminar zone. Anteriorly, the superior belly of the lateral pterygoid muscle fixes the disk into its normal position. [2]

The disk separates the joint into two compartments. The upper portion of the joint is capable of only translatory movements; anterior and posterior motion of the disk in relation to the temporal bone. The inferior joint space allows for rotation of the mandibular condyle (2).

The normal disk is held on top of the mandibular condyle by the opposing forces of the superior belly of the lateral pterygoid muscle and the bilaminar zone. Diseases and conditions that upset this balance can lead to joint dysfunction and anatomical derangement of the TMJ.

Figure one shows the articular fossa (F), the mandibular condyle (C), the lateral pterygoid muscle (L), and the bilaminar zone (B). The disk is black.

Two separate actions occur at the TMJ when the mouth is opened. The mandibular condyle rotates under the disk, and the disk translates anteriorly in relation to the articular fossa of the temporal bone. When the mouth closes this complex motion reverses, returning the disk to itís resting place under the articular fossa

Causes of Disk Derangement

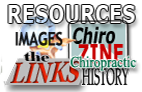

Chronic spasm of the lateral pterygoid muscle, trauma and arthritic changes, as well as defects of the bilaminar zone, can all lead to dysfunction and internal derangement of the TMJ (1). Two common patterns of derangement are recognized: Anterior disk displacement with reduction and anterior disk displacement without reduction. The first pattern is characterized by abnormal disk position with the mouth closed, and normal relationships of the disk, condyle and fossa with the mouth open. Anterior displacement without reduction indicates that the relationships of the three joint components are abnormal with the mouth both opened and closed. [2]

MRI Techniques in Evaluation of the TMJ

Spin-echo pulse sequences typically are used for MR imaging of the TMJ. The inherent contrast of the anatomy in the region makes T1-weighed images adequate in most cases. T2-weighted images are useful when joint fluid, tumor, edema or infections are suspected/ [2] Sagittal and coronal images are acquired with the patientís mouth opened and closed. Because of the small size of the structures of interest here, surface coils are essential for adequate signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio.

The important landmarks for assessment of TMJ function include the articular fossa of the temporal bone, the mandibular condyle, the disk, and the bilaminar zone.

The closed-mouth scans are examined first. Damage to the bilaminar zone allows the unopposed lateral pterygoid muscle to displace the disk anteriorly. This is seen as displacement of the disk anteriorly in relation to the articular fossa (see figure 2).

Next assessed is the relationship of the disk and the mandibular condyle with the patientís mouth opened. Normally the disk and the condyle move as a unit anteriorly when the mouth opens. If the disk is displaced with the mouth closed, and resumes itís normal relationship with the condyle when the mouth is opened, then anterior displacement with reduction is present (see figure 3). On the other hand, if when the mouth is opened, the condyle and the disk do not resume their normal relationship, anterior displacement without reduction is present (see figure 4). [2]

Treatment

Unfortunately, non-surgical treatment is effective in only 25% of patients with anterior displacement with reduction. Various intra-oral appliances and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications are common treatments.

Patients who suffer from anterior displacement without reduction are often treated surgically. If the disk is not fragmented or macerated it can be repositioned. Badly damaged disks are often removed and replaced with implants or grafts. [1]

Conclusion

Temporomandibular joint disease is a significant health problem, both in terms of itís impact to an individual and its incidence. Conventional imaging methods are often unable to properly detect and diagnose lesions of this articulation. MRI is ideally suited to assess both anatomical and functional disturbances

References:This article first appeared in the February 2002 issue of Missouri Chiropractor.

Berklow R (ed):

The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy

Rahway NJ, Merck and Co., 1992Edelman R and Hesselink J:

Clinical Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1990

Return to RADIOLOGY

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |