Bad is More Powerful Than Good:

The Nocebo Response in Medical ConsultationsThis section was compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: American Journal of Medicine 2015 (Feb); 128 (2): 126–9 ~ FULL TEXT

Maddy Greville-Harris, PhD, Paul Dieppe, MD

School of Psychology,

University of Southampton,

United Kingdom.

M.L.Greville-Harris@soton.ac.uk.

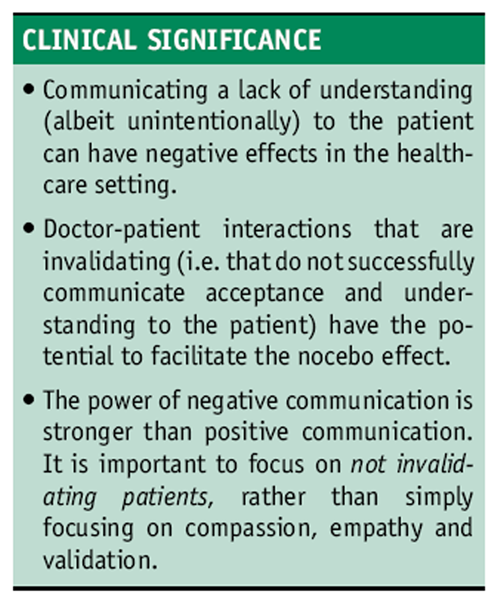

Although there has been a lot of research looking at the placebo response, nocebo responses in the healthcare setting have been largely overlooked. This article explores the potential role of negative patient-doctor communication in facilitating nocebo responses in the medical consultation. We suggest that invalidation, that is, communicating a lack of understanding and acceptance to the patient (albeit unintentionally), is a key factor in understanding the nocebo response. This article reviews evidence from the experimental and healthcare setting, which suggests that the negative effects of invalidation may be stronger than we think.

KEYWORDS: Communicating understanding; Doctor–patient interaction; Health communication; Invalidation; Nocebo response; Placebo response; Validation

Much attention has been given to the so-called placebo response, that is, people getting better in response to sham or dummy treatments that contain no active ingredient. [1] The opposite nocebo response, that is, people getting worse in response to sham interventions, has also been recognized for a long time, but has resulted in less attention from health researchers, [2, 3] who often focus on the ethical concerns around knowingly inducing such responses. [4–6]

Sham or dummy interventions, by definition, contain no active ingredients. Thus, the placebo/nocebo response must result from some other component of these interventions, such as the context in which they are administered or the dialogue that takes place between patients and healthcare professionals. Two psychological theories dominate our thinking about the ways in which placebo/nocebo responses are mediated: conditioning and expectation. For example, if we always take a red painkilling pill to relieve a headache, soon taking an inert red pill can relieve our pain, because we have unconsciously learned to associate a red pill with pain relief (conditioning), or we expect the pill to work (expectation). There are plenty of data to support the relevance of each of these factors in both the placebo and nocebo responses, [6–10] yet the examination of other mechanisms involved, particularly in nocebo research, has largely been overlooked. Although a lot of work focuses on the nocebo responses that result from information provision about possible drug side effects, [11–15] little research has focused on the role of negative communication between doctor and patient (ie, human interactions) more generally in facilitating nocebo responses in the healthcare setting.

Häuser et al [3] suggest that “doctor-patient communication and the patient’s treatment expectations can have considerable consequences, both positive and negative, on the outcome of a course of medical therapy,” and yet there has been little consideration of the nocebo responses brought about by doctor-patient interactions. We propose that the nocebo response can be facilitated by the patient responding negatively to the conversations they have with healthcare providers, who are advising them about interventions designed to improve their health. Specifically, we believe that, as well as the mechanisms just described, a key factor in understanding the nocebo response is the concept of validation and invalidation.

Validation and invalidation are constructs developed by Linehan [16] and others, [17–19] initially used as strategies in therapy [16] and more recently as communication strategies within the healthcare setting. [20] Although validation is the act of communicating acceptance and understanding to another person, invalidation is the opposite, communicating nonunderstanding and nonacceptance to another. These constructs differ from empathy and compassion in that they focus on communicating understanding and acceptance rather than merely understanding another (“empathy” [21]) or creating feelings of warmth, kindness, and support (“compassion” [22]).

Although there has been some recent interest in the validation/invalidation construct, [18–20] as with placebo and nocebo research, most research interest in validation has concentrated on positive outcomes (the value of validation) rather than negative effects (the damaging effects of invalidation). Yet, Baumeister et al [23] propose that the power of “bad” human interactions is stronger than “good” human interactions. We believe that the concept of “bad is more powerful than good” needs to be considered in the context of nocebo/placebo research and that we need to concentrate our attention more on how not to invalidate people, rather than empathy, compassion, and validation.

Our experimental findings from work with Anke Karl, Roelie Hempel, and Tom Lynch (unpublished material, 2013) support this idea; in a laboratory task, 90 participants carried out a series of math tasks designed to be stressful, while their physiologic responses were measured. Participants also rated their mood using a validated self-rated questionnaire (the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [24]) and subsequently recorded how safe they felt during the experiment and whether they would be willing to take part in the study again. During the tasks, participants were assigned randomly to receive validating, invalidating, or no feedback from the experimenter. The experimenter was trained to give consistently validating or invalidating feedback as rated on an established behavior coding scale (the Validation and Invalidation Behavior Coding Scale [Fruzzetti 2010; unpublished material]). For example, if the participant said that he/she found the task stressful, the experimenter might say “I don’t understand why you found it stressful — it’s just adding and subtracting numbers.” (invalidating response) or “that’s understandable — lots of people have said they found this task stressful.” (validating response).

There were significant differences between the invalidated participants and the other 2 groups on many of our measures, indicating a detrimental effect of invalidation in terms of psychological and psychological functioning. Invalidated participants showed significantly higher psychological arousal, significantly lower perceived safety ratings, higher ratings of negative mood, and less willingness to take part in the study again compared with the other 2 groups. Although we hypothesized that the placebo response might be due to validation, it was not the positive effects of validation but the negative effects of invalidation that were significant in this setting. [25]

Results in the clinical setting also supported this idea; consultations with patients at a pain management clinic were observed and recorded, and semistructured interviews were carried out with these patients (comprising 5 women with chronic widespread pain) and 4 consultants at the clinic. During the interviews, we played back excerpts from the patient’s consultation to discuss validating/invalidating behaviors in more detail. Interviews were then analyzed using thematic analysis, [25] whereby common themes were identified from the interview transcripts.

The interviews suggested that the effects of invalidation were very damaging. Both patients and consultants described many instances of feeling invalidated during chronic pain consultations. Patients reported feeling dismissed and disbelieved by healthcare providers, encountering providers who did not invest in them or show insight into their condition. Consultants described receiving conflict and criticism from patients, and encountering patients who held entrenched views or would not believe their diagnosis. Patients described feeling hopeless and angry after invalidating consultations, feeling an increased need to justify their condition or to avoid particular doctors or treatment altogether. Although the sample was small, these findings are in line with previous work. [26–33] Thus, invalidation during consultations may elicit powerful nocebo responses in patients that have so far not been adequately researched.

Although our research highlights the potential damage of invalidating interactions, Linton et al [34] propose that invalidating feedback can be delivered unintentionally. Literature on communication in healthcare puts emphasis on the need for professionals to be compassionate, to empathize with patients, and to reassure them without necessarily considering how they will respond to such actions. The validation/invalidation research highlights that professionals who believe that they are being compassionate and empathetic with the patient may be invalidating them, because the kindly, reassuring interaction may be interpreted as patronizing or indicative of a lack of belief in the severity of the condition by the patient. [34] For example, reassuring patients that there is nothing physically wrong with them, when they are in a great deal of pain, can leave them feeling misunderstood and delegitimized.

We also carried out an online study that highlighted the importance of how validating and invalidating feedback is perceived as well as delivered. A total of 425 participants took part in an online questionnaire about their emotions. Participants were randomly assigned to receive validating or invalidating feedback online about their skills in regulating their emotions. We found that feedback that was not in line with participants’ own views of themselves, regardless of whether such feedback was validating or invalidating, was less likely to be believed. [25] Moreover, validating feedback that was not in line with participants’ self-views was rated as less validating. Thus, it seems that we can easily invalidate, or fail to validate, if the intention of our words is misperceived by the receiver, particularly if we are communicating that we oppose the participant’s view of himself or herself in some way.

It is part of being human to want to feel understood by others, and our general life experience tells us that harsh words and criticism can hurt and have lasting negative effects. We believe that in the context of disease and illness where we need to be understood by health care professionals, the negative effects of an unsatisfactory human interaction can be particularly important. As Olshansky1 states, “a cold, uncaring, disinterested and emotionless physician will encourage a nocebo response. In contrast, a caring, empathetic, physician fosters trust, strengthens beneficent patient expectations, and elicits a strong placebo response.. The doctor, the nurse, the healthcare provider are the most valuable resources for healing patients.”

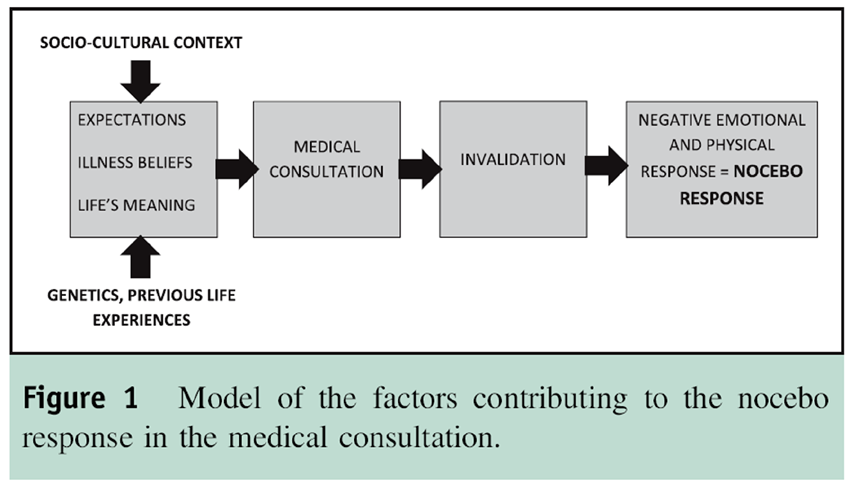

Our work indicates that the effects of invalidation may be stronger than we think, and the damaging effects extend to psychological changes in the body, as well as changes in our emotions and behaviors. This could lead to worsening of illness, and thus the “nocebo response.” Patients bring certain beliefs and expectations to their health care professional, which are molded by the culture they live in and their previous experiences. Their expectations will undoubtedly affect the outcome. In addition, some people may have been conditioned by previous negative experiences to respond negatively to a certain type of human interaction (Figure 1).We fully endorse the previous research and rhetoric that emphasize the importance of expectations and conditioning on nocebo responses. However, the negative power of an invalidating human to human interaction is potentially more important.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr Anke Karl, Dr Roelie Hempel, and Prof. Thomas Lynch for their input, help, expertise, and supervision of the PhD research described during this review; Prof. Alan Fruzzetti and his team for sharing their expertise on validation/invalidation techniques; Laura Scott for assistance in the experimental work; and the participants, patients, and clinicians who took part in these studies.

References:

Olshansky B.

Placebo and nocebo in cardiovascular health implications for healthcare, research, and the doctor-patient relationship.

J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:415-421.Colloca L, Sigaudo M, Benedetti F.

The role of learning in nocebo and placebo effects.

Pain. 2008;136:211-218.Häuser W, Hansen E, Enck P.

Nocebo phenomena in medicine: their relevance in everyday clinical practice.

Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109: 459-465.Benedetti F, Lanotte M, Lopiano L, Colloca L.

When words are painful: unraveling the mechanisms of the nocebo effect.

Neuroscience. 2007;147:260-271.Colloca L, Benedetti F.

Nocebo hyperalgesia: how anxiety is turned into pain.

Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2007;20:435-439.Enck P, Benedetti F, Schedlowski M.

New insights into the placebo and nocebo responses.

Neuron. 2008;59:195-206.Jensen KB, Kaptchuk TJ, Kirsch I, et al.

Nonconscious activation of placebo and nocebo pain responses.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:15959-15964.Pollo A, Carlino E, Vase L, Benedetti F.

Preventing motor training through nocebo suggestions.

Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112: 3893-3903.van Laarhoven AI, Vogelaar ML, Wilder-Smith OH, et al.

Induction of nocebo and placebo effects on itch and pain by verbal suggestions.

Pain. 2011;152:1486-1494.Benedetti F, Pollo A, Lopiano L, Lanotte M, Vighetti S, Rainero I.

Conscious expectation and unconscious conditioning in analgesic, motor, and hormonal placebo/nocebo responses.

J Neurosci. 2003;23: 4315-4323.Colloca L, Finniss D.

Nocebo effects, patient-clinician communication, and therapeutic outcomes.

JAMA. 2012;307:567-568.Colloca L, Miller FG.

The nocebo effect and its relevance for clinical practice.

Psychosom Med. 2011;73:598-603.Grimes DA, Schulz KF.

Nonspecific side effects of oral contraceptives: nocebo or noise?

Contraception. 2011;83:5-9.Wells RE, Kaptchuk TJ.

To tell the truth, the whole truth, may do patients harm: the problem of the nocebo effect for informed consent.

Am J Bioeth. 2012;12:22-29.Barsky AJ, Saintfort R, Rogers MP, Borus JF.

Nonspecific medication side effects and the nocebo phenomenon.

JAMA. 2002;287: 622-627.Linehan M.

Validation and psychotherapy.

In: Bohart A, Greenberg L, eds. Empathy Reconsidered: New Directions in Psychotherapy.

Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1997:353-392.Fruzzetti A, Worrall J.

Accurate expression and validating responses:

a transactional model for understanding individual and relationship distress.

In: Sullivan K, Davila J, eds.

Support Processes in Intimate Relationships.

New York: Oxford Press; 2010:121-152.Shenk CE, Fruzzetti AE.

The impact of validating and invalidating responses on emotional reactivity.

J Soc Clin Psychol. 2011;30:163-183.Linton SJ, Boersma K, Vangronsveld K, Fruzzetti A.

Painfully reassuring? The effects of validation on emotions and adherence in a pain test.

Eur J Pain. 2011;16:592-599.Vangronsveld KL, Linton SJ.

The effect of validating and invalidating communication on satisfaction, pain and affect in nurses suffering fromlow back pain during a semi-structured interview.

Eur J Pain. 2012;16:239-246.Rogers CR.

The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change.

J Consult Psychol. 1957;21:95-103.Gilbert P.

Introducing compassion-focused therapy.

Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2009;15:199-208.Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Finkenauer C, Vohs KD.

Bad is stronger than good.

Rev Gen Psychol. 2001;5:323-370.Tellegen A, Watson D, Clark LA.

Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales.

J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063-1070.Greville-Harris M.

Does Feeling Understood Matter? The Effects of Validating and Invalidating Interactions [doctoral thesis].

Exeter, UK: University of Exeter Medical School; 2013.Werner A, Malterud K.

It is hard work behaving as a credible patient: encounters between women with chronic pain and their doctors.

Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:1409-1419.Corbett M, Foster NE, Ong BN.

Living with low back pain- stories of hope and despair.

Soc Sci Med. 2007;65:1584-1594.Frantsve LM, Kerns RD.

Patienteprovider interactions in the management of chronic pain: current findings within the context of shared medical decision making.

Pain Med. 2007;8:25-35.Eccleston C, Williams DC, Amanda C, Rogers WS.

Patients’ and professionals’ understandings of the causes of chronic pain: blame, responsibility and identity protection.

Soc Sci Med. 1997;456: 699-709.Reid S, Whooley D, Crayford T, Hotopf M.

Medically unexplained symptomseGPs’ attitudes towards their cause and management.

Fam Pract. 2001;18:519-523.Fitzpatrick R.

Telling patients there is nothing wrong.

Br Med J. 1996;313:311-312.Wileman L, May C, Chew-Graham CA.

Medically unexplained symptoms and the problem of power in the primary care consultation: a qualitative study.

Fam Pract. 2002;19:178-182.Chew-Graham CA, May CR, Roland MO.

The harmful consequences of elevating the doctor-patient relationship to be a primary goal of the general practice consultation.

Fam Pract. 2004;21: 229-231.Linton SJ, McCracken LM, Vlaeyen JW.

Reassurance: help or hinder in the treatment of pain.

Pain. 2008;134:5-8.

Return to PLACEBOS

Since 2-27-2018

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |