Do Physical Therapists Follow Evidence-based Guidelines

When Managing Musculoskeletal Conditions?

Systematic ReviewThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: BMJ Open. 2019 (Oct 7); 9 (10): e032329 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Joshua Zadro, Mary O’Keeffe, Christopher Maher

Institute for Musculoskeletal Health,

Sydney School of Public Health,

Faculty of Medicine and Health,

The University of Sydney,

Camperdown, New South Wales, Australia.

OBJECTIVES: Physicians often refer patients with musculoskeletal conditions to physical therapy. However, it is unclear to what extent physical therapists' treatment choices align with the evidence. The aim of this systematic review was to determine what percentage of physical therapy treatment choices for musculoskeletal conditions agree with management recommendations in evidence-based guidelines and systematic reviews.

DESIGN: Systematic review.

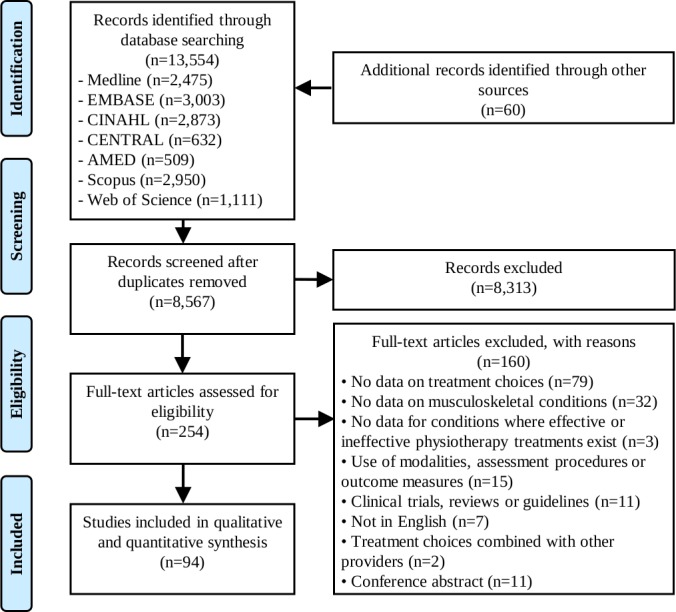

SETTING: We performed searches in Medline, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Allied and Complementary Medicine, Scopus and Web of Science combining terms synonymous with 'practice patterns' and 'physical therapy' from the earliest record to April 2018.

PARTICIPANTS: Studies that quantified physical therapy treatment choices for musculoskeletal conditions through surveys of physical therapists, audits of clinical notes and other methods (eg, audits of billing codes, clinical observation) were eligible for inclusion.

PRIMARY AND SECONDARY OUTCOMES: Using medians and IQRs, we summarised the percentage of physical therapists who chose treatments that were recommended, not recommended and had no recommendation, and summarised the percentage of physical therapy treatments provided for various musculoskeletal conditions within the categories of recommended, not recommended and no recommendation. Results were stratified by condition and how treatment choices were assessed (surveys of physical therapists vs audits of clinical notes).

RESULTS: We included 94 studies. For musculoskeletal conditions, the median percentage of physical therapists who chose recommended treatments was 54% (n=23 studies; surveys completed by physical therapists) and the median percentage of patients that received recommended physical therapy-delivered treatments was 63% (n=8 studies; audits of clinical notes). For treatments not recommended, these percentages were 43% (n=37; surveys) and 27% (n=20; audits). For treatments with no recommendation, these percentages were 81% (n=37; surveys) and 45% (n=31; audits).

CONCLUSIONS: Many physical therapists seem not to follow evidence-based guidelines when managing musculoskeletal conditions. There is considerable scope to increase use of recommended treatments and reduce use of treatments that are not recommended.

PROSPERO REGISTRATION NUMBER: CRD42018094979.

KEYWORDS: musculoskeletal; non-pharmacological; physical therapy; recommended care; systematic review; treatment choices

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Musculoskeletal conditions (such as back and neck pain) have remained the leading cause of disability worldwide over the past two decades and the burden is increasing. [1] Concerns about the harms of medicines such as opioids, and new evidence on the lack of effectiveness of common surgical procedures have shifted guideline recommendations for musculoskeletal conditions so there is now more explicit recommendation of non-pharmacological treatments such as those provided by physical therapists. For example, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention recommends exercise therapy instead of opioids in the management of chronic pain. [2] Similarly, the 2018 Royal Australian College of General Practitioners guideline for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis discourages opioids and arthroscopy for knee osteoarthritis and recommends aquatic and land-based exercise. [3]

Physicians often refer patients with musculoskeletal conditions to physical therapy for non-pharmacological care. In the USA, there are nearly 250,000 physical therapists [4] and in Australia there are now more practising physical therapists than general practitioners. [5, 6] It is important to appreciate however that there are a range of non-pharmacological treatments that physical therapists can provide; some such as exercise are recommended in guidelines for musculoskeletal conditions while others such as electrotherapy are recommended against. [7]

While there has been considerable attention in medicine on whether physicians are providing recommended care, there has been less attention on whether health services that physicians refer for involve recommended care. [8] Determining whether physical therapists are providing treatments recommended in evidence-based guidelines when they manage musculoskeletal conditions is an important step towards ensuring evidence-based care across all healthcare settings.

The aim of this systematic review was to summarise the percentage of physical therapy treatment choices for musculoskeletal conditions that agree with management recommendations in evidence-based guidelines and systematic reviews.

Methods

This review was conducted in accordance with the ‘Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses’ statement. [9] Due to the size of the review, other research questions in our registered protocol (including physical therapy treatment choices for cardiorespiratory and neurological conditions) will be addressed in separate manuscripts. Other deviations to our registered protocol include using a modified version of the ‘Downs and Black’ checklist to rate study quality and changing the focus from ‘high-value and low-value care’ to ‘recommended and not-recommended care’.

Data sources and searches

We conducted a comprehensive keyword search in Medline, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Allied and Complementary Medicine, Scopus and Web of Science, from the earliest record until April 2018. Our search strategy combined terms relating to ‘practice patterns’ and ‘physical therapy’ (Online Supplementary Table 1) PDF and was designed to capture studies investigating physical therapy treatment choices for any condition (as per our registered protocol). We performed citation tracking and reviewed the reference lists of included studies to identify those missed by our initial database search.

Two independent reviewers (JZ and MO) performed the selection of studies by subsequently screening the title, abstract and full text of studies retrieved through our electronic database search. Any disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved through discussion.

Study selection

We included any study that reported physical therapy treatment choices for musculoskeletal conditions through surveys of physical therapists (with or without vignettes), audits of clinical notes and other methods (eg, surveys of patients). We only included full-text studies in English. There was no restriction on the musculoskeletal condition treated (eg, neck pain, rehabilitation post knee arthroplasty) or practice setting (eg, private, public), but we excluded studies that reported treatment choices for conditions where there were no known effective or ineffective physical therapist-delivered treatments. We also excluded studies that only quantified physical therapists’ use of assessment procedures, outcome measures, referrals, treatments without specifying a target condition, pharmacological treatments (eg, recommending paracetamol) or treatments outside the usual scope of physical therapy practice (eg, injections); and studies where physical therapy treatment choices were unable to be separated from other healthcare providers.

Data extraction and quality assessment

One reviewer (JZ) independently extracted individual study characteristics (eg, condition, country, participant demographics) and percentages that quantified physical therapy treatment choices (see Data synthesis and Analysis sections). A second reviewer (MO) double checked the extracted data to ensure accuracy. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers and rechecking data against the original citation. We contacted authors when it appeared that relevant data were not reported.

The methodological quality of included studies was assessed independently by two reviewers (JZ and MO) using a modified version of the Downs and Black checklist. Any disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved through discussion. We modified the original 27-item Downs and Black checklist10 and selected eight items that were relevant to studies on treatment choices (Online Supplementary Table 2) PDF. For item eight, we considered the following assessments of treatment choices as ‘accurate’: observation, audits of clinical notes, audits of billing codes, treatment recording forms and validated surveys.

Data synthesis

The following definitions were used to classify treatments as recommended, not recommended and no recommendation:

Recommended treatments included physical therapy treatments endorsed in well-recognised evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (eg, guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, NICE) or found to be effective in recent systematic reviews. Treatments recommended in guidelines were further categorised as those that ‘must be provided’ (‘core’ treatments) and those that ‘should be considered’. When guidelines specified core treatments, only these treatments were considered ‘recommended’ in our primary analysis (see Treatment choices that involved treatments that were recommended, not recommended and had no recommendation section). Otherwise, treatments that should be considered were accepted as recommended.

Not-recommended treatments included physical therapy treatments not recommended in guidelines or found to be ineffective in recent systematic reviews.

Treatments with no recommendation included physical therapy treatments where guideline recommendations and evidence from systematic reviews was inconclusive, or where treatments had not been investigated in a systematic review.

We used one clinical practice guideline per condition to classify physical therapy treatments (primary guideline) and contacted leading experts to help us select our primary guideline and refine our classification for a number of conditions (see Acknowledgements). If we found a physical therapy treatment that was not mentioned in the primary guideline, we searched in other evidence-based clinical practice guidelines and systematic reviews to inform our classification (Online Supplementary Table 3) PDF. We selected recently published high-quality systematic reviews where possible.

Assessments of treatment choices

Data on physical therapy treatment choices were divided into two main categories (and analysed separately) due to differences in how each category is interpreted:

Treatment choices assessed by surveys completed by physical therapists (with or without vignettes)Interpretation. Surveys completed by physical therapists’ yielded data on the percentage of physical therapists that provide (survey without vignette) or would provide (survey with vignette) a particular treatment for a condition they frequently treat.

Survey without vignette. Physical therapists outlined the treatments they provide for a condition or rated how often they provide a particular treatment for a condition (eg, ‘frequently’; ‘sometimes’; ‘rarely’; or ‘never’). When studies reported how often treatments were provided, we extracted the percentage of treatments that were provided at least sometimes. We combined data when studies separated survey responses by different samples of physical therapists (usually by country or practice setting). Some surveys were completed by a senior physical therapist on behalf of the physical therapy department within a hospital (eg, management following knee arthroplasty).

Survey with vignette. Physical therapists outlined the treatments they would provide for a particular case (vignette). For studies that included multiple vignettes of the same condition, we took an average of physical therapists’ responses across vignettes of equal sample sizes or used data from the vignette with the highest sample size.

Treatment choices assessed by audits of clinical notes, audits of billing codes,

treatment recording forms, clinical observation or surveys completed by patientsInterpretation. These assessment measures (reported as ‘assessed by clinical notes’ in the results tables) yielded data on the percentage of patients that received a particular physical therapy-delivered treatment in a single treatment session or throughout an episode of care (ie, from initial consultation to discharge).

Audits of clinical notes and billing codes were performed retrospectively in the included studies. Treatment recording forms provided similar information to clinical notes, except they were often implemented as part of a study or registry on treatment practices (prospective). Within a study, we combined data across samples that presented with the same condition (eg, physical therapists from different countries treatment low back pain).

Analysis

We used counts and ranges to summarise study characteristics for each condition. We used medians and IQRs to summarise the percentage of physical therapy treatment choices that involved treatments that were recommended, not recommended and had no recommendation across studies. We provided an overall result for all studies and then separately for individual musculoskeletal conditions (eg, low back pain). Since physical therapists can provide multiple treatments for the same patient, and treatment choices were summarised across studies, the percentage of treatment choices that involved treatments that were recommended, not recommended and had no recommendation do not sum to 100%. For example, 70% of physiotherapists might provide recommended treatments for low back pain, but the same percentage might also provide some treatments that are not recommended or have no recommendation.

Treatment choices that involved treatments that were recommended,

not recommended and had no recommendation

Where possible, recommended treatment was based on treatment choices involving all core treatments recommended in guidelines (ie, physical therapists ‘must’ or ‘should’ provide). For example, the NICE guidelines for low back pain recommend that all patients receive advice and education to support self-management, reassurance and advice to keep active. [7] Since studies did not report combinations of treatments, we used the lowest value across all core treatments. For example, if 30% of physical therapists provide reassurance and 50% provide advice to stay active, we used 30% as the percentage of treatment choices that involved recommended treatments. This is because no more than 30% of the sample could have provided both reassurance and advice to stay active (core treatments).

If guidelines did not mention core treatments or if there were no guidelines for a condition, we used data from the most frequently provided recommended treatment that should be considered or was found to be effective in a systematic review. We used data from the most frequently provided treatment that was not recommended and had no recommendation to provide an estimate of the percentage of physical therapists’ treatment choices that involve at least one treatment that is not recommended and had no recommendation. For studies that reported treatment choices stratified by the duration of symptoms (acute vs chronic) or different settings (inpatient vs outpatient), we used the highest value of treatments that were recommended, not recommended and had no recommendation across the strata. We summarised the percentage of physical therapy treatment choices that were recommended, not recommended and had no recommendation across all musculoskeletal conditions where guidelines recommended core treatments.

Physical therapy treatments provided for various musculoskeletal conditions

We summarised the percentage of physical therapy treatments provided for various conditions within the categories of recommended, not recommended and no recommendation. Treatments that were procedurally similar and had the same recommendation (ie, recommended, not recommended and no recommendation) were grouped together. For example, according to the NICE low back pain guidelines, mobilisation, manipulation and massage should all be ‘considered’. [7] Hence, these were grouped as ‘manual therapy’. Studies rarely reported combinations of physical therapy treatments, so we used data from the most frequently provided treatment where appropriate. For example, if 67% of physical therapists provide massage for acute low back pain and 20% provide mobilisation, we used 67% as the best estimate for the percentage of physical therapists that provide manual therapy.

Patient or public involvement

Patients and members of the public were not involved in the design of this study.

Results

Figure 1

Table 1 After removing duplicates and screening 8,567 titles and abstracts and 254 full-texts reports, 94 studies were included (Figure 1). Physical therapy treatment choices were investigated for

low back pain (n=48 studies), [11–58]

knee pain (n=10), [32, 34, 57, 59–65]

neck pain or whiplash (n=11), [15, 18, 32, 34, 51, 66–71]

foot or ankle pain (n=5), [72–76]

shoulder pain (n=7), [15, 51, 77–81]

pre or post knee arthroplasty (n=6) [46, 82–86] (including one study of hip and knee arthroplasty [86]) and

other musculoskeletal or orthopaedic conditions (where treatment choices were only reported in one study or where one of either recommended or not recommended treatments could not be inferred from guidelines or systematic reviews) (n=18). [87–104]We contacted 15 authors for data (regarding 18 studies): 12 responded and 5 were able to provide the data we requested (regarding six studies). [15, 16, 22, 64, 89, 100] A summary of study characteristics across conditions is presented in Table 1. Characteristics of included studies are presented in Online Supplementary Table 4 PDF.

Seven studies investigated treatment choices for shoulder pain:four [15 78 80 81] focused on subacromial pain syndrome (the most common form of shoulder pain [105]),

two [77 79] included patients with various diagnoses (including subacromial pain syndrome) and

one [51] did not specify a diagnosis (online supplementary table 4).Evidence on the management of subacromial pain syndrome was used to categorise treatment choices for all studies on shoulder pain. Similarly, evidence on the management of lateral ankle sprains was used to categorise treatment choices for all studies on acute ankle injuries (n=2/3 studies on lateral ankle sprains [75 76]) and evidence on the management of knee osteoarthritis for all studies on knee pain (excluding one study on acute knee injuries [57] and another on a mixed sample of hip and knee osteoarthritis60 — Online Supplementary Table 5.).

Methodological quality

Individual study scores ranged from 4 to 8 (out of a possible 8) with a mean score of 6.0 (median=6) (Online Supplementary Table 6). The most common methodological limitations included failing to report that physical therapists who were prepared to participate were representative of the population from which they were drawn (n=88/94) and not using an accurate assessment of treatment choices (n=55/94). All studies clearly described their main findings and used appropriate statistical tests, and most scored positive on the remaining checklist items (online supplementary table 6).

Treatment choices that involved treatments that were recommended,

not recommended and had no recommendation (all studies)

Table 2

Figure 2

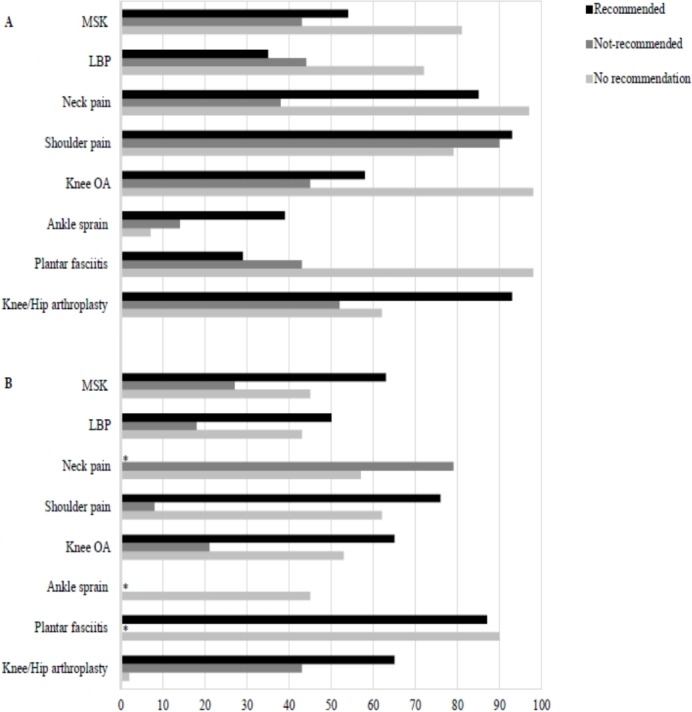

Treatment choices assessed by surveys completed by physical therapists (with or without vignettes) The median percentage of physical therapists that provide (or would provide) treatments that were recommended, not recommended and had no recommendation was 54%, 43% and 81% for all musculoskeletal conditions, respectively; 35%, 44% and 72% for low back pain; 85%, 38% and 97% for neck pain and whiplash; 93%, 90% and 79% for shoulder pain; 58%, 45% and 98% for knee pain; 39%, 14% and 7% for lateral ankle sprains; 29%,43% and 98% for plantar fasciitis; and 93%, 52% and 62% following knee or hip arthroplasty (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Treatment choices assessed by audits of clinical notes, audits of billing codes, treatment recording forms, clinical observation or surveys completed by patients The median percentage of patients that received physical therapy-delivered treatments that were recommended, not recommended and had no recommendation was 63%, 27% and 45% for all musculoskeletal conditions, respectively; 50%, 18% and 43% for low back pain; 79% (not recommended) and 57% (no recommendation) for neck pain and whiplash; 76%, 8% and 62% for shoulder pain; 65%, 21% and 53% for knee pain; 45% (no recommendation) for lateral ankle sprains; 87% (recommended) and 90% (no recommendation) for plantar fasciitis; and 65%, 43% and 2% following knee or hip arthroplasty (table 2 and figure 2).

Physical therapy treatment choices for various musculoskeletal conditions

Table 3 The results summarising the percentage of physical therapy treatments provided for various musculoskeletal conditions that were recommended, not recommended and had no recommendation can be found in Table 3. For example, as assessed by surveys of physical therapists, the most frequently provided recommended treatment for acute low back pain that physical therapists ‘must provide’ was advice to stay active (median=32%, IQR 13%–55%, n=7 studies). The most frequently provided not recommended treatment for acute low back pain was McKenzie therapy (median=36%, IQR 24%–37%, n=6) (table 3). Treatment choices for conditions that were only reported in one study or where one of either recommended or not recommended treatments could not be inferred from guidelines or systematic reviews can be found in online supplementary table 5.

Discussion

Many physical therapists seem not to follow evidence-based guidelines when managing musculoskeletal conditions. Our review highlights that there is considerable scope to increase the frequency with which physical therapists provide recommended treatments for musculoskeletal conditions and reduce the use of treatments that are not recommended or have no recommendation to guide their use. Across all musculoskeletal conditions, 54% of physical therapists chose recommended treatments, 43% chose treatments that were not recommended and 81% chose treatments that have no recommendation (based on surveys completed by physical therapists). Based on audits of clinical notes, 63% of patients received recommended physical therapy-delivered treatments, 27% received treatments that were not recommended and 45% received treatments that have no recommendation.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The primary strength of this review is that we used a systematic approach to identify studies on physical therapy treatment choices and classified recommendations for physical therapy treatments according to evidence-based guidelines and systematic reviews (online supplementary table 3). Experts provided feedback to help refine our classification, and a second reviewer double checked all the extracted data to ensure accuracy.

The main weakness of this review is that primary studies only reported treatment choices for individual treatments and not combinations of treatments. As a result, we could not determine the percentage of physical therapists that provided only recommended treatments, only not-recommended treatments, only treatments with no recommendation or other combinations of treatments. Second, it is possible that recommended treatments such as advice and reassurance were not documented in clinical notes or listed in a survey because they are viewed as a routine part of physical therapy. For example, only 12 out of the 48 studies on low back pain reported that physical therapists provide advice to stay active, while even less reported reassurance (n=2) or advice and education to support self-management (n=2). This could have underestimated the percentage of recommended treatment choices. Third, physical therapists’ treatment choices may have changed over time so including older studies could limit the relevance of our findings.

Nevertheless, we do not believe that this is an important limitation because many guideline recommendations have remained largely consistent overtime. For example, although some studies on treatment choices for low back pain are from 1994, a comparison of low back pain guidelines between 1994 and 2000 found a high degree of consistency of recommendations, such as advice to stay active and avoid bed rest. [106] This is consistent with current low back pain guidelines. Finally, most studies did not use an accurate assessment of treatment choices (n=55/94). However, we stratified our analysis by how treatment choices were assessed so the influence of having an accurate method of assessment is clear to readers.

Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other studies

Our finding that approximately half of treatment choices involved recommended treatments is similar to previous studies of healthcare. For example, the CareTrack study in Australia found that 57% of healthcare provided by general practitioners, specialists, physiotherapists, chiropractors, psychologists and counsellors was appropriate, [107] while the earlier CareTrack study in the USA found a figure of 55%.108 The percentage of recommended treatment choices for low back pain however was lower in our review (35%–50%) when compared with estimates from the Australian (72%) [107] and USA (69%) CareTrack studies. [108] A difference to our study is that the CareTrack studies used consensus of experts to judge the value of care, whereas we based this decision on evidence-based practice guidelines and systematic reviews. Another difference is that the CareTrack studies only assessed healthcare decisions through audits of clinical notes; we used audit of clinical notes, surveys, vignettes and clinical observation. Further, the Care Track studies reported primary data collected and were not systematic reviews.

Meaning of the study

Our results suggest that physical therapy treatment choices for musculoskeletal conditions are often not based on research evidence. There was extensive use of not-recommended treatments and treatments without recommendations; for some conditions, treatments that were not recommended or had no recommendation were more common choices than recommended treatments (figure 2). As there are now over 42,000 clinical practice guidelines, systematic reviews and clinical trials to guide physical therapy practice, the challenge in physical therapy is applying this evidence to practice. Professional associations have a potential role to play in this area. Unfortunately, recent marketing from professional associations, popular social media handles and leading journals have emphasised the importance of early referral to physical therapy [109] rather than the nature of physical therapy care provided. The high percentage of non-evidence-based treatment choices in our review suggests that referring patients with musculoskeletal conditions for early physical therapy—without emphasising the importance of the type of non-pharmacological care they receive—may be unwise.

Treatment waste is another important issue highlighted in our review. Even when patients receive recommended treatments, they also usually receive not-recommended treatments and treatments that have no recommendation to guide their use. With nearly US$ 100 billion spent on physical therapy, optometry, podiatry or chiropractic medicine each year in the USA, [110] the waste due to non-evidence-based physical therapy is likely enormous. Further, billing patients for physical therapy treatments that are not evidence based could also be considered unethical; the Vision Statement of the American Physical Therapy Association makes clear that there is an expectation that ‘physical therapists and physical therapist assistants will render evidence-based services’. [111]

Unanswered questions and future research

Understanding what drives poor patterns of physical therapy care is important as it will guide the design of strategies to ensure the use of treatments that are not recommended for musculoskeletal conditions does not simply shift from medicine to allied health. One possible explanation is the large variation in physical therapists who receive training in evidence-based practice (21%–82%) and can critically appraise research papers (48%–70%) (systematic review of 12 studies [112]). Physical therapists with a poor understanding of evidence-based practice might be misled into providing treatments with weak supporting evidence. Another explanation is a lack of awareness of, and agreement with, evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. For example, only 12% of physical therapists are aware of clinical practice guidelines for low back pain (survey of 108 physical therapists) [113] and 46% agree that guidelines should inform the management of low back pain (survey of 274 physical therapists). [39]

A recent initiative that could help physical therapists replace treatments that are not recommended with recommended treatments is Choosing Wisely. [114] Over 225 professional societies worldwide endorse Choosing Wisely and have published lists of tests and treatments that clinicians and their patients should question. This includes physical therapy associations in Australia, the USA and Italy. Testing strategies to increase adoption of Choosing Wisely recommendations among physical therapists is important. However, existing Choosing Wisely recommendations are likely not maximising the potential of the campaign to reduce the use of physical therapy treatments that are not recommended in guidelines and systematic reviews. For example, half of the Australian Physiotherapy Association Choosing Wisely recommendations target diagnostic testing that is not recommended, while other recommendations target treatments not part of routine physical therapy care, such as whirlpools for wound management and bed rest following diagnosis of acute deep vein thrombosis (American Physical Therapy Association). Our review highlighted the most frequently provided not-recommended non-pharmacological physical therapy treatments across a range of musculoskeletal conditions (table 3) and could be used to enhance the relevance of future Choosing Wisely recommendations. Further, in countries where physical therapists bill for specific treatments (eg, the USA), another approach could be to restrict funding for anything but recommended physical therapy treatments.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that that there is considerable scope to increase the contribution physical therapists could make to managing musculoskeletal conditions by increasing the frequency with which they provide treatments that are recommended in guidelines and systematic reviews and reduce their use of treatments that are not recommended or have no recommendations to guide their use.

Appendix A.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to thank Annette Bishop, David Spitaels, Susanne Bernhardsson, David Evans and Melissa Peterson who provided additional data for this study. They would also like to thank Mark Elkins, Rana Hinman, Rachelle Buchbinder, Clair Hiller and Louise Ada for helping them categorise physical therapy treatments as recommended, not recommended and with no recommendation, and Robert Herbert for providing comments on the manuscript.

Funding:

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests:

All authors declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

References:

Disease GBD;

Global, Regional, and National Incidence, Prevalence, and Years Lived With

Disability for 328 Diseases and Injuries for 195 Countries, 1990-2016:

A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016

Lancet. 2017 (Sep 16); 390 (10100): 1211–1259Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R.

CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain: United States, 2016

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

Recommendations and Reports Vol. 65 No. 1 March 18, 2016The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners

Guideline for the management of knee and hip osteoarthritis. 2nd edn

East Melbourne: Vic: RACGP, 2018.American Physical Therapy Association (APTA)

Accredited Pt and PTA programs Drectory. Available:

http://aptaapps.apta.org/accreditedschoolsdirectory/default.aspx?UniqueKey&UniqueKey=

[Accessed 18th Mar 2019].Physiotherapy Board of Australia

Registrant data Reporting period: 1 October 2017 – 31 December 2017. Available:

http://www.physiotherapyboard.gov.au/About/Statistics.aspx

[Accessed 18th Mar 2019].Medical Board of Australia Registrant data

Reporting period: 1 October 2017 – 31 December 2017. Available:

http://www.medicalboard.gov.au/News/Statistics.aspx

[Accessed 18th Mar 2019].National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE):

Low Back Pain and Sciatica in Over 16s: Assessment and Management (PDF)

NICE Guideline, No. 59 2016 (Nov): 1–1067Brownlee S, Chalkidou K, Doust J, et al. .

Evidence for overuse of medical services around the world.

The Lancet 2017;390:156–68. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32585-5Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009)

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses:

The PRISMA Statement

Int J Surg 2010; 8 (5): 336–341Downs SH, Black N.

The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both

of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions.

J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52:377–84. 10.1136/jech.52.6.377Armstrong MP, McDonough S, Baxter GD.

Clinical guidelines versus clinical practice in the management of low back pain.

Int J Clin Pract 2003;57:9–13Ayanniyi O, Lasisi OT, Adegoke BOA, et al. .

Management of low back pain: attitude and treatment preferences of physiotherapist in Nigeria.

Afr J Biomed Res 2007;10:41–9.Battié MC, Cherkin DC, Dunn R, et al. .

Managing low back pain: attitudes and treatment preferences of physical therapists.

Phys Ther 1994;74:219–26. 10.1093/ptj/74.3.219Bekkering GE, Hendriks HJM, van Tulder MW, et al. .

Effect on the process of care of an active strategy to implement clinical guidelines

on physiotherapy for low back pain: a cluster randomised controlled trial.

Qual Saf Health Care 2005;14:107–12. 10.1136/qshc.2003.009357Bernhardsson S, Öberg B, Johansson K, et al. .

Clinical practice in line with evidence? A survey among primary care physiotherapists

in Western Sweden.

J Eval Clin Pract 2015;21:1169–77. 10.1111/jep.12380Bishop A, Foster NE, Thomas E, et al. .

How does the self-reported clinical management of patients with low back pain relate to

the attitudes and beliefs of health care practitioners? A survey of UK general

practitioners and physiotherapists.

Pain 2008;135:187–95. 10.1016/j.pain.2007.11.010Byrne K, Doody C, Hurley DA.

Exercise therapy for low back pain: a small-scale exploratory survey of current

physiotherapy practice in the Republic of Ireland acute hospital setting.

Man Ther 2006;11:272–8. 10.1016/j.math.2005.06.002Carlesso LC, Macdermid JC, Santaguida PL, et al. .

Beliefs and practice patterns in spinal manipulation and spinal motion palpation reported by

Canadian manipulative physiotherapists.

Physiotherapy Canada 2013;65:167–75. 10.3138/ptc.2012-11Casserley-Feeney SN, Bury G, Daly L, et al. .

Physiotherapy for low back pain: differences between public and private healthcare

sectors in Ireland— A retrospective survey.

Man Ther 2008;13:441–9. 10.1016/j.math.2007.05.017de Souza FS, Ladeira CE, Costa LOP.

Adherence to back pain clinical practice guidelines by Brazilian physical therapists:

a cross-sectional study.

Spine 2017;42:E1251–E1258. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002190Ehrmann-Feldman D, Rossignol M, Abenhaim L, et al. .

Physician referral to physical therapy in a cohort of workers compensated for low back pain.

Phys Ther 1996;76:150–6. 10.1093/ptj/76.2.150Evans DW, Breen AC, Pincus T, et al. .

The effectiveness of a posted information package on the beliefs and behavior of musculoskeletal

practitioners: the UK chiropractors, osteopaths, and musculoskeletal physiotherapists low back

pain management (complement) randomized trial.

Spine 2010;35:858–66. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181d4e04bFidvi N, May S.

Physiotherapy management of low back pain in India - a survey of self-reported practice.

Physiother Res Int 2010;15:150–9. 10.1002/pri.458Foster NE, Thompson KA, Baxter GD, et al. .

Management of nonspecific low back pain by physiotherapists in Britain and Ireland.

A descriptive questionnaire of current clinical practice.

Spine 1999;24:1332–42. 10.1097/00007632-199907010-00011Freburger JK, Carey TS, Holmes GM.

Physical therapy for chronic low back pain in North Carolina: overuse, underuse, or misuse?

Phys Ther 2011;91:484–95. 10.2522/ptj.20100281Gracey JH, McDonough SM, Baxter GD.

Physiotherapy management of low back pain: a survey of current practice in Northern Ireland.

Spine 2002;27:406–11. 10.1097/00007632-200202150-00017Groenendijk JJ, Swinkels ICS, de Bakker D, et al. .

Physical therapy management of low back pain has changed.

Health Policy 2007;80:492–9. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.05.008Hamm L, Mikkelsen B, Kuhr J, et al. .

Danish physiotherapists' management of low back pain.

Adv Physiother 2003;5:109–13. 10.1080/14038190310004871Harte AA, Gracey JH, Baxter GD.

Current use of lumbar traction in the management of low back pain:

results of a survey of physiotherapists in the United Kingdom.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005;86:1164–9. 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.11.040Hendrick P, Mani R, Bishop A, et al. .

Therapist knowledge, adherence and use of low back pain guidelines to inform clinical decisions –

a national survey of manipulative and sports physiotherapists in New Zealand.

Man Ther 2013;18:136–42. 10.1016/j.math.2012.09.002Jackson DA.

How is low back pain managed?

Physiotherapy 2001;87:573–81. 10.1016/S0031-9406(05)61124-8Jette AM, Delitto A.

Physical therapy treatment choices for musculoskeletal impairments.

Phys Ther 1997;77:145–54. 10.1093/ptj/77.2.145Jette AM, Smith K, Haley SM, et al. .

Physical therapy episodes of care for patients with low back pain.

Phys Ther 1994;74:101–10. 10.1093/ptj/74.2.101Jette DU, Jette AM.

Professional uncertainty and treatment choices by physical therapists.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997;78:1346–51. 10.1016/S0003-9993(97)90308-7Keating JL, McKenzie JE, O'Connor DA, et al. .

Providing services for acute low-back pain: a survey of Australian physiotherapists.

Man Ther 2016;22:145–52. 10.1016/j.math.2015.11.005Kerssens JJ, Sluijs EM, Verhaak PF, et al. .

Back care instructions in physical therapy: a trend analysis of individualized

back care programs.

Phys Ther 1999;79:286–95.Ladeira CE, Cheng MS, da Silva RA.

Clinical specialization and adherence to evidence-based practice guidelines for

low back pain

management: a survey of US physical therapists.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2017;47:347–58. 10.2519/jospt.2017.6561Ladeira CE, Samuel Cheng M, Hill CJ.

Physical therapists' treatment choices for non-specific low back pain in Florida:

an electronic survey.

J Man Manip Ther 2015;23:109–18. 10.1179/2042618613Y.0000000065Li LC, Bombardier C.

Physical therapy management of low back pain: an exploratory survey of therapist approaches.

Phys Ther 2001;81:1018–28.Liddle SD, David Baxter G, Gracey JH.

Physiotherapists' use of advice and exercise for the management of chronic low back pain:

a national survey.

Man Ther 2009;14:189–96. 10.1016/j.math.2008.01.012Louw QA, Morris LD.

Physiotherapeutic acute low back pain interventions in the private health sector of the

Cape Metropole, South Africa.

S Afr J Physiother 2010;66:8–14. 10.4102/sajp.v66i3.68Madson TJ, Hollman JH.

Lumbar traction for managing low back pain: a survey of physical therapists in the United States.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2015;45:586–95. 10.2519/jospt.2015.6036Mielenz TJ, Carey TS, Dyrek DA, et al. .

Physical therapy utilization by patients with acute low back pain.

Phys Ther 1997;77:1040–51. 10.1093/ptj/77.10.1040Mikhail C, Korner-Bitensky N, Rossignol M, et al. .

Physical therapists' use of interventions with high evidence of effectiveness in

the management of a hypothetical typical patient with acute low back pain.

Phys Ther 2005;85:1151–67.Oppong-Yeboah B, May S.

Management of low back pain in Ghana: a survey of self-reported practice.

Physiother Res Int 2014;19:222–30. 10.1002/pri.1586Turner PA, Harby-Owren H, Shackleford F, et al. .

Audits of physiotherapy practice.

Physiother Theory Pract 1999;15:261–74. 10.1080/095939899307667Pensri P, Foster NE, Srisuk S, et al. .

Physiotherapy management of low back pain in Thailand: a study of practice.

Physiother Res Int 2005;10:201–12. 10.1002/pri.16Pincus T, Greenwood L, McHarg E.

Advising people with back pain to take time off work: a survey examining the role of

private musculoskeletal practitioners in the UK.

Pain 2011;152:2813–8. 10.1016/j.pain.2011.09.010Poitras S, Blais R, Swaine B, et al. .

Management of work-related low back pain: a population-based survey of physical therapists.

Phys Ther 2005;85:1168–81.Reid D, Larmer P, Robb G, et al. .

Use of a vignette to investigate the physiotherapy treatment of an acute episode of low back pain:

report of a survey of New Zealand physiotherapists.

New Zealand J Physiother 2002;30:26–32.Serrano-Aguilar P, Kovacs FM, Cabrera-Hernández JM, et al. .

Avoidable costs of physical treatments for chronic back, neck and shoulder pain within the

Spanish National health service: a cross-sectional study.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011;12:287 10.1186/1471-2474-12-287Sparkes V.

Treatment of low back pain: monitoring clinical practice through audit.

Physiotherapy 2005;91:171–7. 10.1016/j.physio.2004.10.007 10.1016/j.physio.2004.10.007Stevenson K, Lewis M, Hay E.

Does physiotherapy management of low back pain change as a result of an evidence-based

educational programme?

J Eval Clin Pract 2006;12:365–75. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00565.xStrand LI, Kvale A, Råheim M, et al. .

Do Norwegian manual therapists provide management for patients with acute low back pain

in accordance with clinical guidelines?

Man Ther 2005;10:38–43. 10.1016/j.math.2004.07.003Swinkels ICS, van den Ende CHM, van den Bosch W, et al. .

Physiotherapy management of low back pain: does practice match the Dutch guidelines?

Aust J Physiother 2005;51:35–41. 10.1016/S0004-9514(05)70051-9Tumilty S, Adhia DB, Rhodes R, et al. .

Physiotherapists’ treatment techniques in New Zealand for management of acute nonspecific

low back pain and its relationships with treatment outcomes: a pilot study.

Phys Ther Rev 2017;22:95–100. 10.1080/10833196.2017.1282073van Baar ME, Dekker J, Bosveld W.

A survey of physical therapy goals and interventions for patients with back and knee pain.

Phys Ther 1998;78:33–42. 10.1093/ptj/78.1.33van der Valk RWA, Dekker J, van Baar ME.

Physical therapy for patients with back pain.

Physiotherapy 1995;81:345–51. 10.1016/S0031-9406(05)66795-8Ayanniyi O, Egwu RF, Adeniyi AF.

Physiotherapy management of knee osteoarthritis in Nigeria—A survey of self-reported

treatment preferences.

Hong Kong Physiother J 2017;36:1–9. 10.1016/j.hkpj.2016.07.002Barten D-JJA, Swinkels llseCS, Dorsman SA, et al. .

Treatment of hip/knee osteoarthritis in Dutch general practice and physical therapy practice:

an observational study.

BMC Fam Pract 2015;16:75 10.1186/s12875-015-0295-9Holden MA, Nicholls EE, Hay EM, et al. .

Physical therapists' use of therapeutic exercise for patients with clinical knee osteoarthritis

in the United Kingdom: in line with current recommendations?

Phys Ther 2008;88:1109–21. 10.2522/ptj.20080077Jamtvedt G, Dahm KT, Holm I, et al. .

Measuring physiotherapy performance in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee:

a prospective study.

BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:145 10.1186/1472-6963-8-145MacIntyre NJ, Busse JW, Bhandari M.

Physical therapists in primary care are Interested in high quality evidence regarding

efficacy of therapeutic ultrasound for knee osteoarthritis: a provincial survey.

Sci World J 2013;7.Spitaels D, Hermens R, Van Assche D, et al. .

Are physiotherapists adhering to quality indicators for the management of knee osteoarthritis?

an observational study.

Musculoskelet Sci Pract 2017;27:112–23. 10.1016/j.math.2016.10.010Walsh NE, Hurley MV.

Evidence based guidelines and current practice for physiotherapy management of

knee osteoarthritis.

Musculoskeletal Care 2009;7:45–56. 10.1002/msc.144Ayanniyi O, Mbada CE, Oke AM.

Pattern and management of neck pain from cervical spondylosis in physiotherapy clinics

in South West Nigeria.

J Clin Sci 2007;7:1–5.Carlesso LC, Gross AR, MacDermid JC, et al. .

Pharmacological, psychological, and patient education interventions for patients with

neck pain: results of an international survey.

J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2015;28:561–73. 10.3233/BMR-140556Lisa C Carlesso, Joy C MacDermid, Anita R Gross, David M Walton, et al.

Treatment Preferences Amongst Physical Therapists and

Chiropractors for the Management of Neck Pain:

Results of an International Survey

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2014 (Mar 24); 22 (1): 11Corkery MB, Edgar KL, Smith CE.

A survey of physical therapists' clinical practice patterns and adherence to

clinical guidelines in the management of patients with whiplash associated disorders (WAD).

J Man Manip Ther 2014;22:75–89. 10.1179/2042618613Y.0000000048Ng TS, Pedler A, Vicenzino B, et al. .

Physiotherapists' beliefs about Whiplash-associated disorder: a comparison between Singapore

and Queensland, Australia.

Physiother Res Int 2015;20:77–86. 10.1002/pri.1598 +Rebbeck T, Maher CG, Refshauge KM.

Evaluating two implementation strategies for whiplash guidelines in physiotherapy:

a cluster randomised trial.

Aust J Physiother 2006;52:165–74. 10.1016/S0004-9514(06)70025-3Fraser JJ, Glaviano NR, Hertel J.

Utilization of physical therapy intervention among patients with plantar fasciitis

in the United States.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2017;47:49–55. 10.2519/jospt.2017.6999Grieve R, Palmer S.

Physiotherapy for plantar fasciitis: a UK-wide survey of current practice.

Physiotherapy 2017;103:193–200. 10.1016/j.physio.2016.02.002Kooijman MK, Swinkels ICS, Veenhof C, et al. .

Physiotherapists’ compliance with ankle injury guidelines is different for patients with

acute injuries and patients with functional instability: an observational study.

J Physiother 2011;57:41–6. 10.1016/S1836-9553(11)70006-6Leemrijse CJ, Plas GM, Hofhuis H, et al. .

Compliance with the guidelines for acute ankle sprain for physiotherapists is moderate

in the Netherlands: an observational study.

Aust J Physiother 2006;52:293–9. 10.1016/S0004-9514(06)70010-1Roebroeck ME, Dekker J, Oostendorp RAB, et al. .

Physiotherapy for patients with lateral ankle sprains. A prospective survey of practice patterns

in Dutch primary health care.

Physiother 1998;84:421–32.Ayanniyi O, Dosumu O, Mbada C.

Pattern and physiotherapy management of shoulder pain a 5-year retrospective audit of a

Nigerian tertiary hospital.

Med Sci 2016;5:12–26. 10.5455/medscience.2015.04.8321Johansson K, Adolfsson L, Foldevi M.

Attitudes toward management of patients with subacromial pain in Swedish primary care.

Fam Pract 1999;16:233–7. 10.1093/fampra/16.3.233Karel YHJM, Scholten-Peeters GGM, Thoomes-de Graaf M, et al. .

Physiotherapy for patients with shoulder pain in primary care: a descriptive study of diagnostic-

and therapeutic management.

Physiotherapy 2017;103:369–78. 10.1016/j.physio.2016.11.003.

The use of evidence-based practices for the management of shoulder impingement syndrome

among Indian physical therapists: a cross-sectional survey.

Braz J Phys Ther 2015;19:473–81. 10.1590/bjpt-rbf.2014.0115Struyf F, De Hertogh W, Gulinck J, et al. .

Evidence-Based treatment methods for the management of shoulder impingement syndrome among

Dutch-speaking physiotherapists: an online, web-based survey.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2012;35:720–6. 10.1016/j.jmpt.2012.10.009Artz N, Dixon S, Wylde V, et al. .

Physiotherapy provision following discharge after total hip and total knee replacement:

a survey of current practice at high-volume NHS hospitals in England and Wales.

Musculoskeletal Care 2013;11:31–8. 10.1002/msc.1027Barry S, Wallace L, Lamb S.

Cryotherapy after total knee replacement: a survey of current practice.

Physiother Res Int 2003;8:111–20. 10.1002/pri.279Moutzouri M, Gleeson N, Billis E, et al. .

Greek physiotherapists' perspectives on rehabilitation following total knee replacement:

a descriptive survey.

Physiother Res Int 2017;22 10.1002/pri.1671Naylor J, Harmer A, Fransen M, et al. .

Status of physiotherapy rehabilitation after total knee replacement in Australia.

Physiother Res Int 2006;11:35–47. 10.1002/pri.40Peter WF, Nelissen RGHH, Vliet Vlieland TPM.

Guideline recommendations for post-acute postoperative physiotherapy in total hip

and knee arthroplasty: are they used in daily clinical practice?

Musculoskeletal Care 2014;12:125–31. 10.1002/msc.1067Athanasopoulos S, Kapreli E, Tsakoniti A, et al. .

The 2004 Olympic games: physiotherapy services in the Olympic village polyclinic.

Br J Sports Med 2007;41:603–9. 10.1136/bjsm.2007.035204Beales D, Hope JB, Hoff TS, et al. .

Current practice in management of pelvic girdle pain amongst physiotherapists in

Norway and Australia.

Man Ther 2015;20:109–16. 10.1016/j.math.2014.07.005 10.1016/j.math.2014.07.005Bishop A, Holden MA, Ogollah RO, et al. .

Current management of pregnancy-related low back pain: a national cross-sectional survey of

UK physiotherapists.

Physiotherapy 2016;102:78–85. 10.1016/j.physio.2015.02.003 10.1016/j.physio.2015.02.003Bruder AM, Taylor NF, Dodd KJ, et al. .

Physiotherapy intervention practice patterns used in rehabilitation after distal radial fracture.

Physiotherapy 2013;99:233–40. 10.1016/j.physio.2012.09.003 10.1016/j.physio.2012.09.003Dekker J, van Baar ME, Curfs EC, et al. .

Diagnosis and treatment in physical therapy: an investigation of their relationship.

Phys Ther 1993;73:568–77. 10.1093/ptj/73.9.568Frawley HC, Galea MP, Phillips BA.

Survey of clinical practice: pre- and postoperative physiotherapy for pelvic surgery.

Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2005;84:412–8. 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00776.x

10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00776.xGrant M-E, Steffen K, Glasgow P, et al. .

The role of sports physiotherapy at the London 2012 Olympic Games.

Br J Sports Med 2014;48:63–70. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093169Haar GT, Dyson M, Oakley S.

Ultrasound in physiotherapy in the United Kingdom: results of a questionnaire.

Physiotherapy Practice 1988;4:69–72. 10.3109/09593988809159053Hurkmans EJ, Li L, Verhoef J, et al. .

Physical therapists' management of rheumatoid arthritis: results of a Dutch survey.

Musculoskeletal Care 2012;10:142–8. 10.1002/msc.1011Lineker SC, Hurley L, Wilkins A.

Investigating care provided by physical therapists treating people with rheumatoid arthritis:

pilot study.

Physiotherapy Canada 2006;58:53–60. 10.3138/ptc.58.1.53Murray IR, Murray SA, MacKenzie K.

How evidence based is the management of two common sports injuries in a sports injury clinic?

Br J Sports Med 2005;39:912–6. 10.1136/bjsm.2004.017624O'Brien VH, McGaha JL.

Current practice patterns in conservative thumb CMC joint care: survey results.

J Hand Ther 2014;27:14–22. 10.1016/j.jht.2013.09.001Peterson M, Elmfeldt D, Svärdsudd K.

Treatment practice in chronic epicondylitis: a survey among general practitioners and

physiotherapists in Uppsala County, Sweden.

Scand J Prim Health Care 2005;23:239–41. 10.1080/02813430510031333Peterson ML, Bertram S, McCarthy S, et al. .

A survey of screening and practice patterns used for patients with osteoporosis in a sample

of physical therapists from Illinois.

J Geriatr Phys Ther 2011;34:28–34. 10.1519/JPT.0b013e31820aa84dRushton A, Wright C, Heap A, et al. .

Survey of current physiotherapy practice for patients undergoing lumbar spinal fusion

in the United Kingdom.

Spine 2014;39:E1380–E1387. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000573Sran MM, Khan KM.

Physiotherapy and osteoporosis: practice behaviors and clinicians’ perceptions—a survey.

Man Ther 2005;10:21–7. 10.1016/j.math.2004.06.003Tomkins CC, Dimoff KH, Forman HS, et al. .

Physical therapy treatment options for lumbar spinal stenosis.

J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2010;23:31–7. 10.3233/BMR-2010-0245Williamson E, White L, Rushton A.

A survey of post-operative management for patients following first time lumbar discectomy.

Eur Spine J 2007;16:795–802. 10.1007/s00586-006-0207-8van der Windt DA, Koes BW, de Jong BA, et al. .

Shoulder disorders in general practice: incidence, patient characteristics, and management.

Ann Rheum Dis 1995;54:959–64. 10.1136/ard.54.12.959Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Ostelo R, Kim Burton A, Waddell G.

Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Low Back Pain in Primary Care:

An International Comparison

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001 (Nov 15); 26 (22): 2504–2513Dawda P.

CareTrack: assessing the appropriateness of health care delivery in Australia.

Med J Aust 2012;197:548–9. 10.5694/mja12.11149McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. .

The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States.

N Engl J Med 2003;348:2635–45. 10.1056/NEJMsa022615Zadro JR, O'Keeffe M, Maher CG.

Evidence-Based physiotherapy needs evidence-based marketing.

Br J Sports Med 2019;53:528–9. 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099749Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

National health expenditures

2017 highlights. Available:

https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-

reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nationalhealthaccountshistorical.html

[Accessed 18th Mar 2019].American Physical Therapy Association (APTA)

Vision statement for the physical therapy profession and guiding principles to

achieve the vision.

Available: http://www.apta.org/Vision/

[Accessed 20th Feb 2018].da Silva TM, Costa LdaCM, Garcia AN, et al. .

What do physical therapists think about evidence-based practice? A systematic review.

Man Ther 2015;20:388–401. 10.1016/j.math.2014.10.009Derghazarian T, Simmonds MJ.

Management of low back pain by physical therapists in Quebec: how are we doing?

Physiother Can 2011;63:464–73. 10.3138/ptc.2010-04PChoosing Wisely An initiative of the ABIM Foundation. Available:

http://www.choosingwisely.org/ [Accessed 20th Feb 2018].Kulkarni RN, Gibson JA, Brownson P, et al. .

Subacromial shoulder pain BESS/BOA patient care pathways.

Shoulder Elbow 2015;0:1–9

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return to WORKERS' COMPENSATION

Return to CLINICAL PREDICTION RULE

Return to CHIROPRACTIC CARE FOR VETERANS

Since 3-27-2020

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |