“I Stay in Bed, Sometimes All Day.” A Qualitative Study

Exploring Lived Experiences of Persons with

Disabling Low Back PainThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2020 (Apr); 64 (1): 16-31 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Sharli-Ann Esson, BSc, MHScm Pierre Côté, DC, PhD, Robert Weaver, MA, PhD, Ellen Aartun, MSc, PhD, Silvano Mior, DC, FCCS(C), PhD

Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College,

6100 Leslie St.,

Toronto, Ontario, M2H 3J1

Aim: To explore the lived experiences of persons with low back pain (LBP) and disability within the context of the International Classification of Function, Disability and Health (ICF) framework.

Methods: Qualitative study using focus group methodology. We stratified LBP patients into two low (n=9) and one high disability (n=3) groups. Transcriptbased thematic analysis was conducted through an interpretivist lens.

Results: Four themes emerged: Invisibility, Ambivalence, Social isolation, and Stigmatization and marginalization. Participants described how environmental factors affected how they experienced disability and how their awareness of people’s attitudes affected personal factors and participation in social activities. High disability participants experienced challenges with self-care, employment, and activities. The invisibility of LBP and status loss contributed to depressive symptoms.

Conclusion: LBP patients experience physical, social, economic and emotional disability. Our findings highlight the interaction between domains of the ICF framework and the importance of considering these perspectives when managing LBP patients with varying levels of disability.

KEYWORDS: low back pain, disability, biopsychosocial model, ICF framework, qualitative research

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Lower back pain (LBP) is a leading cause of disability worldwide. [1, 2] It is one of the most prevalent chronic disorders and imposes a substantial economic burden globally. [3] Approximately 80% of adults will experience LBP at some point in their lives. [1] LBP manifests itself as stiffness, tension or achiness confined between the costal margin and the inferior gluteal folds; with or without sciatica. [4] The pathophysiological causes of LBP are often unidentifiable. [5] This creates challenges to its effective treatment and management, especially because patients experience LBP in different ways. [6] Others suggest that this unidentifiable pathology along with unclear diagnoses and often the lack of visible proof can cause LBP sufferers to be labeled as hypochondriacal, malingerers and even mentally ill. [7–9] This may lead to disbelief or a dismissal of the seriousness and authenticity of disability associated with LBP. [10, 11]

In addition to the physical effects experienced by LBP patients, there are personal, societal and psychological ramifications associated with the condition. [5, 12] In some cases, asocial behaviour and negative self-image are additional consequences of living with LBP. [13] Furthermore, increased work absenteeism, lower productivity, status loss, and depressive symptoms often accompany chronic LBP. [1, 14] However, limited qualitative data is available which describes LBP patients’ daily experiences with LBP associated disability from a biopsychosocial perspective. [12, 15, 16] Thus, it is important to understand the everyday lived experiences of people with LBP and explore how psychosocial factors impact pain and disability, in order to effectively address them in their care plan.

The ICF Framework

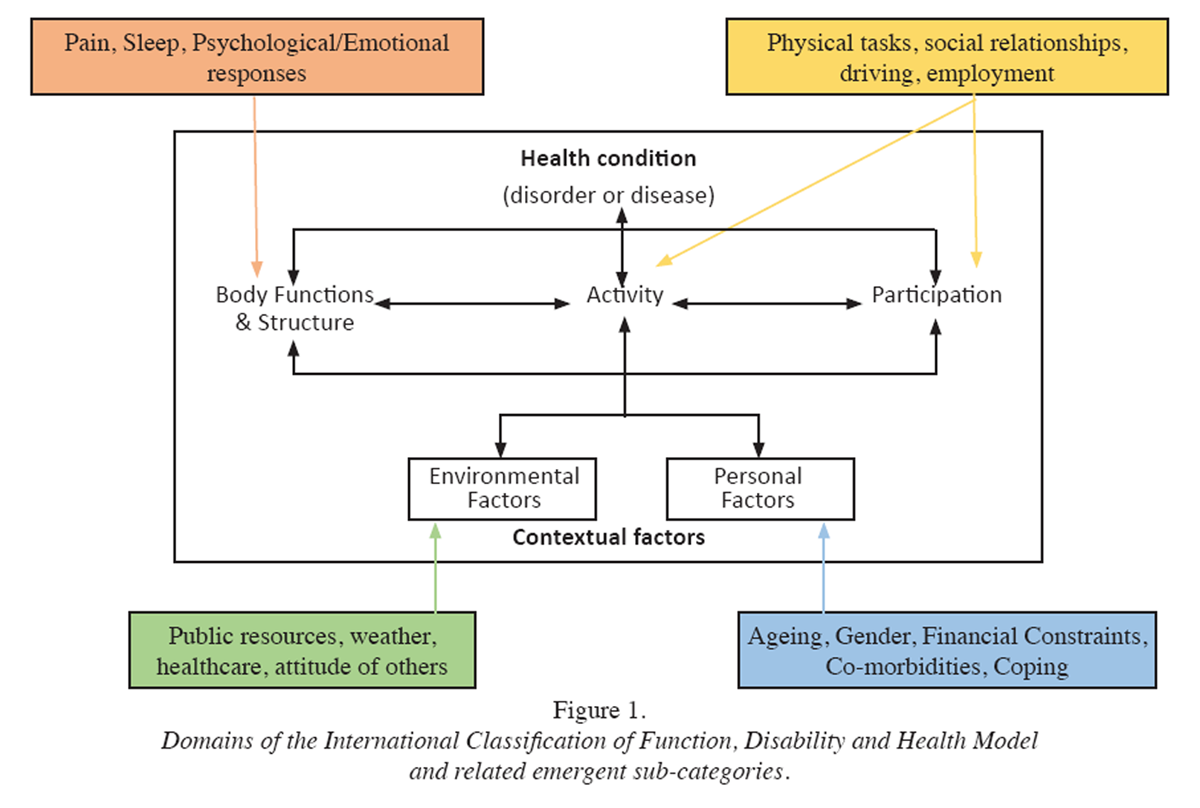

Figure 1 In consideration of the biopsychosocial attributes of LBP, we framed our qualitative study using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework as a point of reference for our data collection. [17] The ICF is helpful to conceptualize the positive and negative aspects of functioning from a biological, individual, and social perspective. [17] The framework emphasizes the role of the environment by stressing the importance of understanding the context in which the person lives and its interactions with health conditions and personal factors.

The ICF includes five interacting domains:i) body functions: physiological functions of body systems (including psychological functions);

ii) body structures: organs and limbs;

iii) activity: execution of a task or action (including cognitive functions);

iv) participation: involvement in a life situation; and

v) environmental factors: physical, psychological, social, and attitudinal environment in which people live (barriers to or facilitators of functioning) (Figure 1).The ICF framework is the international reference for the conceptualization and evaluation of disability. [17] It is in line with the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and provides a common and universal language to understand disability and human functioning across communities. [18, 19] The ICF framework provides a structured guide for the conceptualization, collection and organization of data necessary to arrive at a comprehensive understanding of an individual’s lived experience, within the context of their health condition. Because disability denotes “the negative aspects of the interaction between an individual (with a health condition) and that individual’s contextual factors” [17] a clinician engaged in patient care must seek to understand the individual’s environmental and personal factors, if appropriate care is to be delivered.

We used the ICF framework to guide our analysis and address our objective of exploring the lived experiences of persons with low back pain and disability. Our study is part of an international, collaborative project between the Ontario Tech University and the ICF Research Branch (a cooperation partner within the WHO Collaborating Centre for the Family of International Classifications in Germany at the German Institute for Medical Documentation and Information (DIMDI)). The aim of this international collaborative project is to identify the aspects of functioning that are most important to participants and subsequently develop an ICF assessment schedule, a standardized measurement instrument, specifically designed for manual medicine for the reporting of functioning. Our study investigates aspects of functioning among patients with LBP in Ontario, Canada.

Materials and Methods

Study design

We used a qualitative design to explore the everyday experiences of persons with LBP. We used Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), situated within the interpretivist paradigm, to understand participants’ experiences. IPA reveals complex and dynamic relationships and places value on the subjectivity of participants’ experiences. [13]

We used focus groups to elicit these everyday experiences. Focus groups offer a forum that enables participants in similar circumstances to share their experiences, and often facilitate disclosure of additional and more nuanced responses regarding their own experiences. Focus groups provide richness in the data that reflects the synergy between participants and explores their perceptions of an issue. [20] Ethics approval was obtained through the Research Ethics Boards of Ontario Tech University (REB # 14050) and CMCC (REB # 1629014).

Participants and recruitment

Participants were recruited from three Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College (CMCC) teaching clinics in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) in Ontario, Canada. Participants were eligible to participate if they met the following criteria: 1) 20–65 years of age; 2) reported LBP; 3) were receiving chiropractic care for their LBP; and 4) spoke English.

Participants were recruited through advertisements placed in clinic reception rooms and by clinicians informing their patients about the study. CMCC staff clinicians introduced the study to patients and identified interested patients. The first author contacted interested patients and provided them with study information and the informed consent package. Focus groups were scheduled at the convenience of participants. Each focus group was conducted in a private room within the clinic, and situated in a convenient location for participants.

Focus group allocation

We used the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS) to stratify participants into low disability focus groups (LDFG) and high disability focus groups (HDFG). The WHODAS is a 12–item, self-administered questionnaire designed to assess difficulty experienced doing regular, everyday tasks. [21] The WHODAS is directly derived from the ICF and evaluates six domains of disability the “activity and participation” dimension of the ICF: cognition; mobility; self-care (hygiene, dressing, eating & staying alone); getting along (interacting with other people); life activities (domestic responsibilities, leisure, work & school); and participation (joining in community activities).

The WHODAS is considered to be a valid and reliable measure of disability and thus was appropriate for stratifying our sample. [22, 23] The WHODAS is useful to measure disability in chronic low back pain patients and significantly positively correlated with the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 item, the Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain-Revised, the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) and the Opioid Risk Tool (ORT). [24] We used a pre-determined cut point of 36 out of a possible 60 points to allocate participants into LDFG and HDFG. A score above 36 is suggestive of a person having higher levels of disability severity. Previous studies used similar methods of stratification using this questionnaire. [25–27]

We anticipated recruiting 32 participants, with eight people in each of 4 groups, with an equal distribution of male and female participants. However, we presumed difficulty in recruiting equal distributions due to clinic population and would accept a 5:3 ratio of participants in each focus group.

Data collection

We used a script to guide questioning of participants. The focus group interview script was designed to elicit responses related to the ICF framework. Further probative questions explored answers to the questions in the event that what was said was not understood or required further clarification (Appendix 1). The script was reviewed in advance by the research team and pretested in a sample focus group to ensure clarity and comprehension. Each focus group was led by a trained facilitator (SE) and assisted by a co-investigator (EA). Focus groups were scheduled at different times to accommodate participants availability. The focus groups lasted approximately 90 minutes each.

Each session was audio-recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim with participants’ consent. The recordings were transcribed by an experienced transcriptionist. Each transcript was checked for accuracy by cross referencing the audio file with the transcribed document. Errors in content and sentence structure were corrected and extraneous sounds/comments noted. Finally, confidentiality of statements made by each focus group participant in transcripts was assured by providing pseudonyms. Transcripts were not returned to participants for review.

Analysis

We used the NVivo11 Software (QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 11, 2015) to organize and analyze the transcripts. There was broad agreement among team members regarding the essential meaning of the core elements of the ICF framework. The framework became part of the scaffolding used during the coding process. These elements provided the foundation for our thematic analysis, where emergent themes were identified and conceptually expanded.

The first author imported transcripts into NVivo software and reviewed, identifying, organizing, and coding key passages in NVivo nodes. Team members discussed and resolved ambiguities in the coding process as they arose and until consensus was reached. Once agreement was reached coded nodes were linked to components of the ICF framework. The framework was used to scaffold themes emerging from the data. Once preliminary themes were identified, the team further discussed how they interrelated within the context of the ICF framework until consensus was reached regarding the soundness of the emergent themes.

Results

Table 1 We enrolled twelve participants in the study – seven women and five men, who participated in one of three focus groups. The two LDFG included five and four participants, respectively. The HDFG included three participants. In addition to their varying degrees of disability, participants also had varying ages, ethnicities, and socioeconomic backgrounds, including students, employed, unemployed and retired individuals (Table 1).

ICF Domains

Based on the five a priori domains from the ICF framework, participant experiences were coded accordingly. Our findings suggest that the domains of “activity” and “participation” bear similarities that make it difficult to distinguish between them. Similar findings have been also reported by others [28–30]; therefore, we merged these two domains (Figure 1).

Body Function and Body Structure

Participants described various challenges associated with body structure and body function. These included the exacerbation of, difficulties sleeping and varied emotional responses stemming from their condition and pain. In both the low and high disability focus groups, participants provided conflicting accounts about the location of their pain. Some participants suggested that their LBP was confined to one area – typically the small of the back, while others explained that their pain was not localized but rather travelled from one area to the next, making it difficult to predict when or where the pain would arise.“When I first started getting the pain I would say it was somewhat localized and then it started spreading and now I can’t even tell the difference anymore because it is throughout my entire body.”

Allan [HDFG3]Difficulty falling asleep and interrupted sleep are common experiences amongst persons living with disability. [31] Participants in the LDFG reported falling asleep was not difficult but they struggled to sleep restfully or remain asleep, often having to change positions to relieve their pain or discomfort:

“For me I have really rough nights sleeping so like every hour or so I have to wake up and stretch and move around. So, in the morning the same thing, it is about a half an hour of stretching and moving around before I can actually function.”

Corrina [LDFG1]In contrast, HDFG participants reported struggling not only with falling asleep but remaining asleep. Allan’s account clearly exemplifies these challenges.

“I would say both because it is almost impossible to find a comfortable position where you say, ‘OK I am not in pain in this position so I will stay here.’ You find yourself tossing and turning all night long trying to find a position that works and usually you don’t and 9 times out of 10 the only reason you do fall asleep is from restlessness.”

Allan [HDFG3]Participants described how their LBP negatively impacted their motivation to perform daily activities. Emotional responses and concentration on daily tasks varied by participant group. While LDFG participants experienced few challenges with concentration or maintaining focus, the HDFG participants described a significantly diminished ability to concentrate, having to work much harder than before:

“…I also have a hard time concentrating. So, my concentration when it comes to studying doesn’t last more than like 10–15 minutes. So I have to study in like 10–15 minutes fighting to read and then break 5 minutes… before I would just go to class listen and barely have to study anything or read too much now I find myself doing 10 times more work just to get one section over with.”

Allan [HDFG3]Activity and participation

There were marked contrasts among the participants in the ability to engage in physical actions, which affected their social relationships, driving and employment. Participants in the LDFGs expressed few activity limitations. They were able to differentiate between activities they could manage and those seen as detrimental to their ability to function. Unlike the HDFG participants, the LDFG participants reported being better able to manage their pain by modifying, rather than limiting, their activities. Many enjoyed cycling, yoga and swimming, but avoided high intensity exercises such as running, which they maintained placed severe pressure on their back and legs/knees.“I went to a trampoline park with my friends…I had to completely stop because of pain in my neck, pain in my back…and I’m like well I’m going to watch you guys…because you know you can’t really do the same level as they can...”

Leo [LDFG2]Conversely, the HDFG participants struggled with even elementary body movements and body positions, and described serious exercise restrictions:

“Lying flat is very, very painful. Bending down like as the day progresses the worse I get and by the end of the day it is nearly impossible to function.”

Helena [HDFG3]Participants in the HDFG noted that their chiropractors recommended exercises to manage their LBP but felt the chiropractor did not understand the challenges they faced in doing the exercises. This is an example of the dissonance between LBP patients and their healthcare providers which may impact their compliance. [32]

“It limits your ability to do things especially exercise. So, it seems like everybody where you go for treatment recommends exercise but they kind of don’t understand that it is very hard to do things, especially when you squeeze, the pain just intensifies times 50.”

Allan [HDFG3]Most LDFG participants suggested their condition did not negatively impact their social interactions. In contrast, participants in the HDFG described a more dramatic change in social relationships, which included loss of friends and the desire to socialize. These findings are typical of persons living with severe back pain and supports findings in previous literature. [13, 36, 37]

“I just don’t return calls if they call. I don’t think they understand, they don’t understand what you are going through.”

Francine [HDFG3]The employment status of persons in the LDFGs varied and included retired persons, unemployed persons, students and working persons. Those who worked were aware of their physical capabilities and sought employment accordingly:

“I can’t really do certain physical jobs because I am not sure if it is going to tighten up…So I try to stay away from anything like that. The problem is a lot of jobs are going to still require standing anyways.”

Leo [LDFG2]HDFG participants reported fewer employment opportunities compared to those in the LDFG. All HDFG participants were unemployed. For one participant, it was a personal choice to become full-time caregiver for a loved one. Another participant was no longer able to assume the labour-intensive demands of their work. Yet another participant quit her job because other co-workers assumed her compensatory movements and gait were related to her being intoxicated. HDFG participants expressed a desire to return to work but noted their LBP prevented them from long periods of sitting and standing. They viewed seeking new employment as a challenge, fearing the potential employers’ reactions after disclosing their LBP.

“It is also hard to try and get another job…So when I go and try and get jobs I would rather be honest…When you say those kinds of things to people about how you really are, it is like OK, right away you look at their face and you’re like ‘I know I didn’t get this job.”

Allan [HDFG3]Environmental factors

Environmental factors that impacted participants included public resources, healthcare and the attitudes of others. Communal spaces and transit were the primary public resources discussed by participants. Many of the participants in the LDFG lived within the downtown core and took advantage of the many available community resources:“They will also fall-proof your house. So that is one of the things that you can get, you have to have a doctor referral to it but they will come in and look at your house and how you have it set-up and then do the fall prevention.”

Walter [LDFG1]Participants in the HDFG, who also lived in the downtown core, were significantly less informed about community resources. They knew that some resources were available online but struggled to access them because they did not own a computer, were unaware how to access, or could not afford some resources. A student in the HDFG described classroom design, uncomfortable seating and poor accessibility as a barrier to attending classes. They also noted that although campus buildings were equipped with handicap push buttons to automatically open doors, many simply did not function:

“At my school I would say about 75% of the handicap buttons don’t work and if they do work maybe it is only in the summer time because in the winter they get jammed.”

Allan [HDFG3]Participants with HDFG relied on elevators or escalators to get to higher floors in multi-story buildings. Where neither were available, they relied heavily on the handrails of the stairs:

“So every time I walk into a building I always like to know where the elevator is or escalator or some easier way to get up and if the last resort is the stairs then I have to kind of coach myself into doing it...”

Allan [HDFG3]Public transit was reported as a significant concern among most participants. Buses and streetcars were the most frequently used modes of transportation amongst participants. Participants in both groups expressed caution and care when moving on and off buses and streetcars. The physical design of the vehicles made travel difficult for participants. One participant suggested that bus seats provided no back support and aggravated their pain:

“Yes, their seats are really bad for people with lower back pain. It is like sitting on a metal plate.”

Allan [HDFG3]Participants also described experiences with other transit users, ranging from being helpful by offering a seat to flat-out dismissive. Participants experienced feelings of frustration as their disability often went unnoticed, with few fellow passengers understanding their pain and functional impairment. Whether in interactions with family members or with persons on a bus, LBP sufferers often encounter others’ disbelief of their disability – if they appear fine on the outside, they must be fine on the inside too. [33] Since they “look good” and appear to be able-bodied and fully functional, participants felt their pain was misunderstood and delegitimized.

All participants sought treatment from general practitioners and chiropractors. Participants in both low and high disability focus group were pleased with the treatment they received in the chiropractic clinic. A few participants detailed the empathetic and understanding nature of their chiropractor and positive outcomes of care:“Actually, my chiropractor now is actually having me…stand straight and you move your hips forward, like a tilt kind of thing, and that’s how you walk and it’s amazing. The pain is much less over a fairly long period of time you can actually walk properly.”

Mallory [LDFG2]

“I do like when the chiropractor does work on me. Basically, they stretch it out first and then put menthol or whatever stuff they put on it. Like this morning I was there and I find that I can move around a lot better once they do that.”

Helena [HDFG3]In addition to chiropractic treatments, participants in the LDFGs were more actively involved in their care and encouraged interprofessional correspondence between those involved in their treatment, including the fitness expert at the gym. HDFG participants were mindful of what they were feeling so they could appropriately articulate them to their chiropractors. Participants also said their chiropractors made suggestions about strategies or equipment they might use to cope with various everyday challenges.

A unique and interesting finding about participants attending for chiropractic care was their opportunity to interact with others in the waiting room. Some participants did not have healthy social lives and seemed to appreciate the friendly environment in the clinics. They often treated their chiropractic appointments as a part of their social calendar.“Some people that go to the bar and they drink and try to get rid of their stress which actually makes things worse and to socialize. Believe it or not…I actually get a bit of a high in coming in from my treatment. So I am getting the medical help and it is also a social structure too.”

Mason [LDFG2]The attitudes of friends, family and the general community were important to all participants. However, there was a disparity between the groups. Participants in the LDFG shared varying experiences about the attitudes of family members and community members. Some reported that healthy family and social relationships did not much differ from when they did not have LBP.

“Yes mine hasn’t affected things that much with getting together with friends and that, so I am lucky …”

Wendy [LDFG2]Conversely, participants in the HDFG saw living with LBP as the reason why they experienced daily personal strife. They believed their LBP led to the decline of relationships. They felt their friends and family did not understand what it was like to live with LBP and were often reluctant to discuss the pain they experience, and instead would steer conversations away from pain and disability or even distancing themselves from others.

“I find that people say they will be there for you, they are your friends or whatever and even family, and all of a sudden there will be days or times when I need somebody for even emotional support or physical support to do something, and everybody is busy or they don’t want to come or they don’t want to hear about it.”

Helena [HDFG3]HDFG participants implied their LBP was wholly responsible for their inability to work or effectively function in social settings. As has been reported elsewhere [13], respondents also were made more aware of their disability when in the presence of those who have not experienced back pain, and they worried about how others perceived them.

Personal Factors

Personal factors that affect participants included age, co-morbidities, and financial constraints; gender impacted frequency of activity. Ageing and comorbidities affected participants’ differently. HDFG participants did not perceive that age impacted their level of disability but felt their comorbidities did. In contrast, LDFG participants were less affected by their co-morbidities and questioned whether their experiences with disability were a result of normal ageing processes rather than LBP:“I think my emotional state is just understanding that this is a 51–year-old body that has gone through a lot of sports and athletics and knocks and bruises and stuff like that.”

Val [LDFG1]Financial constraints were a recurrent theme among HDFG but not so in the LDFG participants. HDFG participants’ primary concern was with the cost of engaging in certain activities or using resources such as a gym. Instead they emphasized the need to satisfy basic needs such as securing healthy food and shelter.

“Eating is expensive… You buy what is healthy and what is on sale and you try to eat healthy... they say with the inflammation you have to watch what you eat… you have to watch dairy and gluten and all that stuff but again they are expensive stuff.”

Francine [HDFG3]Self-management was the primary coping mechanism for participants in both low and high disability groups. It allowed them temporary relief from their LBP and gave them the opportunity to function more adeptly in everyday situations. They used various temporary modalities to alleviate their pain such as hot/cold packs, topical pain-relieving creams and painkillers. A few participants also mentioned that they found deep breathing exercises and meditation to be effective. Other enablers to functioning included developing creative self-management techniques and interacting with other LBP patients. One participant in the HDFG decreased the discomfort she experienced when travelling on public transit by carrying a backpack stuffed with soft items (scarves, clothes etc.) and used it as a cushion to ease the pressure on her back. Another participant said that receiving advice from other LBP patients and learning about different coping strategies improved her ability to function.

“Hearing what other people are doing, I think community support is a big thing, because everybody knows one piece of the puzzle but nobody knows the whole puzzle.”

Corrina [LDFG1]Interrelated themes

Due to the interrelated nature of the ICF domains, we identified four emergent themes that recurred across all the focus groups and were interwoven among the domains. We summarized participant responses within these respective themes as: Invisibility, Ambivalence, Social isolation, and Stigmatization and marginalization.

Invisibility

Since chronic LBP is not physically visible, non-sufferers often do not validate that the condition is real to sufferers. [23] For example, some participants described the attitudes of transit operators who did not recognize their disability, while using public transportation. They expressed concern that operators often maneuvered buses in a less than smooth manner and often accelerated into traffic before they were seated or in a secure standing position. Corrina recounted her experience using transit buses:“They will put the ramp down but they are not going to put it down for someone who ‘looks good’”

[LDFG1].A participant in the HDFG described an encounter while using public transportation, where another passenger asked her to surrender the accessible seat she was occupying to another passenger who appeared to need it. Participants reported feeling frustrated by the lack of recognition of their disability. Even when LBP sufferers tried to explain their symptoms to others, non-LBP sufferers often failed to recognize or believe the suffering and functional impairment of LBP sufferers. Whether through interactions with family members or strangers, the pain and disability LBP sufferers endure remains invisible. Their pain is not viewed as legitimate because they often appear to be able-bodied and fully functional.

Ambivalence

Participants in the HDFG seemed to display feelings of ambivalence about how to live with LBP. They seemed to grapple with whether to accept that they might be less able to do some things they were previously capable of doing or to attempt to normalize their current situation, despite possibly requiring special consideration. Some used assistive devices to improve functioning. However, all participants in the HDFG were adamant about only using these devices temporarily as they strived to maintain their independence.

Helena noted,“I can do without any of those devices. I am better off because once you start using them, it is a crutch and basically your muscles and whatever further deteriorates because you are not using them… My independence with that is no good”

[HDFG3].Some participants reported refusing to use certain assistive devices altogether such as wheelchairs and walkers as they perceived them as symbols of disablement, choosing not to announce their disability to others. This is consistent with previous studies suggesting persons with disabilities often abandoned the use of assistive devices to avoid the judgement of others and prevent their potential social exclusion. [34, 35]

Despite lamenting that others often did not recognize their disability, participants were nonetheless concerned about appearing disabled and the accompanying perceived loss of social status. This contradiction illustrates an internal struggle that LBP patients must manage as they try to renegotiate and redefine the self to accommodate for lost capabilities.

Social isolation

The theme of social isolation spanned many domains of the ICF framework, reflecting the psychological, relational and emotional aspects of LBP sufferers. The emotional toll chronic LBP had on participants negatively impacted their motivation to perform daily activities. Depressive symptoms sometimes lead participants to withdraw and retreat to their homes for extended periods of time. [28] Participants described behavioural changes such as loss of self- esteem and social isolation that resulted from feelings of depression. Both LDFG and HDFG participants felt emotionally drained and disliked being dependent on others and assistive devices. In particular, participants in the HDFG felt especially overwhelmed and withdrawn and wanted to avoid the reality of their current situation. Francine stated,“I stay in bed, sometimes all day which is even worse for the back pain… but if you don’t want to get out, you don’t want to get out…”

[HDFG3].This withdrawal offers some relief from having to defend or explain a condition, which others may not acknowledge or understand. [29]

Across the focus groups, participants expressed varying experiences related to social relationships. Most LDFG participants suggested that their condition did not negatively impact their social interactions; however, they did acknowledge small changes in their relationships. For example, one participant identified a change in the interests she previously shared with friends. When the interests were no longer shared, friendship ties became frayed:“I mean I had work friends but only at work. Once you leave work, they go home you know and didn’t really have time to talk…My friends are not interested in what I want to do ok so I would like to see people more interested in what I want to do and I will join them”

[Corrina, LDFG1].Their accounts illustrate the strain on relationships that can occur when the primary subject of conversation revolves around chronic pain and may eventually become bothersome to friends, who may not understand this pain. Respondents felt that friends sometimes shied away from them to avoid such conversation or interaction.

In contrast, participants in the HDFG described a more dramatic change in social relationships, which included loss of friends and loss of the desire to socialize.

Allan notes,“You will probably lose all your friends, they will become tired of always having to lag behind”

[HDFG3].Francine illustrates the lost desire to socialize and the perceived dissonance been LBP sufferers and non-sufferers:

“I just don’t return calls if they call. I don’t think they understand, they don’t understand what you are going through”

[HDFG3].These changes appear consistent with persons living with severe back pain. [13, 36, 37]

Stigmatization and marginalization

Stigmatization, and the marginalization that often accompanies it, became apparent in the focus groups as participants discussed their physical activities as well as employment, or lack thereof. Employed participants in the LDFG were aware of their physical capabilities and limitations, and sought employment within these confines:“If I am looking for work I can’t really do certain physical jobs because I am not sure if it (his back) is going to tighten up… So I try to stay away from anything like that”

[Leo, LDFG2].Unlike their counterparts, participants in the HDFG described considerably fewer employment opportunities. At the time of the focus group session, all participants in the HDFG were unemployed. Some expressed a desire to return to work but noted that their LBP caused diminished sitting and standing capabilities. The idea of seeking new employment became a challenge, as participants feared the reaction of potential employers once they disclosed their condition:

“It is also hard to try and get another job…So when I go and try and get jobs I would rather be honest… When you say those kinds of things to people about how you really are, it is like OK! Right away you look at their face and you’re like ‘I know I didn’t get this job”

[Allan, HDFG3].When asked about what would enable them to function in the workplace, participants in the HDFG said that it was important for employers to be empathetic towards their need for frequent breaks. They feared that their LBP would not be recognized and that employers might think they did not take their jobs seriously.

The discomfort, shame, and stigma associated with the negative responses of others towards LBP sufferers has also been directly linked to depressive symptoms and isolated behavior. [10] Some participants felt that family members had other concerns and chose not to discuss their LBP. In this regard, the disinterest of family members caused feelings of marginalization.

Val noted,“…you are at the dining room table with your family, there is always other people’s issues that are more important and more pressing kind of thing, than just ‘oh, you just have lower back pain; Whatever!”

[LDFG1].This finding supports previous work by Smith and Osborn13 who found that social situations often intensified the psychological dilemma faced by LBP patients as they become self-conscious and are fearful of the judgement of others.

Discussion

Our findings suggested both commonalities and divergence between LDFG and HDFGs. The ICF conceptualizes activity and participation as two distinct categories. However, numerous researchers have argued that the domains of activity and participation within the ICF model are difficult to distinguish. [30–32] Our findings suggest these two domains bear many similarities and often supplement each other. Therefore, the domains of activity and participation were merged and reported together to show individual limitations and the resulting restrictions that LBP patients experience.

The ICF framework and its diverse domains enabled us to capture an array of experiences identified by LBP sufferers in LDFGs and HDFG. Persons in the LDFGs had higher levels of functionality but living with LBP required them to modify several of the activities of daily living. Further, they demonstrated increased awareness of the events and activities they could and could not safely and easily participate in. In most low-disability cases, familial relationships and friendships were only minimally affected. Nonetheless, several participants expressed some emotional responses and depressive symptoms which they associated with living with LBP.

HDFG participants also experienced emotional challenges living with LBP, but their social isolation and depressive symptoms appeared to be more extreme. Their physical abilities were more diminished and there was evidence of some fear avoidance behaviour. Their interpersonal relationships with family and friends were significantly strained and, in some cases, completely severed. Participants in the HDFG showed a greater proclivity toward social isolation as a result. They also demonstrated a heightened sensitivity toward and awareness of how their illness was perceived by others and how people behaved toward them. They felt they were no longer able to maintain social relationships or carry out gainful employment. These experiences support findings by Walker [29] who developed the theme of loss in their article. Our participants reflected upon the physical, social, and economic losses that may occur as a result of high levels of disability associated with LBP. [12]

Public transportation was a major topic of conversation in our focus groups. Most participants agreed that many of their experiences using public transportation were unpleasant and this provided a clear example of the challenges that LBP sufferers face as a result of living with an invisible condition. The uncomfortable seating and less than smooth rides had physical consequences for LBP patients. However, previous literature has focused primarily on the LBP in transit operators rather than passengers, suggesting that drivers’ seats needed to be ergonomically evaluated and adjusted accordingly. [41] Our data suggest an equally important need is to also assess and evaluate the passengers’ perspective. A significant portion of the experiences described by the participants pertain to the effects of environmental and personal factors as articulated in the ICF model.

Previous quantitative studies suggest LBP sufferers are subjected to loss of employment, social identity and inequality; experience isolationism, depression, distressing experiences; as well as pain, disability and low well-being. [3, 5, 13] However, there are fewer qualitative studies exploring the in-depth understanding of patients’ pain experiences with LBP. [13, 28] A recent systematic review identified three overarching themes emergent from 28 qualitative studies on chronic LBP: impact on self; relationships with family and friends, and health providers and organizations; and coping. [13, 28]

Yet, few of the included the qualitative studies assessed the effect of age, gender, physicality, temporality and disability on patients’ experiences. Our study adds to this gap in the literature by having stratified our focus groups into low and high disability. The two groups described similar experiences, though their salience and consequences varied considerably. This offers an important first step toward understanding the experiences and impact of different levels of LBP and disability. Future research should go beyond the binary distinction used here, to explore how more subtle differences in levels of LBP and disability affect experiences and behaviours of those afflicted.

Our findings confirm that disability associated with LBP has multiple and often simultaneous effects. [42] For example, participants indicated that physical pain contributed to their inability to complete activities or participate in events which in turn influenced people’s attitudes towards them, friendships, and sense of isolation. This supports the reported direct interaction between body function, activities, participation, and environmental factors of the ICF model. [43]

Our findings highlight the benefits of using a biopsychosocial model, specifically the ICF model, to interpret our data. Our findings support the connections among the domains of the ICF model as manifested in the lives of those afflicted with LBP. The feedback loop between the domains in the framework is reflected in the description of participants’ lived experiences in our study. Our findings support the contention that personal factors influence the other domains and humanizes the ICF framework by valuing and respecting the uniqueness of the person. [11, 43] Thus, our study adds to the paucity of literature assessing the potential utility of the ICF in clinical settings.

Strengths and limitations

The use of the ICF framework is a major strength of our study. Its expansive framework has been shown to be useful and generalizable in a variety of scenarios and is applicable to other health conditions and disabilities. [23] Additionally, the connections between our data and data previously collected in other studies that also utilized the ICF framework affirms our decision to use this model. [44] Other strengths of our study relate to our focus on eliciting participants’ everyday experiences living with LBP. We recruited participants with varying demographic profiles and low and high levels of disability. The qualitative approach encouraged participants to share freely and the results are likely to be clinically applicable.

There were limitations in the study as well. First, despite efforts to recruit participants and extend data collection period, we were unable to achieve our predetermined sample estimate per focus group. Second, we were unable to represent fully the similarities and differences between employed and unemployed participants, as most focus group respondents were unemployed, which may suggest that employed people have less time to participate in focus groups. Third, we were only able to conduct one high disability focus group. Our results showed that LBP patients with high disability experienced greater restriction in mobility (transportation), which could be an indication that attending focus groups was more difficult for these persons. We suggest that further research be conducted in this regard. Fourth, the limited age distribution of participants impacts our ability to interpret their lived experiences. Fifth, the sample only captured the perspectives of chiropractic care seekers, and may under-represent LBP sufferers with sub-clinical symptomology, or who seek traditional medical care or no care at all. Finally, we crudely differentiated subjects into low and high disability groups that may not account for more subtle distinctions with regard to LBP severity. Further research might include a middle group to help detect more subtle differences with regard to LBP severity.

Significance / implications

Our study raises awareness about the importance of environmental and personal factors in the ICF framework and their unique interaction with, and influence on persons’ lived experiences. This information facilitates clinicians by encouraging them to consider these factors in their understanding of their patients’ disability and modifying their management strategies.

Also, our data contributes an important component to an international, collaborative project by providing a unique local Canadian perspective of how LBP patients experience disability. We were able to determine some of the environmental and personal factors on the ICF framework, which LBP patients describe as affecting their disability and functioning. The data will complement qualitative data collected in Norway and Botswana. Using similar qualitative methodology, the data collected from different regions make it possible to access results across cultures and nations, strengthening the ability for regional and cultural comparisons. This will aid in the creation of a standardized assessment tool which will contribute to improved patient centered models of care and facilitate clinicians’ ability to better assess and document disability in LBP patients within the context of the ICF framework.

Conclusion

Our study supports the notion that LBP is associated with varying social and psychological consequences in sufferers’ daily lives that may not be assessed, documented nor addressed in their clinical care. The ICF framework addresses the often-overlooked social factors of the biopsychosocial model but also includes the impact of environmental and personal factors. The findings of our study support the need to measure and address important social factors, often underrepresented in previous work. [45, 46] Furthermore, our findings highlight the inherent interrelatedness of the dimensions of the ICF framework as they manifest in the narratives describing the lived experiences of people who suffer from LBP, while valuing and respecting the uniqueness of the person.

Appendix 1. Focus group interview guide (abridged version).

In what part of your body is the pain localized?

Probe: location of primary and secondary pain and discomfortIn what part of your body do you feel the pain is coming from?

Probe: Joints, muscles, bonesWhat sorts of physical problems have you noticed about yourself while living with LBP?

Probes: strength and endurance; movements and postureWhat sorts of emotional or mental responses have you noticed about yourself while living with LBP?

Probes: ability to concentrate, if easily distracted, energy levels, ability to fall and stay asleepIf you think about your daily life, what difficulties do you encounter living with LBP?

Probe: impact on day-to-day activities, carrying on with usual work or household activitiesTell us about some of the social activities you are involved in.

Probes: : limitations, barriers, impact on others (e.g. friends, family, colleagues); frequency socializingThink about yourself, your life situation, gender, who you are – how does it affect the way you function?

Probe: experiences with low back painThinking about your environment, e.g. home, working conditions and social settings, what do you think are some things that enable you to function better?

Probe: developed habits or use of devicesHow well do you think society understands you? Would you say people are supportive in helping you manage from day-to-day? How?

Probe: attitudes and assistance of those around youWhat services and/or resources in the community have you used and found helpful?

Probe: system or people assistanceReflecting or thinking about your surroundings, e.g. home, working conditions and social settings, is there anything that limits your ability to adequately function? What limits you and how?

Probe: challenges and limitations through the dayDescribe any services or resources which you find difficult to use or implement into your everyday life? Probe: difficulties accessing or using resources or services

Funding:

Norwegian Research Foundation “Et liv i bevegelse” (ELIB), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Canada Research Chair Program.

Competing interests

The authors have no disclaimers or competing interests to report in the preparation of this manuscript.

References:

Cote P, Cassidy JD, Carroll L.

The Saskatchewan Health and Back Pain Survey.

The Prevalence of Neck Pain and Related Disability in Saskatchewan Adults

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998 (Aug 1); 23 (15): 1689–1698Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators (2015)

Global, Regional, and National Incidence, Prevalence, and Years Lived with Disability for 301 Acute

and Chronic Diseases and Injuries in 188 Countries, 1990-2013: A Systematic Analysis

for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013

Lancet. 2015 (Aug 22); 386 (9995): 743–800Mutubuki EN, Luitjens MA, Maas ET, Huygen FJPM, Ostelo RWJG, van Tulder MW.

Predictive factors of high societal costs among chronic low back pain patients.

Eur J Pain. 2019; 24(2): 325-337.Van Tulder M, Koes B, Bombardier C.

Low back pain.

Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2002; 16(5): 761-775.Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, Louw Q, Ferreira ML, Genevay S, Hoy D, Karppinen J et al.

What Low Back Pain Is and Why We Need to Pay Attention

Lancet. 2018 (Jun 9); 391 (10137): 2356–2367

This is the second of 4 articles in the remarkable Lancet Series on Low Back PainWong JJ, Cote P, Sutton DA, et al.

Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Noninvasive Management of Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review

by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration

European J Pain 2017 (Feb); 21 (2): 201–216Glenton C.

Chronic back pain sufferers--striving for the sick role.

Soc Sci Med. 2003; 57(11):2243-2252.Crowe M, Whitehead L, Gagan M J, Baxter GD, Pankhurst A, Valledor V.

Listening to the body and talking to myself – the impact of chronic lower back pain: a qualitative study.

Int J Nurs Stud. 2009; 47(5): 586-592.Dima A, Lewith GT, Little P, Moss-Morris R, Foster NE, Bishop FL

Identifying patients’ beliefs about treatments for chronic low back pain in primary care:

a focus group study.

Br J Gen Pract. 2013; 63(612): e490-e498.Holloway I, Sofaer-Bennett B, Walker J.

The stigmatisation of people with chronic back pain.

Disabil Rehabil. 2007; 29(18): 1456-1464.Darlow B1, Dean S, Perry M, Mathieson F, Baxter GD, Dowell A.

Easy to harm, hard to heal: patient views about the back.

Spine 2015: 40(11): 842-850.Froud R, Patterson S, Eldridge S, Seale C, Pincus T, Rajendran D, Underwood M.

A systematic review and meta-synthesis of the impact of low back pain on people’s lives.

BMC Musculoskel Dis. 2014; 15: 50.Smith JA, Osborn M.

Pain as an assault on the self: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the psychological impact

of chronic benign low back pain.

Psychol Health. 2007; 22(5): 517-534.Nolet PS, Kristman VL, Cote P, et al.

Is Low Back Pain Associated With Worse Health-related Quality of Life 6 Months Later?

European Spine Journal 2015 (Mar); 24 (3): 458–466Walker J, Sofaer B, Holloway I.

The experience of chronic back pain: Accounts of loss in those seeking help from pain clinics.

Eur J Pain. 2006; 10(3): 199-207.Snelgrove S, Edwards S, Liossi C.

A longitudinal study of patients’ experiences of chronic low back pain using interpretative phenomenological

analysis: changes and consistencies.

Psychol Health. 2013; 28(2): 121-138.World Health Organization.

International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF.

Geneva: WHO; 2001.Madans JH, Loeb ME, Altman BM.

Measuring disability and monitoring the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities:

the work of the Washington Group on Disability Statistics.

BMC Pub Health. 2011; 11 Suppl 4: S4.Cieza A, Fayed N, Bickenbach J,et al.

Refinements of the ICF Linking Rules to strengthen their potential for establishing comparability

of health information.

Disabil Rehabil. 2016; Mar 17: 1-10.Morgan D L. Focus Groups.

In L. M. Given (Ed.) The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods.

SAGE Publications, Inc., 2008: 353-355.WHO Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) [Internet].

World Health Organization. World Health Organization; 2019 [cited Jan 30 2020]. Available from:

https://www.who.int/classifications/icf/more_whodas/en/World Health Organization (WHO) (2002).

Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health: ICF -

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva: WHO.

http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/Geyh S, Schwegler U, Peter C, Müller R.

Representing and organizing information to describe the lived experience of health from a personal

factors perspective in the light of the International Classification of Function,

Disability and Health (ICF): a discussion paper.

Dis Rehabil. 2019: 41(14): 1727-1738.Wawrzyniak KM, Finkelman M, Schatman ME, Kulich RJ, Weed VF, Myrta E.

The World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule-2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) in a chronic pain

population being considered for chronic opioid therapy.

J Pain Res. 2019:12 1855–1862.Von Korff M, Crane PK, Alonso J, Vilagut G, Angermeyer MC, Bruffaerts R, Ormel J.

Modified WHODAS-II provides valid measure of global disability but filter items increased skewness.

J Clin Epidemiol. 2008; 61(11): 1132-1143.Silva C, Coleta I, Silva AG, Amaro A, Alvarelhão J, Queirós A, Rocha N.

Adaptation and validation of WHODAS 2.0 in patients with musculoskeletal pain.

Revista De Saúde Pública. 2013; 47(4): 752.Marx BP, Wolf EJ, Cornette MM, Schnurr PP, Rosen MI, Friedman MJ.

Using the WHODAS 2.0 to assess functioning among veterans seeking compensation for posttraumatic stress disorder.

Psychiatric Serv. 2015; 66: 1312-1317.Snelgrove S, Liossi C.

Living with chronic low back pain: a metasynthesis of qualitative research.

Chron Illness. 2013: 9(4): 283-301.Ashby S, Fitzgerald M, & Raine S.

The impact of chronic low back pain on leisure participation: implications for occupational therapy.

Br J Occup Ther. 2012; 75(11): 503-508.Naughton F, Ashworth P, Skevington SM.

Does sleep quality predict pain-related disability in chronic pain patients?

The mediating roles of depression and pain severity.

Pain. 2007;127(3): 243–252.Fu Y, Mcnichol E, Marczewski K, Closs SJ.

Patient-professional partnerships and chronic back pain selfmanagement:

a qualitative systematic review and synthesis.

Health SocCare Commun. 2015;24(3):247–259.Hopayian K, Notley C.

A systematic review of low back pain and sciatica patients expectations and experiences of health care.

Spine J. 2014;14(8):1769–1780.Matthews CK.

To tell or not to tell: The management of privacy boundaries by the invisibly disabled.

In: Annual meeting of the Western States Communication Association,

San Jose, CA., 1994.Pape TL, Kim J, Weiner B.

The shaping of individual meanings assigned to assistive technology:

a review of personal factors.

Disabil Rehabil. 2002; 24 (1/2/3): 5-20.Shinohara K, Wobbrock J.

In the shadow of misperception: Assistive technology use and social interactions.

Paper presented at the CHI 2011, Vancouver BC, Canada May 7-12, 2011: 705-714.Corbett M, Foster NE, Ong BN.

Living with low back pain--Stories of hope and despair.

Soc Sci Med. 2007; 65(8): 1584.Walker J, Sofaer B, Holloway I.

The experience of chronic back pain: Accounts of loss in those seeking help from pain clinics.

Eur J Pain. 2006; 10(3): 199-207.Jette AM, Haley SM, Kooyoomjian JT.

Are the ICF activity and participation dimensions distinct?

J Rehabil Med. 2003; 35(3): 145-149.Badley EM.

Enhancing the conceptual clarity of the activity and participation components of the international

classification of functioning, disability, and health.

Soc Sci Med. 2008; 66(11): 2335-2345.Resnik L, Plow MA.

Measuring participation as defined by the international classification of functioning,

disability and health: an evaluation of existing measures.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009; 90(5): 856-866.Okunribido OO, Shimbles SJ, Magnusson M, Pope M.

City bus driving and low back pain: a study of the exposures to posture demands, manual materials

handling and whole-body vibration.

Applied Ergon. 2007; 38(1): 29-38.Arnow BA, Blasey CM, Constantino MJ, Robinson R, Hunkeler E, Lee J.

Catastrophizing, depression and pain-related disability.

Gen Hosp Psych. 2011; 33(2): 150-156.Geyh S, Peter C, Müller R, Bickenbach JE, Kostanjsek N, Ustun, BT.

The personal factors of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health

in the literature – a systematic review and content analysis.

Disabil Rehabil. 2011; 33(13-14): 1089-1102.Kostanjsek N.

Use of The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) as a conceptual

framework and common language for disability statistics and health information systems [Internet].

BMC public health. BioMed Central; 2011 [cited Jan 30 2020].Carr JL, Moffett JAK.

Review Paper: The impact of social deprivation on chronic back pain outcomes.

Chron Illness. 2005;1(2):121–129.Campbell P, Jordan KP, Dunn KM.

The role of relationship quality and perceived partner responses with pain and disability

in those with back pain.

Pain Med. 2012;13(2):204–214.

Return LOW BACK PAIN

Return to BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL MODEL

Since 5-02-2019

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |