Opportunities to Integrate Prevention Into the Chiropractic

Clinical Encounter: A Practice-based Research Project By

the Integrated Chiropractic Outcomes Network (ICON)This section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Topics in Integrative Health Care 2011 (Oct 7): 2 (3) ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Cheryl Hawk, DC, PhD, CHES, Marion Willard Evans, Jr., DC, PhD, MCHES, CWP

Ronald L. Rupert, DC, MS, Harrison Ndetan, MSc, MPH, DrPH

Purpose: to collect exploratory data on the characteristics of chiropractic practices participating in a practice-based research network (PBRN), particularly with respect to important health promotion and disease prevention activities, to lay the groundwork for future longitudinal studies.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional descriptive study conducted by the methods of practice-based research in the offices of participating U.S. chiropractors. Data were collected by self-report from practitioners and from all patients presenting for treatment in the participating offices for one week in March 2011.

Results: Data were collected on 1891 patients of 38 Doctors of Chiropractic (DCs) in 30 practices in 17 U.S. states. Forty-seven percent of DCs reported that they routinely gave advice on diet; 26% on weight management; and 21% on tobacco use. Of the 1891 patients, 24.9% were presenting for wellness/maintenance care only. Forty percent of patients’ health concern’s duration was > 1 year. The mean number of annual visits reported by patients was 14. Of the 12.4% of patients who reported using tobacco currently, 29.1% reported that their practitioner discussed quitting with them. About 40% of patients reported being overweight; 19.5% reported that they received information from their DC on weight management. Only 9.2% of patients reported being obese; 31.6% reported receiving information on weight management from their DC.

Conclusion: Chiropractic patients in this sample presented with risk factors amenable to physician counseling. Their DCs reported routinely providing advice on some risk factors, and a substantial proportion of patients with risk factors reported receiving advice from their DC. Chiropractic practices, in which patients with chronic pain have frequent follow-up visits, present an opportunity to advise patients on health risks, which could contribute to improved health outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

The U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) defines a practice-based research network (PBRN) as “a group of ambulatory practices devoted principally to the primary care of patients, and affiliated in their mission to investigate questions related to community-based practice and to improve the quality of primary care. This definition includes a sense of ongoing commitment to network activities and an organizational structure that transcends a single research project.” [1]

PBRNs address research questions that require a real-world setting to be answered. Ambulatory care settings, linked through the academic institution operating the PBRN, are well-suited to address the type of research questions related to the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine’s Strategic Objective 3: “to increase understanding of real-world patterns and outcomes of CAM use and its integration into health care and health promotion.” [2]

Chiropractic research, to date, has focused more on pain and symptom management than on prevention and health promotion, even though chiropractic has traditionally considered itself to be prevention-oriented. [3] However, in a time when lifestyle factors have become the leading actual causes of death, [4] research into the role of chiropractic in disease prevention and health promotion must become a priority. At this time, such evidence is scarce. Some studies have shown that wellness care accounts for a significant proportion of chiropractic patient visits, [5–7] and others suggest that patients receiving chiropractic care appear to be healthier than patients who do not; [6, 8] however, a cause-and-effect relationship between wellness care and improved long-term health outcomes has yet to be clearly demonstrated.

The Integrated Chiropractic Outcomes Network (ICON)

PBRNs have been used in other health professions as well as chiropractic for many years to investigate ways to improve clinical practice, including the delivery of health promotion and prevention services. [3–9] The Integrated Chiropractic Outcomes Network (ICON) is a new PBRN representing an interinstitutional collaboration among three chiropractic colleges. ICON is intended to be an “engine” that can drive projects that require a real-world ambulatory care setting in order to answer specific research questions. ICON’s mission is to conduct collaborative research through a partnership between researchers and practitioners with the ultimate goal of enhancing the health of the public and contributing to the scientific evidence base related to health promotion and disease prevention. Its first study was designed to be a “snapshot” of the participating practices, particularly with respect to important health promotion and disease prevention activities, to lay the groundwork for future longitudinal studies.

METHODS

Specific Aims

This was a cross-sectional descriptive study. Its specific aims were to:

describe practice characteristics, including self-reported health promotion and disease prevention services, of participating practitioners.

describe baseline demographics, chief complaints, specific self-reported health habits and risk factors of patients of participating practitioners.

assess patients’ prevention and health-promotion related experiences and expectations of their providers in the participating practices.

Protection of Human Participants

The project was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each collaborating institution prior to enrollment of any doctors or patients. Participation agreements, which included the standard elements of informed consent, including the program’s methods for protecting participating doctors’ and patients’ confidentiality and data integrity, were required to be signed by both the participating chiropractor and the ICON program director (principal investigator) before any data were collected. Since the patient data were anonymous, the IRB approved a modification of the informed consent process, in which the following statement was included at the top of the patient data collection form: “This survey collects information about patients’ health and their experience in this office. Taking part or not taking part will not affect your relationship with your practitioner. All answers are anonymous and will be reported in group form only. Completing this survey implies your consent to participate.” Methods developed for addressing HIPAA regulations in PBRNs were followed. [10]

Study Eligibility

Doctors of Chiropractic (DC) were eligible to become ICON members if they were in current chiropractic practice in the United States and completed the participation agreement and the practice characteristics forms. Only DCs who were ICON members participated in the study. Patients of all ages, both new and established, who presented for care to the participating offices during the designated one-week study period were eligible for inclusion. Only patients (or the parent or guardian of children too young to assent) who declined to participate were excluded.

DATA COLLECTION

Types of Data Collection

1) Data Collection on Practitioner and Practice Characteristics. All participating practitioners completed a one-time questionnaire after they agreed to participate and prior to the enrollment of any patients.

2) Patient Self-Report Data Collection in Participating Offices. All patients seeking care during the data collection week were to be invited by office staff to complete the one-page form prior to seeing the doctor. For children, their parent or accompanying adult completed the form.

Study Interval

One week in March 2011 (Monday through Saturday) was designated as the data collection week.

Data Collection Instruments

Patient Self-Report Forms. A one-page form collected information on patient demographics, chief complaint, risk factors (specifically, overweight and obesity; tobacco use; hypertension and diabetes) and the patient’s experience in receiving health promotion information in the participating practice. Most questions were closed-ended. The question on chief complaint, which has been used in a previous study, [11] gave options of1) “no problem today (check-up, spinal health or wellness/maintenance care only);”

2) “pain of any type;”

3) “other concern (not pain): please describe.”The “other concern” option was recorded verbatim by the data clerks and coded by the principal investigator.

Doctor Report Forms on Practice and Practitioner Characteristics. One doctor in each practice completed a one-page form on characteristics of the entire practice (location, population of community, referral patterns, etc.). A two-page form including both closed-ended and open-ended questions was completed by each doctor once. It collected information on demographics; estimation of weekly patient volume; type of spinal adjustment technique(s) and other routine services and procedures with emphasis on clinical preventive services recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. [12] All the questions except those about clinical preventive services had been used in previous studies. [11, 13, 14] The section about preventive services provided lists of the selected topics, requiring the doctors to mark how frequently they used each service with patients. The question on participants’ scope referred to the scope of practice scale defined by McDonald et al, which is a 9–point scale using the following defintions: [15]

Marking 1, 2 or 3 on the scale indicated broad scope, which includes a wide array of manual and other procedures to diagnose and treat broad array of conditions.

Marking 4, 5, or 6 indicated middle scope , which combines subluxation adjusting with other conservative treatment and diagnostic procedures.

Marking 7, 8, or 9 indicated focused scope, which includes detection and adjustment of vertebral subluxations to restore normal nerve function.

TRAINING AND RETENTION OF PARTICIPATING PRACTICES

Training of Participating Doctors and their Staff

To optimize compliance of the participating practices with study protocols, the program coordinator (PC) maintained close communication with the doctors and their office staff. The PC provided each participating office with user-friendly, succinct instructional materials. She instructed each doctor and the office staff he or she designated as the on-site study manager in the details of the study protocol, reinforced by the printed materials.

Retention

In order to maintain enthusiasm and buy-in for the project and for future projects, the PC maintained continued close contact with both doctors and their staff by writing and answering letters, phone calls, and e-mails. Previous studies emphasize the importance of on-site office staff involvement. [11, 13, 14, 16, 17] To facilitate this, we used several methods to maintain participants’ enthusiasm and compliance:

Summary reports. At the close of the data collection period, each participating practice was sent a summary of the descriptive statistics for this period.

Acknowledgment. Participating practitioners will be acknowledged by name in the “Acknowledgment” section of all journal articles resulting from the study. Practitioners and their staff are also sent certificates of appreciation.

DATA MANAGEMENT AND ANALYSIS

Data Management

The project team developed a data coordinating system for implementation using methods developed by the investigators for other clinical and PBRN projects. [11, 13, 14] The data were stored in secured relational database tables using Microsoft Excel. The system allowed both tracking of practitioner contacts and management of key-entered data. The program coordinator used the practitioner contact database to prepare mailings and to track training activities, participant agreement forms, data collection form delivery and return. Only the program coordinator had access to this database.

The data were handled in a standardized manner. The data manager prepared data for key entry. Data went through a double entry verification process, which was implemented by means of a program in SPSS (practitioner dataset) or SAS (patient dataset). The verified datasets were imported to SPSS for analysis. Hard-copy forms were subsequently stored in a secure, fire-resistant data storage cabinet.

Quality Assurance

Procedures used successfully in previous studies for ensuring as complete and accurate data collection and management as possible were followed. [1–5] Participating practices’ office staff were provided with a form to record numbers of patients who declined to participate. The program coordinator communicated regularly with doctors and their staff, as described above, to ensure the timely completion of required forms.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed using SPSS (v.16.0). Categorical variables were reported as percentages of the total sample. Mean, median, and range were reported for continuous variables.

RESULTS

Practice Characteristics

Thirty practices with a total of 38 DCs participated in the project. Nine (30%) were solo practices and 21 (70%) had multiple practitioners. For those with more than 1 practitioner, the median was 2 and maximum 6. All 21 group practices included more than 1 DC; 16 included a massage therapist; 4 a physical therapist, 1 an acupuncturist. The mean estimated total number of patient visits per week to the practices was 139 (median, 110; minimum, 6; maximum, 400). Most (53%) practices were located in suburban areas, 23% in small towns, 20% urban and 3% rural.

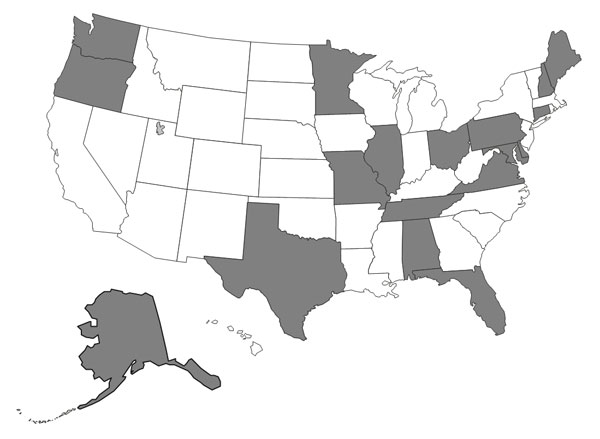

Figure 1

Table 1

Table 2

Table 3

Table 4

Table 5A

Table 5B

Table 6

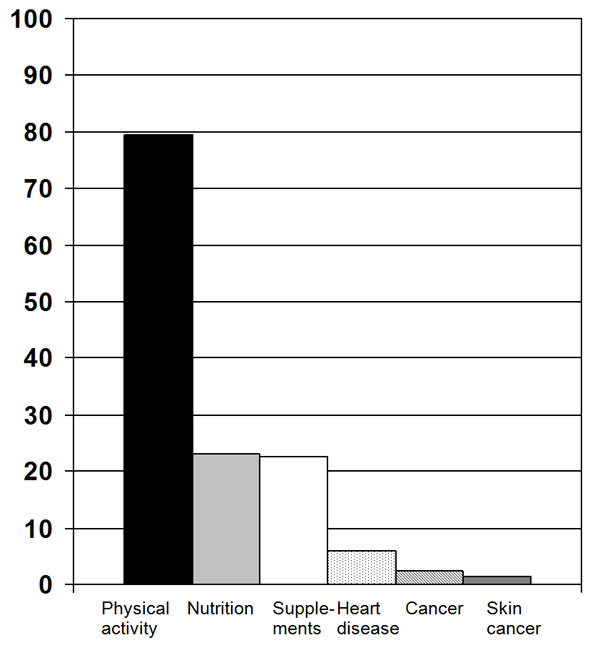

Figure 2 Part A

Figure 2 Part B As shown in Figure 1, practices were located in 17 states (AK, AL, DE, FL, IL, MD, ME, MN, MO, NH, OH, OR, PA, TN, TX, VA, WA).

Concerning X-ray facilities, 70% had on-site facilities; 27% had a standing arrangement with a local radiology clinic; and 3% had a standing arrangement with a local medical physician. Eighty percent had the capacity to order laboratory tests.

Nearly all (97%) provide educational materials in the office for patients, including brochures (87%), computer or video format (40%) as well as on their practice website (60%). Most of the practices create these materials in-house (73%) or from chiropractic sources (80%); 13% obtain them from government agencies.

Practitioner Characteristics

Of the 38 DCs, 74% were men and 26% women. They were graduates of 14 chiropractic colleges, 12 in the U.S., 1 in Canada and 1 in England. They had been in practice for a mean of 16 years (median 18, range 1–35). The mean estimated number of patient visits per week for each practitioner was 103 (median 110, range 6–285) and the mean estimated number of individual patients seen per week was 65 (median 45, range 2–285).

In terms of scope of practice, 84% (24) described themselves as broad scope, 29% (11) middle scope, and 8% (3) focused scope. Thirty-five (92%) used more than one type of manipulative/adjustive technique. All but one DC used one manipulative technique with over 50% of patients; this primary technique was usually traditional manual (66%), followed by table-assisted (18%), instrument-assisted (8%) and manual low-force (3%). Practitioners also used instrument-assisted (71%), table-assisted (71%), traditional manual (24%) and manual low-force (45%) procedures, in additional to their primary technique.

Preventive Services. Ninety-five percent of the 38 practitioners reported that they recommend preventive care to their patients for the purpose of preventing recurrences and exacerbations of a chronic condition, while 71% reported that they recommend preventive care to asymptomatic patients to promote optimal function (wellness care).

Table 2 summarizes the prevention-related topics on which the 38 DCs report obtaining information from new patients. The topics most frequently addressed (with > 80% of patients) were medication use, current and former tobacco use and physical activity.

Table 3 summarizes the topics for which the 38 DCs provide advice and information to at-risk patients. Diet, weight management and alcohol misuse were the topics most frequently addressed; 47% of DCs reported that they routinely gave advice on diet; 26% on weight management, 24% on alcohol and 21% on tobacco use.

Table 4 summarizes the frequency with which the 38 DCs either perform or refer to other practitioners for screening tests for patients in the appropriate risk categories. Blood pressure, aortic aneurysm and body mass index were the screening procedures reported as being most often used.

Patient Characteristics

A total of 1891 patients completed the questionnaire; the mean number of questionnaires per practitioner was 50 (median 41; range 2–231). A total of 205 patients declined, among the 36 practitioners who reported this number; the mean was 6 (median 2, 0–79), with 13 practitioners reporting no declines, 6 reporting 1, and 1 reporting 79.

Of the 1891 patients, 94.3% (1783) had received care in the participating office prior to the current visit. Of these established patients, 34.6% (613) had been a patient at the office for less than 1 year and 65.6% (1170) for more than 1 year, with a mean of 7.2 years (median 5.0, range 1–46). Of the patients who had been visiting the practice for at least 1 year, the mean reported number of visits was 14 (median 11, range 0–150).

Table 5 summarizes the patients’ demographics and main reasons for seeking care on the day of their visit. Patients had primarily pain-related concerns (72.5%) and 24.9% had no problem today but were presenting for check-up, spinal health or wellness/maintenance care only. The duration of their health concern was more than 1 year for 40.2%, with 10.5% reporting that they had had the concern less than 1 week.

Table 6 summarizes the self-reported presence of specific risk factors, along with the patients’ report of receiving advice or information by their DC. Only 12.4% reported using tobacco currently. Of these, 29.1% reported that their practitioner discussed quitting with them, 13.7% that he/she gave them information on how to quit, and 12.0% that there was follow-up on a different visit. About 40% reported being overweight, with 19.5% of those saying they received information from their DC on weight management. Only 9.2% reported being obese, and of those, 31.6% reported receiving information on weight management from their DC.

As shown in Figure 2, advice on physical activity was by far the most commonly reported topic which patients reported their DC providing (79%), followed by advice on diet and nutrition (23%) and nutritional supplements (23%).

DISCUSSION

This study had several limitations. First, as with any practice-based research study, it was subject to volunteer bias, both at the level of the practitioner and the patient. With respect to the possibility of practitioner volunteer bias, it seems likely that our participants tended to be broader in scope than DCs in general. The 2004 survey by McDonald et al, [15] in which this particular scope of practice definition was first used, indicated that about one-third of U.S. DCs consider themselves “broad scope,” compared to 84% of our participants, although it is possible that this perspective may have changed since 2004. On the other hand, our participants’ demographics and practice characteristics, including number of patients per week, are very similar to those described in the 2010 Practice Analysis of Chiropractic, the largest survey of the chiropractic profession. [18] At the patient level, it appears that the practitioners’ estimate of number of patients per week was quite close to the actual number of forms submitted (median 45 vs 41, respectively). Furthermore, the median number of patients who were reported to have declined, per practitioner, was 2, which would suggest that any bias in patient selection was likely minimal. Patient demographics were comparable to those reported in the Practice Analysis of Chiropractic, as well. [18]

Another important limitation was the use of self-report data, particularly concerning health risks. Patients may have not known or not been willing to disclose the presence of overweight, obesity, hypertension or diabetes, and may not have been willing to disclose their tobacco use. Patient-reported overweight was 40%, similar to the current national average of 34%, but self-reported obesity, at 9%, was far lower than the national average of 32%. [19] In a 2000 practice-based research study of 805 chiropractic patients aged 55 and older, their BMI was calculated from height and weight measured by their DCs, and showed a mean proportion of overweight of 39% and obesity of 21%. [14] In that study, 12.7% reported tobacco use, compared to 12.4% in this sample; it is possible that chiropractic patients tend to use tobacco less than the national average of 21%. [20]

Opportunities for Prevention

The patient sample exhibited common risk factors amenable to counseling—particularly overweight and tobacco use—indicating an opportunity for intervention, particularly considering that the median number of visits per year was 11, thus providing multiple occasions for reinforcement of health messages. Furthermore, 65.6% of patients had been patients at the participating office for more than one year—the mean was, in fact, 7.2 years. This indicates considerable continuity of care, an established relationship with their DC, and frequent opportunities for the delivery and follow-up of health messages.

About 29% of those who reported tobacco use said that their DC had talked to them about quitting. Although there are no directly comparable measures for medical physicians, a 2007 report stated that primary care medical physicians gave advice on quitting at 20% of patient visits, although it is possible that rates have changed since that time. [21] Just under 20% of overweight patients reported the doctor gave them advice on weight management, and this increased to about 32% in those who stated they were obese. Comparably, a 2000 study indicated that 32.4% of obese patients without comorbidities (47.3% with comorbidities) received weight management advice from their medical physician. [22]

Manson and colleagues have called on all health care providers to counsel those who are overweight and obese. [23] Fiore and other researchers for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have outlined a program available to all health care providers and encourage every provider to offer tobacco cessation advice at each opportunity. [24] With advice related to increasing physical activity and other healthy behaviors, these clearly represent opportunities for clinicians to provide information, resources and cues to action for patients in the areas of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention. In a recent analysis of respondents to the 2007 National Health Interview Survey who had sought spinal manipulation in the past year, 46% of patients aged 50 and older reported use of such services for general wellness and disease prevention. [25] About 25% of patients in our sample reported that their current visit was for a “check-up, spinal health or wellness/maintenance care only.” This presents an opportunity to advise patients in a non-acute care environment, which could contribute to improved health outcomes. Further investigation as to how to assist doctors in gaining self-efficacy in this capacity are warranted.

CONCLUSION

Chiropractic patients in this sample presented with risk factors amenable to physician counseling. Their DCs reported routinely providing advice on some risk factors, and a substantial proportion of patients with risk factors reported receiving advice from their DC. Chiropractic practices, in which patients with chronic pain have frequent follow-up visits, present an opportunity to advise patients on health risks, which could contribute to improved health outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Michelle Anderson, Program Coordinator at Logan College of Chiropractic, Maria Dominguez, Research Coordinator at Parker University and Dr. Patricia Brandon, Practice-Based Research Project Specialist at Parker University for their essential roles in conducting this project. We also thank the Doctors of Chiropractic who participated in the project for generously contributing their time and that of their office staff: Birger Baastrup, DC, CCSP; Richard Bechert, DC; Jon Blackwell, DC; Hans Bottesch, DC; Mary Brechtel, DC; Richard Bruns, DC; Deana Burd, DC; Brad Cole, DC, MS; Katharine Conable, DC; James Copeland, DC; Jennifer Davis, DC, CCEP; Mark Davis, DC; Mark Dehen, DC; Martin Donnelly, DC, CKTP; Ronald Farabaugh, DC; Simon Forster, DC, DABCO; Katanah Grossman, DC; Johanna Hoeller, DC, PS; Melanie Massare, DC; Christopher McClenney, DC; Brad McKechnie, DC; Julie McKechnie, DC; Karin Nosrati, DC; Frank M. Painter, DC; Jose Ramirez, DC; Case Ricks, DC; Bruce Rippee, DC, CCWP; Everett Scott, DC, CKTP; Maurice Smith, DC; Darek Stanfield, DC; Ricardo Tersigni, DC, CKTP; Jennifer Tinoosh, DC, MUAC; Steven Vollmer, DC; James Whedon, DC; Wayne White, DC; J. Todd Whitehead, DC; Jake Wyllie, DC, CCWP; James Wyllie, DC, DABCO, CCWP.

References:

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

AHRQ Practice-Based Research Networks (PBRNs).

Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2011.National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

Draft Strategic Plan. Bethesda, MD:

National Institutues of Health, 2010.Cifuentes M, Fernald DH, Green LA, et al.

Prescription for health: changing primary care practice to foster healthy behaviors.

Ann Fam Med 2005;3 Suppl 2:S4-11.Cohen DJ, Tallia AF, Crabtree BF, Young DM.

Implementing health behavior change in primary care:

lessons from prescription for health.

Ann Fam Med 2005;3 Suppl 2:S12-19.Hawk C, Long CR, Perillo M, Boulanger KT.

A survey of US chiropractors on clinical preventive services.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2004;27(5):287-298.Rupert RL:

A Survey of Practice Patterns and the Health Promotion and Prevention

Attitudes of US Chiropractors Maintenance Care: Part I

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2000 (Jan); 23 (1): 1–9Rupert RL, Manello D, Sandefur R:

Maintenance Care: Health Promotion Services Administered to US Chiropractic

Patients Aged 65 and Older, Part II

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2000 (Jan); 23 (1): 10–19Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Tallia AF, et al.

Delivery of clinical preventive services in family medicine offices.

Ann Fam Med 2005;3(5):430-435.Quintela J, Main DS, Pace WD, Staton EW, Black K.

LEAP--a brief intervention to improve activity and diet:

a report from CaReNet and HPRN.

Ann Fam Med 2005;3 Suppl 2:S52-54.Pace WD, Staton EW, Holcomb S.

Practice-based research network studies in the age of HIPAA.

Ann Fam Med 2005;3 Suppl 1:S38-45.Hawk C, Long CR, Boulanger KT.

Prevalence of Nonmusculoskeletal Complaints in Chiropractic Practice:

Report From a Practice-based Research Program

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2001; 24 (3) March: 157–169USPSTF.

Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. Washington, DC:

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), 2009.Hawk C, Long CR, Boulanger K.

Development of a practice-based research program.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1998;21(3):149-156.Hawk C, Long CR, Boulanger KT, Morschhauser E, Fuhr AW.

Chiropractic care for patients aged 55 years and older:

report from a practice-based research program.

J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48(5):534-545.McDonald W.P., Durkin K.F., Pfefer M.

How Chiropractors Think and Practice: The Survey of North American Chiropractors

Semin Integr Med 2004; 2: 92–98Hawk C, Baird R.

"Chiropractors Against Tobacco" pilot project: a practic-based research study.

J Am Chiropr Assoc 2005;42:8-15.Hawk C, Long C, Boulanger K.

Patient Satisfaction With the Chiropractic Clinical Encounter:

Report From a Practice-based Research Program

J Neuromusculoskeletal System 2001: 9 (4): 109–117Christensen M, Kollasch, M., Hyland, JK.

Practice Analysis of Chiropractic 2010

Greeley, CO: NBCE, 2010.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM.

Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004.

JAMA 2006 2006(295):1549-1555.CDC.

Tobacco use among adults--United States, 2005.

MMWR 2009;55(42):1145-1148.Thorndike AN, Regan S, Rigotti NA.

The treatment of smoking by US physicians during ambulatory visits: 1994 2003.

Am J Public Health 2007;97(10):1878-1883.Sciamanna CN, Tate DF, Lang W, Wing RR.

Who reports receiving advice to lose weight? Results from a multistate survey.

Arch Intern Med 14-28 2000;160(15):2334-2339.Manson JE, Skerrett PJ, Greenland P, VanItallie TB.

The escalating pandemics of obesity and sedentary lifestyle.

A call to action for clinicians.

Arch Intern Med 2004;164(3):249-258.Fiore M, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al.

Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update.

Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,

Public Health Service, 2008.Evans M, Ndetan H, Hawk C,.

Use of chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation by adults aged 50 and older:

an analysis of data from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey.

Top Integrative Health Care 2010;1(2)

Return to HEALTH PROMOTION & WELLNESS

Since 4-04-2016

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |