Despite the historic emphasis on treatment, prevention and health promotion

are receiving increased attention within the US health care system.1

These same health promotion tasks are considered by the National Academy of

Science and others as essential components of health services delivered by

primary care providers.2

Chiropractors are viewed by many as capable of and actively delivering

prevention and health promotion in addition to providing other primary care

services. 3–6

Prevention and health promotion activities administered by chiropractors are

in 2 general categories: those considered orthodox by the medical community (eg,

weight loss, exercise, smoking cessation) and those that are not (eg,

soft-tissue and osseous manual procedures and some dietary supplementation).

Previous research demonstrates that the orthodox activities used by primary care

medical providers are also used by chiropractors. 7–9

The nontraditional activities that rely on procedures such as spinal

manipulation have not been investigated. The concept that chiropractic care is

of value in maintaining health and preventing disease began with the work of

Palmer.10

This preventive treatment is traditionally referred to as maintenance care (MC).

MC has been defined as “a regimen designed to provide for the patient's

continued well-being or for maintaining the optimum state of health while

minimizing recurrences of the clinical status.”11

Many chiropractors believe that periodic patient visits permit the doctor to

identify joint dysfunction or subluxations and make corrections with spinal

manipulation or other manual procedures. These treatments are believed to

prevent disease of both neuromusculoskeletal and visceral origin.12

The purpose of this research is to explore the primary care prevention and

health promotion attitudes and practice patterns of chiropractors, in particular

the concept of MC, which has not been investigated in the United States. The

study uses a common instrument for health care research, the postal

questionnaire, and attempts to evaluate the therapeutic components believed

necessary for maintenance patient care, the rationale for its use, what

conditions respond most favorably, how frequently it is required, for which

patients it is recommended, and its economic impact.

Literature search methods

To identify information about chiropractic wellness and health promotion

activities and the concept of MC, comprehensive literature reviews were

conducted. This literature served the usual functions of assisting in creating

the contextual background and search for possible similar work and guided the

development of a survey instrument. Multiple online database searches including

all years available in all languages were conducted through both Medline and

Manual, Alternative, and Natural Index System (formerly Chirolars). Other

databases were excluded because they either did not index chiropractic

literature or the material indexed was redundant. Several search strategies were

developed with the following Medical Subject Headings: chiropractic, health

promotion, prevention, primary health care, and physician's practice patterns.

In addition, manual searches were conducted through the Chiropractic Research

Archives Collection and the Index to Chiropractic Literature as well as a

limited manual search and bibliographic tracking. The search identified only a

few studies related to the chiropractic physician's practice patterns directed

at health promotion and prevention activities. With the exception of the

development of a protocol and pilot study by Rupert et al,13

no other studies identified in the literature addressed the possible health

promotion role of manipulation/adjustment or other manual procedures used by

chiropractors. Although there has been some limited study of MC in Australia and

to an even lesser extent in Europe, there has been no similar study in the

United States. 12,14

Population sampling methods

This descriptive study was conducted with a weighted randomized sample of US

licensed chiropractors. A postal survey instrument was then mailed to the

selected doctors. Sampling was conducted with the database of the National

Directory of Chiropractic.15

The computerized version of the directory contains nearly 40,000 chiropractors

who are in active practice. Unlike the hard copy version that is published

annually, the computerized directory is updated continually. This database was

used to create printouts and mailing labels based on zip code. Zip codes are

created by the US Postal Service, with the first digit representing groups of

states and the second and third subdividing the regions into smaller geographic

areas. The final 2 digits are randomly assigned by the postal service and

represent small post offices in rural areas or postal zones in larger

cities.16

These final 2 numbers are randomly assigned by the postal service in such a

manner that selecting a number would ensure selection from all states, with

representation from rural areas and small and large cities. Selection with the

ending numbers of the zip code would also ensure a “weighting” of the sample

based on size of the state. The larger the state the more zip codes are used

ending in the same number. The ending numbers to be used for selection from the

computerized database were selected by a manual random drawing. This method

helped ensure that chiropractors from each state and from rural areas and large

cities were included in the mailing (but did not ensure their participation in

the study). Such assurances would not have been possible with a pure random

sample.

To obtain a sufficient sample size of US chiropractors for a confidence level

of 0.05, 390 completed and returned surveys were required. This sample size was

calculated in the same manner as described by Hawk and Dusio.7

The return rate of previous surveys of the profession has ranged from 20% to

60%. To ensure adequate response with an estimated response rate of

approximately 30%, 1500 surveys were prepared and mailed.

Questionnaire design

Postal questionnaires are a well-established method for research. The

chiropractic profession has a history of using these instruments for assessing

the health promotion activities of chiropractors. 7,12,13

No previous research questionnaire had been developed for investigating MC. The

instrument used for this study was created by the principal investigator with

the available literature on MC and discussions with practitioners. Revisions

were made after use in a pilot study. Questionnaires from the medical literature

were reviewed; key health promotion strategies, including exercise and smoking

cessation, were included to determine if chiropractors believed these to be

components of MC. To determine what chiropractors believed MC to be and to

prevent biasing that process, no definition of MC was provided with the survey.

Issues of questionnaire content, including length, manner of question design,

and order of questions, were created with established conventions. 17–19

The questionnaire developed for this research had a total of 40 questions. The

first 5 were demographic questions followed by 35 questions related to MC. Of

the 35 MC questions, 28 were developed with a 5-point ordinal Likert scale. With

each question related to MC, the doctor could select 1 of the following

responses: strongly agree, agree, undecided, disagree, or strongly disagree. The

final 7 questions required short fill-in answers. Twenty-three of the questions

related to 5 issues:

- What is the purpose of MC? (6 questions)

- Does the professional research adequately support MC? (2 questions)

- What body systems/conditions respond best to MC? (6 questions)

- What age groups of patients benefit most from MC? (4 questions)

- What therapeutic interventions constitute MC? (5 questions)

The remaining 12 questions related to usage, economic issues, and other

practice patterns.

Once the questionnaire content was established, it was administered to a

convenience sample of 24 chiropractors. As a result of this pilot, minor

modifications were made to some questions and the layout of the form. The

revised questionnaire was kept to a single page with fields that could be

checked in response to the Likert scale questions (Appendix 1). A special

printed message on the outside of the envelope stated “Please contribute five

minutes to professional research.” This notice was added to encourage a response

and also to advise that it was not the typical solicitation that floods

chiropractic offices. In addition to the questionnaire, a postage-paid envelope

was included. To make follow-up possible, a number was assigned to each of the

1500 doctors selected to receive a survey. This number was placed on a master

control list of the doctors and was kept by the principal investigator. The

number corresponding to each doctor was also placed on the top of the

questionnaire. Doctors were advised that their responses would be

confidential.

Data analysis

There were 40 data points for each of the 658 returned surveys. This created

a possible 25,920 data elements that were entered into a spreadsheet created by

the principal investigator with Statistical Product and Service Solutions 7.5

for Windows. The person commissioned to enter these data had a history of

accurate work and proofread questionnaire data after entry. In addition, the

principal investigator performed a random review of data entry to ensure

accuracy. SPSS was then used to create basic descriptive statistics, frequency

distribution, tables, and related analysis.

A total of 1500 surveys were mailed, and of those 701 (46.7%) were returned.

Of these, 43 (2.9%) were returned by the postal service as undeliverable, and

658 (44%) were returned with completed surveys. This provided an adequate rate

to be representative at a confidence level of <.05. At least 1 questionnaire

was returned for each state, and the states densely populated with chiropractors

provided the greatest response (California, 98; New York, 47; Florida, 42;

Texas, 37; Minnesota, 34; New Jersey, 28; Ohio, 27; Missouri, 26; Michigan, 25;

Illinois, 21; Colorado, 20). All other states had fewer than 20 surveys

returned. The demographics of the respondents included age, sex, and years in

practice (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of

surveyed chiropractors

| Sex (%) |

|

Years in

practice (mean 12.33) |

| Male |

83.4 |

1

to 5 |

22.4% |

| Female |

16.6 |

6

to 10 |

34.6% |

| Age (mean

44.0)(y) |

|

11

to 15 |

42.3% |

| 25

to 34 |

29.6% |

16

to 20 |

9.0% |

| 35

to 44 |

46.4% |

>20 |

14.1% |

| 45

to 54 |

13.2% |

New patients per

month |

|

| >55 |

10.8% |

Mean |

19.5 |

Of the respondents, 83.4% were men and 16.6% were women.

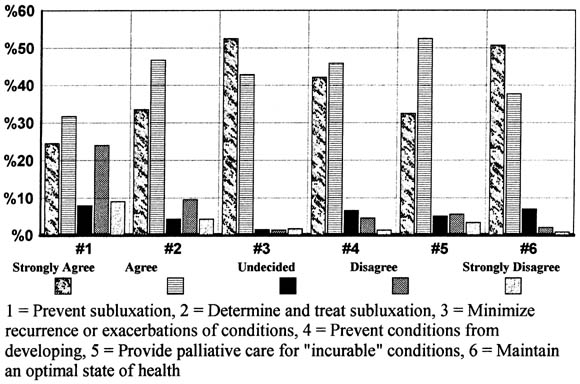

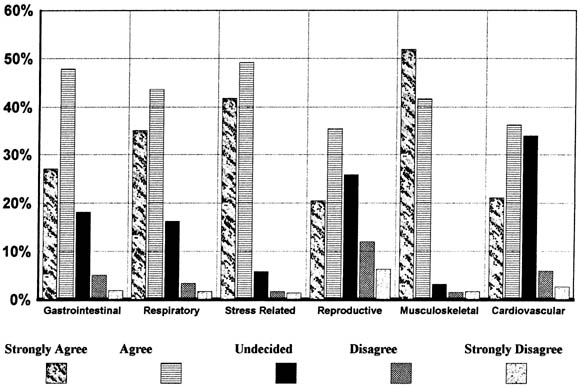

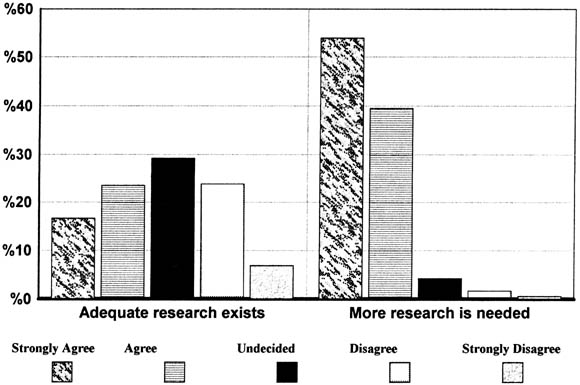

In general, there was a high level of agreement among respondents for most of

the questions. The 6 questions directed at understanding the reason for MC

resulted in agreement or strong agreement that its purpose was to minimize

recurrence or exacerbation (95.4%), maintain or optimize state of health

(88.3%), prevent conditions from developing (88.1%), provide palliative care for

“incurable” problems (84.9%), and determine and treat subluxation (80.2%). Only

56.2% agreed that the purpose of MC was to prevent subluxation. All but 2% of

responding chiropractors believed that MC provided benefit for 1 of 6 purposes

reflected in Fig 1.

|

Fig. 1. Purpose of MC. |

|

|

Click on Image to view full

size |

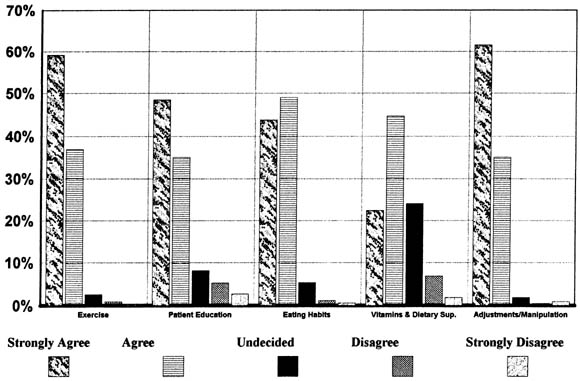

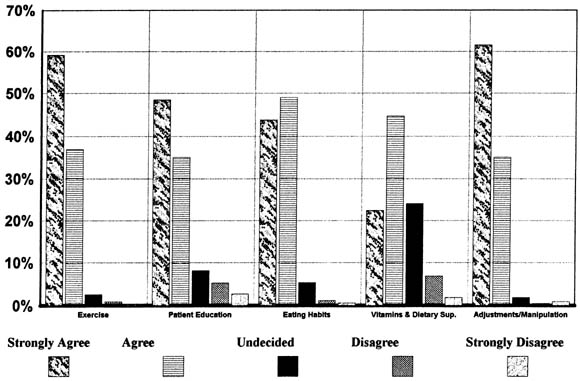

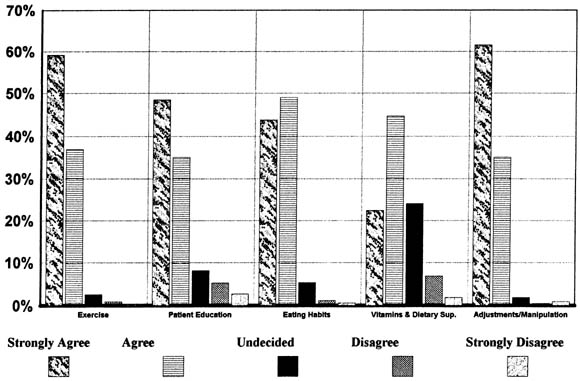

There was also agreement

about what the chiropractors saw as important therapeutic components to MC:

adjustments/manipulation (96.7%), exercise (96.1%), proper eating habits

(92.8%), patient education (eg, smoking, alcohol, drugs) (83.6%), and weaker

agreement on the use of vitamins and supplements (67.1%) (Fig 2).

|

Fig. 2. Therapeutic composition of MC. |

|

|

Click on Image to view full

size |

US chiropractors agreed

that MC was of value to all age groups, with the value increasing slightly with

an increase in a patient's age (Fig 3).

|

Fig. 3. Value of MC for patient subsets by age. |

|

|

Click on Image to view full

size |

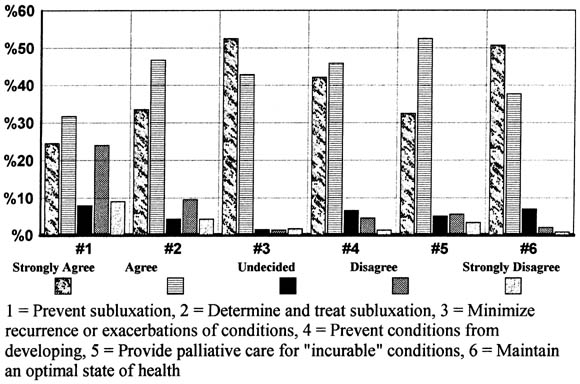

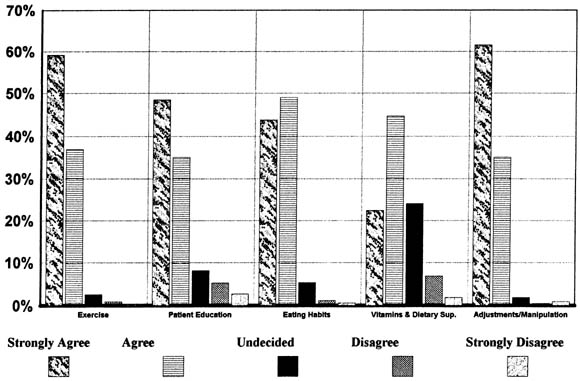

There was less agreement

on the issue of which body systems/conditions could be helped by MC:

musculoskeletal (93.6%), stress (91%), respiratory system (78.8%),

gastrointestinal system (74.9%), cardiovascular system (57.6%), and reproductive

system (56%) (Fig 4).

|

Fig. 4. Patients' response to MC condition/body

system. |

|

|

Click on Image to view full

size |

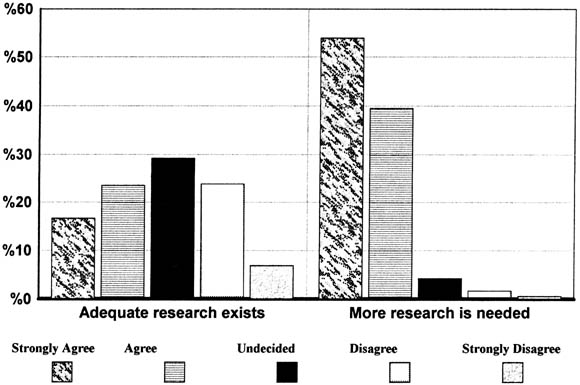

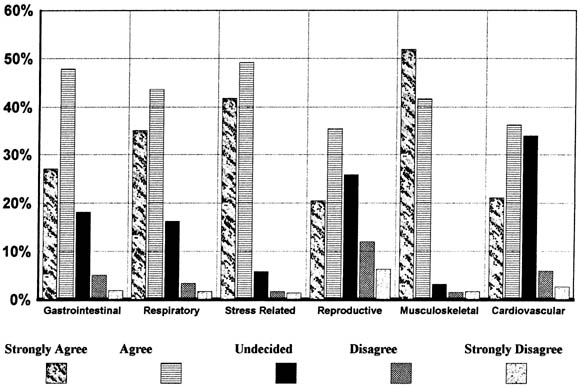

There were 2 questions that addressed research. Only 40.2% agreed that

adequate research existed to support the concept of MC and 93.4% agreed there

was a need for more research (Fig 5).

|

Fig. 5. Research status and MC. |

|

|

Click on Image to view full

size |

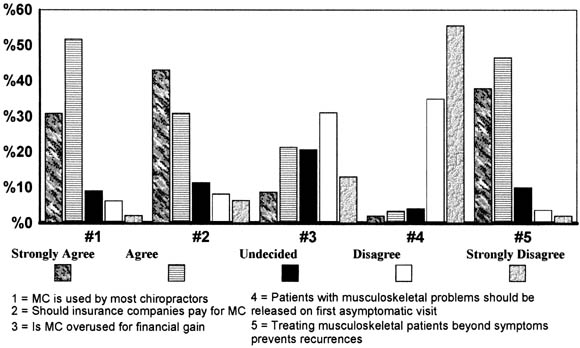

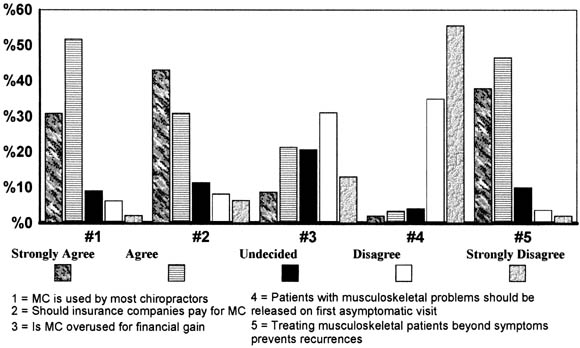

Fig 6 reflects the

responses of chiropractors about several issues: there was agreement that MC was

being performed by most chiropractors (81.9%), that it should be paid for by

insurance (72.3%), and that it helped prevent the return of musculoskeletal

conditions (84.5%).

|

Fig. 6. Miscellaneous questions. |

|

|

Click on Image to view full

size |

Based on the response to this survey, 78.7% of chiropractic patients are

recommended for MC and 34.4% of those elect to receive these services. These

patients average 14.4 visits annually for MC. Chiropractors estimated that 22.9%

of their total practice income was generated from MC services (Table 2).

Table 2. Doctors recommendations and reasons

for MC

|

Mean

(%) |

| Patients encouraged

to receive MC |

78.7 |

| Patients who

actually receive MC |

34.4 |

| MC patients treated

to prevent a return of specific conditions (eg, backache and

headache) |

55.2 |

| MC patients treated

to promote general well-being (not to prevent return of specific

conditions) |

36.0* |

| Average number of

visits required by MC patients each year |

14.4

visits |

| Income from MC

(%) |

22.9 |

* Estimated values do not total

100%. |

There was a significant inverse correlation (P < .05) between the

number of new patients per month and income from MC. The recommendation by

doctors for patients to receive MC was not related to practice income. The

belief of most chiropractors (98%) that MC provided some value in prevention or

health promotion was not correlated to practice income from MC services.

Postal surveys have inherent weaknesses but are a well-established form of

biomedical research. One of the specific weaknesses in this study involves

requesting chiropractors to provide the number of new patients per month, the

percentage of income derived from MC, and other data that are not based on

accurate counts and calculations but on estimates. In addition, the response

rate (44%), although disappointing, was relatively strong for a chiropractic

postal survey. Surveys within the profession rarely result in as much as a 50%

response rate; previous survey response rates related to chiropractic and

prevention have ranged from 22% to 65%. 7,12

A control number was assigned to each questionnaire to facilitate follow-up of

nonrespondents. However, this did not prove effective because many doctors who

did respond either obliterated, marked out, or actually tore off the number from

the form to ensure anonymity. With the accuracy of written follow-up

compromised, a selected follow-up was made by telephone. Eighty-five doctors for

whom there was no record of a completed questionnaire were called and asked (1)

if they completed the survey, (2) if they did not respond, why, and (3) if they

used MC in their practice. Doctors indicated that the most common reason for

nonparticipation was that they were too busy. The majority of nonrespondents

also reported that they used some form of MC in their practices.

A review of the demographics of chiropractors who completed and returned

questionnaires for this study did not vary significantly from other large

contemporary surveys, with the exception of sex. The annual survey conducted in

1995 by the American Chiropractic Association reflected a sex mix within the

profession of 88% men and 12% women.20

The response to this MC study and previous prevention-related research conducted

by Hawk and Dusio 7 both had a slightly higher percentage of female respondents

than the national American Chiropractic Association survey (83% male and 17%

female; 81% male and 19% female, respectively). Hawk and Dusio 7 indicated that

the larger number of female respondents may reflect a bias.7

However, a recent medical study suggests that female physicians may have a

greater interest in prevention activities than male physicians.21

This same phenomenon may in fact be operative within chiropractic and may

account for the greater participation of women in this prevention-related

survey. The average age of respondents in this study was 41 years compared with

an average age of 44 years in the 1995 American Chiropractic Association

survey.20

Prevalence of use

Previous work outside the United States suggests that the use of MC accounts

for a significant amount of services rendered by chiropractors. In England,

Breen22

noted that after management for conditions like low-back pain, “39% of patients

made further visits for maintenance treatment.” The Jamison12

study of Australian chiropractors found that 62% performed MC on up to one third

of their patients; 32% performed MC on 34% to 66% of their patients; and 6%

performed MC on 67% to 100% of their patients.23

This study attempted to address the same issues for chiropractors in the United

States. Chiropractors were asked to provide the percentage of their patient load

that received MC; the mean response was 34.4%. This suggests that a large

percentage of chiropractic care given around the world is directed at prevention

and health promotion. Shekelle24

reported that 42.1% of patient visits to chiropractors were for low-back

symptoms followed by 10.3% for neck/face symptoms. However, if as this study

suggests, 34.4% of patient visits are for the purpose of MC, then preventive

services may be the second most common reason for visits to a chiropractor. In

addition to this high percentage of patients receiving MC, a much higher number,

78.7% of US patients, receive the recommendation to continue with preventive MC.

This strong recommendation to receive preventive services suggests attitudes

that are similar to Australian chiropractors: 41% asserted that everybody would

benefit from such care, 38% believed that most would benefit, and 14% believed

that some patients would benefit.12

Despite the emphasis by the US Government on initiatives such as Healthy

People 2000,1

the medical community continues to face many obstacles to providing preventive

and health promotion services. 25–28

With the use of MC to the extent described in this study, the chiropractic

physician appears to place more emphasis on, derive more income from, and

perhaps commit more patient time to prevention and health promotion purposes

than many other health care professionals.

Another Australian study by Webb and Leboeuf14

found that there was a higher level of MC performed by doctors who had a lower

number of new patients per month. The current research confirmed similar

practice patterns (although number of MC visits was not ascertained) with a

statistically significant inverse relation and correlation (P < .05)

between the number of new patients per month and the practice income generated

from MC.

Economics of MC

In conjunction with the high percentage of patients who have been recommended

for MC and the nearly half that comply, there also is a relatively high

financial impact with an average 22.9% of all chiropractic income in the United

States generated from these services. Based on an annual gross income of

$225,783,20

MC accounts for an average annual income of $51,930 per practice. When the 22.9%

is viewed in the context of the total revenues of all chiropractors,29

this would equate to $48 million in MC services delivered to US citizens during

1994.

It was not possible to be more specific about how patients paid for MC

because of the necessity for reasonable brevity of professional surveys. Because

most health insurance policies will not reimburse policyholders for health

promotion services, future research should explore the methods of payment for

MC.

A few authors have stated or implied that there are serious ethical issues

with maintenance programs and that there is an inappropriate financial motive

for what is termed “spurious” services. 22,30

Homola30

states that “It is unfair to patients to allow them to believe that they must

have regular spinal adjustments in order to stay healthy.” Two findings from

this survey suggest appropriate financial motive to MC services. First, the

majority of the respondents (98%) agree that MC is of value for prevention and

promoting the health of their patients. Twelve respondents, representing only

1.9% of the responding population, indicated that they never recommended MC.

This consensus about the value of MC is remarkable considering the historical

disagreement within the profession about so many other issues. In addition to

the 98.1% of chiropractors recommending MC to their patients, 98% also agreed

with at least 1 of the 6 questions describing the possible health benefits of

MC. Chiropractors believe in the value of MC (98%) and therefore 98% recommend

its use to their patients. Recommending the use of a procedure without belief in

its value would suggest possible financial or other inappropriate motives, but

this is not the case with MC. Secondly, 70.5% of chiropractors responded that

they did not agree that MC was used for financial gain. Only 8.9% strongly

agreed that MC was overused. The belief that MC was overused was significantly

negatively correlated (P < .01), with both recommending MC to patients

and the belief in the value of MC. Thus doctors who did not believe there was

therapeutic value to MC (and did not or rarely recommended its use) were the

ones who believed MC might be overused for financial gain.

This survey did find a significant inverse relation (P < .05)

between the number of new patients per month and practice income from MC.

However, the recommendation to receive MC was not related to practice income.

There was also no correlation between income from MC and the doctors' belief

that MC was of value in promoting health. These facts suggest that despite the

number of new patients per month, chiropractors believe in the value of MC

regardless of whether or not they are actually deriving income from MC services

in their practices. It is possible that those chiropractors with lower patient

loads are simply able to dedicate more time, and thus a higher percentage of

their income is generated from MC services. Chiropractors, like all health care

providers, must meet financial obligations and must charge for their services.

It is reasonable to expect that they would focus on services for which they can

expect reimbursement. MC, which is not covered in the United States by most

health insurance, Medicare, or worker's compensation programs, is not one of

those services. Therefore chiropractors with high volumes of patients with

low-back pain and other reimbursable conditions might be less likely to spend as

much time on services for which reimbursement is difficult, such as MC.

Composition of MC

Previously, no data existed that described the therapeutic constituents of

MC. Recently, there has been speculation by authors that chiropractors “keep

people well through spinal adjustments”31

and that diet, exercise, lifestyle changes, and other prevention-directed

activities are not part of the profession's prevention efforts. This view

appears inaccurate because this study depicts the preventive MC activities of

chiropractors as a combination of interventions that rely heavily on exercise,

nutrition, and lifestyle changes. Although most doctors (96.7%) responding did

agree that spinal manipulation was an essential component of preventive MC

services, the respondents also agreed that exercise was an equally important

component (96.1%), followed closely by proper eating (92.8%), patient education

(83.6%), and vitamin and supplement usage (67.1%).

Value of maintenance care

To ensure a response from field doctors, the questionnaire was only 1 page.

Because of the short length of the questionnaire, there were only 4 age groups

of patients listed: children, adolescents, adults, and the aged. The survey

described a consensus about the value of MC for all 4 patient groups. This was a

consistent response, considering the high percentage of patients recommended to

receive MC. In addition, there is a prevalent belief that preventive MC services

are helpful in a variety of visceral conditions and musculoskeletal problems.

Because of the eclectic nature of the therapies used in MC and because it is

standard medical practice to make exercise, nutritional, and other

recommendations for many visceral problems, it is not surprising that

chiropractors would also address these conditions. It was beyond the scope of

this initial study to ascertain to what extent chiropractors believe specific

visceral and musculoskeletal conditions benefit specific therapeutic components

of MC. Five different purposes for MC were given with this survey. Relatively

strong agreement was found for all but 1 (ie, the prevention of subluxation).

Slightly more than half of chiropractors believed MC was valuable for this

purpose. This response raises questions about the belief system of chiropractors

because it relates to prevention and the subluxation concept. If MC cannot

prevent subluxation, how is it prevented? Future studies should be directed at

exploring wellness and prevention in the context of subluxation.

Research

The 658 doctors who responded to the survey were relatively unaware of the

scarce research that supports the use of MC. Forty percent believed that

“chiropractic research adequately supports the value of MC” and <7% strongly

disagreed with that statement. This misconception exists despite the fact that

the deficiency in supporting research has been brought to the profession's

attention on many occasions by both the medical community and those involved in

chiropractic research. 32–35

The survey did establish that the overwhelming majority (93.4%) of the

profession agreed that there was a need for further research. The research issue

questions the education of chiropractors as it relates to MC. Future research

should be directed at why there is such a strong belief in the value of the

spinal manipulation component of MC among both new and established

chiropractors. In what manner is this subject addressed in chiropractic colleges

and to what extent does practice experience have an impact on the belief in MC?

One reason why chiropractors may believe that adequate research exists is simply

because, as this survey suggests, MC includes a wide variety of well-researched

health promotion components, including exercise, food supplementation, and

diet.

The chiropractic profession has had a historic interest in and emphasis on

health promotion and prevention, often referred to as MC. The literature to date

consists primarily of individual opinions that, based on this work, have often

misrepresented the motivation, therapeutic components, extent of use, and other

elements of MC. The respondents to this survey, like their European and

Australian counterparts, strongly believe in the preventive and health-promoting

merits of periodic visits for MC. MC is believed to benefit patients of all ages

for a wide variety of visceral and musculoskeletal conditions. Belief in the

efficacy of MC translates into a high rate of recommendation to patients and a

substantial economic impact on chiropractic practice. Although chiropractors

with low new patient traffic tended to recommend MC services more often, both

chiropractors with low and high new patient traffic believed that MC was

valuable for promoting patient health. The recommendation that patients receive

MC was also not related to practice income from MC. Therefore the belief in the

value of MC appears to be motivated by its potential value to the patient and

not for financial gain as some have suggested. Chiropractors concur that MC is

not simply administering periodic manipulative treatments but rather that

exercise, nutritional, and lifestyle recommendations are equal or nearly equal

in importance.