| Periodicals Home | Search | User Pref |

Help | Logout |

| JMPT Home | Current Issue |

All Issues |

Order | About this Journal |

<< Issue |

>> Issue |

| Periodicals Home | Search | User Pref |

Help | Logout |

| JMPT Home | Current Issue |

All Issues |

Order | About this Journal |

<< Issue |

>> Issue |

|

Ronald L. RupertDC,a [MEDLINE LOOKUP]Sections |

|

| Abstract | TOP |

| (Click on a term to search this journal for other articles containing that term.) |

| Key Indexing Terms:

Chiropractic,

Health

Promotion, Physician's

Practice Patterns, Primary

Health Care, Preventive

Health Services, Primary

Prevention |

| Introduction | TOP |

The definition and criteria for primary care established by the National Academy of Science included the need for the physician to “motivate and guide the patient to achieve and maintain a state of health with considerations of wellness and disease prevention.”1 The need for these health-promotion and prevention services has not only been recognized by the medical profession but has long been embraced by chiropractors.2 Also, there is a growing belief expressed by both professions that socioeconomic forces affecting health care in the United States are causing a paradigm shift that places less emphasis on treatment and more on prevention and wellness. 3–6 This will likely create a greater future need for effective preventive and health-promotion services.

Historically, chiropractors have advocated periodic office visits for the purpose of prevention and health promotion. These services have often been referred to as maintenance care (MC).7 Previous studies confirm that chiropractors do engage in health-promotion activities, such as screenings and patient counseling related to issues, such as diet, smoking, exercise, and alcohol use. 8–11 Recent research has attempted to define more clearly the exact nature or therapeutic constituents of MC, particularly the role of manual procedures, such as spinal manipulation.12 Despite the acceptance of MC by much of the chiropractic profession, 12–14 the value of these health maintenance services repeatedly has been questioned and criticized by the medical community and government agencies. 15,16 As the New Zealand commission of inquiry noted, “…medical or dental check-ups may produce evidence of identifiable disorders whose results can be predicted with a reasonable degree of certainty. The Commission does not consider that the same can be said of chiropractic ‘preventative’ check-ups, at least in the present state of scientific knowledge.”16

Neither these criticisms nor the lack of research supporting the concept of chiropractic MC have deterred its widespread use. 12,17–18 In fact, chiropractors may administer more prevention and health-promotion services than any other health profession. The results of Part 1 of this study suggest that 79% of chiropractic patients receive the recommendation for MC, and 23% of all practice incomes relate to these services.12

There has been a significant increase in the number of elderly persons in the United States,19 and in the future, life expectancy is also projected to increase.20 Currently, the population over age 65 years accounts for over one third of all health care expenses.20 Elderly patients with chronic problems have a disproportionately higher cost associated with their care.21 Chiropractors see a significant number of these elderly patients with chronic health problems.22 These socioeconomic dynamics will create a greater potential patient pool for future chiropractic care. Although there appears to be a strong professional belief in MC,12 some empirical support for its value,13 and a significant amount of income derived from its administration,12 there has never been an attempt to create a descriptive profile of the patient receiving MC or to study the benefits of any of these prevention programs. It is essential that the chiropractic profession evaluate the efficacy of its prevention and wellness efforts, particularly in the elderly who constitute the largest growing segment of the population and the most significant financial burden on the health care system.

The primary purpose of this research was to conduct a descriptive study of patients age 65 years and over who have received extended chiropractic preventive and health-promotion management (MC). Specific objectives included the following:

| Methods | TOP |

Literature searches were conducted through MANTIS and MEDLINE in much the same manner as described in Part 1 of this study. Separate searches were also conducted through the Internet where extensive health data compiled by the US Government and other organizations is made available. Much of the epidemiologic data related to the United States was accessed through the MedAccess Corporation, which makes information from statistical abstracts available (www.medaccess.com/census/c_03.htm).

A pilot study using a convenience sample of 15 doctors and 84 patients from 4 sites (California, Missouri, South Carolina, and Texas) was conducted as the initial part of this research.23 The pilot study aided in the evaluation and revision of test instruments and research protocols used in this investigation. The protocol for the pilot study, as well as that for the full-scale study reported here, was reviewed and approved by an institutional review board to insure protection of human subjects. The current study attempted to select and evaluate a heterogeneous sample of US patients receiving chiropractic health-promotion and prevention services. The evaluation process included using multiple test instruments administered to the patients to collect information regarding health status, health habits, cost of and satisfaction with care, and related issues. The treating doctors also completed a questionnaire that provided data related to type, frequency, and duration of previous care. Specific selection methods, assessment instruments, and protocols follow.

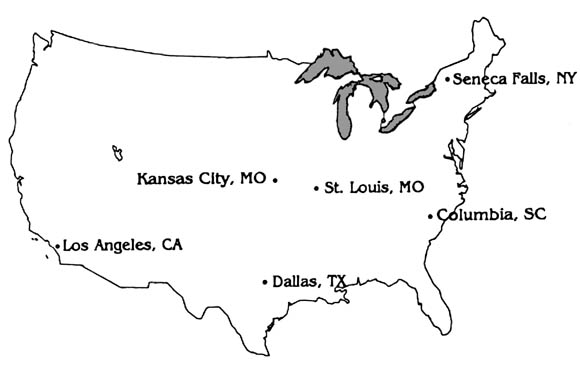

Doctor selectionTo identify patients who had received MC, to collect details of MC treatment for each patient, and to facilitate patient data collection, it was necessary to recruit the assistance of practicing chiropractors. To minimize the possibility of bias from geographic variations in chiropractic patients or regional differences in physician practice patterns, 6 geographically diverse US sites were selected for the study (Fig 1).

|

Fig. 1. Geographic disbursement of 6 MC test sites. |

|

|

|

A scripted telephone protocol was used to contact all practicing chiropractors within geographic proximity of the 6 sites. The script briefly described the nature of the research and ascertained whether the chiropractor met the inclusion criteria. These criteria required the following of each doctor: (1) they must have provided prevention and health promotion services (MC); (2) they must have been in practice for at least 5 years or currently be managing patients who have been under preventive care for at least 5 years (and have access to those patients' past treatment records); and (3) they must agree to assist with the research. All chiropractors meeting these criteria were placed in a pool from which they were randomly selected at each of the 6 sites. Drawing names was the most common method used for random selection. At some sites, because of unwillingness or limited ability of doctors to participate, the site manager was required to use virtually all chiropractors who volunteered. The selected doctors completed a survey related to their MC attitudes and practice patterns, which permitted comparison with a previously conducted national survey. Training and materials were provided by each site manager for both selected doctors and staff. This training was accomplished in meetings, by phone, and in some cases necessitated one or more physical visits to each doctor's clinic. Follow-up telephone support, postal support, or both was also required. The site managers and their staff became the portal of access to patients receiving MC and also provided information regarding the frequency and duration of treatment, as well as details about what specifically constituted treatment for each patient.

Patient selectionThe nature of MC involves the interaction of patient and doctor over time, and patients just beginning this process would not have had time to demonstrate health status changes. Therefore an inclusion criteria was used that required that patients receive MC for at least 5 years and therefore that the doctor be in practice for at least 5 years or have access to the last 5 years of the patients' records. The only other inclusion criteria were that the patient be age 65 years or over and that participation was voluntary. This research targeted an older patient population (1) because older patients generally have more health problems; (2) because of their age, these patients would have a greater potential to have had an extended regimen of MC; and (3) because this subset of the US population is projected to dramatically increase over the next decade and poses the greatest financial burden to the future cost of health care.20

Because there is no evidence that patients receiving MC make visits to chiropractic offices in any predetermined order (eg, by age, sex, or race), doctors and their staff were asked to select the first 10 consenting patients meeting the inclusion criteria. These patients were asked to complete the instruments described below in the doctor's office if possible. For some patients, questions related to issues like the number of doctor visits in the previous year or the cost of health care services required them to refer to home records and return or call their chiropractic provider to complete the questionnaire.

Assessment instrumentsPatients were asked to complete a general health status survey, the SF-36D and a supplemental questionnaire. The SF-36D was selected because of its widespread use in both medical and chiropractic research, 24–26 its established reliability and validity,27 and the normative data that exists for US patients age 65 years and over.28 The survey also includes basic patient demographics (ie, age, sex, race, and education). The SF-36D gives the overall health status index of a patient and further breaks health down into 3 primary attributes: functional status, well-being, and overall evaluation of health. There are also 8 health concepts evaluated: physical function, mental health, role physical, energy, role mental, pain, social function, and health perceptions. The SF-36D was also selected because of these multiple diverse scales, which could provide some indication of where significant differences in patients receiving MC might exist. This in turn would allow selection of more sensitive instruments that might be used in future research to discern those differences.

The supplemental survey was also completed by each patient. These questions were directed at lifestyle-health habits, medical use, health care costs, and perceived value of chiropractic MC. The first 7 questions of this patient survey used an ordinal 5-point Likert scale to evaluate lifestyle and health habits that are associated with prevention and health promotion (ie, the frequency of use of stretching exercises, aerobic exercises, alcohol, vitamins, nonprescription drugs, use of tobacco, and relaxation). The remaining 7 fill-in questions provided information describing the total health care expenditures, number of surgeries, physician visits, and other use issues during the prior year. The final Likert format question asked the patient to evaluate how important chiropractic treatment was to maintaining and promoting their health.

The third instrument used for data collection was completed by the treating physician for each patient receiving MC. It provided data describing the frequency and duration of the patient's MC, as well as specific treatments used in the care of the patient. The doctor also described the components of MC for each patient, including the possible use of manipulation, exercise, nutrition, and/or physical therapy.

The doctor also completed a general MC questionnaire that described their attitudes toward and the extent to which they use MC in their practices. This MC questionnaire was identical to that used in Part 1 of this study and permitted a comparison with the national survey to determine whether any significant differences existed between the participating chiropractors in this investigation and those in the national survey.

Data analysisVersion 7.5 of SPSS for Windows was used for both data entry and analysis. Data entry screens were created by the principal investigator, and data entry was monitored to insure accuracy. Patient data required 29,070 entries and another 2920 data points related to doctor demographics and practice patterns (total of 31,990 entries). All precoded values for the patient responses to the SF-36D were then coded and subsequently scored. Relationships between variables were evaluated by using bivariate correlation procedures (Pearson or Spearman). Missing data were managed by excluding cases in a pairwise manner, which provided correlations on the basis of cases where data was available for both variables.

| Results | TOP |

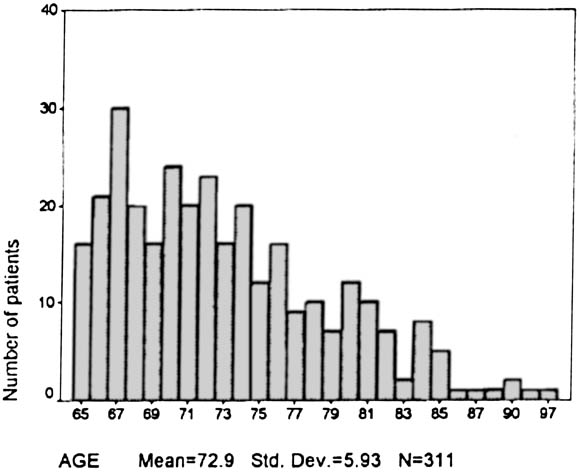

A total of 311 patients receiving MC who met the inclusion criteria were accessed through 73 doctors from the 6 study sites. Data were collected over a period of 7 months from March 1995 through November 1995. The average number of patients per doctor was 4.26, with a range of 14.

DemographicsThe sex, race, education level, and related characteristics taken from the

SF-36D completed by all patients receiving MC are reflected in Table 1.

| Characteristics | Patients receiving MC* (n = 311) | Characteristics | Patients receiving MC* (n = 311) |

| Age (y) | Marital Status | ||

| Minimum | 65 | Never Married | 6.8% |

| Maximum | 97 | Married | 59.8% |

| SD | 5.93 | Separated-divorced | 5.1% |

| Widowed | 28.3% | ||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 66.9% | ||

| Male | 33.1% | ||

| Race | Education | ||

| Black | 2.6% | Completed 8th grade | 8.7% |

| White | 96.1% | Some high school | 14.5% |

| Asian | 0.3% | Finished high school | 32.3% |

| American Indian | 0.3% | Some college | 22.8% |

| Other | 0.6% | College graduate | 12.5% |

| Postgraduate | 9.3% | ||

*Sample from California, Kansas, Missouri, New York, South Carolina, and Texas. | |||

|

Fig. 2. Age distribution of chiropractic patients receiving MC. |

|

|

|

The results of the national survey of MC attitudes and practice patterns

(Part I) provided a basis for comparison with the 73 chiropractors who

participated in this study. There was a higher percentage of female participants

in this study than responded to the national survey (21.9% and 16.6%,

respectively). Table 2 provides a comparison of several key demographic and

practice issues related to the 73 doctors participating in this study versus

those participating in the national survey.

| National doctor survey (n = 658) | MC-treating doctors (n = 73) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 83.4% | 78.1% |

| Female | 16.6% | 21.9% |

| Age (y) | ||

| Mean | 44.0 | 41.82 |

| Years in practice | ||

| Mean | 12.33 | 14.73 |

| New patients per mo | ||

| Mean | 19.5 | 18.38 |

| Patients advised to have MC | 78.7% | 81.9% |

| Patients actually receiving MC | 34.4% | 35.6% |

| Practice income from MC | 22.9% | 26.3% |

| Average No. of visits per month for MC | 14.4 | 15.9 |

The health status of patients receiving MC on the basis of the various scales

from the SF-36D is reflected and compared with a sample from the general

population in Table 3.

| Scales (SF-36D) | Sample receiving MC (n = 311) | Sample not receiving MC (n = 1814) |

| Physical function | 68.4 (24.3)* | 62.7 |

| Role physical | 60.9 (39.8) | 51.9 |

| Role mental | 80.9 (31.5) | 72.9 |

| Social function | 86.7 (18.5) | 80.0 |

| Mental health | 79.9 (15.1) | 77.1 |

| Energy | 61.0 (20.8) | 56.4 |

| Pain | 66.6 (22.5) | 67.2 |

| Health perceptions | 68.9 (19.7) | 62.5 |

| Positive depression screener | 16.6% | 89% |

| Maximum possible score for all scales is | 100 | |

*Values in parentheses indicates SD. | ||

The depression screening portion of the SF-36D consists of 3 questions. The developers of the SF-36D have conducted large community studies and noted that a high percentage (as much as 89%) of the adult population was identified with a “psychiatric diagnosis of major depression or dysthymia.”26 Of the 301 patients receiving MC who completed the depression scale, only 16.6% were identified as having major depression (n = 49) or dysthymia (n = 1). The demographics of the subjects used to create the normative data supplied by the developers of the SF-36D are too dissimilar to permit comparison with the elderly patients receiving MC described in this work. However, trends toward lower depression are corroborated in a previous evaluation of elderly patients (not patients receiving MC), which did indicate a “nonsignificant trend for chiropractic users to report fewer depressive symptoms.…”24

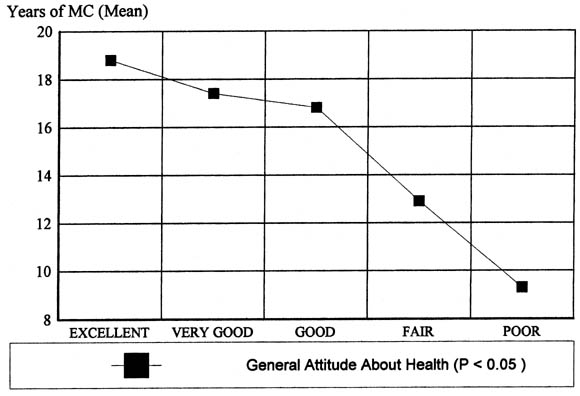

Another important use of the SF-36D in this study was to investigate for possible changes in the scores from the various scales relative to the number of years the patient had received MC. The first question of the SF-36D asks the patient to give an overall assessment of their health. The question is framed as follows, “In general, would you say your health is:,” and permits 5 possible responses ranging from “excellent” to “poor.” There was a significant correlation (P < .05) between the perceptions of patients receiving MC of how good their general health status was and the number of years they received MC (Fig 3).

|

Fig. 3. Patients' responses to SF-36D statement “In general, would you say your health is.…” (relative to years of MC). |

|

|

|

The elderly patients receiving MC in this study did not rely solely on

chiropractic care but used both medical and chiropractic services. These

services are summarized in Table 4.

| Medical use | Mean | Source |

| No. of current prescription medications | 2.03 | Patient |

| No. of surgeries the previous year | 0.23 | Patient |

| Physician visits (medical) | 4.76 | Patient |

| Physician visits (chiropractic) | 16.95 | Chiropractor |

| Days hospitalized (previous year) | 1.23 | Patient |

The treating doctors were also asked to select, from a limited list of

specific chiropractic techniques, the techniques that were used in each

patient's care. Most doctors reported using a variety of treatment interventions

for the management of the elderly patients receiving MC investigated in this

study. Previous research had identified the Diversified technique as the most

commonly used by the profession.30

It was the most commonly used procedure for patients receiving MC, with 70.9%

treated with the Diversified technique. Each patient averaged receiving 1.9

chiropractic procedures (eg, soft tissue/Nimmo, Diversified, Gonstead, or AK;

Table 5).

| Method of manipulation | No. of patients | Percentage of patients* |

| Activator | 88 | 28.3 |

| AK | 50 | 16.1 |

| Diversified | 219 | 70.4 |

| Gonstead | 55 | 17.7 |

| Grostic | 5 | 1.6 |

| Nimmo/other soft tissue | 64 | 20.6 |

| SOT | 42 | 13.5 |

| Thompson | 68 | 21.9 |

AK, Applied kinesiology; SOT, sacro-occipital technique. *Mean number of procedures per patient = 1.9 | ||

| Interventions-recommendations | No. of patients | Percentage of patients* |

| Stretching exercises | 212 | 68.2 |

| Cardiovascular exercises (eg, walking or swimming) | 173 | 55.6 |

| General diet advice (eg, reduce fat and sodium) | 141 | 45.3 |

| General vitamin-mineral advice | 128 | 41.2 |

| Condition-specific dietary treatment advice | 81 | 26.0 |

| Physical therapy | 109 | 35.0 |

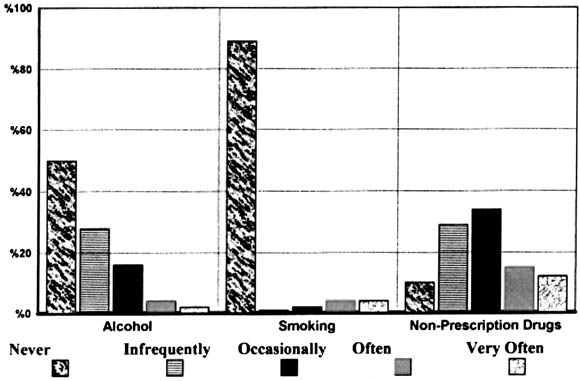

An overview of some personal habits that may have an adverse effect on health appears in Fig 4.

|

Fig. 4. Levels of involvement of patients receiving MC with activities that may adversely effect health. |

|

|

|

|

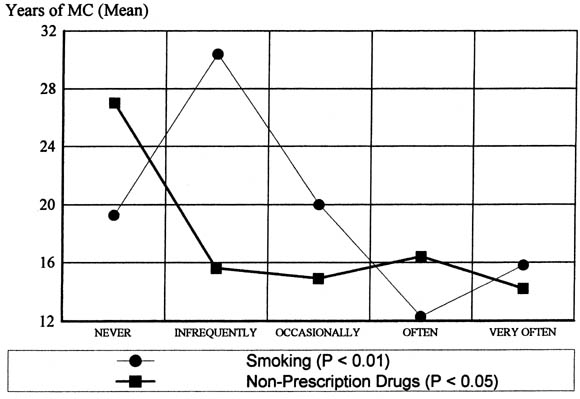

Fig. 5. Patients' smoking and nonprescription drug use relative to years of MC. |

|

|

|

|

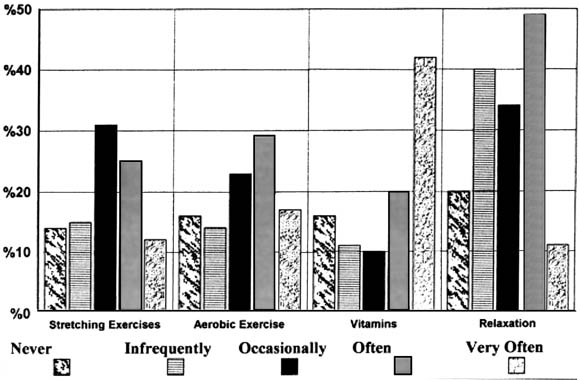

Fig. 6. Levels of participation of patients receiving MC in health-promoting behaviors. |

|

|

|

The estimated average health care costs for US citizens 65 years of age or

older in 1994 is conservatively estimated to be $10,041. This was derived by

taking the last year that the government calculated per capita expenses for

patients age 65 years and over, which was $536033

in 1987, and multiplying those expenses by the average percentage of growth in

health care costs provided by the government from 1987 to 1994 (11.9% in 1988,

11.2% in 1989, 12.1% in 1990, 9.2% in 1991, 9.5% in 1992, 6.9% in 1993, and 5.1%

in 1994).34

The literature indicates that the greatest growth in health expenditures is for

those age 65 years and over, and therefore the estimated annual health cost of

$10,041 is likely an underestimation of the actual expenditures. 20,35

The annual health care cost associated with the subjects receiving MC who were

age 65 years and over included in this study was $3106 (1994 dollars; Table

7).

| Source | Mean annual expense | Non-MC mean annual expense |

| Hospital care | $1723.22 | $5121 |

| Physician's services (including chiropractic) | $1372.76 | $4920 |

| Nursing home | $9.83 | |

| Total | $3105.81 | $10,041 |

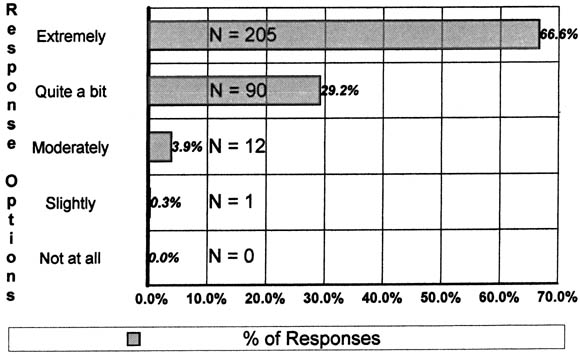

The question “How important do you feel chiropractic treatment has been in maintaining and promoting your health?” was asked of all patients. The response reflects a very strong regard for such treatment, with 95.8% believing it to be either considerably or extremely valuable (Fig 7).

|

Fig. 7. Patients importance of MC in “maintaining and promoting health.” |

|

|

|

| Discussion | TOP |

Caution must be exercised when reviewing some of the results of this investigation. A few questions required data to be supplied by patients receiving MC that was not verifiable, and errors in either overestimation or underestimation in their reporting may have occurred. The reported significant correlations and the correlations that approach significance suggest that a relationship exits between variables. However, correlations do not confirm that a cause-and-effect relationship exists. Although it is possible that MC provides benefit, it is also possible that significant differences may be due to the inherent differences in the population samples or other uncontrolled variables. For example, the reduced smoking seen with patients receiving long-term MC may be primarily due to the overall trend in society to reduce cigarette consumption. Future research will be required to explore and establish the possible cause-and-effect relationship that might exist between MC and improvements in patient health.

As other researchers have noted, the motivation of participating doctors and staff is difficult but imperative to the success of this type of study.38 Great effort was expended to recruit and train chiropractors for this work; however, despite these efforts several difficulties arose. One problem involved doctors who initially expressed a desire to participate, were trained along with their staff, but dropped out as increased workloads prohibited their involvement. On several occasions doctors would lose staff, and retraining would have to be accomplished. Additionally, all sites had a few chiropractors who volunteered and were trained, but during the data collection period, had no patients meeting the inclusion criteria. These issues resulted in the need to train or dedicate efforts to retrain more doctors and staff than originally anticipated. These problems did not result in a degradation in the quality of data collected but did reduce the total number of subjects evaluated.

When initially contacted to participate in research, many chiropractors were either not eligible or expressed no desire to become involved. This same lack of cooperation by the chiropractic profession has been discussed previously by other researchers and most recently in another study involving chiropractic treatment of the elderly.22 The majority of chiropractors who elected not to assist with this study did report providing various levels of MC services. The three most common reasons for not participating were that they were (1) too busy, (2) not in practice long enough to have patients under care for 5 years, or (3) just did not have many elderly patients. A larger sample size would provide a greater assurance that the patient sample was representative. This study did build in a measure of assurance that the doctors used in this work were representative of chiropractors nationally. Each participating chiropractor, as described earlier, completed the same questionnaire, which provided a profile of beliefs and practice patterns related to MC. With the exception of a greater participation of female chiropractors, the demographics were similar to those of the national survey. Most importantly, there were no significant differences in attitudes or practice patterns between the 73 doctors participating in this study and the doctors randomly selected for the national survey. The multicenter design, seeking geographic diversification of doctors and patients, also provided a greater likelihood of obtaining a representative sampling.

Another limitation of this work was the selection and design of assessment instruments. Because there had been no previous attempt to evaluate patients receiving MC, it was not possible to know which assessment instruments would most likely demonstrate potential differences if indeed differences in these patients compared with other population samples did exist. The authors attempted to use a brief and diverse range of measurements for a broad sampling of areas in which distinctive characteristics of patients receiving MC might be identified. It is quite possible that other instruments might have been more suitable or that, as others suggest, new assessment instruments might be necessary to evaluate these patients.39 It was believed that although the development and validation of new measuring devices may indeed demonstrate greater differences or potential value from MC care, there were a number of accepted instruments that should be explored before the expensive and time-consuming process of new test development is undertaken. There were also some limitations in survey design of some of the test instruments. To not discourage participation by either doctors or patients, the length of questionnaires had to be kept reasonably brief. This necessitated limiting fields and choices (eg. the number of chiropractic techniques listed or the list of other interventions that might have been used in patient care). The need for brevity also limited the use of other instruments that, in retrospect, may have been superior to those used. For example, the SF-36D data suggest a low level of depression among patients receiving MC; future studies should explore this finding with some of the many instruments available for that purpose.

It is not known how long a regimen of MC is required before differences, if any, could be measured. Clearly, the very nature of MC requires an ongoing doctor-patient relationship. Patients who are newly enrolled in an MC regimen would not have had time for any changes to have occurred resulting from MC treatment. Five years of care was considered a reasonable starting point for patients in this study. However, it is possible that because of the advanced age of the patient population targeted for this study and the often chronic, long-standing problems they encounter, that 5 years would not be a sufficient amount of time for MC to make changes in the patient's overall health status. Five years of care cannot remove 65 or 70 years of health abuse, and there may have been more substantial changes observed if more data could have been obtained for patients who had a longer regimen of MC management. However, considering the substantial problems that the investigators had in recruiting doctors and patients meeting the various existing inclusion-exclusion criteria, additional patients receiving long-term MC would have been extremely difficult to obtain.

There were weaknesses in the design of some of the 7 supplemental questions related to health habits. Question design could have been improved if an operational definition or a more specific grounding had been given for terms like “relax.” Also, it would have been more useful to ask patients how much alcohol they drank in a specific period of time rather than how often they drank alcohol. An important financial issue is whether chiropractic care for the elderly simply adds to or reduces the total cost of health care. This is certainly a significant matter for both those who argue that chiropractic services may serve to augment the insufficient number of primary care medical providers, as well as those who argue that chiropractic complements and adds to the cost of health services. Several medical reports suggest that chiropractic visits do not replace nonavailable medical services. 40–42 One such article reviews patient patterns in Manitoba, Canada (1983). Manitoba is a province that fully insures the elderly for medical services but only provides a limited number of chiropractic services. The study concluded that “chiropractic services do not substitute for physician services among the elderly.”40 In addition to chiropractic visits, patients with chronic conditions also made more medical visits.40 The work of Coulter et al22 with chiropractic patients over 65 years of age had essentially the same finding: visits to the chiropractor are not associated with a reduction of the number of visits to the medical physician. All of these previous investigations evaluated all chiropractic patients 65 years of age and older, whereas this study focused on only those patients who had been enrolled in a long-term health promotion and prevention doctor-patient relationship of at least 5 years. The findings of this study contrast with those of these previous works. One explanation of this difference is that there may be a distinct profile and dynamic involving elderly patients who supplement medical care with chiropractic visits (which may add to and not reduce medical management) versus the patient who relies heavily on chiropractic treatment for long-term primary care services. The former category of patient continues to maintain the same level of medical management, whereas the second (like the patients receiving MC in this study) may supplant half of the medical management with chiropractic care. The chiropractors who participated in this study had many patients over 65 years of age who were being seen for management of an acute condition and therefore did not meet the inclusion criteria. For these acute care patients, the chiropractor may serve as a specialist and complements the health management of the patients' primary care provider. On the other hand, there are patients, such as the patients receiving MC reported in this study, who rely on the chiropractor for prevention, health promotion, and other primary care services. It appears that these patients receiving MC require far less medical intervention. This study did not investigate the extent to which medical visits made by patients receiving MC might have been the result of referral from the chiropractor or from the medical provider to the chiropractor.

There is normally an association between the number of physician visits and the total cost of health services. However, this might not be true if the office visits were part of an effective prevention and health-promotion program that reduced other more costly health care services. The cost of health care for patients receiving MC in this study was far less than that for patients of similar age in the general population despite the doubling of physician visits (medical plus chiropractic). The greatest difference in health care costs with patients receiving MC was in the areas of nursing care and, especially, hospital care. This reduced need for hospital and nursing home services has recently been corroborated by the research of Coulter et al.22 Because of limitations in both the objectives and design of this study, it is not possible to establish a causal relationship between the use of MC and the overall difference between health expenses of patients receiving MC and those of patients not receiving MC. This study describes several improved health variables associated with increased years of chiropractic MC management. These include improved perception of overall health status, improved health habits, and improved mental status. Several factors beside MC (eg, patient self-selection) could account for this finding. If MC is responsible for these changes, it is not clear which therapeutic interventions or other elements of this care fostered the patients' improved health. Some of the important elements of MC include the long-term chiropractic doctor-patient relationship, which embodies much of the relationship-oriented holism discussed by other authors. 43,44 MC incorporates an eclectic variety of components, which include a high number of doctor-patient encounters over an extended period of time and a variety of therapeutic interventions. The doctor-patient relationship itself has many dynamics that may combine to account for the apparent benefits of MC; these include the validation of the patient complaint, the effects of human touch, the placebo effect, the increased opportunity for patient education, and counseling and other factors. 45–47 In this regard chiropractic MC is a unique patient experience and quite different from the typical medical encounter. The extended duration of the doctor-patient relationship much more closely resembles that with the primary care provider than the limited number of visits common with medical specialists. MC treatment differs from orthodox medicine; it relies on multiple manual procedures for each patient, an emphasis on exercise and diet, and a variety of other interventions.

Along with health status questionnaires like the SF-36D, other existing assessment instruments will need to be used or perhaps developed and tested to more thoroughly investigate long-term chiropractic preventive management. Because of the findings that significantly correlate reduced nervousness with years of MC, as well as possible reduced symptoms of depression, additional psychologic instruments would be of particular interest for future research. Another general research problem that must be addressed is the reluctance of practicing chiropractors to become part of research efforts. This study required a minimal contribution in the doctor's time, yet few were willing to participate. On the basis of the degree of difficulty experienced in recruiting chiropractors for this and other studies, better strategies to recruit, educate, and perhaps reward chiropractors need to be explored before more demanding investigations of MC will be feasible.

| Conclusion | TOP |

On the basis of clinical information provided by the treating chiropractor, most patients receiving MC receive an eclectic variety of therapeutic interventions, which usually include manipulation, exercises, and patient education relative to diet, vitamins, and other health issues. In addition to prevention and health promotion, MC visits are directed at a variety of musculoskeletal, as well as visceral, conditions.

The responses of the 311 patients involved in this study demonstrated a significant positive correlation associated with the patients' perception of health status and the number of years of MC. Where data related to the health habits of US citizens 65 years of age and over existed, the health habits of patients receiving MC were similar to or better than those of the general population. There were positive correlations with both the decreased use of cigarettes and decreased use of nonprescription drugs and the number of years of MC.

There appears to be a subtle difference in the nature of the doctor-patient relationship that exists between chiropractic patients who receive MC management and chiropractic patients who do not, as well as differences between patients receiving MC and those elderly patients who receive no chiropractic care at all. These differences in patients receiving MC included the number and mix of office visits to various health providers. Patients receiving MC had twice as many contacts with a physician during the year than patients who receive no chiropractic care at all. These doctor-patient contacts are primarily for chiropractic MC care and result in a 50% reduction in medical provider visits. Therefore for these patients receiving MC, chiropractic management appeared to replace medical management rather than be complementary to medical treatment. This contrasts with previous work, which demonstrated that elderly chiropractic patients, including both those who do and those who do not receive MC, actually made more visits to medical providers in addition to their chiropractic visits. The need for hospitalization and the high costs associated with that service were markedly reduced for the patient receiving MC. The total annual cost of health care services for the patient receiving MC was conservatively estimated at only a third of the expenses made by US citizens of the same age. Patients also perceived MC services as highly beneficial to prevention and health promotion. Future research will need to determine whether the positive relationships that are associated with patients receiving MC and extended duration of MC care are directly related to the chiropractic services provided, population differences, or other variables.

We wish to acknowledge the notable contribution of the various test site managers, as well as their respective colleges or organizations: J. Miller, DC, New York Chiropractic College; R. Zatkin, PhD, Cleveland Chiropractic College-LA; and Janet Jordan, South Carolina Chiropractic Association.

| References | TOP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Publishing and Reprint Information | TOP |

| Articles with References to this Article | TOP |

|

|

|