Best Practices for Chiropractic Care of Children:

A Consensus UpdateThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016 (Mar); 39 (3): 158–168 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Cheryl Hawk, DC, PhD, Michael J. Schneider, DC, PhD, Sharon Vallone, DC, Elise G. Hewitt, DC

Executive Director,

Northwest Center for Lifestyle and Functional Medicine,

University of Western States,

Portland, ORThis is an update of the 2009 Consensus Document titled:

Best Practices Recommendations for Chiropractic Care for Infants, Children, and Adolescents

According to the authors of the update

Editorial Comment:“All of the seed statements in this best practices document achieved a high level of consensus and thus represent a general framework for what constitutes an evidence-based and reasonable approach to the chiropractic management of infants, children, and adolescents.”

“There are myths that chiropractic care is only for adults. So, it is with great pleasure we share the following open-access paper, published by an outstanding team of scholars and experts on best practices for chiropractic care of children. This paper is a must read for practicing DCs, chiropractic students and for that matter, anyone who comes into contact with children.”

OBJECTIVE: Chiropractic care is the most common complementary and integrative medicine practice used by children in the United States, and it is used frequently by children internationally as well. The purpose of this project was to update the 2009 recommendations on best practices for chiropractic care of children.

METHODS: A formal consensus process was completed based on the existing recommendations and informed by the results of a systematic review of relevant literature from January 2009 through March 2015. The primary search question for the systematic review was, "What is the effectiveness of chiropractic care, including spinal manipulation, for conditions experienced by children (<18 years of age)?" A secondary search question was, "What are the adverse events associated with chiropractic care including spinal manipulation among children (<18 years of age)?" The consensus process was conducted electronically, by e-mail, using a multidisciplinary Delphi panel of 29 experts from 5 countries and using the RAND Corporation/University of California, Los Angeles, consensus methodology.

RESULTS: Only 2 statements from the previous set of recommendations did not reach 80% consensus on the first round, and revised versions of both were agreed upon in a second round.

CONCLUSIONS: All of the seed statements in this best practices document achieved a high level of consensus and thus represent a general framework for what constitutes an evidence-based and reasonable approach to the chiropractic management of infants, children, and adolescents.

KEYWORDS: Adolescent; Chiropractic; Infant; Manipulation; Pediatrics; Spinal

From the Full-Text Article:

Introduction

Chiropractic is a health care profession concerned with the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disorders of the neuromusculoskeletal system and the effects of these disorders on general health. [1] Chiropractic care is the most common complementary and integrative medicine practice used by children in the United States. [2] A recent Gallup survey found that approximately 14% of US adults reported that they had used chiropractic care in the prior 12 months, that more than 50% had ever used a doctor of chiropractic (DC) for health care, and that more than 25% would choose chiropractic care as a first treatment for neck or back pain. [3] The findings from this survey also were consistent with a previous study that found that patients use chiropractic services in different ways, sometimes for treatment and sometimes for health promotion. [4]

Internationally, chiropractic is frequently used by children. [5–11] Chiropractic care for children is most often sought for treatment of musculoskeletal conditions, except in the case of infants, where infantile colic is one of the more common presenting complaints. [5, 9] In the United States, parents also frequently seek chiropractic care for their children for “wellness care”; and it has been found, that in general, children with a decreased health-related quality of life have a higher utilization of complementary and integrative medicine. [8, 12] However, the scientific evidence for the effectiveness and efficacy of chiropractic care and spinal manipulation for treatment of children is not plentiful or definitive. [13–15]

To address the gaps in the literature, in 2009, we performed a consensus process gathering expert opinion on best practices for the chiropractic care of children. [16] The resulting document has been helpful in providing chiropractic practitioners with guidelines for pediatric care. It has also been useful for other types of providers, the public, and third-party payers in demonstrating that the chiropractic profession has standards for pediatric care. However, this document was based on the literature published before 2009, so in keeping with recommendations for guidelines, [18, 18] we launched the current project. The purpose of this project was to update the existing set of recommendations on best practices for chiropractic care of children by conducting a formal consensus process. The process was based on the existing recommendations and informed by the results of an updated literature review.

Training of DCs in Pediatrics

The chiropractic profession holds the responsibility of ethical and safe practice and requires the cultivation and mastery of both an academic foundation and clinical expertise that distinguish chiropractic from other disciplines. [1]

Chiropractic undergraduate education includes the study of the unique anatomy and physiology of the pediatric patient as well as the modification of evaluative and therapeutic procedures as it applies to this special population when addressing musculoskeletal problems and their effect on the overall health and well-being of the child. Specialty interest groups were founded in chiropractic colleges (pediatric clubs) as well as on a national and international association level, ultimately leading to the development of postgraduate curricula to provide advanced training for DCs who chose to develop their clinical skills in pediatrics. [19] There now exist several postgraduate titles including a Diplomate (USA/NZ) or a Masters in Science (MSc)/Pediatrics (UK).

Methods

Human Subjects Considerations

Before the start of the project, this project was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Logan University and University of Western States. Participants gave written permission for the use of their names in any publication related to the project.

Steering Committee (SC)

A steering committee was formed to provide a multidisciplinary perspective, ensuring that key stakeholders were represented, with members representing medicine (2 pediatricians, 1 a DC/MD), chiropractic practitioners and faculty, journal editors, and the public. Representatives of the 3 chiropractic pediatric organizations were invited, with 2 accepting the invitation.

Systematic Review

We updated the literature considered in the original consensus document by conducting a systematic review of the literature published since publication of the original project. Thus, the updated review, which was conducted April–June 2015, included literature from January 2009 through March 2015. Our primary search question was,“What is the effectiveness of chiropractic care, including spinal manipulation, for conditions

experienced by children (<18 years of age)?”A secondary search question was,

“What are the adverse events associated with chiropractic care including spinal manipulation

among children (<18 years of age)?”These were the same search questions used in our previous project.

Figure 1

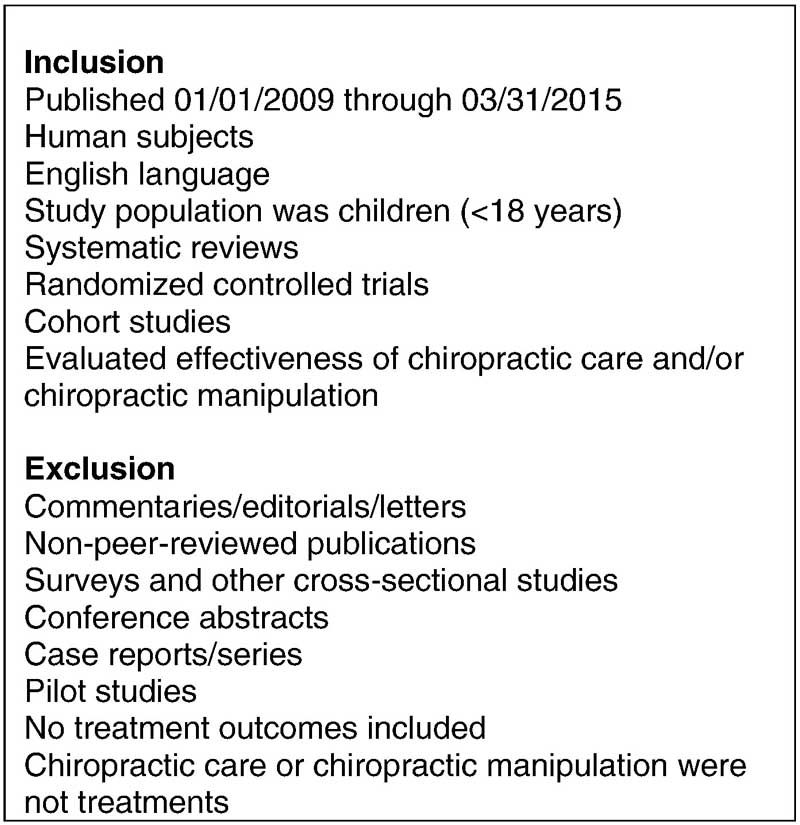

Figure 2 The specific inclusion and exclusion criteria for retaining articles are shown in Figure 1. The previous project included a literature review but not a systematic review, so it did not have specifically defined eligibility criteria. The eligibility criteria were applied to articles with an efficacy or effectiveness design only. For articles on adverse events, we included all studies regardless of design.

Search Strategy

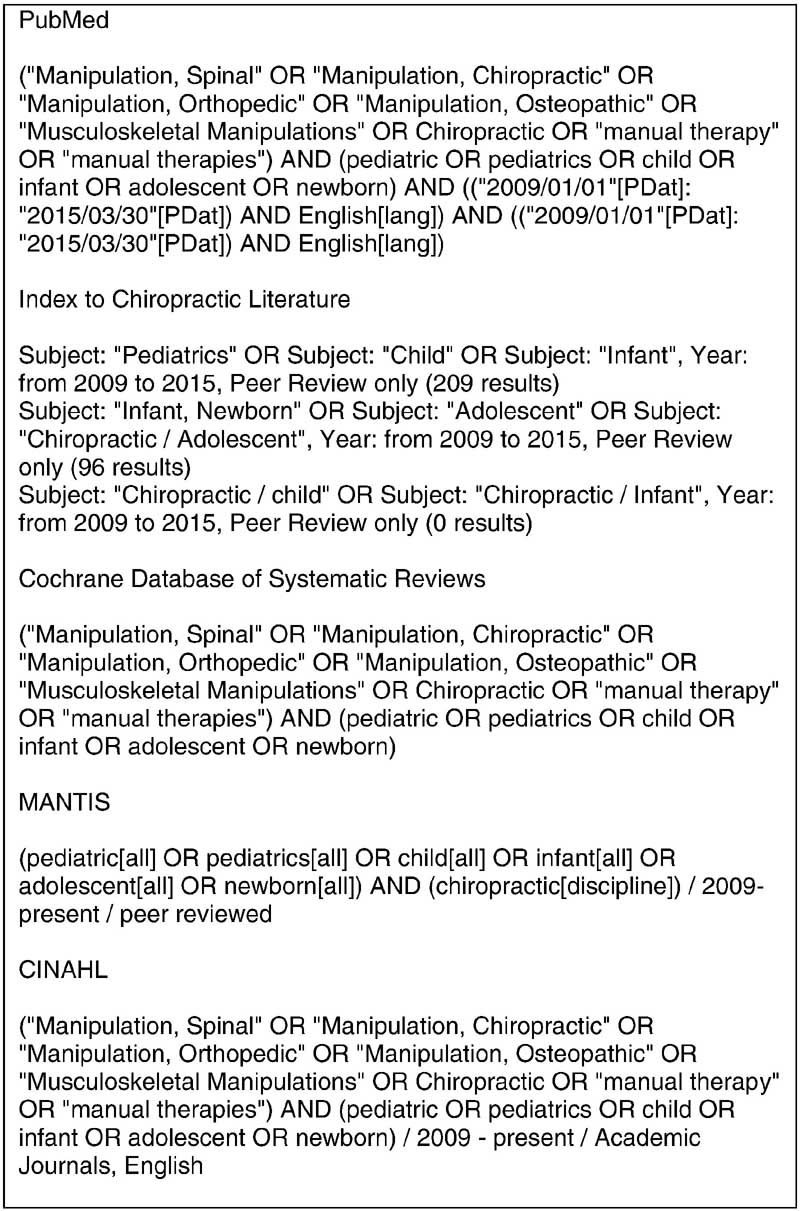

The following databases were included in the search: PubMed, Index to Chiropractic Literature, CINAHL, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and MANTIS. Details of the keyword search strategy for each database are provided in Figure 2. Articles and abstracts were screened independently by 2 reviewers. Data were not further extracted; summaries were created for the Delphi panelists.

Evaluation of Articles

For articles on effectiveness, we evaluated systematic reviews using the AMSTAR checklist, [20, 21] randomized controlled trials (RCTs) using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in RCTs, [22] and cohort studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale. [23] We evaluated the articles based on quality criteria used by Bronfort et al [24] and Clar et al [25] in their evaluation of the evidence for manual therapies (eg, study quality, consistency among different studies, number of studies, sample size, risk of bias). “No support” indicated insufficient evidence; “limited support” indicated a small number of studies of mixed quality with positive findings; “effective” indicated a number of studies with at least some of high quality with positive findings. For articles on adverse events, we did not evaluate articles for quality but instead summarized their content.

Seed Documents and Seed Statements

The seed statements were taken from the previous set of recommendations verbatim. [16] This seed document consisted of 49 seed statements relating to all of the important aspects of the clinical encounter. Other seed documents were developed from the results of the literature review:(1) a summary of the effectiveness of chiropractic care for children and

(2) a summary of the safety of chiropractic care for children.

Delphi Consensus Process

The consensus process was conducted by e-mail using a Delphi panel of experts. This process was economical and reduced the possibilities of panelists influencing one another’s ratings. All panelists were anonymous during the process.

As in our previous project, we used a modified RAND Corporation/University of California, Los Angeles, consensus methodology. [26] In this process, we asked panelists to rate the appropriateness of each seed statement. “Appropriateness” is that the expected health benefit is greater to the patient than any expected negative consequences, excluding cost concerns. [26] The panelists rated each statement using an ordinal scale of 1 to 9, ranging from “highly inappropriate” to “highly appropriate.” Scores in the range from 1 to 3 were anchored by the words “highly inappropriate,” scores from 4 to 6 were anchored by the word “uncertain,” and scores from 7 to 9 were anchored by the words “highly appropriate.” We required panelists to provide a specific reason for “inappropriate” ratings including a citation from refereed literature, if possible, to facilitate revision of the statement.

Responses were analyzed by entering the ratings into an SPSS (v. 20) database, whereas the verbatim comments were entered anonymously into a Word table. Analysis consisted of calculating 80% agreement on each statement. Consensus agreement on appropriateness was reached if a minimum of 80% of panelists rated a statement 7, 8, or 9 and the median response score was at least 7. Statements on which consensus was not reached were revised as per the comments and recirculated until consensus was reached. That is, consensus was only considered to have been reached if at least 80% of respondents rated a given statement as 7, 8, or 9. “Uncertain” ratings of 4, 5, or 6 indicated to us that the statement was unclear and so required revision for clarity. “Disagree” ratings of 1, 2, or 3 clearly indicated disagreement, and so the statement was revised by incorporating the panelists’ comments into a revised statement.

Delphi Panel

Panelists who served on the original project were invited to join the current project, with 12 accepting; 1 person who was previously on the Delphi panel moved to the Steering Committee. Additional panelists were nominated by the Steering Committee members to represent chiropractic college faculty and international experts in chiropractic pediatrics. [17]

The Delphi panel consisted of 29 experts from 5 countries (US = 18, Canada = 5, UK = 3, Denmark = 2, Netherlands = 1) and 10 US states (3 each from IA, MN, and OR; 2 each from MO and NY; 1 each from CA, IL, NJ, OH, and VA). The mean number of years in practice for our panelists was 20 years. Four DCs were cross-trained in another profession and held dual licenses: 2 DCs with RN degrees, 1 DC with an LMT degree, and 1 DC with a PT degree. Ten panel members had additional advanced academic degrees; 6 had a Masters’ degree, and 4 had a PhD degree.

Conduct of Consensus Process

After responses were analyzed as described above, the Steering Committee revised those statements that did not reach 80% consensus. If ratings indicated that panelists were uncertain (ratings 4–6), the statement was revised for clarity based on the panelists’ comments. If ratings indicated disagreement (ratings 1–3), the Steering Committee revised the statement to incorporate the panelists’ comments. The revised statements were then recirculated and rated again, until consensus was reached.

Results

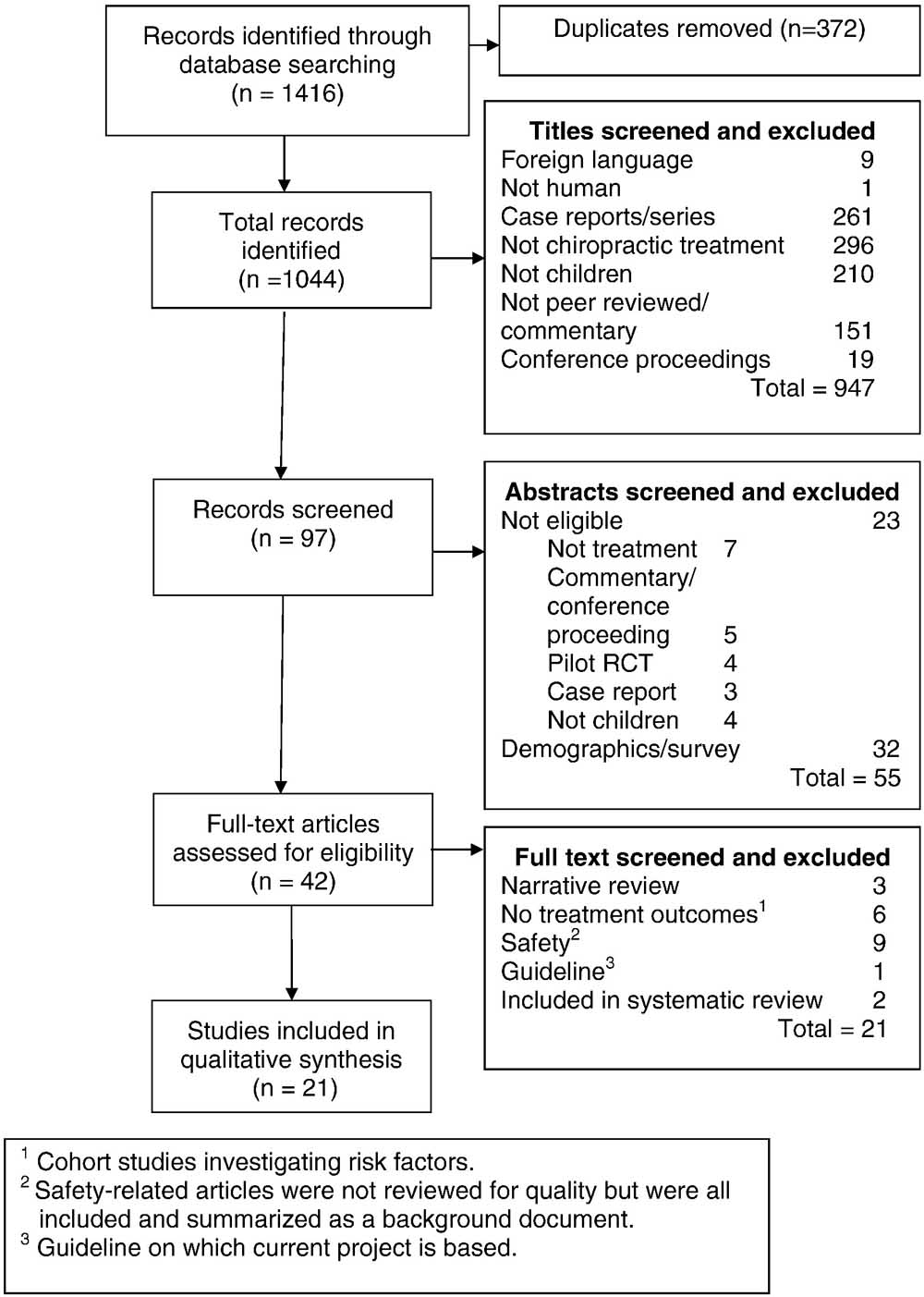

Figure 3

Table 1 Results of the Literature Review

Figure 3 provides a flow diagram of the literature search. The final result was that 21 full-text articles on effectiveness were retained, rated for quality, and included in the qualitative synthesis. Table 1 lists the studies related to effectiveness, indicating their author, research design, condition addressed, quality rating, and level of support for effectiveness of chiropractic for the condition addressed.There were only 3 RCTs from the total of 21 studies included, and all were for different conditions. [27–29]

Overall, limited support was found in high-quality studies for

asthma, [14, 30–32]

infantile colic, [14, 28, 33–35]

nocturnal enuresis, [14, 36] and

respiratory disease. [32]Nine articles on safety were included and summarized as background literature but were not formally reviewed for quality. [47–55]

Safety and Adverse Events

The 9 articles on safety were as follows:1 expert opinion, [47]

2 case reports, [48, 49]

1 “best evidence topic,” [50]

3 narrative reviews, [51–53] and

2 systematic reviews. [54, 55]The 2014 systematic review summarizes this topic as follows:

“Published cases of serious adverse events in infants and children receiving chiropractic, osteopathic, physiotherapy, or manual medical therapy are rare … no deaths associated with chiropractic care were found in the literature to date. Because underlying preexisting pathology was associated in a majority of reported cases, performing a thorough history and examination to exclude anatomical or neurologic anomalies before applying any manual therapy may further reduce adverse events across all manual therapy professions.” [54]

Results of the Consensus Process

Only 2 statements did not reach consensus on the first round. They were revised by the steering committee based on the panelists’ comments, and revised statements reached consensus in a second round. These are the statements which were revised:(1) “Vital signs should be assessed in an age appropriate manner as part of the initial examination and for purposes of reassessment at intervals determined by the patient’s clinical presentation.” The previous version had specified which vital signs should be measured depending on age, and the panel felt that this was unnecessarily specific.

(2) This statement, which was originally present, was decided by the panel to be dropped because of it being redundant based on the preceding statement cited: “For infants, vital signs should include all of these plus head circumference and fontanelle diameter.”The following text constitutes the results of the consensus process, representing the best practices document for chiropractic care for children.

Best Practices for Chiropractic Care for Children

Introduction

The purpose of this document is to protect the health of the public by defining the parameters of an appropriate approach to chiropractic care for children under 18 years of age. The potential benefits of any health care intervention should be weighed against the associated risks and the costs in terms of time and money. There are significant anatomical, physiological, developmental, and psychological differences between children and adults that may affect the appropriateness of any given health care intervention.

General Clinical Principles in the Care of Children

A child’s neuromusculoskeletal structure and function are less rigid and more flexible than those of an adult. Physical, psychological, and emotional responses to intervention vary.

Regarding patient communication:

Extracting relevant clinical information during the case history of a child patient requires special communication skills and experience.

Age-appropriate communication is necessary to help a child patient actively engage in the clinical encounter.

Infants and toddlers cannot communicate verbally, and therefore, the clinical encounter requires communication with a parent or legal guardian.

Regarding informed consent:

Informed consent signed by the child’s parent or legal guardian is required before initiating a clinical encounter with a child, including the initial consultation, performing an examination and diagnostic tests, and initiating a management program.

The DC should explain all procedures clearly and simply, and answer both the parent’s and child’s questions, to ensure that they can make an informed decision about their health care choices.

Verbal consent should be obtained from the child whenever developmentally appropriate.

The diagnosis should be explained to the parent/guardian (and the older child) in an age-appropriate, understandable manner.

The proposed treatment plan and any possible risks of care should be explained along with all other reasonable treatment options.

Chiropractic Management of Pediatric Patients

Chiropractic management of the child should follow the 3 basic principles of evidence-based practice, which are to make clinical judgments based on the use of(1) the best available evidence combined with

(2) the clinician’s experience and

(3) the patient’s preferences.

The research community has just begun to investigate the effectiveness of chiropractic care for many pediatric conditions; however, lack of research evidence does not imply ineffectiveness. Evidence-based practice is the integration of clinical expertise and patient values with the best available research evidence. [56] A therapeutic trial of chiropractic care can be a reasonable approach to management of the pediatric patient in the absence of conclusive research evidence when clinical experience and patient/parent preferences are aligned. There are 3 basic chiropractic management approaches to the care of the child patient:(1) sole management by a chiropractic physician,

(2) comanagement with other appropriate health care providers, and

(3) referral to another licensed or certified health care provider/specialist.Comanagement with other appropriate health care providers is appropriate under many conditions including the following circumstances noted below:

The child patient is not showing clinically significant improvement after an initial trial of chiropractic care.

The parents of the child patient request such a comanagement approach.

There are significant comorbidities that are outside the scope of chiropractic practice or require medication, advanced diagnostic imaging, or laboratory studies.

When the DC orders diagnostic imaging or laboratory studies, copies of these results should be forwarded to the child’s primary care physician for coordination of care.

Management of many nonmusculoskeletal conditions may benefit from comanagement with the child’s primary care physician and/or other providers, depending on the condition.

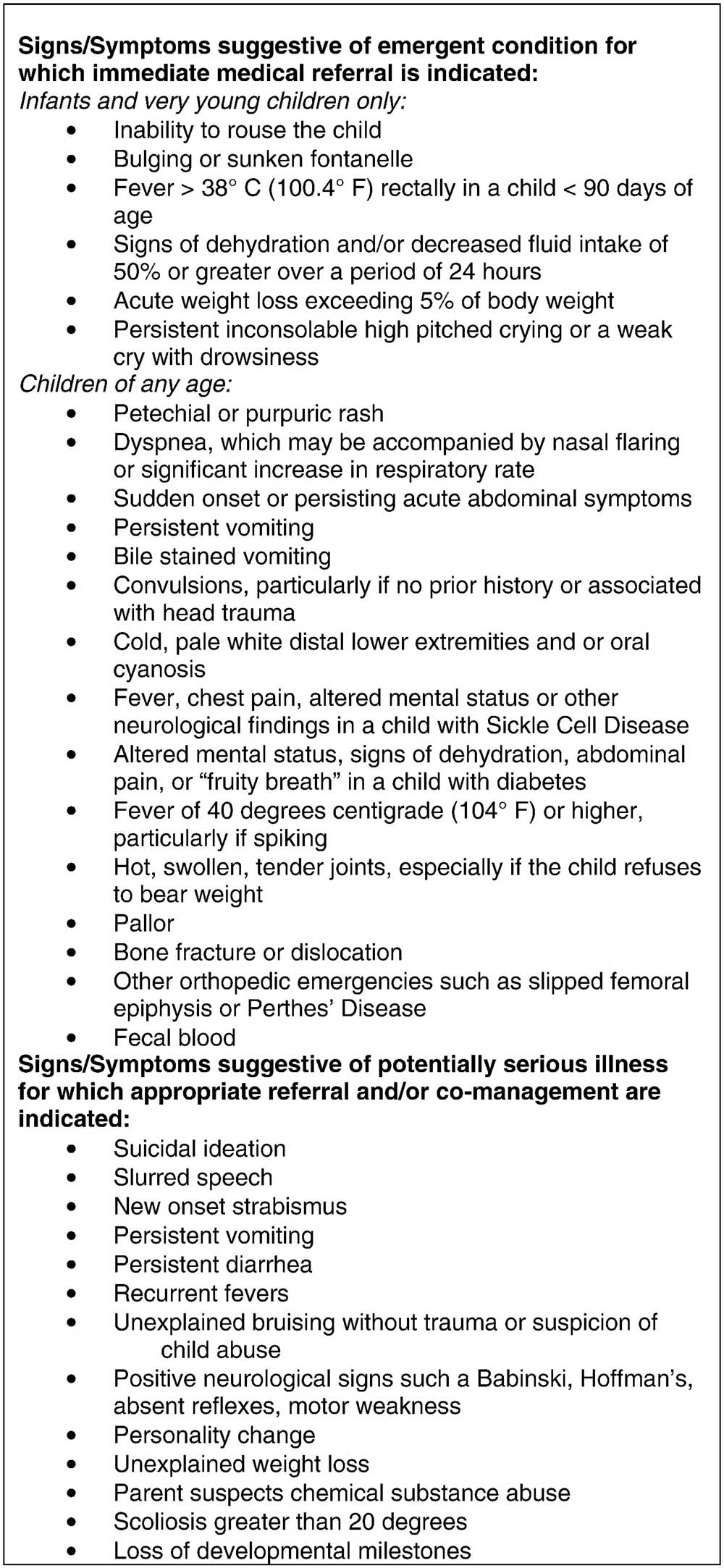

Immediate referral to a medical specialist should occur when the case history and examination reveal any “red flags” suggestive of serious pathology.

Figure 4 A list of these red flags is provided in Figure 4.

Clinical History

A focused case history should be conducted at the initial visit. The comprehensive case history at the initial visit should include a review of systems, developmental milestones, family history, health care history, concurrent health care, and medication use. Information on health habits, including breastfeeding, diet, sleep, physical activity, and injuries, should be included. For very young children, a review of relevant prenatal events, including the health of the mother, as well as a review of the birth history (eg, gestational age, birth weight, perinatal complications), is appropriate. Obtaining case history information from the child can be helpful in determining the appropriate case management.

Red Flags in Pediatric Patients

If the history and/or examination reveal “red flags” indicating serious conditions, the child should be referred to an appropriate provider for further diagnosis and/or care (see Fig 4 for list of red flags).

Examination

Clinically relevant and valid examination procedures should be used to enable the practitioner to move from a working diagnosis, which is based on the history, to a short list of differential diagnoses. Necessary diagnostic or examination procedures outside the practitioner’s scope of practice or range of experience should be referred to an appropriately qualified and experienced health professional. Vital signs should be assessed in an age-appropriate manner as part of the initial examination and for purposes of reassessment at intervals determined by the patient’s clinical presentation.

An age-appropriate neurodevelopmental examination should be conducted. Neurological tests include balance and gait, neurodevelopmental age-appropriate milestones, cranial nerve examination, and pathological reflexes. Primitive reflexes in the infant should be assessed.

Diagnostic Imaging

Clinical indications for radiographic examination of the pediatric patient are history of trauma, suspicion of serious pathology, and/or assessment of scoliosis. The routine or repeated use of radiographs of the child patient is not recommended without clear clinical justification. Plain film radiographs may be indicated in cases of clinically suspected trauma-induced injury, such as fracture or dislocation. Radiographs may also be indicated in cases of clinically suspected orthopedic conditions such as hip disorders or pathology, such as bone malignancy. Plain film radiographs may be necessary for determination of contraindications to manipulation, for example, congenital or genetic conditions that may cause compromise of the spine, spinal cord, or extremities. There are limitations to the diagnostic utility of plain film radiograph and/or diagnostic ultrasonography for the diagnosis of certain pediatric or adolescent conditions, which may require the use of more advanced diagnostic imaging such as magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, or bone scan.

Considerations for Treating Children With Manual Procedures

Patient size: Biomechanical force should be modified in proportion to the size of the child.

Structural development: Manual procedures should be modified to accommodate the developing skeleton.

Flexibility of joints: Manual procedures should take into account the greater flexibility and lesser muscle mass of children, using gentler and lighter forces.

Patient preferences: The clinician should adapt manipulation and soft tissue techniques and procedures that support the needs and comfort of the child.

Pediatric Care Planning

Well child visits are an established aspect of pediatric health care and may be indicated for the purpose of health promotion counseling and clinical assessment of asymptomatic pediatric patients. Doctors of chiropractic should emphasize disease prevention and health promotion through counseling on physical activity, nutrition, injury prevention, and a generally healthy lifestyle. Although immunization is a well-established medical approach to disease prevention, DCs may be asked for information about immunizations by a child’s parents. Doctors of chiropractic should provide balanced, evidence-based information from credible resources and/or refer the parents to such resources. Doctors of chiropractic should counsel children and their parents in healthy behavior and lifestyle, including but not limited to the following topics: adequate age-appropriate physical activity and decreased screen time, such as TV, electronic games, and computer use; healthy diet; adequate sleep; injury prevention; and substance use (eg, caffeinated beverages, alcohol, tobacco, steroids, and other drugs).

Public Screening of Children for Health Problems

Any tests or procedures used for public screenings should be based on recognized evidence of their benefit for disease prevention and health promotion.

Discussion

Although this consensus document is based mostly upon expert opinion, our panel members were informed from evidence obtained from an updated and current systematic review of the literature. This review included a search for studies reporting adverse events associated with chiropractic treatment of child patients. As with our previous consensus process, we compiled an interprofessional group consisting of panel members and representatives from 2 of the 3 major chiropractic pediatric organizations.

These best practices guidelines represent an important synthesis of the best currently available evidence from the literature combined with the collective opinion of a panel of content experts. This information contained in this publication may impact several levels of stakeholders, including practicing DCs who treat children, their patients and parents, other health care providers, third-party payers, and the general public.

Practicing DCs may refer to this best practices document to assist them with the general chiropractic consensus about the skills considered necessary to appropriately manage pediatric patients who present to them for diagnosis and treatment. This information could also serve as a framework for DCs who wish to acquire additional knowledge needed to appropriately care for the pediatric population in the form of advanced training or continuing education coursework.

Parents who bring their children to DCs for treatment will also be able to refer to this document as a means by which to inform them about the appropriateness of the level of chiropractic care their child is receiving. It will allow parents to more accurately identify those DCs who appear to be practicing within the generally acceptable norms of best chiropractic practice for the management of children.

Other health care providers such as nurses, physician assistants, and pediatricians are often comanaging children who are under chiropractic care. These health care professionals often are in the dark regarding what constitutes “reasonable chiropractic management” of the child patient. This document can help enlighten them by providing a better understanding of the nature, scope, and expectations of the pediatric DC encounter and thereby provide a foundation of understanding for mutual referral and collaboration.

Health insurers and third-party payers are increasingly looking for evidence to inform decisions about their medical policy and benefit limits. Often lacking in this process are the resources and skills need to synthesize the scientific literature and to gather input from the providers most affected by their policy decisions. This document will assist policy makers by providing an evidence synthesis (from the systematic review) and consensus opinion about important aspects of chiropractic management/treatment of the child patient. Many of the clinically appropriate responsibilities for chiropractic management of the child patient are outlined in this document, which should assist policy makers in formulating more reasonable parameters about medical necessity and appropriateness of chiropractic care for children.

Lastly, the general public and media have often viewed chiropractic treatment of children as somewhat outside of the norms of general health care practice. This document provides publically available information about a rational, reasonable, and best practices approach to pediatric chiropractic care. Parents are often accessing health care databases and using the Internet to find information to help them make decisions about what type of treatment and provider to access for their children. This consensus document will provide them with a source of credible, scientific, and evidence-based information upon which to make more informed decisions about the choice of chiropractic care as a reasonable health care option for children.

Limitations

Because of the substantial gaps in the evidence for the effectiveness of chiropractic care for conditions experienced by children, it was important to develop a set of recommendations that were evidence informed yet the result of expert opinion achieved through a rigorous consensus process. However, the gaps in the evidence base still represent a limitation to these recommendations because expert consensus is a lower form of evidence to be relied on principally when higher levels of evidence are lacking. In addition, our recommendations primarily deal with examination and manual care and do not cover other services that DCs may provide to children.

Another limitation of a study based on consensus is that it is possible that the panelists do not represent the general population of subject experts. In addition, we did not have laypeople/parents represented on the panel, although we did have such representation on the Steering Committee, so we feel that compensated for this limitation to some degree. Lastly, we did not seek any formal input from organizational stakeholders that represent third-party payers, legislative bodies, or nonchiropractic pediatric organizations. We did not provide any specific recommendations about age-appropriate treatment dosage, frequency, and duration, which were beyond the scope of this project.

Conclusion

All of the seed statements in this document were approved through consensus at a level of 80% agreement or higher. This best practices document represents a general framework for what constitutes an evidence-based and reasonable approach to the chiropractic management of infants, children, and adolescents.

Practical Applications

The original best practices recommendations were updated

by a multidisciplinary panel.These recommendations provide an evidence-based framework

for the chiropractic management of infants, children, and adolescents.This is a living document that should be periodically updated

to remain current as new evidence emerges.

Funding Sources and Potential Conflicts of Interest

This project was funded by a grant from the NCMIC Foundation. All Delphi panelists and Steering Committee members served without compensation. No conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

Contributorship Information

Concept development (provided idea for the research): C.H., M.S.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): C.H., M.S.

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript): C.H., M.S., S.V., E.H.

Data collection/processing (responsible for experiments, patient management, organization, or reporting data): C.H.

Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results): C.H., M.S., S.V., E.H.

Literature search (performed the literature search): C.H., M.S.

Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): C.H., M.S., S.V.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking): C.H., M.S., S.V.,E.H.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Michelle Anderson, Project Coordinator, for managing the complex communications required in this project. We thank Sheryl Walter, MLS, who conducted the literature search. A number of experts generously donated their time and expertise. Members of the Steering Committee included Randy Ferrance, DC, MD; Stephen Lazoritz, MD; Sharon Vallone, DC; Elise Hewitt, DC; Stephanie O’Neill-Bhogal, DC; and John Weeks.

The Delphi panelists included Laura Baffes, DC; Anna Bender, DC; Linda J. Bowers, DC; Jennifer Brocker, DC; Maria Browning, DC, MSc; Jerrilyn Cambron, DC, PhD; Christina Cunliffe, DC, PhD; Matthew Doyle, MSc AP; Ronald J. Farabaugh, DC; Maggie Finn, DC, MA; Pamela S. Gindl, DC; Brian Gleberzon, DC, MHSc; Paul J. Greteman, DC; Julie Hartman, DC, MS; Jan Hartvigsen, DC, PhD; Navine Haworth, DC, PhD (c); Sue Weber Hellstenius, DC, MSc; Lise Hestbaek, DC, PhD; Randy L. Hewitt, DC; Simone Knaap, DC, MSc; Anne Langford, DC; Deborah Lindeman, RN, DC; Michael Master, DC; Katherine Pohlman, DC, MS, PhD (c); Anne Spicer, DC; Kasey Sudkamp, DPT; Mary Unger-Boyd, DC; Meghan Van Loon, PT, DC; and Stephen A. Zylich, DC.

References:

Vallone, SA, Miller, J, Larsdotter, A, and Barham-Floreani, J.

Chiropractic Approach to the Management of Children

Chiropractic & Osteopathy 2010 (Jun 2); 18: 16Black, LI, Clarke, TC, Barnes, PM, Stussman, BJ, and Nahin, RL.

Use of Complementary Health Approaches Among Children Aged

4–17 Years in the United States: National Health

Interview Survey, 2007–2012

National Health Statistics Report 2015 (Feb 10); (78): 1–19Weeks, WB, Goertz, CM, Meeker, WC, and Marchiori, DM.

Public perceptions of doctors of chiropractic: results of a national survey

and examination of variation according to respondents' likelihood to use

chiropractic, experience with chiropractic, and chiropractic supply

in local health care markets.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015; 38: 533–544Davis, MA, West, AN, Weeks, WB, and Sirovich, BE.

Health behaviors and utilization among users of complementary and

alternative medicine for treatment versus health promotion.

Health Serv Res. 2011; 46: 1402–1416Hestbaek L, Jørgensen A, Hartvigsen J.

A Description of Children and Adolescents in Danish Chiropractic Practice:

Results from a Nationwide Survey

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 (Oct); 32 (8): 607–615Hestbaek, L and Stochkendahl, MJ.

The Evidence Base for Chiropractic Treatment of Musculoskeletal

Conditions in Children and Adolescents: The Emperor's New Suit?

Chiropractic & Osteopathy 2010 (Jun 2); 18: 15Marchand, AM.

Chiropractic Care of Children from Birth to Adolescence and Classification of

Reported Conditions: An Internet Cross-Sectional Survey of 956 European Chiropractors

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012 (Jun); 35 (5): 372–380Alcantara, J, Ohm, J, and Kunz, D.

The Safety and Effectiveness of Pediatric Chiropractic: A Survey of

Chiropractors and Parents in a Practice-based Research Network

Explore (NY) 2009 (Sep–Oct); 5 (5): 290–295Ndetan, H, Evans, MW, Hawk, C, and Walker, C.

Chiropractic or Osteopathic Manipulation for Children in the United States:

An Analysis of Data from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey

J Altern Complement Med. 2012 (Apr); 18 (4): 347–353Adams, J, Sibbritt, D, Broom, A et al.

Complementary and alternative medicine consultations in urban and

nonurban areas: a national survey of 1427 Australian women.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2013; 36: 12–19Adams, D, Dagenais, S, Clifford, T et al.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use by Pediatric Specialty Outpatients

Pediatrics. 2013 (Feb); 131 (2): 225–232April, KT, Feldman, DE, Zunzunegui, MV, Descarreaux, M, and Grilli, L.

Complementary and alternative health care use in young children with

physical disabilities waiting for rehabilitation services in Canada.

Disabil Rehabil. 2009; 31: 2111–2117Ferrance, RJ and Miller, J.

Chiropractic Diagnosis and Management of Non-musculoskeletal Conditions

in Children and Adolescents

Chiropractic & Osteopathy 2010 (Jun 2); 18: 14Gleberzon, BJ, Arts, J, Mei, A, and McManus, EL.

The Use of Spinal Manipulative Therapy For Pediatric Health Conditions:

A Systematic Review of the Literature

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2012 (Jun); 56 (2): 128–141Gotlib, A and Rupert, R.

Chiropractic Manipulation in Pediatric Health Conditions - An Updated Systematic Review

Chiropractic & Osteopathy 2008 (Sep 12); 16: 11Hawk, C, Schneider, M, Ferrance, RJ, Hewitt, E, Van Loon, M, and Tanis, L.

Best Practices Recommendations for Chiropractic Care for Infants, Children,

and Adolescents: Results of a Consensus Process

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 (Oct); 32 (8): 639–647Becker, M, Neugebauer, EA, and Eikermann, M.

Partial updating of clinical practice guidelines often makes more sense

than full updating: a systematic review on methods and the development of an updating procedure.

J Clin Epidemiol. 2014; 67: 33–45Shekelle, P, Woolf, S, Grimshaw, JM, Schunemann, HJ, and Eccles, MP.

Developing Clinical Practice Guidelines: Reviewing, Reporting, and Publishing Guidelines;

Updating Guidelines; and the Emerging Issues of Enhancing Guideline Implementability

and Accounting for Comorbid Conditions in Guideline Development

Implementation Science 2012 (Jul 4); 7: 62Pohlman, KA, Hondras, MA, Long, CR, and Haan, AG.

Practice Patterns of Doctors of Chiropractic With

a Pediatric Diplomate: A Cross-sectional Survey

BMC Complement Altern Med. 2010 (Jun 14); 10: 26Shea, BJ, Grimshaw, JM, Wells, GA et al.

Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological

quality of systematic reviews.

BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007; 7: 10Shea, BJ, Bouter, LM, Peterson, J et al.

External validation of a measurement tool to assess systematic reviews (AMSTAR).

PLoS One. 2007; 2: e1350Higgins, JP, Altman, DG, Gotzsche, PC et al.

The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials.

BMJ. 2011; 343: d5928Wells, GA, Shea, B, Higgins, JP, Sterne, J, Tugwell, P, and Reeves, BC.

Checklists of methodological issues for review authors to consider when

including non-randomized studies in systematic reviews.

Res Synth Methods. 2013; 4: 63–77Bronfort G, Haas M, Evans R, Leiniger B, Triano J.

Effectiveness of Manual Therapies: The UK Evidence Report

Chiropractic & Osteopathy 2010 (Feb 25); 18 (1): 3Clar C, Tsertsvadze A, Court R, Hundt G, Clarke A, Sutcliffe P.

Clinical Effectiveness of Manual Therapy for the Management of

Musculoskeletal and Non-Musculoskeletal Conditions:

Systematic Review and Update of UK Evidence Report

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2014 (Mar 28); 22 (1): 12Fitch, K, Bernstein, SJ, Aquilar, MS et al.

The RAND UCLA appropriateness method user's manual.

RAND Corp., Santa Monica, CA; 2003Cerritelli, F, Pizzolorusso, G, Ciardelli, F et al.

Neonatology and Osteopathy (NEO) study: effect of OMT on preterms' length of stay.

BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012; 12: O36Miller J, Newell D, Bolton J.

Efficacy of Chiropractic Manual Therapy on Infant Colic:

A Pragmatic Single-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012 (Oct); 35 (8): 600–607Wyatt, K, Edwards, V, Franck, L et al.

Cranial osteopathy for children with cerebral palsy: a randomised controlled trial.

Arch Dis Child. 2011; 96: 505–512George, M and Topaz, M.

A Systematic review of complementary and alternative medicine

for asthma self-management.

Nurs Clin North Am. 2013; 48: 53–149Alcantara, J, Alcantara, JD, and Alcantara, J.

The Chiropractic Care of Patients with Asthma:

A Systematic Review of the Literature to Inform Clinical Practice

Clinical Chiropractic 2012 (Mar); 15 (1): 23–30Pepino, VC, Ribeiro, JD, de Oliveira Ribeiro, MA,

de Noronha, M, Mezzacappa, MA, and Schivinski, CI.

Manual therapy for childhood respiratory disease: a systematic review.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2013; 36: 57–65Alcantara JD, Alcantara J.

The Chiropractic Care of Infants With Colic: A Systematic Review of the Literature

Explore (NY). 2011 (May); 7 (3): 168–174Ernst, E.

Chiropractic spinal manipulation for infant colic: a systematic review

of randomised clinical trials.

Int J Clin Pract. 2009; 63: 1351–1353Dobson D, Lucassen PLBJ, Miller JJ, Vlieger AM, Prescott P, Lewith G.

Manipulative Therapies for Infantile Colic

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 (Dec 12); 12: CD004796Huang, T, Shu, X, Huang, YS, and Cheuk, DK.

Complementary and miscellaneous interventions for nocturnal enuresis in children.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011; : Cd005230Karpouzis, F, Bonello, R, and Pollard, H.

Chiropractic Care for Pediatric and Adolescent Attention-Deficit/

Hyperactivity Disorder: A Systematic Review

Chiropractic & Osteopathy 2010 (Jun 2); 18: 13Plaszewski, M and Bettany-Saltikov, J.

Non-surgical interventions for adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis: an overview of systematic reviews.

PLoS One. 2014; 9: e110254Alcantara, J, Alcantara, JD, and Alcantara, J.

A Systematic Review of the Literature on the Chiropractic Care

of Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Explore (NY). 2011 (Nov); 7 (6): 384–390Poder, TG and Lemieux, R.

How effective are spiritual care and body manipulation therapies in

pediatric oncology? A systematic review of the literature.

Glob J Health Sci. 2014; 6: 112–127Chase, J and Shields, N.

A systematic review of the efficacy of non-pharmacological, non-surgical

and non-behavioural treatments of functional chronic constipation in children.

Aust N Z Continence J. 2011; 17: 40–50Alcantara, J, Alcantara, JD, and Alcantara, J.

An integrative review of the literature on the chiropractic care

of infants with constipation.

Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2014; 20: 32–36Schetzek, S, Heinen, F, Kruse, S et al.

Headache in children: update on complementary treatments.

Neuropediatrics. 2013; 44: 25–33Vaughn, DW, Kenyon, LK, Sobeck, CM, and Smith, RE.

Spinal manual therapy interventions for pediatric patients:

a systematic review.

J Man Manipulative Ther. 2012; 20: 153–159Posadzki, P and Ernst, E.

Is spinal manipulation effective for paediatric conditions?

An overview of systematic reviews.

Focus Altern Complement Ther. 2012; 17: 22–26Pohlman KA, Holton-Brown MS.

Otitis Media and Spinal Manipulative Therapy: A Literature Review

Journal of Chiropractic Medicine 2012 (Sep); 11 (3): 160–169Gilmour, J, Harrison, C, Asadi, L, Cohen, MH, and Vohra, S.

Complementary and alternative medicine practitioners' standard of care:

responsibilities to patients and parents.

Pediatrics. 2011; 128: S200–S205Deputy, SR.

Arm weakness in a child following chiropractor manipulation of the neck.

Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2014; 21: 124–126Wilson, PM, Greiner, MV, and Duma, EM.

Posterior rib fractures in a young infant who received chiropractic care.

Pediatrics. 2012; 130: e1359–e1362Doyle, MF.

Is chiropractic paediatric care safe? A best evidence topic.

Clin Chiropr. 2011; 14: 97–105Marchand, AM.

A Literature Review of Pediatric Spinal Manipulation and Chiropractic

Manipulative Therapy: Evaluation of Consistent Use of Safety Terminology

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015 (Nov); 38 (9): 692–698Marchand AM.

A Proposed Model With Possible Implications for Safety and Technique Adaptations

for Chiropractic Spinal Manipulative Therapy for Infants and Children

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2015 (Nov); 38 (9): 713–726Miller, JE.

Safety of Chiropractic Manual Therapy for Children:

How Are We Doing?

J Clinical Chiropractic Pediatrics 2009 (Dec); 10 (2): 655–660Todd, AJ, Carroll, MT, Robinson, A, and Mitchell, EK.

Adverse Events Due to Chiropractic and Other Manual Therapies for Infants

and Children: A Review of the Literature

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015 (Nov); 38 (9): 699–712Humphreys, BK.

Possible Adverse Events in Children Treated By Manual Therapy: A Review

Chiropractic & Osteopathy 2010 (Jun 2); 18: ; 12Sackett, DL, Rosenberg, WM, Gray, JA, Haynes, RB, and Richardson, WS.

Evidence-Based Medicine: What It Is and What It Isn't

British Medical Journal 1996 (Jan 13); 312 (7023): 71–72

Return to PEDIATRICS

Return to BEST PRACTICES

Return to PEDIATRICS GUIDELINES

Since 4–13–2016

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |