Does Cervical Spine Manipulation Reduce Pain in People

with Degenerative Cervical Radiculopathy?

A Systematic Review of the Evidence,

and a Meta-analysisThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Clinical Rehabilitation 2016 (Feb); 30 (2): 145-155 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Liguo Zhu, Xu Wei and Shangquan Wang

Department of Spine,

Wangjing Hospital,

Beijing, People's Republic of China.

OBJECTIVE: To access the effectiveness and safety of cervical spine manipulation for cervical radiculopathy.

DATA SOURCES: PubMed, the Cochrane Central Registry of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (CBM), Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chinese Scientific Journal Database (VIP), Wanfang data, the website of Chinese clinical trial registry and international clinical trial registry by US National Institutes of Health.

REVIEW METHODS: Randomized controlled trials that investigated the effects of cervical manipulation compared with no treatment, placebo or conventional therapies on pain measurement in patients with degenerative cervical radiculopathy were searched. Two authors independently evaluated the quality of the trials according to the risk of bias assessment provided by the PEDro (physiotherapy evidence database) scale. RevMan V.5.2.0 software was employed for data analysis. The GRADE approach was used to evaluate the overall quality of the evidence.

RESULTS: Three trials with 502 participants were included. Meta-analysis suggested that cervical spine manipulation (mean difference 1.28, 95% confidence interval 0.80 to 1.75; P < 0.00001; heterogeneity: Chi2 = 8.57, P = 0.01, I2 = 77%) improving visual analogue scale for pain showed superior immediate effects compared with cervical computer traction. The overall strength of evidence was judged to be moderate quality. One out of three trials reported the adverse events and none with a small sample size.

CONCLUSION: There was moderate level evidence to support the immediate effectiveness of cervical spine manipulation in treating people with cervical radiculopathy. The safety of cervical manipulation cannot be taken as an exact conclusion so far.

From the Full-Text Article:

Introduction

Degenerative cervical radiculopathy is a frequent impairment owing to compression of a cervical nerve root, a term used to describe neck pain associated with pain radiating into the arm (cervicobrachial pain). [1, 2] As the best known type of cervical spondylosis, cervical radiculopathy is often induced by osteophytosis, cervical interverbral disc herniation. In China, the prevalence of cervical spondylosis was 17.3%, and a high percentage of 60% to 70% of patients were occupied by cervical radiculopathy. [3, 4]

Treatment of cervical radiculopathy is often managed through conservative therapies, which includes oral analgesics, oral steroids, cervical computer traction, manual therapy, exercise, cervical collar and various combinations of these. [5, 6] But treatments are subject to some limitations owing to the quality of evidence and adverse drug reaction. In a comprehensive literature synthesis conducted by Task Force on Neck Pain and its Associated Disorders, the insufficient study evidence of noninvasive interventions for patients with radicular symptoms was available. [7] Oral non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs are generally used to alleviate severe pain. On the other hand, long-term nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs use may increase the risk and cause gastrointestinal ulcers, serious cardiovascular events, hypertension, acute renal failure and worsening of pre-existing heart failure. [8]

In the world, many patients with cervical radiculopathy are increasingly turning to specific conservative treatments, including cervical spine manipulation, to relieve their symptoms and reduce the side-effects of medications. [9–11] The action effects of cervical manipulative therapy have been found or validated in some experiments, such as separation of the facet joints, relaxation of paraspinal muscles, increasing of blood flow and so on. [12] As one of the complementary and alternative therapies, cervical spine manipulation has been used for several years in China. [13, 14] According to the definition provided in the literatures, cervical manipulation is described as the use of hands applied to the patients, thereafter a rapid highvelocity, low-amplitude thrust directed at the cervical joints, often accompanied by an audible crack. [15, 16] Additionally, light soft-tissue massage, which is used to facilitate treatment, is permitted before manipulation. [17] Cavitation should not be considered as an absolute indicator for successful thrust manipulation. [18, 19]

Recently, recommendation was made for the treatment of non-specific neck pain with spinal manipulation in a new evidence-based guideline. [20] However, there is relatively little evidence into the effectiveness and safety of cervical spine manipulation for specific neck pain, including cervical radiculopathy. The following questions were inconclusive:(1) the effectiveness of standalone intervention, cervical manipulation for neck pain with radiculopathy;

(2) the adverse effect of cervical manipulation.To date, although a number of systematic reviews included cervical spine manipulation for cervical radiculopathy, the reviews did not report results for cervical radiculopathy separately. [21–27] Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review is to evaluate the literature regarding the effectiveness and safety of using cervical spine manipulation in the treatment of cervical radiculopathy.

Methods

Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

All the parallel randomized controlled trials that compared cervical manipulation to no treatment or conventional therapy in patients with cervical radiculopathy were included. According to the definition of the North American Spine Society, cervical radiculopathy was defined as neck pain in a radicular pattern in one or both upper extremities related to compression and/or irritation of one or more cervical nerve roots. [28] Cervical spine manipulation referred to a “manual therapy technique comprising a continuum of skilled passive movements to the cervical joints and/or related soft tissues that are applied at varying speeds and amplitudes, including a small-amplitude/highvelocity therapeutic movement”. [29] In addition, randomized controlled trials that compared cervical manipulative therapy and existing conventional therapies with conventional therapies for cervical radiculopathy were included as well. The outcome measurement was validated with the visual analogue scale, numerical rating scales, McGill pain questionnaire on pain relief or analogous pain scales.

There were no restrictions on population characteristics and publication type. Languages of published or unpublished literatures were restricted in English and Chinese. Quasi-randomized controlled trials were not enrolled. Duplicated publications reporting the same groups of populations were excluded. Abstract for which full reports were not available and letters to the editor were also excluded.

Database and search strategies

The following literature sources were searched up to December 2014: PubMed (1966–2014), the Cochrane Central Registry of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library (Issue 12 of 12, December 2014), EMBASE (1980–2014), Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (CBM) (1978–2014), Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) (1989–2014), Chinese Scientific Journal Database (VIP) (1989–2014) and Wanfang data (1989–2014). All searches were completed on 25 December 2014. Registered clinical trials were conducted in the website of Chinese clinical trial registry (http://www.chictr.org) and international clinical trial registry by US National Institutes of Health (http://clinicaltrials.gov). The search terms and their combination were used: “radiculopathy”, “cervical radiculopathy”, “cervicobrachial pain”, “cervical spondylotic radiculopathy”, “cervical disc herniation”, “conservative treatment”, “conservative therapy”, “manual therapy”, “cervical spine manipulation”, “manipulati*”, “random”, “review”. Eligible studies were selected and checked independently by two authors (XW and SW).

Data extraction and methodological quality assessment

Two authors (XW and SW) conducted data extraction independently according to predefined criteria. The extracted data included the author names, year of publication, sample size, mean age and symptom duration, diagnosis criteria, type of manipulation, treatment process, details of the intervention and control, duration of the treatment and follow-up, outcome measurement and adverse effects for each study. Disagreement was resolved by discussion and reached consensus through a third party (LZ). If additional data was needed, we contacted the study authors in time.

The methodological quality of included randomized controlled trials was assessed independently using criteria from the PEDro (physiotherapy evidence database) scale (XW and SW). [30] The 11 items were evaluated in the PEDro scale. Each item was answered either “no” or “yes”. If a criterion was satisfied, a point would be awarded for that criterion, a zero otherwise. Owing to the eligibility criterion item not being included in the total score, the maximum value of the PEDro scale was 10. To determine an accepted cut-off point for this review, two systematic reviews by Maher [31] and Boyles et al. [22] were consulted. The PEDro scale total score of 5 was considered to be acceptable as the cut-off point, which indicated a low risk of bias.

Data synthesis

Dichotomous data were expressed as relative risk (RR) and continuous outcomes as mean difference (MD), both with 95% confidence interval (CI). The mean difference value between the end of the final intervention and the baseline was used to assess the difference between the groups. Heterogeneity was assessed using both the Chi-squared test and the I2 statistic with an I2 value greater than 50% indicative of substantial heterogeneity. We used Revman 5.2.0 software provided by Cochrane Collaboration for data analysis. [32]

Strength of evidence

We applied the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) approach to evaluate the overall quality of the evidence. [33] Five basic factors could decrease the quality of evidence:(1) Limitations in study design and/or execution;

(2) inconsistency of results;

(3) indirectness of evidence;

(4) imprecision of results;

(5) publication bias.There were also three factors for upgrading. [34] Two independent reviewers (XW and SW) assessed the quality of evidence. The quality of the evidence was downgraded by one level when one of the factors described above was met. The following grading of quality of evidence and definitions were used.

High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low quality: Any estimate of effect is very uncertain.

Results

Description of included trials

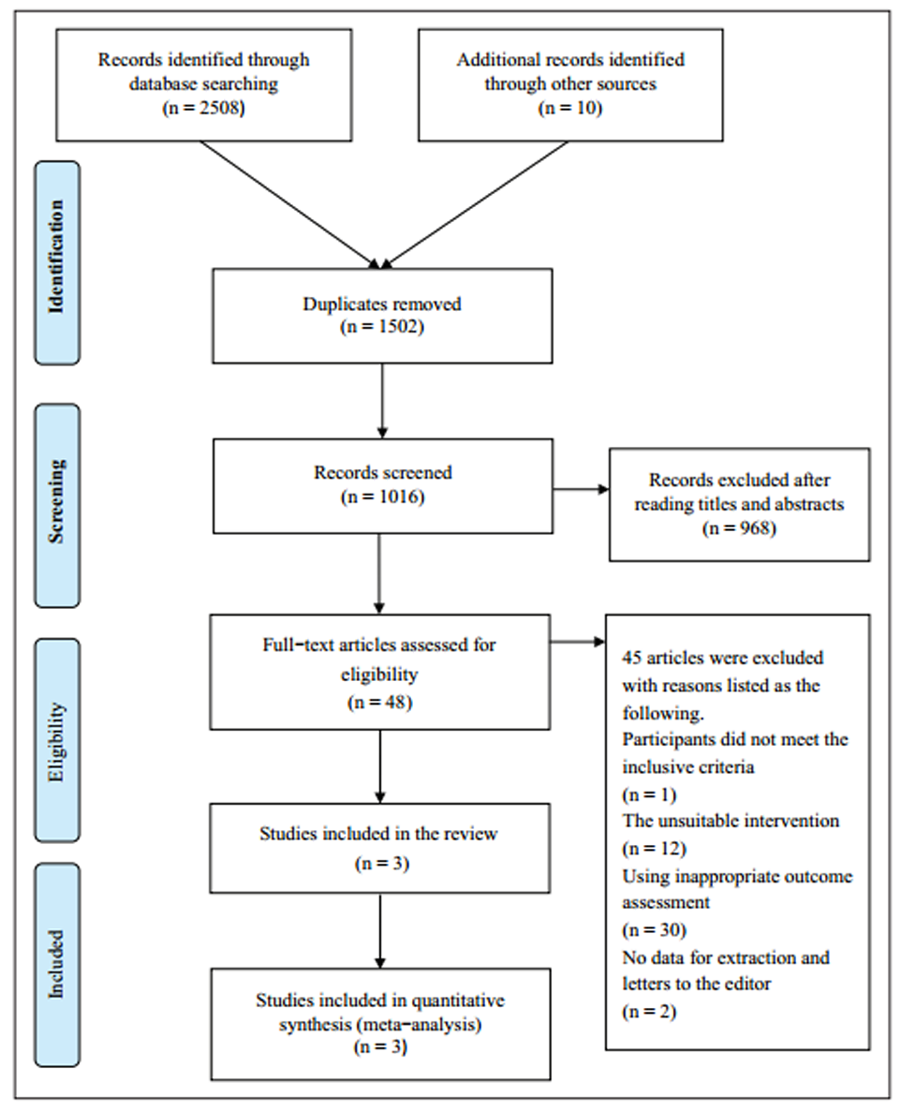

Figure 1

Table 1

Table 2

Figure 2

Table 3 A flowchart depicted the literature search process and clinical study selection (Figure 1 gives details of the included and excluded studies). A total of 2518 articles were identified by the initial search. After 1,502 duplicates were removed, 1,016 articles were screened. After reading the titles and abstracts, 968 articles of them were excluded. Full texts of 48 articles were retrieved, and finally three randomized controlled trials were included. [35–37] All the studies were published in Chinese.

The characteristics of the included trials are summarized in Table 1. The number of patients with degenerative cervical radiculopathy was 502. There was a wide variation in the average age of each group (45–53.6years). Two different diagnostic criteria of cervical radiculopathy were used in the included studies: Two trials adopted the Summary of diagnostic criteria in the second special forum of cervical spondylosis organized by the Chinese Medical Association in 1993. [35, 36, 38] Another trial reported Diagnostic and therapeutic effect criteria for diseases and syndromes in traditional Chinese medicine issued by State Administration of traditional Chinese medicine in 1994. [37, 39] Two diagnostic criteria were almost the same for the main symptoms and signs, imaging examination.

All of the trials had two arms. The interventions included three types of manipulation in the fields, and the controls only comprised cervical traction. (The different manipulative therapies are presented later in Table 3.) The treatment duration ranged from two to four weeks. Only one trial related to one month follow-up. [36] One trial described an adverse event. [37] All the visual analogue scale (VAS) scores were on neck and aim pain; the most severe pain intensity was recorded.

Methodological quality of included trials

As shown in Table 2, methodological quality scores of the included studies ranged from 5 to 6 points according to the PEDro scale. The PEDro scale predetermined score cut-off 5 was met or exceeded by all the studies included, but two in three trials just reached the limit of the cut-off score. Items 2, 4, 8, 10, 11 (random allocation, similar at baseline, less than 15% drop-out, between-group statistical comparisons, point measures and measures of variability) all counted a point on each article. However, items 5–7, 9 (subjects, therapists, assessors blinded, intention-to-treat analysis) scored a zero for all the studies. In the clinical studies of spine manipulation, blindness implementation was difficult for patients and therapists, even impossible to design. [40] As for the assessors being blinded, no details were found in all three articles. In addition, only one trial mentioned the allocation concealment. [35]

Effect of the interventions

Only one meta-analysis was conducted with a forest plot as shown in Figure 2. All the control groups of included trials used cervical computer traction. Three trials compared cervical spine manipulation alone with cervical computer traction. Of these, all trials compared cervical rotational manipulation vs. cervical computer traction (20 minutes daily), cervical rotation–traction manipulation vs. cervical computer traction (30 minutes daily), cervical fixpoint traction manipulation vs. cervical computer traction (30 minutes daily), respectively. A significant difference was found in the VAS in all three trials (Table 3). [34–36] This meta-analysis was made on the VAS-change scores.

Our research used a random effect model. The result indicated a high heterogeneity among the studies (Chi2=8.57, P=0.01, I2=77%; three trials). Meta-analysis suggested that cervical spine manipulation showed superior immediate effects compared with cervical computer traction in improving VAS for pain (n=502; MD: 1.28, 95% CI: 0.80 to 1.75; P<0.00001).

The overall level of evidence was judged to be moderate quality. The main reasons for downgrading were limitations in inconsistency of results (downgraded when there was statistical heterogeneity (I2 > 50%)). No studies were upgraded.

Only one trial reported the adverse events and none were observed in the trial with a small sample size. [36] The other two trials did not mention whether adverse events have occurred in the intervention or control group. Because of the limited number of trials (less than 10), additional analysis of sensitivity, subgroup and publication bias could not be conducted.

Discussion

Summary of the evidence

Cervical spine manipulation has played an important role in the development of traditional Chinese medicine over the last decade in China. [14] At the same time cervical manipulation has been accepted and favored by clinicians, chiropractors and physiotherapists around the world. Neck pain is the most common symptom of cervical radiculopathy, having an impact on cervical vertebra range of motion and function. In our systematic review, moderatelevel evidence from three trials suggested that cervical spine manipulation appears to be beneficial, providing immediate effect on pain relief in patients with degenerative cervical radiculopathy. Cervical computer traction is the single active control therapy in the included studies.

Comparison with the literature

So far, eight intervention systematic reviews about the non-invasive treatment for cervical radiculopathy could be retrieved in the seven electric databases. [2, 21–27] However, each systematic review included a variety of conservative intervention or complex intervention. Few studies related to the sole cervical rotational manipulation, thus making it difficult to isolate the therapeutic effect of cervical manipulation as a stand-alone intervention. Besides that, two systematic reviews were qualitative analysis and Chinese randomized controlled trials were not contained in all articles. [22–23]

Another previous systematic review by Lin et al. [41] was about Chinese manipulation on mechanic neck pain. The authors included different types of cervical spondylosis, whereas we only paid attention to cervical radiculopathy. On the other hand, in our review, outcome measurement tools had been validated and used by many other studies. But in the study by Lin et al., the outcome assessment system for cervical spondylosis radiculopathy (OASCSR) had not been peer-reviewed by experts outside China.

Strengths and limitations

Up to present, there was no systematic review of randomized controlled trials on treatment by cervical manipulation and measurement with the pain scores in the field of cervical radiculopathy. This is the first systematic review on the effectiveness and safety of cervical spine manipulation aimed at patients with cervical radiculopathy. Nonetheless, there are still some limitations in the review.

First of all, the methodological quality of primary studies played an important role in each of reviews. The PEDro scale, often used to evaluate physiotherapy evidence, was applied to assess the quality of included randomized controlled trials in this review. [42] All the trials described randomization procedures, but two out of three trials reported the specific methods including central randomization and computer software. [36–37] Only one trial has not stated the random allocation with detailed information. [35] At the same time, strict implementation of random sequence must be secured through allocation concealment. In the review, two trials failed to mention the concealed allocation in details. [35, 37] All articles clearly pointed out withdraw or drop-out, but three articles did not use intention-to-treat analysis. In these articles, the authors did not report drop-out cases in the final analysis. None of trials had a pretrial estimation of sample size. The treatment duration of included trials was short, varying from two to four weeks, and only one trial designed a one-month follow-up. [36] There was no comparison between manipulation and no treatment, placebo or other therapies (except cervical traction) in the eligible studies.

Moreover, there was lack of adverse event reports for the included studies. One out of three trials mentioned the safety of cervical manipulation and none was observed in the study. [37] In other studies, there was simply no mention of adverse events whatsoever. Owing to the limited information, we could not arrive at the conclusion on the safety of cervical spine manipulation. Therefore, the record of adverse events should be added in study design and reported according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement extension on harms reporting guidelines in the future studies of manipulative therapy. Yet despite all that, a causal relationship between treatment and the potential serious adverse event and such relation was really difficult to establish. The limited high quality research that, to our best knowledge, is available on adverse events in relation to manipulation did not suggest a causal pathway. [43–45]

Last but not the least, all of the studies screened after completing the searches were published in Chinese. Regrettably, all randomized controlled trials have not yet completed registration through there international clinical trials registry platform. There was still a risk that we missed relevant studies by not including other search terms, such as underlying pathogeneses resulting in cervical radiculopathy. Retrieval languages of literatures were restricted in English and Chinese. Some other languages published literatures could not be completely searched. Therefore, it is not clear whether potential publication bias could be eliminated fully.

Above all, cervical spine manipulation showed significant immediate effects in improving pain scores compared with cervical computer traction. Long-term effects of cervical rotational manipulation were not observed. The safety of cervical rotational manipulation for degenerative cervical radiculopathy cannot be taken as an exact conclusion. Overall, there was moderate-level evidence of cervical rotational manipulation for cervical radiculopathy. More strict clinical controlled trials are needed to generate a high level of evidence.

Clinical messages

There was evidence from three trials of moderate quality that supported

cervical spine manipulation in treating people with degenerative

cervical radiculopathy.The adverse event of cervical spine manipulation in treating degenerative

cervical radiculopathy was not clear.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the National Science and Technology Program of China [no. 2006BAI04A09 and no. 2014BAI08B06] and the Science and Technology Program of China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences [no. YS1304].

References:

Carette S and Fehlings MG.

Cervical radiculopathy.

New England J Med 2005; 353: 392–399.Thoomes EJ, Scholten-Peeters W, Koes B, et al.

The effectiveness of conservative treatment for patients with cervical radiculopathy: A systematic review.

Clin J Pain 2013; 29: 1073–1086.Shi Q.

Attentional study in cervical spondylosis [in Chinese].

Zhongguo Zhong Yi Gu Shang Ke Za Zhi 1999; 7: 1–3.Zhu LG and Yu J.

The research progress of nonoperative treatment for cervical radiculopathy [in Chinese].

Zhongguo Zhong Yi Gu Shang Ke Za Zhi 2011; 19: 66–69.Kim KT and Kim YB.

Cervical Radiculopathy due to cervical degenerative diseases: Anatomy, diagnosis and treatment.

J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2010; 48: 473–479.Costello M.

Treatment of a patient with cervical radiculopathy using thoracic spine thrust manipulation, soft tissue mobilization, and exercise.

J Manip Physiolog Therapeut 2008; 16: 129–135.Hurwitz, EL, Carragee, EJ, van der Velde, G et al.

Treatment of Neck Pain: Noninvasive Interventions: Results of the Bone and Joint Decade

2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008 (Feb 15); 33 (4 Suppl): S123–152Vonkemon HE and Van de Laar MA.

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: Adverse effects and their prevention.

Seminars Arth Rheumat 2010; 39: 294–312.Eubanks JD.

Cervical radiculopathy: Nonoperative management of neck pain and radicular symptoms.

Am Fam Physician 2010; 81: 33–40.Forbush SW, Cox T and Wilson E.

Treatment of patients with degenerative cervical radiculopathy using a multimodal conservative approach in a geriatric population: A case series.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2011; 41: 723–733.Peterson CK, Schmid C, Leemann S, Anklin B, Humphreys BK.

Outcomes From Magnetic Resonance Imaging–Confirmed Symptomatic Cervical Disk

Herniation Patients Treated With High-Velocity, Low-Amplitude Spinal Manipulative

Therapy: A Prospective Cohort Study With 3-Month Follow-Up

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2013 (Oct); 36 (8): 461–467Maigne JY and Vautravers P.

Mechanism of action of spinal manipulative therapy.

Joint Bone Spine 2003; 70: 336–341.Song YT.

Traditional Chinese manipulation [in Chinese].

Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 1995; S2: 62–67.Wang HM.

Origin and development of spinal rotation massage [in Chinese].

Fujian Zhong Yi Xue Yuan Xue Bao 2007; 17: 37–39.Leaver AM, Maher CG, Herbert RD, et al.

A randomized controlled trial compared manipulation with mobilization for reset onset neck pain.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010; 91: 1313–1318.Millan M, Leboeuf-Yde C, Budgell B, et al.

The effect of spinal manipulative therapy on spinal range of motion: A systematic literature review.

Chiropractic Manual Therapies 2012; 20: 23.Gert Bronfort DC, PhD; Roni Evans DC; Brian Nelson MD; Peter D. Aker DC, MSc; et al.

A Randomized Clinical Trial of Exercise and Spinal Manipulation

for Patients with Chronic Neck Pain

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001 (Apr 1); 26 (7): 788–797Li YK, Zhao WD and Zhong SZ.

A comparative study on the crackings during two rotatory manipulations of the neck [in Chinese].

Zhong Yi Zheng Gu 1998; 10: 9–10.Evans DW.

Mechanisms and Effects of Spinal High-velocity, Low-amplitude Thrust Manipulation:

Previous Theories

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2002 (May); 25 (4): 251–262R. Bryans, P. Decina, M. Descarreaux, et al.,

Evidence-Based Guidelines for the Chiropractic Treatment of Adults With Neck Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2014 (Jan); 37 (1): 42–63Salt E, Wright C, Kelly S, et al.

A systematic literature review on the effectiveness of non-invasive therapy for cervicobrachial pain.

Manual Therapy 2011; 16: 53–56.Boyles R, Toy P, Jr JM, et al.

Effectiveness of manual physical therapy in the treatment of cervical radiculopathy: A systematic review.

J Manual Manipulative Therapy 2011; 19: 135–142.Rodine RJ and Vernon H.

Cervical radiculopathy: a systematic review on treatment by spinal manipulation and measurement with the Neck Disability Index.

J Can Chiropractic Assoc 2012; 56: 18–28.Leininger B, Bronfort G, Evans R, et al.

Spinal manipulation or mobilization for radiculopathy: A systematic review.

Phys Med Rehabil Clinics N Am 2011; 22: 105–125.Guo K, Li L, Zhan HS, et al.

Manipulation or massage on nerve-root-type cervical spondylosis systematic review of clinical randomized controlled trials [in Chinese].

Huan Qiu Zhong Yi Yao 2012; 5: 3–7.Wang YG, Guo XQ, Zhang Q, et al.

Systematic review on manipulative or massage therapy in the treatment of cervical spondylotic radiculopathy [in Chinese].

Zhonghua Zhong Yi Yao Za Zhi 2013; 28: 499–503.Yang J, Zhang RC and Wang XJ.

Meta-analysis on nerveroot-type cervical spondylosis treatment by manipulation or massage and cervical traction [in Chinese].

Huan Qiu Zhong Yi Yao 2013; 6: 641–648.Bono CM, Ghiselli G, Gilbert TJ, et al.

An evidence-based clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of cervical radiculopathy from degenerative disorders.

Spine J 2011; 11: 64–72.American Physical Therapy Association.

Guide to physical therapist practice (Second Edition).

Physical Therapy 2001; 81: 9–746. Avialable at:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11175682Physiotherapy evidence database.

PEDro scale, http://www.pedro.org.au/english/downloads/pedro-scale/

(1999, accessed 28 December 2014).Maher CG.

A systematic review of workplace interventions to prevent low back pain.

The Australian J Physiother 2000; 46: 259–269.Higgins JPT and Green S.

Cochrane Reviewers’ Handbook 5.1.0, Review Manager (RevMan), Version 5.2.0,

http://handbook.cochrane.org/

(2011, accessed 25 December 2014).Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al.

GRADE: An Emerging Consensus on Rating Quality of Evidence

and Strength of Recommendations

British Medical Journal 2008 (Apr 26); 336 (7650): 924–926Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al.

GRADE: What is “Quality of Evidence” and why is it important to clinicians?

BMJ 2008, 336: 995–998.Zhu LG, Yu J and Gao JH.

Clinical study of effect of rotational manipulation in treating cervical spondylotic radiculopathy using visual analog scales [in Chinese].

Beijing Zhong Yi Yao 2005; 24: 297–298.Zhu LG, Yu J and Gao JH.

The measurement of pain and numbness in patients with cervical spondylotic radiculopathy [in Chinese].

Zhongguo Zhong Yi Gu Shang Ke Za Zhi 2009; 17: 1–3.Jiang CB, Wang J, Zheng ZX, et al.

Efficacy of cervical fixed-point traction manipulation for cervical spondylotic radiculopathy: A randomized controlled trial [in Chinese].

Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao 2012; 10: 54–58.Sun Y and Chen QF.

Summary in the second special forum of cervical spondylosis [in Chinese].

Zhonghua Wai ke Za Zhi 1993; 31: 472–476.State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Diagnostic and therapeutic effect criteria for diseases and syndromes in traditional Chinese medicine [in Chinese].

Nanjing: Nanjing University Press, 1994, 186.Kong LJ, Zhan HS, Chen YW, et al.

Massage therapy for neck and shoulder pain: A systematic review and metaanalysis.

Evidence-Based Complementary Altern Med 2013; 83: 713–721.Lin JH, Chiu TTW and Hu J.

Chinese manipulation for mechanical neck pain: A systematic review.

Clin Rehabil 2012; 26: 963–973.Elkins MR, Moseley AM, Sherrington C, et al.

Growth in the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) and use of the PEDro scale.

Brit J Sports Med 2013; 47: 188–189.Rubinstein SM, Leboeuf-Yde C, Knol DL, de Koekkoek TE,

Pfeifle CE, van Tulder MW.

The Benefits Outweigh the Risks for Patients Undergoing Chiropractic

Care for Neck Pain A Prospective, Multicenter, Cohort Study

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2007 (Jul); 30 (6): 408–418Cassidy JD, Boyle E, Cote P, et al.

Risk of Vertebrobasilar Stroke and Chiropractic Care: Results of a

Population-based Case-control and Case-crossover Study

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008 (Feb 15); 33 (4 Suppl): S176–183Maiers et al., 2015

M. Maiers, R. Evans, J. Hartvigsen, C. Schulz, G. Bronfort

Adverse Events Among Seniors Receiving Spinal Manipulation and Exercise

in a Randomized Clinical Trial

Manual Therapy 2015 (Apr); 20 (2): 335–341

Return to RADICULOPATHY

Return to DISC HERNIATION

Return to CHRONIC NECK PAIN

Return to SPINAL PAIN MANAGEMENT

Since 6-04-2016

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |