Observational Study of the Safety of Chiropractic

vs Medical Care Among Older Adults With Neck PainThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2025 (Sep 9): S0161-4754(25)00002-8 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS ACC RAC Award Winning Paper

James M. Whedon, DC, MS • Brian Anderson, DC, PhD • Todd A. Mackenzie, PhD • Leah Grout, PhD • Steffany Moonaz, PhD • Jon D. Lurie, MD, MS • Scott Haldeman, DC, MD, PhD

Clinical & Health Services Research,

Southern California University of Health Sciences,

Whittier, California.

Objective: The purpose of this study was to evaluate the risk of selected adverse outcomes for older adults with a new episode of Neck Pain (NP) receiving chiropractic care compared to those receiving Primary Medical Care with Prescription Drug Therapy (PDT) or Primary Medical Care without Prescription Drug Therapy (PCO = Primary Care Only).

Methods: Through analysis of Medicare claims data, we designed a retrospective cohort study including 291,604 patients with a new office visit for NP in 2019. We developed 3 mutually exclusive exposure groups:the Chiropractic Manipulative Therapy (CMT) group received spinal manipulative therapy from a chiropractor with no primary care visits;

the Primary Medical Care with Prescription Drug Therapy (PDT) group visited primary care and filled an analgesic prescription within 7 days without chiropractic care, and

the Primary Care Only (PCO) group visited primary care without chiropractic care or analgesic prescriptions.We analyzed possible complications, including adverse drug events, vertebrobasilar insufficiency, and other selected adverse outcomes, calculating incidence rate ratios over 24 months using Poisson regression with robust standard errors and inverse propensity weighing to balance the exposure groups regarding patient characteristics.

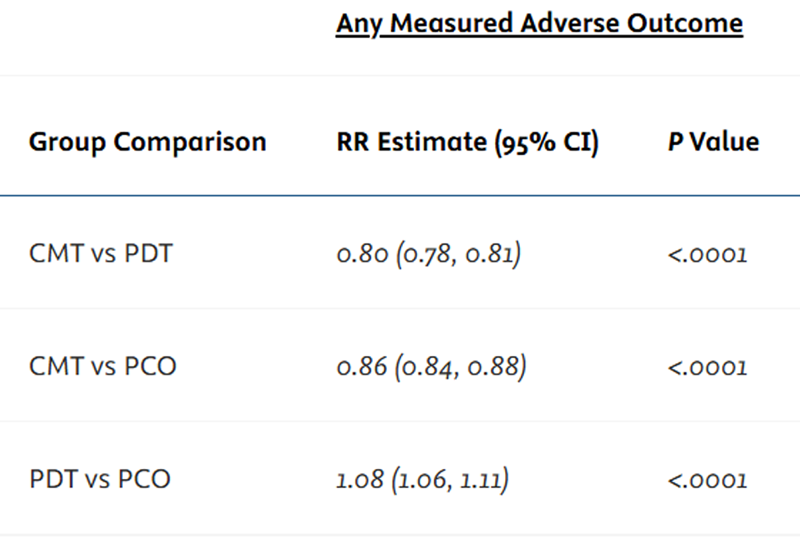

Results: Among 291,604 patients, 182,596 (63%) received chiropractic care. For CMT vs PDT, the rate for any measured adverse outcome was 20% lower; for CMT vs PCO, the rate was 14% lower, and for PDT vs PCO, the rate was 6% higher. PDT had the highest risk of any measured adverse outcome.

Conclusion: For Medicare Part B beneficiaries with new onset NP, management with chiropractic care was associated with lower rates of adverse events than primary medical care. The PDT group had the highest risk of any measured adverse outcome.

Keywords: Chiropractic; Manipulation, Spinal; Medicare; Neck Pain; Safety.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Neck pain (NP) is one of the most common musculoskeletal disorders in the United States (US), with an age standardized point prevalence of approximately 16%. [1] The prevalence of NP increases with age, peaking at age 65 to 69, [2] but the management of NP is prone to the utilization of interventions that may be harmful, particularly for the aged. [3] Older adults receive more opioid analgesics than people in other age groups, [4] and the elderly are at high risk of opioid-related adverse events. [5]

Analgesics are among the drug types most often associated with an adverse drug event (ADE), [6] and clinicians are cautioned against long-term use of both NSAIDS and opioids in older patients with chronic pain due to safety concerns. [7] Long-term use of NSAIDs is associated with gastrointestinal, renal, cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and neurological adverse effects. [8, 9] The safety of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain is of particular concern due to multiple adverse effects, including opioid use disorder, overdose, and death. [10] Nevertheless, opioid prescribing is often prolonged, particularly in certain vulnerable populations, including the elderly. [11]

Clinical practice guidelines for management of NP discourage the use of Prescription Drug Therapy (PDT) and emphasize the use of conservative nonpharmacological therapies such as spinal manipulative therapy, which is most commonly performed by chiropractors. [12] A recent review identified clinical practice guidelines on chiropractic and spinal manipulation for NP [13], all of which favored nonpharmacological and multimodal care including spinal manipulation. [14] However, the authors noted that gaps in evidence remain regarding the long-term safety of spinal manipulation.

Although there is no conclusive evidence indicating that long-term spinal manipulation is harmful, it has been hypothesized that cervical spine manipulation may contribute to vertebral artery dissection (VAD), a known risk factor for vertebrobasilar stroke. [15, 16] A temporal association between spinal manipulation and VAD has been reported, although VAD occurs more frequently in middle-aged individuals than in older adults. [15] Subsequent research suggests that this association is unlikely to be causal and is more plausibly explained by care-seeking behavior rather than by spinal manipulation itself. [17] Nevertheless, the potential risk of VAD continues to be a topic of concern. [18]

Adverse outcomes of manipulation of the cervical spine are uncommon; when they do occur, they are generally mild and transient. [19] A recent systematic review found that risk of adverse outcomes may be lower for patients that received manual therapy as compared to those treated with analgesics. [20]

The comparative safety of chiropractic vs primary medical care for treatment of NP has not been rigorously evaluated. In this study, we analyzed Medicare Part B claims data for adults aged 65 to 99 with newly diagnosed NP to compare management strategies involving Chiropractic Manipulative Therapy (CMT) vs primary care — both with and without initial PDT — with respect to the risk of serious adverse outcomes. These outcomes included spinal injury, VAD, stroke, and complications potentially associated with the use of analgesic medications.

Methods

Design and Data Sources

We hypothesized that among aged Medicare beneficiaries with NP, as compared with recipients of primary care, recipients of chiropractic care would have a lower risk of serious adverse outcomes. To test this hypothesis, we employed a retrospective cohort design using paid Medicare claims and administrative data for the years 2018 to 2021, accessed under a data use agreement from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. General methods for similar research using Medicare administrative data to evaluate the risk of serious adverse events have been described previously.21

Population

The study population included noninstitutionalized Medicare Part B beneficiaries aged 65 to 99 years, residing in a US state or the District of Columbia, and continuously enrolled under Medicare Parts A, B, and D for the 48-month period from 2018 through 2021. We restricted the included beneficiaries to those with an office visit in 2019 for a new episode of NP as identified by primary ICD-10 diagnosis code (see Supplementary File for Appendix). We defined a new episode of NP as beginning with the recording of at least 1 paid claim with a primary diagnosis of NP, preceded by a 90-day washout period with no paid claims for NP. For beneficiaries with more than 1 episode of NP, only the first episode was counted. We excluded beneficiaries with a diagnosis of cancer or use of hospice care or a skilled nursing facility to avoid confounding of the indication for prescribing opioids.

Exposure Groups

Three mutually exclusive exposure groups were identified based on the approach to clinical management for a new episode of NP in 2019. The CMT group received spinal manipulation from a Doctor of Chiropractic (procedure code 98940, 98941, or 98942; provider specialty code 35) and no primary medical care for a primary diagnosis of NP during the episode.

Patients in the PDT group visited a primary care physician (provider specialty code 01, 08, or 11), filled a prescription for an analgesic within 7 days of the initial visit, and received no spinal manipulative therapy for primary diagnosis of NP during the episode.

The Primary Care Only (PCO) group was defined in the same way as the PDT group, except that the patients did not fill a prescription for an analgesic within 7 days of initial visit. Analgesic medications were identified by 10-digit National Drug Codes present in Medicare Part D encounter data and were selected based on treatment guidelines22 and expert opinion (coauthor JDL).

Independent Variables

Demographic characteristics, comorbid conditions, and Charlson Comorbidity Index scores were identified utilizing Medicare Parts A and B data from the 12-month period preceding the date of the initial office visit (index date). The Research Triangle Institute race codes [23] were collapsed from 7 categories into 4 due to small frequencies. Two markers of low-income (dual enrollment in Medicare/Medicaid and Part D subsidy) were collapsed into 1 indicator of low-income, as the correlation among these variables was near 100%. Beneficiaries with either marker were classified as low-income. Comorbid chronic conditions were selected based on a study of patients with pain disorders seeking primary care in the US. [24]

Outcome Measurement

We measured counts of serious adverse outcomes as recorded by diagnosis code for outpatient encounters among the 3 exposure groups at 24 months following the date of initial visit for NP. We analyzed complications of PDT, including ADEs such as overdoses, opioid addiction or abuse, and other substance use disorders. Diagnosis codes for ADEs specify the drug involved, facilitating higher accuracy in identifying these events. In addition to searching for explicit documentation of ADE, we searched claims for other serious adverse outcomes that are associated with analgesic use (gastrointestinal bleeding, renal failure, stroke, and myocardial infarction) but also occur without exposure to analgesics. We also evaluated the likelihood of serious injuries and complications that may be associated with spinal manipulative therapy of the cervical spine, including soft tissue injury, cervical spine dislocation, cervical spine fracture, VAD, vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI), and vertebrobasilar stroke.

Statistical Analysis

To account for variability in episode duration among beneficiaries, we calculated time-standardized incidence rates for selected adverse outcomes across exposure groups. This involved aggregating data on adverse outcomes as well as person-years for each group.

The incidence rates per 1000 person-years were determined using the formula:

× (1000).

We then estimated differences in rate by group. Similarly, we calculated incidence rates for “Any Selected Adverse Outcome” by aggregating all adverse outcomes by group over the 2-year follow-up period. We estimated incidence rate ratios (RR) comparing CMT and PDT groups to the PCO group (reference group) using Poisson regression with robust standard errors. [25]

Our models were adjusted for a comprehensive set of individual characteristics and health status indicators, including: age at the start of 2019, age category, sex, Research Triangle Institute race code, low-income marker, and a range of chronic conditions (hip or knee osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, opioid use disorder, depression, and low back pain). The Charlson Comorbidity Index score, categorized into 5 groups, was integrated as a measure of baseline health status. In addition, we incorporated balancing between the CMT, PDT, and PCO groups using inverse propensity weighting.

We employed multinomial logistic regression to compute propensities for each of the therapies based on the covariates listed above. We included all covariates in the multivariable Poisson regression with robust standard errors (doubly-robust estimation) to overcome any limitations in the ability of the propensity weights to optimally balance the exposure groups. [25, 26] This process was performed individually for each type of adverse outcome, as well as for aggregated adverse outcomes (total adverse outcomes). Least squares means (LSMEANS) were calculated using the GENMOD procedure in SAS. [27] LSMEANS provide adjusted means for each level of a variable, considering the influence of model covariates. These adjusted means are interpretable as risk ratios. We followed Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) rules for data suppression to protect patient confidentiality. All analyses were conducted in SAS (SAS version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc.). [28]

Results

Table 1 Application of all inclusion and exclusion criteria to the study sample resulted in 291,604 patients with an office visit for NP, of whom 182,596 (63%) saw a chiropractor and received spinal manipulative therapy. Claims with specialty code 35 were 100% congruent with at least 1 of the 3 procedure codes for spinal manipulative therapy; thus, spinal manipulative therapy and chiropractic care were essentially synonymous under Medicare during the study period. 109,008 patients (37%) visited a primary care physician for NP (Table 1). Among those with a primary care visit, 85,765 patients (29% of total) did not fill a prescription for an analgesic within 7 days of their initial visit, while 23,243 patients (8% of total) did fill an analgesic prescription within 7 days. Thus, there were 182,596 patients in the CMT group, 23,243 in the PDT group, and 85,765 in the PCO group.

In comparison with the PCO and PDT groups, the CMT group was younger, had higher income, and was less racially and ethnically diverse, with Whites comprising 92% of the group, as compared to 81% for PCO and 82% for PDT. Comorbid low back pain was much more prevalent in the CMT group, while osteoarthritis of the hip or knee and opioid use disorder were less prevalent in the CMT group.

The classes of medications prescribed for the PDT group consisted ofcorticosteroids (35%),

muscle relaxants (27%),

opioids (16%),

NSAIDS (12%),

gabapentenoids (6%), and

antidepressants (4%).We detected a total of 14,285 outpatient encounters for adverse drug event (ADE), with sufficient statistical power to reveal significant differences in risk by group.

Table 2 shows rates of adverse outcomes by exposure group. The most common adverse outcomes were stroke, renal failure, and gastrointestinal bleeding. The CMT group experienced lower rates of any measured adverse outcome as compared to recipients of primary care, with or without PDT. For recipients of primary care with or without PDT, crude differences in rates of any selected adverse outcome were more than 7 events per thousand person-years higher than in the CMT group. In all specific outcome categories, crude rates for adverse outcomes were higher for PCO and PDT as compared to CMT. Rates of potential adverse outcomes of spinal manipulative therapy (soft tissue injury, cervical spine dislocation or fracture, VAD, and vertebrobasilar stroke) were all too low to report for all groups according to CMS rules for data suppression.

Table 3 displays the comparative risk of adverse outcomes for the CMT and PDT groups with reference to the PCO group, with results for both unweighted and propensity-weighted regression models. Weighting caused relatively small changes in risk ratios and in the width of confidence intervals, but no changes in statistical significance.

Adverse Outcomes In the weighted model, as compared to PCO, the comparative risk of any measured adverse outcome was 14% lower for CMT and 8% higher for PDT. Analysis for specific adverse outcomes revealed that the risk in the CMT group was 59% lower for ADE, 22% lower for renal failure, and 9% lower for gastrointestinal bleeding. As compared to the PCO group, the rate of gastrointestinal bleeding was 9% lower for CMT and 14% higher for PDT. We found no significant differences in risk for myocardial infection, stroke, or VBI. Regarding patient characteristics, the weighted model shows that low-income is associated with increased risk for any measured adverse outcome, ADEs, and VBI.

Female sex is associated with lower risk than males for all outcomes except ADEs. RR estimates generally increase with Charlson Comorbidity Index score, except in the 4+ category; the same correlation is also seen for age category. Whites generally have the highest rates of adverse outcomes, except for ADEs. Chronic conditions, except osteoarthritis of the hip, are highly associated with any measured adverse outcome. Table 4 compares RR for any measured adverse outcome, estimated via LSMEANS and weighted and adjusted as in the full regression model. For CMT vs PDT, the RR was 20% lower, for CMT vs PCO, the RR was 14% lower, and for PDT vs PCO, the RR was 6% higher. The RR estimate of 1.06 for the PDT group indicates that among the 3 groups, PDT had the highest risk of any measured adverse outcome.

Discussion

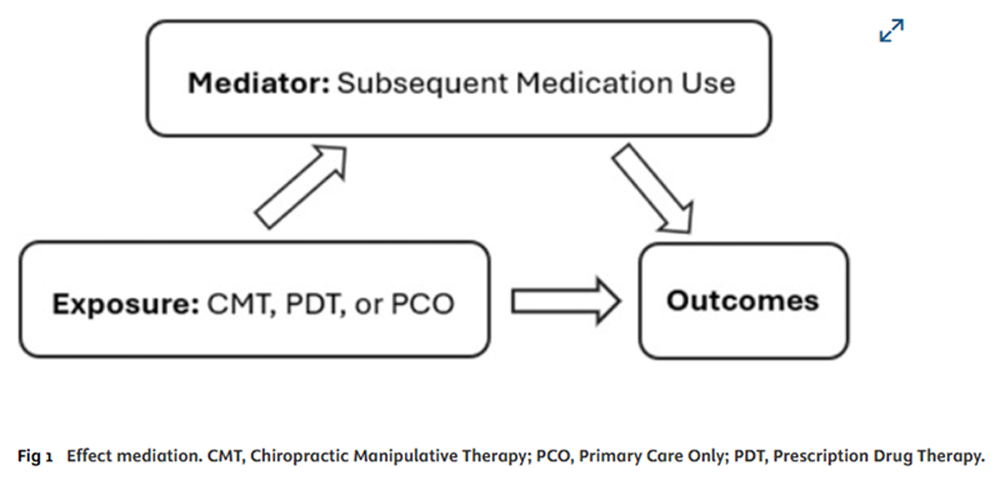

Figure 1 Among Medicare Part B beneficiaries with newly diagnosed NP, management with chiropractic care was associated with lower rates of adverse outcomes compared to primary care. These differences are likely mediated by variations in medication use following the initial treatment (Figure 1).

Patient characteristics, as summarized by exposure group in Table 1 are generally consistent with reports on Medicare beneficiaries with low back pain. However, unlike studies of low back pain, a substantial proportion of participants in our investigation opted for chiropractic care (CMT) over primary care as the treatment modality for NP, a finding which aligns with previous studies of patients with NP.

Fenton et al [29] reported that 45% of patients presenting with a new episode of NP saw a chiropractor first, in contrast to 33% who initiated care with a primary care physician. Similarly, Whedon et al [30] found that, among Medicare beneficiaries with NP, 65% of individuals initially sought chiropractic care, whereas 45% consulted a primary care physician.

Finally, a recent scoping review of 33 studies evaluating chronic pain management strategies among Medicare beneficiaries found that spinal manipulation was the most common noninvasive, nonpharmacological option chosen. [31] In the current study the higher proportion of patients in the CMT group may also be attributed in part to the fact that we restricted the analysis to 4 clinical specialties (chiropractic and 3 primary specialties: family medicine, internal medicine, and general practice).

Of all included patients, only 8% received prescription pharmacotherapy initially. Because most cases of NP can be successfully managed with conservative nonpharmacological care, [12] the fact that only 8% of patients received prescription pharmacotherapy initially suggests that the management of NP may have been congruent with clinical practice guidelines, which emphasize conservative nonpharmacological care. For older Medicare Part B beneficiaries with new onset NP, we found that the cumulative risk at 24 months of any selected adverse outcome was significantly lower in the CMT group, as compared to those who received primary medical care.

This result is consistent with a study that found lower rates of ADE for initial management with chiropractic care compared to primary care among Medicare patients with low back pain, [32] and congruent with reports that — among Medicare patients with NP management with chiropractic care is associated with less escalation of care and lower costs as compared to primary care. [33, 34] In the following sections we discuss the results on comparative risk for each category of adverse outcome.

Adverse Drug Events

Each of the drug classes that were prescribed for the PDT group are commonly prescribed for spinal pain, and all have been associated with risk of ADE. [22] Budnitz et al [35] reported that analgesics (including opioids, NSAIDs and muscle relaxants) were the most commonly implicated class of medication in encounters for ADE (13.9% of visits, although drug use was therapeutic in only 1/3 of cases). The lower risk of ADE in the CMT group was expected because medication prescribing privileges fall outside the scope of practice of most chiropractors.

Populations that may be at greater risk of ADE include older adults, individuals with low socioeconomic status, and racial/ethnic minorities. [36] As noted in the results, in comparison with the PCO and PDT groups, the CMT group was younger, had higher income, and was less diverse with Whites comprising 92% of the group; these characteristics were accounted for in our analysis through regression modelling and propensity weighting.

Many ADEs can be prevented through strategies that target prescribing practices. [3, 37] Adoption of conservative prescribing practices is critically important for older adults, many of whom are at increased risk for ADE, due to drug metabolism changes, frailty, multimorbidity, geriatric syndromes, cognitive and sensory impairment, and polypharmacy. [38] A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that interventions intended to reduce ADEs in older adults have a significant and substantial effect. [39] However, none of the included interventions focused on the use of chiropractic care as an alternative to medication. Future interventional research should evaluate the effect of offering nonpharmacological therapy to patients with pain disorders as an intervention to continue to reduce the incidence of ADE.

Gastrointestinal Bleeding and Renal Failure

The higher rates of gastrointestinal bleeding and renal failure for the PDT group were expected because analgesic medication is well established as a cause of gastrointestinal bleeding and renal disease [8]; there is no evidence to suggest a relationship between chiropractic care and development of these conditions.

VAD and Stroke

For both VAD and vertebrobasilar stroke — the type of stroke that can be precipitated by VAD — the incidence was too low to report under Medicare data suppression policies, which restrict disclosure of event counts between 1 and 10. The annual incidence rate of VAD has been reported to be 0.97 per 100,000 population [40] The results of previous studies in the Medicare Part B population are consistent with our findings. The incidence of vertebrobasilar stroke was also too small to report in a study of over 1.1 million older Medicare beneficiaries with an office visit to either a chiropractor or primary care physician for NP. [41] A subsequent study of older Medicare beneficiaries with NP found no greater risk of VAD for recipients of chiropractic care than for controls. [42]

Vertebrobasilar Insufficiency

Although VBI is considered a chronic condition, it can also occur secondary to VAD, which may be spontaneous or trauma-induced. VAD has been temporally associated with cervical spine manipulation. However, in our analysis, we found no significant differences in the risk of VBI across exposure groups.

Risk of Other Adverse Outcomes That Have Been Attributed to CMT

Whedon et al [43] reported that among older Medicare beneficiaries with an office visit for a neuromusculoskeletal problem, the risk of injury to the head, neck, or trunk within 7 days was 76% lower among patients with a chiropractic office visit than among those who saw a primary care physician. The very low risk of cervical spine injury associated with chiropractic care that is suggested by the results of the current study, appear to be consistent with this earlier report.

Implications for Health Policy

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services impose stringent limitations on the reimbursement of chiropractic services; although in most states chiropractors are licensed to provide a broad scope of services, spinal manipulation is the only procedure that is paid by Medicare. [44]

The findings of this study indicate that policy revisions may be necessary, given that spinal manipulation has demonstrated effectiveness for treatment of NP, [45] and is associated with fewer adverse outcomes as compared to primary medical care.

In a reanalysis of Medicare’s demonstration of expanded coverage for chiropractic, Weeks et al [46] recommended expansion of chiropractic coverage to include evaluation and management services. The Chiropractic Medicare Coverage Modernization Act of 2025 proposes to expand Medicare coverage of chiropractic services to include all services provided by chiropractors. [47] (After approval by the Senate, that Act was signed into law by the President.)

Limitations

This study did not evaluate clinical outcomes other than adverse outcomes. The research was limited by noninclusion of Medicare Advantage plans, which now cover more than 50% of the Medicare population. Pharmacy claims data do not include diagnosis, so it is not possible to determine whether a drug was prescribed specifically for NP. However, the prescription fill was linked to the physician who diagnosed the patient. The use of nonprescription medications was not evaluated and cannot be ruled out, particularly for NSAIDS, which are widely available without prescription, and opioids, which can be obtained illicitly in different forms, including fentanyl.

The requirement of 4 years of continuous Medicare enrollment as an eligibility criterion may have introduced survivorship bias, potentially underestimating the risk of serious adverse events within the study population.

The high prevalence of comorbid LBP in the CMT group suggests the possibility of unmeasured differences between groups, and the temporal association between treatment and outcomes weakens with time.

We employed rigorous methods to minimize the risk of selection bias arising from differences in health status between exposure groups or a potential predisposition among patients in the CMT group to avoid prescription drug use, which could indicate that the groups are drawn from different populations. However, despite these measures, we were unable to account for all confounding variables, such as confounding by indication for use of analgesics.

The observational nature of our study inherently limits causal inference, and we could not explicitly assess changes in underlying health status. Additionally, while propensity scoring is a valuable tool for creating comparable groups, its effectiveness depends on the relevance and comprehensiveness of the included independent variables.

Conclusion

Among Medicare beneficiaries with newly diagnosed Neck Pain (NP),

treatment with Chiropractic Manipulative Therapy (CMT) was associated with a

20% lower rate of any measured adverse outcomes compared to

Primary Medical Care with Prescription Drug Therapy (PDT), and a14% lower rate of any measured adverse outcomes compared to

Primary Medical Care without Prescription Drug Therapy (PCO = primary care only).In contrast, the Primary Medical Care with Prescription Drug Therapy (PDT) group demonstrated a

6% higher rate of adverse outcomes relative to Primary Medical Care without Prescription Drug Therapy (PCO = primary care only).

Overall, initial management with Primary Medical Care with Prescription Drug Therapy (PDT)

was associated with the highest risk of adverse outcomes among the 3 treatment groups.

Supplementary Material

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

This research was supported by a grant from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Award Number: 2R15AT010035-02. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

Contributorship Information

Concept development (provided idea for the research): J.M.W.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): J.M.W., B.A., T.A.M., L.G., J.D.L., S.H.

Supervision (oversight, organization, and implementation): J.M.W., T.A.M., S.M.

Data collection/processing (experiments, organization, or reporting data): J.M.W., B.A.

Analysis/interpretation (analysis, evaluation, presentation of results):

J.M.W., B.A., T.A.M., L.G., S.M., J.D.L., S.H.

Literature search (performed the literature search): J.M.W.

Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): J.M.W., B.A., T.A.M.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content): J.M.W., T.A.M., L.G., S.M., J.D.L., S.H.

References:

Kazeminasab, S. Nejadghaderi, S. Amiri, P.

Neck Pain: Global Epidemiology, Trends and Risk Factors

BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2022 (Jan 3); 23 (1): 26Safiri, S. Kolahi, A. Hoy, D.

Global, Regional, and National Burden of Neck Pain in the General Population,

1990-2017: Systematic Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017

British Medical Journal 2020 (Mar 26); 368: m791Fu, J.L. Perloff, MD.

Pharmacotherapy for spine-related pain in older adults

Drugs Aging. 2022; 39:523-550Krebs, E. Paudel, M. Taylor, B.

Association of opioids with falls, fractures, and physical performance

among older men with persistent musculoskeletal pain

J Gen Internal Med. 2016; 31:463-469Solomon, D. Rassen, J. Glynn, R.

The comparative safety of opioids for nonmalignant pain in older adults

Arch Intern Med. 2010; 170:1979-1986Sakuma, M. Kanemoto, Y. Furuse, A.

Frequency and severity of adverse drug events by

medication classes: the JADE study

J Patient Saf. 2020; 16:30-35Makris, U. Abrams, R. Gurland, B.

Management of persistent pain in the older patient: a clinical review

JAMA. 2014; 312:825-836Davis, A. Robson, J.

The dangers of NSAIDs: look both ways

Br J Gen Pract. 2016; 66:172-173Marcum, Z. Hanlon, J.

Recognizing the risks of chronic nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory drug use in older adults

Ann Longterm Care. 2010; 18:24-27Chou, R. Turner, J. Devine, E.

The Effectiveness and Risks of Long-Term

Opioid Treatment of Chronic Pain

Evidence Report/Technology Assessment Number 218

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (September 2014)Tong, S. Hochheimer, C. Brooks, E.

Chronic opioid prescribing in primary care: factors and perspectives

Ann Fam Med. 2019; 17:200-206Parikh, P. Santaguida, P. Macdermid, J.

Comparison of CPG’s for the diagnosis, prognosis and management

of non-specific neck pain: a systematic review

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019; 20:81Assendelft, W. Bouter, L. Knipschild, P.

Complications of spinal manipulation: a comprehensive review of the literature

J Fam Pract. 1996; 42:475-480Trager, R.J. Bejarano, G. Perfecto, R.T.

Chiropractic and Spinal Manipulation: A Review of Research

Trends, Evidence Gaps, and Guideline Recommendations

J Clin Med 2024 (Sep 24); 13 (19): 5668Cassidy, J. Boyle, E. Cote, P.

Risk of Vertebrobasilar Stroke and Chiropractic Care:

Results of a Population-based Case-control

and Case-crossover Study

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008 (Feb 15); 33 (4 Suppl): S176–183Engelter, S. Grond-Ginsbach, C. Metso, T.

Cervical artery dissection:

trauma and other potential mechanical trigger events

Neurology. 2013; 80:1950-1957Whedon, J. Petersen, C. Li, Z.

Association Between Cervical Artery Dissection

and Spinal Manipulative Therapy -

A Medicare Claims Analysis

BMC Geriatrics 2022 (Nov 29); 22 (1): 917Pankrath, N. Nilsson, S. Ballenberger, N.

Adverse events after cervical spinal manipulation – a systematic

review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials

Pain Physician. 2024; 27:185-201Carlesso, L. Gross, A. Santaguida, P.

Adverse events associated with the use of cervical manipulation and

mobilization for the treatment of neck pain in adults:

a systematic review

Man Ther. 2010; 15:434-444Makin, J. Watson, L. Pouliopoulou, D.V.

Effectiveness and safety of manual therapy when compared with oral

pain medications in patients with neck pain:

a systematic review and meta-analysis

BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2024; 16:86Makin, J. Watson, L. Pouliopoulou, D.V.

Effectiveness and safety of manual therapy when compared with oral

pain medications in patients with neck pain:

a systematic review and meta-analysis

BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2024; 16:86Fu, J. Perloff, M.

Pharmacotherapy for spine-related pain in older adults

Drugs Aging. 2022; 39:523-550 Epub 2022 Jun 27Jarrín, O. Nyandege, A. Grafova, I.

Validity of race and ethnicity codes in Medicare administrative data

compared with gold-standard self-reported race collected

during routine home health care visits

Med Care. 2020; 58:e1-e8Stokes, A. Lundberg, D. Sheridan, B.

Association of obesity with prescription opioids for painful

conditions in patients seeking primary care in the US

JAMA Netw Open. 2020; 3, e202012Zou, G.

A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective

studies with binary data

Am J Epidemiol. 2004; 159:702-706Funk, M. Westreich, D. Wiesen, C.

Doubly robust estimation of causal effects

Am J Epidemiol. 2011; 173:761-767SAS/STAT® 14.1

User’s Guide: The GENMOD Procedure

SAS Institute Inc., 2015

https://support.sas.com/documentation/onlinedoc/stat/141/genmod.pdfLittell, R. Milliken, G. Stroup, W.

SAS® for Mixed Models

SAS Institute Inc., 2006Fenton, J. Fang, S. Ray, M.

Longitudinal Care Patterns and Utilization Among Patients

with New-Onset Neck Pain by Initial Provider Specialty

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2023 (Oct 15); 48 (20): 1409–1418Whedon, J.M. Song, Y. Mackenzie, T.A.

Risk of Stroke After Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation in

Medicare B Beneficiaries Aged 66 to 99 Years With Neck Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015 (Feb); 38 (2): 93–101Choudry, E. Rofé, K.L. Konnyu, K.

Treatment patterns and population characteristics of

nonpharmacological management of chronic pain

in the United States’ Medicare population:

a scoping review

Innov Aging. 2023; 7:igad085Whedon, J. Kizhakkeveettil, A. Toler, A.

Initial choice of spinal manipulative therapy for treatment of chronic

low back pain leads to reduced long-term risk of adverse

drug events among older Medicare beneficiaries

Spine. 2021; 19, 0000000000004078Anderson, B. MacKenzie, T. Lurie, J.

Patterns of Initial Treatment and Subsequent Care

Escalation Among Nedicare Beneficiaries with

Neck Pain: A Retrospective Cohort Study

European Spine J 2025 (Feb); 34 (2): 724–730Anderson, B.R. MacKenzie, T.A. Grout, L.M.

Comparative Cost Analysis of Neck Pain Treatments

for Medicare Beneficiaries

Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2025 (Feb 14): 801-804Budnitz, D. Shehab, N. Lovegrove, M.

US emergency department visits attributed to medication harms, 2017-2019

JAMA. 2021; 326:1299-1309U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

National Action Plan for Adverse Drug Event Prevention

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (2014)Gurwitz, J. Field, T. Harrold, L.

Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events

among older persons in the ambulatory setting

JAMA. 2003; 289:1107-1116Zazzara, M. Palmer, K. Vetrano, D.

Adverse drug reactions in older adults:

a narrative review of the literature

Eur Geriatr Med. 2021; 12:463-473Gray, S. Perera, S. Soverns, T.

Systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions to

reduce adverse drug reactions in older adults: an update

Drugs Aging. 2023; 40:965-979Lee, V. Brown, Jr., R. Mandrekar, J.

Incidence and outcome of cervical artery dissection:

a population-based study

Neurology. 2006; 67:1809-1812Whedon, J. Song, Y. Mackenzie, T.

Risk of Stroke After Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation in Medicare B

Beneficiaries Aged 66 to 99 Years With Neck Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015 (Feb); 38 (2): 93–101Whedon, J. Petersen, C. Li, Z.

Association Between Cervical Artery Dissection and Spinal

Manipulative Therapy - A Medicare Claims Analysis

BMC Geriatrics 2022 (Nov 29); 22 (1): 917Whedon, J. Mackenzie, T. Phillips, R.

Risk of Traumatic Injury Associated with Chiropractic Spinal

Manipulation in Medicare Part B Beneficiaries Aged 66-99

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2015 (Feb 15); 40 (4): 264–270Whedon, J. Goertz, C. Lurie, J.

Beyond Spinal Manipulation: Should Medicare Expand Coverage

for Chiropractic Services? A Review and Commentary on

the Challenges for Policy Makers

J Chiropractic Humanities 2013 (Aug 28); 20 (1): 9–18Coulter, I. Crawford, C. Vernon, H.

Manipulation and Mobilization for Treating Chronic

Nonspecific Neck Pain: A Systematic Review and

Meta-Analysis for an Appropriateness Panel

Pain Physician. 2019 (Mar); 22 (2): E55–E70Weeks, W.B. Whedon, J.M. Toler, A.

Medicare's Demonstration of Expanded Coverage for

Chiropractic Services: Limitations of the

Demonstration and an Alternative

Direct Cost Estimate

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2013; 36:468-481.H.R.539 - 119th Congress (2025-2026)

Chiropractic Medicare Coverage Modernization Act of 2025

Return to CHRONIC NECK PAIN

Return to COST-EFFECTIVENESS

Since 9-15-2025

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |