Conceptualizing Clinical Expertise in Evidence-based

Practice: A Narrative Literature Review With

Implications for Clinical Decision-making

This section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Can Chiropr Assoc 2025 (Nov); 69 (3): 255-272 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Deborah Kopansky-Giles, BPHE, DC, FCCS, MSc1, • Jonathan Murray, BSc, MSc • Jessica M. Parish, BA (Hons), MA, PhD • Rod Overton, BSc, DC • Anita Chopra, BA, DC • Glen H. Harris, BSc, DC, FRCCSS(C) • Adrienne Shnier, MA, PhD, JD

Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College,

Department of Research and Innovation,

Toronto, ON

Objective: This review aimed to explore clinical expertise within evidence-based practice (EBP) by examining contemporary definitions of clinical expertise, how it can be acquired and developed over time, and its role within EBP.

Methods: PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus databases were searched for literature on clinical expertise published between January 2016 and August 2024. Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance. Full-text review was conducted for papers deemed potentially relevant.

Results: 23 articles were included in this review. Clinical expertise receives different treatments across literature. However, a commonality is that clinical expertise requires proficiency, skill, and clinical judgement that can be acquired only through clinical experience, collaboration, and hands-on clinical practice. Operating within Haynes' model of EBP, clinical expertise is central to integrating patient preferences and bridging the gap between standardized objective evidence and personalized care.

Conclusions: Clinical expertise represents the core of integrating EBP to inform clinical decision-making and is developed through experience and keeping current with research.

Author’s note: This paper is one of seven in a series exploring contemporary perspectives on the application of the evidence-based framework in chiropractic care. The Evidence Based Chiropractic Care (EBCC) initiative aims to support chiropractors in their delivery of optimal patient-centred care. We encourage readers to review all papers in the series.

Keywords: chiropractic; clinical competence; clinical skills; evidence-based medicine; evidence-based practice; professional competence.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

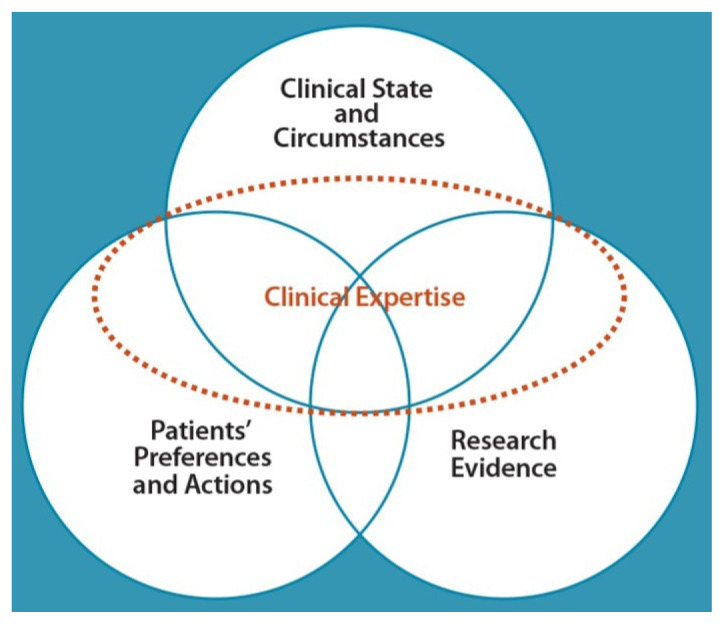

Figure 1 Clinical expertise is a central component of evidence-based practice (EBP), initially introduced within Sackett et al.’s evidence-based medicine model1 and later refined by Haynes et al. in their constructive engagement with this model. [2] In Haynes et al.’s enhanced and prescriptive model, clinical expertise expands across, informs, balances, and integrates the three components of evidence-based clinical decision-making: clinical state and circumstances, patients’ preferences and actions, and research evidence (Figure 1). [2] By emphasizing the central role of clinical expertise in EBP, the Haynes model provides a comprehensive and practical framework for examining clinical expertise further.

Clinical expertise is considered to be a lifelong learning process wherein clinicians amass primary knowledge over the course of their clinical interactions, as opposed to knowledge only gained from journal articles, randomized control trial (RCT) findings, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, or explicit medical education. [3–5] Clinical expertise is also considered to comprise many components including formal education in the field, multiple years of clinical experience, advanced credentials, visibility in the professional community, and demonstration of superior skill in practice. These components contribute to a clinician’s ability to provide EBP informed by the best relevant research, patient preferences and characteristics, and context of the problem. Clinical expertise draws together these components, guiding case formulation, clinical assessment, and clinical decision-making. [6]

Despite increasing recognition of the central role of clinical expertise in EBP, [4–7] the evidence pyramid continues to be heavily relied upon within research and training as a guide for determining the quality and usefulness of scientific evidence. In this model, ‘expert opinion’ is traditionally placed at the bottom of the pyramid, with observational studies, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs positioned above. [5] While the pyramid highlights the strengths of systematic research, its rigid hierarchy and lack of consideration of clinical expertise warrants reconsideration. For instance, the ‘gold standard’ in scientific evidence, RCTs, are not always attainable, may lack external validity, and can be difficult to apply in practice. [9]

Potential bias within RCTs is also not always easily identifiable, [9] requiring expertise to interpret findings within context. The usefulness of the evidence pyramid must be understood within the broader Haynes model, recognizing that clinical expertise and informed judgement are essential for assessing and applying evidence in practice. Clinical expertise, developed over time, is required to understand and appreciate practical consequences of bias within scientific literature, to unpack and apply trial results in an informed and contextualized manner. [10] Ultimately, clinical expertise is essential for interpreting and applying research findings to balance the evidence with individual patient circumstances and preferences, regardless of the state of evidence.

While its importance is recognized, clinical expertise remains poorly defined beyond its limited consideration in the evidence pyramid, creating challenges for chiropractic clinicians, educators, and researchers in fully integrating it into EBP. Accrediting chiropractic bodies and regulatory boards endorse EBP principles, yet a clear framework for conceptualizing, developing, and applying clinical expertise within EBP is lacking. [11, 12] Given the growing expectation for chiropractors and other healthcare professionals to incorporate EBP into practice, refining the discussion on clinical expertise is essential. Following Haynes’ EBP mode [1, 2] clinical expertise should not be seen as a standalone form of evidence to be placed on an evidence pyramid, but as a crucial mechanism for effectively applying research to patient care. [5]

As noted by Haynes et al., “evidence does not make decisions, people do”. [13] Clearly defining clinical expertise, examining how it can be acquired and developed by clinicians, and elucidating its pivotal role in guiding EBP will help overcome barriers to applying research and integrating all pillars of EBP in clinical decision-making.

This review aims to provide contemporary insight on the Haynes model’s conceptualization of clinical expertise and further refine its practicality, [2] providing clinicians withi) an enhanced definition of clinical expertise in an EBP context,

ii) how clinical expertise can be acquired and developed over time, and

iii) how clinical expertise operates within the Haynes model of EBP.This analysis is timely, given the development of updated clinical competencies in chiropractic education, and the expectation of accrediting bodies and regulatory boards for chiropractors and other health professionals to endorse EBP throughout their professional careers. [11, 12, 14]

Methods

Study design

We conducted a narrative review [15] of the literature to summarize contemporary definitions of clinical expertise, how clinical expertise is acquired and developed over time, and how it operates within the Haynes EBP model. [2] The narrative review method is appropriate in instances such as this, where the aim is to research a broad topic which has been studied and conceptualized differently across disciplines and traditions. [16]

Data sources and searches

The literature search for this review sought English-language peer-reviewed research articles published between January 1, 2016 and August 1, 2024 within PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus databases. The search was restricted to 2016 and onward to focus on providing a comprehensive understanding on recent perspectives of clinical expertise. We employed a range of search terms to achieve our objectives and capture relevant literature on clinical expertise (Appendix 1).

Selection criteria

We included empirical research articles as well as secondary sources of evidence (e.g., systematic, scoping, or narrative reviews, and commentaries), that substantively explored, described and considered clinical expertise within the context of EBP or evidence-based medicine (EBM), published between 2016 and 2024. We did not exclude articles based on country of origin. We excluded conference abstracts, protocols, and articles that lacked substantive exploration of clinical expertise within an EBP or EBM context.

Screening process

One author assessed titles and abstracts of articles returned in the search of each database to determine eligibility. Articles deemed potentially relevant underwent full-text review by the same author, considering each articles’ potential contribution to our exploration of clinical expertise within EBP/EBM. The rest of the working group confirmed inclusion of each full-text article.

Data extraction

Descriptive information was extracted from each article deemed relevant after full-text review, including first author, title, discipline, and information pertaining to exploring or analyzing clinical expertise, specifically within the context of EBP.

For this last item, data from each paper were grouped into one of three categories:(1) defining clinical expertise;

(2) acquiring and developing clinical expertise; and

(3) clinical expertise operating within EBP.These categories were determined a priori, in line with the purposes of our review. Themes within the extracted data corresponding to each of these categories were then determined iteratively. Data was extracted and summarized into a table by one reviewer. The data extraction table underwent independent review among the full working group, and required unanimous consensus among the full group.

Results

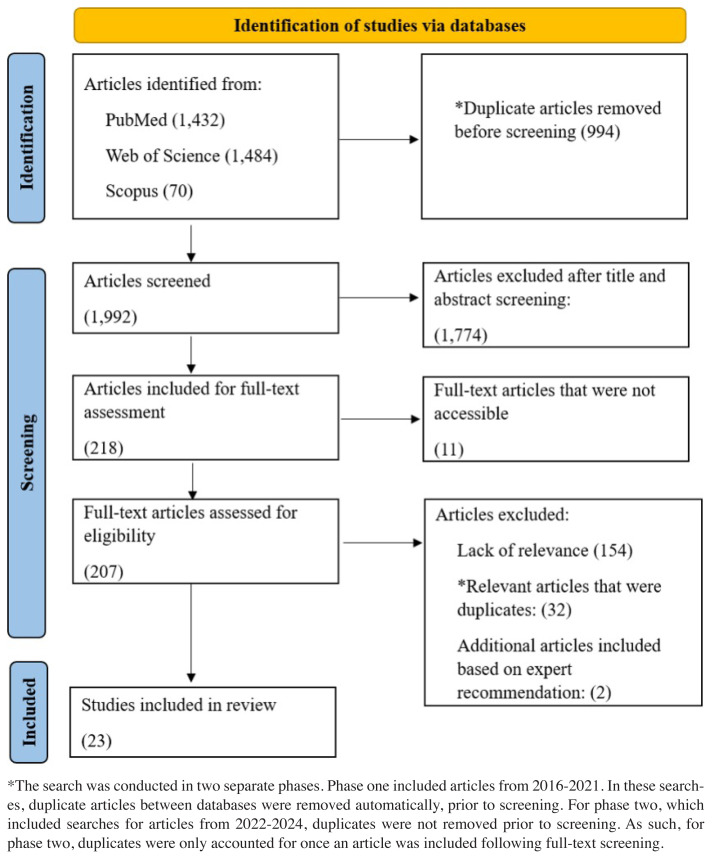

Figure 2

Table 1 The search identified 1,992 articles to be screened from PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus. The flowchart outlining article identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion is shown in Figure 2. Each of the 23 articles that met the inclusion criteria defined and/or analyzed the concept of clinical expertise in the context of EBM or EBP in health fields, which included

medicine (11 studies), [4, 7, 17–25]

nursing (2 studies), [26, 27]

occupational and physical therapy (4 studies), [28–31]

chiropractic (1 study), [32]

rehabilitation education (1 study), [33]

psychotherapy (1 study), [34]

speech-language therapy (2 studies), [35, 36] and

nutrition (1 study), [37] as shown in Table 1.

Identifying themes

Three central themes emerged from the literature in line with the three review objectives:(1) clinical expertise within EBP is the integration of clinical reasoning, experience, and evidence-based skills, guiding person-centred decision-making in healthcare,

(2) clinical expertise is acquired through collaboration, reflective practice, hands-on experience, and continuous learning over time, and

(3) clinical expertise acts as a mechanism of integrating evidence with patient-specific factors, guiding clinical decisions.Clinical expertise is the integration of clinical reasoning,

experience, and evidence-based skills

Clinical expertise has been defined in relation to the EBP model, as a necessary part of decision-making and central to the integration of best available evidence in practice. [34] Clinical expertise in the field of occupational therapy and allied health professions has been defined as “the habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values and reflection in daily practice”. [28] Expertise is considered to be more than “just time in practice,” since it involves the integration of clinical or professional reasoning, EBP, and assessing and measuring outcomes. [28] Importantly, clinical expertise is central to guiding clinical practice since not every clinical question has directly relatable or available data, requiring experience-informed decision-making. [20, 22, 34] Expertise is complex, requiring the explicit integration of best external research evidence into clinical practice, reflecting critically on practice, seeking and discussing experiences with colleagues, and reflecting on one’s own knowledge, beliefs, and values. [28] This complexity of expertise is evident within ‘paradoxes’ of evidence-based care, in which clinicians are responsible for navigating the balance between the standardization of guidelines and both clinician and patient autonomy to integrate individual patient preferences into a clinical decision. [18]

A qualitative analysis of expertise in the occupational therapy field defined two categories of expertise: expert evidence-based and outstanding occupational therapists. [29] In both categories, expertise was attributed to clinician dedication and motivation to learn, achieving great patient outcomes, and working in a specialized setting. [29] Expert evidence-based clinicians had extensive knowledge, skills, and experience, were engaged in professional development and knowledge translation. [29] Outstanding therapists had specialized experience, exceptional skills, professional competencies, and served as role models, mentors, and advocates, with strong client-centred approaches and collaboration. [29]

In this way, clinical expertise is recognized for its important role in informing clinical decision-making based on critical appraisal of evidence and patient values and preferences, rather than on external evidence alone, which may be inapplicable or inappropriate for an individual patient. [21, 27] This is reflected in the “Architect Analogy of EBP”, in which Paez describes clinical expertise as consisting of three overlapping skill sets: clinical, technical, and organizational. [7]The clinical component involves communication skills and knowledge and experience with patient engagement,

the technical component involves skills in forming questions and appraising and applying evidence in clinical practice, and

the organizational component covers skills within interdisciplinary teamwork. [7]Paez notes that together, these elements of expertise complement evidence-based practice (EBP) by structuring and enhancing clinical decision-making, rather than serving as evidence themselves. [7]

Clinical expertise is also defined as being derived from primary experience and being necessary for ideal clinical practice. [4] Primary experience has value and knowledge utility that is central to clinical practice in order for a clinician to possess the experiential knowledge required to diagnose, treat, and assess individual patients. [4] Reliance on clinician experience through hands-on practice and engagement with patients and colleagues leads to a development of iterative, experiential knowledge on which clinicians rely each day in practice. [4] A critical element of achieving expert status is accumulating the vast hands-on experience that enables those experts to recognize patterns in diagnosis and treatment effortlessly most of the time and to recognize when signs and symptoms fail to fit that pattern, requiring alternate action, such as referral to other professionals. [4, 18]

Conversely, a survey analysis in the discipline of speech-language pathology defined professional expertise with the objective of assisting healthcare organizations in developing expectations of their professionals, highlighting that measuring years of experience alone is not sufficient to inform expertise. [35] Rather, Jackson et al. argue an evolved shift in the understanding of clinical expertise requires viewing expertise as a quality that is possessed by an individual clinician and is perceived as such by those who bear witness to the clinician’s behaviours and practice. [35]

An interview study with oncologists added that because clinical expertise involves a complex integration of many interrelated factors, it cannot be fully appreciated using quantitative measures alone. [24] For example, factors such as non-explicit knowledge and implicit biases were mentioned to not be captured through quantitative measures of clinical expertise, yet play a crucial role in informing a clinician’s expertise. [24] Still, the importance of considering experience when informing expertise is not debated, as Salloch et al. found that two dimensions of clinical experience (direct patient contact on an individual basis and having treated many patients over the course of one’s career) contributed to one’s level of clinical expertise in this interview-based study. [24]

Comparatively, studies originating from Sweden emphasized the continuation of a century-long history of vetenskap och beprövad erfarenhet (VBE), recognizing the importance of clinical expertise and judgement in healthcare. [19, 26] The centrality of the role of VBE in Swedish healthcare is illustrated by Sweden’s legal regulation of healthcare, which requires VBE, best translated as ‘science and proven experience.’ VBE is considered to be the gold standard in decision-making practice in Sweden, though it has not been well-defined in the literature. [19, 26]

The concept of VBE extends beyond the concept of ‘clinical expertise’ and can function as a stand-alone construct, independent from clinical expertise. In this regard, EBM is considered a reformulation of the Swedish standard. [19] This notion of VBE has been required by law in Sweden since 1981 and has been engrained into the training of all clinicians. This has resulted in Swedish clinicians having a good understanding of the role and nature of clinical experience and judgement, balanced by knowledge gained through research. [19, 26] The Swedish model of ‘proven experience’ allows for a more explicit understanding of the integration of evidence into practice and conceptualization of the role of evidence in practice. [26]

A key concept within VBE is ‘proven experience’, which refers to the quality or characteristic of being experienced or possessing experience, rather than to describe the content of the experience. [26] The concept of proven experience is aligned with clinical expertise in EBP, and it is a trait to be acquired by clinicians throughout their clinical careers. [26] VBE promotes more reflective analysis by clinicians by informing their applications of relevant evidence to their patients’ clinical circumstances. [26] Where the EBM model may be interpreted as casting a hierarchy over various kinds of scientific evidence, the VBE model regards good decision-making as considering both science and proven experience, together. [19] Although the Swedish concept of ‘science and proven experience’ has clear parallels with characteristics of the EBM model, VBE offers additional clarity in terms of the epistemological role of expertise and clinical judgement.

Clinical expertise is acquired through collaboration,

reflective practice, hands-on experience, and

continuous learning over time

Experience on its own is reflected across multiple disciplines as being important to developing clinical expertise. [4, 31, 34] Within medicine, it is suggested that primary experience, such as diagnosis, treating, and assessing individual patients, facilitates development of experiential knowledge of care and patient engagement, which is necessary in practice. [4] In psychotherapy, a survey analysis highlighted how effectively using external evidence in case formulations (the process of integrating theory to a particular case) is a clinical skill that is developed through experience. [34]

Despite the importance of experience in the development of clinician expertise, a speech language therapy study argued that practice alone did not equate to highly proficient clinicians. [35, 36] Douglas et al. suggest that length of time in practice does not necessarily result in a higher level of clinical expertise as many senior clinicians maintain practice patterns related to habit rather than integrating new knowledge on an iterative basis. [36] Several key elements to impact and support the development of clinical expertise were identified by Douglas et al., including: training; individual clinician traits and actions; work sites; having a holistic view versus disorder-specific view; professional networking; peer and patient recognition; embracing the creative/mysterious; technical excellence and acknowledgment of and learning from one’s own mistakes. [36]

Clinical expertise also requires the continued development of “habits of mind,” suggesting the importance of participating in activities that foster critical clinical reasoning and reflection to improve clinicians’ clinical expertise. [28] This may include engaging in “learning conversations”, described in a study that interviewed general practitioners. Authors found that “learning conversations” were important tools for learning and discussing the implementation and practice of EBM for general medical practitioners. [23] Learning conversations were defined as discussions that focused on a medical topic or question in which those engaged had no specific instructions on how to do so. [23]

Within these discussions, practitioners reflect on medical cases or topics that are of relevance to their daily practice. [23] Respectful, learning conversations were found to be especially important elements in peer-to-peer communication, interprofessional collaboration, and in training or mentorship of new practitioners. [23] A cross-sectional study within rehabilitation education highlighted how institutions can help with facilitating learning conversations, and as a result, promote clinical expertise development. [33] Such support may come from regulatory bodies, associations, or educational institutions, and include educational and research opportunities, as well as resources and accessible research. [33]

Supporting the importance of collaboration in professional skill development, Carr et al. described a three-staged cyclical process to support the advancement of clinical expertise using a mentor-learner model. [30] The sequential phases included: ‘requirements prior to learning activity’ (a self-reflection), the ‘learning activity’ (observing clinical practice), and ‘collaborative reflection and analysis’ (reflection on the experience, also known as professional craft knowledge). [30] Utilization of this phased approach was considered to facilitate effective development of clinical expertise. [30]

Characteristics such as humility, conscientiousness, curiosity, open-mindedness, and leadership were noted by occupational therapists as essential to developing expertise. [31] Specifically, expertise required the ability to be adaptable in practice, in addition to deliberate, motivated effort to continuously grow and improve oneself professionally. [29, 31] Motivators to achieve expertise may include a desire to achieve better patient outcomes, the recognition of ethical obligations, or a defining moment in a clinician’s career that made them recognize they could achieve a higher level. [31]

Students acting as mentors by bringing new knowledge into clinics can also serve as motivators to developing expertise. [31] The strengthening of innate characteristics, such as compassion and other soft skills, and the continued humble recognition of gaps in a clinician’s knowledge, coupled with the desire for continued learning beyond a clinician’s current state of knowledge, further contributes to developing adaptive expertise. [29, 31] This strengthening requires support through education, knowledge translation and research opportunities, and hands-on clinical practice. [29] Expertise is then evidenced by advanced educational credentials, pedagogical, ethical, and cultural competence, personal interaction, professional conduct, cooperation and network competence, as well as knowledge of administrative and occupational well-being. [33, 34]

Clinical expertise acts as a mechanism of integrating

evidence with patient-specific factors

While some current literature considers the updated Haynes model of EBP (Figure 1), [7, 19, 21] other contemporary literature and regulatory bodies rely on the older EBP model for its evidence hierarchy and differential attribution of value and weight to various knowledge sources. [21, 27] Institutions often prioritize clinical data through a strict ranking system, treating RCTs as the gold standard while considering other forms of evidence as inferior. [21] While RCTs are indeed the gold standard, effective clinical decision-making requires more than simply following study outcomes – it necessitates the integration of clinical expertise to apply evidence in a way that aligns with individual patient needs. [17, 20–22, 25]

Clinical expertise is not an alternative to research evidence, [5] but rather a dynamic mechanism that balances a patient’s clinical state and circumstances, relevant research, and the patient’s preferences and actions. [17, 21, 22, 37] It remains essential whether strong research evidence is available or lacking. For example, when RCT results are not applicable to a particular patient due to study design limitations (e.g., restricted inclusion criteria), clinical expertise is necessary to assess other relevant research, evaluate potential risks, and incorporate patient preferences. [21, 22] In this case, RCTs would be the gold standard for the demographic their study included, but clinical expertise ensures the evidence is interpreted and applied appropriately for each individual case. [21, 22] Importantly, clinical expertise should not be conflated with expert opinion, [5] which represents a static form of evidence that may not account for patient-specific factors.

In a commentary, Szajewska suggests there is an overwhelming amount of clinical research, much of which is low quality due to poor design, being statistically underpowered, and over reliance on p-values, leading to potentially incomplete or false conclusions. [22] In a study of RCT results for treating eating disorders Peterson et al. add the complexity of applying inconsistent study results. [20] Specifically, diverse patient profiles such as comorbidities, age, and cultural context complicate treatment and evidence selection, making expert judgement crucial in caring for each individual patient. [20]

Two additional commentaries also raise concerns about the lack of ability of RCTs and systematic reviews to inform treatment in multi-morbid patients, arguing that a transition to protocol-driven care limits clinician judgement and patient autonomy, when treating such patients. [17, 25] While the importance of research is never debated, authors suggest that the over-reliance on systematic research alone neglects the other pillars of EBP, leading to care that may not be optimal. [17, 25]

Van de Vliet et al. emphasize this does not diminish the role of research in patient care as neglecting any pillar within EBP poses a risk, including disregarding patient values leading to overly rigid care, ignoring research evidence resulting in outdated treatments, or overlooking clinical expertise potentially exposing a patient to inappropriate treatment. [17] Clinical care therefore relies on a clinician’s ability to effectively appraise, interpret, and apply the research, as opposed to adhering to strict guidelines and overlooking the nuances of clinical practice. [17, 20, 22, 25]

Through a similar consideration of the value of clinical expertise, Paez explicitly and purposefully situates clinician expertise at the centre of EBP in their model, together with the clinical question/patient problem. [7] This positions the clinician as the “architect” or creator of the clinical path forward for the patient. [7] Paez views the clinician’s role as important in framing clinical questions, assessing the evidence, and, ultimately, influencing patients’ lives and the generation of evidence through practice; in turn, creating new research questions and identifying new needs for evidence. [7] These clinician responsibilities across all disciplines reflects the importance of clinical judgement and iterative decision-making processes in evaluating the merits and appropriateness of evidence-based interventions on the health and wellbeing of patients. [7, 19, 26, 37]

An interview analysis with chiropractic trainees and patients highlighted the importance of the clinician-patient relationship for optimal care. [32] Patients valued clear explanations from their chiropractor which helped them understand the cause of their issue and what they needed to do to help themselves improve. [32] It was the patients’ confidence in their chiropractor’s expertise that developed a bond and facilitated progress with treatment goals. [32] Thorough initial assessments and confidence of the chiropractor contributed to a strong patient-provider relationship, emphasizing the importance of expertise acting as a mechanism of integration within chiropractic care. [32]

Discussion

In this review we aimed to synthesize contemporary literature providing insight on a definition of clinical expertise, how clinical expertise can be acquired and developed, and how clinical expertise operates within EBP. Three key themes emerged, each addressing our main objectives.

First, clinical expertise is recognized as a dynamic integration of clinical reasoning, experience, and evidence-based skills, crucial for personalized healthcare decisions.

Second, clinical expertise is developed through a combination of reflective practice, collaboration, handson experience, and continuous learning.

Finally, clinical expertise serves as a mechanism for synthesizing evidence with patient-specific factors, ensuring that clinical decisions are not solely dictated by research evidence but are instead a balanced integration of all three other pillars of EBP: best available evidence, clinical state and circumstances, and patient preferences. These findings underscore the multifaceted nature of clinical expertise, as it intertwines professional experience with EBP.

The concept of clinical expertise does not have a standardized, uniform definition; rather, clinical expertise is a dynamic concept that continues to evolve over time. [5] While clinical expertise has received different definitions and treatments across studies, common among the literature is that clinical expertise requires proficiency, skill, and clinical judgement that can be acquired only through clinical experience, collaboration, and hands-on clinical practice. [5, 7, 18, 35, 38]

Clinical expertise is not static however, as it must continuously evolve alongside advancements in research and changes in patient needs, reinforcing its essential role in bridging the gap between evidence and personalized care. The Swedish concept of VBE contributes an evolved understanding and expanded definition of clinical expertise as a concept that has value for not only individual clinicians, but also their patients and the institutions within which they work. [19, 26] A more clarified, nuanced, and holistic perspective on clinical expertise, such as the one provided here, allows clinicians to not only strive for professional growth, but also understand the goalposts.

The traditional EBM evidence hierarchy inherently considers clinical expertise as a form of knowledge or method of knowing that is independent of, and potentially inferior to, the classic evidence pyramid. [5] The placement of expert opinion at the bottom of the evidence pyramid has a mixed legacy. On the one hand, it may correctly signal that research questions can and should be informed by clinical experience and observation. On the other hand, this has been traditionally and wrongfully interpreted to imply that clinical expertise is wholly internal to evidence and, as such, is comparable and subordinate to research evidence.

The latter view conflates the role of clinical expertise within research with clinical expertise in the context of delivering patient care. While related, these contexts are distinct and should be explicitly acknowledged as such. Specifically, expert opinion represents a static form of evidence that may not account for patient-specific factors, unlike clinical expertise which dynamically integrates research evidence, a patient’s clinical state and circumstances, and their preferences to guide personalized decision-making.

Regardless of whether clinical expertise should be considered as internal or external to the evidence pyramid, authors in the reviewed literature argue the evidence hierarchy cannot be used alone in guiding clinical practice. [4, 7, 17, 20–22, 25] The clinician needs to appropriately integrate evidence with patient preferences and their own experience into their decision-making. [4, 7, 17, 20–22, 25] However, these authors suggest the emergence of EBP and this evidence hierarchy has led some to rely exclusively on “objective” evidence, thereby presenting challenges when specific individual patients don’t ‘fit’ within the proposed care plans. [7, 17, 20–22, 25]

While these views largely come from commentary papers, and are therefore essentially opinions, the value in these points should not be dismissed. An overreliance on systematic data does threaten a lack of consideration of patient preferences and clinical judgement. On the other hand, the value of research should also never be diminished either. Therefore, a non-hierarchical understanding of clinical knowledge and clinical judgement contributes to more well-rounded, collaborative, and customized clinical care. [4] Particularly, one that recognizes clinical expertise as the central mechanism through which the three EBP pillars – evidence, clinical circumstances, and patient preferences – are meaningfully combined in real-world decision-making.

The Haynes model of EBP advances this perception of clinical expertise to one that overlays and integrates their modified factors of clinical state and circumstance, patients’ preferences and actions, and research evidence (Figure 1). [2] Clinical expertise must, therefore, be considered as a complementary and informative form of knowledge, since the clinician must use their clinical skill, judgement, and experience to understand and interpret systematic reviews and trials, and then apply (or hold) treatment, as appropriate.

This is instead of ranking clinical expertise on a scale of actual evidence, and inferior to published data. Clearly, individual clinical expertise is formed, evolves over time, and is built on a strong foundation of clinical practice, skill, judgement, collaboration, active involvement in teaching and research to advance the clinician’s field and advocate for advancement.

The integration of the three components of EBP in the Haynes model relies on the application of clinical expertise inherently, as part of practice. [2] For instance, the component of clinical state and circumstances requires clinical expertise to not only understand, but also parse the structural determinants – social, political, economic – of health, as well as personal, individualized constraints and factors arising from physiological, emotional, and psychological circumstances. [2, 26] A clinician’s expertise will guide their implementation and continued assessment of a proposed therapeutic plan that accounts for these circumstances. Without an educated, experience-based assessment of these structural and individual determinants, proposed treatment plans may be too costly, burdensome, or stressful, leading to reduced compliance.

Akin to the clinical state and circumstances component, the patient values and preferences component requires an informed and aware attention to, and accounting for, diversity, equity, and inclusion, as well as the power differential between clinicians and their patients, when proposing and prescribing therapeutic interventions. A clinician’s consideration of these factors requires effective and thoughtful communication and observational skills, important elements of expertise. [7, 28, 37] Patient preference may, at times, conflict with research evidence and a clinician’s compass based on their experience. In these instances, clinicians should be guided by principles of informed consent, shared decision-making, ethics, and their fiduciary duties to the patient. [39]

Their clinical expertise should also serve as a reliable guide on which they can rely for strategies to navigate these circumstances. [7] This reinforces the role of clinical expertise as a dynamic, applied skill set – one that allows clinicians to negotiate complex, sometimes conflicting, elements of patient care while ensuring decisions remain grounded in ethical, evidence-informed practice. [3, 7, 39] The model of EBP in a context of caring provides another framework for understanding the integrated role of clinical expertise and reliance on the clinician for their assessment of the patient and their circumstances, preferences, and values, along-side research evidence. [40]

Clinical expertise is a lifelong journey that begins, and continues to develop, with training, education, and practice. [3] Beginning with basic training through formal education, accreditation, and licensure as regulated health professionals, clinicians such as chiropractors begin to develop the core competencies that form the foundation for their clinical expertise. In Canada, for instance, chiropractors develop seven areas of competency:(1) expertise in neuromusculoskeletal (nMSK) health, including differential diagnoses, evidence-based patient-centred management, and diagnostic procedures and therapeutic interventions,

(2) clear, responsible communication, including informed consent,

(3) skillful collaboration with inter- and intra-professional practitioners,

(4) advocacy for health, safety, and quality of life,

(5) application of EBP in patient-centred care,

(6) professionalism, including ethical skill, cultural sensitivity, and self-reflection, and

(7) leadership to improve healthcare delivery and professional development. [11, 12]The Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College (CMCC) [11] and the Federation of Canadian Chiropractic (FCC) [12] adapted the CanMEDS Framework [14] of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, in which the clinical expert is positioned at the centre of the competencies, illustrating the multitude of roles that the clinical expert endeavors to master. Contributing to clinical expertise, these competencies deepen and develop through continuing chiropractic education and rigorous clinical practice including ongoing evaluation of a patient’s condition, progress and intervention effectiveness, and ongoing discussion with the patient regarding the patient’s goals and expectations for their ongoing care. [41]

In accordance with the literature, chiropractic expertise develops and evolves over time and with ongoing participation in opportunities for collaboration, conversation, keeping up-to-date on developments in knowledge (which tends to decline following graduation), as well as hands-on clinical practice. [6, 42] The iterative development of chiropractic clinical expertise is well-suited to adopt and enact EBP also through mentorship and open learning conversations, participating in research and conferences, continuing education, collaboration, contribution to learning, and participation in advancement of the field. [35, 43] As a regulated health profession, the institutions that support the professional development of chiropractors should continue to provide opportunities for deepening and optimizing each of the factors that contribute to a comprehensive foundation for clinicians to develop their clinical expertise.

The value of clinical expertise to clinicians, their patients, their communities, and health institutions cannot be understated. It is a continuously evolving skill set that ensures evidence-based care remains patient-centred, adaptable, and contextually relevant. As such, it is imperative for all clinicians to commit to lifelong learning and for institutions to provide sustained support for their ongoing professional development.

Limitations

This narrative review had the following limitations. Firstly, restricting the search to English-only articles published after 2016 excluded potentially relevant papers published prior to 2016 that could have offered insights into clinical expertise. Secondly, certain fields of study may have been excluded by exclusively relying on articles from three databases, including potentially valuable narrative or anecdotal evidence that may not have been considered. Moreover, we did not use a systematic search strategy or conduct formal risk of bias assessments, as the goal was to broadly cover the healthcare landscape capturing literature that explored clinical expertise from multiple disciplines.

This flexibility facilitated the integration of diverse sources and insight on clinical expertise in EBP. Additionally, only one reviewer conducted screening and data extraction, which introduces an inherent degree of subjectivity in thematic synthesis and categorization, particularly on a topic that already has subjectivity around it. This limitation was mitigated by having the full working group review inclusion of papers and data extraction from included studies.

Lastly, no interviews were conducted in this review, so clinicians’ contemporary attitudes and perspectives concerning our construction of clinical expertise and how clinicians can acquire it require further research.

Conclusion

This narrative review has described current definitions of clinical expertise and illustrated it within Haynes’ model of EBP. Three key themes emerged from the literature:(1) clinical expertise integrates reasoning, experience, and evidence-based skills for person-centred care;

(2) it is acquired through collaboration, reflection, experience, and continuous learning; and

(3) it serves as a mechanism for integrating research evidence with patient-specific factors to inform clinical decisions.This review provides examples of how clinical expertise can be developed and maintained over time and the importance of ongoing participation in a clinician’s profession to realize the status of possessing and continually advancing clinical expertise. It highlights that clinical expertise is a lifelong, dynamic, evolutionary process in which clinicians should engage throughout their professional careers. Newer approaches to EBP such as the Hayne’s model recognize that clinical expertise (developed through personal experience, keeping current with research and lifelong learning) is an important element in ensuring the delivery of quality care to patients.

Appendix 1. Search phrases

We used the key terms “clinical expertise”, “professional development”, “continuing education”, EBP, “evidence-based medicine (EBM)”, “competence”, “clinical judgment”, “experience”, “experiential knowledge”, “clinician communication”, “chiropractor/doctor-patient relationship”, “patient-centered care”, “skills development”, and “training”. These terms were utilized in the following phrases to conduct searches in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science: (1) “Clinical Expertise” and “evidence based medicine” or “evidence based practice” and “development” and “experience”, and “patient”

(2) “Clinical Expertise” AND “evidence-based medicine” OR “evidence-based practice” AND “clinical communication”,

(3) “Clinical Expertise” AND (“evidence-based medicine” OR “evidence-based practice”) AND “continuing education”,

(4) “Clinical Expertise” AND (“evidence-based medicine” OR “evidence-based practice”) AND “continuing medical education”,

(5) “Clinical Expertise” AND (“evidence-based medicine” OR “evidence-based practice”) AND “continuing professional development”,

(6) “Clinical Expertise” AND (“evidence-based medicine” OR “evidence-based practice”) AND “doctor patient relationship”,

(7) “Clinical Expertise” AND (“evidence-based medicine” OR “evidence-based practice”) AND “patient-centred care”,

(8) “Clinical Expertise” AND (“evidence-based medicine” OR “evidence-based practice”) AND “skills development”,

(9) “Clinical Expertise” AND (“evidence-based medicine” OR “evidence-based practice”) AND “clinical competence”,

(10) “Clinical Expertise” AND (“evidence-based medicine” OR “evidence-based practice”) AND “chiropractor patient relationship”,

(11) “clinical expertise” and “evidence-based medicine” or “Evidence-based practice” and “chiropractor patient relationship”,

(12) “Clinical Expertise” AND (“evidence-based medicine” OR “evidence-based practice”) AND “skills development” AND “training”,

(13) “Clinical Expertise” AND (“evidence-based medicine” OR “evidence-based practice”) AND “chiropractor”,

(14) “Clinical Expertise” AND (“evidence-based medicine” OR “evidence-based practice”) AND “regulated health care professional”,

(15) “Clinical Expertise” AND (“evidence-based medicine” OR “evidence-based practice”) AND “healthcare professional”,

(16) “Clinical Expertise” AND (“evidence-based medicine” OR “evidence-based practice”) AND “clinical judgement”,

(17) “Clinical Expertise” AND (“evidence-based medicine” OR “evidence-based practice”) AND “experiential knowledge”Acknowledgments

Thank you to Pegah Rahbar for her assistance in manuscript and referencing organization.

Conflicts of Interest:

This research was funded by the OCA. The lead authors received a per diem for their work on this project. The authors declare no other conflicts of interest, including no disclaimers, competing interests, or other sources of support or funding to report in the preparation of this manuscript.

References:

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Gray JAM, Haynes RB, Richardson WS.

Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t.

BMJ. 1996;312(7023) doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71.Haynes RB, Devereaux PJ, Guyatt GH.

Clinical expertise in the era of evidence-based

medicine and patient choice.

ACP J Club. 2002;136(2):A11–4.Johnson C.

Evidence-Based Practice in 5. Simple Steps

J Manip Physiol Ther. 2008;31L:169–170.

doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.03.013.Tonelli MR, Shapiro D.

Experiential knowledge in clinical medicine:

use and justification.

Theor Med Bioeth. 2020;41(2–3):67–82.

doi: 10.1007/s11017-020-09521-0.Wieten S.

Expertise in evidence-based medicine:

a tale of three models.

Philos Ethics, Humanit Med. 2018;13(1)

doi: 10.1186/s13010-018-0055-2.Overholser JC.

Clinical expertise: A preliminary attempt

to clarify its core elements.

J Contemp Psychother. 2010;40:131–139.Paez A.

The “architect analogy” of evidence-based practice:

Reconsidering the role of clinical expertise and

clinician experience in evidence-based health care.

J Evidence-Based Med. 2018;11:219–226.

doi: 10.1111/jebm.12321.Simon SD.

Is the randomized clinical trial the gold standard

of research? Andrology lab corner.

J Androl. 2001;22:938–943.

doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2001.tb03433.x.Nolet PS, Emary PC, Murray J, Harris G, Gleberzon B.

Conceptualizing the evidence pyramid for use in

clinical practice: a narrative literature review.

J Can Chiropr Assoc Forthcoming. 2025Mugerauer R.

Professional judgement in clinical practice (part 3):

A better alternative to strong evidence-based medicine.

J Eval Clin Pract. 2021;27(3):612–623.

doi: 10.1111/jep.13512.Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College (CMCC)

Doctor of Chiropractic Program Graduate Competencies. 2021Federation of Canadian Chiropractic.

Entry-to-Practice Compentency Profile for Chiropractors

in Canada. 2018.

https://chirofed.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/entry-to-

practice-competency-profile-DCP-Canada-Nov-9.pdfHaynes RB, Devereaux PJ, Guyatt GH.

Physicians’ and patients’ choices in evidence based practice.

Br Med J. 2002;324(7350):1350.

doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7350.1350.Frank JR, Snell L, Sherbino J, editors.

CanMEDS: Better standards, better physicians, better care.

CanMEDS Framework. 2015.

https://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/canmeds/canmeds-framework-eGreen BN, Johnson CD, Adams A.

Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed

journals: secrets of the trade.

J Chiropr Med. 2006;5(3):101–117.

doi: 10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60142-6.Grant MJ, Booth A.

A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14

review types and associated methodologies.

Health Info Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108.

doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.Van de Vliet P, Sprenger T, Kampers LFC, Makalowski J, et al.

The Application of Evidence-Based Medicine in

Individualized Medicine.

Biomedicines. 2023;11(7)

doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11071793.Issel LM.

Paradoxes of Practice Guidelines, Professional Expertise,

and Patient Centeredness: The Medical Care Triangle.

Med Care Res Rev. 2019;76:359–385.

doi: 10.1177/1077558718774905.Persson J, Vareman N, Wallin A, Wahlberg L, Sahlin NE.

Science and proven experience: a Swedish variety of

evidence-based medicine and a way to better risk analysis?

J Risk Res. 2019;22(7):833–843.Peterson CB, Becker CB, Treasure J, Shafran R.

The three-legged stool of evidence-based practice in

eating disorder treatment: Research, clinical,

and patient perspectives.

BMC Med. 2016;14(1)

doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0615-5.Schlegl E, Ducournau P, Ruof J.

Different Weights of the Evidence-Based Medicine Triad

in Regulatory, Health Technology Assessment, and

Clinical Decision Making.

Pharmaceut Med. 2017;31(4):213–216.

doi: 10.1007/s40290-017-0197-3Szajewska H.

Evidence-Based Medicine and Clinical Research:

Both Are Needed, Neither Is Perfect.

Ann Nutr Metab. 2018;72:13–23.

doi: 10.1159/000487375.Welink LS, Groot E, De Pype P, Van Roy K, et al.

GP trainees’ perceptions on learning EBM using

conversations in the workplace:

A video-stimulated interview study.

BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1)

doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02051-2.Salloch S, Otte I, Reinacher-Schick A, Vollmann J.

What does physicians’ clinical expertise contribute to

oncologic decision-making? A qualitative interview study.

J Eval Clin Pract. 2018;24(1):180–186.

doi: 10.1111/jep.12840.Ratnani I, Fatima S, Abid MM, Surani Z, Surani S.

Evidence-Based Medicine: History, Review,

Criticisms, and Pitfalls.

Cureus. 2023;15(2):e35266.

doi: 10.7759/cureus.35266.Dewitt B, Persson J, Wahlberg L, Wallin A.

The epistemic roles of clinical expertise:

An empirical study of how Swedish

healthcare professionals understand

proven experience.

PLoS One. 2021:16.

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252160.Teolis MG.

Improving Nurses’ Skills and Supporting a Culture

of Evidence-Based Practice.

Med Ref Serv Q. 2020;39(1):60–66.

doi: 10.1080/02763869.2020.1688626.Benfield AM, Johnston MV.

Initial development of a measure of evidence-informed

professional thinking.

Aust Occup Ther J. 2020;67(4):309–319.

doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12655.Hallé MC, Mylopoulos M, Rochette A, Vachon B, et al.

Attributes of evidence-based occupational therapists

in stroke rehabilitation.

Can J Occup Ther. 2018;85(5):351–364.

doi: 10.1177/0008417418802600.Carr M, Morris J, Kersten P.

Developing clinical expertise in musculoskeletal

physiotherapy; Using observed practice to

create a valued practice-based

collaborative learning cycle.

Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2020;50:102278.

doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2020.102278Thomas A, Amari F, Mylopoulos M, Vachon B.

Being and Becoming an Evidence-Based Practitioner:

Occupational Therapists’ Journey Toward Expertise.

Am J Occup Ther. 2023;77(5):7705205030.

doi: 10.5014/ajot.2023.050193.Ivanova D, Newell D, Field J, Bishop FL.

The development of working alliance in early stages

of care from the perspective of patients attending

a chiropractic teaching clinic.

Chiropr Man Therap. 2024;32(1):10.

doi: 10.1186/s12998-023-00527-8.Halvari J, Mikkonen K, Kääriäinen M, Kuivila H, et al.

Social, health and rehabilitation sector educators’

competence in evidence-based practice:

A cross-sectional study.

Nurs Open. 2021;8(6):3222–31.

doi: 10.1002/nop2.1035.Huisman P, Kangas M.

Evidence-Based Practices in Cognitive Behaviour

Therapy (CBT) Case Formulation: What Do

Practitioners Believe is Important,

and What Do They Do?

Behav Chang. 2018;35(1):1–21.Jackson BN, Purdy SC, Cooper-Thomas H.

Professional expertise amongst speech-language

therapists: “willing to share.”.

J Heal Organ Manag. 2017;31(6):614–629.

doi: 10.1108/JHOM-03-2017-0045.Douglas NF, Squires K, Hinckley J, Nakano EV.

Narratives of Expert Speech-Language Pathologists:

Defining Clinical Expertise and

Supporting Knowledge Transfer.

Teach Learn Commun Sci Disord. 2019;3(2):1.Johnston BC, Seivenpiper JL, Vernooij RWM, et al.

The Philosophy of Evidence-Based Principles and

Practice in Nutrition.

Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2019;3(2):189–199.

doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2019.02.005.Letterie G.

Three ways of knowing: the integration of clinical

expertise, evidence-based medicine, and artificial

intelligence in assisted reproductive technologies.

J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;38(7):1617–1625.

doi: 10.1007/s10815-021-02159-4.Alexopulos S, Cancelliere C, Côté P, Mior S.

Reconciling evidence and experience in the

context of evidence-based practice.

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2021;65(2):132.Fineout-Overholt E, Melnyk BM, Schultz A.

Transforming health care from the inside out:

Advancing evidence-based practice

in the 21st century.

J Prof Nurs. 2005;21(6):335–344.

doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.10.005.College of Chiropractors of Ontario.

Standard of Practice S-002 Record Keeping.

Standards of Practice. 2018.

https://cco.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/S-002.pdfAlbarqouni L, Hoffmann T, Straus S, Olsen NR, et al.

Core Competencies in Evidence-Based Practice for

Health Professionals: Consensus Statement

Based on a Systematic Review and Delphi Survey.

JAMA Netw open. 2018;1(2):e180281.

doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0281.Innes SI, Leboeuf-Yde C, Walker BF.

How comprehensively is evidence-based practice

represented in councils on chiropractic

education (CCE) educational standards:

A systematic audit.

Chiropr Man Ther. 2016;24(1)

doi: 10.1186/s12998-016-0112-0.

Return to EVIDENCE–BASED PRACTICE

Since 11-18-2025

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |