|

The Problem(s) with Randomized Controlled Trials and Meta Analyses

A Chiro.Org article collection

This group of articles reviews some of the difficulties designing randomized, placebo-controlled trials for chiropractic, and discusses the interpretive bias that has occurred when both the placebo and active SMT groups improved over baseline.

|

|

A Comprehensive Review of Chiropractic Research

Anthony Rosner, PhD, Research Director of FCER

Anthony Rosner, PhD, Research Director of FCER ~ FULL TEXT

“Evidence-based medicine” [EBM] was introduced as a term to denote the application of treatment that has been proven and tested “in a rigorous manner to the point of its becoming 'state of the art.'” [12] Its intention has been to ensure that the information upon which doctors and patients make their choices is of the highest possible standard. [13] To reach a clinical decision based upon the soundest scientific principles, EBM proposes five steps for the clinician to follow as shown in TABLE 2. [14]

|

|

Evidence-Based Medicine: Changing with the Tides

From ChiroACCESS (March 5, 2009) ~ FULL TEXT

Evidence-based medicine, to which all clinical researchers strive and all third party payors genuflect, is anything but the immutable Gold Standard of medical decision-making in recent years. Rather than being viewed as a Rock of Gibraltar, EBM almost appears more like a sand castle subject to the shifting sands of changing public sentiment as well as the updated scientific findings themselves.

|

|

Chiropractic Evidence Summary

Palmer College of Chiropractic (July 2018) ~ FULL TEXT

Evidence-based clinical practice (EBCP) is defined as “the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients.” [1] Increasingly, high-quality research evidence is the cornerstone to evidence-based healthcare decisions and is critically important to physicians, patients, policymakers and payers. This data-driven evolution will impact the chiropractic profession in important ways. It has the potential to serve as the play-field leveler that the chiropractic profession has long demanded. However, it also forces us to collect and interpret data correctly. This paper provides a very brief summary of the state of the evidence in chiropractic related to clinical outcomes, safety, cost and patient satisfaction.

|

Enhancing Evidence-based Chiropractic Practice

A 7–Study Series

|

The Ontario Chiropractic Association's Evidence-Based

Framework Advisory Council: Enhancing Patient Care

Through the Comprehensive Integration of

the Pillars of Evidence-based Practice

J Can Chiropr Assoc 2025 (Nov); 69 (3): 224–237 ~ FULL TEXT

Supporting chiropractors to deliver Evidence Based Care (EBC) is an important role that professional organizations fulfill in the practice ecosystem. This is a journey that can be accelerated when there is a shared understanding of the elements of Evidence Based Practice (EBP) and the benefits that accrue when applied comprehensively to patient care. The Ontario Chiropractic Association (OCA) undertook a significant project to advance this understanding and enhance these benefits. This paper describes the principles, processes and outputs of our work, which is a series of papers examining the EBP framework in detail. It details why this work is necessary for the chiropractic profession, how it was accomplished, and introduces the themes of each of the six other papers in the series. We aim to support chiropractors in delivering comprehensive care through the application of the evidence-based framework enabling them to practice within the full chiropractic scope of practice in compliance with applicable regulations and legislations.

Author’s note: This paper is one of seven in a series exploring contemporary perspectives on the application of the evidence-based framework in chiropractic care. The Evidence Based Chiropractic Care (EBCC) initiative aims to support chiropractors in their delivery of optimal patient-centred care. We encourage readers to review all papers in the series.

|

|

Conceptualizing the Evidence Pyramid For Use in

Clinical Practice: A Narrative Literature Review

J Can Chiropr Assoc 2025 (Nov); 69 (3): 238–254 ~ FULL TEXT

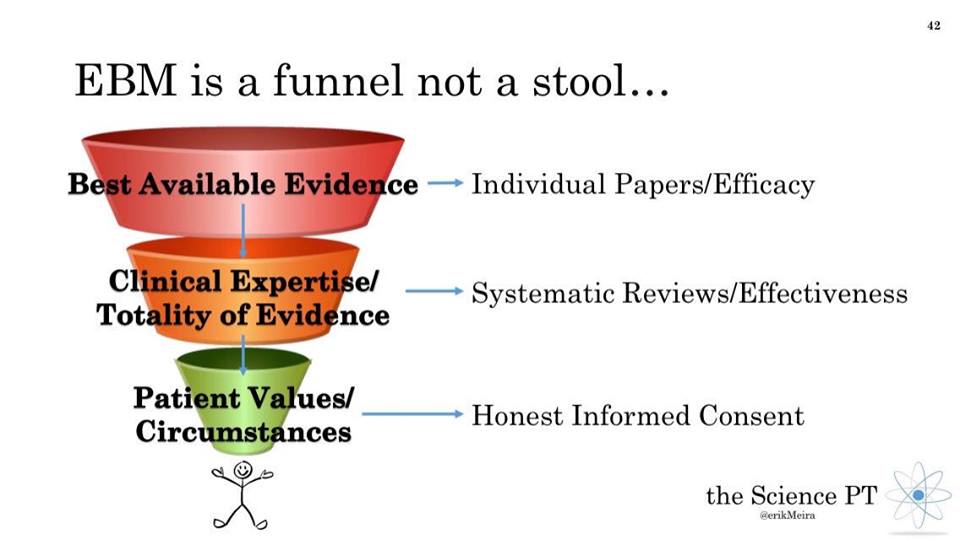

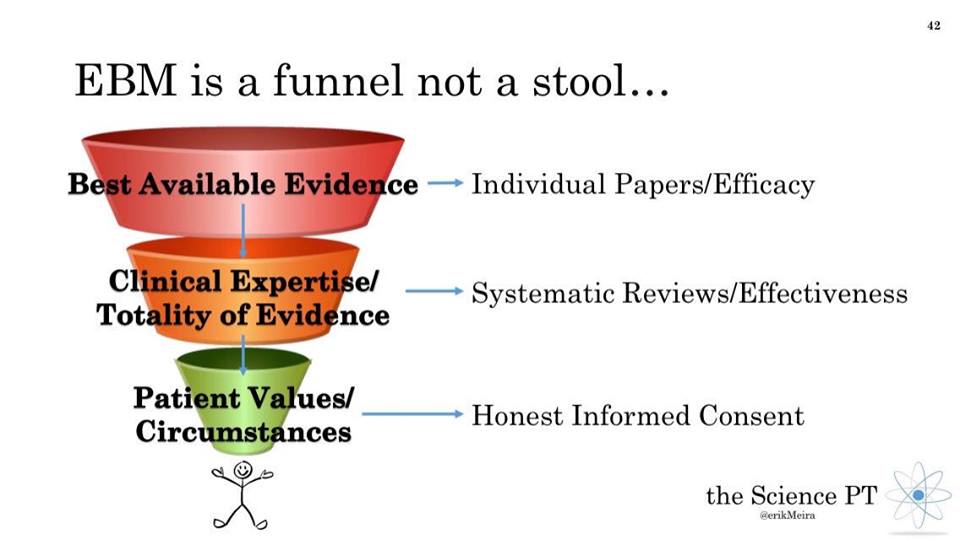

In line with the model by Haynes et al. [8], preliminary findings of our review suggest that the value placed on clinical expertise, as the central pillar of EBP, reinforces that care is delivered in collaboration with patients and their unique values and clinical circumstances, supported by the best available research evidence.

Clinical questions, including those that are qualitative in nature, must be answered using the most appropriate research methodologies (i.e., quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods). As clinicians and researchers, the manner in which questions are framed along with the language that is used, are essential for structuring and seeking research that helps to inform clinical practice. The principles and goals that were initially developed in EBP continue to be informative and ought to be applied in a dynamic and contextualized manner as intended. [2]

|

|

Conceptualizing Clinical Expertise in Evidence-based

Practice: A Narrative Literature Review With

Implications for Clinical Decision-making

J Can Chiropr Assoc 2025 (Nov); 69 (3): 255-272 ~ FULL TEXT

This review provides examples of how clinical expertise can be developed and maintained over time and the importance of ongoing participation in a clinician’s profession to realize the status of possessing and continually advancing clinical expertise. It highlights that clinical expertise is a lifelong, dynamic, evolutionary process in which clinicians should engage throughout their professional careers. Newer approaches to EBP such as the Hayne’s model recognize that clinical expertise (developed through personal experience, keeping current with research and lifelong learning) is an important element in ensuring the delivery of quality care to patients.

|

|

Person-centred Care in Chiropractic: A Foundational But

Evolving Commitment in Contemporary Practice

J Can Chiropr Assoc 2025 (Nov); 69 (3): 273–280 ~ FULL TEXT

Person-centred care (PCC) is a defining feature of evidence-based chiropractic care. It enhances patient and clinician outcomes, while reflecting the profession’s foundational values. PCC is not simply an interpersonal dynamic. It is a justice-oriented, evidence-informed and relational process. Practicing PCC consistently requires more than intent, it demands action. Chiropractors must engage patients as partners, organizations must invest in supportive systems, and patients must be empowered to participate fully in care. Barriers like time, training, and infrastructure are real, but solutions exist in leadership, education, practical tools, and reflective practice.

|

|

Enhancing Evidence-based Chiropractic Practice:

Bridging the Knowledge-to-Action Gap for the

Needs of Community-based Chiropractors

J Can Chiropr Assoc 2025 (Nov); 69 (3): 281–308 ~ FULL TEXT

To bridge the knowledge-to-action (KTA) gap in the chiropractic profession, chiropractors should engage in learning environments to develop necessary Evidence Based Practice (EBP) skills, while associations should focus on supporting and incentivizing chiropractors to enhance their knowledge translation (KT) abilities.

|

|

When There is Little or No Research Evidence:

A Clinical Decision Tool

J Can Chiropr Assoc 2025 (Nov); 69 (3): 309–329 ~ FULL TEXT

Despite advancements in research and guidelines of healthcare, there are still situations where clinicians may lack experience or face limited evidence to inform decision-making. In these situations, healthcare providers should provide care within their scope of practice considering all available evidence-based options, the patient's preferences, and the clinical context through a clinical expertise lens. This decision-making tool serves as a guide for patient-centred clinical decision-making in chiropractic care. It integrates clinical expertise with the pillars of evidence-based practice, taking into account the best available research evidence, patient preferences, and the clinical context. Examples are provided on using the tool within chiropractic care for conditions with large bodies of supporting evidence (e.g., low back pain), and conditions with little to no evidence (e.g., Parkinson's disease), to illustrate the broad applicability of how to use (and how not to use) this tool in the field of chiropractic care.

|

|

|

A Cross-sectional Study of Chiropractic Students' Research

Readiness Using the Academic Self-Concept Analysis Scale

Journal of Chiropractic Education 2017 (Aug 2) [Epub] ~ FULL TEXT

This study found that the majority of chiropractic students display the attributes of self-regulation, general intellectual abilities, motivation, and creativity that would be well suited and oriented to a research and evidence–based chiropractic curriculum. For reasons that require further elucidation through research, the final-year students’ self-perception indicated a less oriented attitude toward these domains compared to the entry-level students

|

|

Evidence-Based Practice and Chiropractic

Chiropractic Journal of Australia 2016 (Dec); 44 (4): 308–319 ~ FULL TEXT

It is one thing to argue a point of view. It is another thing entirely to understand both sides of the argument and to demonstrate a knowledge, dare one say an evidence-based knowledge, of one’s viewpoint. It is hoped that the points raised in this discussion paper will be addressed, either in writing and publication, or by symposia, and the chiropractic profession can continue to grow its areas of best practice, both clinical and academic.

|

|

Commentary: Is EBM Damaging the Social Conscience of Chiropractic?

Chiropractic Journal of Australia 2016 (Dec); 44 (3): 203–213 ~ FULL TEXT

Some European chiropractic institutions issued a communiqué [3] at the 2015 scientific meeting conducted by the World Federation of Chiropractic in Athens. [4] The communiqué includes the statement:

The teaching of vertebral subluxation complex as a vitalistic construct that claims that it is the cause of disease is unsupported by evidence. Its inclusion in a modern chiropractic

curriculum in anything other than an historical context is therefore inappropriate and unnecessary. [3]

The implications of the position promulgated in their document deserve close scrutiny.

|

|

Evidence-based Practice, Research Utilization, and

Knowledge Translation in Chiropractic:

A Scoping Review

BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016 (Jul 13); 16 (1): 216 ~ FULL TEXT

Evidence-based practice (EBP), research utilization (RU), and knowledge translation (KT) are interrelated concepts that pertain to the identification, utilization and application of knowledge from research sources to clinical practice. EBP has been defined as “the integration of clinical expertise, patient values, and the best research evidence into the decision making process for patient care”. [1]

RU is a sub-set of EBP, which refers to “that process by which specific research-based knowledge is implemented in practice”. [2]

KT, on the other hand, emphasizes the synthesis, dissemination, exchange and application of knowledge from research findings, and from other sources, to influence changes in practice and improve health outcomes. [3] Thus, KT aims to help bridge the gap between research findings and what is routinely done in practice.

|

|

Clinical Practice Guideline:

Chiropractic Care for Low Back Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016 (Jan); 39 (1): 1–22 ~ FULL TEXT

To facilitate best practices specific to the chiropractic management of patients with common, primarily musculoskeletal disorders, the profession established the Council on Chiropractic Guidelines and Practice Parameters (CCGPP) in 1995. [6] The organization sponsored and/or participated in the development of a number of “best practices” recommendations on various conditions. [21–32] With respect to chiropractic management of LBP, a CCGPP team produced a literature synthesis [8] which formed the basis of the first iteration of this guideline in 2008. [9] In 2010, a new guideline focused on chronic spine-related pain was published, [12] with a companion publication to both the 2008 and 2010 guidelines published in 2012, providing algorithms for chiropractic management of both acute and chronic pain. [10] Guidelines should be updated regularly. [33, 34] Therefore, this article provides the clinical practice guideline (CPG) based on an updated systematic literature review and extensive and robust consensus process. [9–12]

|

|

Self-reported Attitudes, Skills and Use of Evidence-based Practice

Among Canadian Doctors of Chiropractic: A National Survey

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2015 (Dec); 59 (4): 332–348 ~ FULL TEXT

While most Canadian chiropractors held positive attitudes towards EBP, believed EBP was useful, and were interested in improving their skills in EBP, many did not use research evidence or CPGs to guide clinical decision making. Our findings should be interpreted cautiously due to the low response rate.

|

|

US Chiropractors' Attitudes, Skills and Use of Evidence-

based Practice: A Cross-sectional National Survey

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2015 (May 4); 23: 16 ~ FULL TEXT

American chiropractors appear similar to chiropractors in other countries, and other health professionals regarding their favorable attitudes towards EBP, while expressing barriers related to EBP skills such as research relevance and lack of time. This suggests that the design of future EBP educational interventions should capitalize on the growing body of EBP implementation research developing in other health disciplines. This will likely include broadening the approach beyond a sole focus on EBP education, and taking a multilevel approach that also targets professional, organizational and health policy domains.

|

|

Adherence to Clinical Practice Guidelines Among Three

Primary Contact Professions: A Best Evidence Synthesis

of the Literature for the Management of Acute

and Subacute Low Back Pain

J Can Chiropr Assoc 2014 (Sept); 58(3): 220–237 ~ FULL TEXT

To determine adherence to clinical practice guidelines in the medical, physiotherapy and chiropractic professions for acute and subacute mechanical low back pain through best-evidence synthesis of the healthcare literature. Of the three professions examined, 73% of chiropractors adhered to current clinical practice guidelines, followed by physiotherapists (62%) and then medical practitioners (52%).

|

|

How to Proceed When Evidence-based Practice Is Required

But Very Little Evidence Available?

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2013 (Jul 10); 21 (1): 24 ~ FULL TEXT

All clinicians of today know that scientific evidence is the base on which clinical practice should rest. However, this is not always easy, in particular in those disciplines, where the evidence is scarce. There is also the issue of the definition of “evidence”. Textbooks have been devoted to this. Throughout this text we shall assume that “evidence” equals the “best evidence” available at the time, when evaluating the value of a clinical procedure.

|

Knowledge Transfer Within the Canadian Chiropractic Community

|

Part 1: Understanding Evidence-Practice Gaps

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2013 (Jun); 57 (2): 111–115 ~ FULL TEXT

This two-part commentary aims to provide a basic understanding of knowledge translation (KT), how KT is currently integrated in the chiropractic community and our view of how to improve KT in our profession. Part 1 presents an overview of KT and discusses some of the common barriers to successful KT within the chiropractic profession. Part 2 will suggest strategies to mitigate these barriers and reduce the evidence-practice gap for both the profession at large and for practicing clinicians.

|

|

Part 2: Narrowing the Evidence-Practice Gap

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2014 (Sep); 58 (3): 206–214 ~ FULL TEXT

This two-part commentary aims to provide clinicians with a basic understanding of knowledge translation (KT), a term that is often used interchangeably with phrases such as knowledge transfer, translational research, knowledge mobilization, and knowledge exchange. [1] Knowledge translation, also known as the science of implementation, is increasingly recognized as a critical element in improving healthcare delivery and aligning the use of research knowledge with clinical practice. [2] The focus of our commentary relates to how these KT processes link with evidence-based chiropractic care.

|

|

|

Evidence-Based Practice and Chiropractic Care

J Evid Based Comp Altern Med. 2012 (Dec 28); 18 (1): 75–79 ~ FULL TEXT

Evidence-based practice has had a growing impact on chiropractic education and the delivery of chiropractic care. For evidence-based practice to penetrate and transform a profession, the penetration must occur at 2 levels. One level is the degree to which individual practitioners possess the willingness and basic skills to search and assess the literature. Chiropractic education received a significant boost in this realm in 2005 when the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine awarded 4 chiropractic institutions R25 education grants to strengthen their research/evidence-based practice curricula. The second level relates to whether the therapeutic interventions commonly employed by a particular health care discipline are supported by clinical research. A growing body of randomized controlled trials provides evidence of the effectiveness and safety of manual therapies.

|

|

Evaluation of the Effects of an Evidence-Based Practice Curriculum

on Knowledge, Attitudes, and Self-Assessed Skills and Behaviors

in Chiropractic Students

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012 (Nov); 35 (9): 701–709 ~ FULL TEXT

The implementation of a broad-based EBP curriculum in a chiropractic training program is feasible and can result in 1) the acquisition of knowledge necessary to access and interpret scientific literature, 2) the retention and improvement of these skills over time, and 3) the enhancement of self-reported behaviors favoring utilization of quality online resources. It remains to be seen whether EBP skills and behaviors can be translated into private practice.

|

|

Developing Clinical Practice Guidelines: Reviewing, Reporting,

and Publishing Guidelines; Updating Guidelines; and the

Emerging Issues of Enhancing Guideline Implementability

and Accounting for Comorbid Conditions

in Guideline Development

Implementation Science 2012 (Jul 4); 7: 62 ~ FULL TEXT

Clinical practice guidelines are one of the foundations of efforts to improve health care. In 1999, we authored a paper about methods to develop guidelines. Since it was published, the methods of guideline development have progressed both in terms of methods and necessary procedures and the context for guideline development has changed with the emergence of guideline clearing houses and large scale guideline production organisations (such as the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence). It therefore seems timely to, in a series of three articles, update and extend our earlier paper. In this third paper we discuss the issues of: reviewing, reporting, and publishing guidelines; updating guidelines; and the two emerging issues of enhancing guideline implementability and how guideline developers should approach dealing with the issue of patients who will be the subject of guidelines having co-morbid conditions.

|

|

Evidence-based Medicine:

Revisiting the Pyramid of Priorities

J Bodywork & Movement Therapies 2012 (Jan); 16 (1): 42–49 ~ FULL TEXT

In summary, concepts of EBM have been undergoing continuous revisions and need to remain flexible in order for the most effective healthcare decisions to be made. It is the successful fusion of evidence from the literature, clinical judgment from the physician, and expectations and values of the patient which ultimately will determine the best course of therapy and which is currently being rediscovered and readmitted into the pantheon of EBM. Because all forms of quantitative experimentation can never be construed as absolute means of knowing by their reliance upon statistical probabilities which are culminated in

meta-analyses done must keep in mind the importance of allowing multiple forms of inquiry and experimental design to effectively answer a research question. This ecumenical approach to EBM should, in the final analysis, yield the most successful outcomes in healthcare.

|

|

The Obstacles and Barriers to CAM Research

Anthony Rosner, PhD, Research Director of FCER

Anthony Rosner, PhD, Research Director of FCER ~ FULL TEXT

The efforts to launch and develop a National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine within the framework of the NIH are indeed admirable, taking the Center from a humble $2M annual budget in 1991 to one that approaches $70M today. This has taken place despite the comments of highly visible and influential individuals within the medical community to discredit alternative medicine in virtually any shape or form. Following are what I believe to be the most significant barriers to research efforts in alternative medicine, the barriers having either remained in place or only recently having been removed.

|

|

The Trials of Evidence:

Interpreting Research and the Case for Chiropractic

The Chiropractic Report (July 2011) ~ FULL TEXT

For the great majority of patients with both acute and chronic low-back pain, namely those without diagnostic red flags, spinal manipulation is recommended by evidence-informed guidelines from many authoritative sources – whether chiropractic (the UK Evidence Report from Bronfort, Haas et al. [1]), medical (the 2007 Joint Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society [2]) or interdisciplinary (the European Back Pain Guidelines [3]).

|

|

International Web Survey of Chiropractic Students

About Evidence-based Practice: A Pilot Study

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2011 (Mar 3); 19 (1): 6 ~ FULL TEXT

The results of this survey indicate that although it appears feasible to conduct a web-based survey with chiropractic students, significant stakeholder participation is crucial to improve response rates. Students had relatively positive attitudes toward EBP. However, they felt they needed more training in EBP and based on the knowledge questions they may need further training about basic research concepts.

|

|

The Mythology Of Science-Based Medicine

The Huffington Post (2–25–2011) ~ FULL TEXT

One side, mainstream medicine, promotes the notion that it alone should be considered "real" medicine, but more and more this claim is being exposed as an officially sanctioned myth. When scientific minds turn to tackling the complex business of healing the sick, they simultaneously warn us that it's dangerous and foolish to look at integrative medicine, complementary and alternative medicine, or God forbid, indigenous medicine for answers. Because these other modalities are enormously popular, mainstream medicine has made a few grudging concessions to the placebo effect, natural herbal remedies, and acupuncture over the years. But M.D.s are still taught that other approaches are risky and inferior to their own training; they insist, year after year, that all we need are science-based procedures and the huge spectrum of drugs upon which modern medicine depends.

|

|

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and

Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement

Int J Surg. 2010 (May 26); 8 (5): 336–341 ~ FULL TEXT

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have become increasingly important in health care. Clinicians read them to keep up to date with their field, [1, 2] and they are often used as a starting point for developing clinical practice guidelines. Granting agencies may require a systematic review to ensure there is justification for further research, [3] and some health care journals are moving in this direction. [4] As with all research, the value of a systematic review depends on what was done, what was found, and the clarity of reporting. As with other publications, the reporting quality of systematic reviews varies, limiting readers’ ability to assess the strengths and weaknesses of those reviews.

|

|

The Shifting Sands of EBM (Evidence-Based Medicine)

Anthony L. Rosner, PhD, Research Director at Parker College of Chiropractic ~ FULL TEXT

Cracks in the foundation of the conventional wisdom of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) began to appear in the 1980s when the quality of observational (cohort, case series) studies was found to improve such that their predictive value in clinical situations could now be compared to that seen in the more rigorous RCTs. [1, 2] At the same time, RCTs began to be seriously challenged due to their limited applicability in clinical situations. [3, 4] Among other problems, RCTs were found to lack insight into lifestyles, nutritional interventions and long-latency deficiency diseases. [5] Quirks have even surfaced which demonstrate how the exalted meta-analysis is subject to human error and bias. [6]

|

|

What Constitutes Evidence For Best Practice?

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008 (Nov); 31 (9): 637–643 ~ FULL TEXT

The Council on Chiropractic Guidelines and Practice Parameters (CCGPP) has been charged with the task of developing a catalogue and summarizing the evidence as it relates to chiropractic practice. The goal is to establish a more equitable and fairer basis for judgments of health care delivery specifically as it applies to the profession. After years of discussion and debate, the Commission of the CCGPP recommended in 2001 the establishment of a new approach – the development of an evidence database – available to all stakeholders.

|

|

GRADE: An Emerging Consensus on Rating Quality

of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations

British Medical Journal 2008 (Apr 26); 336 (7650): 924–926 ~ FULL TEXT

Guidelines are inconsistent in how they rate the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations. This article explores the advantages of the GRADE system, which is increasingly being adopted by organisations worldwide.

|

|

What Have We Learned About the Evidence-informed

Management of Chronic Low Back Pain?

Spine J 2008 (Jan); 8 (1): 266-277 ~ FULL TEXT

As noted in the review of the economic burden of LBP in this special focus issue, the magnitude of this problem is likely increasing in the United States and the question that needs to be answered is whether any treatment should be offered and widely used before there being sufficient research evidence to establish its efficacy, safety, and cost effectiveness. It is a generally accepted principle in most fields of health care that a treatment should not be offered to the public until there is sufficient evidence supporting its safety and effectiveness and a consensus by clinicians of different backgrounds as to its most appropriate indications and contraindications. It should be evident to most readers that this is not the norm when dealing with CLBP and additional research is required to achieve this long-term goal. In the interim, patients, clinicians, third-party payers, and policy makers have a responsibility to become thoroughly familiar with, critically appraise, compare, and openly discuss the best available evidence presented in this special focus issue. In this supermarket of over 200 available treatment options for CLBP, we are still in the era of caveat emptor (buyer beware). The enthusiastic support by providers of any treatment should be considered when reviewing available research evidence that supports its use. It is hoped that this special focus issue will provide a starting point for stakeholders desiring quality information to make decisions about the evidenceinformed management of CLBP.

|

|

Evidence-informed Management of Chronic Low Back Pain

with Spinal Manipulation and Mobilization

Spine J. 2008 (Jan); 8 (1): 213–225 ~ FULL TEXT

For CLBP, there is moderate evidence that SMT with strengthening exercise is similar in effect to prescription nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with exercise in both the short term and long term. There is also moderate evidence that flexion-distraction MOB is superior to exercise in the short term and superior/similar in the long term. There is moderate evidence that a regimen of high-dose SMT is superior to low-dose SMT in the very short term. There is limited to moderate evidence that SMT is better than physical therapy and home exercise in both the short and long term. There is also limited evidence that SMT is as good or better than chemonucleolysis for disc herniation in the short and long term. There is limited evidence that MOB is inferior to back exercise after disc herniation surgery.

|

|

Evidence-Based Medicine:

Best Practices and Practice Guidelines

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2007 (Nov); 30 (9): 615–616 ~ FULL TEXT

Any thoughtful physician would want to provide the best services for his or her patients, and as far as we know, this has been a precept that has been accepted since the beginning of recorded history as it relates to the practice of healing. This position is one of simple ethical behavior and is part of any vow taken by doctors who practice in one of the branches of medicine. This ethic is characterized by the old and often repeated principle “primum non nocere,” which, interpreted means “first do no harm.”

|

|

Introduction to and Techniques of Evidence-based Medicine

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007 (Sep 1); 32 (19 Suppl): S66–72 ~ FULL TEXT

Capable clinicians must understand the importance of the research question, study design, and outcomes to apply the best available evidence to patient care. Treatment recommendations evolving from critical appraisal, however, are no longer just based on levels of evidence, but also the risk benefit ratio and cost. The true philosophy of EBM, however, is not for research to supplant individual clinical experience and the patients’ informed preference, but to integrate them with the best available research. Health policy makers, editorial boards, granting agencies, and payers must learn that EBM is not always a RCT. They must realize that the question being asked and the research circumstances dictate the study design. Finally, they must not diminish the role of clinical expertise and informed patient preference in EBM as it provides the generalizability so often lacking in controlled experimental research.

|

|

When Evidence and Practice Collide

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2005 (Oct); 28 (8): 551–553 ~ FULL TEXT

“Until now, we believed that the best way to transmit knowledge from its source to its use in patient care was to first load the knowledge into human minds… and then expect those minds, at great expense, to apply the knowledge to those who need it. However, there are enormous ‘voltage drops’ along this transmission line for medical knowledge.”

|

|

Fostering Critical Thinking Skills:

A Strategy for Enhancing Evidence Based Wellness Care

Chiropractic & Osteopathy 2005 (Sep 8); 13 (1): 19 ~ FULL TEXT

Chiropractic has traditionally regarded itself a wellness profession. As wellness care is postulated to play a central role in the future growth of chiropractic, the development of a wellness ethos acceptable within conventional health care is desirable. This paper describes a unit which prepares chiropractic students for the role of "wellness coaches". Emphasis is placed on providing students with exercises in critical thinking in an effort to prepare them for the challenge of interfacing with an increasingly evidence based health care system.

|

|

Applying Evidence-Based Health Care to Musculoskeletal

Patients as an Educational Strategy for Chiropractic

Interns (A One-Group Pretest-Posttest Study)

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2004 (May); 27 (4): 253–261 ~ FULL TEXT

The results of this study suggest that having chiropractic interns apply EBHC to actual musculoskeletal patients along with attending EBHC workshops had a positive impact on interns' perceived ability to practice EBHC.

|

|

Fables or Foibles: Inherent Problems with RCTs

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2003 (Sept); 26 (7): 460 ~ FULL TEXT

The 7 case studies reviewed in this report combined with an emerging concept in the medical literature both suggest that reviews of clinical research should accommodate our increased recognition of the values of cohort studies and case series. The alternative would have been to assume categorically that observational studies rather than RCTs (Randomized Controlled Trials) provide inferior guidance to clinical decision-making. From this discussion, it is apparent that a well-crafted cohort study or case series may be of greater informative value than a flawed or corrupted RCT. To assume that the entire range of clinical treatment for any modality has been successfully captured by the precision of analytical methods in the scientific literature, indicates Horwitz, would be tantamount to claiming that a medical librarian who has access to systematic reviews, meta-analyses, Medline, and practice guidelines provides the same quality of health care as an experienced physician.

|

|

Effect of Interpretive Bias on Research Evidence

British Medical Journal 2003 (Jun 28); 326 (7404): 1453–1455 ~ FULL TEXT

Doctors are being encouraged to improve their critical appraisal skills to make better use of medical research. But when using these skills, it is important to remember that interpretation of data is inevitably subjective and can itself result in bias. Facts do not accumulate on the blank slates of researchers' minds and data simply do not speak for themselves. (1) Good science inevitably embodies a tension between the empiricism of concrete data and the rationalism of deeply held convictions. Unbiased interpretation of data is as important as performing rigorous experiments. This evaluative process is never totally objective or completely independent of scientists' convictions or theoretical apparatus. This article elaborates on an insight of Vandenbroucke, who noted that "facts and theories remain inextricably linked... At the cutting edge of scientific progress, where new ideas develop, we will never escape subjectivity." (2) Interpretation can produce sound judgments or systematic error. Only hindsight will enable us to tell which has occurred. Nevertheless, awareness of the systematic errors that can occur in evaluative processes may facilitate the self regulating forces of science and help produce reliable knowledge sooner rather than later.

|

|

Evidence-based Chiropractic Care: Cochrane Systematic

Reviews of Health Care Interventions

J Canadian Chiropractic Assoc 2003 (Mar); 47 (1): 8–16 ~ FULL TEXT

This Adobe Acrobat article (292 KB) states: As a chiropracvtor, you want whats best for your patients. In order to make well-informed clinical decisions, you and your patients require high-quality, up-to-date, trustworthy healthcare information. Such information is available in the Cochrane Library of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions.

|

|

Is Chiropractic Evidence Based? A Pilot Study

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2003 (Jan); 26 (1): 47 ~ FULL TEXT

When patients were used as the denominator, the majority of cases in a chiropractic practice were cared for with interventions based on evidence from good-quality, randomized clinical trials. When compared to the many other studies of similar design that have evaluated the extent to which different medical specialties are evidence based, chiropractic practice was found to have the highest proportion of care (68.3%) supported by good-quality experimental evidence.

|

|

Placebo Surgery

Chiropractic Journal 2002 (Sep) ~ FULL TEXT

Many scientists and clinicians consider the placebo-controlled trial the "gold standard" for evidence-based practice.

Interestingly, surgical procedures are often exempt from such scrutiny. Ethical considerations are considered barriers to the use of placebo-controlled investigations for surgical procedures. [3,4] Interestingly, there have been five studies where placebo surgery was used as a control. The placebo group generally did as well or better than the group receiving the real operation.

Read more about the difficulties of designing a "neutral" sham for a chiropractic (or CAM) trial.

|

|

Evidence-Based Chiropractic Care Part I: Contribution of

Cochrane Collaboration and the Canadian

Cochrane Network and Centre (PDF)

J Canadian Chiropractic Assoc 2002 (Sep); 4 (3): 137–143 ~ FULL TEXT

This Adobe Acrobat article states: Chiropractors are busy health professionals. Like all other health pratitioners today, you do not have the time to read all the literature you ought to review to keep current with new research and the reports of best practices in your profession. Fortunately, there are relaible sources of up-to-date summarized literature available to help you.

|

|

Informatics Skills:

Weakness in the Foundation of Research

Proceedings of the 2002 International Conference on Spinal Manipulation (OCT) ~ FULL TEXT

One of the challenges facing today’s health care professionals is the difficulty in keeping current despite the proliferation of medical literature. This need is compounded with the increasing advocacy for evidence-based medicine. Current estimates suggest that clinicians would need to read 19 articles per day, every day of the year to keep abreast of relevant clinical developments. [1] Other than consulting colleagues in the field or experts, health care professionals can peruse literature reviews for a concise, qualitative or quantitative meta-analysis of pertinent information. However, expert bias and errors in the literature review process has been shown to be a reason for caution. [2] It is often impossible to separate fact from opinion or to decipher the authors’ methods for selecting material. [3]

|

|

Behavioral and Physical Treatments for

Tension-type and Cervicogenic Headache

Duke University Evidence-based Practice Center ~ 2001 ~ FULL TEXT

In 1996, the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) was scheduled to produce a set of clinical practice guidelines on available treatment alternatives for headache. This headache project was based on the systematic evaluation of the literature by a multidisciplinary panel of experts. Due to largely political circumstances, however, their efforts never came to fruition. The work was never released as guidelines, but was instead transformed with modifications and budget cuts into a set of evidence reports on only migraine headache. Thanks to FCER funding, the evidence reports have now been updated on both cervicogenic and tension-type headaches.

You may also download the full 10–page

Duke University Report in Adobe Acrobat format .

You might also enjoy

Dr. Anthony Rosner's recent article on this topic.

|

|

The Evidence House: How to Build an

Inclusive Base for Complementary Medicine

West J Med 2001 (Aug); 175 (2): 79–80 ~ FULL TEXT

We all want good evidence available when making medical decisions. Evidence, however, comes in a variety of forms and purposes, and what may be good for one purpose may not be good for another. The term "evidence-based medicine" (EBM) has become almost a cliché in recent years, being used as a synonym for "good" or "scientific," both to support and refute the value of complementary medicine practices. But EBM takes a narrow view of what constitutes "good" evidence, and it excludes important qualitative and observational information about the use and benefits of complementary medicine.

|

|

The Evidence in Evidence-based Practice:

What Counts and What Doesn't Count?

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2001 (Jun); 24 (5): 362–366 ~ FULL TEXT

For those who are prepared to buy in to EBP, there is a question that is only now being debated in the chiropractic literature. This question, which is being vigorously debated elsewhere in EBP, is one of exactly what does and what does not count as evidence in EBP. In the working definition of EBP, the "evidence" is characterized as being "sound" and generated from "well-conducted research". But what exactly does this mean? For many, the terms sound and well-conducted research are instinctively interpreted as referring to randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The RCT has been designated – in many cases accurately – the gold standard of research designs. Accordingly, the intuitive assumption that only evidence from RCTs counts in EBP is understandable. However, this position is now being challenged, and other designs, such as observational and qualitative research, are being considered legitimate providers of the evidence in EBP. It might be time to look at how these moves will affect chiropractic research in the future.

|

|

Evidence-based Clinical Guidelines for the Management of

Acute Low Back Pain: Response to the Guidelines Prepared for

the Australian Medical Health and Research Council

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2001 (Jun); 24 (3): 214–220 ~ FULL TEXT

In Bogduk's opinion, the major reason for justifying these guidelines in preference to previous multidisciplinary efforts in both the United States1 and the United Kingdom2 is that consensus or expert opinion is no longer to be accepted as a form of evidence. Bogduk claims that all of his conclusions are preferably based on hard evidence from the published clinical trials, yet nowhere in his treatise is there any indication that his own review of the evidence is either systematic or impartial. As I will make clear in what follows, his analysis of the literature pertaining to spinal manipulation in particular is both flawed and incomplete, seriously undermining the credibility of the entire report.

|

|

Evidence-Based Care: From Guidelines to Practice

Dynamic Chiropractic (August 6, 2000)

Specialists of the neuromusculoskeletal (NMS) system have seen tremendous changes in the last decade. "Medicalization" has led to excesses in diagnostic testing and surgery, while chiropractic and psychological approaches have been underutilized. Evidence pointing out that ineffective approaches were overutilized and effective approaches underutilized has been summarized and published in guidelines throughout the world.

|

|

Interpreting The Evidence: Choosing Between

Randomised And Non-randomised Studies

British Medical Journal 1999 (Jul 31); 319: 312–315 ~ FULL TEXT

Evaluations of healthcare interventions can either randomise subjects to comparison groups, or not. In both designs there are potential threats to validity, which can be external (the extent to which they are generalisable to all potential recipients) or internal (whether differences in observed effects can be attributed to differences in the intervention). Randomisation should ensure that comparison groups of sufficient size differ only in their exposure to the intervention concerned. However, some investigators have argued that randomised controlled trials (RCTs) tend to exclude, consciously or otherwise, some types of patient to whom results will subsequently be applied.

|

|

Applying Research Evidence to Individual Patients

British Medical Journal 1998 (May 30); 316 (7139): 1621–1622 ~ FULL TEXT

At the heart of clinical medicine is an unresolved conflict between the essentially case based nature of clinical practice and the mainly population based nature of the research evidence. While clinicians are exhorted to use up to date research evidence to give patients the best possible care, actually doing so in individual patients is difficult.

|

|

Qualitative Research and Evidence Based Medicine

British Medical Journal 1998 (Apr 18); 316 (7139): 1230–1232 ~ FULL TEXT

Qualitative research may seem unscientific and anecdotal to many medical scientists. However, as the critics of evidence based medicine are quick to point out, medicine itself is more than the application of scientific rules. Clinical experience, based on personal observation, reflection, and judgment, is also needed to translate scientific results into treatment of individual patients.

|

|

Evidence-Based Medicine:

What It Is and What It Isn't

British Medical Journal 1996 (Jan 13); 312: 71–72 ~ FULL TEXT

Evidence-based medicine is the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The practice of evidence-based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research. By individual clinical expertise we mean the proficiency and judgement that individual clinicians acquire through clinical experience and clinical practice.

|

|

The Need for Evidence-based Medicine

J Royal Society of Medicine 1995 (Nov); 88: 620–624 ~ FULL TEXT

As physicians, whether serving individual patients or populations, we always have sought to base our decisions and actions on the best possible evidence. The ascendancy of the randomized trial heralded a fundamental shift in the way that we establish the clinical bases for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutics. The ability to track down, critically appraise (for its validity and usefulness), and incorporate this rapidly growing body of evidence into one's clinical practice has been named 'evidence-based medicine [5, 6] (EBM).

|

|

Proposal for Establishing Structure and Process in the

Development of Implicit Chiropractic Standards of Care

and Practice Guidelines

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1992 (Sep); 15 (7): 430–438

This proposal offers a preliminary definition of the structure and process, including a "seed" policy statement and decision flow chart, specific to guideline development. Once the structure and process of guideline development for chiropractic are defined, the profession can then present this product to federal and state agencies, private sector health care purchasers, patient advocacy groups and other stakeholders of chiropractic care.

|

|

Evidence-based Introduction

|

|

Thanks to Michael T. Haneline, DC, MPH for providing the following materials, to help our profession utilize evidence-based articles!

He (previously) taught classes on Evidence-based chiropractic at Palmer West.

“Don't have a clue how to interpret the various statistical tests utilized in many of the journal articles in order to practice evidence-based chiropractic?

Then read these two brief articles that provide an overview of some important statistical concepts, required to understand the methods involved in research.

You may want to read the “Descriptive Statistics” article first.”

|

|

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics (DS) characterize the shape, central tendency, and variability of a set of data.

When referring to a population, these characteristics are known as parameters; with sample data, they are referred to as statistics.

Word document (285 KB)

OR

Acrobat file (80 KB)

|

|

Common Statistical Tests

The purpose of this brief discourse on statistical tests is to enable chiropractors to better understand the mechanisms used by researchers as they evaluate and then draw conclusions from data in scientific articles. The emphasis is on understanding the concepts, so mathematics is purposefully deemphasized.

Word document (275 KB)

OR

Acrobat file (164 KB)

|

The Evidence-based Chiropractic (EBC) Class Notes

The Evidence-based Chiropractic (EBC) Class Notes

These are the Powerpoint class notes for the Evidence-based class that

Michael T. Haneline, DC, MPH, FICR taught at Palmer College of Chiropractic West.

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: Literature Searching

Chapter 2: Literature Searching

Chapter 3: Biostatistics Basics

Chapter 3: Biostatistics Basics

Chapter 4: Inferential Statistics

Chapter 4: Inferential Statistics

Chapter 5: Experimental Designs

Chapter 5: Experimental Designs

Chapter 6: Literature Review Designs

Chapter 6: Literature Review Designs

Chapter 7: Case Designs

Chapter 7: Case Designs

Chapter 8: Epidemiology

Chapter 8: Epidemiology

Chapter 9: Reliability and Validity Designs

Chapter 9: Reliability and Validity Designs

Chapter 10: Evidence-based Chiropractic and Documentation

Chapter 10: Evidence-based Chiropractic and Documentation

Chapter 11: Evidence-based Chiropractic (EBC) in Everyday Practice

Chapter 11: Evidence-based Chiropractic (EBC) in Everyday Practice

Chapter 12: Appraisal of Two Randomized Clinical Trials

Chapter 12: Appraisal of Two Randomized Clinical Trials

Chapter 13: Clinical Problem Solving Strategies

Chapter 13: Clinical Problem Solving Strategies

|

Evidence-Based Toolkit for Clinicians

Palmer College of Chiropractic

The Evidence-Based Toolkit for Clinicians is a collection of resources, tools, and services to help you provide evidence-based care to your patients.

|

|

Clinical Standards, Protocols and Education

(CSPE) Protocols and Care Pathways

University of Western States

UWS care pathways and protocols provide evidence-informed, consensus-based guidelines to support clinical decision making. To best meet a patient’s healthcare needs, variation from these guidelines may be appropriate based on more current information, clinical judgment of the practitioner, and/or patient preferences.

|

|

The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM)

University of Oxford

The CEBM aims to develop, teach and promote evidence-based health care through a variety of methods so that all healthcare professionals can maintain the highest standards of medicine.

|

|

National Guideline Clearinghouse

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)

AHRQ's National Guideline Clearinghouse is an an Internet repository of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines launched in 1998.

|

|

Patient Safety Network

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)

This site is a valuable gateway to resources for improving patient safety and preventing medical errors and is the first comprehensive effort to help healthcare providers, administrators, and consumers learn about all aspects of patient safety.

|

Return to ChiroZine

Return to the LINKS

Return to GUIDELINES

Return to the DOCUMENTATION

Since 7–29–2001

Updated 1–30–2026

|

Anthony Rosner, PhD, Research Director of FCER

The Evidence-based Chiropractic (EBC) Class Notes

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: Literature Searching

Chapter 3: Biostatistics Basics

Chapter 4: Inferential Statistics

Chapter 5: Experimental Designs

Chapter 6: Literature Review Designs

Chapter 7: Case Designs

Chapter 8: Epidemiology

Chapter 9: Reliability and Validity Designs

Chapter 10: Evidence-based Chiropractic and Documentation

Chapter 11: Evidence-based Chiropractic (EBC) in Everyday Practice

Chapter 12: Appraisal of Two Randomized Clinical Trials

Chapter 13: Clinical Problem Solving Strategies