Enhancing Evidence-based Chiropractic Practice:

Bridging the Knowledge-to-Action Gap for the

Needs of Community-based ChiropractorsThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Can Chiropr Assoc 2025 (Nov); 69 (3): 281–308 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Caroline Brereton, MBA • Peter C. Emary, DC, PhD • Carol Cancelliere, DC, MPH, MBA, PhD • Jonathan Murray, BSc, MSc • Jessica M. Parish, BA (Hons), MA, PhD • Adrienne Shnier, MA, PhD, JD • Ontario Chiropractic Association • Brian Gleberzon, BA, DC, MHSc, PhD

Ontario Chiropractic Association,

Toronto, ON.

Objective: To summarize key factors of knowledge translation (KT) and offer actionable recommendations to improve uptake and application of evidence-based practice (EBP) in chiropractic care.

Methods: We conducted a narrative review searching for KT literature in PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus from January 2016 to August 2024. Titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility and relevant articles underwent full-text review. We used an expert consensus approach to form our recommendations.

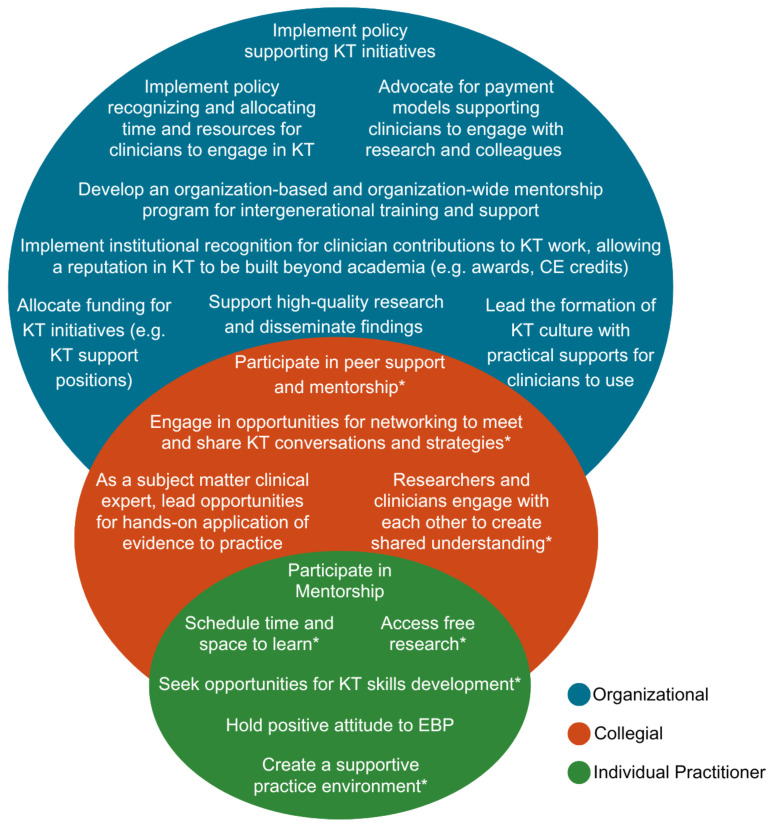

Results: We identified KT barriers and facilitators at individual, collegial, and organizational levels. Recommendations include advocating for individual clinicians to pursue continuous education and mentorship, and for professional organizations to support KT funding and foster supportive and collaborative environments for individual clinicians to engage in KT.

Conclusions: To bridge the knowledge-to-action (KTA) gap in the chiropractic profession, chiropractors should engage in learning environments to develop necessary EBP skills, while associations should focus on supporting and incentivizing chiropractors to enhance their KT abilities.

Author’s note: This paper is one of seven in a series exploring contemporary perspectives on the application of the evidence-based framework in chiropractic care. The Evidence Based Chiropractic Care (EBCC) initiative aims to support chiropractors in their delivery of optimal patient-centred care. We encourage readers to review all papers in the series.

Keywords: chiropractic; clinical skills; evidence-based practice; institutional practice; interdisciplinary research; knowledge translation; organizational policy.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is essential to enabling the highest standard of clinical care. Central to EBP is the incorporation of the best available research evidence with clinical expertise, clinical circumstances, and patient preferences, as we discuss in companion articles throughout this JCCA special edition. [1, 2] Integrating research evidence into each of these factors of EBP facilitates optimal clinical decision-making, contributing to enhanced patient outcomes. [1]

Effectively applying the best evidence into practice is dependent on the resources available to a clinician, as well as on a clinician’s ability to translate new knowledge into improved practice. [3] This process, however, is often ‘slow and haphazard’, thereby delaying the benefits of new research and subsequently, improved outcomes for patients. [4, 5] There are also inconsistencies across disciplines in the application of high-quality research in practice, posing risk of providing potentially ineffective or even harmful treatments through either outdated or prematurely adopted research. [4] Clinicians also face ever-expanding bodies of literature, making it challenging to keep up-to-date with the latest evidence. [4] Additionally, the support available to clinicians is context-dependent, making it harder for clinicians in private practice settings to efficiently translate new evidence into practice. In Ontario, for example, the majority of chiropractic practitioners are in small, community-based private practice settings, and do not have access to the same institutional supports as other healthcare professions, such as medicine or nursing, practising in the publicly-funded system.

The increasing availability of high-quality research, corresponding with a lack of uptake and utilization of such research has been described as the “knowledge-to-action (KTA) gap”. [4] This gap between what clinicians know as opposed to what clinicians actually do has been identified to be an important determinant of overuse, misuse, and underuse of healthcare services, caused by the limited ability of healthcare providers to translate research, policy, and new technology into practice safely and appropriately. [6] As a consequence, patients may not always receive safe and effective healthcare, and even if they do it may not be in a timely manner. [6]

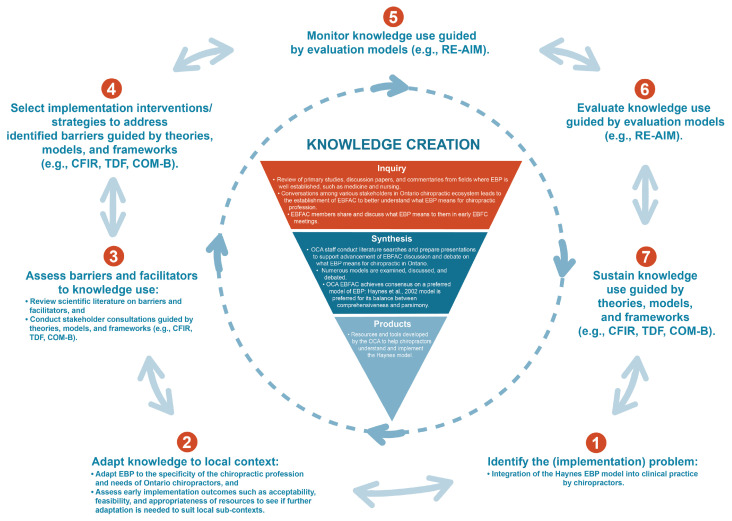

Figure 1 The term “knowledge translation (KT)” has gained prominence in Canada, where KT refers to addressing this gap between knowledge gained from research and knowledge implementation by key stakeholders, including patients, policy-makers, healthcare professionals and others, to improve health outcomes and healthcare efficiency. [4] Bridging the KTA gap therefore requires identifying and overcoming barriers to KT at each of these levels (Figure 1).

One significant, looming KTA barrier is the lack of conceptual clarity regarding the meaning of “knowledge translation”, creating a source of confusion for researchers and clinicians alike. [4, 5] With many existing definitions of KT, one that has been largely adopted comes from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) in 2007, [5] which was subsequently updated in 2016 to describe KT as a:“…dynamic and iterative process that includes synthesis, dissemination, exchange and ethically-sound application of knowledge to improve the health of Canadians, provide more effective health services and products and strengthen the healthcare system”. [3]

Nonetheless, ambiguity surrounding a universal understanding of KT remains. Potentially explaining, in part, findings from a recent scoping review analyzing KT, evidence implementation, and research utilization in chiropractic that found there is still a KTA gap between research and practice despite favourable attitudes toward EBP among clinicians. [7] Collectively, this calls for more robust dissemination and implementation of research to improve the application of research into practice. [4, 7] Accordingly, the objectives of our paper were to:

(1) Summarize key facilitators and barriers to KT of EBP from the published literature; and

(2) offer actionable recommendations to improve the uptake and application of EBP in routine chiropractic care.

Methods

Working group

The working group included researchers (n=4), clinicians (n=4), educators (n=3), and Ontario Chiropractic Association staff members (n=2). The group’s content expertise and experiential knowledge of the unique challenges faced by healthcare professionals working in private community-based practice settings were incorporated with the literature review findings to guide recommendations.

Study design

We conducted a narrative review of the literature to summarize barriers and facilitators to KT of care providers across all healthcare relevant disciplines, at the individual, collegial/peer, and organizational level. The working group then reviewed the findings and developed actionable recommendations to improve the uptake and application of EBP into chiropractic care.

Data sources and searches

We searched PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus databases to identify KT articles published between January 1, 2016, and August 1, 2024. This date range was imposed to extend the findings of the 2016 scoping review by Bussières et al. [7] and provide a contemporary summary of barriers and facilitators to KT that are applicable to today’s clinical chiropractic environment. We employed a range of search terms to capture pertinent literature on barriers and facilitators to knowledge translation (KT), evidence integration (EI), or research utilization (RU), in line with our objectives (Appendix 1).

Selection criteria

We included empirical research articles as well as secondary sources of evidence (e.g., systematic, scoping, or narrative reviews, and commentaries) that explored the barriers, facilitators, and strategies for successful KT of EBP, EI, or RU across disciplines. We included articles regardless of discipline because KT implementation strategies are valued and transferable across sectors. We excluded conference abstracts and letters or editorials, as well as articles that did not explicitly analyze KT, EI, or RU.

Screening process

One author assessed titles and abstracts of identified articles to determine eligibility. Articles deemed potentially relevant underwent full-text review by the same author. The rest of the working group confirmed inclusion of each full-text article.

Data extraction

Descriptive information was extracted from included full-text articles (i.e., first author, year of publication, field/ discipline, and barriers and facilitators to KT, EI, or RU). Extracted data were summarized and presented in tabular form and grouped within overarching themes of KT, EI, and RU barriers and facilitators from the reviewed literature by one reviewer. Each barrier and facilitator were also categorized according to whether KT was influenced by individuals alone, the collegial/peer relationship, or organizations/ institutions for recommendations by the same reviewer. The data extraction table underwent independent review among the full working group, and required unanimous consensus among the full group.

Data analysis and development of recommendations

Recommendations were developed and proposed individually via e-mail by members of the working group. All recommendations required unanimous consensus to be approved, which was achieved through iterative discussions among the working group, also via e-mail. The recommendations were focused specifically on what professional associations and similar organizations could do to support their members’ KT, EI, and RU needs and responsibilities.

Results

Of 1,432 articles identified in database searches, 45 were included in our review (Appendix 2). Included articles encompassed 20 unique health related disciplines with each providing insights into KT and offering barriers and/ or facilitators to the effective integration of evidence into clinical practice (Apendix 3).

Barriers and facilitators to KT

Figure 2 We found many key determinants of KT in the reviewed literature that are relevant to community-based chiropractors (Appendix 3), and categorized these into three levels:

(1) individual practitioner [7-32],

(2) collegial/peer community [7, 12, 14, 16–18, 20, 23-25, 30, 32-44], and

(3) institutional/organizationa [7, 8, 10-20, 23, 25-28, 31-35, 37, 38, 40-42, 44-51] (Figure 2).Regardless of the field of practice, determinants of knowledge translation (KT), evidence integration (EI), and research utilization (RU) in practice were found to share commonalities.

Level 1: Barriers and facilitators to KT for the individual practitioner

At the individual level, we identified barriers and facilitators to KT in the reviewed literature that influenced a practitioner’s and/or researcher’s ability to engage in KT initiatives (Appendix 3).Barriers

Without adequate training (and/or time to train) in research methods and KT implementation, practitioners across fields often lack the confidence and ability necessary to assess and appropriately translate research into practice. [7, 9, 10, 13, 20, 22, 28, 29, 32] One systematic review investigating KT of health research found that insufficient critical appraisal skills and difficulty in understanding and applying research among clinicians were major barriers to KT. [10] This issue was also raised in veterinary medicine, in that practitioners tend to focus on journal abstracts rather than the full-text articles, which prevents them from gaining a deeper understanding of the findings and methods described in the parent article. [9] A scoping review exploring uptake of new research and technologies in neurorehabilitation identified that steep learning curves associated with applying new findings or technologies in research also pose barriers to KT, exacerbating challenges of limited research training and KT skills. [20] Moreover, chiropractic literature adds that time constraints faced by practitioners hinders robust dissemination of research into practice, posing challenges to KT regardless of a clinician’s KT knowledge, skill, or attitudes. [7, 11]

Research involving the disciplines of health policy and physical rehabilitation has identified that tensions within researcher-clinician interactions further serve as a barrier to effective knowledge translation (KT), evidence integration (EI), and research utilization (RU) at the individual level. [30, 31] In particular, research investigators often develop robust programs of research; however, clinicians face challenges with applying research results to the realities of clinical practice and individual patient circumstances. [30, 31] Contextually, these tensions can sometimes arise as a consequence of investigators making recommendations based on ideal circumstances (e.g., carefully calibrated characteristics and inclusion criteria for research participants in fastidiously conducted clinical trials), as compared with the imperfect and uncalibrated realities faced by practitioners serving patients in clinical practice. [30] Moreover, poor methodological rigour of studies, lack of standardized outcome measures, and feasibility issues for implementing results (e.g., lengthy protocols for clinicians to follow), have additionally been shown to hinder uptake of research into practice. [15, 44] A survey of Swiss chiropractors further indicated that a perceived lack of clinical evidence in the chiropractic field itself contributed to limited application of research findings in daily practice. [11]

Facilitators

Research in occupational therapy and physiotherapy education suggests that collaboration between academic faculty, clinical preceptors, researchers, clinicians, and patients in classroom settings can enhance EBP and KT competencies among individual students. [16] Findings from a mixed methods study by Roberge-Dao et al. showed that involving clinicians at the start of a research project’s conceptualization, as well as throughout the research process, can help improve the external validity of the results and the likelihood of their implementation in practice. [30] Provider internal motivation and willingness to learn have also been shown to be major facilitators for uptake of research and implementation of EBP among individual practitioners in nursing. [10, 24]

As suggested in academic and education-related literature, individual level barriers to KT can be balanced by formal institutional recognition of the value of KT work, and the opportunity for researchers to build a reputation in KT, beyond academic publishing, to enhance career development. [19, 31] This could incentivize and personally motivate researchers and practitioners alike to overcome barriers to KT at the individual level, and promote better research culture and implementation in general. [19, 31] A scoping review investigating KT of EBP practices within cerebral palsy care highlights how protected, or compensated, time for individual clinicians to engage with research facilitates KT and implementation of EBP. [17] Others have similarly shown that compensated ‘release time’ for clinicians to engage in KT activities effectively facilitates KT. [23]

Research findings themselves can also offer potential incentives for KT. [25] For example, a qualitative study involving Swiss pharmacists and clinicians found that when research favoured implementation of pharmacist/clinician services that had potential to offer economic value to these practitioners, it facilitated uptake of the research findings into clinical practice. [25]

Level 2: Barriers and facilitators to KT for the collegial/peer community

We found several variables in the reviewed literature that influence effective KT at the collegial/peer community level (Appendix 3). In particular, we identified several facilitators that can help overcome common barriers surrounding KT initiatives.Barriers

Lack of interpersonal skills or physical proximity represent the major barriers to effective KT at the collegial/peer community level. These can lead to limited interdisciplinary collaboration, which has been shown to hinder implementation of care services that are beneficial to patients. [25] A difficult or poor work culture in which colleagues/peers show resistance to change has also been shown to hinder uptake of new findings or methods. [12, 14] Due to the collaborative nature of work involving the interdisciplinary and public health fields, literature in these areas offer a unique context for overcoming barriers to effective KT, [35, 36, 43] as described below.

Facilitators

Findings from both interdisciplinary and public health research suggest that early engagement with stakeholders facilitates KT at the collegial/peer community level by ensuring research is tailored to the end-user. [36, 38, 43] Moreover, the use of effective knowledge brokers (e.g.., intermediary organizations or persons) to disseminate research or engage stakeholders in collaborative training activities can facilitate evidence-informed decision-making for institutions and clinicians, as well as increase understanding for patients and the public. [17, 18, 30, 35, 43] Reviewed literature further suggests that researchers, policy-makers, and practitioners across disciplines must engage in collaborative efforts to enhance their KT abilities. [8, 30, 32, 35, 36, 38–43] Such efforts contribute to acquired collaborative skills and strengthened partnerships among those involved in the care and research process, further facilitating KT. [34, 35, 43] Members of multidisciplinary teams, given their unique position to perceive contextual barriers across disciplines, also play a major role in facilitating collaborations and advancing KT. [52]

Another major facilitator of collaboration and KT at the collegial/peer community level is physical proximity (e.g., shared office or clinic space). [23, 30, 32] Close physical proximity enables more frequent, engaging, and in-person conversations allowing for the sharing of motivations for engaging in KT work and skills development. [30, 32] Conversations among practitioners in particular help frame individual clinical projects (e.g., sharing of patient cases, study findings, lectures, etc.) within the broader context of research, fostering an understanding that each project is a part of a larger initiative. [30, 36] Moreover, close physical proximity between researchers and clinicians facilitates researcher and knowledge-user interaction and collaboration, further promoting KT. [23]

Collaborative dialogue among KT stakeholders depends on a strong ‘top-down’ organizational culture valuing KT, EI, and RU. [37] In the nursing profession, for example, nurses are seen as integral members of care teams, and research utilization in practice depends on access to electronic resources, organizational support for KT-related skills development, and a culture that values continuous learning. [37] A qualitative study of program directors in medical education also found that easy access to summaries, reviews, and guidelines of primary research, facilitated use of research within the field. [14] Some studies further suggest that mentorship programs are effective strategies in facilitating KT (e.g., supportive KT “champions”), bridging knowledge-practice gaps and fostering collaboration among different generations. [7, 12, 14, 17, 24, 33, 39, 52]

Level 3: Barriers and facilitators to KT at the institutional/organizational level

At the institutional/organizational level, the main barriers and facilitators to KT that we identified in the reviewed literature included factors that either supported or restricted KT initiatives at the individual or collegial/peer community level (Appendix 3).Barriers

Lack of funding is a key barrier for KT at the institutional level. For funding to most effectively enable KT, it is necessary to be geared by way of policy to KT, EI, and RU as well as align with the researchers’ and institutions’ goals and priorities. [47, 48] However, developing and maintaining continuity and motivation in funding partnerships is a challenging and intensive process, hence there is a need for institutions to establish KT leaders within their organization to maintain engagement with all stakeholders, including funding agencies. [48, 51] A lack of funding and/ or institutional restrictions have been demonstrated in the literature to be major organizational barriers to optimal KT. [45] Professional associations, educational institutions, funding agencies, and organizations therefore play an important role in shaping the culture of KT, EI, and RU within practitioner communities. [46] This is particularly done through policy adoption and creating an environment that values KT. [26, 53]

Facilitators

A national environmental scan found that demonstrable institutional support and advocacy for practitioners to engage collaboratively with literature was needed to address barriers of evidence-informed healthcare and KT. [38] In particular, institutional backing demonstrated through policies mandating dedicated time for literature review, organizing educational events, and promoting research literacy was suggested in the scan to set the tone for KTA priorities. [38] Organizational supports provided within these expectations included opportunity for building capacity and networks to participate in KT activities, sharing accessible evidence, education, training, motivation/ incentives, and enabling researchers to carry out KT activities. [38] Additional literature suggests that tailored capacity building, education, and training sessions for KT purposes offered by organizations in particular, should be recommended across disciplines to bolster KT. [7, 12, 16, 17, 19, 20, 28, 33, 37, 38, 45, 50] Certain disciplines such as dementia care and neurorehabilitation recommend continuous learning and aligning methods with KT goals, learner preferences, and workplace dynamics to facilitate optimal KT knowledge, skills, and implementation, as well as sustainability and effectiveness of KT. [19, 20, 33, 38]

The reviewed literature also suggested that institutional-level actors are positioned to develop key messaging around KT, EI, and RU that resonates with diverse populations that access the institutions’ resources. [19, 34] Resources that are dedicated to ensuring the utilization of evidence in practice, such as free educational materials, access to critical reviews, full-text articles and support for RU in practice necessitates leadership, with a commitment to outcomes of KT-advancing initiatives. [7, 27, 38, 50] This requires developing and allocating these resources for staff to foster a culture conducive to effective KT [10–13, 18, 23, 33, 38, 46], as well as ensuring all resources are easily accessible. [8, 14, 28, 37, 50] Medicine-based literature suggests that institutions should also provide practitioners with pre-digested, trusted information, and paid time in daily practice devoted to systematic reading of clinical journals. [27] By providing these resources, organizations can optimize staff time, and improve confidence and ability in effectively translating research into practice. [28, 37, 50] Additional resources for facilitating KT at the institutional level include continuing education workshops and opportunities for networking with researchers. [10, 16, 17, 23] Organizations can offer incentives to their members for engaging in KT work [31, 32, 40–42], as a lack of KT incentives has been demonstrated to restrict KT in the chiropractic literature. [7]

Engaging knowledge-users (e.g., clinicians) in the research process was also found in our review as a key facilitator of KT in practice, particularly when building consensus around policy issues. [35, 41, 54] Institutions can contribute to this by fostering collaboration among stakeholders. [10, 35, 41, 54] An institution’s ability to have well-placed and credible KT researchers helps to facilitate KT activities through the effective installation of leaders who can facilitate and develop strategies to champion KT initiatives and motivate practitioners to join and participate meaningfully. [12, 14, 17, 49] Individuals with such KT expertise would also be able to assist with informing funding agencies to ensure proper allocation of resources, maximizing KT benefits of EBP. [49]

Actioning review findings: context and recommendations Context

The evolution of the historical boundaries between the public and private health systems in Canada is significant in context, shaping both the nature and level of institutional support for research and KT in these parallel but entangled systems. In the public single-payer system, data collection is centralized at the provincial level and is used to set the strategic direction of payment policy to drive clinical practice improvements and support for research. [55] KT is further supported by physical and social infrastructures characteristic of interprofessional team environments in, for example, hospitals, family health teams, and community health centres.

The situation for community-based private practice is substantially different, and this difference matters for how we conceptualize, plan for, and support KT initiatives in the chiropractic profession. For example, in Ontario, there are some 5,120 licensed chiropractors, [56] ~3,944 of which are members of the OCA. According to market research undertaken by the OCA in 2019, approximately 80% of the chiropractic care delivered is paid for through the private health insurance system, [57] primarily employer-sponsored plans. Though the market in Canada is dominated by a small number of large companies, there are over 160 insurance providers. [58] This results in a high degree of fragmentation and proprietary ownership of data collected by payors and clinics. This largely for-profit context does not have the same drivers of change as a public-payer system.

With respect to research funding, the CIHR has an annual budget of approximately $1 billion allocated across four pillars, which are (understandably) reflective of the priorities of the public system: (1) biomedical; (2) clinical; (3) health systems services; and (4) population health. [59] While research related to chiropractic practice fits within these pillars and does get funded, musculoskeletal (MSK) research related to rehabilitation and prevention does not get as much attention as other priority areas. By contrast, the major funder of chiropractic research in Canada is a private foundation, the Canadian Chiropractic Research Foundation (CCRF) (https://canadianchiropracticresearchfoundation.ca/). The CCRF relies on contributions from individuals, charities, and, in large part chiropractors themselves, via their membership dues in their provincial associations. Over a three-year span up until 2021, the CCRF provided just under $900,000 in grants to support chiropractic research. [60] However, both CCRF and CIHR funding are highly competitive and difficult to access. In 2021, for example, the average size per CIHR grant was $770,000 (CAD) over four years, with only a 17% success rate. [61] Moreover, the CCRF placed a recent funding cap of $25,000 on individual projects and no longer funds chiropractic university-based research chair positions, further limiting access to Canadian chiropractic research funding and support. Thus, there is an opportunity for chiropractic associations to collaborate with research and teaching institutions to monitor the research funding landscape with the aim of supporting chiropractic researchers, and especially early career researchers, to access the diverse sources of funding available. [62] In the Ontario environment these would also include the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), and Mitacs. However, to access government grants, chiropractic researchers need to hold a faculty position at an academic institution or be directly affiliated with one of the few chiropractic researchers who does. [62] Accordingly, if the chiropractic profession wishes to compete for large research grants and keep pace with other healthcare professions, there needs to be support for university-based faculty positions for chiropractic researchers.

Given this context, while chiropractic clinicians have a responsibility to provide care that is based on the best available evidence, they need support for all aspects of KT, EI, and RU. Our next section of this paper identifies the opportunities and responsibilities for associations like the OCA to support KT for their members. The recommendations made here are done in accordance with the KT facilitators identified in our literature review.

Table 1

page 10Recommendations

A summary of our recommendations made based on the findings of this review, along with actionable steps corresponding to each recommendation can be seen in Table 1.

Recommendations: the individual

At the individual level, chiropractors have a responsibility to seek out the best available research evidence and hone the necessary skills for integrating this evidence into their treatment plans with patients. [9, 26, 27, 45] Clinicians should seek to create time and space for learning and development of research literacy and critical appraisal skills to gain the confidence required to apply research in context. [9–12, 16, 17, 23, 26, 27, 45] This should include developing an understanding of core KT competencies [26] and use of specific organizational resources. [26] Clinicians at all career stages can seek out and contribute to supportive professional learning environments, for example, through participation in mentorship and preceptorship programs [7, 33, 39, 52], or by leading or attending webinars, lunch-and-learns, or networking events. [10, 16, 17, 23, 30, 32, 43] This also includes participation in research, whether as a study clinician collecting data from patients, or being involved within the core author group through study development and completion. [8, 30, 35, 41] Clinicians should also advocate on behalf of themselves and the profession for improved supports.

Recommendations: collegial/peer community

At the collegial/peer community level, key recommendations include creating supportive environments for mentorship and modelling of inter-generational learning, [7, 33, 39, 52] as well as opportunities for hands-on application of putting evidence into practice. [30, 32, 43] Close locational proximity to colleagues and collaborators will help to facilitate this. [23, 30, 32, 43] Given many practitioners in Ontario are in solo practice, organizations such as professional associations could establish or support practice communities in specific geographic areas (e.g., local chiropractic societies or clusters) or across areas of professional interest and expertise. Opportunities for networking to meet with colleagues and researchers to share in substantive KT conversations could improve morale and attitudes regarding KT, EI, and RU, and could be facilitated at the organizational level through the sponsorship of in-person and virtual events. [30,32,43]

Organizations could devote resources to keeping abreast of leaders in clinical research and KT, and facilitate access to these people and groups for “rank and file” clinicians. [48, 49, 51] This may include provision of human resources in KT, financial resources (e.g., providing salary support for a KT champion), and incentivized clinician time. [49] Organizations can also support KT at the collegial/peer community level by promoting conversation and collaboration. [35, 43] For example, this might be accomplished by engaging with knowledge brokers to disseminate research [17, 18, 35] and stakeholders (e.g., clinicians, researchers, patients) to participate in collaborative training activities, [10, 16, 18, 43] or promoting regular dialogue with their members and affiliates on research priorities to inform research investments. Organizations should also facilitate collaboration among researchers and field practitioners to ease noted tensions (or misunderstandings) between the two groups, which will further facilitate KT in clinical practice. [8, 30, 35, 41]

Recommendations: institutional/organizational

At the institutional/organizational level, professional organizations and associations like the OCA are leaders for their membership and, therefore, their values, goals, and mandates serve as a model for those of their professional members and associated research communities. The importance of KT, EI and RU should therefore be reflected at the organizational level as a core aspect of strategic planning, for example, and of formal reporting and other communications to members and stakeholders. [26, 38, 46] This includes implementing institutional recognition for practitioner contributions to KT and research [19, 31, 32, 40–42], such as through mentor or preceptor awards or certifications. Engagement with the expertise of recognized specialties within the profession, as well as fostering new specialties, could further advance this goal. [49]

For example, organizations could allocate dedicated funds to support KT specialists (e.g., knowledge-brokers) to engage with community practitioners. [35] Furthermore, organizations can model the culture of KT via a focus on evaluation and continuous learning in their own programs and initiatives [37], such as through impact evaluations. The OCA and other chiropractic associations can sponsor or organize conferences, seminars, webinars, workshops and other educational platforms to enhance learning opportunities for KT [7, 19, 28, 33, 37, 38, 45, 50], ensuring robust scientific validity through careful vetting of presentations and presenters.

In the Ontario environment, the OCA has developed an electronic patient record and practice management platform, called “OCA Aspire,” [63] that allows for the integration of evidence-based pathways into care planning. This platform will assist in transforming both the physical and temporal availability of evidence and best practices, and enable care plan adherence and outcome monitoring. Longer term, the OCA Aspire platform also has significant potential to address issues of data ownership and fragmentation. This could, for the first time, allow individual practitioners and researchers in Ontario (and beyond) to have access to centrally aggregated de-identified data specific to the chiropractic profession, generated through daily encounters with patients logged in electronic health records across the province. Such data could be used to inform future clinical trial research (i.e., higher quality evidence), to support the development of robust clinical guidelines for conditions commonly seen within the chiropractic scope.

Chiropractic organizations might also support KT by developing incentives [9, 42, 43, 51, 64–66] tied to healthcare providers’ overhead costs, such as membership fees or administrative costs. For example, healthcare professionals could earn reward points or credits for continuing professional development (CPD) hours with substantial KT, EI or RU elements, which could then be used for discounted membership fees. Likewise, organizations including associations and regulatory bodies have an important role to play in the adoption and enforcement of policy and incentives for affording practitioners the time during business hours to collaboratively engage with KT in clinical practice. [19, 31] Recognition for mentorship and preceptorship would likewise be contingent on the demonstration of successful role modelling of EI and RU in practice with student interns in clinic. In addition, chiropractic organizations could provide pre-digested and trusted information sourced from recent relevant literature to chiropractors to be considered for implementation into practice. [27] These recommendations all target the need for dedicated time and resources for clinicians to engage in KT, EI, and RU. [7, 9, 27–29, 32]

Discussion

In this paper we aimed to summarize key determinants of KT across disciplines and offer actionable recommendations to improve uptake and application of EBP in routine chiropractic care. We identified KT barriers and facilitators at three levels: (1) individual practitioner, (2) collegial/peer community, and (3) institutional/organizational, in alignment with previous findings. [45] Articles included in our review spanned multiple disciplines. Regardless of the field of practice, we found that barriers and facilitators to KT, EI, and RU in practice shared commonalities, largely because human practitioners were the research users in every case.

Importantly, knowledge translation (KT), evidence integration (EI), and research utilization (RU) require human research users to become informed, skilled, collaborative, and pragmatic implementers of the best available evidence. The values, supports, and resources attributed to KT require active participation of actors at all three aforementioned levels (i.e., individual, collegial, and institutional), and the efforts and abilities of individual practitioners should be intertwined with organizational RU and EI values, cultures, expectations, attitudes, and opportunities to engage in KT work.

In the chiropractic profession, barriers exist at the individual level regardless of how strongly a practitioner believes in EBP. [2, 11, 64, 66] For instance, chiropractors report “positive attitudes” toward EBP, yet uptake of research into practice, as measured by the use of clinical practice guidelines, is less favourable even when clinicians express confidence in the ability to identify clinically relevant research. [2, 64, 66] This suggests that chiropractors may be more comfortable consuming research than integrating evidence into clinical practice, which requires additional skill, collaboration, mentorship, and institutional resources, all of which have been identified in the literature as being significant influencers of KT.

Chiropractors’ difficulties in integrating evidence into practice may be exacerbated by tensions within researcher-clinician interactions. [30, 31] A mixed methods study in physical rehabilitation suggested that tensions develop when researchers provide recommendations that are not easily generalizable to ‘real-world’ practice.30 In the 2004 UK BEAM trial [67], for example, 89% of the 11,929 back pain patients identified were either unavailable or excluded prior to randomization, thereby reducing the study’s generalizability to a niche low back pain population. In line with reviewed literature, we recommend engaging knowledge-users in the research process to facilitate KT in clinical practice, as well as to build consensus around policy issues. [30, 35, 36, 38, 41, 43, 54]

A lack of time, shown to impact individual, collegial/ peer community, and institutional/organizational levels, also likely contributes to limited research uptake into chiropractic practice. [2, 11, 64, 66] Several chiropractic surveys indicate that clinicians report “lack of time” as the most common barrier to developing their EBP skills, despite being interested in improving them. [64, 65] In line with our review, this perceived lack of time amongst clinicians can create significant barriers to KT, including a lack of confidence or ability to locate, interpret, and critically appraise research to apply in clinical practice. [7, 32, 40, 41] As such, organizational provision of training, resources, and pre-digested information to chiropractic clinicians, as well as incentivizing time dedicated to KT (e.g., through reduced membership fees), could enhance KT in the chiropractic profession, particularly because clinicians’ attitudes appear to already be favourable toward EBP. Furthermore, in addition to academic journals, knowledge dissemination should occur through additional outlets, including those focusing on community-based providers (e.g., chiropractic opinion leaders) to further bridge the KTA gap. [11, 66, 68]

Regardless of strategy, effective KT approaches require flexibility to account for varying clinical and local contexts, [69] and must be tailored to overcoming barriers to knowledge use identified in those contexts. KT efforts often fail when KT barrier assessments are not conducted, or KT interventions/implementation strategies are not aligned. Assessments of barriers should therefore be comprehensive, and assessed using frameworks such as the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) or Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). [70, 71] Additional frameworks such as the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation – Behaviour (COM-B) model can then be used to design KT interventions tailored to address locally identified KT barriers. [21, 72] To optimize time and resources in the chiropractic profession, individual practices and chiropractic organizations should assess KT barriers unique to their context, in light of the broader stakeholder and policy landscape. [73]

Overall, the reviewed literature suggests that institutions/ organizations play a major role in facilitating KT, as they can cultivate the landscape for KT, EI, and RU culture through their strategic priorities, values, and allocation of resources. In line with our recommendations, organizations can offer sponsorship of in-person and virtual events, devote resources to developing and maintaining leaders in research and KT, and reflect the importance of KT as a core aspect of strategic planning, formal reporting and other communications to members and stakeholders. [8, 10–14,16–18, 20, 23, 28–31, 40, 41, 46–48,51] Organizations can also incentivize practitioners by affording them time during business hours to engage with the research literature, as well as with their colleagues, and collaborate on ways to implement the best available evidence into clinical decision-making. [19, 31]

Implications for patient outcomes

Integrating best evidence into clinical practice can enhance care quality and patient outcomes (e.g., more effective pain relief, greater functional improvement). [39, 74] KT strategies that promote active patient engagement and education have also been shown to result in higher levels of satisfaction, improved adherence to treatment plans, and reduced reliance on opioid prescriptions. [74, 75, 76, 77] As such, the strategic implementation of KT in clinical practice is essential for healthcare providers in delivering higher-quality, effective, safe, patient-centred care.

Limitations

This narrative review has several limitations that are inherent to its design. First, we did not use a systematic search strategy or formal risk of bias assessments, as the goal was to broadly capture literature on KT, EI, and RU from multiple disciplines to inform chiropractic practice rather than to exhaustively review all possible evidence. In narrative reviews, this flexibility can allow for the integration of diverse sources and perspectives, which may be valuable for generating actionable insights. Additionally, only one reviewer initially conducted screening and data extraction, posing bias risk that some authors may have included articles this reviewer excluded in the screening process. However, final inclusion and data extraction of studies was reviewed by the full working group, helping to ensure a broader validation of included studies.

Another limitation is that only English-language articles were included, which may have excluded relevant studies published in other languages. However, given the quantity of literature returned in our searches published in English, we expect that the key findings and recommendations are still well represented. Additionally, the selected timeframe (January 1, 2016, to August 1, 2024) may have limited the findings to recent literature, potentially overlooking studies with relevant insights published prior to 2016. However, this timeframe was chosen to extend the foundational insights from the 2016 landmark scoping review by Bussières et al. [7], allowing us to build on previous work while focusing on contemporary barriers and facilitators that are directly applicable to today’s clinical environment.

Finally, we did not employ a formal consensus method (e.g., Delphi or nominal group technique) to develop recommendations. Instead, recommendations were derived through iterative discussions among the working group, composed of chiropractors, researchers, and educators with relevant expertise. While this informal consensus process may limit reproducibility, it allowed for practical, context-specific recommendations tailored to the needs of community-based chiropractic practice. Future research could enhance rigor by employing systematic review methodologies, including studies from multiple languages, expanding the timeframe, and using formal consensus methods, such as Delphi panels, to further validate and refine recommendations.

Strengths

This review contributes valuable, context-specific insights that address the practical needs of KT within chiropractic care. By tailoring its focus to the unique barriers and facilitators relevant to community-based chiropractic practice, the review offers recommendations that are directly applicable to clinicians and professional organizations in this field. While it does not introduce new theoretical frameworks, the review fills a gap by providing discipline-specific guidance for chiropractors, a group often underrepresented in broader KT literature. Additionally, the inclusion of cross-disciplinary perspectives enriches the findings, as KT strategies validated in other healthcare disciplines are adapted here for use in chiropractic practice, promoting a more integrated approach. Recognizing the time constraints of busy practitioners, the review emphasizes accessible and practical recommendations, making the KT process more manageable for chiropractic professionals. This flexible approach allows for the integration of recent and relevant literature, which supports actionable steps that can be feasibly implemented in real-world settings.

Future directions

Future research could expand on this review by incorporating primary data collection methods, such as interviews or surveys, to gather in-depth insights from individual practitioners, peer groups, and institutions. Such studies could further explore perspectives on and engagement with knowledge translation (KT), evidence integration (EI), and research utilization (RU) initiatives within chiropractic care. Additionally, examining the views and experiences of various stakeholders — ranging from clinicians to organizational leaders — would enhance understanding of the factors that support or hinder KT efforts, potentially leading to more targeted and effective strategies.

Conclusions

Knowledge translation (KT) through evidence integration (EI) and research utilization (RU) in clinical practice is a collaborative endeavour between clinicians and their stakeholder ecosystem. Professional organizations and associations must not only adopt policy and model their value of KT, EI, and RU, but also clearly demonstrate their commitment to improving patient outcomes by equipping their membership with the tools and resources they need to succeed in developing the required skills, research literacy, and confidence for the most effective implementation of KT. The structural significance of professional organizations, regulators and associations cannot be understated, since structural reform has a widespread and influential trickle-down effect for practitioner-members and the patients they care for.

Actionable steps we feel that professional organizations, associations, and funding agencies should take include, but are not limited to:(1) allocating funding to EI and RU implementation initiatives;

(2) adopting policy that encourages and incentivizes KT (i.e., paid time during business hours to develop clinicians’ KT skills and practical strategies for implementation of EI and RU);

(3) developing institution-based and institution-wide mentorship programs that support and prioritize inter-generational mentorship, modelling, and collaboration; and

(4) offering programs to facilitate KT using various educational platforms. Practitioners would also benefit from formal, professional, career advancing recognition of their KT implementation work.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 1. (see p. 18) Search terms and phrases

Appendix 2. (see p. 19) Flowchart diagram showing the search and selection process of studies included in this review.

Appendix 3. (see p. 20) Included papers from our database searches that identify barriers, facilitators and strategies for successful KT of EBPAcknowledgments

Acknowledgements for this paper, and for the entire JCCA special edition, are listed and detailed within the Preface paper.

Conflicts of Interest

This research was funded by the OCA. The lead authors received a per diem for their work on this project. The authors declare no other conflicts of interest, including no disclaimers, competing interests, or other sources of support or funding to report in the preparation of this manuscript.

References:

Haynes RB, Devereaux PJ, Guyatt GH.

Clinical expertise in the era of evidence-based

medicine and patient choice.

Evid Based Med. 2002;7(2)Walker BF, Stomski NJ, Hebert JJ, French SD.

Evidence-based practice in chiropractic practice: A survey of

chiropractors’ knowledge, skills, use of research

literature and barriers to the use of research evidence.

Complement Ther Med. 2014;22(2):286–295.

doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2014.02.007.Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR)

About us: Knowledge translation at CIHR. 2016.

Available from: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29418.htmlGraham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, et al.

Lost in knowledge translation:

time for a map?

J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(1):13–24.

doi: 10.1002/chp.47.Tetroe J, Graham I, Foy R, Robinson N, Eccles M, Wensing M, et al.

Health research funding agencies’ support and promotion

of knowledge translation: an international study.

Millbank Q. 2008;86(1):125–155.

doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00515.x.Kawchuk G, Bruno P, Busse J, Bussières A, Erwin M, Passmore S, et al.

Knowledge Transfer Within the Canadian Chiropractic

Community Part 1: Understanding Evidence-Practice Gaps

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2013 (Jun); 57 (2): 111–115Bussières AE, Zoubi F, Al Stuber K, French SD, Boruff J, et al.

Evidence-based Practice, Research Utilization, and

Knowledge Translation in Chiropractic: A Scoping Review

BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016 (Jul 13); 16 (1): 216Mwendera CA, de Jager C, Longwe H, Phiri K, Hongoro C.

Facilitating factors and barriers to malaria research

utilization for policy development in Malawi.

Malar J. 2016;15(1):512.

doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1547-4Keay S, Sargeant JM, O’Connor A, Friendship R.

Veterinarian barriers to knowledge translation (KT)

within the context of swine infectious disease

research: an international survey

of swine veterinarians.

BMC Vet Res. 2020;16(1):416.

doi: 10.1186/s12917-020-02617-8.Abu-Odah H, Said NB, Nair SC, Allsop MJ, Currow DC, Salah MS, et al.

Identifying barriers and facilitators of translating

research evidence into clinical practice:

a systematic review of reviews.

Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30(6):e3265–3276.

doi: 10.1111/hsc.13898.Albisser A, Schweinhardt P, Bussières A, Baechler M.

Self-reported Attitudes, Skills and Use of Evidence-based

Practice Among Canadian Doctors of Chiropractic:

A National Survey

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2015 (Dec); 59 (4): 332–348Cassidy CE, Flynn R, Campbell A, Dobson L, et al.

Knowledge translation strategies used for sustainability

of an evidence-based intervention in child health:

a multimethod qualitative study.

BMC Nurs. 2024;23(1):125.

doi: 10.1186/s12912-024-01777-4Dam JL, Nagorka-Smith P, Waddell A, Wright A, Bos JJ, Bragge P.

Research evidence use in local government-led public

health interventions: a systematic review.

Heal Res Policy Syst. 2023;21(1):67.

doi: 10.1186/s12961-023-01009-2Doja A, Lavin Venegas C, Cowley L, Wiesenfeld L.

Barriers and facilitators to program directors’ use

of the medical education literature:

a qualitative study.

BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):45.

doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03104-4Edwards JD, Dominguez-Vargas AU, Rosso C, Branscheidt M, et al.

A translational roadmap for transcranial magnetic and

direct current stimulation in stroke rehabilitation:

Consensus-based core recommendations from the

third stroke recovery and rehabilitation roundtable.

Int J stroke Off J Int Stroke Soc. 2024;19(2):145–157.

doi: 10.1177/17474930231203982Hallé MC, Bussières A, Asseraf-Pasin L, Storr C, et al.

Stakeholders’ priorities in the development of

evidence-based practice competencies in

rehabilitation students: a nominal

group technique study.

Disabil Rehabil. 2024;46(14):3196–3205.

doi: 10.1080/09638288.2023.2239138Hanson J, Sasitharan A, Ogourtsova T, Majnemer A.

Knowledge translation strategies used to promote

evidence-based interventions for children with

cerebral palsy: a scoping review.

Disabil Rehabil. 2024:1–13.

doi: 10.1080/09638288.2024.2360661Kerr C, Novak I, Shields N, Ames A, Imms C.

Do supports and barriers to routine clinical

assessment for children with cerebral palsy

change over time? A mixed methods study.

Disabil Rehabil. 2023;45(6):1005–15.

doi: 10.1080/09638288.2022.2046874Phillipson L, Goodenough B, Reis S, Fleming R.

Applying Knowledge Translation Concepts and

Strategies in Dementia Care Education

for Health Professionals.

J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2016;36(1):74–81.

doi: 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000028Murphy M, Pradhan S, Levin MF, Hancock NJ.

Uptake of Technology for Neurorehabilitation

in Clinical Practice: A Scoping Review.

Phys Ther. 2024;104(2)

doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzad140Presseau J, Kasperavicius D, Rodrigues IB, Braimoh J, et al.

Selecting implementation models, theories, and

frameworks in which to integrate

intersectional approaches.

BMC Med Res Methodol. 2022;22(1):212.

doi: 10.1186/s12874-022-01682-xSzmaglinska M, Andrew L, Massey D, Kirk D.

Exploring the Underutilized Potential of Clinical

Hypnosis: A Scoping Review of Healthcare

Professionals’ Perceptions,

Knowledge, and Attitudes.

Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2024;72(2):109–138.

doi: 10.1080/00207144.2023.2276451Kengne Talla P, Robillard C, Ahmed S, Guindon A, Houtekier C.

Clinical research coordinators’ role in knowledge

translation activities in rehabilitation:

a mixed methods study.

BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):124.

doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09027-0Thürlimann E, Verweij L, Naef R.

The Implementation of Evidence-Informed Family

Nursing Practices: A Scoping Review of

Strategies, Contextual Determinants,

and Outcomes.

J Fam Nurs. 2022;28(3):258–276.

doi: 10.1177/10748407221099655Wiss FM, Jakober D, Lampert ML, Allemann SS.

Overcoming Barriers: Strategies for Implementing

Pharmacist-Led Pharmacogenetic Services in

Swiss Clinical Practice.

Genes (Basel) 2024;15(7)

doi: 10.3390/genes15070862Mallidou AA, Atherton P, Chan L, Frisch N, Glegg S, Scarrow G.

Core knowledge translation competencies: a scoping review.

BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):502.

doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3314-4Vaucher C, Bovet E, Bengough T, Pidoux V, Grossen M, et al.

Meeting physicians’ needs: a bottomup approach for

improving the implementation of medical

knowledge into practice.

Heal Res Policy Syst. 2016;14(1):49.

doi: 10.1186/s12961-016-0120-5DeLeo A, Bayes S, Geraghty S, Butt J.

Midwives’ use of best available evidence in practice:

An integrative review.

J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(23–24):4225–4235.

doi: 10.1111/jocn.15027Bennett S, Allen S, Caldwell E, Whitehead M, et al.

Organisational support for evidence-based practice:

occupational therapists perceptions.

Aust Occup Ther J. 2016;63(1):9–18.

doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12260Roberge-Dao J, Yardley B, Menon A, Halle MC, et al.

A mixed-methods approach to understanding partnership

experiences and outcomes of projects from an

integrated knowledge translation funding model

in rehabilitation.

BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1)

doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4061-xCollie A, Zardo P, McKenzie DM, Ellis N.

Academic perspectives and experiences of knowledge

translation: A qualitative study of public

health researchers.

Evid Policy. 2016;12(2):163–182Tait H, Williamson A.

A literature review of knowledge translation and

partnership research training programs for

health researchers.

Health Res Pol Syst. 2019;17

doi: 10.1186/s12961-019-0497-zGénéreux M, Lafontaine M, Eykelbosh A.

From Science to Policy and Practice: A Critical

Assessment of Knowledge Management before,

during, and after Environmental

Public Health Disasters.

Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(4):587.

doi: 10.3390/ijerph16040587Cameron J, Humphreys C, Kothari A, Hegarty K.

Exploring the knowledge translation of domestic

violence research: A literature review.

Health Soc Care Community. 2020;28(6):1898–1914.

doi: 10.1111/hsc.13070McGinty EE, Siddiqi S, Linden S, Horwitz J.

Improving the use of evidence in public health

policy development, enactment and implementation:

a multiple-case study.

Health Educ Res. 2019;34(2):129–144.

doi: 10.1093/her/cyy050Verville L, Cancelliere C, Connell G, Lee J, Munce S, et al.

Exploring clinicians’ experiences and perceptions

of end-user roles in knowledge development:

a qualitative study.

BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):926.

doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06955-7Grant A, Coyer F.

Contextual factors to registered nurse research

utilisation in an Australian adult metropolitan

tertiary intensive care unit:

A descriptive study.

Aust Crit Care. 2020;33(1):71–79.

doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2019.01.001Glegg SMN, Ryce A, Miller KJ, Nimmon L, Kothari A, Holsti L.

Organizational supports for knowledge translation in

paediatric health centres and research institutes:

insights from a Canadian environmental scan.

Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2(1):49.

doi: 10.1186/s43058-021-00152-7Montpetit-Tourangeau K, Kairy D, Ahmed S, Anaby D, et al.

A strategic initiative to facilitate knowledge

translation research in rehabilitation.

BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1)

doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05772-8Jakobsen MW, Karlsson LE, Skovgaard T, Aro AR.

Organisational factors that facilitate research use

in public health policy-making: a scoping review.

Heal Res Policy Syst. 2019;17(1):90.

doi: 10.1186/s12961-019-0490-6Lawrence L, Bishop A, Curran J.

Integrated Knowledge Translation with Public

Health Policy Makers: A Scoping Review.

Healthc Policy | Polit Santé. 2019;14(3):55–77.

doi: 10.12927/hcpol.2019.25792Uzochukwu B, Onwujekwe O, Mbachu C, Okwuosa C, et al.

The challenge of bridging the gap between researchers

and policy makers: experiences of a Health Policy

Research Group in engaging policy makers to

support evidence informed policy making in Nigeria.

Global Health. 2016;12(1):67.

doi: 10.1186/s12992-016-0209-1Dobbins M, Traynor RL, Workentine S, Yousefi-Nooraie R.

Impact of an organization-wide knowledge translation

strategy to support evidence-informed public

health decision making.

BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1412.

doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6317-5Kwok EY, Moodie ST, Cunningham BJ, Oram Cardy J.

Barriers and Facilitators to Implementation of

a Preschool Outcome Measure: An Interview Study

with Speech-Language Pathologists.

J Commun Disord. 2022;95:106166.

doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2021.106166Cassidy CE, Shin HD, Ramage E, Conway A, Mrklas K, et al.

Trainee-led research using an integrated knowledge

translation or other research partnership approaches:

a scoping review.

Heal Res Policy Syst. 2021;19(1):135.

doi: 10.1186/s12961-021-00784-0Haynes A, Rowbotham SJ, Redman S, Brennan S.

What can we learn from interventions that aim

to increase policy-makers’ capacity to use

research? A realist scoping review.

Heal Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):31.

doi: 10.1186/s12961-018-0277-1McLean RKD, Graham ID, Tetroe JM, Volmink JA.

Translating research into action: an international

study of the role of research funders.

Heal Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):44.

doi: 10.1186/s12961-018-0316-yZych MM, Berta WB, Gagliardi AR.

Initiation is recognized as a fundamental early

phase of integrated knowledge translation (IKT):

qualitative interviews with researchers and

research users in IKT partnerships.

BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):772.

doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4573-4Alvarez E, Lavis JN, Brouwers M, Schwartz L.

Developing a workbook to support the contextualisation

of global health systems guidance: a case study

identifying steps and critical factors for

success in this process at WHO.

Heal Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):19.

doi: 10.1186/s12961-018-0297-xDagne AH, Tebeje H, Mariam D.

Research utilisation in clinical practice:

the experience of nurses and midwives

working in public hospitals.

Reprod Health. 2021;18(1):62.

doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01095-x.Heinsch M.

Exploring the Potential of Interaction Models

of Research Use for Social Work.

Br J Soc Work. 2018;48(2):468–486.Boehm LM, Stolldorf DP, Jeffery AD.

Implementation Science Training and Resources for

Nurses and Nurse Scientists.

J Nurs Scholarsh. 2020;52(1):47–54.

doi: 10.1111/jnu.12510.Kingsnorth S, Orava T, Parker K, Milo-Manson G.

From knowledge translation theory to practice:

developing an evidence to care hub in a

pediatric rehabilitation setting.

Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(6):869–879.

doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1514075.Morgan S, Hanna J, Yousef GM.

Knowledge Translation in Oncology.

Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;153(1):5–13.

doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqz099.Martin D, Miller AP, Quesnel-Vallée A, Caron NR.

Canada’s universal health-care system:

Achieving its potential.

Lancet. 2018;391(10131):1718–1735.

doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30181-8College of Chiropractors of Ontario.

Electronic Public Information Package For

Council Meeting. 2024. Available from:

https://cco.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/

Public-Council-Mtg.-September-13-2024.pdf.Robinson S, Sadiq A, Wadhawan V.

Attitudes of Ontarians Toward Chiropractic Care (PN 10380)

Environics Res. 2019;(7)Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association (CLHIA)

Canadian Life and Health Insurance Facts.

2021 Edition. 2021.

http://clhia.uberflip.com/i/1409216-canadian-life-

and-health-insurance-facts-2021/0Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR)

Funding Overview. 2021.

https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/37788.htmlHarris R, Peeace D.

Private correspondence. 2021Canadian Institutes of

Heatlh Research (CIHR) Project Grant:

Spring 2021 results. 2021.

https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/52598.htmlBrown DM. Allan C. Gotlib, DC, CM:

A worthy Member of the Order of Canada.

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2016;60(1):106–122.Ontario Chiropractic Association (OCA)

OCA Aspire. 2022. https://ocaaspire.ca/Schneider MJ, Evans R, Haas M, Leach M, Hawk C, et al.

US Chiropractors' Attitudes, Skills and Use

of Evidence-based Practice: A Cross-

sectional National Survey

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2015 (May 4); 23: 16Bussières AE, Terhorst L, Leach M, Stuber K, et al.

Self-reported Attitudes, Skills and Use of

Evidence-based Practice Among Canadian

Doctors of Chiropractic: A National Survey

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2015 (Dec); 59 (4): 332–348 .Alcantara J, Leach MJ.

Chiropractic attitudes and utilization of

evidence-based practice: The use of the

EBASE questionnaire.

Explore. 2015;11(5):367–376.

doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2015.06.002.Russell I, Underwood M, Brealey S, Burton K, et al.

United Kingdom Back Pain Exercise and Manipulation (UK BEAM)

Randomised Trial: Effectiveness of Physical Treatments

for Back Pain in Primary Care

British Medical Journal 2004 (Dec 11); 329 (7479): 1377–1384Sobell LC.

Bridging the Gap Between Scientists and

Practitioners: The Challenge Before Us

– Republished Article.

Behav Ther. 2016;47(6):906–919.

doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.007Metzler MJ, Metz GA.

Translating knowledge to practice:

An occupational therapy perspective.

Aust Occup Ther J. 2010;57(6):373–379.

doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2010.00873.x.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR.

Fostering implementation of health services research

findings into practice: a consolidated framework

for advancing implementation science.

Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50.

doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50.Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, O’Connor D, Patey A, et al.

A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of

behaviour change to investigate implementation problems.

Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):77.

doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R.

The behaviour change wheel: A new method for

characterising and designing behaviour

change interventions.

Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):42.

doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42.Kalibala S, Nutley T.

Engaging Stakeholders, from Inception and Throughout

the Study, is Good Research Practice to Promote

use of Findings.

AIDS Behav. 2019;23(S2):214–219.

doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02574-w.Babatunde FO, MacDermid JC, MacIntyre N.

A therapist-focused knowledge translation intervention

for improving patient adherence in musculoskeletal

physiotherapy practice.

Arch Physiother. 2017;7(1):1.

doi: 10.1186/s40945-016-0029-xGagliardi AR, Légaré F, Brouwers MC, Webster F, Badley E.

Patient-mediated knowledge translation (PKT)

interventions for clinical encounters:

a systematic review.

Implement Sci. 2015;11:1–13.

doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0389-3Emary PC, Brown AL, Oremus M, Mbuagbaw L, Cameron DF, et al.

Association of Chiropractic Care With Receiving an Opioid

Prescription for Noncancer Spinal Pain Within a Canadian

Community Health Center: A Mixed Methods Analysis

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2022 (Aug 23); S0161-4754(22)00086-0Emary PC, Brown AL, Oremus M, Mbuagbaw L, Cameron DF, et al.

The association between chiropractic integration in

an Ontario community health centre and continued

prescription opioid use for chronic non-cancer

spinal pain: a sequential explanatory mixed methods study.

BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):1313.

doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08632-9.

Return to EVIDENCE–BASED PRACTICE

Since 12-24-2025

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |