The Ontario Chiropractic Association's Evidence-Based

Framework Advisory Council: Enhancing Patient Care

Through the Comprehensive Integration of

the Pillars of Evidence-based PracticeThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Can Chiropr Assoc 2025 (Nov); 69 (3): 224–237 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Caroline Brereton, MBA • Jessica M. Parish, BA (Hons), MA, PhD • Deborah Kopansky-Giles, BPHE, DC, FCCS, MSc

Anita Chopra, BA, DC • Bernadette Murphy, DC, PhD • Brian Gleberzon, BA, DC, MHSc, PhD

Sean Batte, BSc, DC, MSc

The Ontario Chiropractic Association.

School of Public Policy and Administration,

Carleton University,

Ottawa, Ontario.

Supporting chiropractors to deliver Evidence Based Care (EBC) is an important role that professional organizations fulfill in the practice ecosystem. This is a journey that can be accelerated when there is a shared understanding of the elements of Evidence Based Practice (EBP) and the benefits that accrue when applied comprehensively to patient care. The Ontario Chiropractic Association (OCA) undertook a significant project to advance this understanding and enhance these benefits. This paper describes the principles, processes and outputs of our work, which is a series of papers examining the EBP framework in detail. It details why this work is necessary for the chiropractic profession, how it was accomplished, and introduces the themes of each of the six other papers in the series. We aim to support chiropractors in delivering comprehensive care through the application of the evidence-based framework enabling them to practice within the full chiropractic scope of practice in compliance with applicable regulations and legislations.

Author’s note: This paper is one of seven in a series exploring contemporary perspectives on the application of the evidence-based framework in chiropractic care. The Evidence Based Chiropractic Care (EBCC) initiative aims to support chiropractors in their delivery of optimal patient-centred care. We encourage readers to review all papers in the series.

Keywords: chiropractic; evidence-based practice.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Since the birth of the Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) movement in the 1990s, there has been much debate within the chiropractic profession, and across diverse healthcare settings, as to what precisely evidence-based care ought to entail in practice. [1–7] What role do patient values and preferences play in the planning and delivery of evidence-based care plans? How are patient values and preferences best ascertained by clinicians and what happens when they conflict with best available research evidence? Is clinical expertise best understood as a form of evidence or, instead, as a lens through which research evidence is appraised and integrated with other clinically relevant information? What are the barriers to successful integration of research evidence in clinical practice and how can these be overcome?

These are important questions, and this paper introduces and describes the principles, processes and outputs of our work to answer these questions and advance a shared vision for evidence-based practice (EBP). Specifically, our objectives here were to describe the formation of the Evidence-Based Framework Advisory Council (EBFAC), the selection of an EBP model around which to structure our work, and the development of initial deliverables for promoting a shared understanding of EBP.

The Ontario Chiropractic Association’s (OCA) EBFAC was created to support chiropractors in their delivery of evidence-based, patient-centred and interprofessional care in collaboration with their patients. Beginning in January 2020 the EBFAC delved into the nuances of these debates, outlined above, and their implications for the theory and practice of evidence-based chiropractic care. Through this work, the EBFAC provided professional input surrounding optimal models of EBP for chiropractic care and engaged in a series of discussions designed to provide a foundation for a holistic understanding of EBP in the chiropractic profession. The results of these research driven conversations are presented here in a series of papers and a clinical decision tool, which the EBFAC reviewed and approved. The goal of these papers is to create a foundation upon which the OCA will build as it works to develop programming and foster partnerships to support the profession in Ontario – and elsewhere – to grow and advance through a shared understanding of evidence-based chiropractic care.

The work presented in this special edition of the JCCA explores leading practices from other professions globally and aligns with important professional advancement and thought leadership work underway elsewhere, including the World Federation of Chiropractic’s #EPIC model of care, [8] the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College’s work on core competencies, [9] and the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) work undertaken at the Canadian Chiropractic Association. [10] These initiatives are essential to raise the quality of care that all health professionals provide.

Why undertake this work?

Over the past 30 years, the Global Burden of Disease Group [11] have recognized that musculoskeletal (MSK) disorders – particularly low back and neck pain – are the leading cause of disability globally. In North America, acute and chronic MSK conditions and associated work disability have been characterized as a public health crisis. [12, 13] They are associated with poverty and suffering at the individual level and place tremendous strain on both public and private health and social services systems. [12, 13]

In addition to accounting for a substantial use of financial resources, neuromusculoskeletal (nMSK) conditions negatively impact the quality of life of people, their families, and communities. [12, 14] The impact of the social determinants of health mean that the negative impacts of ill health are felt more acutely by some than others. Socially and economically marginalized populations – such as people living in poverty, Indigenous people, racialized people, and women – experience higher instances and greater severity of disease. This necessitates the urgent advancement of effective, equitable and accessible treatment strategies to help manage those with chronic health conditions and pain as well as to mitigate the burden they place on healthcare systems. [12, 14, 15]

The chiropractic profession recognizes the importance of reducing inequity and advocating for all patients regardless of who they are, where they live or where they come from. As a low-cost, safe, and conservative approach, [16] evidence-based chiropractic care is well positioned to address these issues, many of which were both exacerbated and highlighted by the recent COVID-19 pandemic.

Our goal is to support chiropractors in providing equitable, quality care for all patients, and to be essential partners in their patients’ circle of care. This partnership is achieved through meaningful communication and collaboration with patients and their healthcare providers, through participation in interdisciplinary healthcare teams, and by referral to other healthcare professionals where appropriate. The optimization of this vision requires advancing our collective understanding of the complexity of delivering evidence-based care – which is, fundamentally, all about the patient. This paper introduces a series of six papers focused on various concepts of EBP to advance this vison.

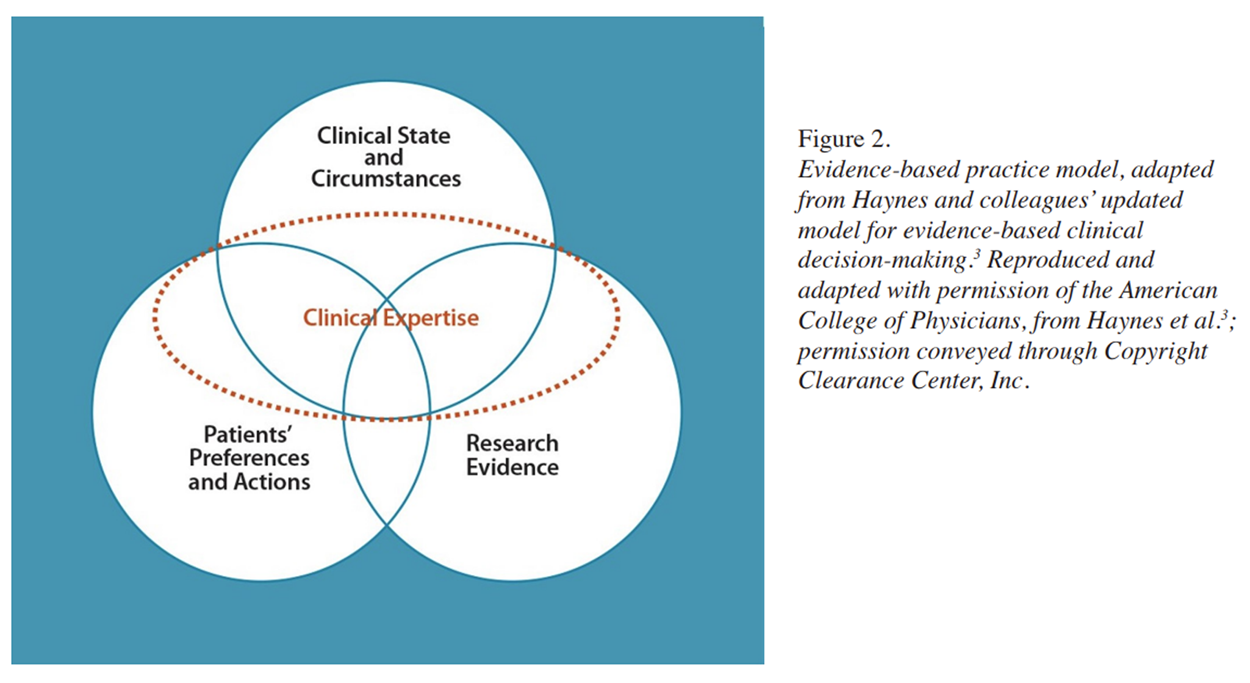

Evidence-Based Medicine and Practice

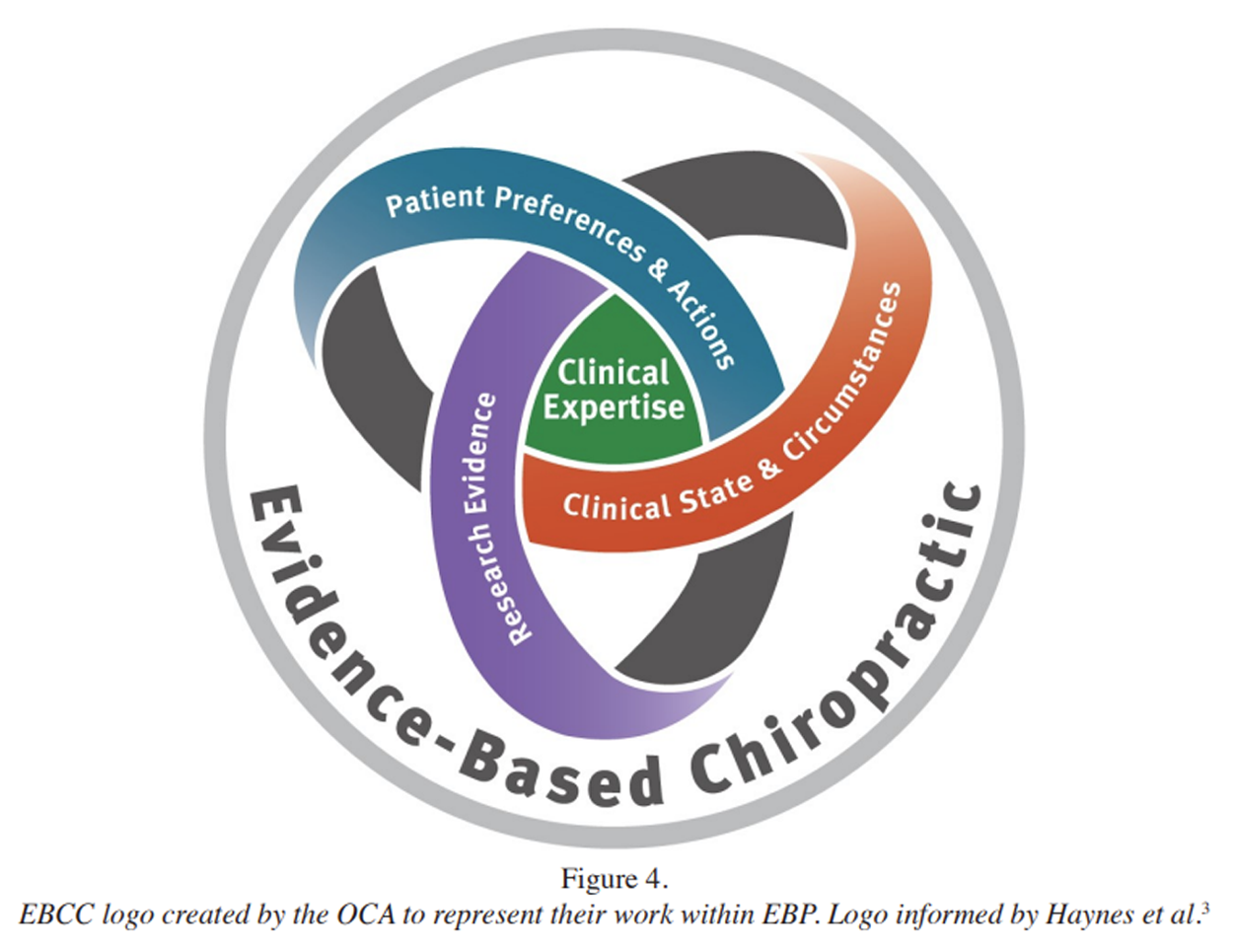

The term “Evidence Based Medicine” (EBM) was initially coined by Gordon Guyatt, David Sackett, and Brian Haynes to describe a new approach to teaching medicine. [1] It has since been taken up by a range of professions as “Evidence Based Practice” (EBP). [3, 17, 18] The first model of EBM, which came to be known as the “Sackett model” defined the three pillars as research evidence, clinical expertise and patient preferences. [2] Recognizing evolution of thought around EBM, the model was subsequently revised in 2002 by Haynes, Guyatt and Devereaux. [3] The revised “Haynes model” understands clinical expertise as the lens that integrates the pillars of patient preferences and actions, clinical state and circumstances (e.g., the patient’s health condition and the external factors impacting medical decisions), and as best available research evidence into forming a clinical decision. Considering each of these pillars within care forms the basis of EBP, it reinforces the importance of addressing social determinants of health to ensure equitable and accessible care.

Local Association’s role and contributions

It is well documented across healthcare professions that there are numerous challenges to the timely and effective integration of emerging research into practice. [19–24] Research has also demonstrated that knowledge translation efforts have tended to focus more on individual behaviour change within clinical and health services contexts and less on broader system-level change. [23] However, given the complexity of the knowledge translation ecosystem, multi-level, multi-strategy approaches are needed. [19, 23–25]

Canadian chiropractors have been found to have positive attitudes towards Evidence-Based Practice (EBP), high self-reported EBP skills and expressed significant (over 90% of respondents) interest in improving these skills. [26, 27] Notwithstanding this level of enthusiasm, research has reported that opportunities remain to improve EBP in clinical practice. Key barriers to chiropractors’ participation in EBP are: [26–28]

lack of appropriate/relevant clinical research evidence

lack of time

lack of industry support for EBP

insufficient skills to critically appraise the literature and

insufficient skills for interpreting research

These suggest that passive strategies do not necessarily result in clinical application of new knowledge and research, and underscores the need for strategies that are active, diverse, and on-going to meet the continuing education needs of the profession and advance evidence-based practice. [27]

To this end, there have been several important developments within the profession since the publication of these studies. In recent years, the Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative (CCGI) [29] and the Canadian Chiropractic Research Foundation (CCRF) [30] have made considerable progress in their respective areas of expertise in research funding and guideline development. The CCRF has invested over $1.5 million for nMSK projects and developed unique partnerships to support chiropractic-relevant research. Likewise, CCGI has created rich content and resources to support chiropractors’ increased uptake of EBP, including evidence syntheses, practice guidelines, clinician briefs, and patient handouts and videos. The establishment of EBFAC and the contributions presented here seek to build on this important work.

Established in 1929, the Ontario Chiropractic Association (OCA) has ~3,800 members, representing more than 80 per cent of Ontario’s chiropractors. The OCA’s mission is to serve its members and the public by advancing the understanding of chiropractic care and demonstrating the benefits to the broader healthcare system by reducing barriers to access chiropractic care. [31] Advancing evidence-based practice and research are integral to this work. The OCA is therefore well positioned to play a key role in strengthening the existing knowledge translation ecosystem for Ontario chiropractors. The OCA’s EBFAC is building accessible tools to support chiropractors in their delivery of evidence based, patient-centred and interprofessional care in collaboration with their patients.

Why the OCA’s EBFAC was established

The OCA’s EBFAC was established to develop a shared understanding in the Ontario context around what exactly “evidence-based practice” means for chiropractic care, how it can be advanced through the work of chiropractors and chiropractic organizations, and what factors facilitate or restrict its application. During strategic planning in 2018, senior management at the OCA met with chiropractors from across the province to understand their needs and visions for the future. During these conversations, it became clear that, in addition to the range of views on what EBP meant, there was also a gap between the research evidence being generated and a chiropractic clinician’s access, knowledge, and skillset needed to apply it into daily practice. This observation aligns with a key finding from the research on barriers and facilitators to the integration of EBP in many professions including chiropractic. [26, 27, 32–35]

The evidence-base for the safety and efficacy of spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) and other types of clinical interventions chiropractors use for low back pain is well documented in high quality research and guidelines. [16, 36] However, guidelines and other forms of high-quality research are not always applicable to the circumstances of individual patients. Moreover, in the Ontario context, there is much that falls within the chiropractic scope of practice, in addition to the management of back pain, that is still being investigated to generate a robust evidence base.

Legislation in Ontario defines the chiropractic scope of practice as:“the assessment of conditions related to the spine, nervous system and joints and the diagnosis, prevention and treatment, primarily by adjustment of:

[37]dysfunctions or disorders arising from the structures or functions of the spine and the effects of those dysfunctions or disorders on the nervous system; and

dysfunctions or disorders arising from the structures or functions of the joints.”This chiropractic scope of practice does provide for a chiropractor’s expert role in addressing the breadth of MSK needs of patients with treatment that includes not only joint manipulation or adjustment, but also behaviour modification coaching, exercise prescription, soft tissue therapy, and education to name a few. However, the legislated chiropractic scope of practice in Ontario and elsewhere does not articulate the patient-centred, biopsychosocial model of health that chiropractors use to practice in collaboration with their patients.

The OCA is both an advocacy organization and a contributor of significant funds to research foundations, such as the Canadian Chiropractic Research Foundation (CCRF), a registered charity dedicated to funding chiropractic research. The organization is well positioned to support the growth of the evidence base to drive optimal, high-quality patient-centred care across the full scope of practice. It is important that research informs practice, and that practice also informs research. The OCA can do this by cultivating stronger connections between existing clinical practice – which is frequently where the generative questions and observations that fuel new generations of research come from – and the research community, where the knowledge, skill, and resources to answer most pressing clinical questions is concentrated.

It was in response to these challenges and opportunities that the idea for the OCA EBFAC was born. EBFAC was conceived as a group of experts consisting of chiropractic clinicians, educators and researchers, including a person with lived experience, representing a breadth of professional experiences and viewpoints about EBP. The OCA sought to bring these experts together to engage in a process of shared learning and consensus development around what EBP means for the Ontario chiropractic community.

Evidence Based Framework Advisory Council

EBFAC consisted of 13 members [38] drawn from across Ontario, representing a diverse cross-section of the profession. The EBFAC also included a patient. The recruitment method used to compose EBFAC was purposeful sampling: that is, members were chosen who were considered ‘information rich’, [39] based on their career stage, recognition within the profession, education, awards, and international experience among other criteria. [38] Care was taken to ensure that gender, age and geographic diversity across the province, as well as different specializations and practice styles were taken into account when selecting members of EBFAC, ensuring broad representation from a variety of different stakeholders. The purposeful sampling method also prioritized the value of breadth and diversity of experience and practice. The OCA sought to include chiropractors who were primarily engaged in clinical practice, those primarily engaged in clinical and/or basic sciences research, as well as those primarily engaged in education/teaching. If the disconnect between clinical research and clinical practice is to be addressed, then it is important to bring these groups together.

EBFAC members were also selected for their potential to act as thought leaders and knowledge brokers within the Ontario context. This was essential to lay the foundation for future dissemination, impact, and sustainability of this work. From the outset, it was recognized that building consensus through a process of deep exploration and shared learning would just be the beginning. Future steps will be to take the lessons and implications from this work and use it to develop practical strategies and resources to support Ontario’s chiropractors in transforming their positive attitudes towards EBP into concrete, patient-centred clinical practices and outcomes.

EBFAC members were initially invited to meet for a period of 18–24 months, however that period was later extended as the scope of the work grew. During this time EBFAC met as a whole council on 12 occasions. EBFAC also formed five smaller working groups, members of which met dozens of times to develop specific outputs (e.g. separate but interconnecting articles) included in the over-arching project. Except for the first meeting, which took place over a day and a half in January 2020, all meetings were conducted virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Consensus development and shared learning

To guide the structure of the meetings and facilitate consensus development within EBFAC, we used a modified version of the Nominal Group Technique (NGT). [40–43] We combined this method with the Glasser technique [43] to extend our consensus outcomes into a series of papers which document the outcomes of our process of shared learning. Consensus on article structure (e.g., identifying chiropractic topics that require further exploration) and content (e.g., outlining key discussion points for each topic) within our group was deemed to have 100% agreement. Each of these papers were then extended into research papers to situate our views within the contemporary literature on the constituent elements of EBP. Each review then came with its own, separate methodology, which is detailed in each respective paper. It is this consensus development and shared learning process to initially develop ‘white papers’ on each of these topics that served as initial rationale for the research papers presented in this series.

The Nominal Group Technique is a method of conducting “a structured meeting that attempts to provide an orderly procedure for obtaining qualitative information from target groups who are most closely associated with a problem area”. [43] In this method a professional facilitator poses structured questions to the group, provides time for quiet reflection, and facilitates round robin discussion before moving the group to final agreement on a given issue or question. [40, 43] NGT provides participants an opportunity to have their voices heard and opinions considered by other members. It is therefore conducive to building the sense of collaboration and shared purpose needed to undertake a complex and lengthy process of developing helpful, value added outputs. In our application of this method, all meetings were led by an external facilitator with expertise in consensus development and organizational learning and development and NGT.

The structured questions were developed by OCA leadership and staff in collaboration with the facilitator and were designed to encourage EBFAC members to offer critical reflections and engage in detailed discussions of each topic. Some questions solicited open comment while others directed attention to specific issues, including research methods, strengths and weaknesses of evidence and argument, and clarity of the paper’s structure and language relative to its intended audience which, crucially, includes practicing chiropractic clinicians.

The Glasser method is an iterative process through which a small group of invited participants develop a consensus paper on an important topic. The group drafts an initial position paper and subjects it to rounds of revisions. Once the group agrees that the draft is ready to be shared, it is circulated for comment and critique among a wider group of experts chosen for their strategic importance and knowledge in the field of interest. Once the core group has received comments from external reviewers, members further revise the paper to the point of agreement. [43]

The Glasser method is specifically designed to ensure broad visibility and endorsement of the work. This method attempts to build a high degree of support for the work undertaken by, for example, having prominent groups or individuals determine the need for and value of a comprehensive statement clarifying the level of knowledge about the issue. [43]

In our application of this method, each paper was developed by a writing team. The writing team for each paper consisted of the working group members as well as a scientific writer, an OCA staff member, and an intern for research support (e.g., preliminary literature searching, and database and citation management support). OCA staff members of the writing teams took part in all meetings and meetings were recorded and transcribed for later reference by members of the writing team.

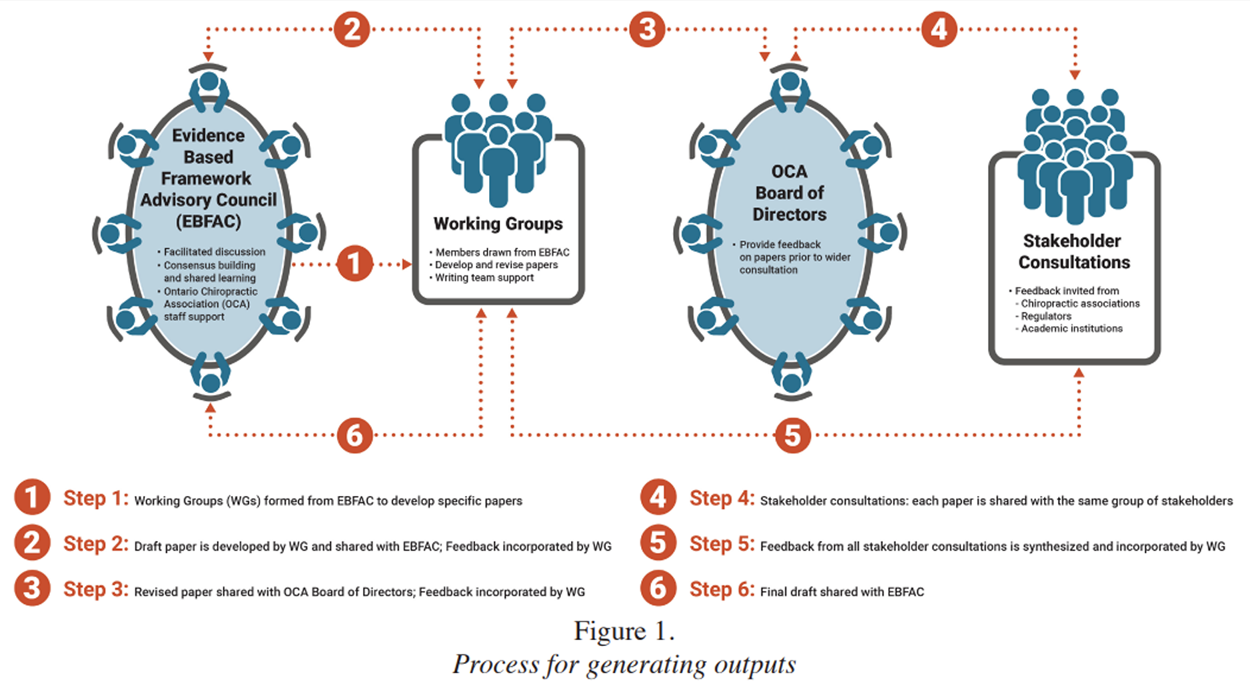

Figure 1 Because the OCA is a not-for-profit member driven organization governed by an elected Board of Directors, an intermediary step was added to the process. For each paper, after the working group agreed upon a first draft, it was then shared with the wider EBFAC and the OCA Board of Directors. After feedback from this stage was incorporated, external stakeholder groups in the chiropractic healthcare ecosystem (e.g., associations, regulators, academic institutions, and so forth) (Figure 1) were consulted and each provided additional feedback. This process involved requesting meetings with stakeholders in which drafts of papers were shared with them in advance. Stakeholders then had an opportunity to share their feedback. The feedback was referred back to the council to discuss and debate to achieve consensus on the relevance of the feedback to the paper. While each stakeholder provided their own feedback/perspectives, all were supportive of the work. Furthermore, each paper was reviewed at least once by the patient member of the EBFAC.

The methodology used by the EBFAC fostered a collaborative approach to resolve all issues on the ideological spectrum, even those that could potentially lead to professional division and impasse. This collaboration, in turn, lays the groundwork for the OCA’s long-term plan to address foundational issues around knowledge translation and the relationship between clinical research, clinical practice and patient preferences and values.

Working groups and writing teams

All working groups were composed to capture the range and breadth of experience and expertise of the EBFAC. For example, all working groups had at least one clinician and at least one researcher. At an early meeting, the facilitator administered a short thinking styles assessment to the group to help in identifying those who are “big picture” divergent thinkers and those who are more “detail oriented” convergent thinkers. This feedback was also used to inform working group development and ensure a range of intellectual approaches were represented within the working groups as well.

The methodology of shared learning

The papers in this series are both process and product. They are the result of a process that was undertaken to arrive at a shared understanding of what evidence-based practice means for chiropractors caring for patients in Ontario (and elsewhere) today. It is through the process of conceiving, planning, revising, and publishing this set of papers that a substantial depth of consensus among advisory EBFAC members was able to be achieved over a period of some two and a half years. This depth of understanding and consensus was made possible by a process of shared learning.

To speak of writing as learning means that we are attentive to the fact that there is much that comes unexpectedly, or is seen in new light, as we proceed through the processes of transforming our questions and ideas into research outputs. [44] Writing as learning means that, as a group, we committed to ourselves and each other to maintain a safe and respectful space of dialogue across our differences and to be open to integrating new realizations about material or concepts with which we are already familiar. [44] We acknowledged from the outset that such shifts in thinking and understanding would inevitably come from open-minded participation in transforming the results of round robin discussion into written sentences and paragraphs, circulating, debating and discussing drafts, and integrating external comment and critique arising through stakeholder consultation and peer 4review. [44]

As one expert on this topic writes – paraphrasing groundbreaking 20th century painter Francis Bacon – “the scholarly and scientific sentences and paragraphs in which we paint our descriptions of the world induce new understandings in us, even as we attempt to convey what we think we have to say through them”. [44, 45] In the case of collective writing, this effect is magnified. As drafts are reviewed, discussed, and critiqued authors bring the breadth of their backgrounds and experiences to the work. This in turn generates fresh insights into the manuscript through the generative force of conceptual tensions and under-explored themes as well as excitement of a particularly well-observed statement.

Selecting the Haynes model

Figure 2 One of the first priorities EBFAC needed to address was coming to consensus on the model of Evidence-Based Practice that would underpin this work. The EBFAC conducted a thorough review of landmark EBP models 4,6,7 Over the course of several discussions during meetings, the EBFAC arrived at a unanimous consensus decision to adopt the Haynes (2002) model as the preferred model of EBP for its work (Figure 2). [3] The Haynes model was chosen for the balance it strikes between comprehensiveness and clarity. Importantly, Haynes and colleagues were explicit in characterizing their model as normative: they described what EBP ought to look like, not necessarily its actual state.

EBFAC’s aim is to build and expand upon these foundational contributions for the chiropractic profession. While the papers contained in this series make extensive use of available research, they are also consciously prescriptive and future focused. With this future focused goal, the EBFAC group and our work is designed to overcome the well-documented challenges associated with real-life uptake and implementation o f EBP frameworks.46 Cautious of the poor implementation of EBP frameworks despite positive attitudes toward EBP in the chiropractic profession, [46] our selection of EBFAC promotes utilization of EBP. Specifically, our group involved multiple levels of stakeholders in the chiropractic profession which is suggested to enhance implementation both longitudinally and contextually of EBP delivery. [47]

EBFAC deliverables

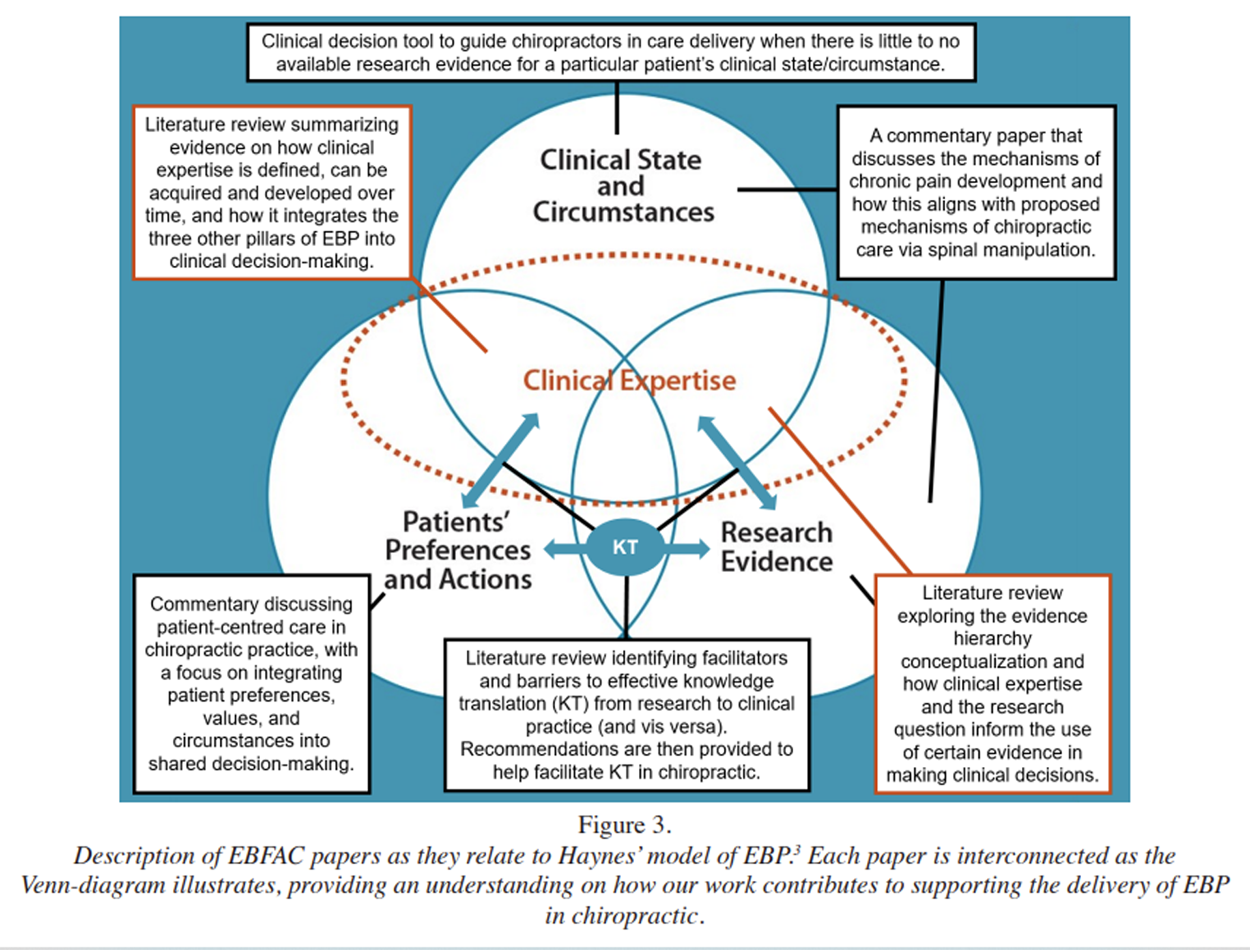

Figure 3 In selecting the topics to deliver, the EBFAC was motivated by a conviction that the advancement of evidence-based chiropractic care must begin with a detailed examination of foundational principles. For example, ‘Bridging the Knowledge-to-Action Gap in Evidence-Based Practice’ (Paper 5, described below), ties the findings of Papers 2–4 together through a practical reflection on how the stakeholders in the chiropractic ecosystem can further advance evidence-based chiropractic. Paper 6, the clinical decision tool, was developed in recognition of the fact that there are many situations where there is little or no high-quality research evidence, or where evidence is conflicting or inconclusive for the clinical state and circumstance of the patient. To visualize this and how our work deepens understanding and application of the selected Haynes’ EBP model, please see Figure 3.

The seven EBFAC papers offer comprehensive insights into each pillar of the selected Haynes EBP model to produce a shared understanding of EBP and subsequently support its delivery in the chiropractic profession. These papers collectively aim to summarize research on each pillar and how they are connected, providing a holistic view of the current state of EBP. They offer a foundation of understanding, and valuable insights and recommendations for implementing these practices. These papers are described in more detail below. Each paper directly reflects the work achieved by the EBFAC group, integrated with contemporary literature.

The Ontario Chiropractic Association’s Evidence-Based Framework Advisory Council: Enhancing patient care through the comprehensive integration of the pillars of evidence-based practice. This paper, presented above, provides an in-depth description of the rationale and process of the over-arching project.

Conceptualizing the Evidence Pyramid for Use in Clinical Practice: a narrative literature review. This paper reviews how the evidence pyramid has evolved since its conceptualization and explores contemporary iterations. It identifies the strengths and the limitations that clinicians must consider when using it to evaluate the quality of healthcare research within the context of the Haynes Model.

Person-Centred Care in Chiropractic: A Foundational but Evolving Commitment in Contemporary Practice. This commentary examines the alignment between chiropractic approaches and person-centred care, highlighting the profession’s strengths while identifying gaps in consistent implementation. It explores barriers and strategies for overcoming them at the clinician, patient, and organizational levels, and calls for a system-wide commitment to patient-centred care as a relational and evidence-informed standard of care.

Conceptualizing clinical expertise in evidence-based practice: A narrative literature review with implications for clinical decision-making. This paper reviews the recent literature on the role and definition of clinical expertise in EBP, specifically:

(i) how clinical expertise is defined and considered across disciplines,

(ii) how clinical expertise, as illustrated by the Haynes model, operates as a lens and mechanism of integration for the EBP factors of clinical state and circumstances, patients’ preferences and actions, and research evidence, and

(iii) how clinical expertise can be acquired and developed over time. Following Wieten, Paez and others, [5, 6] the EBFAC perspective increases the weight of clinical expertise relative to previous models, especially the evidence pyramid, where this is located at the bottom. [2]Enhancing evidence-based chiropractic practice: bridging the knowledge-to-action gap for the needs of community-based chiropractors. This paper reviews recent literature on Knowledge Translation (KT) in EBP. It provides an overview of the acknowledged facilitators of, and barriers to, knowledge translation through evidence integration and research utilization in chiropractic and manual therapy-based care: identifies strategies for the successful implementation of KT in clinical practice from across disciplines and jurisdictions; and draws on examples of success to propose strategies for how member-based associations can support KT and EBP for chiropractors in private community-based care settings.

When there is Little or No Research Evidence: A clinical decision tool. The purpose of this tool is to provide clinicians a logical, systematic, and evidence-based process to guide clinical decision making in situations where there is little or no high-quality research evidence, or where evidence is conflicting or inconclusive. The paper provides a detailed, systematic, and visually supported approach that is broadly applicable and provides an update on previously published similar tools (e.g. Leboeuf-Yde et al 2013 [48]). Readers will note that Parkinson’s disease (PD) was included in the set of pedagogical examples used in the tool. This was to highlight an example when there is no evidence or biological plausibility to support the use of chiropractic care and illustrate how the tool helps chiropractors in decision-making when presented with these situations.

To inform and support our use of examples which accompany the tool, an additional paper was incorporated as part of this series:

The Pathophysiologic Mechanisms of Spinal Manipulative Therapy in the Management of Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. This paper provides clinicians with an up-to-date discussion of the evidence on how central sensitization functions in the pathophysiology of chronic pain. It provides insight into bench research which helps explain why chiropractic care is effective in treating chronic pain including chronic low back pain, osteoarthritis and other nMSK pain. In addition, it discusses how SMT may be applied therapeutically to modulate the effects of central sensitization and treat associated pain. This paper highlights the relevance of fundamental neuroscience research in chiropractic care (paper 3) as well as its biological plausibility in clinical reasoning (paper 5). We included this paper in this special journal edition, both because of the crucial role that the work has played in the development of our own thinking and decision-making, and also because of the inherent interest and importance of the topic to the chiropractic profession. In the future we hope to add to this section of the series by producing robust research to further inform the “research evidence” pillar of Haynes’ EBP model.

Limitations

We recognize that the body of work we present here, while thorough, is not exhaustive. Given the nature of commentaries and narrative literature reviews, there are inherent limitations including the potential for selection bias within the articles produced throughout this work. Additionally, the clinical decision tool presented may have limitations related to its development process (e.g., potential bias from expert consensus) and the need for external validation. Our work is iterative, and it will continue to evolve as new knowledge becomes available. Future research in the form of scoping or systematic reviews is needed to further strengthen the evidence base in these areas.

While our purposeful sampling method, described above, sought to include a breadth of viewpoints and experiences, it is not necessarily a representative sample of the full breadth of the profession in Ontario. Another potential source of bias is the pre-knowledge of the members of the EBFAC. [49, 50] It is therefore possible that a different composition of EBFAC members would have generated different outputs or arrived at different conclusions.

Furthermore, while EBFAC was drawn from members of the Ontario chiropractic community with the intention to serve the local needs of OCA members, our perspective on research and leading practices was always international in its focus. As such we believe that our results and findings will be of interest to the broader chiropractic community. Indeed, our attention to local specificities, such as the legislated scope of practice, is intended to help the reader in understanding our project so that they may better compare to or apply in their own context.

Notwithstanding this, it is hoped that the reader will find that the fruits of this work make up a series of papers and practical tools to advance competencies of chiropractors across the full breadth of their scope of practice.

Conclusion

These deliverables are just the beginning. The Ontario Chiropractic Association will develop programming and partnerships that will form a cornerstone of strategic foci going forward. The aim of producing, publishing and disseminating this work is to:

Undertake a thoughtful investigation of what evidence-based practice means for the present and future of the chiropractic profession, through thorough historical and cross disciplinary examination of the core concepts of EBP [Papers 2–5]

Enhance patient-centred care by initiating and sustaining conversations on the right place of clinical expertise and patient preferences and values within evidence-based chiropractic care; and by catalyzing new partnerships and initiatives to sustain this work [papers 3 & 4]

Support the competencies of chiropractors as nMSK experts by providing theoretical knowledge as well as practical tools for the integration of evidence into clinical practice [papers 4, 5 & 6]

Develop a process for chiropractors to apply an evidence-based framework logically to patients presenting with nMSK and non-nMSK conditions, and to diagnostic and therapeutic procedures while adhering to the standards of practice, guidelines and policies of the jurisdiction in which they are practicing. [paper 6]

Support chiropractors to practice to their full scope of practice, as set out by the applicable regulatory bodies and legislation in their jurisdiction [paper 7]

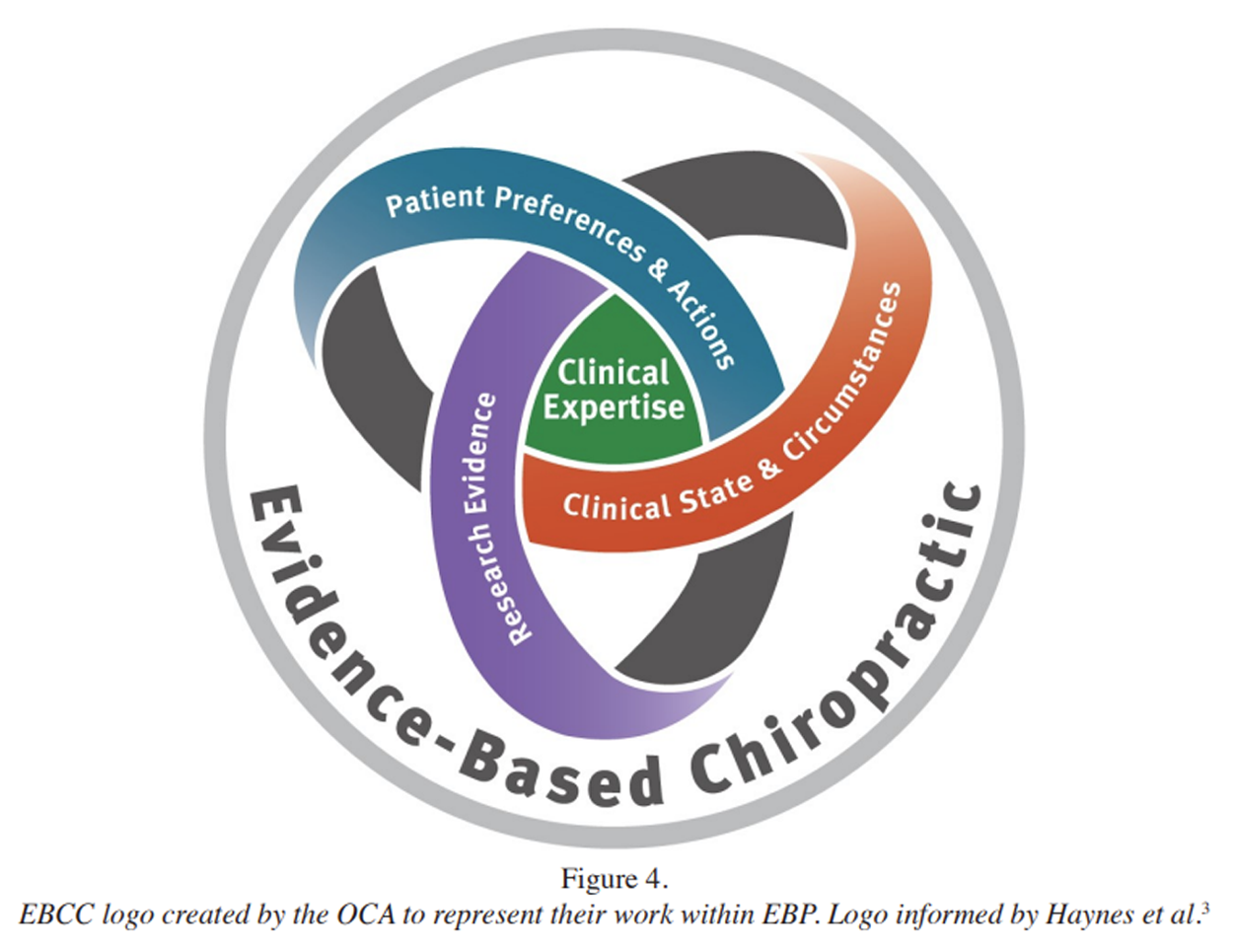

Figure 4 The body of work presented in this series seeks to clarify the distinct, but equally integral, forms of evidence that ought to inform chiropractor’s clinical decision making and to provide a rigorous and systematic path forward in situations where little or no high-quality research evidence exists. It recognizes the most important element of care: the clinician-patient relationship, and the challenges of mitigating the barriers to care patients face. Reflecting the Haynes model, the OCA created a logo to represent their EBCC work (Figure 4).

Chiropractors educate and advocate for their patients and contribute to the health of their community. Chiropractors also recognize the diverse population they serve and prioritize health equity, inclusion, and the removal of barriers to healthcare access – all of which are supported and enhanced through people-centred EBP. This work therefore aims to support all chiropractors in the science and art of chiropractic care, while respecting the diversity of practices that chiropractors bring to help patients achieve their highest quality of health and life.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the OCA. The OCA Board of Directors acknowledges the following individuals for their important roles in delivering this series of papers.

Members of the Evidence Based Framework Advisory Council: 38

Drs. Sean Batte, Ken Brough, Anita Chopra, Marco De Ciantis, Peter Emary, Brian Gleberzon, Glen Harris, Deborah Kopansky-Giles, Keshena Malik, Bernadette Murphy, Paul Nolet, Antonio Ottaviano, Rod Overton and Ms. Sheila Gregory.

Contributors to research development:

Dr. John Srbely for guidance and advice on scientific research and writing.

Dr. Carol Cancelliere for subject matter expertise in knowledge translation.

Marguerite Zimmerman for expert facilitation of the process.

Summer Sayedi, research support-select papers.

Adrienne Shinier, research and scientific writing-select papers.

Jessica Parish, writing contributions, project management and thought leadership.

Jonathan Murray, writing contributions, project management and content expertise in publication process.

Deborah Gibson, Nancy Gale, Ben Xafflorey, project coordination

Sasha Babakhanova, Domenic Mastropietro, Sandra DiValentin and Lara Neumann, graphic design.

Conflicts of Interest:

This research was funded by the OCA. The lead authors received a per diem for the team meetings they attended as part of the project. The authors declare no other conflicts of interest, including no disclaimers, competing interests, or other sources of support or funding to report in the preparation of this manuscript.

References:

Guyatt GH, Cairns JA, Churchill DN, Cook DJ, et al.

Evidence-based medicine. A new approach to teaching

the practice of medicine.

JAMA. 1992;268(17):2420–5.

doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03490170092032.Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Gray JAM, Haynes RB.

Evidence-Based Medicine:

What It Is and What It Isn't

British Medical Journal 1996 (Jan 13); 312 (7023): 71–72Haynes RB, Devereaux PJ, Guyatt GH.

Clinical expertise in the era of evidence-based medicine

and patient choice.

ACP J Club. 2002;136(2):A11–4Miller PJ, Jones-Harris AR.

The Evidence-Based Hierarchy: Is It Time For Change?

A Suggested Alternative.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28(6):453–7.

doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.06.010Wieten S.

Expertise in evidence-based medicine:

A tale of three models.

Philos Ethics, Humanit Med. 2018;13:1–7.

doi: 10.1186/s13010-018-0055-2Paez A.

The “architect analogy” of evidence-based practice:

Reconsidering the role of clinical expertise and

clinician experience in evidence-based health care.

Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine. 2018;11:219–26.

doi: 10.1111/jebm.12321Murad MH, Asi N, Alsawas M, Alahdab F.

New evidence pyramid.

Evid Based Med. 2016;21(4):125–7.

doi: 10.1136/ebmed-2016-110401World Federation of Chiropractic.

Quarterly World Report. 2019Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College (CMCC)

Doctor of Chiropractic Program Graduate Competencies. 2021Canadian Chiropractic Association (CCA)

Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. Jun 18, 2020. Available from:

https://chiropractic.ca/diversity-equity-and-inclusion/Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries

and territories 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for

the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.

Lancet. 2020 Oct;396(10258):1204–22.

doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9Chronic Pain in Canada:

Laying a Foundation for Action

A Report By The Canadian Pain Task Force, June 2019Toms Barker L, Shaw W, Gatchel R, Christian J.

Improving pain management and support for workers with

musculoskeletal disorders: Policies to prevent

work disability and job loss volume 1:

Policy Action Paper. 2017:3Schopflocher D, Taenzer P, Jovey R.

The Prevalence of Chronic Pain in Canada.

Pain Res Manag. 2011;16:876306.

doi: 10.1155/2011/876306Srbely JZ, Vernon H, Lee D, Polgar M.

Immediate Effects of Spinal Manipulative Therapy on

Regional Antinociceptive Effects in Myofascial

Tissues in Healthy Young Adults

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2013 (Jul); 36 (6): 333–341Hawk C, Whalen W, Farabaugh RJ, Daniels CJ, et al.

Best Practices for Chiropractic Management of Patients

with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain:

A Clinical Practice Guideline

J Altern Complement Med 2020 (Oct); 26 (10): 884–901Engels C, Boutin E, Boussely F, Bourgeon-Ghittori I, et al.

Use of Evidence-Based Practice Among Healthcare

Professionals After the Implementation of a

New Competency-Based Curriculum.

Worldviews Evidence-Based Nurs. 2020;17(6):427–36.

doi: 10.1111/wvn.12474.Mackey A, Bassendowski S.

The history of evidence-based practice in nursing

education and practice.

J Prof Nurs. 2017;33(1):51–5.

doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2016.05.009.Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) CI.

About us: Knowledge translation at CIHR. 2016Field B, Booth A, Ilott I, Gerrish K.

Using the Knowledge to Action Framework in practice:

a citation analysis and systematic review.

Implementation science : IS. 2014;9:172.

doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0172-2.Larocca R, Yost J, Dobbins M, Ciliska D, Butt M.

The effectiveness of knowledge translation strategies

used in public health : a systematic review.

BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1.

doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-751Luciano M, Aloia T, Brett J.

4 ways to make evidence-based practice the norm in health care.

Harvard Business Review. 2019. Available from:

https://www.physicianleaders.org/articles/

evidence-based-practicesKawchuk G, Newton G, Srbely J, Passmore S, et al.

Knowledge Transfer Within the Canadian Chiropractic

Community Part 2: Narrowing the Evidence-Practice Gap

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2014 (Sep); 58 (3): 206–214Kawchuk G, Bruno P, Busse J, Bussières A, Erwin M, et al.

Knowledge Transfer Within the Canadian Chiropractic

Community Part 1: Understanding Evidence-Practice Gaps

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2013 (Jun); 57 (2): 111–115Armstrong R, Waters E, Dobbins M, Anderson L, Moore L, et al.

Knowledge translation strategies to improve the use

of evidence in public health decision making in

local government: Intervention design

and implementation plan.

Implement Sci. 2013;8(1)

doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-121Bussières AE, Terhorst L, Leach M, Stuber K, Evans R, et al.

Self-reported Attitudes, Skills and Use of Evidence-based

Practice Among Canadian Doctors of Chiropractic:

A National Survey

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2015 (Dec); 59 (4): 332–348Schneider MJ, Evans R, Haas M, Leach M, Hawk C, Long C, et al.

US Chiropractors' Attitudes, Skills and Use of

Evidence-based Practice: A Cross-sectional

National Survey

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2015 (May 4); 23: 16Walker BF, Stomski NJ, Hebert JJ, French SD.

Evidence-based practice in chiropractic practice:

A survey of chiropractors’ knowledge, skills,

use of research literature and barriers to

the use of research evidence.

Complement Ther Med. 2014;22(2):286–95.

doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2014.02.007.Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative.

Available from: https://www.ccgi-research.com/Canadian Chiropractic Research Foundation. Available from:

https://canadianchiropracticresearchfoundation.ca/Ontario Chiropractic Association.

Available from: https://chiropractic.on.ca/Ciliska D.

Introduction to Evidence-Informed Decision Making

How do I use this learning module? Scenario:

Other format PDF version (780 KB) Available from:

https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/45245.html#b5.Bussières AE, Zoubi F, Al Stuber K, French SD, Boruff J, et al.

Evidence-based Practice, Research Utilization,

and Knowledge Translation in Chiropractic:

A Scoping Review

BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016 (Jul 13); 16 (1): 216Ammendolia C, Bombardier C, Hogg-Johnson S, Glazier R.

Views on radiography use for patients with acute low

back pain among chiropractors in an Ontario community.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2002;25(8):511–20.

doi: 10.1067/mmt.2002.127075De Carvalho D, Bussières A, French SD, Wade D, et al.

Knowledge of and adherence to radiographic guidelines

for low back pain: a survey of chiropractors

in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada.

Chiropr Man Therap. 2021 Jan;29(1):4.

doi: 10.1186/s12998-020-00361-2NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence)

Chronic Pain (Primary and Secondary) in Over 16s:

Assessment of All Chronic Pain and Management

of Chronic Primary Pain

NICE guideline Published: April 7, 2021 (NG193)College of Chiropractors of Ontario

Scope of Practice and Authorized Acts. 2021. Available from:

https://cco.on.ca/members-of-the-public/scope-of-practice-and-authorized-acts/Ontario Chiropractic Association (OCA)

OCA Evidence-based Framework Advisory Council. Available from:

https://chiropractic.on.ca/about-oca/who-we-are/oca-advisory-councils/Baker S, Edwards R, Doidge M.

How many qualitative interviews is enough?:

Expert voices and early career reflections on

sampling and cases in qualitative research. 2012McMillan SS, King M, Tully MP.

How to use the nominal group and Delphi techniques.

Int J Clin Pharm. 2016 Jun;38(3):655–62.

doi: 10.1007/s11096-016-0257-xMcMillan S, Kelly F, Sav A, Kendall E, King M, Whitty J, et al.

Using the Nominal Group Technique:

How to analyse across multiple groups.

Heal Serv Outcomes Res Methodol. 2014;14:92–108.Jones J, Hunter D.

Consensus methods for medical and health services research.

BMJ. 1995 Aug;311(7001):376–80.

doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376Fink A, Kosecoff J, Chassin M, Brook RH.

Consensus methods: characteristics and guidelines for use.

Am J Public Health. 1984 Sep;74(9):979–83.

doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.9.979Magee P.

Writing as Discovery: Investigating a Hidden Component

of Scholarly Method.

Interdiscip Lit Stud. 2019;21(3):297–319Sylvester D, Bacon F.

The brutality of fact: Interviews with Francis Bacon.

3rd enlarged ed. London: Thames & Hudson; 1987Leach MJ, Palmgren PJ, Thomson OP, Fryer G, et al.

Skills, attitudes and uptake of evidence-based practice:

a cross-sectional study of chiropractors in the

Swedish Chiropractic Association.

Chiropr Man Therap. 2021;29:1–12.

doi: 10.1186/s12998-020-00359-w.Moullin JC, Dickson KS, Stadnick NA, Albers B, et al.

Ten recommendations for using implementation frameworks

in research and practice.

Implement Sci Commun. 2020;1:1–12.

doi: 10.1186/s43058-020-00023-7.Leboeuf-Yde C, Lanlo O, Walker BF.

How to Proceed When Evidence-based Practice

Is Required But Very Little Evidence Available?

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2013 (Jul 10); 21 (1): 24Onwuegbuzie AJ, Leech NL.

A Call for Qualitative Power Analyses.

Quality & quantity. 2007:105–21Bengtsson M.

How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis.

NursingPlus Open. 2016;2:8–14.

Return to EVIDENCE–BASED PRACTICE

Since 1-05-2026

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |