Interdisciplinary Practice Models for Older Adults

With Back Pain: A Qualitative EvaluationThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Gerontologist. 2018 (Mar 19); 58 (2): 376–387 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Stacie A. Salsbury, PhD, RN, Christine M. Goertz, DC, PhD, Robert D. Vining, DC,

Maria A. Hondras, DC, MPH, PhD, Andrew A. Andresen, MD, Cynthia R. Long, PhD,

Kevin J. Lyons, PhD, Lisa Z. Killinger, DC and Robert B. Wallace, MD, MS

Palmer Center for Chiropractic Research,

Palmer College of Chiropractic,

Davenport, Iowa.PURPOSE: Older adults seek health care for low back pain from multiple providers who may not coordinate their treatments. This study evaluated the perceived feasibility of a patient-centered practice model for back pain, including facilitators for interprofessional collaboration between family medicine physicians and doctors of chiropractic.

DESIGN AND METHODS: This qualitative evaluation was a component of a randomized controlled trial of 3 interdisciplinary models for back pain management: usual medical care; concurrent medical and chiropractic care; and collaborative medical and chiropractic care with interprofessional education, clinical record exchange, and team-based case management. Data collection included clinician interviews, chart abstractions, and fieldnotes analyzed with qualitative content analysis. An organizational-level framework for dissemination of health care interventions identified norms/attitudes, organizational structures and processes, resources, networks-linkages, and change agents that supported model implementation.

RESULTS: Clinicians interviewed included 13 family medicine residents and 6 chiropractors. Clinicians were receptive to interprofessional education, noting the experience introduced them to new colleagues and the treatment approaches of the cooperating profession. Clinicians exchanged high volumes of clinical records, but found the logistics cumbersome. Team-based case management enhanced information flow, social support, and interaction between individual patients and the collaborating providers. Older patients were viewed positively as change agents for interprofessional collaboration between these provider groups.

IMPLICATIONS: Family medicine residents and doctors of chiropractic viewed collaborative care as a useful practice model for older adults with back pain. Health care organizations adopting medical and chiropractic collaboration can tailor this general model to their specific setting to support implementation.

KEYWORDS: Care coordination; Evaluation; Integrative medicine; Pain management; Patient-centered care; Teams/interdisciplinary/multidisciplinary

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Background

Low back pain (LBP) is a common and costly musculoskeletal complaint among older adults (Patel, Guralnik, Dansie, & Turk, 2013; Weiner, Kim, Bonino, & Wang, 2006). Not only is back pain a nagging reminder of the aging process (Makris et al., 2015), older adults may be disabled by LBP, experiencing restricted physical function, impaired activities of daily living, increased medication use, and poor quality of life (Docking et al., 2011; Gore, Sadosky, Stacey, Tai, & Leslie, 2012; Makris, Fraenkel, Han, Leo-Summers, & Gill, 2011; Weiner, Sakamoto, Perera, & Breuer, 2006). Indeed, some researchers identify LBP and other musculoskeletal complaints as significant threats to healthy aging worldwide (Briggs et al., 2016).

Older patients may seek LBP treatment from multiple health care professionals, at times concurrently, and with little care coordination among clinicians (Lyons et al., 2013; Weigel, Hockenberry, Bentler, Kaskie, & Wolinsky, 2012). Effective treatment for back pain can be elusive as “what works” varies between patients and over episodes (Borkan, Reis, Hermoni, & Biderman, 1995; Parsons et al., 2012). However, patients with back pain often prefer to use conservative, non-pharmacological therapies over medication or surgery (Löckenhoff et al., 2013; McIntosh & Shaw, 2003; Ness, Cirillo, Weir, Nisly, & Wallace, 2005; Sherman et al., 2004).

One innovative, conservative practice model for older adults with LBP is collaborative care pairing medical doctors (MDs) and doctors of chiropractic (DCs) (Goertz et al., 2013; Lyons et al., 2013). Collaborative care for patients with complex health conditions can improve patient outcomes and satisfaction (Karlin & Karel, 2014; Scharlach, Graham, & Berridge, 2015; Tracy, Bell, Nickell, Charles, & Upshur, 2013). And yet, implementation of such interdisciplinary models is challenging. Providers often demonstrate limited knowledge of LBP diagnoses and treatment (Buchbinder, Staples, & Jolley, 2009; Cayea, Perera, & Weiner, 2006). Hundreds of treatments for LBP exist (Haldeman & Dagenais, 2008), with guidelines endorsing self-care, medication, physical therapy, exercise, spinal manipulation, and other treatments (Chou et al., 2007). Providers may not understand how to select or integrate musculoskeletal treatments from other clinicians with the services they offer (Frenkel & Borkan, 2003; Penney et al., 2016).

Recent studies of nationally representative samples of older adults demonstrate that chiropractic care has a protective effect against declines in activities of daily living and self-rated health (Weigel, Hockenberry, Bentler, & Wolinsky, 2014; Weigel, Hockenberry, & Wolinsky, 2014), comparable outcomes for functional health with medical care (Weigel, Hockenberry, Bentler, & Wolinsky, 2013), high satisfaction with care and health information (Weigel, Hockenberry, & Wolinsky, 2014), and positive safety profiles (Whedon, Mackenzie, Phillips, & Lurie, 2015). However, few medical doctors and chiropractors work in the same facility (Christensen, Hyland, Goertz, & Kollasch, 2015) and most report infrequent referrals with minimal exchange of clinical information (Greene, Smith, Haas, & Allareddy, 2007; Mainous, Gill, Zoller, & Wolman, 2000).

The purpose of this qualitative study was to evaluate multidisciplinary practice for older adults with back pain by physicians training in a family medicine residency program and licensed chiropractors from the perspectives of these provider groups. In this paper, we highlight the essential components of a collaborative care model, describe the context for establishing this interprofessional practice, and discuss the implications of this model for implementation in real-world clinical settings.

Collaborative Care Model

Figure 1

Table 1 The Collaborative Care for Older Adults with Back Pain (COCOA) model (Goertz et al., 2013) was based upon a provider-level framework for integrative medicine that includes team functions (attitudes/knowledge), referral, and clinical practice (Hsiao et al., 2006). We designed a collaborative care model with three essential components to enhance interdisciplinary communication between providers: interprofessional education, clinical record exchange, and team-based case management (Figure 1).

Interprofessional education was offered by an interdisciplinary committee to supervised family medicine residents (MDs or doctors of osteopathy [DO]) and licensed DCs. Clinicians completed four, hour-long, lunchtime workshops on professional scopes of practice, LBP management in older adults, and interdisciplinary collaboration (Table 1) and half-day job shadowing experiences at the cooperating clinic (Riva et al., 2010). Five additional trainings reinforced procedures, prevented intervention drift, and strengthened collaborative processes.

Clinical record exchanges enhanced interdisciplinary communication for clinicians working with different health care facilities and record systems (Bailey et al., 2013). A study-designed, secure, websystem using a Microsoft SQL Server (Redmond, WA) facilitated record exchanges of baseline evaluations (health history, medications, examinations, and imaging), treatment summaries, and status changes. Clinicians accessed records through the websystem with a unique log-in and password and received automated e-mails on record updates.

Team-based case management supported integrative practice. Clinicians evaluated the participant, offered recommendations, and completed telephone consultations with the collaborating doctor to discuss patient history, diagnoses, and treatment goals; treatment approaches; and status changes. The clinicians supported this shared treatment plan and treatment goals in subsequent interactions with the patient (Parsons et al., 2012).

Methods

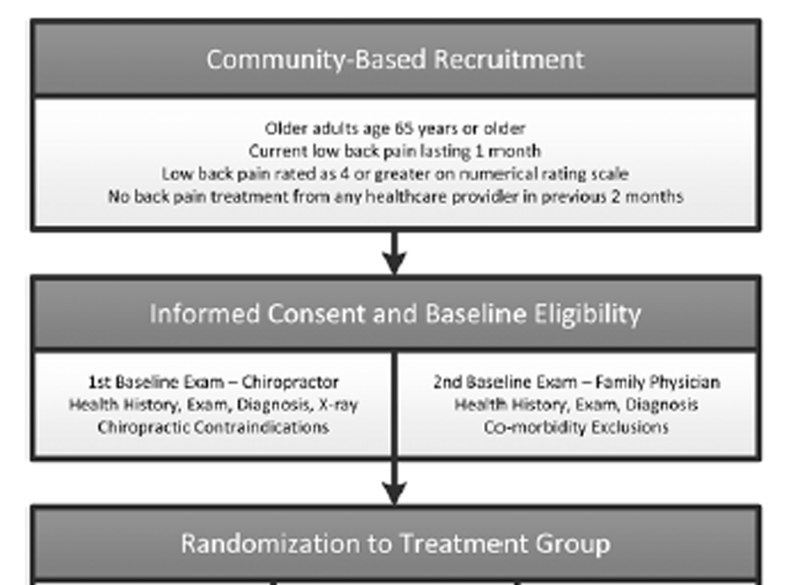

Figure 2 This evaluation was a component of a pragmatic, pilot randomized controlled trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01312233) that compared three professional models for back pain treatment (Figure 2). Our aims were to evaluate the perceived feasibility of collaborative practice by medical doctors and chiropractors, describe the context of diffusion for this intervention, and identify model facilitators for real-world implementation. Our research approach included qualitative interviews with providers, clinical record abstraction, and fieldnotes. The Institutional Review Boards of Palmer College of Chiropractic and Genesis Health System approved the study. Written consent was obtained from participants. We published the trial protocol (Goertz et al., 2013); patient outcomes will be presented elsewhere.

Setting and Participants

The settings were an unaffiliated family medicine residency and a chiropractic research center located in one community. Medical residents volunteered as providers for the trial; from these, residency faculty selected five residents from various years in the program to serve as collaborative physicians. These residents shared an office that allowed them to engage in team-based case management without exposing residents assigned to patients in other groups to this intervention. Nineteen other residents provided back pain treatments without receiving the interprofessional education. Four licensed chiropractors treated participants in both chiropractic groups, with designated patients receiving the collaborative care model. Five research fellows also received the interprofessional education, but delivered no chiropractic care. Clinicians were not the usual primary care provider or chiropractor of most participants, and therefore only treated patients for LBP. No clinician received financial incentives to participate, although all received light lunches during the noontime training sessions.

Patient participants included adults aged 65 years or older with a current LBP episode lasting at least 1 month and rated as ≥4 on a 0–10 pain numerical rating scale (NRS) at baseline. Patients were recruited from invitational letters to residency patients in the target population and from the community by direct mailers to households with an identified member aged 65 years or older within a 35-mile radius of the research center and through local media. Patients ineligible for the trial if they received LBP treatment from any provider in the previous 2 months. Enrolled patients had a median age of 72 (6.2) years, with 61% male and 94% white. Most (84%) reported LBP duration of ≥1 year, with baseline mean LBP rated as 5.8 on the NRS (Khorsan, Coulter, Hawk, & Choate, 2008) and mean score of 7.5 on the 24-item Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (Roland & Morris, 1983).

Interventions

Participants were randomized to one of three interventions (Figure 2):usual medical care (Med Care);

concurrent medical and chiropractic care (Dual Care); or

collaborative medical and chiropractic care (Shared Care).All participants received up to 12 weeks of individualized, guideline-based, usual medical care (Chou et al., 2007). Participants allocated to chiropractic also received up to 12 weeks of individualized chiropractic care consistent with best practices (Hawk, Schneider, Dougherty, Gleberzon, & Killinger, 2010). Shared Care participants received care guided by the collaborative model. Evaluations and chiropractic services were provided without cost; medical visits and therapies (physical therapy, medications) were billed to the patient or insurance. Treatment frequency was determined by the recommending provider.

Data Collection

Data were collected from qualitative interviews, clinical record audits, and fieldnotes of the educational sessions and model implementation challenges. The first author compiled all fieldnotes and conducted voluntary interviews with 19 clinicians, including 13/24 (54%) medical or osteopathic doctors and 6/9 (67%) chiropractors after trial participation. A structured interview asked clinicians their perceptions of the feasibility of model components for clinical practice settings. A service completed verbatim transcriptions from digital audio-recordings.

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics for patient demographics and record exchanges were calculated using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Qualitative data were managed with NVivo-9 software (QSR International, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia). The first author, a qualitative researcher who served as project manager of the trial, coded the transcripts for key themes underlying model feasibility using content analysis techniques (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Two co-investigators (M. A. Hondras and R. D. Vining), DCs with added expertise in clinical research and/or qualitative methods, confirmed the coding results. Data interpretation reflected the domains of the collaborative model, organized with contextual factors from an implementation framework for health care interventions (Mendel, Meredith, Schoenbaum, Sherbourne, & Wells, 2008). This implementation framework specifies factors that affect stakeholders’ willingness and ability to implement and sustain new health care interventions (including norms/attitudes, organizational structures/processes, and resources) as well as influences and information sources for disseminating such innovations (networks/linkages and media/change agents) (Mendel et al., 2008). An online Supplementary Material presents contextual factor domains, themes and representative quotes identified by provider treatment group, profession, and interview number. Quotes are included from providers who received the interprofessional training and practiced under the collaborative model, as well as those who did not, offering the reader a range of viewpoints about the barriers and facilitators of interdisciplinary care for older adults with back pain.

Results

Changing Provider Attitudes and Knowledge Through Interprofessional Education The medical residents and chiropractors who participated in the interprofessional education program reported changes in their attitudes and knowledge of the collaborating discipline, and in their perceptions of caring for older adults who have back pain (Supplementary Material—Norms and attitudes). As one medical doctor stated:I really liked the interprofessional education sessions and getting to do some of the shadowing and talking with the chiropractic folks. I learned a lot about where they were coming from and we had good discussions about medical and chiropractic care and different kinds of chiropractic treatment that I hadn’t had before.

(Shared Care MD-IN01)Several physicians noted these sessions were their introduction to chiropractic:

All that’s fascinating to me, especially when I can hear clinical outcomes and how that benefited their patients. That’s good because in medical school, they typically do not teach what a chiropractor does. Certainly in our medical journals we never have any overview of what a chiropractor does.

(Shared Care DO-IN03)Chiropractors noted these programs were among their first opportunities to observe medical doctors as collaborating professionals:

It helped to open up doors a little bit…This experience allowed…meeting somebody who’s doing this in the field on a professional level and not just of the patient, so that was enjoyable.

(Chiropractic research fellow, IN-19)Shared Care clinicians participated in up to nine educational sessions and all job shadowed for 3–5 hr. Topics covered during the lunchtime workshops (Table 1) were often mentioned as areas where provider attitudes and knowledge had changed, including professional scopes of practice, patient motivations and preferences for back pain management, and communication strategies for working with older adults. Treatment safety concerns for older people with back pain largely centered on medications, mobility issues, and comorbidities, particularly after the medical doctors had learned more about spinal manipulation:

With safety, I was worried about my patients taking their medications the way they should. Big combinations of medications and the wrong doses could potentially hurt someone…I wouldn’t say that I ever worry about chiropractic care causing a problem.

(Med/Dual Care DO-IN10)The chiropractors noted that delivery of chiropractic care to older adults sometimes required treatment modification to optimize its safety:

You have to do technique modification, and you need to take into account how much spinal and soft tissue degeneration there is and their other comorbid conditions that might impact their low back pain.

(Dual/Shared Care DC-IN15)Fieldnotes and provider interviews noted attendance discrepancies between provider groups. The institutional mission of the research center allowed the chiropractors to attend all educational sessions, whereas the patient care demands of the residency led most medical doctors to omit single training sessions or shorten attendance times:

On a logistical basis, getting out of clinic and rotations either in time to get to [sessions] or the times when our schedules ended up being blocked off and we had clinic patients starting before those ended, that was stressful… I always wish I could have stayed… arrange the scheduling a little better between the clinics.

(Shared CareMD-IN01)Recommendations for improving the interprofessional education included shorter, more frequent sessions; hands-on workshops for complex patients; and more information about the effectiveness and safety of LBP treatments for older adults.

One clinician summarized:I don’t know what kind of common forums we can participate in, but more interaction would bridge that gap, because it seemed to work well. We’re taking care of the same community, same patients. It’s just a matter of more interaction from the practitioners.

(Shared Care MD-IN09)

Organizational Structures and Processes to Support Collaboration

Organizational structures and processes are necessary infrastructures to support collaboration. Core health care technologies (Mendel et al., 2008), such as medical knowledge, clinical routines, and treatment protocols, were commonly mentioned in provider interviews as organizational features that served as barriers or facilitators of interdisciplinary communication and practice (Supplementary Material— Organizational structures and processes). Disciplinary jargon and clinical record content were areas where providers negotiated common ground:Content is probably okay…cut communication down to a one-page treatment summary. I don’t have time to read…I just want the pertinent.

(Shared Care DO-IN03)

We adapted a little bit…met in the middle…keeping it simple, one page, bare bones, need to know, rule out red flags and then one or two additional things that are very telling that may have an impact on management

(Chiropractic research fellow, IN-17)Clinicians also gained knowledge about the treatment protocols of their collaborators:

It made me more familiar with techniques and strategies and, you know, we all had the same common goal so it was reassuring more than anything.

(Shared Care MD-IN09)Chiropractors reported a better understanding of the challenges family physicians have managing older adults who have multiple comorbidities and medication use in back pain:

[The pharmacist’s] topics on the drug stuff…it was a nice gesture to see…people who work in that realm of healthcare also recognize that a lot of what they do has a relatively limited evidence-base to draw upon.

(Dual/Shared Care DC-IN05)The clinical record exchange was a challenging organizational process to implement. Overall, the clinics shared 968 records, with most exchanged during the baseline evaluation to support eligibility decisions. During active care, the number of record exchanges differed modestly between clinics. The medical clinic uploaded 110 records, including 103 treatment and 7 phone call summaries and no status change reports. The chiropractic clinic uploaded 150 records, including 86 treatment and 44 phone call summaries. Chiropractors uploaded 20 status reports indicating a participant had experienced a deterioration in health. Fieldnotes documented several logistical challenges, including multiple log-in screens and slow file uploads that required a research nurse to format, upload, and print records for medical providers. Chiropractors scanned and uploaded records, a process taking 15–30 min. One medical doctor called the record exchange process:

Impractical…the time commitment, the cumbersome nature of the electronic forms…it could work in a traditional practice, not a residency program.

(Shared Care MD-IN06)A chiropractor concurred:

Not as feasible simply because of the paperwork…along the lines of 20 pages scanned, uploaded, categorized into a secure network that is not as efficient as a commercial electronic medical records program would be.

(Chiropractic research fellow, IN-17)

Linking Providers and Patients for Better Back Health

Team-based case management served as a critical connection for information flow, social support, and interaction between patients and collaborating providers (Supplementary Material—Networks and linkages). One exemplar of case management is from an osteopathic physician and a chiropractor who commented on their shared treatment with a mutual patient who had a personal goal to stop smoking, a known risk factor for back pain:I was surprised at how effectively we worked together on one patient for smoking cessation. Part of my challenge is, I don’t see the patients as often as a chiropractic doctor would. Even though we set goals and the patient gets excited to achieve their goals, that extra reinforcement when you see them more often really does help the patient in a way I’m not able to. I was glad to see that. I was able to reinforce your suggestions and you were able to reinforce mine and ultimately the patient did benefit; although this particular one did not quit entirely, cutting down helps.

(Shared Care DO-IN03)

There was one case that comes to mind…our participant was involved in smoking cessation and the medical physician and I worked together on that with different approaches, so I think we enhanced each other.

(Dual/Shared Care DC-IN16)In contrast, clinicians who had not participated in interprofessional education reported they would likely not refer older patients for spinal manipulation because they had not developed a working relationship with a chiropractor. Another practice challenge was that the providers worked in different settings:

Normally, people that are working together are in the same building, and even in the same wing…trying to get each other on the phone has been impossible.

(Dual/Shared Care DC-IN05)And yet, the telephone consultations did offer clinicians a positive space to talk about their patient’s preferences and treatment goals:

Whenever we got to brainstorm about a particular participant’s condition, especially some of the comorbid conditions, I thought that was good because I saw these people more often and could gauge whether they were getting better or worse…and pass on that information… having access to people who can assess non-musculoskeletal problems was good, especially with this group that had so many comorbid conditions.

(Dual/SharedCare DC-IN15)Finally, the patients themselves served as the best advocates to these doctors who were just learning the possibilities of interprofessional collaboration:

The most prominent request was for a multi-disciplinary approach. [Patients] wanted both practitioners to be working at the same time, they didn’t want just one or the other. They felt the combination had an added benefit to them.

(Shared Care MD-IN09)

Most were very happy to have chiropractic care. I know a lot of them didn’t think they would get much help from the medical people. Some were given things like gabapentin or anti-inflammatories that really helped them a lot. They were glad for the collaborative care, as I was. You know, I didn’t care who did what to make them feel better. They’re patients. You just want them to feel better.

(Dual/Shared Care DC-IN15)Table 2 offers some recommendations based on the provider interviews (see Supplementary Material) for clinicians and health care organizations considering implementing collaborative practice between medical doctors and chiropractors for older adults with back pain.

Table 2. Recommendations From Provider Interviews for

Implementing Collaborative Care for Older Adults With Back Pain

Table 2A.

Table 2B.

Discussion

This qualitative study evaluated the perceived feasibility of interprofessional practice for the management of LBP that includes collaboration between family medicine physicians and doctors of chiropractic, the health professionals who most often treat older adults with this condition (Weigel et al., 2012). This collaborative care model (COCOA) included three essential components for enhancing interdisciplinary communication and practice: interprofessional education, clinical record exchanges, and team-based case management (Goertz et al., 2013). Health care innovations, such as interdisciplinary practice, require stakeholders to adopt new attitudes and knowledge and organizations to build and maintain networks between entities (Hsiao et al., 2006; Mendel et al., 2008). Interprofessional education provided a forum where medical doctors and chiropractors learned about each providers’ treatment protocols, discovered how to work together, and forged a shared commitment to patient-centered care for older patients. Clinicians were satisfied with the interprofessional education, with many listing the opportunity to know the partnering providers on a personal basis as a favorite feature of the model. Alternative educational formats, such as preclinical training, webinars, and continuing education offering credit for both professions, also might be offered (Bednarz & Lisi, 2014; Wong et al., 2014). Targeted e-learning programs similarly may improve clinicians’ skills managing back pain in older adults (Weiner et al., 2014).

Organizational structures and processes, such as health information systems, are vital supports of interprofessional collaboration (Mendel et al., 2008). These providers successfully shared over 900 clinical records, a vast improvement over previous research showing limited information exchange between primary care physicians and chiropractors (Greene et al., 2007). Importantly, both provider groups valued the content shared in these records, whereas the medical doctors lacking record access expressed a preference for the exchange of such health information between providers rather than through patients. Operational efficiencies, such as integrated clinical records and secure messaging found in commercial electronic health records used within a single health care organization (Chen, Garrido, Chock, Okawa, & Liang, 2009), were not realized, a finding with workload implications for clinicians both in facilities with health information systems and those in solo or small group practices. Until electronic health records are exchanged securely and seamlessly between all settings, medical doctors and chiropractors might continue sharing patient care information through less “high-tech” means such as mailed or faxed treatment summaries. Of note, we did not share clinical records with patients. Health record access, such as My HealtheVet (Woods et al., 2013) and Patients Like Me (Wicks et al., 2010), improves patients’ understanding of their health conditions and perceptions of patient–provider communication. Back pain advice has had beneficial effects on fear avoidance behaviors and disability measures (Burton, Waddell, Tillotson, & Summerton, 1999). Future studies might evaluate how patient access to health records affects back pain outcomes.

Providers considered the older adults in this trial as change agents who helped drive the introduction of collaborative care in these settings (Mendel et al., 2008), which does differ from our initial conceptual framework which posited integrative medicine was a provider-driven model (Goertz et al., 2013; Hsiao et al., 2006). We published a case report from the trial to demonstrate how patients and providers can collaborate for more patientcentered approaches to LBP (Seidman, Vining, & Salsbury, 2015). Providers also noted more confidence when discussing the management of back pain with their patients (Supplementary Material and Table 2). Many studies have noted that chronic pain patients, and those with back pain in particular, do not experience patient-centered communication (Borkan et al., 1995; Gulbrandsen, Madsen, Benth, & Laerum, 2010; Walker, Holloway, & Sofaer, 1999). Our previous research showed older adults wanted chiropractors and primary care doctors to communicate both with each other, and with them, about back pain, and to involve patients in decision-making (Lyons et al., 2013). Thus, we are encouraged by provider reports that they talked with patients more about their spinal health and treatment options.

Integrative health care is difficult to achieve under the best of circumstances (Frenkel & Borkan, 2003; Gucciardi, Espin, Morganti, & Dorado, 2016; Sundberg, Halpin, Warenmark, & Falkenberg, 2007) and may be more challenging across health care organizations (Coulter, Ellison, Hilton, Rhodes, & Ryan, 2008). Along a continuum for models of team-based health care (Boon, Verhoef, O’Hara, & Findlay, 2004), the COCOA model is classified as a collaborative model. Higher level models, from coordinated to interdisciplinary to integrative care, may require a shared physical space, in addition to shared core values, patient-centered care, and institutional support (Boon et al., 2004). Health care organizations should realize that their older patients are interested in a one-stop approach to management of their musculoskeletal conditions and would value seeing their providers in shared appointments (Lyons et al., 2013).

This study had its limitations. Our clinicians noted that these older adults seemed more motivated to address their back pain than patients who seek care outside clinical trials. The family physicians were supervised residents, the chiropractors were employed in a research center, and neither clinician was the regular provider for participants. An anticipated limitation from the outset of the project was that residents would miss some presentations due to patient care schedules. Thus, the model may be more challenging to implement with providers working outside the unique settings where this study took place, and in practices where scheduling the time and personnel to support collaboration may differ. Not all clinicians participated in the interviews, which may suggest some response bias. Lastly, much of the patient care provided in this study was supported by a research grant, and we did not collect data about the costs associated with interprofessional education or model implementation. Older adults who are paying or co-paying for care and organizations that might have to invest capital to integrate these clinical practices will need to consider any associated costs.

Although site-specific tailoring and additional research on the implementation of this health care innovation is suggested for other real-world settings (Mendel et al., 2008), model components were feasible and transferrable to interprofessional practice between family medicine residents and chiropractors. The model supported interprofessional education about back pain, a common condition for which older adults seek health care from both these provider groups. Clinical record exchanges between the clinics were supported, and allowed for a modest level of team-based case management between clinicians working in two health systems with no history of interprofessional cooperation, most of whom had reported no previous experience collaborating with the other provider type. The findings here might be most transferrable within health care systems that employ both medical doctors and chiropractors. Training programs that introduce medical, osteopathic and chiropractic students to the approaches and treatments of the other disciplines might also improve interprofessional collaboration for older adults with back pain.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the older adults, providers, and study personnel who participated in the COCOA Study. We are grateful to the clinicians who presented at the interprofessional education sessions: Drs. John Stites, Michael Tunning, and Michael Seidman. We appreciate the contributions of Dr. Mark Jones on all aspects of this project. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (R18HP15126) and the National Institutes of Health National Center for Research Resources (C06-RR015433).

References:

Bailey, J., Pope, R., Elliott, E., Wan, J., Waters, T., & Frisse, M. (2013).

Health information exchange reduces repeated diagnostic imaging for back pain.

Annals of Emergency Medicine, 62, 16–24. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.01.006Bednarz, E., & Lisi, A. (2014).

A survey of interprofessional education in chiropractic continuing education in the United States.

Journal of Chiropractic Education, 28, 152–156. doi:10.7899/JCE-13-17Boon, H., Verhoef, M., O’Hara, D., & Findlay, B. (2004).

From parallel practice to integrative health care: A conceptual framework.

BMC Health Services Research, 4, 15. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-4-15Borkan, J., Reis, S., Hermoni, D., & Biderman, A. (1995).

Talking about the pain: A patient-centered study of low back pain in primary care.

Social Science and Medicine, 40, 977–988. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(94)00156-NBriggs, A., Cross, M., Hoy, D., Sánchez-Riera, L., Blyth, F., Woolf, A., & March, L. (2016).

Musculoskeletal health conditions represent a global threat to healthy aging: A report for the 2015 World Health Organization World Report on Ageing and Health.

The Gerontologist, 56, S243–S255. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw002Buchbinder, R., Staples, M., & Jolley, D. (2009).

Doctors with a special interest in back pain have poorer knowledge about how to treat back pain.

Spine, 34, 1218–1226. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e318195d688Burton, A., Waddell, G., Tillotson, K., & Summerton, N. (1999).

Information and advice to patients with back pain can have a positive effect:

A randomized controlled trial of a novel educational booklet in primary care.

Spine, 24, 2484–2491. doi:10.1097/00007632-199912010-00010Cayea, D., Perera, S., & Weiner, D. (2006).

Chronic low back pain in older adults: What physicians know, what they think they know, and what they should be taught.

Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 54, 1772–1777. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00883.xChen, C., Garrido, T., Chock, D., Okawa, G., & Liang, L. (2009).

The Kaiser Permanente Electronic Health Record: Transforming and streamlining modalities of care.

Health Affairs, 28, 323–333. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.323Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, Cross JT Jr., Shekelle P, Owens DK:

Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain: A Joint Clinical Practice Guideline

from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society

Annals of Internal Medicine 2007 (Oct 2); 147 (7): 478–491Christensen, M., Hyland, J., Goertz, C., & Kollasch, M. (2015).

Practice Analysis of Chiropractic 2015:

A project report, survey analysis, and summary of chiropractic practice in the United States.

Greely, CO: National Board of Chiropractic Examiners.Coulter, I., Ellison, M., Hilton, L., Rhodes, H., & Ryan, G. (2008).

Hospital-based integrative medicine: A case study of the barriers and factors facilitating the creation of a center.

Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.Docking, R., Fleming, J., Brayne, C., Zhao, J., Macfarlane, G., & Jones, G. (2011).

Epidemiology of back pain in older adults: Prevalence and risk factors for back pain onset.

Rheumatology, 50, 1645–1653. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ker175Frenkel, M., & Borkan, J. (2003).

An approach for integrating complementary-alternative medicine into primary care.

Family Practice, 20, 324–332. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmg315Goertz, C., Salsbury, S., Vining, R., Long, C., Andresen, A., Jones, M. et al. (2013).

Collaborative care for older adults with low back pain by family medicine physicians and doctors of chiropractic

(COCOA): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial.

Trials, 14, 18. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-14-18Gore M, Sadosky A, Stacey BR, Tai KS, Leslie D.

The Burden of Chronic Low Back Pain: Clinical Comorbidities, Treatment Patterns,

and Health Care Costs in Usual Care Settings

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012 (May 15); 37 (11): E668–677Greene, B., Smith, M., Haas, M., & Allareddy, V. (2007).

How often are physicians and chiropractors provided with patient information when accepting referrals?

Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 30, 344–346. doi:10.1097/01. JAC.0000290403.89284.e0Gucciardi, E., Espin, S., Morganti, A., & Dorado, L. (2016).

Exploring interprofessional collaboration during the integration of diabetes teams into primary care.

BMC Family Practice, 17, 1. doi:10.1186/s12875-016-0407-1Gulbrandsen, P., Madsen, H., Benth, J., & Laerum, E. (2010).

Health care providers communicate less well with patients with chronic low back pain:

A study of encounters at a back pain clinic in Denmark.

Pain, 150, 458–461. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.05.024Haldeman S, Dagenais S.

A Supermarket Approach to the Evidence-informed Management of Chronic Low Back Pain

Spine Journal 2008 (Jan); 8 (1): 1–7Hawk C, Schneider M, Dougherty P, Gleberzon BJ, Killinger LZ.

Best Practices Recommendations for Chiropractic Care

for Older Adults: Results of a Consensus Process

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2010 (Jul); 33 (6): 464–473Hsiao, A., Ryan, G., Hays, R., Coulter, I., Andersen, R., & Wenger, N. (2006).

Variations in provider conceptions of integrative medicine.

Social Science and Medicine, 62, 2973–2987. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.056Hsieh, H., & Shannon, S. (2005).

Three approaches to qualitative content analysis.

Qualitative Health Research, 15, 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687Karlin, B., & Karel, M. (2014).

National integration of mental health providers in VA home-based primary care:

An innovative model for mental health care delivery with older adults.

The Gerontologist, 54, 868–879. doi:10.1093/geront/gnt142Khorsan, R., Coulter, I., Hawk, C., & Choate, C. (2008).

Measures in chiropractic research: Choosing patient-based outcome assessments.

Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, 31, 355–375. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.04.007Löckenhoff, C., Laucks, S., Port, A., Tung, J., Wethington, E., & Reid, M. (2013).

Temporal horizons in pain management: Understanding the perspectives of physicians, physical therapists, and their middle-aged and older adult patients.

The Gerontologist, 53, 850–860. doi:10.1093/geront/gns136Lyons K, Salsbury S, Hondras M, Jones M, Andresen A, Goertz C.

Perspectives of Older Adults on Co-management of Low Back Pain by Doctors of Chiropractic

and Family Medicine Physicians: A Focus Group Study

BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013 (Sep 16); 13: 225Mainous, A., Gill, J., Zoller, J., & Wolman, M. (2000).

Fragmentation of patient care between chiropractors and family physicians.

Archives of Family Medicine, 9, 446–450. doi:10.1001/archfami.9.5.446Makris, U., Fraenkel, L., Han, L., Leo-Summers, L., & Gill, T. (2011).

Epidemiology of restricting back pain in communityliving older persons.

Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59, 610–614. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03329.xMakris, U., Higashi, R., Marks, E., Fraenkel, L., Sale, J., Gill, T. et al. (2015).

Ageism, negative attitudes, and competing co-morbidities - why older adults may not seek care

for restricting back pain: A qualitative study.

BMC Geriatrics, 15, 39. doi:10.1186/s12877-015-0042-zMcIntosh, A., & Shaw, C. (2003).

Barriers to patient information provision in primary care: Patients’ and general practitioners’ experiences and expectations of information for low back pain.

Health Expectations, 6, 19–29. doi:10.1046/j.1369-6513.2003.00197.xMendel, P., Meredith, L., Schoenbaum, M., Sherbourne, C., & Wells, K. (2008).

Interventions in organizational and community context: A framework for building evidence on dissemination and implementation in health services research.

Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 35, 21–37.

doi:10.1007/s10488-007-0144-9Ness, J., Cirillo, D., Weir, D., Nisly, N., & Wallace, R. (2005).

Use of complementary medicine in older Americans: Results from the Health and Retirement Study.

The Gerontologist, 45, 516–524. doi:10.1093/geront/45.4.516Parsons S, Harding G, Breen A, Foster N, Pincus T, Vogel S, et al.

Will Shared Decision Making Between Patients with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain

and Physiotherapists, Osteopaths and Chiropractors Improve Patient Care?

Fam Pract. 2012 (Apr); 29 (2): 203–212Patel, K., Guralnik, J., Dansie, E., & Turk, D. (2013).

Prevalence and impact of pain among older adults in the United States:

Findings from the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study.

Pain, 154, 2649–2657. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.029Penney LS, Ritenbaugh C, Elder C, Schneider J, Deyo RA, DeBar LL.

Primary Care Physicians, Acupuncture and Chiropractic Clinicians,

and Chronic Pain Patients: A Qualitative Analysis of

Communication and Care Coordination Patterns

BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016 (Jan 25); 16: 30Riva, J., Lam, J., Stanford, E., Moore, A., Endicott, A., & Krawchenko, I. (2010).

Interprofessional education through shadowing experiences in multi-disciplinary clinical settings.

Chiropractic & Osteopathy, 18, 31. doi:10.1186/1746-1340-18-31Roland, M., & Morris, R. (1983).

A study of the natural history of back pain. Part I: Development of a reliable and sensitive measure of

disability in low-back pain.

Spine, 8, 141–144. doi:10.1097/00007632-198303000-00005Scharlach, A., Graham, C., & Berridge, C. (2015).

An integrated model of co-ordinated community-based care.

The Gerontologist, 55, 677–687. doi:10.1093/geront/gnu075Seidman M, Vining R, Salsbury S.

Collaborative Care for a Patient with Complex Low Back Pain

and Long-term Tobacco Use: A Case Report

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2015 (Sep); 59 (3): 216–225Sherman, KJ, Cherkin, DC, Connelly, MT, Erro, J, Savetsky, JB, Davis, RB et al.

Complementary and Alternative Medical Therapies for Chronic Low Back Pain:

What Treatments Are Patients Willing To Try?

BMC Complement Altern Med. 2004 (Jul 19); 4: 9Sundberg, T., Halpin, J., Warenmark, A., & Falkenberg, T. (2007).

Towards a model for integrative medicine in Swedish primary care.

BMC Health Services Research, 7, 107. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-7-107Tracy, C., Bell, S., Nickell, L., Charles, J., & Upshur, R. (2013).

The IMPACT clinic innovative model of interprofessional primary care for elderly patients with complex health care needs.

Canadian Family Physician, 59, e148–e155.Walker, J., Holloway, I., & Sofaer, B. (1999).

In the system: The lived experience of chronic back pain from the perspectives of those seeking help from pain clinics.

Pain, 80, 621–628. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00254-1Weigel, PAM, Hockenberry, JM, Bentler, SE, Kaskie, B, and Wolinsky, FD.

Chiropractic Episodes and the Co-occurrence of Chiropractic

and Health Services Use Among Older Medicare Beneficiaries

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2012 (Mar); 35 (3): 168-175Weigel, P., Hockenberry, J., Bentler, S., & Wolinsky, F. (2013).

Chiropractic use and changes in health among older Medicare beneficiaries: A comparative effectiveness observational study.

Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, 36, 572–584. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2013.08.008Weigel P, Hockenberry J, Bentler S, Wolinsky F.

The Comparative Effect of Episodes of Chiropractic and Medical Treatment

on the Health of Older Adults

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2014 (Mar); 37 (3): 143–154Weigel, P., Hockenberry, J., & Wolinsky, F. (2014).

Chiropractic Use in the Medicare Population: Prevalence, Patterns, and Associations

With 1-year Changes in Health and Satisfaction With Care

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2014 (Mar); 37 (8): 542-551Weiner, D., Kim, Y., Bonino, P., & Wang, T. (2006).

Low back pain in older adults: Are we utilizing healthcare resources wisely?

Pain Medicine, 7, 143–150. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00112.xWeiner, D., Morone, N., Spallek, H., Karp, J., Schneider, M., Washburn, C. et al. (2014).

E-learning module on chronic low back pain in older adults: Evidence of effect on medical student o

bjective structured clinical examination performance.

Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 62, 1161–1167. doi:10.1111/jgs.12871Weiner, D., Sakamoto, S., Perera, S., & Breuer, P. (2006).

Chronic low back pain in older adults: Prevalence, reliability, and validity of physical examination findings.

Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 54, 11–20. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00534.xWhedon, J., Mackenzie, T., Phillips, R., & Lurie, J. (2015).

Risk of traumatic injury associated with chiropractic spinal manipulation in Medicare Part B beneficiaries aged 66–99.

Spine, 40, 264–270. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000725Wicks, P., Massagli, M., Frost, J., Brownstein, C., Okun, S., Vaughan, T. et al. (2010).

Sharing health data for better outcomes on PatientsLikeMe.

Journal of Medical Internet Research, 12, e19. doi:10.2196/jmir.1549Wong, J., Di Loreto, L., Kara, A., Yu, K., Mattia, A., Soave, D. et al. (2014).

Assessing the change in attitudes, knowledge, and perspectives of medical students towards chiropractic

after an educational intervention.

Journal of Chiropractic Education, 28, 112–122. doi:10.7899/JCE-14–16Woods, S. S., Schwartz, E., Tuepker, A., Press, N. A., Nazi, K. M., Turvey, C. L. et al. (2013).

Patient experiences with full electronic access to health records and clinical notes through the My HealtheVet Personal Health Record Pilot: Qualitative study.

Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15, e65. doi:10.2196/jmir.2356

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return to INTEGRATED HEALTH CARE

Since 1-15-2017

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |