Clinical Outcomes in a Large Cohort of Musculoskeletal

Patients Undergoing Chiropractic Care in the

United Kingdom: A Comparison of Self- and

National Health Service-Referred RoutesThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2016 (Jan); 39 (1): 54–62 ~

OPEN ACCESS Jonathan R Field, MSc, DC • Dave Newell, PhD

Director of Research,

Anglo-European College of Chiropractic,

Bournemouth, UK.

Objective: An innovative commissioning pathway has recently been introduced in the United Kingdom allowing chiropractic organizations to provide state-funded chiropractic care to patients through referral from National Health Service (NHS) primary care physicians. The purpose of this study was to examine the outcomes of NHS and private patient groups presenting with musculoskeletal conditions to chiropractors under the Any Qualified Provider scheme and compare the clinical outcomes of these patients with those presenting privately.

Methods: A prospective cohort design monitoring patient outcomes comparing self-referring and NHS-referred patients undergoing chiropractic care was used. The primary outcome was the change in Bournemouth Questionnaire scores. Within- and between-group analyses were performed to explore differences between outcomes with additional analysis of subgroups as categorized by the STarT back tool .

Results: A total of 8,222 patients filled in baseline questionnaires. Of these, NHS patients (41%) had more adverse health measures at baseline and went on to receive more treatment. Using percent change in Bournemouth Questionnaire scores categorized at minimal clinical change cutoffs and adjusting for baseline differences, patients with low back and neck pain presenting privately are more likely to report improvement within 2 weeks and to have slightly better outcomes at 90 days. However, these patients were more likely to be attending consultations beyond 30 days.

Conclusions: This study supports the contention that chiropractic services as provided in United Kingdom are appropriate for both private and NHS-referred patient groups and should be considered when general medical physicians make decisions concerning referral routes and pain pathways for patients with musculoskeletal conditions.

Keywords: Chiropractic; Health Services Evaluation; Musculoskeletal Pain; Patient Outcome Assessment.

From the Article:

Background

Musculoskeletal conditions are common in all countries and cultures and are a major burden on health system. [1] In the next 50 years, this burden is predicted to increase as the population ages and public health issues such as obesity and lack of activity take their toll. [2]

In the United Kingdom (UK), back pain accounts for 4.8% of all social benefit claims [3] with the overall cost of musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions estimated at £5 to 7 billion per year and the number of general medical physician (GP) visits estimated at more than 30% of all consultations. [4] As national health systems strive to accommodate increasing demands and resources are stretched, the direct and indirect costs of shouldering the MSK burden are increasingly considered a national priority in the UK and in other developed economies.

Historically, in the UK, MSK conditions have been managed predominantly within the state health care system, although successive governments have attempted to bolster the contribution of the private (ie, independent) sector by providing funded access for patients to care normally considered to be outside the state system. Traditionally, outpatient MSK services have been provided by single large organizations covering 1 or more National Health Service (NHS) region. In the “new” NHS England, MSK care is envisaged to focus more on outcomes rather than targets and to be more patient focused, with greater empowerment, individualized plans, and evidence-based pathways in care choice as well as extending the freedom of payers to commission new services. [5]

An example of recent changes in such service provision was the development of contracts whereby independent or state sector organizations able to demonstrate achieving a priori excellence and clinical governance criteria as set by the UK government were able to apply to provide care funded by the NHS. These were termed Any Qualified Provider (AQP) contracts, and for the first time, they enabled organizations providing chiropractic services to accept and be remunerated for patient care as referred from primary care physicians (ie, general medical practitioners [GPs]) within particular NHS regions. These patients' health care treatments are paid for by the NHS through a set tariff not related to the number of treatments.

Previous research suggests that demographic and condition-based differences exist between private and state-funded patients with MSK conditions, with state-funded patients being somewhat less healthy (eg, greater severity, duration, and comorbidity) than private patients. [6] However, it is not known if these differences affect response to chiropractic care.

In addition, pretreatment screening of patients with nonspecific low back pain (LBP) using the STarT Back Screening Tool (SBT) has been developed and is intended to help GPs, and others direct such patients to targeted treatment. [7] Given that its use has increasingly been included in NHS back pain pathways, the authors have described the prognostic utility of this tool in patients presenting privately for chiropractic care. [8] However, little is known about the utility of SBT for patients seeking chiropractic care through state-funded services

The purpose of this study was to examine the outcomes of NHS and private patient groups presenting with MSK conditions to chiropractors under the AQP scheme and compare the clinical outcomes of these patients with those who presented privately. A second purpose was to examine the differential outcomes of patients with LBP who were classified as low, medium, and high risk of not improving by the STarT Back stratification tool in both patient groups.

Methods

Participants

The design of the study was observational using routinely collected data from patients over the age of 16 years at a consortium of UK-based practices located in the south of the UK. These clinics, in addition to providing care for private self-referring patients, also provided services to the NHS through an AQP contract with NHS patients being referred by local GPs.

Data Collection

Patient characteristics and outcomes were collected via a Web-based patient-reported outcome measure collection system (Care Response, https://www.care-response.com/CareResponse/home.aspx). This methodology has been developed to provide validated measures to patients by e-mail links sent automatically at set follow-up time points throughout and beyond the provision of face-to-face care. Using this system, baseline data that included patient- and condition-related characteristics, SBT, and the Bournemouth Questionnaire (BQ) were collected before the first visit using either the patients' e-mail collected by consent during the initial booking or at the clinic before the first appointment. Patients could designate areas of pain according to a pain manikin diagram and were able to indicate more than one area. Care Response enables exporting of anonymized information from participating practices to a secure encrypted server, thus facilitating collation and analysis of large sets of data collected as part of normal practice activity.

Patient-Reported Outcomes

The BQ is a condition-specific outcome measure and has been extensively validated and characterized. [9-12]

It consists of seven 11-point numerical rating scales (0-10) each covering a different aspect of the back pain experience. These were(i) pain,

(ii) disability in activities of daily living,

(iii) disability in social activity,

(iv) anxiety,

(v) depression,

(vi) fear avoidance behavior, and

(vii) locus of control.Subscales are summed to produce a total BQ score (maximum of 70).

Using the Patients' Global Impression of Change (PGIC), patients were asked “How would you describe your pain/complaint now, compared to how you were when you completed the questionnaire before your first visit to this clinic?” The scale ranges from 1 (worse than ever) to 7 (very much improved). This outcome was dichotomized for each of the follow-up points with improvement being defined by a PGIC response of better or much better (score of ≥6). [13]

The BQ and a PGIC were collected at 14, 30, and 90 days after the initial visit. In addition, participants also completed a 7-point Likert scale measuring satisfaction at the 30-day follow-up. The satisfaction scale consisted of 7 items and was preceded by a question asking “Overall, how have you found the service and care your received? This would include the way you have been treated by our reception, practitioners or any other contact from us.

Please select one of the following”:(1) unacceptably poor;

(2) not as good as I was expecting, I would be concerned if a friend wanted to come to you;

(3) reasonable but nothing special;

(4) as I was expecting and I am satisfied with this;

(5) better than I was expecting;

(6) good, I would be happy to recommend to a friend to you; and

(7) a very high level, I would recommend friends with similar problems to consider.Analysis

For all participants, baseline and follow up data were analyzed using descriptive statistics with comparisons between groups using appropriate inferential methods. Bournemouth Questionnaire percent change scores were calculated using the following formula: (follow-up score-baseline score/baseline score) × 100. [11]

For LBP and neck pain (NP) patients only, further categorization of BQ percent change scores was calculated. We chose the minimal clinical important change cutoff points for back pain and NP subjects of greater than and equal to 46% or greater than and equal to 35%, respectively. [11, 12]

Within- and between-group analyses were investigated using repeated-measures general linear methods (GLM) with adjustment for significant baseline differences between groups with change in percentage of total BQ scores as the dependent variable. Time interactions were also included. Regression models were constructed using the dichotomized PGIC as the dependent variable (where improvement was determined as ≥6 points) for each follow-up point and within the NHS or self-referral groups. An identical analysis was also carried out with dichotomized percent change in BQ scores as the dependent variable. A forward likelihood ratio logistic regression procedure was used for this purpose.

For the subgroup analysis, we analyzed only nonspecific lower back pain patients who had been categorized as low, medium, and high risk by the SBT. Within- and between-group analyses were carried out using GLM as above with the grouping variable set as NHS or private patients. In addition, we also generated crude and adjusted odds ratios for the likelihood of improvement in self-referring patients as compared to NHS patients as defined by dichotomized PGIC outcomes (≥6 points) within each of the SBT risk group categories. For this, we used a logistic regression procedure adjusting for all baseline variables indicated as significantly different between these 2 referral routes.

Ethics

The Anglo-European College of Chiropractic ethics board confirmed that this service evaluation study was exempt from institutional ethical review (http://www.aecc.ac.uk/research/about/).

Results

Baseline Descriptors

Table 1

Table 2+3

See page 4

Table 4-9

See page 5A total of 8,222 patients completed the initial questionnaire. Of these, 41% were NHS patients referred by their GP. Table 1 describes the characteristics of this cohort of patients at baseline as split into NHS and private patient groups. The greatest proportion of patients indicated either back pain, NP, or both as an area of pain.

Comparison of groups showed significant differences across a range of both demographic and clinical measures. The NHS patients were more likely to be female, more chronic, and have higher severity including radiating pain and have a higher BQ scores across all domains (Table 1). Of those patients who identified low back, NP, or both as an area of pain, similar differences between NHS and private patients were seen as with the whole cohort (Tables 2 and 3).

Specifically for patients with LBP, NHS patients were significantly more likely to be placed in the high-risk SBT group (39.1% vs 21.6%), whereas similar proportions were classed as medium risk (Table 2).

Outcomes

Both private and NHS patients referred for LBP and NP showed substantial improvement across the range of outcome assessments at each of the 3 follow-up points (Tables 4–7). Using the published cutoff for minimally clinically important change (MCIC) in percent change BQ, a smaller proportion of NHS LBP patients achieved important clinical change over the course of the treatment as compared to private patients (Table 4). This is most marked in the initial 2 weeks from after the initial consultation. Crude odds ratios indicate that overall NHS patients were around 2 to 3 times less likely to improve in comparison to private patients. However, when adjusting for key baseline confounders, these differences became insignificant at 1-month follow-up re-emerging at 90 days. Using the PGIC as a dichotomized outcome, ostensibly identical results emerged, although these 2 measures are substantially different, one being a summed score across multiple condition-based and psychological domains questioning how the patient feels now and the other a 7-point scale asking individuals about their perception of improvement thinking back to how they were when they initially presented.

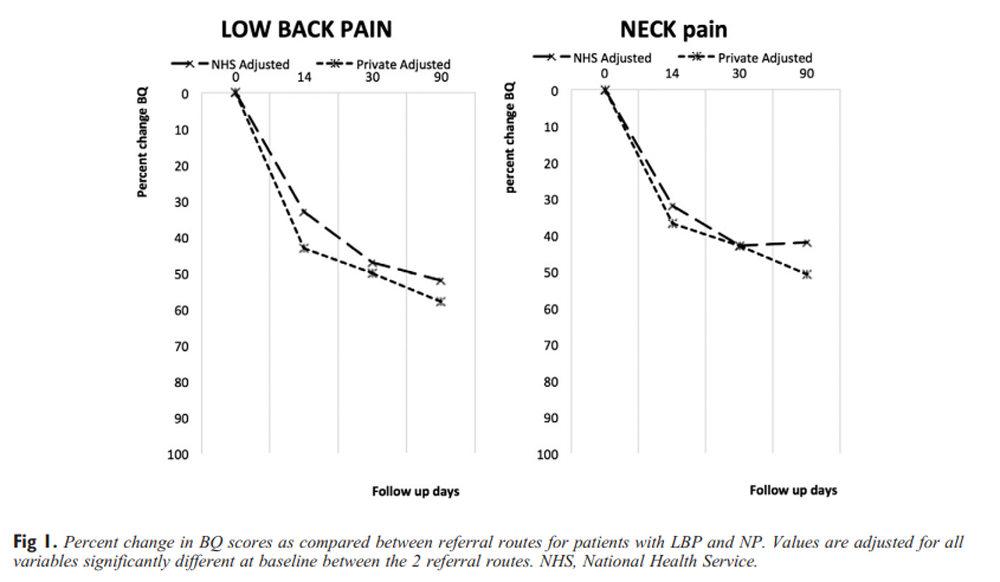

Figure 1 When adjusted for baseline confounders, differences in percent change in BQ scores for patients with LBP in the 2 referral groups remained significant only up to 2 weeks into treatment (Table 5 and Fig 1A). Differences were minimal at 1 month but increased slightly at 90 days. However, this remained statistically insignificant. Mean response profiles as determined by analysis of time/group interaction was statistically insignificant over time between groups (F = 0.75; P > .05) indicating the pattern of change was essentially the same between the 2 referral groups.

For patients with NP, a similar pattern in the risk of improvement is apparent both in terms of MCIC for the BQ and the PGIC (Table 6). After adjusting for key baseline differences, the differences in outcomes were not statistically significant after 2 weeks of chiropractic care. This is more apparent in the adjusted change in percent BQ scores where there was no substantive difference in adjusted changes scores at any follow-up point (Table 7 and Fig 1B).

Table 8 shows that there were significant differences between the number of treatments for each group over time with NHS patients receiving more sessions over a shorter time, having effectively ended treatment by 30 days, whereas private patients were still attending for further consultations. The number of treatments received by those presenting with either LBP or NP was similar.

Most patients in both groups reported being satisfied with the care they had received (Table 9). National Health Service patients were more likely to have had their expectations exceeded than private patients (98.5% vs 89.2%).

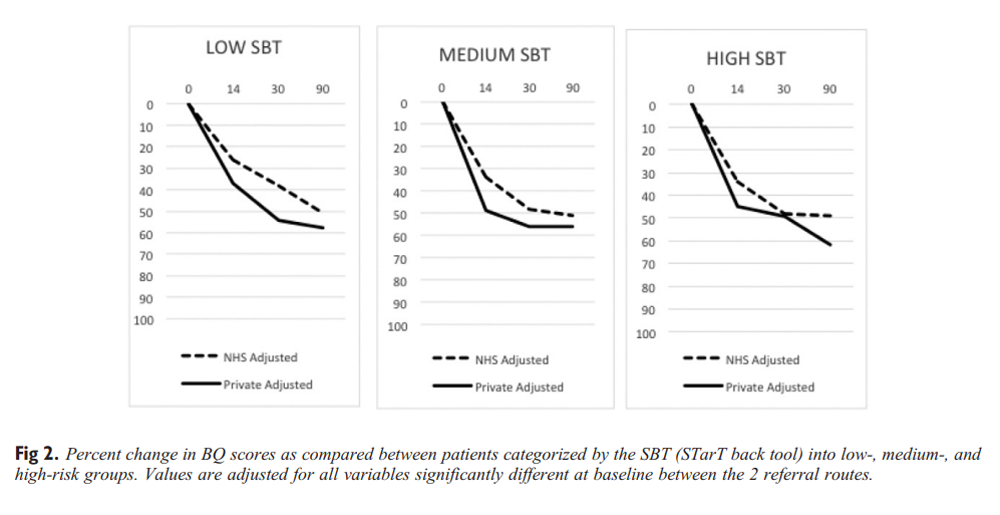

STarT Back Categorization

Figure 2 A GLM analysis was carried out for between- and within-group and time multiplied by group interactions for percent change in BQ scores as adjusted for the same baseline variables as in the whole cohort back pain analysis above (Figure 2). In the low-risk group, there were no significant group or group multiplied by time interactions, although both groups changed significantly over time (F = 5.3; P < .01). However, in both medium- and high-risk groups, both group (medium [F = 5.4; P < .05] and high [F = 5.3; P < .05]) and time (medium [F = 5.9; P < .01] and high [F = 8.3; P < .001]) effects were significant with NHS, although as percentage outcomes, these effects did not persist at 90 days except in the high-risk groups. In terms of clinical change, around 80% of private patients and 60% to 70% of NHS patients achieved a minimally important change of 30% by 90-day follow-up.

Discussion

This study analyzed a large data set of patients with MSK conditions seeking chiropractic care either as self-referring private patients or as referred through the NHS via a GP. This is one of the largest prospective cohort studies of patients undergoing chiropractic care, and reporting of the characteristics and outcomes of patients presenting for such a large group of patients is unique in the UK. Results of this study are similar to other UK studies,8,14 and the descriptions of both baseline characteristics and outcomes may provide robust condition-specific metrics generalizable to the wider UK populations of patients presenting for private and NHS chiropractic care.

Generally, NHS patients were more chronic, in more distress, and displayed more comorbidity than private patients. Private patients, who are a self-selecting group, tend to be healthier and less severe at the time of presentation. Similar differences were found between chiropractic patients and those in general practice at baseline in a recent report from Denmark.6 Analysis of secondary data in the present study showed that those presenting privately are more likely to have had previous experiences of chiropractic care. This bolsters the idea that patients return for such care when presented with future MSK episodes.

On average, NHS patients attended more treatment sessions than those attending privately. The AQP contracts provide a fixed tariff for a course of care to the NHS patient irrespective of the number of sessions, whereas private patients pay per visit. We do not have information about compliance with clinicians care plans; therefore, it is possible that private patients were unwilling to attend as many sessions. However, given that as a group their care was extended over a longer period, a more likely explanation is that differences in visit numbers were not due to financial factors but more likely related to the more complicated health needs of the NHS patients.

Despite the more chronic and complex nature of the presentation of NHS patients, it was more common for private patients to continue to receive care beyond 30 days. However, the NHS pathways preclude providing supportive care beyond settling symptoms. In a physiotherapy setting in Ireland, public setting patients had more treatments than those who were self-referring.15 However, in the study by Casserley-Feeneya et al,15 there was no upper limit on public-funded treatments, and it is unknown whether removing such an artificial barrier in this study might ameliorate any differences seen in treatment numbers.

For patients with low back and NP, both private and NHS patients experienced large and clinically significant reductions in percent change BQ scores. When corrected for baseline differences in severity of symptoms, there were no significant differences between the private and NHS patients at 30 days, a small difference at 90 days, but this was only for patients with NP. Private patients as a group continued to improve at each follow-up assessment, whereas the improvement of the NHS group leveled off or slightly deteriorated after 30 days.

When dichotomizing the change in BQ scores as determined by a minimal clinical cutoff point for both back and NP, large proportions of patients were categorized as having clinically important improvement over the course of the 90 days, although fewer NHS patients fell into this category. However, after adjusting for baseline severity, statistically significant differences in odds of improvement only remained at early and later follow-up points in LBP patients and only at early follow-up in NP patients.

These proportions were mirrored by a global impression of change outcome as reported by the patient directly, indicating improvement anchored to the phrases “improved” or “very much improved.” Given that the MCIC as calculated in previous studies used a similar PGIC to determine such cutoff points, this might be expected. However, the large proportion of patients reporting important clinical change is notable over the course of this cohort care.

Generally, when looking at SBT risk groups, NHS patients in medium- and high-risk groups did less well, with this difference being marginally more marked in medium- and high-risk groups. However, these differences, although being statistically significant, were clinically small with most patients achieving clinical change in both referral groups by 90 days. This similarity in outcomes for SBT groups of patients undergoing chiropractic care has been reported before.16

The large majority of patients sampled here reported being satisfied with the care they received even if they did not achieve a positive outcome. This is in concord with prior work on patients' descriptions of their experiences having attended chiropractors.17 In this study, those referred by their GP were more likely to have had their expectations of treatment exceeded. There are differences in the care provided to the 2 groups with NHS patient's attending more sessions, which may account for this. In addition, higher proportions of private patients had previously seen a chiropractor and so are likely to have appropriate expectations of how they will be treated. It is possible that, in general, those paying for private care expect a different standard of service than those whose care is funded by the state.

The pattern of change in patients in this cohort is similar to other studies18 and mirrors the expected clinical course for LBP at least. In addition, a secondary analysis of expected regressions to the mean values as calculated using R2 regression coefficients between baseline and follow-up total BQ scores19 was marked indicating that this phenomena probably contributed, along with natural history20,21 and treatment effects to the changes seen in BQ scores over time, although these were generally smaller in the NHS group.

There was a deterioration of outcomes noted in the NHS group after they had finished attending for treatment (by 30 days), whereas further improvement was seen in the private group who were more likely to continue care beyond this. Previous work has suggested that prolonged treatments in the form of supported or maintenance care improve longer term prognosis.22,23 National Health Service patients received more sessions but, at higher frequency, early in care, and this may suggest that duration of care is a significant factor separate from number of visits. Further work is needed in this area.

Limitations and Strengths

The size of the cohort of this study is a strength. The use of an automatic electronic patient-driven patient-reported outcome measure system within the participating clinic directly facilitates the ability to collect such large numbers.

This study design precludes any conclusions regarding putative treatment effects associated with chiropractic care as factors including regression to the mean or natural history may underlie a significant proportion of the improvements seen. In addition, NHS-referred patients in this sample have been subject to selection by their GP and, as such, may not represent all those presenting with spinal pain to GPs, limiting generalizability to this wider population.

Furthermore, it is possible that the higher proportion of NHS patients indicating care had exceeded expectations may have had differing expectations of care compared to self-referring patents and the history and experience within a different health care setting may have influenced self-reporting of these outcomes.

Lastly, patients were recruited from a limited group of clinics in the south of England, and it is possible that demographic and condition-specific characteristics may be different in other parts of the UK or for other countries.

Conclusion

This study characterized a large number of private and NHS-referred patients as cared for by chiropractors and provides a unique and robust description of characteristics and outcomes in this patient group for the UK. Those presenting for chiropractic care either privately or by their NHS GP experienced excellent results across a range of patient-reported outcome and experience measures. This remained true regardless of the STarT back category where substantive improvements in outcomes were seen in all 3 risk groups regardless of referral status.

Practical Applications

This study characterized a large number of private and NHS-referred patients as cared for by chiropractors and provides a reliable description of this group in the UK.

Those presenting for chiropractic care, either privately or via their NHS GP, experienced excellent outcomes across a range of patient-reported outcome and experience measures.

This study supports the contention that chiropractic services as provided in UK are appropriate for both private and NHS-referred patient groups and should be considered when GPs make decisions concerning referral routes and pain pathways for MSK patients.

Funding Sources and Potential Conflicts of Interest

No funding sources or conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

Contributorship Information

Concept development (provided idea for the research): J.F. and D.N.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): J.F. and D.N.

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript): J.F.

Data collection/processing (responsible for experiments, patient management, organization, or reporting data): J.F.

Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results): D.N.

Literature search (performed the literature search): J.F. and D.N.

Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): J.F. and D.N.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking): J.F. and D.N.

References:

Becker, A, Held, H, Redaelli, M

Low back pain in primary care: costs of care and prediction

of future health care utilization

Spine. 2010; 35:1714-1720Ellis, B, Silman, A, Loftis, T

Musculoskeletal health: a public health approach

Copeman House, Arthritis Research UK, 2014Public Health England.

Obesity and disability

Public Health England, London, 2013 [Available from:

http://www.noo.org.uk/uploads/doc/vid_18474_obesity_dis.pdf

(Accessed: 26 February 2013)]Department of Health (DH)

The Musculoskeletal Services Framework

The department, London, 2006Ham, C, Baird, B, Gregory, S

The NHS under the coalition government: part 1—NHS reform

The King's Fund, London, 2015 [Available from:

http://www.nhshistory.net/kingsfund%20reforms.pdf

(Accessed: 27 February 2013)]Hestbaek, L, Munck, A, Hartvigsen, L

Low Back Pain in Primary Care: A Description

of 1250 Patients with Low Back Pain in Danish

General and Chiropractic Practice

Int J Family Med. 2014 (Nov 4); 2014: 106102Hill, JC, Dunn, KM, Lewis, M

A Primary Care Back Pain Screening Tool:

Identifying Patient Subgroups For Initial Treatment

(The STarT Back Screening Tool)

Arthritis Rheum. 2008 (May 15); 59 (5): 632–641Field, J, Newell, D

Relationship Between STarT Back Screening Tool and Prognosis

for Low Back Pain Patients Receiving Spinal Manipulative Therapy

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2012 (Jun 12); 20 (1): 17Bolton, J, Breen, A

The Bournemouth Questionnaire:

A Short-form Comprehensive Outcome Measure.

I. Psychometric Properties in Back Pain Patients

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1999 (Oct); 22 (8): 503-510Bolton, J, Humphreys, B

The Bournemouth Questionnaire:

A Short-form Comprehensive Outcome Measure.

II. Psychometric Properties in Neck Pain Patients

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2002 (Mar); 25 (3): 141-148Hurst, H, Bolton, J

Assessing the Clinical Significance of Change Scores

Recorded on Subjective Outcome Measures

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2004 (Jan); 27 (1): 26–35Bolton, J

Sensitivity And Specificity Of Outcome Measures In Patients With

Neck Pain: Detecting Clinically Significant Improvement

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004 (Nov 1); 29 (21): 2410-2417Newell, D, Bolton, J

Responsiveness of the Bournemouth questionnaire in determining minimal

clinically important change in subgroups of low back pain patients

Spine. 2010; 35:1801-1806Gurden, M, Morelli, M, Sharp, G

Evaluation of a general practitioner referral service

for manual treatment of back and neck pain

Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2012; 13:204-210Casserley-Feeneya, S, Buryb, B, Dalyc, L

Physiotherapy for low back pain: differences between public and

private healthcare sectors in Ireland—a retrospective survey

Man Ther. 2008; 13:441-449Newell, D, Field, J, Pollard, D

Using the STarT back tool: does timing of stratification matter?

Man Ther. 2015; 20:533-539Hurwitz, E, Morgenstern, H, Yu, F

Satisfaction as a Predictor of Clinical Outcomes Among

Chiropractic and Medical Patients Enrolled in

the UCLA Low Back Pain Study

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005 (Oct 1); 30 (19): 2121–2128Artus, M, de Windt, D, Jordan, K

The clinical course of low back pain: a meta-analysis comparing outcomes

in randomised clinical trials (RCTs) and observational studies

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014; 15:68Barnett, A, van der Pols, J, Dobson, J

Regression to the mean: what it is and how to deal with it

Int J Epidemiol. 2005; 34:215-220Hestbaek, L, Leboeuf-Yde, C, Engberg, M

The Course of Low Back Pain in a General Population.

Results From a 5-year Prospective Study

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003 (May); 26 (4): 213–219Pengel, LHM, Herbert, RD, Maher, CG

Acute low back pain: systematic review of its prognosis

BMJ. 2003; 327:323Descarreaux, M, Blouin, JS, Drolet, M

Efficacy of Preventive Spinal Manipulation for Chronic Low-Back

Pain and Related Disabilities: A Preliminary Study

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2004 (Oct); 27 (8): 509–514Senna, M, Machaly, S

Does Maintained Spinal Manipulation Therapy

for Chronic Non-specific Low Back Pain

Result in Better Long Term Outcome?

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011 (Aug 15); 36 (18): 1427–1437

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return to CHRONIC NECK PAIN

Return to INITIAL PROVIDER/FIRST CONTACT

Since 2-15-2025

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |