Importance of the Type of Provider Seen to Begin

Health Care for a New Episode Low Back Pain:

Associations with Future Utilization and CostsThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Eval Clin Pract. 2016 (Apr); 22 (2): 247–252 ~ FULL TEXT

Julie M. Fritz PhD PT FAPTA, Jaewhan Kim PhD, and Josette Dorius BSN MPH

Department of Physical Therapy,

College of Health,

University of Utah,

Salt Lake City, UT, USA.

Editorial Comment

This article is the perfect example of how mis-leading an Abstract can be,

when it fails to reflect what the study actually reveals. (see it below)

The RESULTS portion of this Abstract only partially discusses the findings, comparing 3 different professions' treatment, costs, and outcomes for low back pain.

In it they only mention the costs associated with medical management, while in reviewing chiropractic care vs. physical thereapy portions, they choose to emphasize:Entry in chiropractic was associated with

an increased episode of care duration

Entry in physical therapy

no patient entering in physical therapy had surgery.That *seems* to suggest that physical therapy *may* entail less expense, or shorter durations of care, or that chiropractic patients are more likely to end up with surgery. None of that is true. Their own Table 2 plainly reveals that chiropractic care was the least expensive form of care provided to the 3 groups.

More recently Blanchette et al. [1] found, while reviewing 5,511 cases of workers who received compensation, that:

“The type of healthcare provider first visited for back pain is a determinant of the duration of financial compensation during the first 5 months. Chiropractic patients experience the shortest duration of compensation, while physiotherapy patients experience the longest. These differences raise concerns regarding the use of physiotherapists as gatekeepers for the worker's compensation system.”

1. Association Between the Type of First Healthcare Provider and the Duration of Financial Compensation

for Occupational Back Pain

Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 2017 (Sep); 27 (3): 382–392

In case you are wondering what's bugging me, meta-analyses and other types of reviews always start by looking for Abstracts that fulfill their search criteria. This abstract does NOT suggest that chiroptactic is less costly (even though it was).

Even more insultingly, in the DISCUSSION section, they slip in just a bit more deception:

Can you hear my blood boil yet? The proper terminology for a chiropractor is “Doctor of Chiropractic”, not a “non-doctor provider such as a physical therapist”“More specifically, existing studies suggest there may be reduced exposure to expensive and invasive procedures and lower costs when a non-doctor provider such as a physical therapist or chiropractor is the initial provider...”

Clearly they smell blood in the water.

In the future, some profession WILL become the Gatekeeper for patients with low back pain, and this article tries to suggest that PTs should stand, hand-in-hand, with chiropractors in that doorway.

I don't think so.

Chiropractors take almost 1000 hours of classes devoted spinal manipulation techniques, out of a 4,200 hour doctoral program. How many manipulative hours did PTs recieve, and who did they recieve it from?

The University of Utah Department of Physical Therapy website does not say. Hmmm?RATIONALE, AIMS AND OBJECTIVE: Low back pain (LBP) care can involve many providers. The provider chosen for entry into care may predict future health care utilization and costs. The objective of this study was to explore associations between entry settings and future LBP-related utilization and costs.

METHODS: A retrospective review of claims data identified new entries into health care for LBP. We examined the year after entry to identify utilization outcomes (imaging, surgeon or emergency visits, injections, surgery) and total LBP-related costs. Multivariate models with inverse probability weighting on propensity scores were used to evaluate relationships between utilization and cost outcomes with entry setting.

RESULTS: 747 patients were identified (mean age = 38.2 (± 10.7) years, 61.2% female). Entry setting was primary care (n = 409, 54.8%), chiropractic (n = 207, 27.7%), physiatry (n = 83, 11.1%) and physical therapy (n = 48, 6.4%).

Relative to primary care, entry in physiatry increased risk forradiographs (OR = 3.46, P = 0.001),

advanced imaging (OR = 3.38, P < 0.001),

injections (OR = 4.91, P < 0.001),

surgery (OR = 4.76, P = 0.012)

and LBP-related costs (standardized B = 0.67, P < 0.001).Entry in chiropractic was associated with decreased risk for

advanced imaging (OR = 0.21, P = 0.001)

or a surgeon visit (OR = 0.13, P = 0.005)

and increased episode of care duration (standardized B = 0.51, P < 0.001).Entry in physical therapy decreased risk of

radiographs (OR = 0.39, P = 0.017)

and no patient entering in physical therapy had surgery.CONCLUSIONS: Entry setting for LBP was associated with future health care utilization and costs. Consideration of where patients chose to enter care may be a strategy to improve outcomes and reduce costs.

KEYWORDS: care pathways; economic analysis; health care utilization; health services research; low back pain

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) impacts 60–80% of individuals at some in their lives. [1, 2] Management imposes a large socio-economic burden on health care systems. Total direct costs in the United States were estimated at over 86 billion dollars in 2005 [3] and costs related to LBP have been increasing at a rate faster than overall health care spending. [3, 4]

Given the prevalence of LBP it is not surprising that it ranks as the second or third most common symptomatic conditions for which an individual seeks health care. [5–7] An estimated one of every 17 doctor visits are attributable to LBP [6] across several specialties, and LBP is the most common condition encountered in physical therapy and chiropractic practices. [8–10] Considering the number of providers involved and the myriad management options, it is not surprising that care patterns for LBP are highly variable. [11–15] Fragmented and variable care for LBP contributes to high levels of guideline discordant management, overuse of expensive and invasive procedures, and continual cost escalations without accompanying evidence of improved outcomes [16–18].

Research increasingly points to the importance of early care decisions and guideline adherence in the prognosis of patients with LBP who seek care. For example, ordering a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or prescribing opioids within the first weeks is associated with increased risk for persistent symptoms, work disability and high costs. [19–23] Less attention has focused on the earliest care decision made by a patient, the type of provider selected to begin care. This decision likely has important implications for the prognosis and costs associated with an episode of LBP care. [24] Numerous provider types including several doctor specialties, physical therapists and chiropractors may serve as the point of entry for an individual with LBP. More research is needed to explore the implications of beginning care with different providers.

The purposes of this study were(1) describe the entry providers chosen by individuals with private health insurance for a new LBP consultation,

(2) examine differences in patient characteristics based on entry setting and

(3) examine associations between entry setting and duration of episode of care, subsequent health care costs and risk for utilization of specific procedures including radiographs, advanced imaging, injections, emergency department or spine surgeon visits, or surgery for LBP.

Methods

Data and study sample

We conducted a retrospective study of new LBP consultations between 1 January 2012 and 31 January 2013 using claims data from the University of Utah Health Plans (UUHP). The UUHP is a non-profit insurer and integrated subsidiary of University of Utah Health Care. We included enrollees with private, employer-based, coverage between the ages of 18 and 60. A new LBP consultation was defined as a provider visit occurring during the inclusion dates associated with a LBP-related ICD-9 code (720.2, 721.3, 722.1, 722.52, 722.73, 722.93, 724.×, 739.3, 739.4, 756.11, 756.12, 846.×, 847.2, 847.3, 847.9) as a primary or secondary diagnosis for whom no charges associated with LBP were received in the prior 90 days. Date of the new consultation was defined as the entry visit. We excluded those not continuously enrolled with UUHPfor at least 90 days preceding and 1 year following the entry visit. We excluded patients presenting at the entry visit with an ICD-9 code indicative of a possible non-musculoskeletal cause for back pain including kidney (592.×) or gall bladder stone (574.×), urinary tract infection (599.0), or patients with a red flag condition that may require urgent management including spinal/pelvis fracture (805.×–809.×, 820.×–821.×, 733.13–733.15 or 733.96– 733.98), osteomyelitis (733.×), ankylosing spondylitis (720.0), cauda equina syndrome (344.6×) or any malignant neoplasm (140.×–209.×) diagnosis at the entry visit. Each patient was included only once in the analysis based on the first eligible entry visit using the above criteria.

Independent variables

Based on the procedure code and provider associated with the entry visit, we categorized the entry setting as(1) primary care (family medicine, internal medicine, obstetrics/gynaecology),

(2) physiatry,

(3) chiropractic,

(4) physical therapy,

(5) spine surgeon (orthopedic or neurosurgeon),

(6) emergency department or

(7) other doctor specialty (e.g. rheumatologist, neurologist, etc.).The UUHP and state of Utah allow access to these providers without prior authorization requirement.

Patient characteristics and covariates

We identified patient characteristics and co-morbid conditions from UUHP enrolment information, the University of Utah Health Care electronic medical record (EMR) and ICD-9 codes for all claims recorded in the year following the entry visit. Patient characteristics included sex, age, zip code of residence and LBP as primary or secondary diagnosis at entry visit. Specific co-morbidities recorded were mental health conditions (296.×, 297.×, 298.×, 300.×, 301.×, 308.×, 309.×, 311.×), smoking status (305.1, V15.82, 649.0×), substance use disorders (291.×, 303.×– 304.×, 305.0, 305.2×–305.9×), chronic pain (338.×) prior lumbar surgery (V45.4, 722.83) and obesity (278.×). We computed the Charlson Co-Morbidity Index (CCI) [25], which was dichotomized as low (≤1) or high (≥2).

Dependent variables

We evaluated a 1–year period following the entry visit. We recorded if any LBP-related charges occurred beyond the entry visit and the duration of the LBP episode of care as the number of days from entry to the last LBP-related charge in the 1–year follow-up. We recorded the occurrence of the following utilization outcomes;(1) radiographs of lumbo-pelvic region,

(2) advanced imaging (MRI or computed tomography scan of lumbo-pelvic region,

(3) office visit with a spine surgeon (orthopedic or neurosurgeon) beyond the entry visit,

(4) surgical procedure (discectomy, laminectomy, fusion or rhizotomy of the lumbosacral region),

(5) fluoroscopically guided epidural injection of the lumbar spine or sacroiliac joint) and

(6) LBP-related emergency department visit beyond the entry visit.Costs were recorded from allowed costs for all claims associated with a LBP-related ICD-9 code during the year following the entry visit and summed to compute total LBPrelated health care costs. If health care utilization for LBP was identified in the EMR but not in claims data, we imputed the cost as the mean of available claims for the procedure.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed with settings comprising at least 5% of the sample (primary care, physiatry, chiropractic and physical therapy). We compared patient characteristics and co-morbidities between entry settings using chi square and Kruskal–Wallis tests. Episode of care duration and total LBP-related costs were described as medians or means with 95% confidence interval (CI), respectively. Because we did not randomly assign patients to entry settings, we employed inverse probability weighting using propensity score to control selection bias. [26] Propensity scores were estimated using a multinomial logit regression because the dependent variable was entry provider category with four groups: physical therapy, primary care, physical medicine and chiropractic. In this regression, covariates at baseline (age, gender, LBP primary diagnosis, CCI, smoking status, obesity, chronic pain co-morbidity, substance use disorder, mental health co-morbidity, prior spine surgery, medications and patients’ zip codes were controlled. The inverse probability weighting of each patient was used in the logistic regressions and generalized linear regressions. Utilization outcomes were compared using adjusted odds ratios with 95% CI from multivariate logistic regression. Generalized linear regressions with gamma distribution and log link function were used to examine duration of care and costs because of the positively skewed distributions. [27] A significance level of P < 0.05 was used.

Results

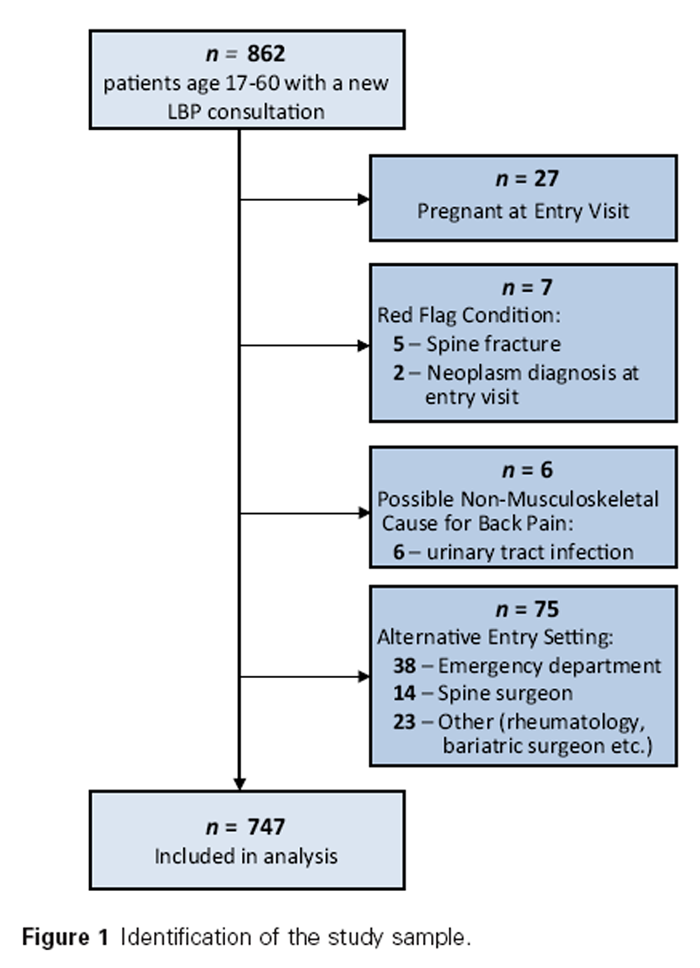

Figure 1

Table 1

Table 2

Table 3

Table 4 A total of 862 individuals had a new LBP consultation during the study dates, and 747 met all inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Entry visit setting was most commonly

primary care (n = 409, 54.8%) followed by

chiropractic (n = 207, 27.7%),

physiatry (n = 83, 11.1%) and

physical therapy (n = 48, 6.4%).Patient characteristics and co-morbidities by entry setting are outlined in Table 1. Likelihood that LBP was the primary diagnosis was lower in primary care or chiropractic compared with physical therapy or physiatry (P < 0.001). Patients entering in primary care were more likely to have co-morbid substance use disorders (P = 0.047), and those entering in primary care or physiatry were more likely to have chronic pain co-morbidity (P < 0.001).

Outcomes by entry visit setting are described in Table 2. Entry setting was predictive of outcomes in the weighted multivariate models (Table 3 & Table 4). Relative to entry in primary care, entry in physiatry was associated with increased risk for radiograph (OR = 3.46, P = 0.001), advanced imaging (OR = 3.38, P < 0.001), injections (OR = 4.91, P < 0.001), surgery (OR = 4.76, P = 0.012) and total LBP-related health care costs (standardized B = 0.67, P < 0.001). Entry in chiropractic was associated with decreased risk for advanced imaging (OR = 0.21, P = 0.001) or a surgeon visit (OR = 0.13, P = 0.005), and with increased episode of care duration (standardized B = 0.51, P < 0.001). Entry in physical therapy was associated with decreased risk of radiographs (OR = 0.39, P = 0.017) and no patient entering in physical therapy had surgery.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to describe the choices made by privately insured patients with LBP about where to begin seeking health care. As expected, we found a wide variety of settings were used for entry, but most common were primary care and chiropractic, with smaller percentages entering with a physiatrist or physical therapist. The percentages in our sample generally conform to national averages. [24] We found the entry setting to predict future health care utilization, costs and the LBP episode of care duration after controlling for patient demographic and co-morbidity variables. Relative to beginning in primary care, entry with a chiropractor or physical therapist was associated with reduced risk for imaging, injections, surgical consultation and surgery, while entry with a physiatrist increased risk for many of these outcomes and overall LBP-related health care costs.

Few studies have focused specifically on the choice of entry visit provider as a determinant of the future course of LBP care, but our findings support work that has been done suggesting the future course of care is dependent on the provider with whom a patient begins care. [24, 28] More specifically, existing studies suggest there may be reduced exposure to expensive and invasive procedures and lower costs when a non-doctor provider such as a physical therapist or chiropractor is the initial provider compared with patients beginning with a medical doctor. [29–31] In our sample, episodes beginning in chiropractic or physical therapy were less likely to involve imaging, surgeon visits or injections over the subsequent year relative to episodes beginning with a doctor, particularly physiatrists. Total LBP-related health care costs were predictably highest for the entry setting with greatest utilization of imaging and invasive procedures (physiatry) and trended lower for chiropractic and physical therapy, although only differences with physiatry reached statistical significance.

Several factors may explain these findings. Those seeking care from non-doctor providers for LBP tend to be younger and healthier. [32] In our sample, rates of co-morbidities and smoking were lower for patients beginning care in chiropractic or physical therapy. Although these factors were controlled in analyses, the potential impact of selection bias cannot be eliminated.

Differences in the training and scope of practice of the provider are likely another factor. Chiropractic and physical therapy provide manual therapy and exercise interventions consistent with their training, and these strategies are generally consistent with practice guidelines for new episodes of LBP. [33] A recent review found chiropractors and physical therapists are more likely to provide guideline-adherent care for LBP than primary care doctors. [34] Non-doctor providers are unable to order MRIs or prescribe opioids in contradiction to guidelines. Physical therapists in the United States are unable to order radiographs. Non-doctor providers also tend to see patients more frequently and for longer durations, providing greater opportunity for patient education. Time constraints and difficulty providing adequate education about activity are cited by primary care doctors as challenges for providing evidence-based care to patients with LBP. [35, 36] Greater alignment of the practice of non-doctor providers with evidence-based recommendations for LBP has led to suggestions that policy changes that encourage shifting initial care seeking for LBP towards greater use of non-doctor providers may be an effective in reducing costs and improve outcomes for LBP care [37, 38], as well as calls for greater efforts to provide consistent evidence-based information to health care professionals who manage patients with LBP regardless of discipline. [39]

The results of this study should be considered in light of important limitations. Potential confounding variables were not represented in our data including pain severity or duration of symptoms. The lack of these and other variables along with the unbalanced and small size of some of our groups limit the ability to control selection bias. Our sample was small and involved a single insurer in one geographic region. Patients in this study had insurance coverage to access doctor or non-doctor specialists for LBP without prior approval requirements. Although the generalizability of these findings may be limited, they should encourage more research on the influence of entry setting on the course of care for LBP and exploration of policies to facilitate more efficient and effective care for persons with LBP beginning with the first provider seen by a patient.

References:

Deyo, R. A., Mirza, S. K. & Martin, B. I. (2006)

Back pain prevalence and visit rates: estimates from U.S. national surveys, 2002.

Spine, 31 (23), 2724–2727.Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Ostelo R, et al.

Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Low Back Pain in Primary Care:

An International Comparison

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001 (Nov 15); 26 (22): 2504–2513Martin, BI, Deyo, RA, Mirza, SK et al.

Expenditures and Health Status Among Adults With Back and Neck Problems

JAMA 2008 (Feb 13); 299 (6): 656–664Davis MA, Onega T, Weeks WB, Lurie JD.

Where the United States Spends its Spine Dollars: Expenditures on Different Ambulatory Services

for the Management of Back and Neck Conditions

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012 (Sep 1); 37 (19): 1693–1701Hart, L. G., Deyo, R. A. & Cherkin, D. C. (1995)

Physician office visits for low back pain: frequency, clinical evaluation, and treatment patterns from a national survey.

Spine, 20 (1), 11–19.Licciardone, J. C. (2008)

The epidemiology and medical management of low back pain during ambulatory medical visits in the United States.

Osteopathic Medicine and Primary Care, 2, 11.St Sauver, J. L.,Warner, D. O., Yawn, B. P., et al. (2013)

Why patients visit their doctors: assessing the most prevalent conditions in a defined American population.

Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 88 (1), 56–67.Di Fabio, R. P. & Boissonault, W. (1998)

Physical therapy and healthrelated outcomes for patients with common orthopaedic diagnoses.

Journal of Orthopedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 27 (3), 219–230.Chevan, J. & Riddle, D. L. (2011)

Factors associated with care seeking from physicians, physical therapists or chiropractors by persons with spinal pain: a population-based study.

Journal of Orthopedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 41 (7), 467–476.Coulter, I. D., Hurwitz, E. L., Adams, A. H., Genovese, B. J., Hays, R. & Shekelle, P. G. (2002)

Patients Using Chiropractors in North America:

Who Are They, and Why Are They in Chiropractic Care?

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002 (Feb 1); 27 (3): 291–298Cherkin, D. C., Deyo, R. A., Wheeler, K. & Ciol, M. A. (1994)

Physician variation in diagnostic testing for low back pain. Who you see is what you get.

Arthritis & Rheumatism, 37 (1), 15–22.Deyo, R. A. & Mirza, S. K. (2006)

Trends and variations in the use of spine surgery.

Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research, 443 (2), 139–146.Friedly, J., Chan, L. & Deyo, R. (2008)

Geographic variation in epidural steroid injection use in Medicare patients.

Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery – American, 90 (8), 1730–1737.Webster, B. S., Cifuentes, M., Verma, S. & Pransky, G. (2009)

Geographic variation in opioid prescribing for acute, work-related, low back pain and associated factors: a multilevel analysis.

American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 52 (2), 162–171.Weinstein, J. N., Lurie, J. D., Olson, P. R., Bronner, K. K. & Fisher, E. S. (2006)

United States’ trends and regional variations in lumbar spine surgery: 1992–2003.

Spine, 31 (23), 2707–2714.Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Turner JA, Martin BI.

Overtreating Chronic Back Pain: Time to Back Off?

J Am Board Fam Med. 2009 (Jan); 22 (1): 62–68Freburger, J. K., Holmes, G. M., Agans, R. P., Jackman, A. M., Darter, J. D., Wallace, A. S., Castel, L. D., Kalsbeek, W. D. & Carey, T. S. (2009)

The rising prevalence of chronic low back pain.

Archives of Internal Medicine, 169 (3), 251–258.Mafi, J. N., McCarthy, E. P., Davis, R. B. & Landon, B. E. (2013)

Worsening Trends in the Management and Treatment of Back Pain

JAMA Internal Medicine 2013 (Sep 23); 173 (17): 1573–1581Fritz, J. M., Brennan, G. P., Hunter, S. J. & Magel, J. S. (2013)

Initial management decisions after a new consultation for low back pain: implications of the usage of physical therapy for subsequent health care costs and utilization.

Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 94 (5), 808–816.Graves, J. M., Fulton-Kehoe, D., Jarvik, J. G. & Franklin, G. M. (2012)

Early imaging for acute low back pain: one-year health and disability outcomes among Washington State workers.

Spine, 37 (18), 1617–1627.Webster, B. S., Bauer, A. Z., Choi, Y., Cifuentes, M. & Pransky, G. S. (2013)

Iatrogenic consequences of early MRI in acute work-related disabling low back pain.

Spine, 38 (22), 1939–1946.Webster, B. S. & Cifuentes, M. (2010)

Relationship of early magnetic resonance imaging for work-related acute low back pain with disability and medical utilization outcomes.

Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 52 (9), 900–907.Webster, B. S., Verma, S. K. & Gatchel, R. J. (2007)

Relationship between early opioid prescribing for acute occupational low back pain and disability duration, medical costs, subsequent surgery and late opioid use.

Spine, 32 (19), 2127–2132.Kosloff TM, Elton D, Shulman SA, et al.

Conservative Spine Care: Opportunities to Improve the Quality and Value of Care

Popul Health Manag. 2013 (Dec); 16 (6): 390–396Quan, H., Sundararajan, V., Halfon, P., Fong, A., Burnand, B., Luthi, J. C., Saunders, L. D., Beck, C. A., Feasby, T. E. & Ghali,W. A. (2005)

Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data.

Medical Care, 43 (11), 1130–1139.Spreeuwenberg, M. D., Bartak, A., Croon, M. A., Hagenaars, J. A., Busschbach, J. J., Andrea, H., Twisk, J. & Stijnen, T. (2010)

The multiple propensity score as control for bias in the comparison of more than two treatment arms: an introduction from a case study in mental health.

Medical Care, 48 (2), 166–174.Moran, J. L., Solomon, P. J., Peisach, A. R. & Martin, J. (2007)

New models for old questions: generalized linear models for cost prediction.

Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 13 (3), 381–389.Carey, T. S., Freburger, J. K., Holmes, G. M., Castel, L., Darter, J., Agans, R., Kalsbeek, W. & Jackman, A. (2009)

A long way to go: practice patterns and evidence in chronic low back pain care.

Spine, 34 (7), 718–724.Mitchell, J. M. & de Lissovoy, G. A. (1997)

A comparison of resource use and cost in direct access versus physician referral episodes of physical therapy.

Physical Therapy, 77 (1), 10–18.Ohja, H. A., Snyder, R. S. & Davenport, T. E. (2014)

Direct access compared with referred physical therapy episodes of care: a systematic review.

Physical Therapy, 94 (1), 14–30.Liliedahl RL, Finch MD, Axene DV, Goertz CM.

Cost of Care for Common Back Pain Conditions Initiated With Chiropractic

Doctor vs Medical Doctor/Doctor of Osteopathy as First Physician:

Experience of One Tennessee-Based General Health Insurer

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2010 (Nov); 33 (9): 640–643Hestbaek L, Munck A, Hartvigsen L, Jarbol DE, Sondergaard J, Kongsted A.

Low Back Pain in Primary Care: A Description of 1250 Patients

with Low Back Pain in Danish General and Chiropractic Practice

Int J Family Med. 2014 (Nov 4); 2014: 106102Chou R, Huffman LH; American Pain Society.

Nonpharmacologic Therapies for Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Review of the Evidence for an American Pain Society/

American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline

Annals of Internal Medicine 2007 (Oct 2); 147 (7): 492–504Amorin-Woods LG, Beck RW, Parkin-Smith GF, Lougheed J, Bremner AP.

Adherence to Clinical Practice Guidelines Among Three Primary

Contact Professions: A Best Evidence Synthesis of the Literature

for the Management of Acute and Subacute Low Back Pain

J Can Chiropr Assoc 2014 (Sept); 58(3): 220–237Breen, A., Austin, H., Campion-Smith, C., Carr, E. & Mann, E. (2007)

You feel so hopeless’: a qualitative study of GP management of acute back pain.

European Journal of Pain, 11 (1), 21–29.Corbett, M., Foster, N. & Ong, B. N. (2009)

GP attitudes and selfreported behaviour in primary care consultations for low back pain.

Family Practice, 26 (5), 359–364.Foster, N. E., Hartvigsen, J. & Croft, P. R. (2012)

Taking responsibility for the early assessment and treatment of patients with musculoskeletal pain: a review and critical analysis.

Arthritis Research and Therapy, 14 (1), 205.Hartvigsen, J., Foster, N. E. & Croft, P. R. (2011)

We need to rethink front line care for back pain.

British Medical Journal, 342, d3260.Cutforth, G., Peter, A. & Taenzer, P. (2011)

The Alberta Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Ambassador Program: the development of a contextually relevant, multidisciplinary clinical practice guideline for non-specific low back pain: a review.

Physiotherapy Canada, 63 (3), 278–286.

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return to WORKERS' COMPENSATION

Return to INITIAL PROVIDER/FIRST CONTACT

Since 8-10-2018

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |