An Assessment of Nonoperative Management Strategies

in a Herniated Lumbar Disc Population:

Successes Versus FailuresThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Global Spine J 2021 (Sep); 11 (7): 1054–1063 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Daniel T. Lilly, MD, Mark A. Davison, MD and Owoicho Adogwa, MD, MPH

Cleveland Clinic,

Cleveland, OH, USA.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Objective: To compare the utilization of conservative treatments in patients with lumbar intervertebral disc herniations who were successfully managed nonoperatively versus patients who failed conservative therapies and elected to undergo surgery (microdiscectomy).

Methods: Clinical records from adult patients with an initial herniated lumbar disc between 2007 and 2017 were selected from a large insurance database. Patients were divided into 2 cohorts: patients treated successfully with nonoperative therapies and patients that failed conservative management and opted for microdiscectomy surgery. Nonoperative treatments utilized by the 2 groups were collected over a 2-year surveillance window. "Utilization" was defined by cost billed to patients, prescriptions written, and number of units disbursed.

Results: A total of 277,941 patients with lumbar intervertebral disc herniations were included. Of these, 269,713 (97.0%) were successfully managed with nonoperative treatments, while 8,228 (3.0%) failed maximal nonoperative therapy (MNT) and underwent a lumbar microdiscectomy. MNT failures occurred more frequently in males (3.7%), and patients with a history of lumbar epidural steroid injections (4.5%) or preoperative opioid use (3.6%). In a logistic multivariate regression analysis, male sex and utilization of opioids were independent predictors of conservative management failure. Furthermore, a cost analysis indicated that patients who failed nonoperative treatments billed for nearly double ($1718/patient) compared to patients who were successfully treated ($906/patient).

Conclusion: Our results suggest that the majority of patients are successfully managed nonoperatively. However, in the subset of patients that fail conservative management, male sex and prior opioid use appear to be independent predictors of treatment failure.

Keywords: disc; disc herniation; discectomy; low back pain; lumbar.

From the Full-Text Article:

Introduction

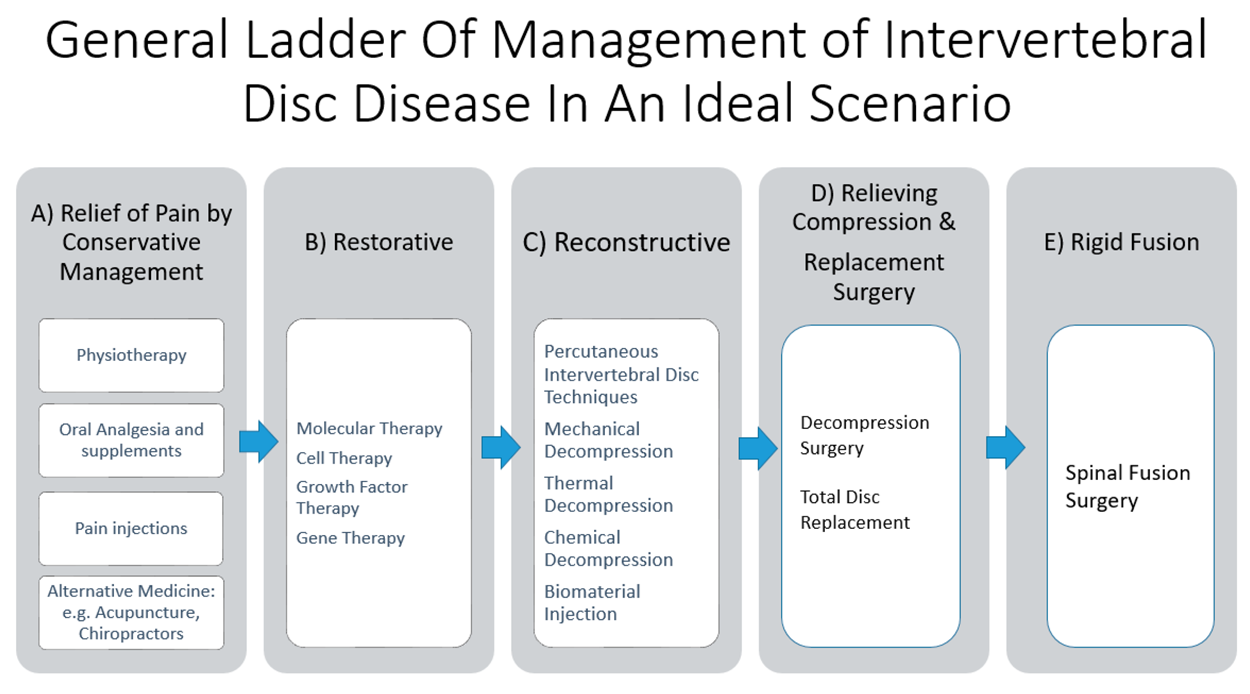

Low back pain is thought to affect more than 80% of people at some point during their lifetime making it one of the most prevalent medical conditions worldwide. [1, 2] Morbidity from lumbar spine disease consistently accounts for the greatest source of years lived with disability in the United States and, as such, places a substantial burden on both patients and the workforce. [3, 4] Expenditures associated with treating low back pain are estimated to be greater than $100 billion annually and have been demonstrated to be increasing faster than overall US health care costs. [5] Intervertebral disc disorders are a common cause of low back pain, with a herniated disc affecting an estimated 2% to 3% of the population at any given time. [5–7] Use of first-line conservative management strategies such as analgesic medications, steroid injections, and physical therapy usually results in symptomatic relief in over 90% of patients within 12 weeks of symptom onset. [7–10] While conservative management is often successful, the effectiveness and costs of prolonged use of maximal nonoperative therapy (MNT) in patients demonstrating no early clinical improvement is unclear. [8, 11–13]

To this end, the aim of this study was to compare the utilization of conservative treatments in patients with a lumbar intervertebral disc herniation who were successfully managed nonoperatively versus patients who failed conservative therapies and elected to undergo surgery.

Methods

Data Source

The population was obtained from the Humana Ortho (HORTHO) insurance database, which includes over 20.9 million patient lives and encompasses both private/commercially insured and Medicare Advantage beneficiaries with orthopedic diagnoses. Patient records were accessed through a remote computer server maintained by PearlDiver (PearlDiver Technologies, Inc, Colorado Springs, CO). Clinical documents were queried using Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes, International Classification of Diseases (ICD) diagnosis and procedure codes, and generic drug codes specific to Humana.

Patient Sample

The base population consisted of adult patients (≥19 years old) with a primary diagnosis of lumbar disc herniation. Patients were subsequently divided into 2 cohorts—a successful conservative therapy cohort and a cohort that failed nonoperative management and opted for surgery. The failed nonoperative treatment population was composed of patients who underwent a primary ≤3–level lumbar microdiscectomy procedure from 2007 to 2017. Only patients continuously active within the insurance system for at least 2 years prior to their microdiscectomy operation were included.

The successful nonoperative therapy cohort consisted of patients from the base population who did not undergo microdiscectomy surgery and were continuously active within the insurance system for at least 2 years following their primary lumbar disc herniation diagnosis.

Patients were excluded if they had a previous cervical or lumbar fusion surgery, or had a diagnosis of lumbosacral spinal fracture or malignancy. Both ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes were incorporated for each respective selection/exclusion diagnostic criteria, while CPT codes were utilized for the aforementioned procedures (Appendix A).

Medical Therapies

The use of conservative therapies within the 2 years prior to microdiscectomy surgery in the “failed” treatment group and within 2 years following diagnosis in the “successful” conservative management cohort was documented. Nonoperative treatments included nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioid medications, muscle relaxants, lumbar epidural steroid injections (LESIs), physical therapy and occupational therapy sessions (PT/OT), and chiropractor treatments. Regarding prescription opioids, only oxycodone hydrochloride, hydrocodone/acetaminophen, and oxycodone/acetaminophen, the most commonly utilized formulations (prescribed in >80% of patients) were queried. Emergency department (ED) visits for which a lumbar disc herniation was recorded as the primary complaint were also collected. All imaging studies involving the lumbar spine including X-rays, computed tomography scans, and magnetic resonance imaging studies were captured. Generic drug codes and CPT codes were used to query medication and procedures use, respectively (Appendix B).

Nonoperative therapy utilization was characterized by average dollars spent ($US per patient), average number of documented prescriptions, and average number of units billed for. A “unit” consists of an individual pill, injection, therapy visit, ED visit, or imaging study. In addition to the averages, the utilization of each conservative treatment was normalized by the number of unique patients utilizing the respective therapy. The term “cost” represents the actual amount paid by insurers.

Baseline Demographics and Comorbidities

Patient demographic information including age, gender, geographical region, and ethnicity was collected. Patient age information was inherently binned into 5–year intervals as a privacy measure. Geographical region associations were to 1 of 4 distinct territories (Midwest, Northeast, South, and West), which are consistent with US Census Bureau guidelines and were derived from the location in which the insurance claim was filed. Additionally, ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes were used to collect common patient comorbidities including obesity (body mass index ≥30 kg/m2), type 2 diabetes mellitus, smoking status, atrial fibrillation, history of myocardial infarction, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Appendix C).

Data Analysis

The primary objective was to compare the nonoperative treatment utilization in the cohort successfully managed with conservative treatments with the patients that failed medical management and elected to undergo microdiscectomy surgery. Comparisons between categorical parameters were made using χ2 tests, with P values <.05 considered statistically significant findings. Independent predictors of conservative management failure were determined through a multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusting for patient age (reference: 50–54 years), gender (reference: Females), race (reference: Caucasian), geographic region (reference: Midwest), obesity, diabetes, smoking history, and opioid utilization. All statistical calculations were carried out in R (The R Project for Statistical Computing) within the PearlDiver platform.

Results

Patient Population

Table 1

(page 3)A total of 277,941 adult patients diagnosed with a lumbar herniated intervertebral disc comprised the base population. Demographically, there was a greater proportion of females (56.6%) and patients identifying as White (70.8%), Table 1. Geographically, the majority of patients resided in the Southern region (66.0%) followed by the Midwest region (22.2%), Table 1. The most prevalent comorbidities within the base population included diabetes (35.0%), obesity (25.5%), and smoking (16.3%), Table 1.

Failure Rate Comparison

There were 269,713 patients (97.0%) treated successfully with nonoperative management alone, while 8,228 patients (3.0%) ultimately failed conservative measures and elected to have surgery, Table 1. High nonoperative therapy failure rates were observed in males (3.7%) and patients from the Midwest region (3.4%), Table 1. Similarly, smokers (3.4%) and patients with a history of myocardial infarction (3.1%) also had high nonoperative therapy failure rates, Table 1.

Table 2

Table 3

(page 5)

Table 4

(page 6)

Table 5

(page 6)When assessing nonoperative management failure rates at the individual treatment level, patients utilizing muscle relaxants (4.0%), LESIs (4.5%), and those presenting to the ED for back pain or radiculopathy (21.5%) were associated with the highest conservative therapy failure rates. In fact, the utilization of each of the tracked therapies conferred a greater risk of treatment failure versus the average population failure rate (3.0%), Table 1. Looking at the age distribution, a greater percentage of patients from the surgery cohort (20.4%) were <50 years compared to the successful nonoperative management population (13.8%), Table 2.

Nonoperative Therapy Utilization

Comparing the costs associated with conservative therapies during the 2–year surveillance window, patients who failed nonoperative management billed for nearly double ($1,718/patient) compared to patients who were successfully treated ($906/patient), Table 3. In the failed nonoperative management cohort, the greatest contributors to total costs included lumbar spine imaging (44.7%), and LESIs (35.5%), with opioid medications comprising 5.1%, Table 3.

When normalized by patient utilizing each respective therapy, the failed conservative management cohort spent more on LESIs (failed cohort: $1,222.89/patient; successful cohort: $1,040.73/patient), lumbar spine imaging (failed cohort: $777.26/patient; successful cohort: $384.77/patient), and ED visits (failed cohort: $756.93/patient; successful cohort: $522.79/patient), Table 4.

Predictors of Failed Nonoperative Therapy

In our multivariate regression analysis, male gender (odds ratio [OR]: 1.49 495% confidence interval [CI]: 1.428–1.564) and opioid utilization during the conservative therapy trial (OR: 2.72 395% CI: 2.526–2.939) were independent predictors of nonoperative treatment failure, Table 5. Compared to patients aged 50 to 54, individuals in the age bracket 70 to 74 (OR: 2.24 595% CI: 2.021–2.497) were the most likely age group to fail conservative management, Table 5. On a geographic basis, patients from the South (OR: 0.88 095% CI: 0.834–0.928) or West (OR: 0.88 695% CI: 0.813–0.965) were less likely to fail nonoperative therapies than patients from the Midwest.

Discussion

Herniated intervertebral disc disorders are a primary contributor to low back pain, and have inflicted a considerable cost to our society. While early conservative management strategies have been effective in most patients, the role for long-term utilization of these therapies is unclear. Therefore, we sought to compare the nonoperative therapy utilization in herniated lumbar disc patients successfully managed with nonoperative therapy with those who failed conservative management and opted for microdiscectomy.

In this retrospective study of 277,941 adult patients diagnosed with a herniated lumbar disc, we found that 97.0% were successfully managed nonoperatively, while 3.0% failed MNT and underwent a microdiscectomy procedure. A multivariate regression analysis determined that male gender and opioid utilization during the nonoperative therapy trial were independent predictors of conservative management failure in our cohort. Additionally, a cost analysis indicated that patients who failed nonoperative treatments billed for nearly twice as much compared to patients who were successfully treated (failed cohort: $1,718/patient; successful cohort: $906/patient).

Our findings are consistent with other studies describing the selection and costs of conservative therapies utilized in the management of this pathology. In a prospective observational study of 1,417 patients, Cummins et al assessed the nonoperative medical resources used by patients with degenerative lumbar spine pathologies. Within the cohort diagnosed with a herniated disc (743 patients), greater than 40% had trialed physical therapy, anti-inflammatory medications, opioids, injections, and had been seen by a chiropractor. Moreover, the authors found that patients with a herniated disc were significantly more likely to visit the emergency department, utilize opioids, muscle relaxants, or antidepressants than patients with any other lumbar spine disorder analyzed. [14]

Due to the considerable costs associated with prolonged conservative therapy utilization, determining predictors of nonoperative treatment failure in patients with an intervertebral disc herniation is of significant interest. In a systematic review of 14 studies, Verwoerd et al found evidence that higher baseline leg pain serves as a predictor of surgical management in patients with sciatica. Among other variables analyzed, the results demonstrated no association between age, gender, body mass index, or smoking status with nonoperative treatment prognosis. However, the authors determined that the current body of evidence is clinically, methodologically, and statistically heterogeneous, limiting the ability to identify potential prognostic factors in nonsurgically treated sciatica [15] In our current study of over a 250,000 patients with symptomatic disc herniations, we identified male gender and chronic opioid use as independent predictors of failing nonoperative management and undergoing a microdiscectomy procedure.

While the subset of patients with intervertebral disc herniation who failed medical management in our cohort is low (3.0%), it is important to recognize that the consequences of prolonged trials of MNT are not trivial. A common methodology used to evaluate the value of different treatment modalities is the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). [16–18] This ratio is defined as the cost difference between 2 therapies divided by the difference in their efficacy, thus facilitating comparisons between 2 potential interventions on the basis of cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained. [16] The comparative value of surgical versus long-term nonoperative treatment for a herniated disc has been previously examined. In a 4–year cost-effectiveness analysis comparing surgery to conservative treatment of degenerative lumbar spine conditions, Tosteson et al found that the ICER for discectomy surgery to repair a herniated disc was $20,600/QALY gained relative to nonoperative management over the 4–year period. [17] This is well below the upper limit for high-value interventions in the United States, typically set at $50,000/QALY. [19, 20]

Conversely, the comparative effectiveness of different nonoperative therapies versus each other, or to placebo, remains unclear based on a lack of high-quality studies. However, evidence suggests that extended courses of MNT in patients with a herniated disc who do not demonstrate early improvement may be of little value. In a cohort of patients with a lumbar herniated disc who remained symptomatic after 6 weeks of conservative treatment, Parker et al found that continuation of medical management for 2 additional years did not lead to a minimally clinically important difference in any outcome including Numeric Rating Scales for leg or back pain, Oswestry Disability Index, Short Form 12–item physical or mental health surveys, or Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale. The 2–year costs of treatment (direct costs) plus costs due to missed work (indirect costs) averaged $7,097 per patient in the herniated disc cohort. [11] Considering the minimal improvement in these patients, this indicates a high ICER for prolonged MNT. Analogous to the aforementioned studies, we found almost a 2–fold costs difference between use of conservative therapies in patients who eventually underwent surgery compared to patients successfully treated nonoperatively. As these surgical patients likely experienced a limited treatment effect from conservative care, this provides further evidence that the ICER for prolonged MNT may be high. Identifying surgical candidates earlier in the treatment process is a potential source of cost-savings and is therefore of interest to both payers and providers.

Limitations

The results and implications of this analysis must be interpreted within the setting of its limitations. The insurance database used to assemble the study population for this investigation is composed solely of Medicare Advantage beneficiaries as well as private/commercially insured patients. Medicaid patients were therefore not captured in our study. Only services billed to an insurance provider were included in our analysis; hence, the utilization metrics reported are likely an underestimate, as over-the-counter medications and therapies omitted from insurance coverage were not included in our study. Additionally, while data within large patient registries is free from many biases inherent to studies where data is collected by the investigators, there have been reports suggesting that errors may exist in these types of databases. [21–23]

Most important, the robust insurance database utilized in this investigation lacks clinical context and individual diagnostic information. This has the potential to affect our results, as it is possible that patients who failed nonoperative management and underwent a microdiscectomy may have had more severe baseline symptoms. It is also likely that our cohorts were biased by patients who were poor surgical candidates and not offered operative management. Specifically, the regression analysis suggests that patients with comorbid obesity or diabetes were more likely to be treated successfully with nonoperative management strategies, when the lumbar spine literature indicates the contrary. [24, 25] The more likely explanation behind this observation is the fact that patients with these comorbidities are more prone to infections and less likely to benefit from operative management, and were therefore less likely to be offered surgery in the first place.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, our retrospective study comprising over 270,000 patients identified substantial differences in the utilization patterns and associated costs of nonoperative therapies trialed by patients with a lumbar herniated disc who were successfully treated conservatively versus those who failed nonoperative care and underwent a microdiscectomy surgery.

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest the majority of patients diagnosed with a herniated lumbar disc are successfully managed nonoperatively. However, in the subset of patients that fail conservative management, male gender and prior opioid use are independent predictors of treatment failure.

Additional files

References:

Freburger JK, Holmes GM, Agans RP, et al.

The rising prevalence of chronic low back pain.

Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:251–258Thiese MS, Hegmann KT, Wood EM, et al.

Prevalence of low back pain by anatomic location

and intensity in an occupational population.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:283Murray CJ, Atkinson C, Bhalla K, et al.

The State of US Health, 1990-2010:

Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors

JAMA 2013 (Aug 14); 310 (6): 591–608Shmagel A, Foley R, Ibrahim H.

Epidemiology of chronic low back pain in US adults: data from the

2009-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68:1688–1694Martin, BI, Deyo, RA, Mirza, SK et al.

Expenditures and Health Status Among Adults

With Back and Neck Problems

JAMA 2008 (Feb 13); 299 (6): 656–664Vialle LR, Vialle EN, Suarez Henao JE, Giraldo G.

Lumbar disc herniation.

Rev Bras Ortop. 2010;45:17–22Amin RM, Andrade NS, Neuman BJ.

Lumbar disc herniation.

Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2017;10:507–516Alentado VJ, Lubelski D, Steinmetz MP, Benzel EC, Mroz TE.

Optimal duration of conservative management prior to surgery for

cervical and lumbar radiculopathy: a literature review.

Global Spine J. 2014;4:279–286Gugliotta M, da Costa BR, Dabis E, et al.

Surgical versus conservative treatment for lumbar

disc herniation: a prospective cohort study.

BMJ Open. 2016;6:e012938Shamim MS, Parekh MA, Bari ME, Enam SA, Khursheed F.

Microdiscectomy for lumbosacral disc herniation

and frequency of failed disc surgery.

World Neurosurg. 2010;74:611–616Parker SL, Godil SS, Mendenhall SK, Zuckerman SL, Shau DN, McGirt MJ.

Two-year comprehensive medical management of degenerative lumbar spine

disease (lumbar spondylolisthesis, stenosis, or disc herniation):

a value analysis of cost, pain, disability, and

quality of life: clinical article.

J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;21:143–149Tosteson AN, Skinner JS, Tosteson TD, et al.

The cost effectiveness of surgical versus nonoperative treatment for

lumbar disc herniation over two years: evidence from the

Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT).

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33:2108–2115Daffner SD, Hymanson HJ, Wang JC.

Cost and Use of Conservative Management of Lumbar

Disc Herniation Before Surgical Discectomy

Spine J. 2010 (Jun); 10 (6): 463–468Cummins J, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al.

Descriptive epidemiology and prior healthcare utilization of patients

in the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial’s (SPORT) three

observational cohorts: disc herniation, spinal stenosis,

and degenerative spondylolisthesis.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:806–814Verwoerd AJ, Luijsterburg PA, Lin CW, Jacobs WC, Koes BW, Verhagen AP.

Systematic review of prognostic factors predicting outcome

in non-surgically treated patients with sciatica.

Eur J Pain. 2013;17:1126–1137Cohen DJ, Reynolds MR.

Interpreting the results of cost-effectiveness studies.

J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:2119–2126Tosteson AN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, et al.

Comparative effectiveness evidence from the spine patient outcomes

research trial: surgical versus nonoperative care for spinal stenosis,

degenerative spondylolisthesis, and intervertebral disc herniation.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36:2061–2068Adogwa O, Davison MA, Vuong VD, et al.

Long term costs of maximum non-operative treatments in patients with

symptomatic lumbar stenosis or spondylolisthesis that

ultimately required surgery: a five-year cost analysis.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2019;44:424–430Neumann PJ, Cohen JT, Weinstein MC.

Updating cost-effectiveness—the curious resilience

of the $50,000-per-QALY threshold.

N Engl J Med. 2014;371:796–797Cameron D, Ubels J, Norstrom F.

On what basis are medical cost-effectiveness thresholds set?

Clashing opinions and an absence of data: a systematic review.

Glob Health Action. 2018;11:1447828Basques BA, McLynn RP, Fice MP, et al.

Results of database studies in spine surgery can

be influenced by missing data.

Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475:2893–2904Golinvaux NS, Bohl DD, Basques BA, Fu MC, Gardner EC, Grauer JN.

Limitations of administrative databases in spine research:

a study in obesity.

Spine J. 2014;14:2923–2928Faciszewski T, Broste SK, Fardon D.

Quality of data regarding diagnoses of spinal disorders

in administrative databases. A multicenter study.

J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:1481–1488Rihn JA, Radcliff K, Hilibrand AS, et al.

Does obesity affect outcomes of treatment for lumbar stenosis and

degenerative spondylolisthesis? Analysis of the

Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT).

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012;37:1933–1946Jackson KL, 2nd, Devine JG.

The effects of obesity on spine surgery:

a systematic review of the literature.

Global Spine J. 2016;6:394–400.

Return NON-PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Return to DISC HERNIATION & CHIROPRACTIC

Since 3-01-2023

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |