Health-related Quality of Life Among United States Service

Members with Low Back Pain Receiving Usual Care plus

Chiropractic Care plus Usual Care vs Usual Care Alone:

Secondary Outcomes of a Pragmatic Clinical TrialThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Pain Medicine 2022 (Aug 31); 23 (9): 1550–1559 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Ron D Hays, PhD, Zacariah K Shannon, DC, MS, Cynthia R Long, PhD, Karen L Spritzer, Robert D Vining, DC, DHSc, Ian Coulter, PhD, Katherine A Pohlman, DC, MS, PhD, Joan Walter, PA, JD, Christine M Goertz, DC, PhD

UCLA Department of Medicine,

Los Angeles, CA.

Department of Epidemiology,

University of Iowa,

Iowa City, IA.

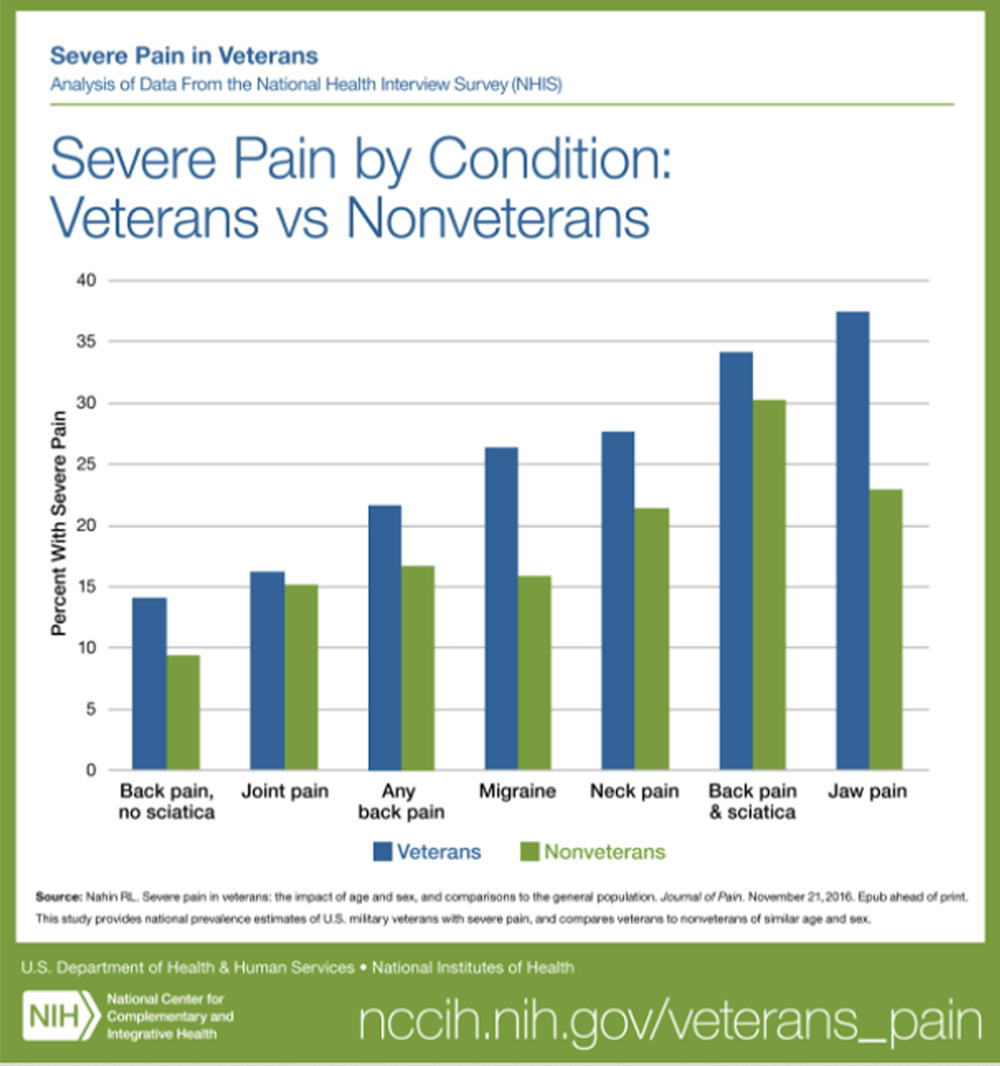

FROM: Nahin ~ Pain 2017Objective: This study examines Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS®)-29 v1.0 outcomes of chiropractic care in a multi-site, pragmatic clinical trial and compares the PROMIS measures to: 1) worst pain intensity from a numerical pain rating 0-10 scale, 2) 24-item Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ); and 3) global improvement (modified visual analog scale).

Design: A pragmatic, prospective, multisite, parallel-group comparative effectiveness clinical trial comparing usual medical care (UMC) with UMC plus chiropractic care (UMC+CC).

Setting: 3 military treatment facilities.

Subjects: 750 active-duty military personnel with low back pain.

Methods: Linear mixed effects regression models estimated the treatment group differences. Coefficient of repeatability to estimate significant individual change.

Results: We found statistically significant mean group differences favoring UMC+CC for all PROMIS®-29 scales and the RMDQ score. Area under the curve estimates for global improvement for the PROMIS®-29 scales and the RMDQ, ranged from 0.79 to 0.83.

Conclusions: Findings from this pre-planned secondary analysis demonstrate that chiropractic care impacts health-related quality of life beyond pain and pain-related disability. Further, comparable findings were found between the 24-item RMDQ and the PROMIS®-29 v1.0 briefer scales.

Keywords: PROMIS®; chiropractic care; clinical trial; health-related quality of life; low back pain; military; patient outcome assessment; usual medical care.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is the primary cause of years lived with disability worldwide for the past 3 decades across 126 of 195 countries. [1] The cost of LBP and other musculoskeletal pain conditions is increasing at a greater rate than other highly prevalent conditions. [2] As a result, back and neck pain currently account for the highest healthcare expenditures in the United States (U.S.), estimated at $134.5 billion in 2016. [2] The public health implications of LBP are exacerbated by our struggle to find safe and effective treatment options. The current literature shows that commonly used therapies, ranging from opioids [3] to spinal fusions, can lead to serious side effects with little impact on the pain experience. [4] In response, LBP guidelines increasingly recommend conservative therapies [5, 6] including spinal manipulation. [6–8]

More than half of U.S. adults have received care from a chiropractor. [9] The chiropractic therapeutic approach for LBP includes evaluation, management, and treatment with conservative care options like spinal manipulation, exercise, and lifestyle advice. [10] Meta-analyses have shown that spinal manipulation is effective for acute [11] and chronic LBP. [12]

The impact of chiropractic care on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of patients in military health systems in the U.S. is unknown. [13, 14] The military population is known to have high rates of LBP [15, 16], a threat to the military’s goal of maintaining combat readiness. [17] LBP is associated with poorer mental health and overall quality of life in military service members. [15]

There is a need to better understand the relationship of LBP with HRQOL outcomes among military service members. [15] Clinical studies evaluating treatment approaches for LBP have traditionally used measures of pain (89%) and disability (64%) more than other aspects of HRQOL (24%). [18] This narrow focus potentially misses important aspects of HRQOL for patients with LBP, including those seeking chiropractic care. [19]

The Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) includes measures of physical, mental, and social health. [20] Observational studies have included PROMIS® outcomes of chiropractic care. [21, 22] However, the validity of these studies is limited by inadequate comparison groups and residual confounding. PROMIS® measures remain unreported in clinical trials assessing chiropractic care.

To address this gap, a recent pragmatic, clinical trial of 750 active-duty military personnel designed to compare usual medical care (UMC) to UMC plus chiropractic care (UMC+CC) [13, 14] administered 2 “legacy” measures: the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) [23] and a numeric worse pain intensity item. In addition, the PROMIS®-29 v1.0 profile measure [20] was administered. We report pre planned secondary PROMIS®-29 v1.0 outcomes of this pragmatic clinical trial and compare these to the legacy measures.

Discussion

Goertz et al. [14] reported chiropractic care imparted beneficial effects on disability, average LBP in the past week, worst LBP in the past 24 hours, and bothersomeness of LBP symptoms. The current study extends this work by showing positive impacts of chiropractic care on all aspects of HRQOL measured in this study (including physical function, pain interference, sleep disturbance, anxiety, depression, and satisfaction with social role). The largest effects were for pain (PROMIS® pain interference, worst pain intensity in the past 24 hours, PROMIS® pain composite, and PROMIS® pain intensity item). While the positive effects of UMC+CC were statistically significant for the mental health measures, the differences between UMC and UMC+CC were small (e.g., at 12 weeks post-baseline depression and anxiety scale scores differed by about 1 T-score point), below the minimally important difference estimated for similar PROMIS measures. [27]

Previous studies have also reported beneficial effects of chiropractic care on HRQOL. An observational study of 2024 patients with chronic LBP or neck pain receiving care from 125 chiropractic clinics throughout the U.S. found significant group-level change over 3 months on all PROMIS®-29 v2.0 scores except for emotional distress, but the average change was small in magnitude, with effect sizes ranging from 0.08 for physical function to 0.20 for pain. [21] The United Kingdom back pain, exercise, and manipulation study documented similar (though slightly larger) improvements over 3 months attributable to manipulation of 2.5 and 2.9 points on the Short-form Health Survey (SF-36) physical and mental health summary scores, respectively. [28]

The current study also estimates the percentage of individuals improving on each aspect of HRQOL. The smallest percentage of improvement among those receiving UMC+CC was observed for sleep disturbance (17%) and the largest percentage was on pain interference (53%) at 6 weeks; at 12 weeks the smallest percentage improvement was 21% (depression) and the largest percentage improvement was 58% (pain interference). In comparison, the observational study noted above documented that from 13% (PROMIS®-29 v2.0 physical function) to 30% (PROMIS®-29 v2.0 mental health summary score) of the sample improved from baseline to 3 months later. [21] It is possible that chiropractic directly affects physical health and that the smaller changes in mental health measures such as depression and anxiety represent indirect effects. Future research should consider causal mediation analysis to shed light on this possibility.

We found substantial associations between change in the legacy RMDQ measure and change in the PROMIS®-29 physical function, pain interference, and pain intensity scales. AUCs using significant individual change in the RMDQ from baseline to 6-weeks later ranged from 0.82 to 0.85 for the worst pain in the last 24 hours item, and the PROMIS®-29 pain intensity item, pain interference scale, and physical function scale. AUCs with respect to a global improvement in LBP for the RMDQ and PROMIS®-29 v1.0 scales and ranged from 0.79 to 0.83. This is important because the RMDQ has 24 items and the longest PROMIS®-29 v1.0 scale is 4 items, while both the global improvement and PROMIS®-29 v1.0 pain intensity measure are only a single item.

The limitations of the clinical trial have been addressed in detail elsewhere. [14] Limitations include issues of heterogeneity inherent in all LBP research, difficulty in masking participants to group allocation, and a short length of follow-up. In addition, it is uncertain how long the positive effects of chiropractic persist beyond the 12 weeks of follow-up used in this study.

Further, the study findings are based on a sample of relatively young and mostly white military personnel treated in multidisciplinary care facilities. The integrated care setting may influence results by improving care coordination between chiropractors and medical providers. These findings should be replicated in non-military samples and with older adults in other settings of care.

Conclusion

Pre-planned secondary outcomes from this rigorous, pragmatic RCT demonstrate that chiropractic care can positively impact HRQOL beyond pain and pain-related disability. This along with prior research suggests positive effects of chiropractic care on patient-reported outcomes up to 3 months. Further, PROMIS® measures of pain and pain-related disability (5 items) performed similarly to the 24-item RMDQ in the evaluation of outcomes for patients under chiropractic care. The use of PROMIS® measures encompassing physical, mental, and social health provided a richer, more holistic picture of response to chiropractic care, with less time commitment for trial participants demonstrating benefit for outcomes assessment in research and clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the active-duty U.S. military personnel with low back pain who participated in this study.

References:

GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators.

Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with

disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories,

1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017.

Lancet Lond Engl. 2018 Nov 10;392(10159):1789–858.Dieleman JL, Cao J, Chapin A, et al.

US Health Care Spending by Payer and Health Condition, 1996-2016

JAMA 2020 (Mar 3); 323 (9): 863–884Krebs EE, Gravely A, Nugent S, Jensen AC, DeRonne B, Goldsmith ES, et al.

Effect of Opioid vs Nonopioid Medications on Pain-Related Function

in Patients With Chronic Back Pain or Hip or Knee Osteoarthritis Pain:

The SPACE Randomized Clinical Trial.

JAMA. 2018 Mar 6;319(9):872–82.Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al.

Systemic Pharmacologic Therapies for Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review

for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 480–492Oliveira CB, Maher CG, Pinto RZ, Traeger AC, Lin C-WC, Chenot J-F, et al.

Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain

in primary care: an updated overview.

Eur Spine J Off Publ Eur Spine Soc Eur Spinal Deform Soc Eur Sect Cerv Spine Res Soc. 2018;27(11):2791–803.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA;

Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 514–530Beliveau PJH, Wong JJ, Sutton DA, Simon NB, Bussieres AE, Mior SA, et al.

The Chiropractic Profession: A Scoping Review of Utilization Rates,

Reasons for Seeking Care, Patient Profiles, and Care Provided

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2017 (Nov 22); 25: 35Skelly AC, Chou R, Dettori JR, Turner JA, Friedly JL, et al.

Noninvasive Nonpharmacological Treatment for Chronic Pain:

A Systematic Review Update

Comparative Effectiveness Review Number 227

Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2020)Gallup, Inc. (2015)

Americans’ Perceptions of Chiropractic

Gallup-Palmer College of Chiropractic Inaugural ReportVining RD, Shannon ZK, Salsbury SA, Corber L, Minkalis AL, Goertz CM.

Development of a Clinical Decision Aid for Chiropractic Management

of Common Conditions Causing Low Back Pain in Veterans:

Results of a Consensus Process

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019 (Nov); 42 (9): 677–693Paige NM, Myiake-Lye IM, Booth MS, et al.

Association of Spinal Manipulative Therapy with Clinical Benefit and Harm

for Acute Low Back Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

JAMA. 2017 (Apr 11); 317 (14): 1451–1460Rubinstein SM, de Zoete A, van Middelkoop M, et al.

Benefits and Harms of Spinal Manipulative Therapy for the Treatment

of Chronic Low Back Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

of Randomised Controlled Trials

British Medical Journal 2019 (Mar 13); 364: l689Christine M. Goertz, Cynthia R. Long, Robert D. Vining, Katherine A. Pohlman,

Bridget Kane, Lance Corber, Joan Walter, and Ian Coulter

Assessment of Chiropractic Treatment for Active Duty, U.S. Military Personnel

with Low Back Pain: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial

Trials. 2016 (Feb 9); 17 (1): 70Goertz CM, Long CR, Vining RD, Pohlman KA, Walter J, Coulter I.

Effect of Usual Medical Care Plus Chiropractic Care vs Usual Medical Care

Alone on Pain and Disability Among US Service Members With

Low Back Pain. A Comparative Effectiveness Clinical Trial

JAMA Network Open. 2018 (May 18); 1 (1): e180105 NCT01692275Watrous JR, McCabe CT, Jones G, Farrokhi S, Mazzone B, Clouser MC, et al.

Low back pain, mental health symptoms, and quality of life

among injured service members.

Health Psychol. 2020 Jul;39(7):549–57.Kelley AM, MacDonnell J, Grigley D, Campbell J, Gaydos SJ.

Reported Back Pain in Army Aircrew in Relation to Airframe,

Gender, Age, and Experience.

Aerosp Med Hum Perform. 2017 Feb 1;88(2):96–103.Koreerat NR, Koreerat CM.

Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Injuries in a Security Force Assistance

Brigade Before, During, and After Deployment.

Mil Med. 2021 Jan 25;186(Suppl 1):704–8.Gianola S, Frigerio P, Agostini M, Bolotta R, Castellini G, Corbetta D, et al.

Completeness of Outcomes Description Reported in Low Back Pain

Rehabilitation Interventions: A Survey of 185 Randomized Trials.

Physiother Can. 2016;68(3):267–74.Deyo RA, Andersson G, Bombardier C, Cherkin DC, Keller RB, Lee CK, et al.

Outcome measures for studying patients with low back pain.

Spine. 1994;19(18 Suppl):2032S-2036S.Cella D, Choi SW, Condon DM, Schalet B, Hays RD, Rothrock NE, et al.

PROMIS® Adult Health Profiles: Efficient Short-Form Measures

of Seven Health Domains.

Value Health. 2019 May;22(5):537–44.Hays RD, Spritzer KL, Sherbourne CD, Ryan GW, Coulter ID.

Group and Individual-level Change on Health-related Quality of Life

in Chiropractic Patients With Chronic Low Back or Neck Pain.

Spine. 2019 May 1;44(9):647–51.Papuga MO, Barnes AL.

Correlation of PROMIS CAT instruments with Oswestry Disability Index

in chiropractic patients.

Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018 May 1;31:85–90.Roland M, Morris R.

A study of the natural history of back pain. Part I:

development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain.

Spine. 1983 Mar;8(2):141–4.Hays RD, Spritzer KL, Schalet BD, Cella D.

PROMIS®-29 v2.0 profile physical and mental health summary scores.

Qual Life Res. 2018 Jul;27(7):1885–91.Jacobson NS, Truax P.

Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining

meaningful change in psychotherapy research.

J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991 Feb;59(1):12–9.Hays RD, Slaughter ME, Spritzer KL, Herman PM.

Estimating responders to treatment using five indices of

significant individual change.

JMPT submitted for publication.Lee AC, Driban JB, Price LL, Harvey WF, Rodday AM, Wang C.

Responsiveness and minimally Important differences for 4

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

Short Forms: Physical function, Pain interference,

depression, and anxiety in knee osteoarthritis.

J Pain. 2017 Sep;18(9):1096-1110. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2017.05.001.Underwood M, UK BEAM Trial Team.

United Kingdom Back Pain Exercise and Manipulation (UK BEAM) Randomized Trial:

Effectiveness of Physical Treatments for Back Pain in Primary Care

British Medical Journal 2004 (Dec 11); 329 (7479): 1377–1384

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return to OUTCOME ASSESSMENT

Return NON-PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Return to CHIROPRACTIC CARE FOR VETERANS

Since 6-12-2021

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |